Improved HIV-1 Subtyping Accuracy Using near Full-Length Sequencing: A Comparison of Common Tools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Performance of NFL Sequencing

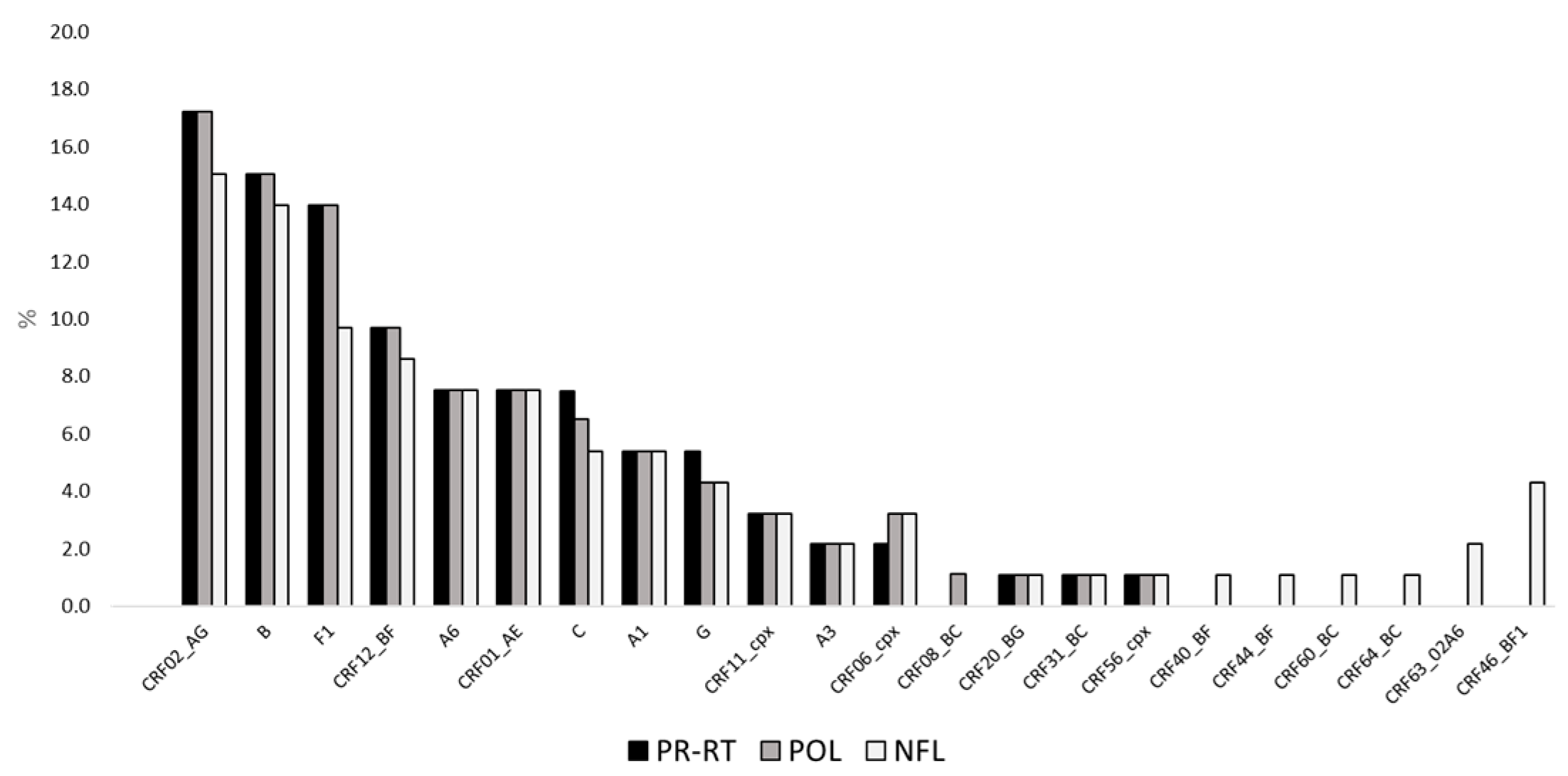

2.3. Subtype Prevalence According to Mphy Based on PR-RT, pol, and NFL Sequences

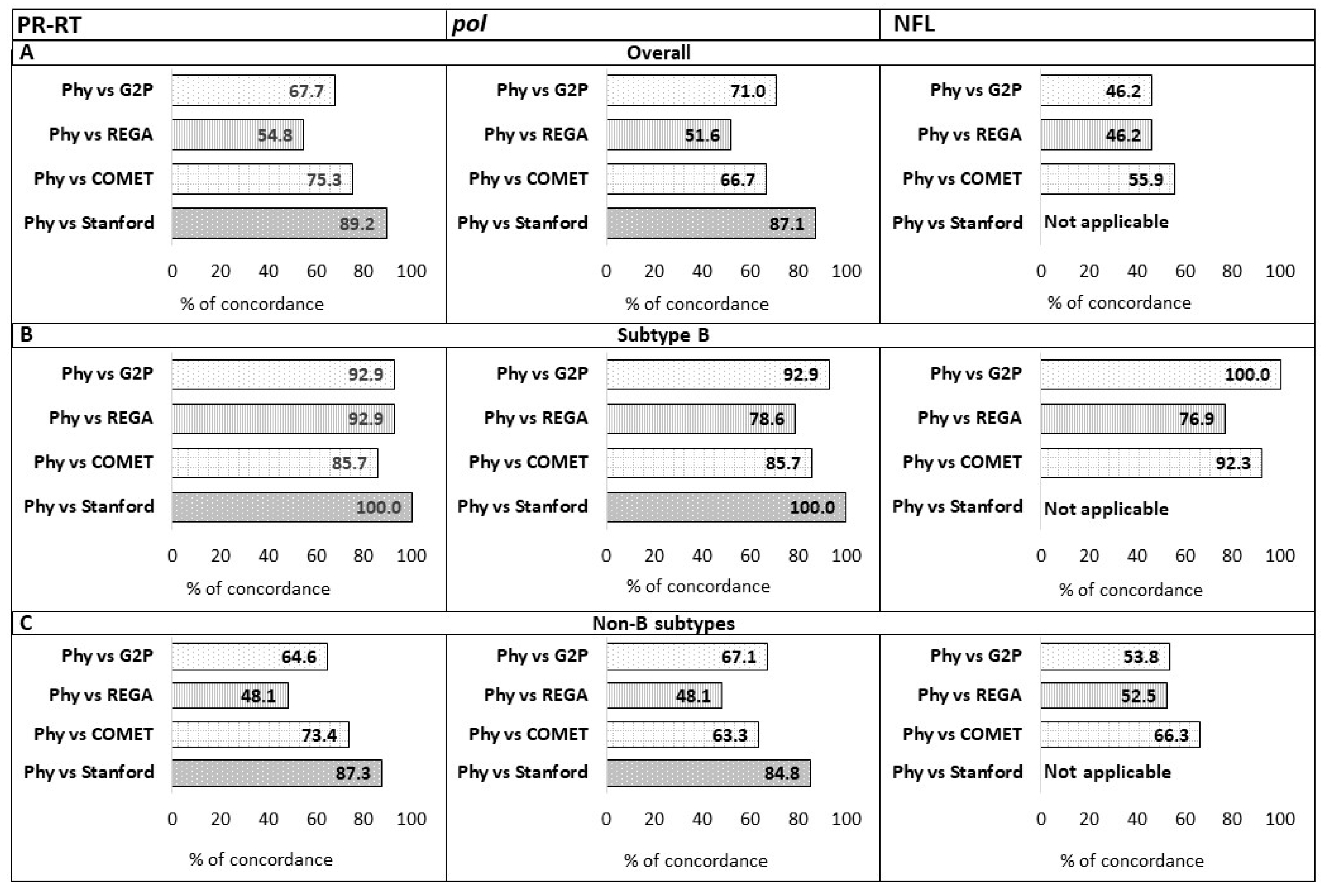

2.4. Concordance Between Automated Subtyping Tools and Mphy

2.5. Sensitivity and Specificity of Automated Subtyping Tools for Pure Subtype Assignment

2.6. Sensitivity and Specificity of Automated Subtyping Tools for CRF Assignment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population and Sample Collection

4.2. HIV-1 pol Next Generation Sequencing

4.3. HIV-1 NFL Next Generation Sequencing

4.4. HIV-1 Subtyping by Phylogenetic Analysis

4.5. HIV-1 Subtyping by Automated Online Tools

4.6. Standardization of Subtyping Tool Assignments

4.7. Concordance, Sensitivity, and Specificity

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robertson, D.L.; Anderson, J.P.; Bradac, J.A.; Carr, J.K.; Foley, B.; Funkhouser, R.K.; Gao, F.; Hahn, B.H.; Kalish, M.L.; Kuiken, C.; et al. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science 2000, 288, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemelaar, J.; Elangovan, R.; Yun, J.; Dickson-Tetteh, L.; Fleminger, I.; Kirtley, S.; Williams, B.; Gouws-Williams, E.; Ghys, P.D.; WHO–UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation Characterisation. Global and regional molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, 1990–2015: A systematic review, global survey, and trend analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 143–155, Erratum in Lancet Infect Dis. 2020, 20, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, S.; Bonhoeffer, S. Contribution of recombination to the evolutionary history of HIV. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2015, 10, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bbosa, N.; Kaleebu, P.; Ssemwanga, D. HIV subtype diversity worldwide. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2019, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.M.; Alteri, C.; Ronga, L.; Flandre, P.; Fabeni, L.; Mercurio, F.; D’Arrigo, R.; Gori, C.; Palamara, G.; Bertoli, A.; et al. Comparative analysis of drug resistance among B and the most prevalent non-B HIV type 1 subtypes (C, F, and CRF02_AG) in Italy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2012, 28, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloukas, A.; Psarris, A.; Giannelou, P.; Kostaki, E.; Hatzakis, A.; Paraskevis, D. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 infection in Europe: An overview. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 46, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabeni, L.; Alteri, C.; Berno, G.; Scutari, R.; Orchi, N.; De Carli, G.; Bertoli, A.; Carioti, L.; Gori, C.; Forbici, F.; et al. Characterisation of HIV-1 molecular transmission clusters among newly diagnosed individuals infected with non-B subtypes in Italy. Sex Transm. Infect. 2019, 95, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Menon, S.; Crowe, M.; Agarwal, N.; Biccler, J.; Bbosa, N.; Ssemwanga, D.; Adungo, F.; Moecklinghoff, C.; Macartney, M.; et al. Geographic and Population Distributions of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 Circulating Subtypes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis (2010–2021). J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Gettins, L.; Fuller, M.; Kirtley, S.; Hemelaar, J. Global and regional genetic diversity of HIV-1 in 2010-21: Systematic review and analysis of prevalence. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.M.; Perno, C.F. HIV-1 Genetic Variability and Clinical Implications. ISRN Microbiol. 2013, 2013, 481314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, N.; Laeyendecker, O.; Robb, M.; Kigozi, G.; Arroyo, M.; McCutchan, F.; Eller, L.A.; Eller, M.; Makumbi, F.; Birx, D.; et al. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 (HIV-1) subtype on disease progression in persons from Rakai, Uganda, with incident HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geretti, A.M.; Harrison, L.; Green, H.; Sabin, C.; Hill, T.; Fearnhill, E.; Pillay, D.; Dunn, D.; UK Collaborative Group on HIV Drug Resistance. Effect of HIV-1 subtype on virologic and immunologic response to starting highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Smith, M.; Mullen, J.; O’Shea, S.; Chrystie, I.; de Ruiter, A.; Tatt, I.D.; Geretti, A.M.; Zuckerman, M. Impact of HIV-1 viral subtype on disease progression and response to antiretroviral therapy. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2010, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwin, K.; Chaillon, A.; Scheibe, K.; Urbańska, A.; Aksak-Wąs, B.; Ząbek, P.; Siwak, E.; Cielniak, I.; Jabłonowska, E.; Wójcik-Cichy, K.; et al. Circulation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 A6 Variant in the Eastern Border of the European Union-Dynamics of the Virus Transmissions Between Poland and Ukraine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, A.; Lapovok, I.; Baryshev, P.; van de Vijver, D.A.M.C.; van Kampen, J.J.A.; Boucher, C.A.B.; Paraskevis, D.; Kireev, D. Genetic Features of HIV-1 Integrase Sub-Subtype A6 Predominant in Russia and Predicted Susceptibility to INSTIs. Viruses 2020, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrell, A.G.; Schapiro, J.M.; Perno, C.F.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Quercia, R.; Patel, P.; Polli, J.W.; Dorey, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Exploring predictors of HIV-1 virologic failure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine: A multivariable analysis. AIDS 2021, 35, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hué, S.; Clewley, J.P.; Cane, P.A.; Pillay, D. HIV-1 pol gene variation is sufficient for reconstruction of transmissions in the era of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2004, 18, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.M.; Fabeni, L.; Armenia, D.; Alteri, C.; Di Pinto, D.; Forbici, F.; Bertoli, A.; Di Carlo, D.; Gori, C.; Carta, S.; et al. Reliability and clinical relevance of the HIV-1 drug resistance test in patients with low viremia levels. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coldbeck-Shackley, R.C.; Adamson, P.J.; Whybrow, D.; Selway, C.A.; Papanicolas, L.E.; Turra, M.; Leong, L.E.X. Direct whole-genome sequencing of HIV-1 for clinical drug-resistance analysis and public health surveillance. J. Clin. Virol. 2024, 174, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Peña, A.C.; Faria, N.R.; Imbrechts, S.; Libin, P.; Abecasis, A.B.; Deforche, K.; Gómez-López, A.; Camacho, R.J.; de Oliveira, T.; Vandamme, A.M. Automated subtyping of HIV-1 genetic sequences for clinical and surveillance purposes: Performance evaluation of the new REGA version 3 and seven other tools. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013, 19, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.W.; Liu, T.F.; Shafer, R.W. The HIVdb system for HIV-1 genotypic resistance interpretation. Intervirology 2012, 55, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkl, M.; Büch, J.; Friedrich, G.; Böhm, M.; Turner, D.; Degen, O.; Kaiser, R.; Lengauer, T. Geno2pheno: Recombination detection for HIV-1 and HEV subtypes. NAR Mol. Med. 2024, 1, ugae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, D.; Lawyer, G.; Ternes, A.M.; Schmit, J.C.; Bercoff, D.P. COMET: Adaptive context-based modeling for ultrafast HIV-1 subtype identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topcu, C.; Georgiou, V.; Rodosthenous, J.H.; Kostrikis, L.G. Comparative HIV-1 Phylogenies Characterized by PR/RT, Pol and Near-Full-Length Genome Sequences. Viruses 2022, 14, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yebra, G.; de Mulder, M.; Martín, L.; Pérez-Cachafeiro, S.; Rodríguez, C.; Labarga, P.; García, F.; Tural, C.; Jaén, A.; Cohort of Spanish AIDS Research Network (CoRIS); et al. Sensitivity of seven HIV subtyping tools differs among subtypes/recombinants in the Spanish cohort of naïve HIV-infected patients (CoRIS). Antivir. Res. 2011, 89, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Posada, D.; Stawiski, E.; Chappey, C.; Poon, A.F.; Hughes, G.; Fearnhill, E.; Gravenor, M.B.; Leigh Brown, A.J.; Frost, S.D. An evolutionary model-based algorithm for accurate phylogenetic breakpoint mapping and subtype prediction in HIV-1. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banoo, S.; Bell, D.; Bossuyt, P.; Herring, A.; Mabey, D.; Poole, F.; Smith, P.G.; Sriram, N.; Wongsrichanalai, C.; Linke, R.; et al. Evaluation of diagnostic tests for infectious diseases: General principles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, S16–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabeni, L.; Berno, G.; Fokam, J.; Bertoli, A.; Alteri, C.; Gori, C.; Forbici, F.; Takou, D.; Vergori, A.; Zaccarelli, M.; et al. Comparative Evaluation of Subtyping Tools for Surveillance of Newly Emerging HIV-1 Strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2827–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y.; Kalish, M.L.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Shao, Y. Tracing the epidemic history of HIV-1 CRF01_AE clusters using near-complete genome sequences. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liang, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, D.; Liu, S.; et al. Genetic characterization of 13 subtype CRF01_AE near full-length genomes in Guangxi, China. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2010, 26, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwin, K.; Scheibe, K.; Urbańska, A.; Aksak-Wąs, B.; Karasińska-Cieślak, M.; Ząbek, P.; Siwak, E.; Cielniak, I.; Jabłonowska, E.; Wójcik-Cichy, K.; et al. Phylodynamic evolution of HIV-1 A6 sub-subtype epidemics in Poland. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, J.L.; St Clair, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Beloor, J.; Talarico, C.; Fridell, R.; Krystal, M.; White, C.T.; et al. Impact of Integrase Sequences from HIV-1 Subtypes A6/A1 on the In Vitro Potency of Cabotegravir or Rilpivirine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0170221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Cordwell, T.; Nguyen, H.; Li, J.; Jeffrey, J.L.; Kuritzkes, D.R. Effect of the L74I Polymorphism on Fitness of Cabotegravir-Resistant Variants of Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 Subtype A6. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpentier, C.; Storto, A.; Soulié, C.; Ferré, V.M.; Wirden, M.; Joly, V.; Lambert-Niclot, S.; Palich, R.; Morand-Joubert, L.; Landman, R.; et al. Prevalence of genotypic baseline risk factors for cabotegravir + rilpivirine failure among ARV-naive patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2983–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baryshev, P.B.; Bogachev, V.V.; Gashnikova, N.M. HIV-1 genetic diversity in Russia: CRF63_02A1, a new HIV type 1 genetic variant spreading in Siberia. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2014, 30, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivay, M.V.; Maksimenko, L.V.; Osipova, I.P.; Nefedova, A.A.; Gashnikova, M.P.; Zyryanova, D.P.; Ekushov, V.E.; Totmenin, A.V.; Nalimova, T.M.; Ivlev, V.V.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of HIV-1 CRF63_02A6 sub-epidemic. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 946787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, A.; Kireev, D.; Lapovok, I.; Shlykova, A.; Lopatukhin, A.; Pokrovskaya, A.; Bobkova, M.; Antonova, A.; Kuznetsova, A.; Ozhmegova, E.; et al. HIV-1 Drug Resistance among Treatment-Naïve Patients in Russia: Analysis of the National Database, 2006–2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousiappa, I.; Van De Vijver, D.A.; Kostrikis, L.G. Near full-length genetic analysis of HIV sequences derived from Cyprus: Evidence of a highly polyphyletic and evolving infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2009, 25, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunar, M.M.; Mlakar, J.; Zorec, T.M.; Poljak, M. HIV-1 Unique Recombinant Forms Identified in Slovenia and Their Characterization by Near Full-Length Genome Sequencing. Viruses 2020, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemey, P.; Salemi, M.; Vandamme, A.M. (Eds.) The Phylogenetic Handbook: A Practical Approach to Phylogenetic Analysis and Hypothesis Testing, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; de Oliveira, T.; Rambaut, A.; Myers, R.E.; Gale, C.V.; Dunn, D.; Shafer, R.; Vandamme, A.M.; Kellam, P.; Pillay, D.; et al. Assessment of automated genotyping protocols as tools for surveillance of HIV-1 genetic diversity. AIDS 2006, 20, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín, A.; López, M.; Soriano, V. Reliability of rapid subtyping tools compared to that of phylogenetic analysis for characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 non-B subtypes and recombinant forms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 3896–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyne, M.T.; Simmon, K.E.; Mallory, M.A.; Hymas, W.C.; Stevenson, J.; Barker, A.P.; Hillyard, D.R. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Assay Using Ion Torrent Next Generation Sequencing and On-Instrument End-to-End Analysis Software. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0025322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mphy | ||

|---|---|---|

| PR-RT | pol | NFL |

| B | B | CRF40_BF1 |

| C | C | CRF31_BC |

| C | CRF08_BC | CRF64_BC |

| CRF02_AG | CRF06_cpx | CRF06_cpx |

| CRF02_AG | CRF02_AG | CRF63_02A6 |

| CRF02_AG | CRF02_AG | CRF63_02A6 |

| CRF12_BF | CRF12_BF | CRF44_BF1 |

| CRF31_BC | CRF31_BC | CRF60_BC |

| F1 | F1 | CRF46_BF1 |

| F1 | F1 | CRF46_BF1 |

| F1 | F1 | CRF46_BF1 |

| F1 | F1 | CRF46_BF1 |

| G | CRF02_AG | CRF02_AG |

| Subtype or CRF | N Mphy | % SENSITIVITY (95% CI a) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford v9.8 | COMET v2.4 | REGA v3.0 | Geno2Pheno v3.5 | ||||||||||||

| PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | |

| B | 14 | 14 | 13 | 100.0 (79.0–100.0) | 100.0 (79.0–100.0) | 85.7 (63.5–92.5) | 85.7 (63.5–92.5) | 92.3 (71.0–92.3) | 92.9 (70.4–99.6) | 78.6 (57.6–78.6) | 76.9 (54.6–76.9) | 92.9 (69.7–99.6) | 92.9 (72.9–92.9) | 100.0 (80.1–100.0) | |

| A1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 100.0 (55.2–100.0) | 100.0 (55.2–100.0) | 100.0 (49.1–100.0) | 80.0 (34.3–98.2) | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | 100.0 (48.9–100.0) | 80.0 (31.5–98.9) | 100.0 (48.9–100.0) | 100.0 (55.2–100.0) | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | |

| A6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | NA | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |||

| C | 7 | 6 | 5 | 100.0 (63.5–100.0) | 100.0 (57.5–100.0) | 100.0 (63.5–100.0) | 100.0 (57.5–100.0) | 100.0(51.5–100.0) | 85.7 (50.4–85.7) | 100.0 (57.5–100.0) | 100.0 (51.5–100.0) | 100.0 (63.5–100.0) | 100.0 (57.5–100.0) | 100.0 (50.7–100.0) | |

| G | 5 | 4 | 4 | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | 100.0 (43.9–100.0) | NA | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | 100.0 (47.3–100.0) | 25.0 (1.4–25.0) | 80.0 (36.1–80.0) | 100.0 (47.3–100.0) | 75.0 (26.2–75.0) | 80.0 (33.3–98.9) | 100.0 (43.2–100.0) | 100.0 (47.3–100.0) |

| F1 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 100.0 (80.1–100.0) | 100.0 (80.1–100.0) | 84.6 (62.6–84.6) | 61.5 (39.5–61.5) | 55.6 (27.8–55.6) | 92.3 (71.0–92.3) | 100.0 (80.1–100.0) | 88.9(54.2–99.4) | 92.3 (71.0–92.3) | 84.6 (62.6–84.6) | 44.4 (18.8–44.4) | |

| CRF01_AE | 7 | 7 | 7 | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 85.7 (50.4–85.7) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | 100.0 (65.7–100.0) | |

| CRF02_AG | 16 | 16 | 14 | 100.0 (82.3–100.0) | 100.0 (82.3–100.0) | 50.0 (30.4–55.9) | 62.5 (43.5–62.5) | 64.3 (43.3–64.3) | 6.3 (0.3–12.2) | 18.8 (6.0–18.8) | 28.6 (11.2–35.3) | 43.8 (24.8–49.7) | 75.0 (56.0–75.0) | 28.6 (11.2–35.3) | |

| CRF12_BF | 9 | 9 | 8 | 55.6 (27.8–55.6) | 55.6 (27.8–55.6) | 55.6 (27.8–55.6) | 33.3 (10.9–33.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 11.1 (0.6–11.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | NA | |||

| Subtype or CRF | N Mphy | % SPECIFICITY (95% CI a) | |||||||||||||

| Stanford v9.8 | COMET v2.4 | REGA v3.0 | Geno2Pheno v3.5 | ||||||||||||

| PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | PR-RT | pol | NFL | |

| B | 14 | 14 | 13 | 97.5 (93.8–97.5) | 98.7 (95.2–98.7) | 98.7 (94.8–99.9) | 98.7 (94.8–99.9) | 100.0 (96.5–100.0) | 97.5 (93.5–98.7) | 100.0 (96.3–100.0) | 100.0 (96.4–100.0) | 96.2 (92.1–97.4) | 100.0 (96.5–100.0) | 100.0 (96.8–100.0) | |

| A1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 92.0 (89.2–92.0) | 98.9 (96.3–99.9) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 90.9 (88.0–90.9) | 90.9 (88.2–92.0) | 90.9 (88.0–90.9) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | |

| A6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | NA | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (100.0–100.0) | |||

| C | 7 | 6 | 5 | 98.8 (95.9–98.8) | 97.7 (94.8–97.7) | 98.8 (95.9–98.8) | 97.7 (94.8–97.7) | 97.7 (95.0–97.7) | 100.0 (97.1–100.0) | 97.7 (94.8–97.7) | 97.7 (95.0–97.7) | 98.8 (95.9–98.8) | 97.7 (94.8–97.7) | 96.6 (93.8–96.6) | |

| G | 5 | 4 | 4 | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 97.8 (95.2–97.8) | NA | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 100.0 (97.6–100.0) | 100.0 (98.9–100.0) | 100.0 (97.5–100.0) | 100.0 (97.6–100.0) | 100.0 (97.8–100.0) | 97.7 (95.1–98.8) | 96.6 (94.1–96.6) | 100.0 (97.6–100.0) |

| F1 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 100.0 (96.8–100.0) | 100.0 (96.8–100.0) | 100.0 (96.4–100.0) | 100.0 (96.4–100.0) | 100.0 (97.0–100.0) | 100.0 (96.5–100.0) | 100.0 (96.8–100.0) | 91.7 (88.0–92.8) | 100.0 (96.5–100.0) | 100.0 (96.4–100.0) | 100.0 (97.3–100.0) | |

| CRF01_AE | 7 | 7 | 7 | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.1–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | 100.0 (97.2–100.0) | |

| CRF02_AG | 16 | 16 | 14 | 98.7 (95.0–98.7) | 98.7 (95.0–98.7) | 98.7 (94.6–99.9) | 100.0 (96.1–100.0) | 100.0 (96.3–100.0) | 98.7 (97.5–99.9) | 100.0 (97.3–100.0) | 98.7 (95.6–99.9) | 98.7 (94.8–99.9) | 100.0 (96.1–100.0) | 98.7 (95.6–99.9) | |

| CRF12_BF | 9 | 9 | 8 | 100.0 (97.0–100.0) | 100.0 (97.0–100.0) | 100.0 (97.0–100.0) | 100.0 (97.6–100.0) | 100.0 (100.0–100.0) | 100.0 (98.9–100.0) | 100.0 (100.0–100.0) | 100.0 (100.0–100.0) | NA | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smoquina, F.; Berno, G.; Forbici, F.; Sberna, G.; Rozera, G.; Abbate, I.; Lazzari, E.; Amendola, A.; Mazzotta, V.; Gagliardini, R.; et al. Improved HIV-1 Subtyping Accuracy Using near Full-Length Sequencing: A Comparison of Common Tools. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311666

Smoquina F, Berno G, Forbici F, Sberna G, Rozera G, Abbate I, Lazzari E, Amendola A, Mazzotta V, Gagliardini R, et al. Improved HIV-1 Subtyping Accuracy Using near Full-Length Sequencing: A Comparison of Common Tools. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311666

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmoquina, Flavia, Giulia Berno, Federica Forbici, Giuseppe Sberna, Gabriella Rozera, Isabella Abbate, Elisabetta Lazzari, Alessandra Amendola, Valentina Mazzotta, Roberta Gagliardini, and et al. 2025. "Improved HIV-1 Subtyping Accuracy Using near Full-Length Sequencing: A Comparison of Common Tools" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311666

APA StyleSmoquina, F., Berno, G., Forbici, F., Sberna, G., Rozera, G., Abbate, I., Lazzari, E., Amendola, A., Mazzotta, V., Gagliardini, R., Antinori, A., Girardi, E., Maggi, F., & Fabeni, L. (2025). Improved HIV-1 Subtyping Accuracy Using near Full-Length Sequencing: A Comparison of Common Tools. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311666