Insulin Deficiency Exacerbates Muscle Atrophy and Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

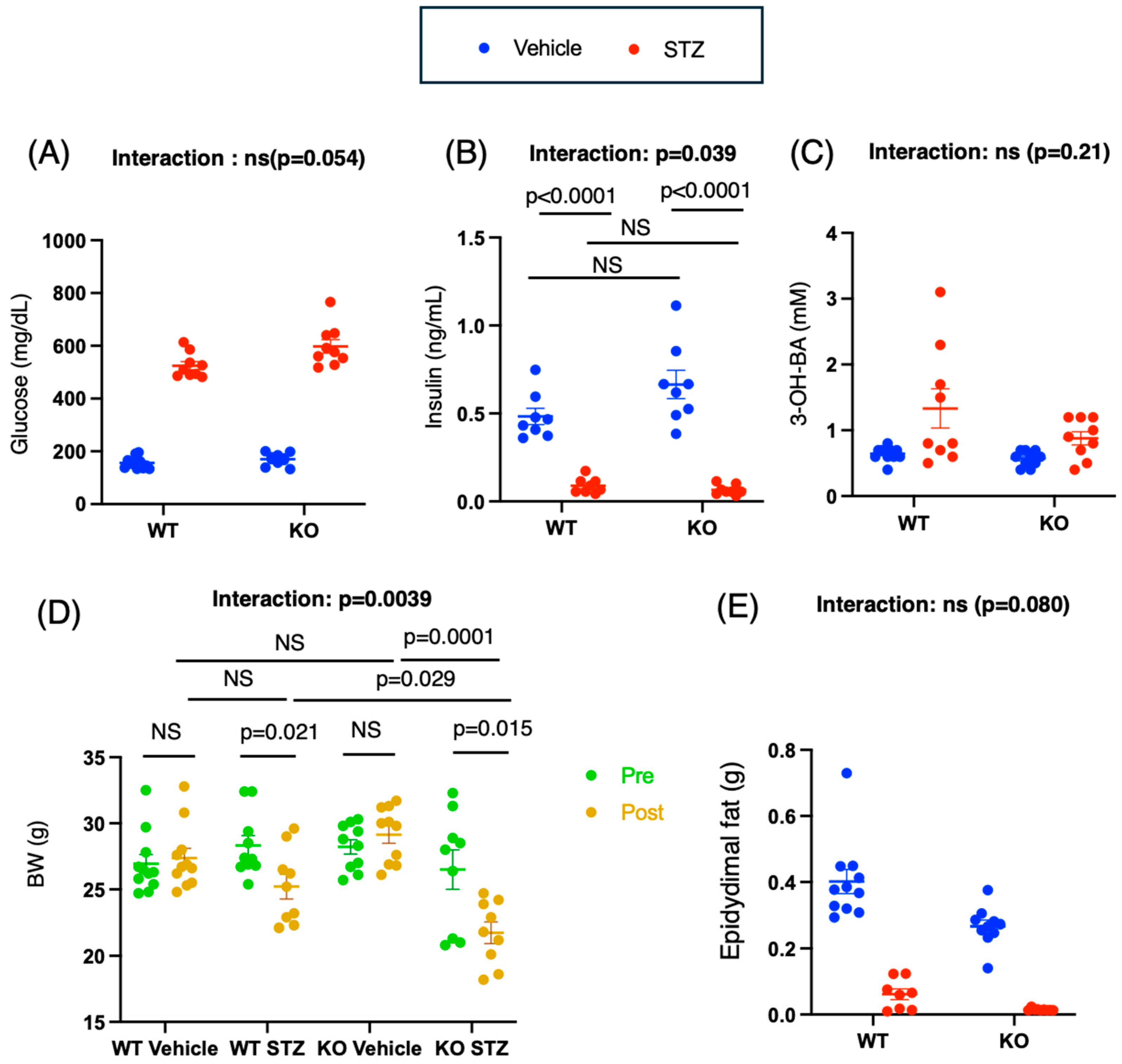

2.1. STZ Administration Induces Diabetes Mellitus in WT and KO Mice

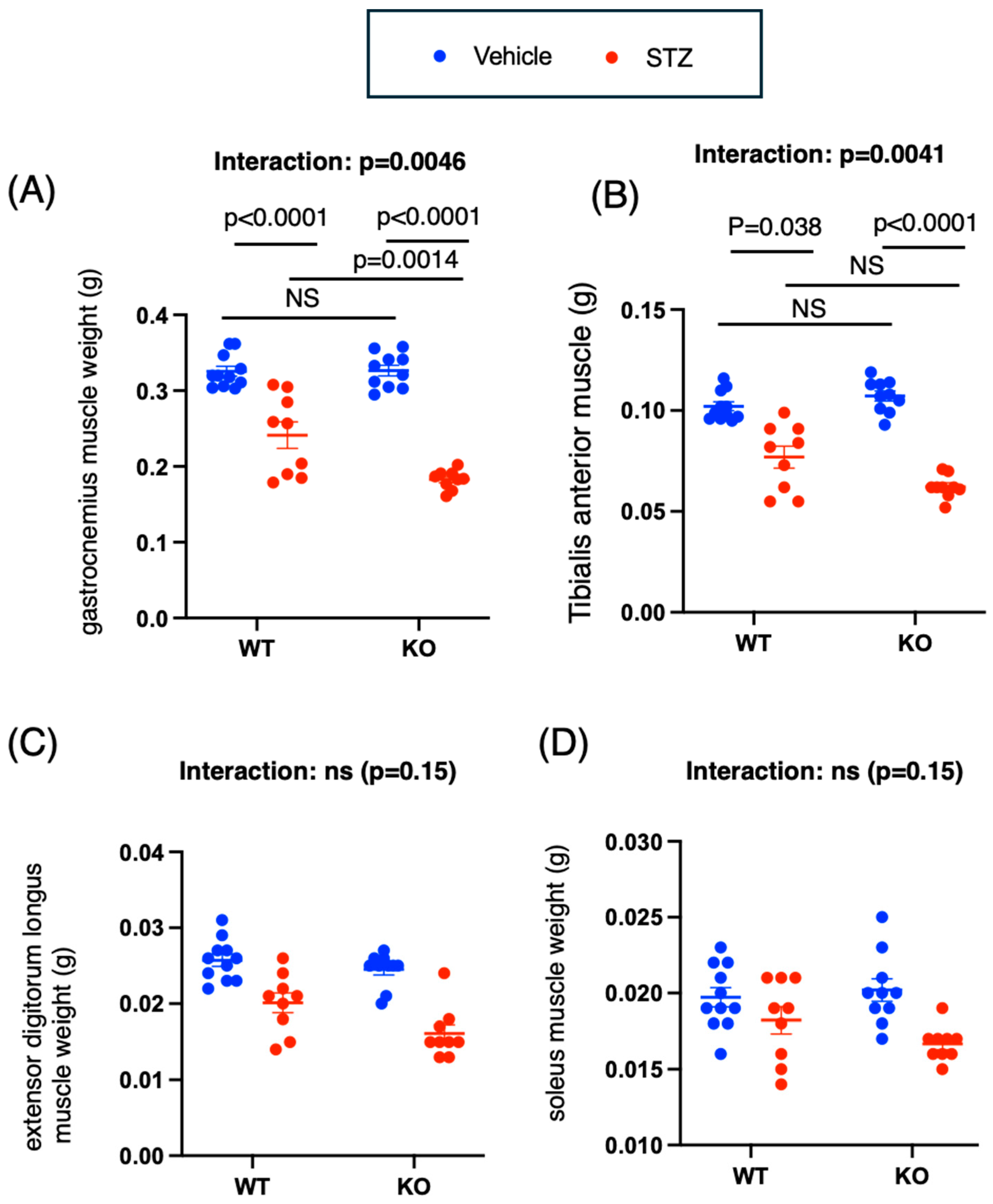

2.2. Chrebp Deletion Promotes Muscle Atrophy and Decreases Grip Strength in STZ-Treated Mice

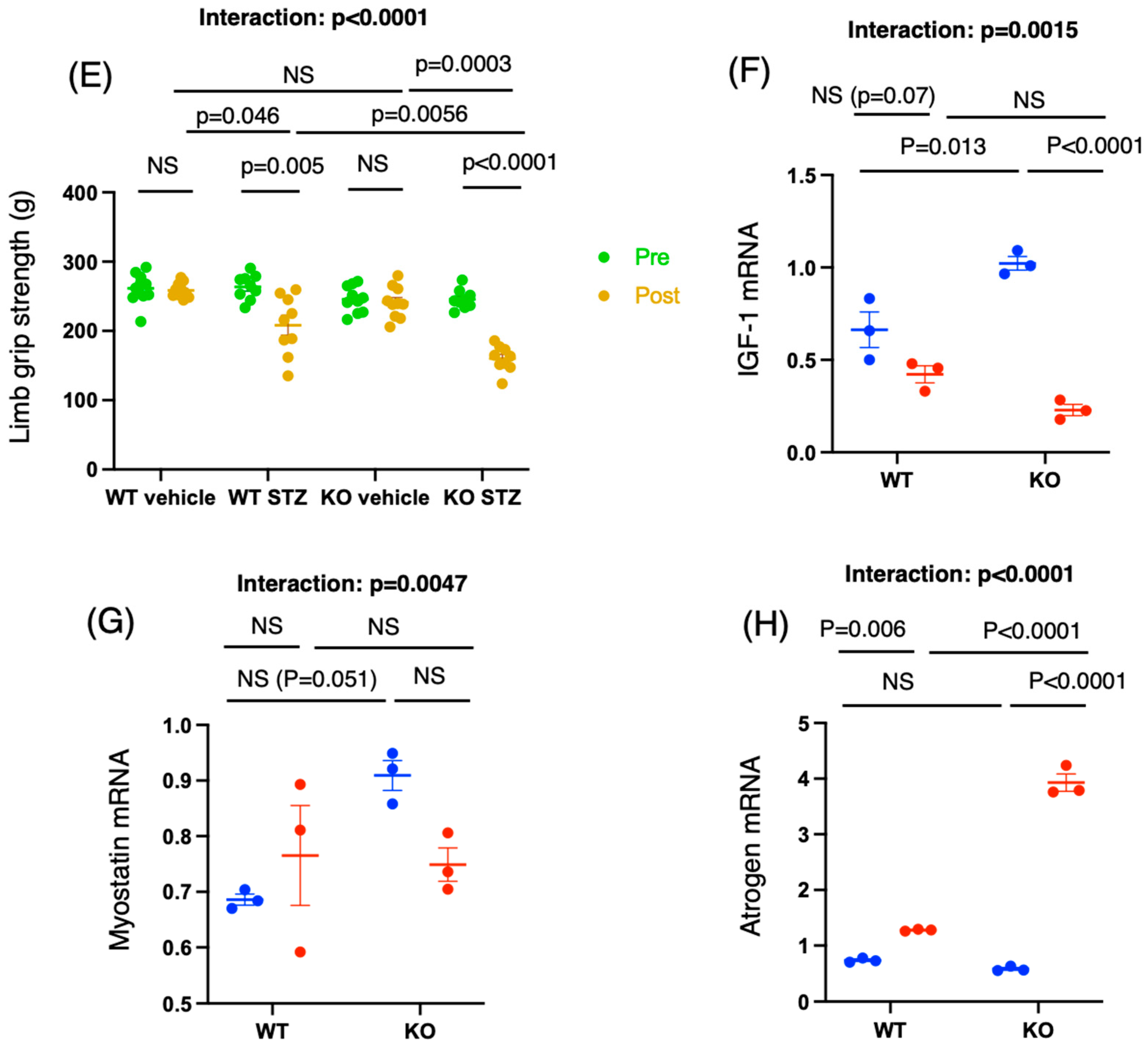

2.3. Insulin Deficiency Promotes Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice

2.3.1. Bone Mineral Density and Stiffness

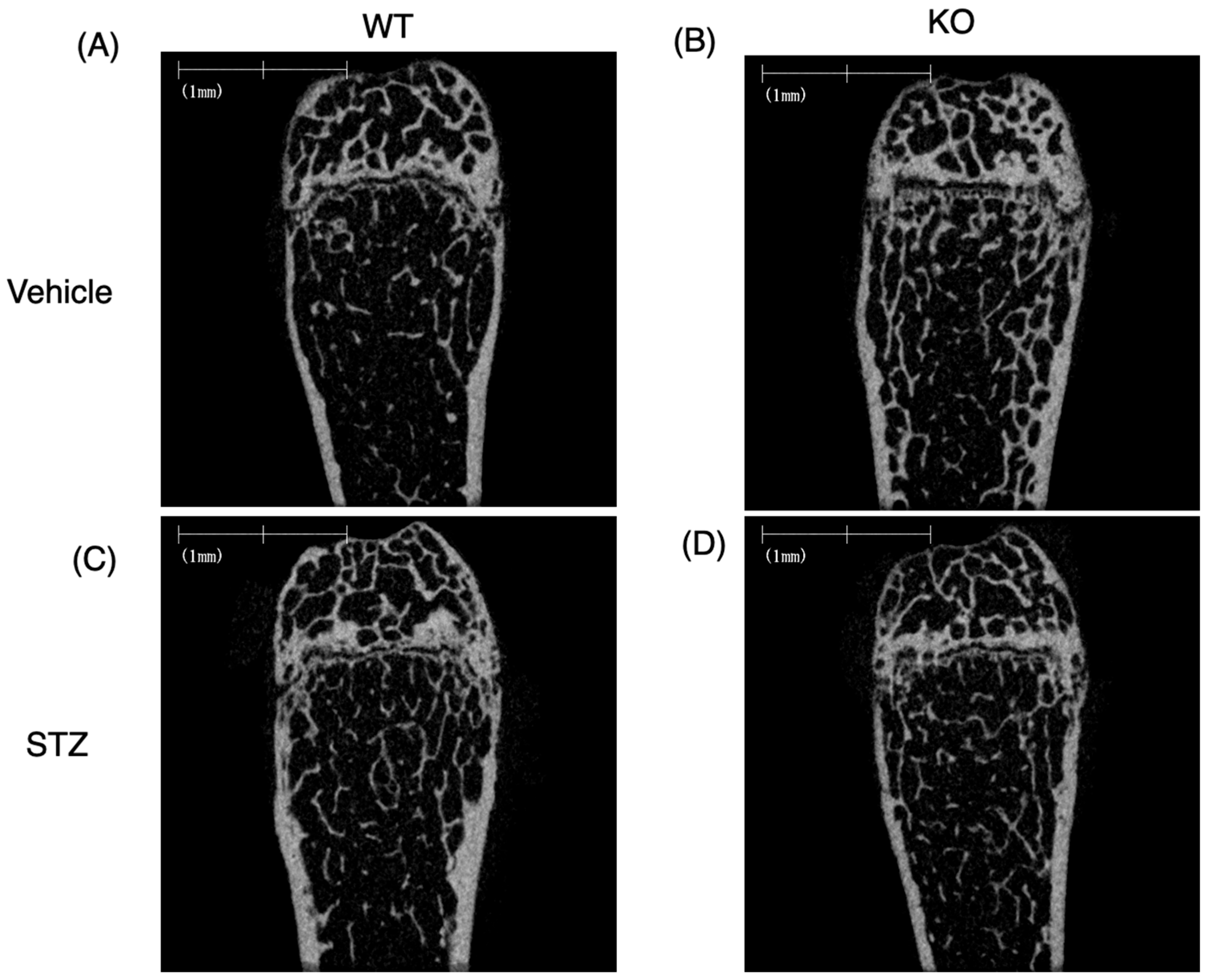

2.3.2. Bone Structure Analysis by μCT

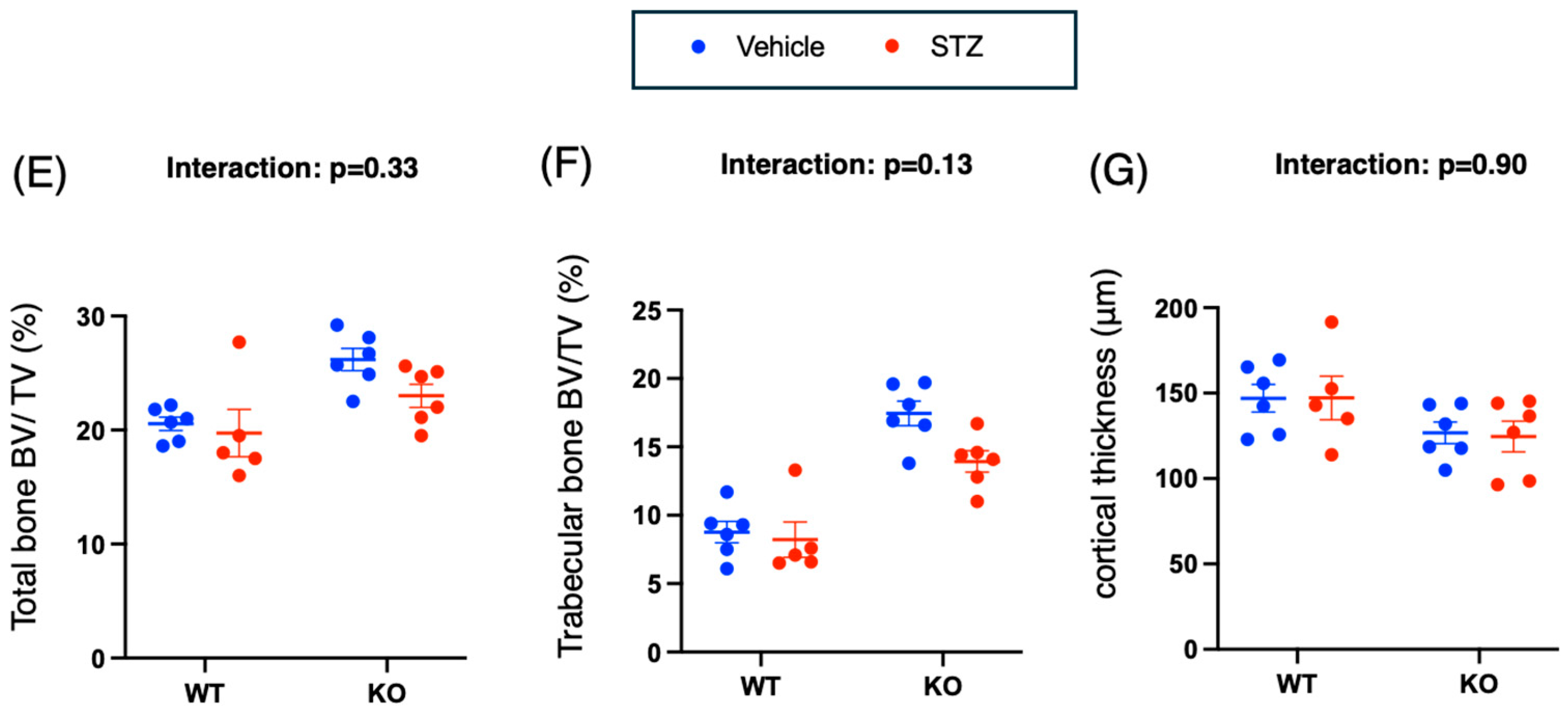

2.3.3. Bone Structure Analysis of Microscopic Specimens

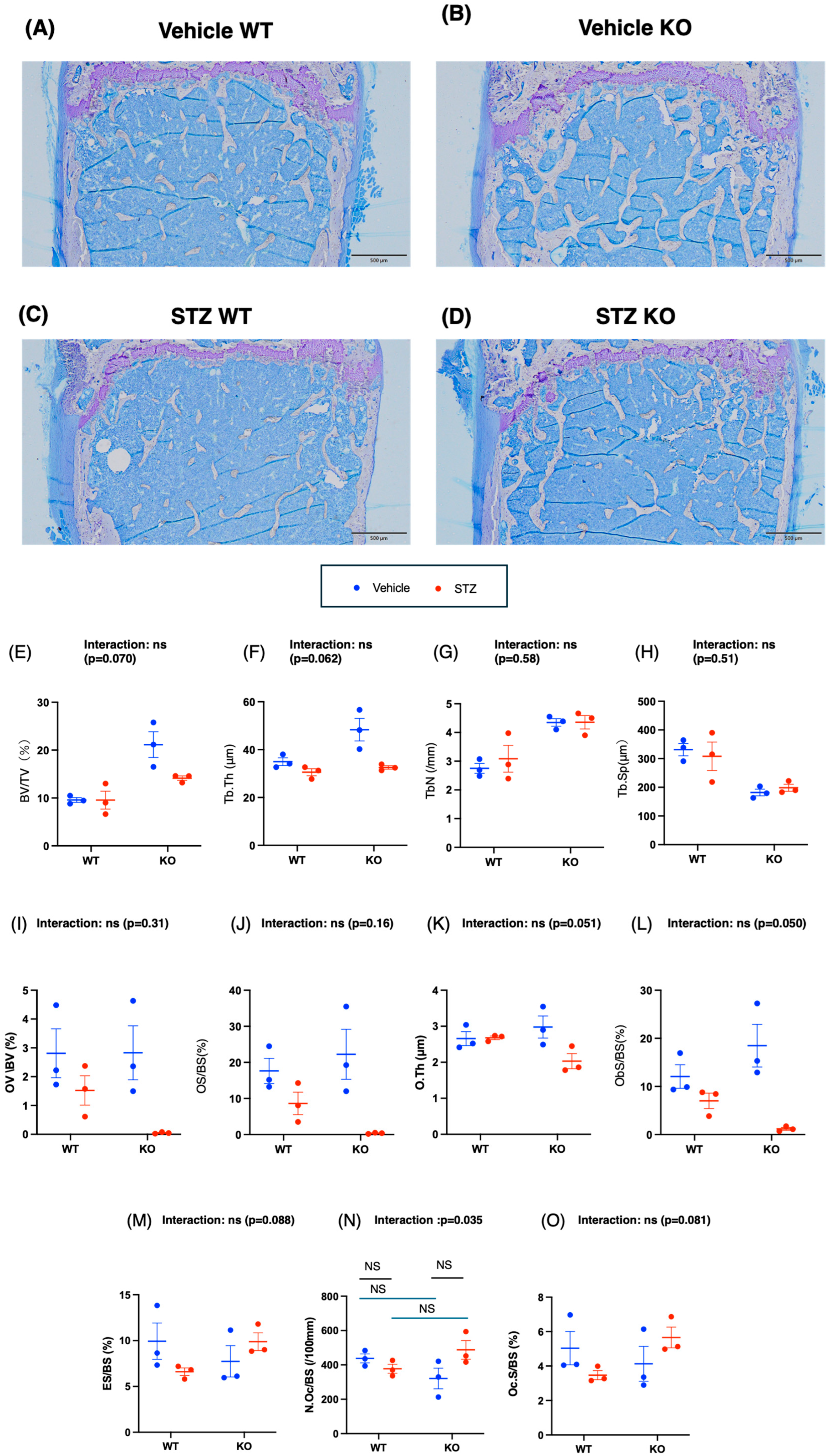

2.3.4. mRNA Analysis of Bone

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Animals

- (1)

- >20% loss of body weight compared with baseline;

- (2)

- A marked reduction in food or water intake for more than 24–48 h;

- (3)

- Severe lethargy or inability to ambulate;

- (4)

- persistent signs of distress, such as piloerection, dehydration, or respiratory difficulty;

- (5)

- Experimental-specific complications that could not be alleviated.

4.3. Streptozocin Administration

4.4. Body and Tissue Weight Measurements

4.5. Measurement of Blood Glucose, Insulin, and 3-Hydroxybutyrate Concentrations

4.6. Muscle Weight and Limb Grip Strength Measurement

4.7. Bone Mineral Density Measurement

4.8. Three-Point Bending Tests

4.9. Microcomputed Tomography Analysis

4.10. Bone Histomorphometric Analysis

4.11. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Reverse Transcription–PCR

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buschard, K. The Etiology and Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes—A Personal, Non-Systematic Review of Possible Causes, and Interventions. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 876470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T.; Dadheech, N.; Tan, E.H.P.; Ng, N.H.J.; Koh, M.B.C.; Shapiro, J.; Teo, A.K.K. Stem Cell Therapies for Diabetes. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, B.J.; Rickels, M.R.; Bellin, M.D.; Millman, J.R.; Tomei, A.A.; García, A.J.; Shirwan, H.; Stabler, C.L.; Ma, M.; Yi, P.; et al. Advances in Cell Replacement Therapies for Diabetes. Diabetes 2025, 74, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, M.; Ling, P.; Lin, B.; Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, H.; Yang, D.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Tubeless Open-Source Hybrid Automated Insulin Delivery Use at Home Among Adults with T1DM Mellitus: Results from a 26-Week, Free-Living, Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4699–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughton, S.; Riley, D.; Berry, S.; Arshad, M.F.; Eleftheriadou, A.; Anson, M.; Yap, Y.W.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Malik, R.A.; Azmi, S.; et al. The Impact of Insulin Pump Therapy Compared to Multiple Daily Injections on Complications and Mortality in T1DM: A Real-World Retrospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4239–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzadeh, A.; Patel, M.; Connock, M.; Damery, S.; Ghosh, I.; Jordan, M.; Freeman, K.; Brown, A.; Court, R.; Baldwin, S.; et al. Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems for Managing Blood Glucose Levels in T1DM: A Systematic Review and Economic Modeling. Health Technol. Assess. 2024, 28, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Carnicero-Carreño, J.A.; Davies, B.; Garcia-Garcia, F.J.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Alonso-Bouzón, C. Role of Sarcopenia in the Frailty Transitions in Older Adults: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia and Frailty: New Challenges for Clinical Practice. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.C. Sarcopenia, Frailty, and Diabetes in Older Adults. Diabetes Metab. J. 2016, 40, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, A.; Jeddi, S. Streptozotocin as a Tool for Induction of Rat Models of Diabetes: A Practical Guide. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 274–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahdi, A.M.T.A.; John, A.; Raza, H. Elucidation of Molecular Mechanisms of Streptozotocin-Induced Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Rin-5F Pancreatic β-Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7054272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaccio, G.; Pisanti, F.A.; Latronico, M.V.; Ammendola, E.; Galdieri, M. Multiple Low-Dose and Single High-Dose Treatments with Streptozotocin Do Not Generate Nitric Oxide. J. Cell. Biochem. 2000, 77, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaon, P.; Shah, V.N. T1DM and Osteoporosis: A Review of Literature. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.S.; Fraser, L.A. T1DM and Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Bone Phenotype. J. Osteoporos. 2015, 2015, 174186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, P. Discrepancies in Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk in Patients with Type 1 and T2DM: A Meta-Analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2007, 18, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Varthakavi, P.; Chadha, M.; Bhagwat, N. A Study of Bone Mineral Density and Its Determinants in T1DM. J. Osteoporos. 2013, 2013, 397814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromine, Y.; Noso, S.; Rakugi, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Takata, Y.; Katsuya, T.; Fukuda, M.; Akasaka, H.; Osawa, H.; Tabara, Y.; et al. Poor Glycemic Control Rather than Types of Diabetes Is a Risk Factor for Sarcopenia in Diabetes Mellitus: The MUSCLES-DM Study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2022, 13, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zou, S.; Luo, T.; Lai, J.; Ying, J.; Lin, M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Osteosarcopenia in Elderly Patients with Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrine 2025, 87, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, C.; Chen, F.; Xie, D.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, F. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Osteosarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Shen, X.; Li, G.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; Sheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Song, Q.; et al. New Evidence, Creative Insights, and Strategic Solutions: Advancing the Understanding and Practice of Diabetes Osteoporosis. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Deya Edelen, E.; Zhuo, W.; Khan, A.; Orbegoso, J.; Greenfield, L.; Rahi, B.; Griffin, M.; Ilich, J.Z.; Kelly, O.J. Understanding the Consequences of Fatty Bone and Fatty Muscle: How the Osteosarcopenic Adiposity Phenotype Uncovers the Deterioration of Body Composition. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Shi, H.; Cai, M.; Li, Y.; Zhao, R.; Qin, D. Muscle-Bone Biochemical Crosstalk in Osteosarcopenia: Focusing on Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 266, e250234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguchi, K.; Ushiroda, C.; Hidaka, S.; Tsuchida, H.; Yamamoto-Wada, R.; Seino, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Yabe, D.; Iizuka, K. Chrebp Deletion and Mild Protein Restriction Additively Decrease Muscle and Bone Mass and Function. Nutrients 2025, 17, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, K.; Ushiroda, C.; Kamei, Y.; Kondo, K.; Tsuchida, H.; Seino, Y.; Yabe, D.; Suzuki, A.; Nagao, S.; Iizuka, K. Glucose and Insulin Differently Regulate Gluconeogenic and Ureagenic Gene Expression. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2025, 71, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, A.G.; Li, S.; Choi, H.Y.; Fang, F.; Fukasawa, M.; Uyeda, K.; Hammer, R.E.; Horton, J.D.; Engelking, L.J.; Liang, G. Interplay between ChREBP and SREBP-1c Coordinates Postprandial Glycolysis and Lipogenesis in Livers of Mice. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeda, K. Short- and Long-Term Adaptation to Altered Levels of Glucose: Fifty Years of Scientific Adventure. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K. The Roles of Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein in the Relationship between Carbohydrate Intake and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbinatti, T.; Régnier, M.; Parlati, L.; Benhamed, F.; Postic, C. New Insights into the Interorgan Crosstalk Mediated by ChREBP. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1095440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, K.; Iizuka, K.; Liu, Y.; Sakurai, T.; Kubota, S.; Kubota-Okamoto, S.; Imaizumi, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Rakhat, Y.; Komori, S.; et al. Effects of ChREBP Deficiency on Adrenal Lipogenesis and Steroidogenesis. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 248, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.; Aryal, P.; Wen, J.; Syed, I.; Vazirani, R.P.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Camporez, J.P.; Gallop, M.R.; Perry, R.J.; Peroni, O.D.; et al. Absence of Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein in Adipocytes Causes Systemic Insulin Resistance and Impairs Glucose Transport. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wollheim, C.B. ChREBP Rather than USF2 Regulates Glucose Stimulation of Endogenous L-Pyruvate Kinase Expression in Insulin-Secreting Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 32746–32752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Astapova, I.I.; Flier, S.N.; Hannou, S.A.; Doridot, L.; Sargsyan, A.; Kou, H.H.; Fowler, A.J.; Liang, G.; Herman, M.A. Intestinal, but Not Hepatic, ChREBP Is Required for Fructose Tolerance. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e96703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Iizuka, K.; Takao, K.; Horikawa, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Takeda, J. ChREBP-Knockout Mice Show Sucrose Intolerance and Fructose Malabsorption. Nutrients 2018, 10, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K.; Wu, W.; Horikawa, Y.; Saito, M.; Takeda, J. Feedback Looping between ChREBP and PPARα in the Regulation of Lipid Metabolism in Brown Adipose Tissues. Endocr. J. 2013, 60, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, E.J.; Jang, W.G. Carbohydrate Responsive Element Binding Protein (ChREBP) Negatively Regulates Osteoblast Differentiation via Protein Phosphatase 2A C Dependent Manner. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 124, 105766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recazens, E.; Tavernier, G.; Dufau, J.; Bergoglio, C.; Benhamed, F.; Cassant-Sourdy, S.; Marques, M.A.; Caspar-Bauguil, S.; Brion, A.; Monbrun, L.; et al. ChREBPβ Is Dispensable for the Control of Glucose Homeostasis and Energy Balance. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e153431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milluzzo, A.; Quaranta, G.; Manuella, L.; Sceusa, G.; Bosco, G.; Giacomo Barbagallo, F.D.; Di Marco, M.; Lombardo, A.M.; Oteri, V.; Sciacca, L.; et al. Sarcopenia in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 227, 112399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.; Wan, S.; Jaiswal, N.; Vega, R.B.; Ayer, D.E.; Titchenell, P.M.; Han, X.; Won, K.J.; Kelly, D.P. MondoA Drives Muscle Lipid Accumulation and Insulin Resistance. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e129119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.; Soundarapandian, M.M.; Sessions, H.; Peddibhotla, S.; Roth, G.P.; Li, J.L.; Sugarman, E.; Koo, A.; Malany, S.; Wang, M.; et al. MondoA Coordinately Regulates Skeletal Myocyte Lipid Homeostasis and Insulin Signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3567–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, M.; Chang, B.H.; Kohjima, M.; Li, M.; Hwang, B.; Taegtmeyer, H.; Harris, R.A.; Chan, L. MondoA Deficiency Enhances Sprint Performance in Mice. Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazy, V.; Sore, S.; Viaud, M.; Rignol, G.; Westerterp, M.; Ceppo, F.; Tanti, J.F.; Guinamard, R.; Gautier, E.L.; Yvan-Charvet, L. Maintenance of Macrophage Redox Status by ChREBP Limits Inflammation and Apoptosis and Protects against Advanced Atherosclerotic Lesion Formation. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Insulin Stimulates Osteoblast Proliferation and Differentiation Through ERK and PI3K in MG-63 Cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2010, 28, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, N.; Conte, C. Bone Fragility in Type 1 Diabetes: New Insights and Future Steps. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, M.; Iizuka, K.; Kato, T.; Liu, Y.; Takao, K.; Nonomura, K.; Mizuno, M.; Yabe, D. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor and Sarcopenia in a Lean Elderly Adult with Type 2 Diabetes: A Case Report. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; Okada, H.; Takegami, M.; Nakajima, H.; Miyoshi, T.; Yoshimura, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Hamaguchi, M.; Fukui, M. Changes in Glycemic Control and Skeletal Muscle Mass Indices After Dapagliflozin Treatment in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023, 14, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.V.; Backlund, J.C.; de Boer, I.H.; Rubin, M.R.; Barnie, A.; Farrell, K.; Trapani, V.R.; Gregory, N.S.; Wallia, A.; Bebu, I.; et al. Risk Factors for Lower Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilka, R.L. The Relevance of Mouse Models for Investigating Age-Related Bone Loss in Humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.; Kondamudi, N.P. Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482142/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Lorenzo, I.; Serra-Prat, M.; Yébenes, J.C. The Role of Water Homeostasis in Muscle Function and Frailty: A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Prat, M.; Lorenzo, I.; Palomera, E.; Ramírez, S.; Yébenes, J.C. Total Body Water and Intracellular Water Relationships with Muscle Strength, Frailty and Functional Performance in an Elderly Population. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, J.S.; Roy, A.; Shen, X.; Acuna, R.L.; Tyler, J.H.; Wang, X. The Influence of Water Removal on the Strength and Toughness of Cortical Bone. J. Biomech. 2006, 39, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, S. The Mechanisms of Alloxan- and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Human Protein Atlas. MLXIPL. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000009950-MLXIPL (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Ferron, M.; Wei, J.; Yoshizawa, T.; Del Fattore, A.; DePinho, R.A.; Teti, A.; Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. Insulin Signaling in Osteoblasts Integrates Bone Remodeling and Energy Metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Guntur, A.R.; Long, F.; Rosen, C.J. Energy Metabolism of the Osteoblast: Implications for Osteoporosis. Endocr. Rev. 2017, 38, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, P.; Wolfgang, M.J.; Riddle, R.C. Fatty Acid Metabolism by the Osteoblast. Bone 2018, 115, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Min, K.H. Metabolic Reprogramming in Osteoclasts. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Ji, K.; Chen, Z.; He, G.; et al. Pharmacologically Targeting Fatty Acid Synthase-Mediated de Novo Lipogenesis Alleviates Osteolytic Bone Loss by Directly Inhibiting Osteoclastogenesis Through Suppression of STAT3 Palmitoylation and ROS Signaling. Metabolism 2025, 167, 156186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, N.; Yoshimatsu, G.; Tsuchiya, H.; Egawa, S.; Unno, M. Animal Models of Diabetes Mellitus for Islet Transplantation. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 2012, 256707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard, S.A.; Søndergaard, H.; Sørensen, D.B.; Galsgaard, E.D.; Hess, C.; Sand, F.W. Optimizing Streptozotocin Dosing to Minimize Renal Toxicity and Impairment of Stomach Emptying in Male 129/Sv Mice. Lab. Anim. 2020, 54, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ushiroda, C.; Ito, M.; Yamamoto-Wada, R.; Deguchi, K.; Hidaka, S.; Imaizumi, T.; Seino, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Yabe, D.; Iizuka, K. Insulin Deficiency Exacerbates Muscle Atrophy and Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311672

Ushiroda C, Ito M, Yamamoto-Wada R, Deguchi K, Hidaka S, Imaizumi T, Seino Y, Suzuki A, Yabe D, Iizuka K. Insulin Deficiency Exacerbates Muscle Atrophy and Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311672

Chicago/Turabian StyleUshiroda, Chihiro, Mioko Ito, Risako Yamamoto-Wada, Kanako Deguchi, Shihomi Hidaka, Toshinori Imaizumi, Yusuke Seino, Atsushi Suzuki, Daisuke Yabe, and Katsumi Iizuka. 2025. "Insulin Deficiency Exacerbates Muscle Atrophy and Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311672

APA StyleUshiroda, C., Ito, M., Yamamoto-Wada, R., Deguchi, K., Hidaka, S., Imaizumi, T., Seino, Y., Suzuki, A., Yabe, D., & Iizuka, K. (2025). Insulin Deficiency Exacerbates Muscle Atrophy and Osteopenia in Chrebp Knockout Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311672