Respiratory Delivery of Highly Conserved Antiviral siRNAs Suppress SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Conservation Analysis of Lead Candidate Anti-COVID siRNAs in SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 Human and Animal Sequences

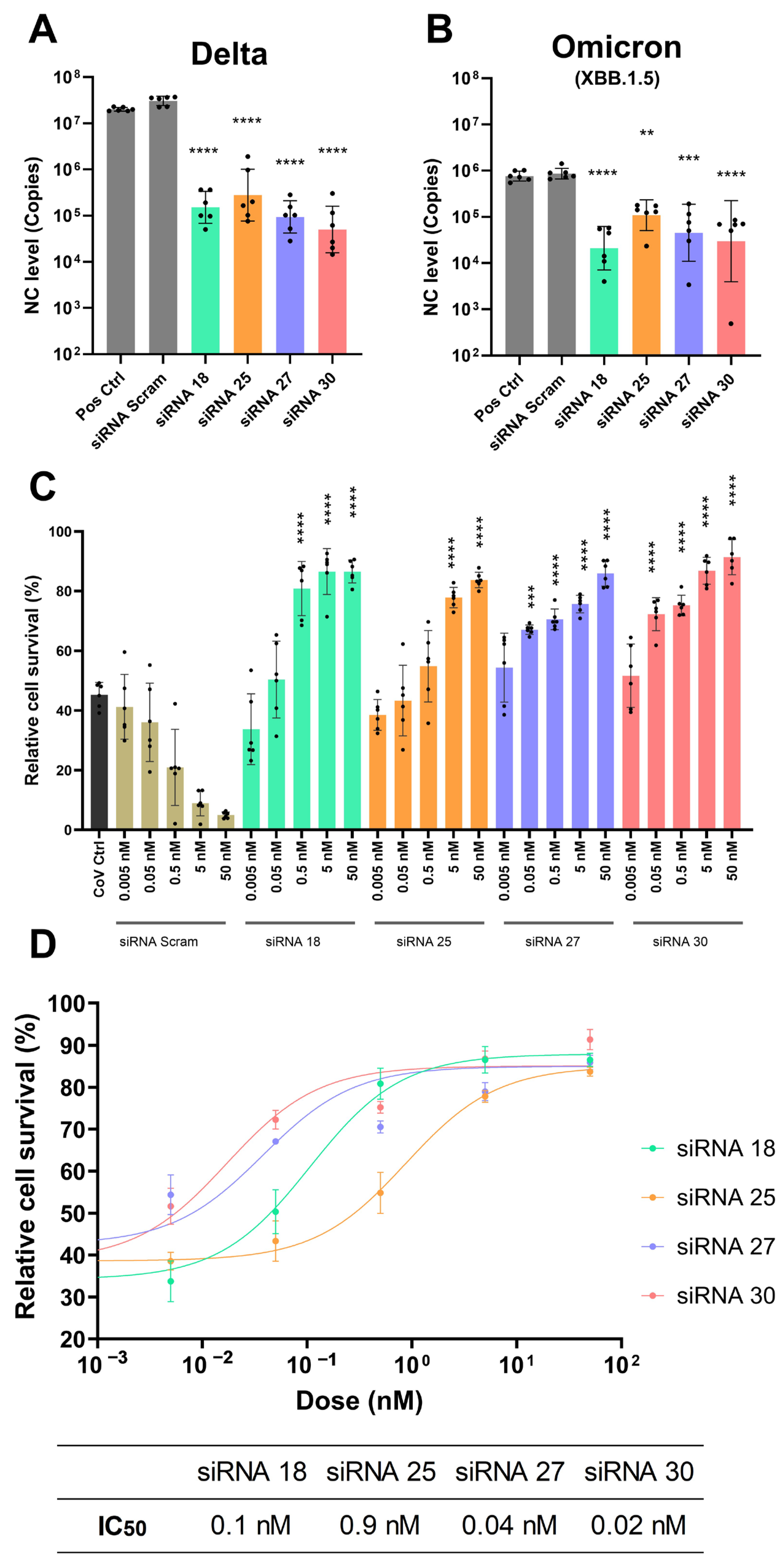

2.2. Gene Silencing Effect of Lead Candidate Anti-COVID siRNAs and Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection

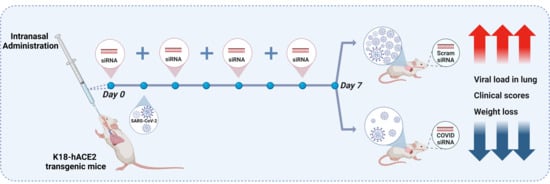

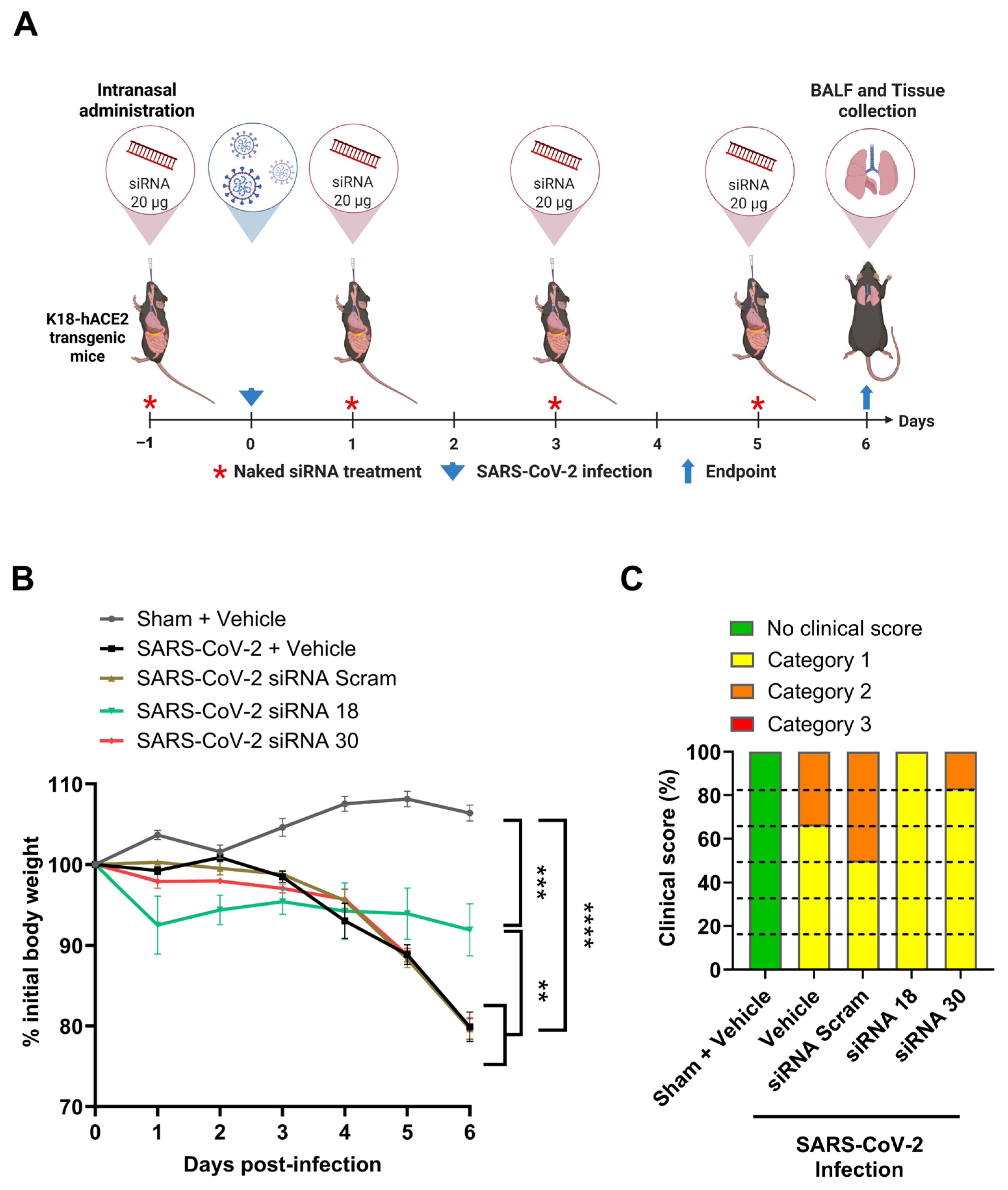

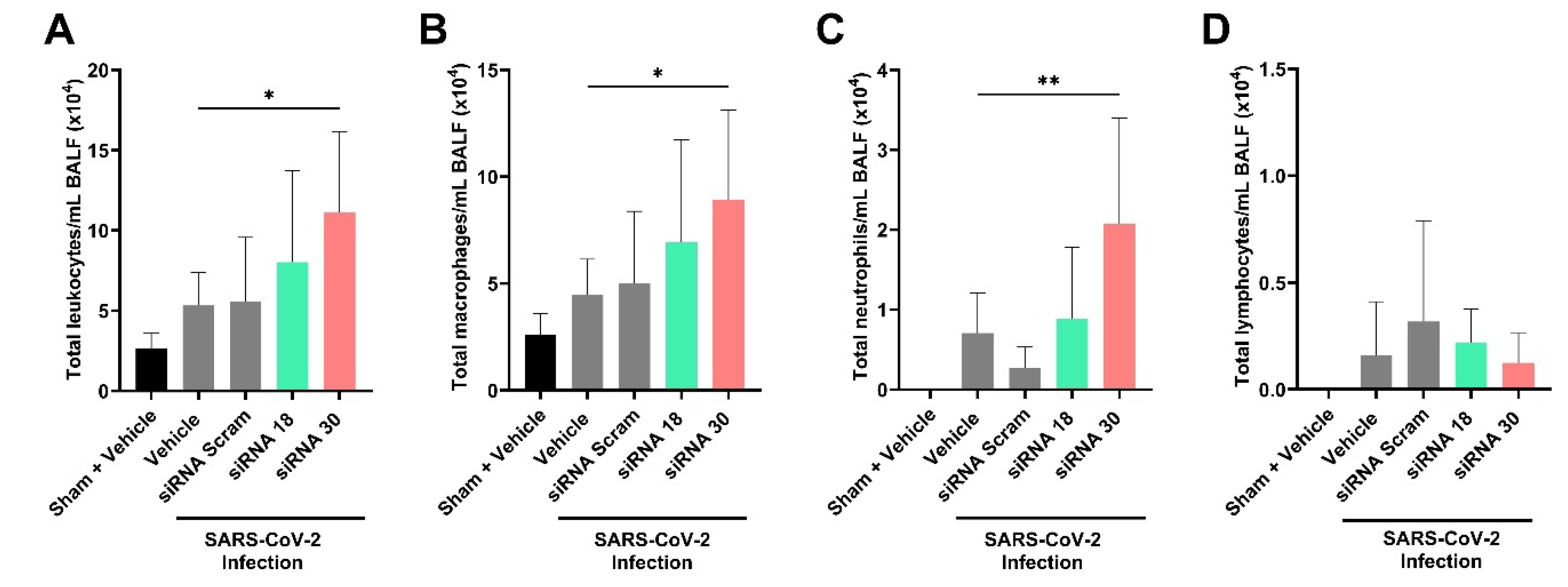

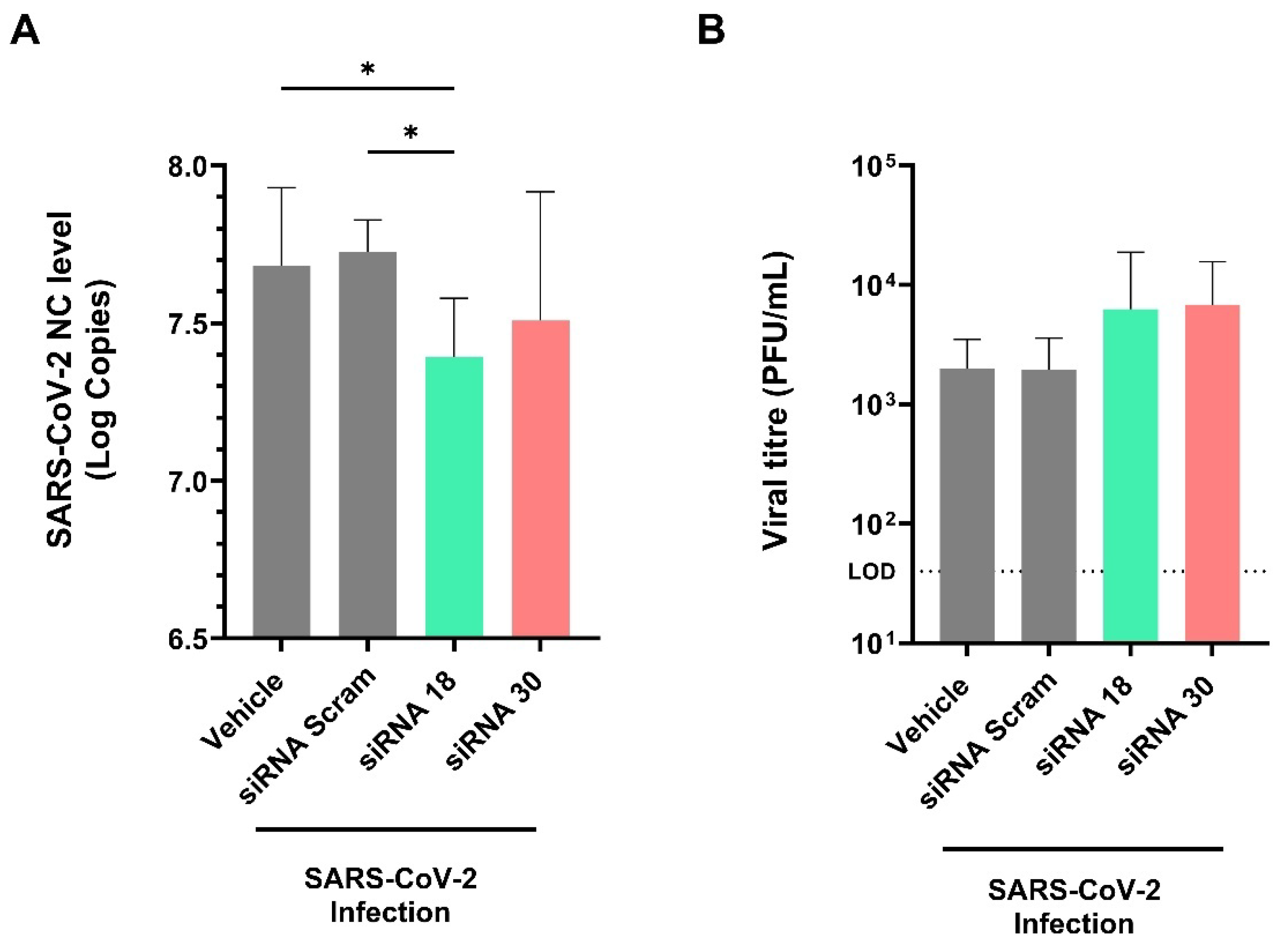

2.3. The Protective Effect of siRNAs Against SARS-CoV-2 In Vivo

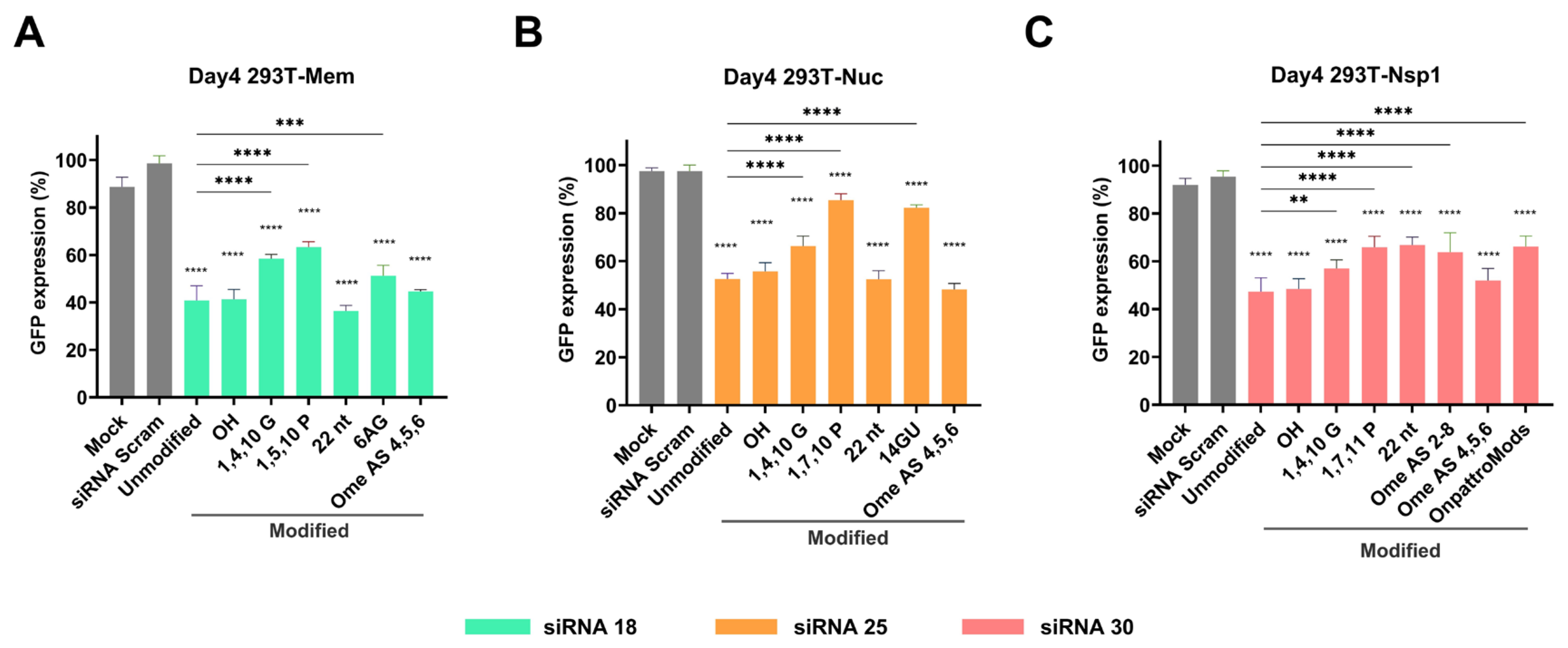

2.4. Gene Silencing Effect of Chemically Modified siRNAs

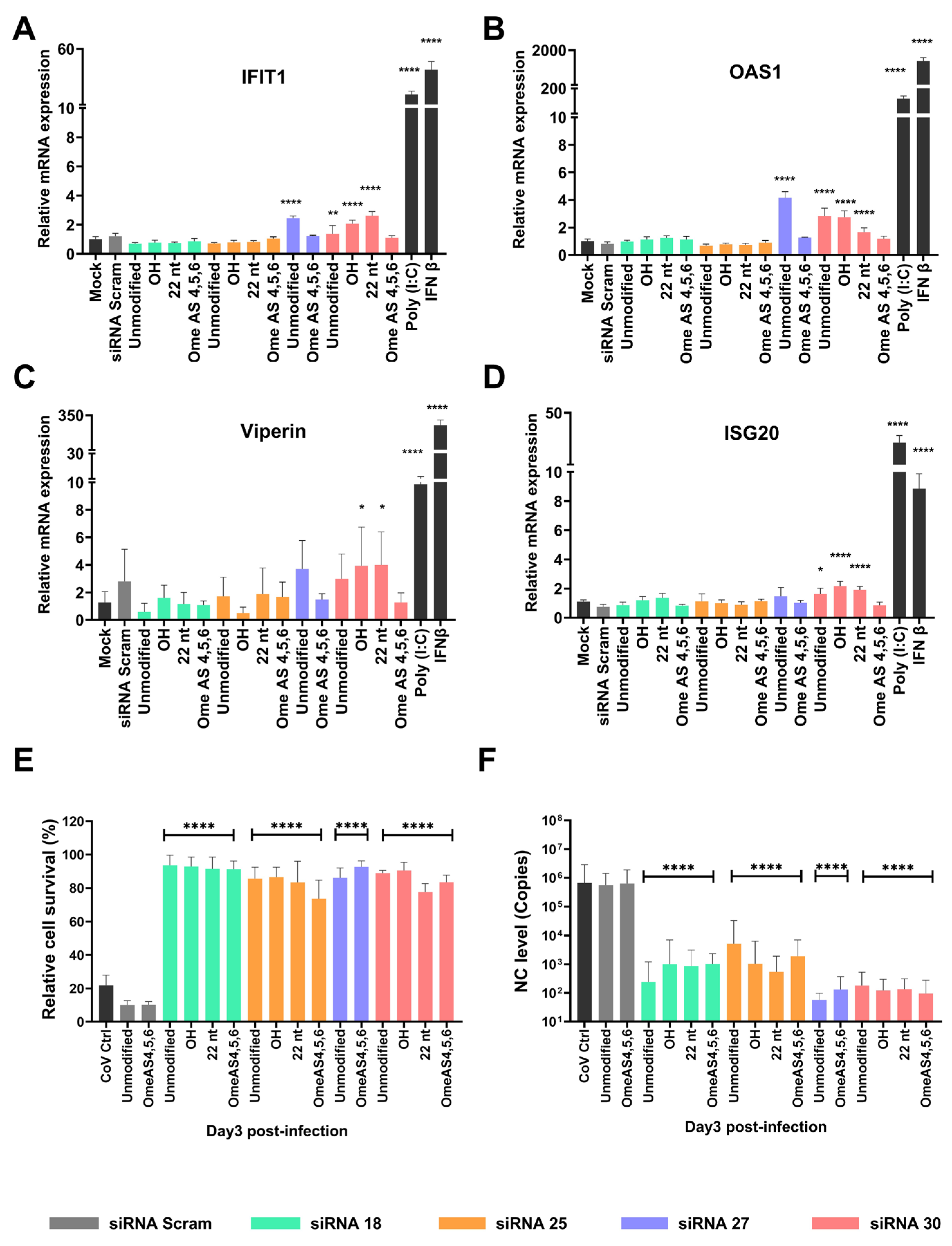

2.5. Chemical Modifications Reduce ISG Activation While Preserving Antiviral Efficacy of siRNAs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Viruses

4.4. Conservation Analysis

4.5. Construction and Verification of SARS-CoV-2 Lentiviral-GFP Reporter Cell Lines

4.6. siRNA Transfection Using Lipofectamine

4.7. Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

4.8. Protective Effect of siRNAs Against SARS-CoV-2

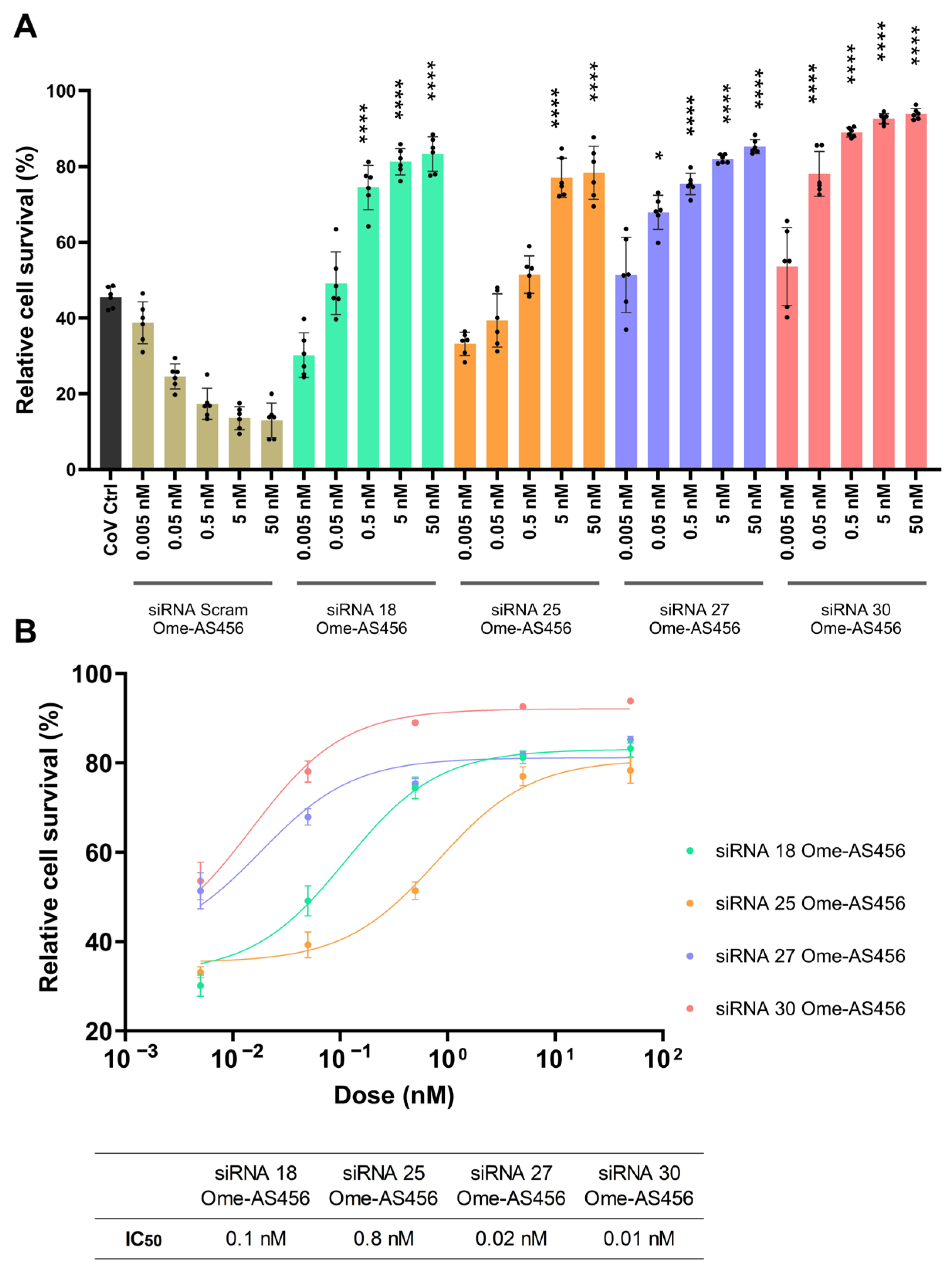

4.9. Dose-Response Assay for siRNAs and LNP-siRNAs

4.10. Cell Survival Assay

4.11. In Vivo Assessment of siRNA Treatment in a SARS-CoV-2 Mouse Model of Infection

4.12. Off-Target Effect of siRNAs

4.13. siRNA Modifications

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| ISG | Interferon-stimulated gene |

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, R. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Response to COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients With Primary Immunodeficiencies. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228 (Suppl. S1), S24–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, C.; Ursini, F.; Gragnani, L.; Raimondo, V.; Giuggioli, D.; Foti, R.; Caminiti, M.; Olivo, D.; Cuomo, G.; Visentini, M.; et al. Impaired immunogenicity to COVID-19 vaccines in autoimmune systemic diseases. High prevalence of non-response in different patients’ subgroups. J. Autoimmun. 2021, 125, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.; Powell, M.; Yang, E.; Kar, A.; Leung, T.M.; Sison, C.; Steinberg, R.; Mims, R.; Choudhury, A.; Espinosa, C.; et al. Factors associated with immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in individuals with autoimmune diseases. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e180750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J.; Bell, M.R.; Marcy, J.; Kutzler, M.; Haddad, E.K. The impact of immuno-aging on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Geroscience 2021, 43, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.; Joean, O.; Welte, T.; Rademacher, J. The role of vaccination in COPD: Influenza, SARS-CoV-2, pneumococcus, pertussis, RSV and varicella zoster virus. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Ardanuy, J.; Hammond, H.; Logue, J.; Jackson, L.; Baracco, L.; McGrath, M.; Dillen, C.; Patel, N.; Smith, G.; et al. Diet-induced obesity and diabetes enhance mortality and reduce vaccine efficacy for SARS-CoV-2. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0133623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, B.; Grimm, D.; Kruger, M.; Kopp, S.; Infanger, M.; Wehland, M. SARS-CoV-2 and hypertension. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Balena, A.; Tuccinardi, D.; Tozzi, R.; Risi, R.; Masi, D.; Caputi, A.; Rossetti, R.; Spoltore, M.E.; Filippi, V.; et al. Central obesity, smoking habit, and hypertension are associated with lower antibody titres in response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Diabetes. Metab. Res. Rev. 2022, 38, e3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Berenbaum, F.; Curigliano, G.; Pliakas, T.; Sheikh, A.; Abduljawad, S. Risk of Severe Outcomes From COVID-19 in Immunocompromised People During the Omicron Era: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 770–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytyci, J.; Ying, Y.; Lee, L.Y.W. Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk of COVID-19 breakthrough infection, hospitalization, and death in the post-vaccination era: A systematic review. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatovkanukova, P.; Vesely, D.; Sliva, J. Evaluating Drug Interaction Risks: Nirmatrelvir & Ritonavir Combination (PAXLOVID((R))) with Concomitant Medications in Real-World Clinical Settings. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Almazi, J.G.; Ong, H.X.; Johansen, M.D.; Ledger, S.; Traini, D.; Hansbro, P.M.; Kelleher, A.D.; Ahlenstiel, C.L. Nanoparticle Delivery Platforms for RNAi Therapeutics Targeting COVID-19 Disease in the Respiratory Tract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ga, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, C.; Yeh, J.Y. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutic applications against viruses: Principles, potential, and challenges. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden-Reid, E.; Moles, E.; Kelleher, A.; Ahlenstiel, C. Harnessing antiviral RNAi therapeutics for pandemic viruses: SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. Drug. Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 2301–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden-Reid, E.; Ledger, S.; Zhang, Y.; Di Giallonardo, F.; Aggarwal, A.; Stella, A.O.; Akerman, A.; Milogiannakis, V.; Walker, G.; Rawlinson, W.; et al. Novel siRNA therapeutics demonstrate multi-variant efficacy against SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral. Res. 2023, 217, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Yang, C.F.; Chen, Y.F.; Yang, C.C.; Chou, Y.L.; Chou, H.W.; Chang, T.Y.; Chao, T.L.; Hsu, S.C.; Ieong, S.M.; et al. A siRNA targets and inhibits a broad range of SARS-CoV-2 infections including Delta variant. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e15298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitko, V.; Musiyenko, A.; Shulyayeva, O.; Barik, S. Inhibition of respiratory viruses by nasally administered siRNA. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strapps, W.R.; Pickering, V.; Muiru, G.T.; Rice, J.; Orsborn, S.; Polisky, B.A.; Sachs, A.; Bartz, S.R. The siRNA sequence and guide strand overhangs are determinants of in vivo duration of silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 4788–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ma, H.; Ye, C.; Ramirez, D.; Chen, S.; Montoya, J.; Shankar, P.; Wang, X.A.; Manjunath, N. Improved siRNA/shRNA functionality by mismatched duplex. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhong, C.; Smith, N.A.; de Feyter, R.; Greaves, I.K.; Swain, S.M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.B. Nucleotide mismatches prevent intrinsic self-silencing of hpRNA transgenes to enhance RNAi stability in plants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Lu, M. RNA Interference-Induced Innate Immunity, Off-Target Effect, or Immune Adjuvant? Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, M.; Judge, A.; Liang, L.; McClintock, K.; Yaworski, E.; MacLachlan, I. 2′-O-methyl-modified RNAs act as TLR7 antagonists. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova Kruglova, N.S.; Meschaninova, M.I.; Venyaminova, A.G.; Zenkova, M.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Chernolovskaya, E.L. 2′-O-methyl-modified anti-MDR1 fork-siRNA duplexes exhibiting high nuclease resistance and prolonged silencing activity. Oligonucleotides 2010, 20, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iribe, H.; Miyamoto, K.; Takahashi, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Leo, J.; Aida, M.; Ui-Tei, K. Chemical Modification of the siRNA Seed Region Suppresses Off-Target Effects by Steric Hindrance to Base-Pairing with Targets. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Gonzalez-Duarte, A.; O’Riordan, W.D.; Yang, C.C.; Ueda, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Tournev, I.; Schmidt, H.H.; Coelho, T.; Berk, J.L.; et al. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Remdesivir: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, E.D. Casirivimab/Imdevimab: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Regdanvimab: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 2133–2137, Correction in Drugs 2021, 81, 2139.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Molnupiravir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Tixagevimab + Cilgavimab: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, S.M. Amubarvimab/Romlusevimab: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 585–591, Correction in Drugs 2022, 82, 1025.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.A. Sotrovimab: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, M.; Yu, K. Comparison of the therapeutic effect of Paxlovid and Azvudine in the treatment of COVID-19: A retrospective study. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedalipour, F.; Alipour, S.; Mehdinezhad, H.; Akrami, R.; Shirafkan, H. Incidence of Elevated Liver Enzyme Levels in Patients Receiving Remdesivir and Its Effective Factors. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 2024, 16, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinda, T.; Mizuno, S.; Tatami, S.; Kasai, M.; Ishida, T. Risk factors for liver enzyme elevation with remdesivir use in the treatment of paediatric COVID-19. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 60, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.M.; Wan, E.Y.F.; Ting Wong, Z.C.; Tam, A.R.; Kei Wong, I.C.; Yin Chan, E.W.; Ngai Hung, I.F. Comparison of safety and efficacy between Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and molnupiravir in the treatment of COVID-19 infection in patients with advanced kidney disease: A retrospective observational study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.J.; Jorgensen, C.K.; Faltermeier, P.; Siddiqui, F.; Feinberg, J.; Nielsen, E.E.; Torp Kristensen, A.; Juul, S.; Holgersson, J.; Nielsen, N.; et al. Drug interventions for prevention of COVID-19 progression to severe disease in outpatients: A systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses (The LIVING Project). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e064498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente-Lopez, A.; Hermosilla, J.; Navas, N.; Cuadros-Rodriguez, L.; Cabeza, J.; Salmeron-Garcia, A. The Relevance of Monoclonal Antibodies in the Treatment of COVID-19. Vaccines 2021, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yang, T.F.; Zheng, R. Theory and reality of antivirals against SARS-CoV-2. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 6663–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labeau, A.; Fery-Simonian, L.; Lefevre-Utile, A.; Pourcelot, M.; Bonnet-Madin, L.; Soumelis, V.; Lotteau, V.; Vidalain, P.O.; Amara, A.; Meertens, L. Characterization and functional interrogation of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA interactome. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y.P.; Bo, L.S.; Ke, W.B. miR-542-3p Appended Sorafenib/All-trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA)-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles to Enhance the Anticancer Efficacy in Gastric Cancers. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 2710–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngarande, E.; Doubell, E.; Tamgue, O.; Mano, M.; Human, P.; Giacca, M.; Davies, N.H. Modified fibrin hydrogel for sustained delivery of RNAi lipopolyplexes in skeletal muscle. Regen. Biomater. 2023, 10, rbac101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Ashiba, H.; Yasuura, M.; Fujimaki, M. Quick assessment of influenza a virus infectivity with a long-range reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Ogasawara, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Takano, K.; Shiraishi, T.; Sato, T.; Tsutsumi, H.; Himi, T.; Yokota, S.I. Evaluation of consistency in quantification of gene copy number by real-time reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction and virus titer by plaque-forming assay for human respiratory syncytial virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 62, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.G.; Nitsche, A.; Teichmann, A.; Biel, S.S.; Niedrig, M. Detection of yellow fever virus: A comparison of quantitative real-time PCR and plaque assay. J. Virol. Methods 2003, 110, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokwassanasakulkit, T.; Oti, V.B.; Idris, A.; McMillan, N.A. SiRNAs as antiviral drugs—Current status, therapeutic potential and challenges. Antiviral. Res. 2024, 232, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Lakdawala, S.; Quadir, S.S.; Puri, D.; Mishra, D.K.; Joshi, G.; Sharma, S.; Choudhary, D. siRNA-Based Novel Therapeutic Strategies to Improve Effectiveness of Antivirals: An Insight. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, T.P.; Allerson, C.R.; Dande, P.; Vickers, T.A.; Sioufi, N.; Jarres, R.; Baker, B.F.; Swayze, E.E.; Griffey, R.H.; Bhat, B. Positional effect of chemical modifications on short interference RNA activity in mammalian cells. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 4247–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Minakawa, N.; Matsuda, A. Synthesis and characterization of 2′-modified-4′-thioRNA: A comprehensive comparison of nuclease stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, A.S.; Sapkota, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, R.; Jayasekara, W.S.N.; Rupasinghe, E.; Speir, M.; Wilkinson-White, L.; Gamsjaeger, R.; Cubeddu, L.; et al. 2′-O-Methyl-guanosine 3-base RNA fragments mediate essential natural TLR7/8 antagonism. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.F.; Yang, C.F.; Ho, H.J.; Yang, J.F.; Chou, Y.L.; Lin, C.W.; Yang, P.C. Pharmacokinetics and Safety Profile of SNS812, a First in Human Fully Modified siRNA Targeting Wide-Spectrum SARS-CoV-2, in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025, 18, e70202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, V.N.; Shin, M.; Chang, C.W.; O’Reilly, D.; Biscans, A.; Yamada, K.; Guo, Z.; Somasundaran, M.; Tang, Q.; Monopoli, K.; et al. Divalent siRNAs are bioavailable in the lung and efficiently block SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219523120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Davis, A.; Supramaniam, A.; Acharya, D.; Kelly, G.; Tayyar, Y.; West, N.; Zhang, P.; McMillan, C.L.D.; Soemardy, C.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 targeted siRNA-nanoparticle therapy for COVID-19. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.L.; Burchard, J.; Leake, D.; Reynolds, A.; Schelter, J.; Guo, J.; Johnson, J.M.; Lim, L.; Karpilow, J.; Nichols, K.; et al. Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces “off-target” transcript silencing. RNA 2006, 12, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Larcher, L.M.; Ma, L.; Veedu, R.N. Systematic Screening of Commonly Used Commercial Transfection Reagents towards Efficient Transfection of Single-Stranded Oligonucleotides. Molecules 2018, 23, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betlej, G.; Bloniarz, D.; Lewinska, A.; Wnuk, M. Non-targeting siRNA-mediated responses are associated with apoptosis in chemotherapy-induced senescent skin cancer cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 369, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, T.R.; Johansen, M.D.; Balka, K.R.; Ambrose, R.L.; Gearing, L.J.; Roest, J.; Vivian, J.P.; Sapkota, S.; Jayasekara, W.S.N.; Wenholz, D.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of TBK1/IKKepsilon blunts immunopathology in a murine model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouet, R.; Henry, J.Y.; Johansen, M.D.; Sobti, M.; Balachandran, H.; Langley, D.B.; Walker, G.J.; Lenthall, H.; Jackson, J.; Ubiparipovic, S.; et al. Broadly neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies through epitope-based selection from convalescent patients. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counoupas, C.; Johansen, M.D.; Stella, A.O.; Nguyen, D.H.; Ferguson, A.L.; Aggarwal, A.; Bhattacharyya, N.D.; Grey, A.; Hutchings, O.; Patel, K.; et al. A single dose, BCG-adjuvanted COVID-19 vaccine provides sterilising immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlenstiel, C.; Mendez, C.; Lim, S.T.; Marks, K.; Turville, S.; Cooper, D.A.; Kelleher, A.D.; Suzuki, K. Novel RNA Duplex Locks HIV-1 in a Latent State via Chromatin-mediated Transcriptional Silencing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modified CoV siRNAs | Strand | Sequence (5′–3′) | Target Genes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiRNA-18 -OH | Sense Antisense | GCUACAUCACGAACGCUUU [dT][dT] AAAGCGUUCGUGAUGUAGCAA | Membrane | [20] |

| SiRNA-18 -1,4,10 G | Sense Antisense | GCUACAUCAGGAACGGUUA [dT][dT] AAAGCGUUCGUGAUGUAGC [dT][dT] | Membrane | [21] |

| SiRNA-18 -1,5,10 P | Sense Antisense | UCUAUAUCAUGAACGCUUU [dT][dT] AAAGCGUUCGUGAUGUAGC [dT][dT] | Membrane | [21,22] |

| SiRNA-18 -22 nt | Sense Antisense | GCUACAUCACGAACGCUUUCUU GAAAGCGUUCGUGAUGUAGCAA | Membrane | [21] |

| SiRNA-18 -6AG | Sense Antisense | GCUACGUCACGAACGCUUU [dT][dT] AAAGCGUUCGUGACGUAGC [dT][dT] | Membrane | [17] |

| SiRNA-18 -Ome AS 4,5,6 | Sense Antisense | GCUACAUCACGAACGCUUU [dT][dT] AAAmGmCmGUUCGUGAUGUAGC [dT][dT] | Membrane | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| SiRNA-25 -OH | Sense Antisense | GGGUUGCAACUGAGGGAGC [dT][dT] GCUCCCUCAGUUGCAACCCAU | Nucleocapsid | [20] |

| SiRNA-25 -1,4,10 G | Sense Antisense | GGGUUGCAAGUGAGGCAGG [dT][dT] GCUCCCUCAGUUGCAACCC [dT][dT] | Nucleocapsid | [21] |

| SiRNA-25 -1,7,10 P | Sense Antisense | UGGUUGUAAUUGAGGGAGC [dT][dT] GCUCCCUCAGUUGCAACCC [dT][dT] | Nucleocapsid | [21,22] |

| SiRNA-25 -22 nt | Sense Antisense | GGGUUGCAACUGAGGGAGCCUU GGCUCCCUCAGUUGCAACCCAU | Nucleocapsid | [21] |

| SiRNA-25 -14GU | Sense Antisense | GGGUUGCAACUGATGGAGC [dT][dT] GCUCCAUCAGUUGCAACCC [dT][dT] | Nucleocapsid | [17] |

| SiRNA-25 -Ome AS 4,5,6 | Sense Antisense | GGGUUGCAACUGAGGGAGC [dT][dT] GCUmCmCmCUCAGUUGCAACCC [dT][dT] | Nucleocapsid | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| SiRNA-27 -Ome AS 4,5,6 | Sense Antisense | CGAGAAAACACACGUCCAA [dT][dT] UUGmGmAmCGUGUGUUUUCUCG [dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| SiRNA-30 -OH | Sense Antisense | GGCAUUCAGUACGGUCGUA [dT][dT] UACGACCGUACUGAAUGCCUU | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [20] |

| SiRNA-30 -1,4,10 G | Sense Antisense | GGCAUUCAGAACGGUGGUC [dT][dT] UACGACCGUACUGAAUGCC [dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [21] |

| SiRNA-30 -1,7,11 P | Sense Antisense | UGCAUUUAGUAUGGUCGUA [dT][dT] UACGACCGUACUGAAUGCC [dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [21,22] |

| SiRNA-30 -22 nt | Sense Antisense | GGCAUUCAGUACGGUCGUAGUG CUACGACCGUACUGAAUGCCUU | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [21] |

| SiRNA-30 -Ome AS 2–8 | Sense Antisense | GGCAUUCAGUACGGUCGUA [dT][dT] UmAmCmGmAmCmCmGUACUGAAUGCC [dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| SiRNA-30 -Ome AS 4,5,6 | Sense Antisense | GGCAUUCAGUACGGUCGUA [dT][dT] UACmGmAmCCGUACUGAAUGCC [dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| SiRNA-30-OnpattroMods | Sense Antisense | G*mGC*A*mU*mUC*A*G*U*A*mCG*mGmUmCmGU*mA[dT][dT] U*A*C*G*A*C*mCG*U*A*C*U*G*A*A*U*mGC*C*[dT][dT] | ORF1ab (NSP1) | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Johansen, M.D.; Ledger, S.; Turville, S.; Thordarson, P.; Hansbro, P.M.; Kelleher, A.D.; Ahlenstiel, C.L. Respiratory Delivery of Highly Conserved Antiviral siRNAs Suppress SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311675

Zhang Y, Johansen MD, Ledger S, Turville S, Thordarson P, Hansbro PM, Kelleher AD, Ahlenstiel CL. Respiratory Delivery of Highly Conserved Antiviral siRNAs Suppress SARS-CoV-2 Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311675

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuan, Matt D. Johansen, Scott Ledger, Stuart Turville, Pall Thordarson, Philip M. Hansbro, Anthony D. Kelleher, and Chantelle L. Ahlenstiel. 2025. "Respiratory Delivery of Highly Conserved Antiviral siRNAs Suppress SARS-CoV-2 Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311675

APA StyleZhang, Y., Johansen, M. D., Ledger, S., Turville, S., Thordarson, P., Hansbro, P. M., Kelleher, A. D., & Ahlenstiel, C. L. (2025). Respiratory Delivery of Highly Conserved Antiviral siRNAs Suppress SARS-CoV-2 Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311675