Therapeutic Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Journey from Standard of Care to New Emerging Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Metastatic Prostate Cancer

2.1. Use of ADT in Metastic Prostate Cancer

2.2. Use of Androgen-Receptors Axis Targeted Therapies (ARATs) in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

2.2.1. Abiraterone Acetate

2.2.2. Enzalutamide, Apalutamide, Darolutamide

2.3. Use of Chemotherapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

2.3.1. Docetaxel

2.3.2. Androgen Deprivation Therapy + Docetaxel

2.3.3. Cabazitaxel

2.3.4. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy

2.4. Use of Radiopharmaceuticals in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: II and III Lines of Therapy

2.4.1. Radium-223

2.4.2. Lu-PSMA-617

2.5. Use of Target Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

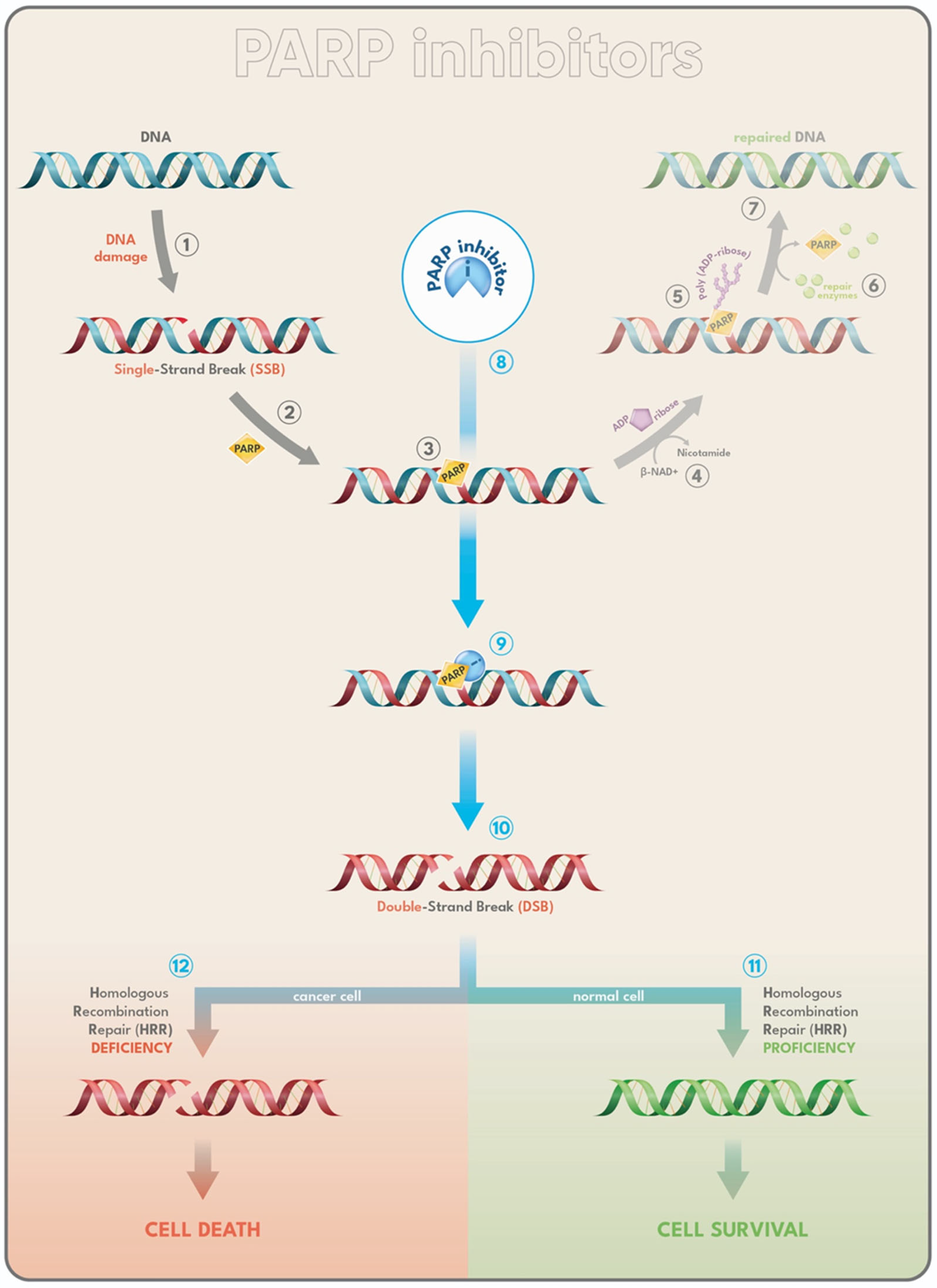

2.5.1. PARP-Inhibitors

Abiraterone-Prednisone Plus Olaparib

Abiraterone-Prednisone Plus Niraparib

Rucaparib

Enzalutamide Plus Talazoparib

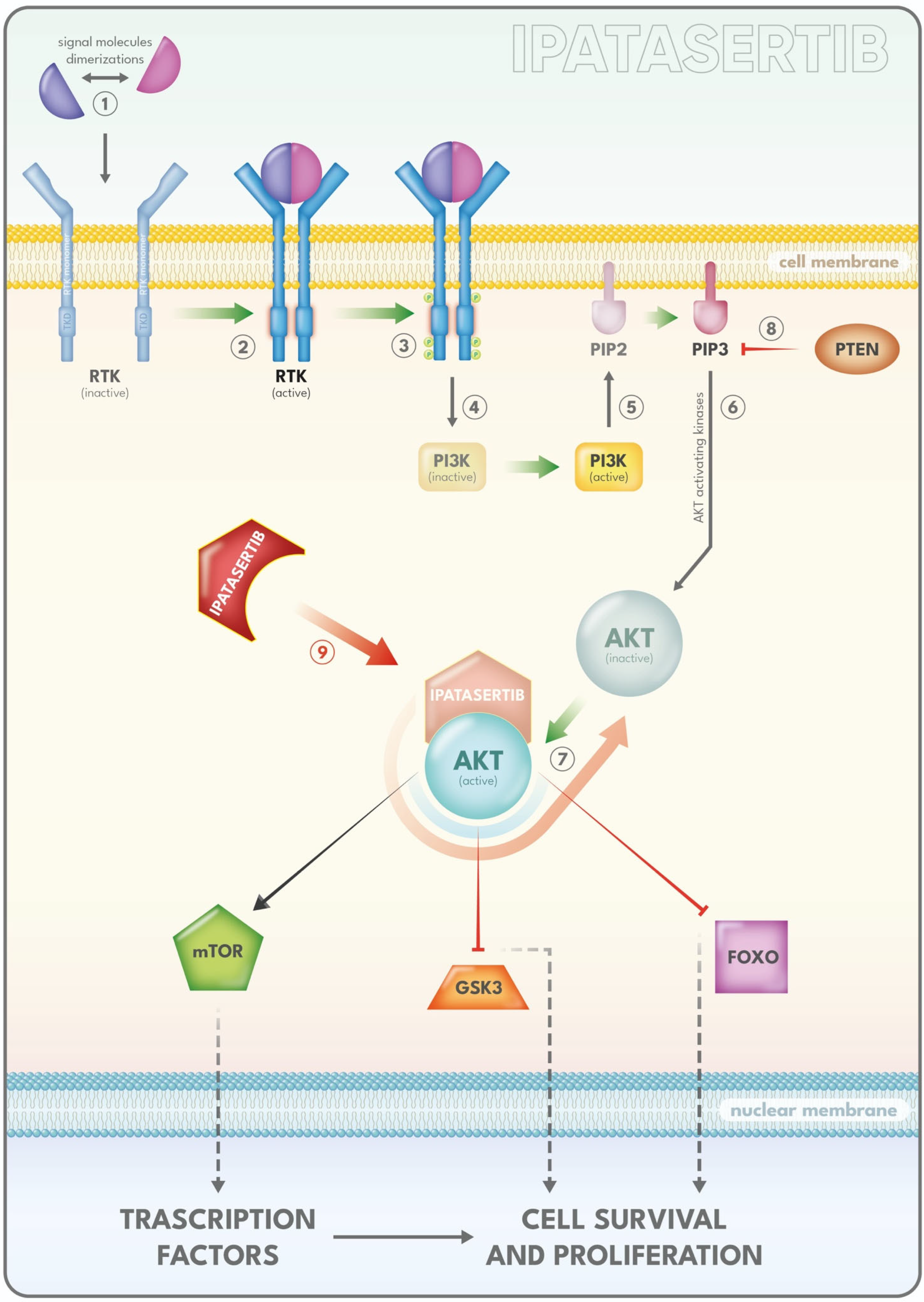

2.5.2. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors

Ipatasertib

Capivasertib

2.6. Other Targeted Therapies

2.7. New Frontiers in PCa

Immunotherapy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- Enhancement of cancer cell ICD

- Reversal of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME)

- Adoptive T cell therapy

- Therapeutic cancer vaccines

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. Prostate Cancer Cases Might Rise to 3 Million Globally by 2040. JAMA 2024, 331, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandini, M.; Pompe, R.S.; Marchioni, M.; Tian, Z.; Gandaglia, G.; Fossati, N.; Tilki, D.; Graefen, M.; Montorsi, F.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy reduce prostate cancer mortality in elderly patients: A population-based propensity score adjusted analysis. World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillessen, S.; Bossi, A.; Davis, I.D.; de Bono, J.; Fizazi, K.; James, N.D.; Mottet, N.; Shore, N.; Small, E.; Smith, M.; et al. Management of Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer. Part I: Intermediate-/High-risk and Locally Advanced Disease, Biochemical Relapse, and Side Effects of Hormonal Treatment: Report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2022. Eur. Urol. 2023, 83, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasegaran, T.; Oliveira, N. Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Advances in Treatment and Symptom Management. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 914–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilki, D.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II-2024 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioni, M.; Di Nicola, M.; Primiceri, G.; Novara, G.; Castellan, P.; Paul, A.K.; Veccia, A.; Autorino, R.; Cindolo, L.; Schips, L. New Antiandrogen Compounds Compared to Docetaxel for Metastatic Hormone Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Results from a Network Meta-Analysis. J. Urol. 2020, 203, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, L.; Boccon-Gibod, L.; Shore, N.D.; Andreou, C.; Persson, B.-E.; Cantor, P.; Jensen, J.-K.; Olesen, T.K.; Schröder, F.H. The efficacy and safety of degarelix: A 12-month, comparative, randomized, open-label, parallel-group phase III study in patients with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008, 102, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sountoulides, P.; Rountos, T. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: Prevention and management. ISRN Urol. 2013, 2013, 240108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Würnschimmel, C.; Nocera, L.; Collà Ruvolo, C.; Tian, Z.; Shariat, S.F.; Saad, F.; Briganti, A.; Tilki, D.; Graefen, M.; et al. Overall Survival After Systemic Treatment in High-volume Versus Low-volume Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bria, E.; Cuppone, F.; Giannarelli, D.; Milella, M.; Ruggeri, E.M.; Sperduti, I.; Pinnarò, P.; Terzoli, E.; Cognetti, F.; Carlini, P. Does hormone treatment added to radiotherapy improve outcome in locally advanced prostate cancer? Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancer 2009, 115, 3446–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oefelein, M.G.; Feng, A.; Scolieri, M.J.; Ricchiutti, D.; Resnick, M.I. Reassessment of the definition of castrate levels of testosterone: Implications for clinical decision making. Urology 2000, 56, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, L.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Ding, K.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Higano, C.S.; Horwitz, E.M.; Malone, S.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Crook, J.M. A phase III randomized trial comparing intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for patients with PSA progression after radical therapy: NCIC CTG PR.7/SWOG JPR.7/CTSU JPR.7/UK Intercontinental Trial CRUKE/01/013. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29 (Suppl. S3), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.; Ouk, S.; Clegg, N.J.; Chen, Y.; Watson, P.A.; Arora, V.; Wongvipat, J.; Smith-Jones, P.M.; Yoo, D.; Kwon, A.; et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science 2009, 324, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, G.; Arcangeli, S.; Fionda, B.; Munoz, F.; Tebano, U.; Durante, E.; Tucci, M.; Bortolus, R.; Muraro, M.; Rinaldi, G.; et al. A Systematic Review and a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials’ Control Groups in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC). Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Tangen, C.M.; Berry, D.L.; Higano, C.S.; Crawford, E.D.; Liu, G.; Wilding, G.; Prescott, S.; Kanaga Sundaram, S.; Small, E.J.; et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunath, F.; Jensen, K.; Pinart, M.; Kahlmeyer, A.; Schmidt, S.; Price, C.L.; Lieb, V.; Dahm, P. Early versus deferred standard androgen suppression therapy for advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD003506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.-N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravis, G.; Boher, J.-M.; Chen, Y.-H.; Liu, G.; Fizazi, K.; Carducci, M.A.; Oudard, S.; Joly, F.; Jarrard, D.M.; Soulie, M.; et al. Burden of Metastatic Castrate Naive Prostate Cancer Patients, to Identify Men More Likely to Benefit from Early Docetaxel: Further Analyses of CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 Studies. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, C.E.; Chen, Y.-H.; Carducci, M.A.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Hahn, N.M.; Shevrin, D.H.; Dreicer, R.; Hussain, M.; Eisenberger, M.; et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase III E3805 CHAARTED Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, A.; Pfail, J.; Montorsi, F.; Galsky, M.D.; Oh, W.K. Surrogate endpoints for overall survival for patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in the CHAARTED trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.W.; Ali, A.; Ingleby, F.C.; Hoyle, A.; Amos, C.L.; Attard, G.; Brawley, C.D.; Calvert, J.; Chowdhury, S.; Cook, A.; et al. Addition of docetaxel to hormonal therapy in low- and high-burden metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer: Long-term survival results from the STAMPEDE trial. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1992–2003, Correction in Ann. Oncol 2020, 31, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravis, G.; Boher, J.-M.; Joly, F.; Soulié, M.; Albiges, L.; Priou, F.; Latorzeff, I.; Delva, R.; Krakowski, I.; Laguerre, B.; et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) Plus Docetaxel Versus ADT Alone in Metastatic Non castrate Prostate Cancer: Impact of Metastatic Burden and Long-term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 Trial. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; Sydes, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Spears, M.R.; Ritchie, A.W.S.; Parker, C.C.; Russell, J.M.; Attard, G.; et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): Survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Sayyid, R.; Saad, F.; Sun, Y.; Lajkosz, K.; Ong, M.; Klaassen, Z.; Malone, S.; Spratt, D.E.; Wallis, C.J.D.; et al. Addition of Docetaxel to Androgen Receptor Axis-targeted Therapy and Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: A Network Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, Y.; Goto, T.; Akamatsu, S.; Yamasaki, T.; Inoue, T.; Ogawa, O.; Kobayashi, T. Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Refractory to Second-Generation Androgen Receptor Axis-Targeted Agents: Opportunities and Challenges. Cancers 2018, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, T.; Yang, J.C.; Gao, A.C.; Evans, C.P. Mechanisms of resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Transl. Androl. Urol. 2015, 4, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Richards, J.; de Bono, J.S. New strategies in metastatic prostate cancer: Targeting the androgen receptor signaling pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.J.; Cheng, M.L. Abiraterone acetate for the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2013, 14, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. FDA Approves Abiraterone Acetate in Combination with Prednisone for High-Risk Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abiraterone-acetate-combination-prednisone-high-risk-metastatic-castration-sensitive (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Zytiga. 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zytiga (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ryan, C.J.; Smith, M.R.; de Bono, J.S.; Molina, A.; Logothetis, C.J.; de Souza, P.; Fizazi, K.; Mainwaring, P.; Piulats, J.M.; Ng, S.; et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 138–148, Correction in N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathkopf, D.E.; Smith, M.R.; de Bono, J.S.; Logothetis, C.J.; Shore, N.D.; de Souza, P.; Fizazi, K.; Mulders, P.F.A.; Mainwaring, P.; Hainsworth, J.D.; et al. Updated interim efficacy analysis and long-term safety of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients without prior chemotherapy (COU-AA-302). Eur. Urol. 2014, 66, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, A.P.; Ali, A.; James, N.D.; Cook, A.; Parker, C.C.; de Bono, J.S.; Attard, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Cross, W.R.; Dearnaley, D.P.; et al. Abiraterone in “High-” and “Low-risk” Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.J.; Smith, M.R.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Mulders, P.F.A.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; Logothetis, C.J.; Shore, N.D.; Small, E.J.; et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): Final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; de Bono, J.S.; Spears, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Ritchie, A.W.S.; Amos, C.L.; Gilson, C.; Jones, R.J.; et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska, L.; Tierney, J.; Burdett, S.; Mason, M.; Parmar, M.; Sweeney, C.; Vale, C.; Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Abiraterone for Hormone-Sensitive Metastatic Prostate Cancer. PROSPERO 2024. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42017058300 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Shiota, M.; Eto, M. Current status of primary pharmacotherapy and future perspectives toward upfront therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2016, 23, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Maldonado, X.; Foulon, S.; Roubaud, G.; McDermott, R.S.; Flechon, A.; Tombal, B.F.; Supiot, S.; Berthold, D.R.; Ronchin, P.; et al. A phase 3 trial with a 2 × 2 factorial design of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and/or local radiotherapy in men with de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): First results of PEACE-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Foulon, S.; Carles, J.; Roubaud, G.; McDermott, R.; Fléchon, A.; Tombal, B.; Supiot, S.; Berthold, D.; Ronchin, P.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet 2022, 399, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyerabend, S.; Saad, F.; Li, T.; Ito, T.; Diels, J.; Van Sanden, S.; De Porre, P.; Roiz, J.; Abogunrin, S.; Koufopoulou, M.; et al. Survival benefit, disease progression and quality-of-life outcomes of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus docetaxel in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: A network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 103, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boevé, L.M.; Hulshof, M.C.; Vis, A.N.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Twisk, J.W.; Witjes, W.P.; Delaere, K.P.; van Moorselaar, R.J.A.; Verhagen, P.C.; van Andel, G. Effect on Survival of Androgen Deprivation Therapy Alone Compared to Androgen Deprivation Therapy Combined with Concurrent Radiation Therapy to the Prostate in Patients with Primary Bone Metastatic Prostate Cancer in a Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial: Data from the HORRAD Trial. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossi, A.; Foulon, S.; Maldonado, X.; Sargos, P.; MacDermott, R.; Kelly, P.; Fléchon, A.; Tombal, B.; Supiot, S.; Berthold, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of prostate radiotherapy in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet 2024, 404, 2065–2076, Correction in Lancet 2025, 405, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrikidou, A.; Brureau, L.; Casenave, J.; Albiges, L.; Di Palma, M.; Patard, J.-J.; Baumert, H.; Blanchard, P.; Bossi, A.; Kitikidou, K.; et al. Locoregional symptoms in patients with de novo metastatic prostate cancer: Morbidity, management, and disease outcome. Urol. Oncol. 2015, 33, 202.e9–202.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Nubeqa. 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/nubeqa (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Xtandi. 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/xtandi (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Erleada. 2019. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/erleada (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Keam, S.J. Rezvilutamide: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Stein, C.A.; Sartor, O. Enzalutamide for the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2013, 14, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurth, C.; Sandmann, S.; Trummel, D.; Seidel, D.; Gieschen, H. Blood-brain barrier penetration of [14C]darolutamide compared with [14C]enzalutamide in rats using whole body autoradiography. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.M.; Armstrong, A.J.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Loriot, Y.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carles, J.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.-E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; de Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Azad, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Iguchi, T.; Shore, N.D.; et al. ARCHES: A Randomized, Phase III Study of Androgen Deprivation Therapy With Enzalutamide or Placebo in Men With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombal, B.; Borre, M.; Rathenborg, P.; Werbrouck, P.; Van Poppel, H.; Heidenreich, A.; Iversen, P.; Braeckman, J.; Heracek, J.; Baron, B.; et al. Long-Term Antitumor Activity and Safety of Enzalutamide Monotherapy in Hormone Naïve Prostate Cancer: 3-Year Open Label Followup Results. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Veiga, F.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Azad, A.A.; Iguchi, T.; Villers, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Shore, N.D.; Rosbrook, B.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Enzalutamide in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer in Patients Aged <75 and ≥75 Years: ARCHES Post Hoc Analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 7, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciarello, G.; Sternberg, C.N. Treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with enzalutamide. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 106, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Cheung, L.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Frydenberg, M.; Horvath, L.G.; Joshua, A.M.; et al. Testosterone suppression plus enzalutamide versus testosterone suppression plus standard antiandrogen therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (ENZAMET): An international, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afferi, L.; Longoni, M.; Moschini, M.; Gandaglia, G.; Morgans, A.K.; Cathomas, R.; Mattei, A.; Breda, A.; Scarpa, R.M.; Papalia, R.; et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treated with androgen receptor signaling inhibitors: The role of combination treatment therapy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Lin, P.; Tombal, B.; Saad, F.; Higano, C.S.; Joshua, A.M.; Parli, T.; Rosbrook, B.; van Os, S.; Beer, T.M. Five-year Survival Prediction and Safety Outcomes with Enzalutamide in Men with Chemotherapy-naïve Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer from the PREVAIL Trial. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.M.; Armstrong, A.J.; Rathkopf, D.; Loriot, Y.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Evans, C.P.; Kim, C.-S.; Kimura, G.; et al. Enzalutamide in Men with Chemotherapy-naïve Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Extended Analysis of the Phase 3 PREVAIL Study. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.P.; Higano, C.S.; Keane, T.; Andriole, G.; Saad, F.; Iversen, P.; Miller, K.; Kim, C.-S.; Kimura, G.; Armstrong, A.J.; et al. The PREVAIL Study: Primary Outcomes by Site and Extent of Baseline Disease for Enzalutamide-treated Men with Chemotherapy-naïve Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Klotz, L.; Siemens, D.R.; Villers, A.; Ivanescu, C.; Holmstrom, S.; Baron, B.; Wang, F.; Lin, P.; et al. Impact of Enzalutamide Compared with Bicalutamide on Quality of Life in Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Additional Analyses from the TERRAIN Randomised Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Agarwal, N.; Bhaumik, A.; Lefresne, F.; Karsh, L.I.; Gomes, A.J.P.d.S.; Soto, Á.J.; Given, R.W.; Brookman-May, S.D.; Mundle, S.D.; et al. Apalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy in clinical subgroups of patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: A subgroup analysis of the randomised clinical TITAN study. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 193, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Sun, Y.; Chi, K.N.; Ong, M.; Malone, S.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Kishan, A.U.; Malone, J.; Swami, U.; Gebrael, G.; et al. Early Prostate-Specific Antigen Response by 6 Months Is Predictive of Treatment Effect in Metastatic Hormone Sensitive Prostate Cancer: An Exploratory Analysis of the TITAN Trial. J. Urol. 2024, 212, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Bjartell, A.; Agarwal, N.; Chung, B.; Given, R.; Gomes, A.P.d.S.; Merseburger, A.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Soto, Á.J.; Uemura, H.; et al. Deep, rapid, and durable prostate-specific antigen decline with apalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy is associated with longer survival and improved clinical outcomes in TITAN patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuokaya, W.; Yanagisawa, T.; Mori, K.; Urabe, F.; Rajwa, P.; Briganti, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Kimura, T. Radiographic Progression Without Corresponding Prostate-specific Antigen Progression in Patients with Metastatic Castration-sensitive Prostate Cancer Receiving Apalutamide: Secondary Analysis of the TITAN Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, N.; McQuarrie, K.; Bjartell, A.; Chowdhury, S.; de Santana Gomes, A.J.P.; Chung, B.H.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Soto, Á.J.; Merseburger, A.S.; Uemura, H.; et al. Health-related quality of life after apalutamide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (TITAN): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Chowdhury, S.; Agarwal, N.; Karsh, L.I.; Oudard, S.; Gartrell, B.A.; Feyerabend, S.; Saad, F.; Pieczonka, C.M.; Chi, K.N.; et al. Apalutamide efficacy, safety and wellbeing in older patients with advanced prostate cancer from Phase 3 randomised clinical studies TITAN and SPARTAN. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Gu, W.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, S.; Shi, B.; Sun, T.; Wei, S.; Weng, Z.; Xia, S.; et al. Correlation of PSA and survival in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treated with rezvilutamide plus ADT in the CHART trial. Med 2025, 6, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Han, W.; Luo, H.; Zhou, F.; He, D.; Ma, L.; Guo, H.; Liang, C.; Chong, T.; Jiang, J.; et al. Rezvilutamide versus bicalutamide in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with high-volume, metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (CHART): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Hussain, M.; Saad, F.; Fizazi, K.; Sternberg, C.N.; Crawford, E.D.; Kopyltsov, E.; Park, C.H.; Alekseev, B.; Montesa-Pino, Á.; et al. Darolutamide and Survival in Metastatic, Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.; Vjaters, E.; Shore, N.; Olmos, D.; Xing, N.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Cesar de Andrade Mota, A.; Salman, P.; Jievaltas, M.; Ulys, A.; et al. Darolutamide in Combination With Androgen-Deprivation Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer From the Phase III ARANOTE Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4271–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeh, B.; Wenzel, M.; Tian, Z.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Saad, F.; Steuber, T.; Graefen, M.; Tilki, D.; Herout, R.; Thomas, C.; et al. Triplet or Doublet Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer Patients: An Updated Network Meta-analysis Including ARANOTE Data. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 11, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guercio, B.J.; Sahasrabudhe, D. Current Trends in Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshad, S.; Sidhu, A.K.; Khan, N.; Naoum, A.; Emmenegger, U. Metronomic Chemotherapy for Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, W.; Dong, B.; Xin, Z.; Ji, Y.; Su, R.; Shen, K.; Pan, J.; Wang, Q.; Xue, W. Docetaxel remodels prostate cancer immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4965–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannock, I.F.; de Wit, R.; Berry, W.R.; Horti, J.; Pluzanska, A.; Chi, K.N.; Oudard, S.; Théodore, C.; James, N.D.; Turesson, I.; et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrylak, D.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Hussain, M.H.A.; Lara, P.N.; Jones, J.A.; Taplin, M.E.; Burch, P.A.; Berry, D.; Moinpour, C.; Kohli, M.; et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Song, X.-L.; Li, X.-A.; Chen, M.; Guo, J.; Yang, D.-H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, S.-C. Current therapy and drug resistance in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Drug Resist. Updates 2023, 68, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.S.; Oudard, S.; Ozguroglu, M.; Hansen, S.; Machiels, J.-P.; Kocak, I.; Gravis, G.; Bodrogi, I.; Mackenzie, M.J.; Shen, L.; et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, M.Y.; Scher, H.I. Lessons from the SWITCH trial: Changing glucocorticoids in the management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavaud, P.; Gravis, G.; Foulon, S.; Joly, F.; Oudard, S.; Priou, F.; Latorzeff, I.; Mourey, L.; Soulié, M.; Delva, R.; et al. Anticancer Activity and Tolerance of Treatments Received Beyond Progression in Men Treated Up-front with Androgen Deprivation Therapy With or Without Docetaxel for Metastatic Castration-naïve Prostate Cancer in the GETUG-AFU 15 Phase 3 Trial. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, S.; Mercinelli, C.; Marandino, L.; Litterio, G.; Marchioni, M.; Schips, L. Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Insights on Current Therapy and Promising Experimental Drugs. Res. Rep. Urol. 2023, 2023, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrignaud, P.; Sémiond, D.; Lejeune, P.; Bouchard, H.; Calvet, L.; Combeau, C.; Riou, J.-F.; Commerçon, A.; Lavelle, F.; Bissery, M.-C. Preclinical antitumor activity of cabazitaxel, a semisynthetic taxane active in taxane-resistant tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 2973–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimit, A.; Adebali, O.; Sancar, A.; Jiang, Y. Differential damage and repair of DNA-adducts induced by anti-cancer drug cisplatin across mouse organs. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Yao, Q. Platinum-based drugs for cancer therapy and anti-tumor strategies. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2115–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderden, R.A.; Hall, M.D.; Hambley, T.W. The Discovery and Development of Cisplatin. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, M.; Lapucci, A.; Nobili, S.; De Gennaro Aquino, I.; Vascotto, I.A.; Antonuzzo, L.; Villari, D.; Nesi, G.; Mini, E.; Roviello, G. Platinum-based chemotherapy in metastatic prostate cancer: What possibilities? Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2024, 93, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.M.; Barnett, E.; Nauseef, J.T.; Nguyen, B.; Stopsack, K.H.; Wibmer, A.; Flynn, J.R.; Heller, G.; Danila, D.C.; Rathkopf, D.; et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer With DNA Repair Gene Alterations. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Omlin, A.; Higano, C.; Sweeney, C.; Martinez Chanza, N.; Mehra, N.; Kuppen, M.C.P.; Beltran, H.; Conteduca, V.; Vargas Pivato de Almeida, D.; et al. Activity of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer With and Without DNA Repair Gene Aberrations. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2021692, Correction in JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2029176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, M.M.; Spisák, S.; Jia, L.; Cronin, A.M.; Csabai, I.; Ledet, E.; Sartor, A.O.; Rainville, I.; O’Connor, E.P.; Herbert, Z.T.; et al. The association between germline BRCA2 variants and sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy among men with metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 3532–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.H.; Pritchard, C.C.; Boyd, T.; Nelson, P.S.; Montgomery, B. Biallelic Inactivation of BRCA2 in Platinum-sensitive Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, A.M.; Shen, L.; Tapia, E.L.N.; Lu, J.-F.; Chen, H.-C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Troncoso, P.; Corn, P.; et al. Combined Tumor Suppressor Defects Characterize Clinically Defined Aggressive Variant Prostate Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corn, P.G.; Heath, E.I.; Zurita, A.; Ramesh, N.; Xiao, L.; Sei, E.; Li-Ning-Tapia, E.; Tu, S.-M.; Subudhi, S.K.; Wang, J.; et al. Cabazitaxel plus carboplatin for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers: A randomised, open-label, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1432–1443, Correction in Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, K.; Nonomura, N. Systemic Therapies for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: An Updated Review. World J. Men’s Health 2023, 41, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Castro, E.; Fizazi, K.; Heidenreich, A.; Ost, P.; Procopio, G.; Tombal, B.; Gillessen, S.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, O.; de Bono, J.; Chi, K.N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nordquist, L.T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G.; et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-H.; Dai, J.-D.; Zhang, X.-M.; Zhao, J.-G.; Sun, G.-X.; Zeng, Y.-H.; Zeng, H.; Xu, N.-W.; Zeng, H.; Shen, P.-F. The safety of radium-223 combined with new-generation hormonal agents in bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Asian J. Androl. 2023, 25, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.-T.; Huang, H.; Gu, D.; Ren, S. Targeting signaling pathways in prostate cancer: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.J.; Corey, E.; Guise, T.A.; Gulley, J.L.; Kevin Kelly, W.; Quinn, D.I.; Scholz, A.; Sgouros, G. Radium-223 mechanism of action: Implications for use in treatment combinations. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, O.; Coleman, R.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; et al. Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: Results from a phase 3, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.M.; Abramowitz, E.; Sierra-Scacalossi, L. Integrating radium-223 therapy into the management of metastatic prostate cancer care: A plain language summary. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, A.; Gillessen, S.; Heinrich, D.; Keizman, D.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Carles, J.; Wirth, M.; Miller, K.; Reeves, J.; Seger, M.; et al. Radium-223 in asymptomatic patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases treated in an international early access program. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Frantellizzi, V.; Bulzonetti, N.; De Vincentis, G. Reversibility of castration resistance status after Radium-223 dichloride treatment: Clinical evidence and review of the literature. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osvaldo, G.-P.F.; Salvador, M.-O.S.; Zael, S.-R.; Nora, S.-M. Radium-223 IN metastatic hormone-sensitive high-grade prostate cancer: Initial experience. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2017, 7, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, G.J.; Parker, C.; Chua, S.; Johnson, B.; Aksnes, A.-K.; Lewington, V.J. 18F-fluoride PET: Changes in uptake as a method to assess response in bone metastases from castrate-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with 223Ra-chloride (Alpharadin). EJNMMI Res. 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenter, V.; Herlemann, A.; Fendler, W.P.; Ilhan, H.; Tirichter, N.; Bartenstein, P.; Stief, C.G.; la Fougère, C.; Albert, N.L.; Rominger, A.; et al. Radium-223 for primary bone metastases in patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 44131–44140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonollo, F.; Thalmann, G.N.; Kruithof-de Julio, M.; Karkampouna, S. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Prostate Cancer Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.G.; Jain, S.; Mitchell, D.M.; Hounsell, A.; Biggart, S.; O’Sullivan, J.M. First Results from the ADRRAD Trial—Combination Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT), Whole Pelvis Radiotherapy (WPRT) and Radium 223 in Recently Diagnosed Metastatic Hormone Sensitive Prostate Cancer (MHSPCa). Clin. Oncol. 2018, 30, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandapani, S.; Dorff, T.; Kortylewski, M.; Frankel, P.; Twardowski, P. Radium 223 Dichloride in Combination with Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Patients with Stage IV Oligometastatic Castration Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Clinical Trial in Progress. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 104, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundahl, N.; Tree, A.; Parker, C. The Emerging Role of Local Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, S.; Boevé, L.M.; Ingleby, F.C.; Fisher, D.J.; Rydzewska, L.H.; Vale, C.L.; van Andel, G.; Clarke, N.W.; Hulshof, M.C.; James, N.D.; et al. Prostate Radiotherapy for Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: A STOPCAP Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, P.; Reynders, D.; Decaestecker, K.; Fonteyne, V.; Lumen, N.; De Bruycker, A.; Lambert, B.; Delrue, L.; Bultijnck, R.; Claeys, T.; et al. Surveillance or Metastasis-Directed Therapy for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer Recurrence: A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, S.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Oligometastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siva, S.; Bressel, M.; Murphy, D.G.; Shaw, M.; Chander, S.; Violet, J.; Tai, K.H.; Udovicich, C.; Lim, A.; Selbie, L.; et al. Stereotactic Abative Body Radiotherapy (SABR) for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, N.; Carles, J.; McDermott, R.; Agarwal, N.; Tombal, B. Treatment intensification with radium-223 plus enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1460212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; de Almeida Luz, M.; De Giorgi, U.; Gleave, M.; Gotto, G.T.; Pieczonka, C.M.; Haas, G.P.; Kim, C.-S.; Ramirez-Backhaus, M.; Rannikko, A.; et al. Improved Outcomes with Enzalutamide in Biochemically Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.L.; Haley, C.; Beckett, M.L.; Schellhammer, P.F. Expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen in normal, benign, and malignant prostate tissues. Urol. Oncol. 1995, 1, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benešová, M.; Schäfer, M.; Bauder-Wüst, U.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Kratochwil, C.; Mier, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Kopka, K.; Eder, M. Preclinical Evaluation of a Tailor-Made DOTA-Conjugated PSMA Inhibitor with Optimized Linker Moiety for Imaging and Endoradiotherapy of Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, C.A.; Mease, R.C.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Ravert, H.T.; Dannals, R.F.; Olszewski, R.T.; Heston, W.D.; Kozikowski, A.P.; Pomper, M.G. Radiolabeled small-molecule ligands for prostate-specific membrane antigen: In vivo imaging in experimental models of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4022–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barinka, C.; Byun, Y.; Dusich, C.L.; Banerjee, S.R.; Chen, Y.; Castanares, M.; Kozikowski, A.P.; Mease, R.C.; Pomper, M.G.; Lubkowski, J. Interactions between human glutamate carboxypeptidase II and urea-based inhibitors: Structural characterization. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7737–7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozikowski, A.P.; Nan, F.; Conti, P.; Zhang, J.; Ramadan, E.; Bzdega, T.; Wroblewska, B.; Neale, J.H.; Pshenichkin, S.; Wroblewski, J.T. Design of remarkably simple, yet potent urea-based inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (NAALADase). J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Hetzheim, H.; Kratochwil, C.; Benesova, M.; Eder, M.; Neels, O.C.; Eisenhut, M.; Kübler, W.; Holland-Letz, T.; Giesel, F.L.; et al. The Theranostic PSMA Ligand PSMA-617 in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer by PET/CT: Biodistribution in Humans, Radiation Dosimetry, and First Evaluation of Tumor Lesions. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pene, F.; Courtine, E.; Cariou, A.; Mira, J.-P. Toward theragnostics. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, S50-58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratochwil, C.; Giesel, F.L.; Stefanova, M.; Benešová, M.; Bronzel, M.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Mier, W.; Eder, M.; Kopka, K.; Haberkorn, U. PSMA-Targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer with 177Lu-Labeled PSMA-617. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, R.; Seitzer, K.; Herrmann, K.; Kessel, K.; Schäfers, M.; Kleesiek, J.; Weckesser, M.; Boegemann, M.; Rahbar, K. Analysis of PSMA expression and outcome in patients with advanced Prostate Cancer receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7812–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, S.P.; Violet, J.; Sandhu, S.; Iravani, A.; Akhurst, T.; Kong, G.; Ravi Kumar, A.; Murphy, D.G.; Williams, S.G.; Hicks, R.J.; et al. Poor Outcomes for Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer with Low Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Expression Deemed Ineligible for 177Lu-labelled PSMA Radioligand Therapy. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buteau, J.P.; Martin, A.J.; Emmett, L.; Iravani, A.; Sandhu, S.; Joshua, A.M.; Francis, R.J.; Zhang, A.Y.; Scott, A.M.; Lee, S.-T.; et al. PSMA and FDG-PET as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in patients given [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): A biomarker analysis from a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, L.; Crumbaker, M.; Ho, B.; Willowson, K.; Eu, P.; Ratnayake, L.; Epstein, R.; Blanksby, A.; Horvath, L.; Guminski, A.; et al. Results of a Prospective Phase 2 Pilot Trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Therapy for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Including Imaging Predictors of Treatment Response and Patterns of Progression. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 17, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, K.; Schmidt, M.; Heinzel, A.; Eppard, E.; Bode, A.; Yordanova, A.; Claesener, M.; Ahmadzadehfar, H. Response and Tolerability of a Single Dose of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.H.; Morris, M.J.; Hesterman, J.; Kendi, A.T.; Rahbar, K.; Wei, X.X.; Fang, B.; Adra, N.; Garje, R.; Michalski, J.M.; et al. Quantitative 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET and Clinical Outcomes in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Following 177Lu-PSMA-617 (VISION Trial). Radiology 2024, 312, e233460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Krause, B.J.; Rahbar, K.; Chi, K.N.; Morris, M.J.; Sartor, O.; Tagawa, S.T.; Kendi, A.T.; Vogelzang, N.; et al. Health-related quality of life and pain outcomes with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 plus standard of care versus standard of care in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (VISION): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Eiber, M.; Sparks, R.; Baca, N.; Krause, B.J.; Lassmann, M.; Jentzen, W.; Tang, J.; Chicco, D.; et al. Renal and Multiorgan Safety of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer in the VISION Dosimetry Substudy. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofman, M.S.; Emmett, L.; Violet, J.; Zhang, A.Y.; Lawrence, N.J.; Stockler, M.; Francis, R.J.; Iravani, A.; Williams, S.; Azad, A.; et al. TheraP: A randomized phase 2 trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 theranostic treatment vs cabazitaxel in progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (Clinical Trial Protocol ANZUP 1603). BJU Int. 2019, 124 (Suppl. S1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.W.; Singh, A.; Kulkarni, H.R.; Niepsch, K.; Billah, B.; Baum, R.P. Clinical Outcomes of 177Lu-PSMA Radioligand Therapy in Earlier and Later Phases of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Grouped by Previous Taxane Chemotherapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.S.; Emmett, L.; Sandhu, S.; Iravani, A.; Buteau, J.P.; Joshua, A.M.; Goh, J.C.; Pattison, D.A.; Tan, T.H.; Kirkwood, I.D.; et al. Overall survival with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): Secondary outcomes of a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UROONCO. Phase III Trial of [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 in Taxane-Naive Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (PSMAfore). Available online: https://uroonco.uroweb.org/publication/phase-iii-trial-of-177lulu-psma-617-in-taxane-naive-patients-with-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer-psmafore/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Rahbar, K.; Boegemann, M. The Imperative for Comparative Studies in Nuclear Medicine: Elevating 177Lu-PSMA-617 in the Treatment Paradigm for mCRPC. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 224–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Gomes, A.J.P.D.S.; Given, R.; Soto, A.J.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroglu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, N.; George, D.J.; Abernethy, A.P.; Dolan, C.M.; Oestreicher, N.; Flanders, S.; Dorff, T.B. Patient experience in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: State of the science. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016, 19, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congregado, B.; Rivero, I.; Osmán, I.; Sáez, C.; Medina López, R. PARP Inhibitors: A New Horizon for Patients with Prostate Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.H.; Sokolova, A.O.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Small, E.J.; Higano, C.S. Germline and Somatic Mutations in Prostate Cancer for the Clinician. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergengren, O.; Pekala, K.R.; Matsoukas, K.; Fainberg, J.; Mungovan, S.F.; Bratt, O.; Bray, F.; Brawley, O.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Mucci, L.; et al. 2022 Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, M.; Schreiber, V.; Dantzer, F. The diverse roles and clinical relevance of PARPs in DNA damage repair: Current state of the art. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 84, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.Y.; Tan, K.V.; Cornelissen, B. PARP Inhibitors in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, R.; Kraus, W.L. The PARP side of the nucleus: Molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, D. PARP and PARG inhibitors in cancer treatment. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 360–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, M.; Fujiki, H.; Marks, P.A.; Sugimura, T. Induction of erythroid differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells by nicotinamide and related compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 6411–6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.H.; Shevach, J.W.; Castro, E.; Couch, F.J.; Domchek, S.M.; Eeles, R.A.; Giri, V.N.; Hall, M.J.; King, M.-C.; Lin, D.W.; et al. BRCA1, BRCA2, and Associated Cancer Risks and Management for Male Patients: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynahan, M.E.; Jasin, M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynahan, M.E.; Pierce, A.J.; Jasin, M. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, K.K.; Bajrami, I.; Taniguchi, T.; Lord, C.J. Synthetic lethality: The road to novel therapies for breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2016, 23, T39-55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Survival with Olaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Prostate Cancer, Version 1.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Akhras, A.; Hage Chehade, C.; Narang, A.; Swami, U. PARP Inhibitors in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Unraveling the Therapeutic Landscape. Life 2024, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, F.; Armstrong, A.J.; Thiery-Vuillemin, A.; Oya, M.; Loredo, E.; Procopio, G.; Janoski de Menezes, J.; Girotto, G.C.; Arslan, C.; Mehra, N.; et al. PROpel: Phase III trial of olaparib (ola) and abiraterone (abi) versus placebo (pbo) and abi as first-line (1L) therapy for patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. S11), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.W.; Armstrong, A.J.; Oya, M.; Shore, N.; Procopio, G.; Daniel Guedes, J.; Arslan, C.; Mehra, N.; Parnis, F.; Brown, E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Olaparib Plus Abiraterone Versus Placebo Plus Abiraterone in the First-line Treatment of Patients with Asymptomatic/Mildly Symptomatic and Symptomatic Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Analyses from the Phase 3 PROpel Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, C.; Strusi, A.; Arduini, D.; Maratta, M.G.; D’Agostino, F.; Sacco, E.; Totaro, A.; Bassi, P.; Iacovelli, R.; Tortora, G. Risk of Cardiovascular Toxicity and Hypertension in Prostate Cancer Patients Treated with the Combination of a PARP Inhibitor and Abiraterone: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 7, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, K.N.; Sandhu, S.; Smith, M.R.; Attard, G.; Saad, M.; Olmos, D.; Castro, E.; Roubaud, G.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Small, E.J.; et al. Niraparib plus abiraterone acetate with prednisone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and homologous recombination repair gene alterations: Second interim analysis of the randomized phase III MAGNITUDE trial. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Smith, M.R.; Efstathiou, E.; Attard, G.; Olmos, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Small, E.J.; Gomes, A.J.; Roubaud, G.; et al. Phase 3 MAGNITUDE study: First results of niraparib (NIRA) with abiraterone acetate and prednisone (AAP) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with and without homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. S12), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Akeega. 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/akeega (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Abida, W.; Patnaik, A.; Campbell, D.; Shapiro, J.; Bryce, A.H.; McDermott, R.; Sautois, B.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Bambury, R.M.; Voog, E.; et al. Rucaparib in Men With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Gene Alteration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Lee, S.H.; Zhang, J.; Signoretti, S.; Loda, M.; Roberts, T.M.; et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature 2008, 454, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorning, B.Y.; Dass, M.S.; Smalley, M.J.; Pearson, H.B. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway and Prostate Cancer: At the Crossroads of AR, MAPK, and WNT Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlind, M.P.; Hsieh, A.C. PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, K.D.; Corcoran, R.B.; Engelman, J.A. The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toren, P.; Zoubeidi, A. Targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in prostate cancer: Challenges and opportunities (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Pandolfi, P.P. The PTEN−PI3K Axis in Cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Cheng, H.; Roberts, T.M.; Zhao, J.J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Toker, A. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 2017, 169, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantley, L.C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 2002, 296, 1655–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, D.; Reid, A.H.M.; Yap, T.A.; de Bono, J.S. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4799–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braglia, L.; Zavatti, M.; Vinceti, M.; Martelli, A.M.; Marmiroli, S. Deregulated PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in prostate cancer: Still a potential druggable target? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaspishvili, T.; Berman, D.M.; Ross, A.E.; Scher, H.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Squire, J.A.; Lotan, T.L. Clinical implications of PTEN loss in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maekawa, S.; Takata, R.; Obara, W. Molecular Mechanisms of Prostate Cancer Development in the Precision Medicine Era: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.; Bracarda, S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Chi, K.N.; Olmos, D.; Sandhu, S.; Massard, C.; Matsubara, N.; Alekseev, B.; Parnis, F.; et al. Ipatasertib plus abiraterone and prednisolone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (IPATential150): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, J.S.; De Giorgi, U.; Rodrigues, D.N.; Massard, C.; Bracarda, S.; Font, A.; Arranz Arija, J.A.; Shih, K.C.; Radavoi, G.D.; Xu, N.; et al. Randomized Phase II Study Evaluating Akt Blockade with Ipatasertib, in Combination with Abiraterone, in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer with and without PTEN Loss. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AstraZeneca. A Phase III Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Study Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Capivasertib + Docetaxel Versus Placebo + Docetaxel as Treatment for Patients with Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC). 2025. Available online: https://onderzoekmetmensen.nl/en/node/53734/pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- AstraZeneca. A Phase III Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Study Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Capivasertib+Abiraterone Versus Placebo+Abiraterone as Treatment for Patients with DeNovo Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Characterised by PTEN Deficiency. 2025. Available online: https://onderzoekmetmensen.nl/en/node/52862/pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Abida, W.; Cyrta, J.; Heller, G.; Prandi, D.; Armenia, J.; Coleman, I.; Cieslik, M.; Benelli, M.; Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; et al. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11428–11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarra, A.; Innocenzi, M.; Ravaziol, M.; Minisola, F.; Alfarone, A.; Cattarino, S.; Monti, G.; Gentile, V.; Di Silverio, F. Neuroendocrine target therapies for prostate cancer. Urologia 2011, 78, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmgren, J.S.; Karavadia, S.S.; Wakefield, M.R. Unusual and underappreciated: Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Semin. Oncol. 2007, 34, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Epstein, J.I. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 95 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stultz, J.; Fong, L. How to turn up the heat on the cold immune microenvironment of metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.-R.; Lee, J.H.; Ponnazhagan, S. Revisiting Immunotherapy: A Focus on Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A. Could immunotherapy finally break through in prostate cancer? Nature 2022, 609, S42–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Naing, A.; Rolfo, C.; Hajjar, J. Biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade in cancer treatment. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2018, 130, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, A.P.; Antonarakis, E.S. Blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in advanced prostate cancer: Are we moving in the right direction? Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Yang, Z.; Miyamoto, H. Immunohistochemistry of immune checkpoint markers PD-1 and PD-L1 in prostate cancer. Medicine 2019, 98, e17257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.D.; Drake, C.G.; Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Bossi, A.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.M.; Krainer, M.; Houede, N.; Santos, R.; Mahammedi, H.; et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Cheng, M.L.; Armenia, J.; Middha, S.; Autio, K.A.; Vargas, H.A.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.J.; Danila, D.C.; Slovin, S.F.; et al. Analysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Pachynski, R.K.; Narayan, V.; Fléchon, A.; Gravis, G.; Galsky, M.D.; Mahammedi, H.; Patnaik, A.; Subudhi, S.K.; Ciprotti, M.; et al. Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Preliminary Analysis of Patients in the CheckMate 650 Trial. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 489–499.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrylak, D.P.; Ratta, R.; Matsubara, N.; Korbenfeld, E.; Gafanov, R.; Mourey, L.; Todenhöfer, T.; Gurney, H.; Kramer, G.; Bergman, A.M.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Docetaxel Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: The Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III KEYNOTE-921 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Warren, S.; Adjemian, S.; Agostinis, P.; Martinez, A.B.; Chan, T.A.; Coukos, G.; Demaria, S.; Deutsch, E.; et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000337, Correction in J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, B.L.; Yen, M.-L.; Hsu, P.-J.; Liu, K.-J.; Wang, C.-J.; Bai, C.-H.; Sytwu, H.-K. Multipotent Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Mediate Expansion of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells via Hepatocyte Growth Factor/c-Met and STAT3. Stem Cell Rep. 2013, 1, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maolake, A.; Izumi, K.; Shigehara, K.; Natsagdorj, A.; Iwamoto, H.; Kadomoto, S.; Takezawa, Y.; Machioka, K.; Narimoto, K.; Namiki, M.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote prostate cancer migration through activation of the CCL22–CCR4 axis. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 9739–9751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.H.; Beury, D.W.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Chapter Three—Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Critical Cells Driving Immune Suppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. In Advances in Cancer Research; Wang, X.-Y., Fisher, P.B., Eds.; Immunotherapy of Cancer; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 128, pp. 95–139. [Google Scholar]

- Raber, P.L.; Thevenot, P.; Sierra, R.; Wyczechowska, D.; Halle, D.; Ramirez, M.E.; Ochoa, A.C.; Fletcher, M.; Velasco, C.; Wilk, A.; et al. Subpopulations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair T cell responses through independent nitric oxide-related pathways. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 2853–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, D.M.S.; Pal, S.K.; Moreira, D.; Duttagupta, P.; Zhang, Q.; Won, H.; Jones, J.; D′APuzzo, M.; Forman, S.; Kortylewski, M. TLR9-Targeted STAT3 Silencing Abrogates Immunosuppressive Activity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells from Prostate Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3771–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.-A.; Joung, J.Y. T-Cell Engager Therapy in Prostate Cancer: Molecular Insights into a New Frontier in Immunotherapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yi, X.; Ai, J. mRNA vaccines for prostate cancer: A novel promising immunotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Therapy | mHSPC | Results Trial |

|---|---|---|

| ADT * + Second-generation of Androgen Synthesis Inhibitor (target CYP17) | Abiraterone + Prednisone – LATITUDE, STAMPEDE | – Both trials demonstrated improved OS and rPFS over ADT alone, particularly in high-risk or high-volume disease. |

| ADT * + Second generation of Androgen Receptor Inhibitor | (1) Enzalutamide – ENZAMET, ARCHES (2) Apalutamide – TITAN | (1)—Prolonged OS and rPFS; benefit consistent across disease volume and prior docetaxel use – Improved time to PSA progression (2)—Significant OS and rPFS benefit vs ADT alone – Manageable safety profile; consistent efficacy across subgroups |

| ADT * + Docetaxel + Abiraterone | Triplet therapy – PEACE-1 trial | – Improved OS and rPFS vs ADT + Docetaxel, especially in high-volume disease; no unexpected toxicities |

| ADT * + Docetaxel + Darolutamide | Triplet therapy – ARASENS trial | – Significant OS benefit vs ADT + Docetaxel; consistent efficacy across subgroups; safety similar to control |

| Disease Setting | Treatment Regimen | Clinical Trials | Results Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| mCRPC (1st line) | ADT * + Docetaxel | GETUG-AFU 15, CHAARTED | CHAARTED demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival (OS), particularly in patients with high-volume disease. GETUG-AFU 15 showed a similar trend but did not reach statistical significance for OS benefit. |

| mCRPC (2nd line) | ADT * + Cabazitaxel | TROPIC trial (Phase III) | TROPIC showed superior OS, progression-free survival (PFS), and PSA response rates compared with mitoxantrone in patients previously treated with docetaxel. Main toxicities included neutropenia and diarrhea, but overall treatment was manageable. |

| mCRPC (3rd line) | ADT * + Taxane + Platinum-based chemotherapy | Corn et al. (Phase I–II), RECARDO trial (Phase II) | Corn et al. and RECARDO trials indicated modest activity of taxane–platinum combinations in heavily pretreated mCRPC, with occasional durable responses in patients with aggressive or neuroendocrine features. Toxicity was acceptable with appropriate dose management. |

| PARP Inhibitor/Combination | Study | Most Common Adverse Events (All Grades) | Grade ≥ 3 Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olaparib + Abiraterone + Prednisone | PROpel (Phase III) | Anemia (52.5% asymptomatic, 45.2% symptomatic), fatigue/asthenia (34–46%), nausea (29–35%), diarrhea (16–22%), decreased appetite (10–18%), vomiting (14–18%), hypertension (13–14%), neutropenia (8–14%), musculoskeletal pain | Anemia ≥ 3: 14–20%, overall grade ≥ 3 AEs: 54–58% (vs. 42–46% placebo) |

| Niraparib + Abiraterone + Prednisone (AAP) | MAGNITUDE (Phase III) | Fatigue, nausea, anemia, hypertension, GI toxicities; overall manageable safety profile | Main ≥ 3 events: anemia, hypertension (higher in HRR+ subgroup) |

| Rucaparib (monotherapy) | TRITON2 (Phase II) | Fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, constipation | Anemia ≥ 3: ~25% |

| Talazoparib + Enzalutamide | TALAPRO-2 (Phase III) | Anemia, neutropenia, fatigue | Anemia most common grade 3–4 AE; neutropenia significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cicchetti, R.; Basconi, M.; Litterio, G.; Orsini, A.; Mascitti, M.; Digiacomo, A.; Salzano, G.; Tătaru, O.S.; Ferro, M.; Giulioni, C.; et al. Therapeutic Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Journey from Standard of Care to New Emerging Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311665

Cicchetti R, Basconi M, Litterio G, Orsini A, Mascitti M, Digiacomo A, Salzano G, Tătaru OS, Ferro M, Giulioni C, et al. Therapeutic Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Journey from Standard of Care to New Emerging Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311665

Chicago/Turabian StyleCicchetti, Rossella, Martina Basconi, Giulio Litterio, Angelo Orsini, Marco Mascitti, Alessio Digiacomo, Gaetano Salzano, Octavian Sabin Tătaru, Matteo Ferro, Carlo Giulioni, and et al. 2025. "Therapeutic Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Journey from Standard of Care to New Emerging Treatment" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311665

APA StyleCicchetti, R., Basconi, M., Litterio, G., Orsini, A., Mascitti, M., Digiacomo, A., Salzano, G., Tătaru, O. S., Ferro, M., Giulioni, C., Cafarelli, A., Schips, L., & Marchioni, M. (2025). Therapeutic Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Journey from Standard of Care to New Emerging Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311665