Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming to Combination Therapy Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

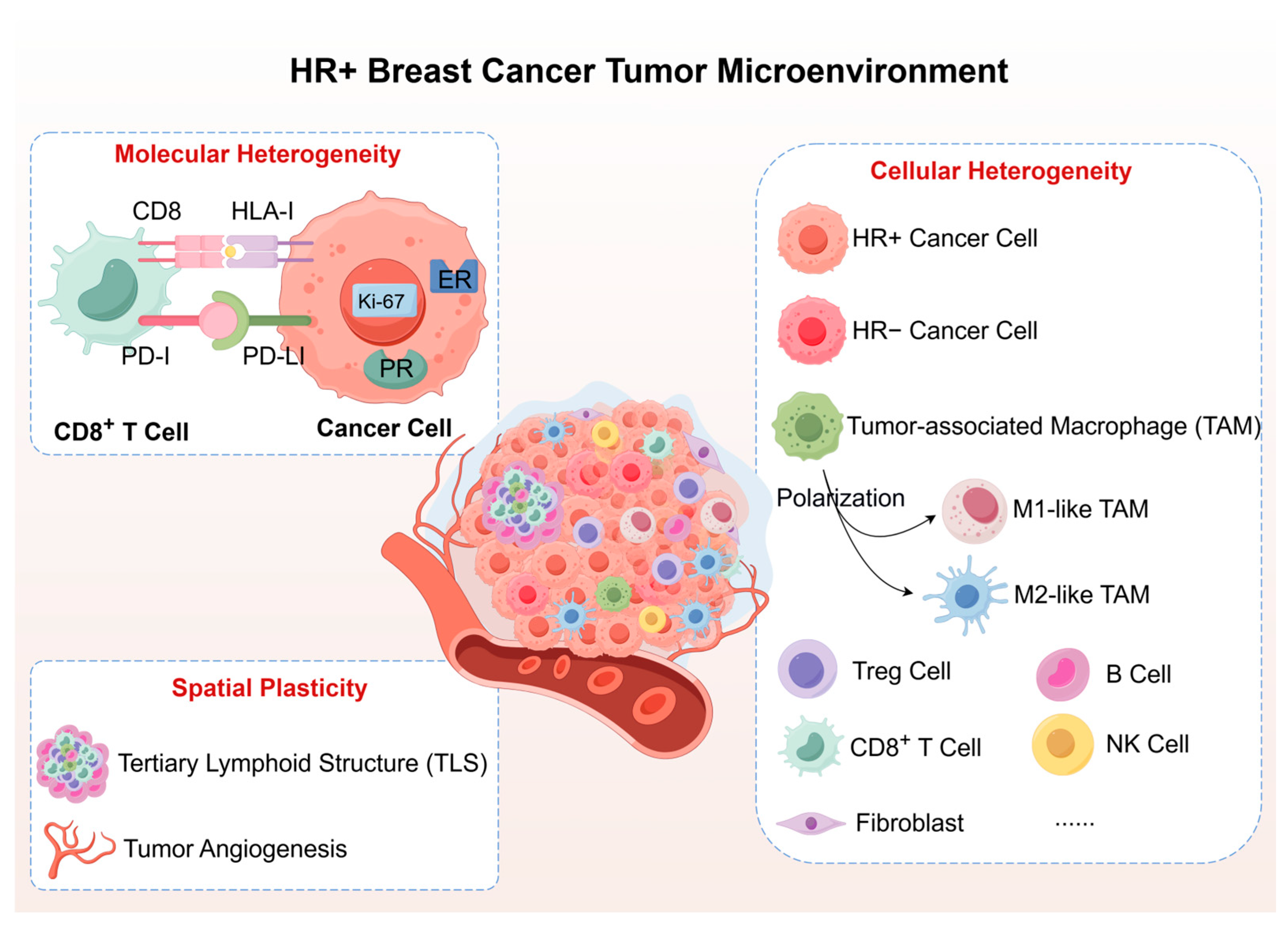

2. Tumor Microenvironment Heterogeneity and Plasticity in HR+ Breast Cancer: The Static Foundation

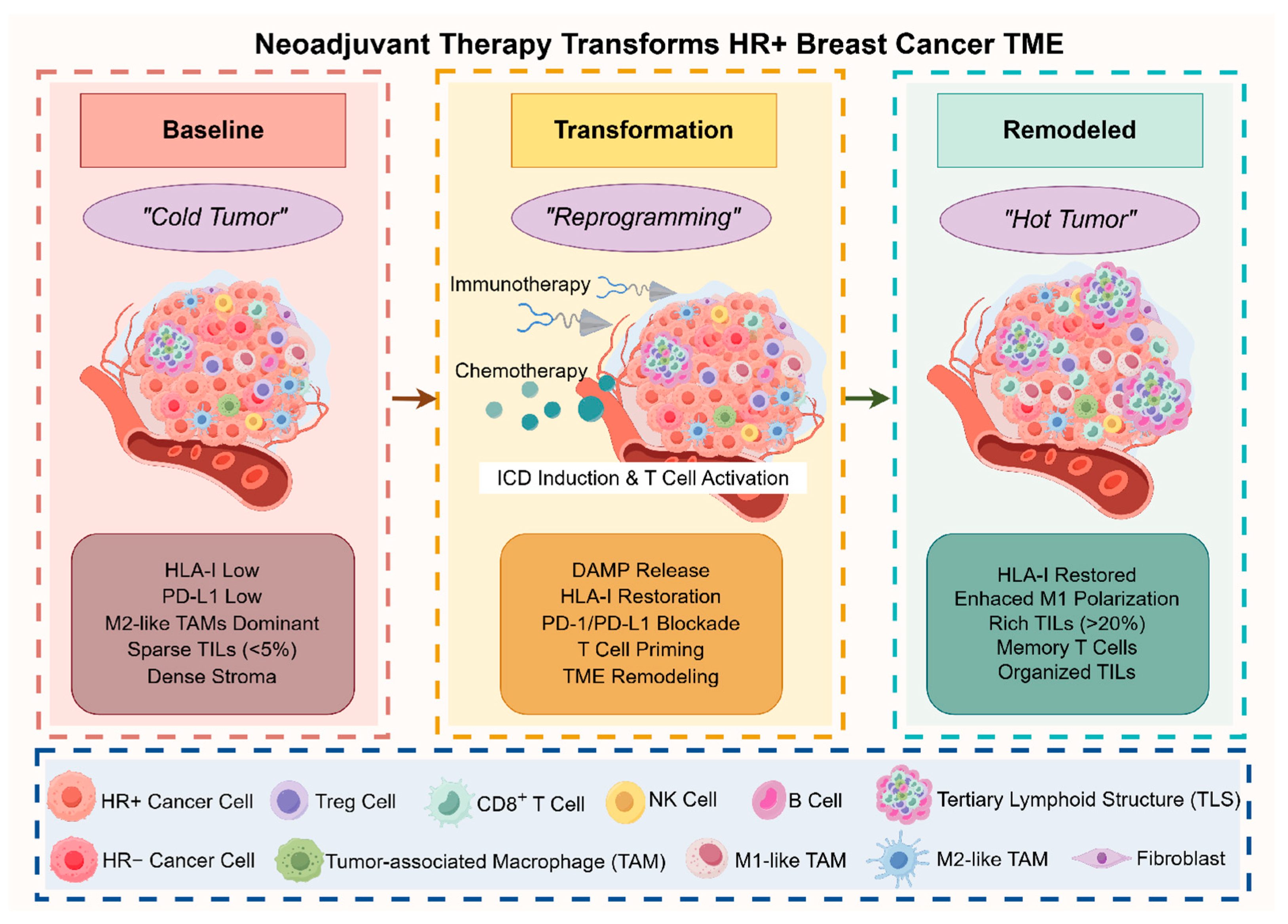

3. Dynamic TME Reprogramming: Mechanistic Insights into Immunotherapy Response

3.1. Chemotherapy-Induced Immunogenic Transformation

3.1.1. Agent-Specific ICD Cascades in HR+ Breast Cancer

3.1.2. Enhanced Antigen Processing and Presentation

3.1.3. Immune Cell Recruitment and TME Priming

3.2. Checkpoint Blockade-Mediated Immune Amplification

3.2.1. PD-1/PD-L1 Axis Disruption and T Cell Liberation

3.2.2. Reversal of Immunosuppressive Networks

3.2.3. Mechanisms of Immune Desert-to-Inflamed Conversion

4. Precision Biomarker Strategies: Patient Selection and Treatment Monitoring

4.1. Baseline Biomarkers for Patient Selection

4.1.1. PD-L1 Expression: Assay Selection and Clinical Implementation

4.1.2. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Immune Architecture

4.1.3. HLA Class I Status and Restoration Potential

4.1.4. Integrated Biomarker Algorithms for Patient Stratification

4.2. Dynamic Monitoring During Neoadjuvant Treatment

4.3. Treatment Decision Algorithms

4.3.1. Baseline Risk-Stratified Treatment Selection

4.3.2. Response-Adaptive Treatment Modification

5. Combination Therapy Strategies: From Clinical Evidence to Practice

5.1. Phase III Evidence: Validated Combinations

5.1.1. HR+ Disease: Biomarker-Driven Success

5.1.2. TNBC Standard as Reference

5.1.3. Clinical Implementation Framework

5.2. Phase II Signals: Promising Approaches

5.2.1. PARP Inhibitor Combinations

5.2.2. Antibody–Drug Conjugate Immunotherapy Combinations

5.3. Failed Strategies: Lessons for Future Development

5.3.1. CDK4/6 Inhibitor Combinations

5.3.2. Other Instructive Failures

6. Clinical Translation and Future Directions

6.1. Development Innovations

6.2. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | apparent diffusion coefficient |

| AI | aromatase inhibitor |

| CCL2 | CC-chemokine ligand 2 |

| CDK4/6 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 |

| cGAS-STING | cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes |

| CPS | Combined Positive Score |

| CSF-1 | colony-stimulating factor 1 |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| CTLA-4 | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| DOP | durvalumab-olaparib-paclitaxel |

| EFS | event-free survival |

| ER | estrogen receptor |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| HMGB1 | high mobility group box 1 |

| HR+ | hormone receptor-positive |

| HRD | homologous recombination deficiency |

| ICAM-1 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| ICD | immunogenic cell death |

| ICIs | immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IDO1 | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| IFN-β | interferon-β |

| IFN-γ | interferon-γ |

| LAG-3 | lymphocyte activation gene 3 |

| MDSC | myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinases |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| ORR | objective response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

| pCR | pathological complete response |

| PD-L1 | programmed cell death ligand 1 |

| RCB | residual cancer burden |

| STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 |

| TAMs | tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCF1 | T cell factor 1 |

| TIGIT | T cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains |

| TIL | tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte |

| TIM-3 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 |

| TMB | tumor mutational burden |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC | triple-negative breast cancer |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, H.J.; Temin, S.; Anderson, H.; Buchholz, T.A.; Davidson, N.E.; Gelmon, K.E.; Giordano, S.H.; Hudis, C.A.; Rowden, D.; Solky, A.J.; et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2255–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Philips, A.V.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Qiao, N.; Wu, Y.; Harrington, S.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Akcakanat, A.; et al. PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luen, S.; Virassamy, B.; Savas, P.; Salgado, R.; Loi, S. The genomic landscape of breast cancer and its interaction with host immunity. Breast 2016, 29, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkert, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Lederer, B.; Heppner, B.I.; Weber, K.E.; Budczies, J.; Huober, J.; Klauschen, F.; Furlanetto, J.; et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: A pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Salgado, R.; Curigliano, G.; Romero Díaz, R.I.; Delaloge, S.; Rojas García, C.I.; Kok, M.; Saura, C.; Harbeck, N.; Mittendorf, E.A.; et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab and chemotherapy in early estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Liu, Z.; McArthur, H.; Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Harbeck, N.; Telli, M.L.; Cescon, D.W.; Fasching, P.A.; et al. Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in high-risk, early-stage, ER(+)/HER2(-) breast cancer: A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, L.A.; Somerfield, M.R.; Carey, L.A.; Crews, J.R.; Denduluri, N.; Hwang, E.S.; Khan, S.A.; Loibl, S.; Morris, E.A.; Perez, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Endocrine Therapy, and Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1485–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiei, S.; Simons, J.M.; Engelen, S.M.E.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Classe, J.M.; Smidt, M.L. Axillary Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy by Breast Cancer Subtype in Patients With Initially Clinically Node-Positive Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, e210891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Meng, X.; Yang, H.; Dong, H. Advances in technology and applications of nanoimmunotherapy for cancer. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Manspeaker, M.P.; Thomas, S.N. Augmenting the synergies of chemotherapy and immunotherapy through drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2019, 88, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; O’Donnell, J.S.; Yan, J.; Madore, J.; Allen, S.; Smyth, M.J.; Teng, M.W.L. Timing of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in relation to surgery is crucial for outcome. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1581530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Blake, S.J.; Yong, M.C.; Harjunpää, H.; Ngiow, S.F.; Takeda, K.; Young, A.; O’Donnell, J.S.; Allen, S.; Smyth, M.J.; et al. Improved Efficacy of Neoadjuvant Compared to Adjuvant Immunotherapy to Eradicate Metastatic Disease. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.X.; Haebe, S.; Lee, A.S.; Westphalen, C.B.; Norton, J.A.; Jiang, W.; Levy, R. Intratumoral Immunotherapy for Early-stage Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 3091–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Shima, H.; Kutomi, G.; Kyuno, D.; Wada, A.; Kuga, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Hirohashi, Y.; Torigoe, T.; Takemasa, I. Prognostic Impact of Human Lymphocyte Antigen (HLA) Class I Expression in Patients With Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2024, 44, 4039–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torigoe, T.; Asanuma, H.; Nakazawa, E.; Tamura, Y.; Hirohashi, Y.; Yamamoto, E.; Kanaseki, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Sato, N. Establishment of a monoclonal anti-pan HLA class I antibody suitable for immunostaining of formalin-fixed tissue: Unusually high frequency of down-regulation in breast cancer tissues. Pathol. Int. 2012, 62, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, P.; Shin, E.C.; Perosa, F.; Vacca, A.; Dammacco, F.; Racanelli, V. MHC class I antigen processing and presenting machinery: Organization, function, and defects in tumor cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascierto, M.L.; Kmieciak, M.; Idowu, M.O.; Manjili, R.; Zhao, Y.; Grimes, M.; Dumur, C.; Wang, E.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Wang, X.Y.; et al. A signature of immune function genes associated with recurrence-free survival in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 131, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, M.L.; Sparbier, C.E.; Chan, Y.C.; Williamson, J.C.; Woods, K.; Beavis, P.A.; Lam, E.Y.N.; Henderson, M.A.; Bell, C.C.; Stolzenburg, S.; et al. CMTM6 maintains the expression of PD-L1 and regulates anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2017, 549, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Xu, S.; Rosemblit, C.; Smith, J.B.; Cintolo, J.A.; Powell, D.J., Jr.; Czerniecki, B.J. CD4(+) T-Helper Type 1 Cytokines and Trastuzumab Facilitate CD8(+) T-cell Targeting of HER2/neu-Expressing Cancers. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenfeld, L.; Xu, S.; Czerniecki, B.J. CD4(+) Th1 to the rescue in HER-2+ breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1078062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, M.A.; Rodriguez, T.; Zinchenko, S.; Maleno, I.; Ruiz-Cabello, F.; Concha, Á.; Olea, N.; Garrido, F.; Aptsiauri, N. HLA class I alterations in breast carcinoma are associated with a high frequency of the loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 6 and 15. Immunogenetics 2018, 70, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, M.A.; Navarro-Ocón, A.; Ronco-Díaz, V.; Olea, N.; Aptsiauri, N. Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH) Affecting HLA Genes in Breast Cancer: Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Opportunities. Genes 2024, 15, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.G.; Cha, Y.J.; Bae, S.J.; Yoon, C.; Lee, H.W.; Jeong, J. Comparisons of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte levels and the 21-gene recurrence score in ER-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griguolo, G.; Dieci, M.V.; Paré, L.; Miglietta, F.; Generali, D.G.; Frassoldati, A.; Cavanna, L.; Bisagni, G.; Piacentini, F.; Tagliafico, E.; et al. Immune microenvironment and intrinsic subtyping in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Quiceno, D.G.; Zabaleta, J.; Ortiz, B.; Zea, A.H.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Delgado, A.; Correa, P.; Brayer, J.; Sotomayor, E.M.; et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5839–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, A.L.; Munn, D.H. Tryptophan catabolism and regulation of adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 5809–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Demaria, S.; Sirtaine, N.; Klauschen, F.; Pruneri, G.; Wienert, S.; Van den Eynden, G.; Baehner, F.L.; Penault-Llorca, F.; et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: Recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmink, B.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Basar, R.; Thakur, R.; Yizhak, K.; Sade-Feldman, M.; Blando, J.; Han, G.; et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature 2020, 577, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautès-Fridman, C.; Petitprez, F.; Calderaro, J.; Fridman, W.H. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Skaarup Larsen, M.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565, Erratum in Nature 2020, 580, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieci, M.V.; Miglietta, F.; Guarneri, V. Immune Infiltrates in Breast Cancer: Recent Updates and Clinical Implications. Cells 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, I.A.; Song, I.H.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Yu, J.H.; Gong, G. Tertiary lymphoid structures: Prognostic significance and relationship with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 69, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Tumor Immunology and Tumor Evolution: Intertwined Histories. Immunity 2020, 52, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.R.; Glont, S.E.; Blows, F.M.; Provenzano, E.; Dawson, S.J.; Liu, B.; Hiller, L.; Dunn, J.; Poole, C.J.; Bowden, S.; et al. PD-L1 protein expression in breast cancer is rare, enriched in basal-like tumours and associated with infiltrating lymphocytes. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalper, K.A.; Velcheti, V.; Carvajal, D.; Wimberly, H.; Brown, J.; Pusztai, L.; Rimm, D.L. In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimberly, H.; Brown, J.R.; Schalper, K.; Haack, H.; Silver, M.R.; Nixon, C.; Bossuyt, V.; Pusztai, L.; Lannin, D.R.; Rimm, D.L. PD-L1 Expression Correlates with Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisseret, L.; Garaud, S.; de Wind, A.; Van den Eynden, G.; Boisson, A.; Solinas, C.; Gu-Trantien, C.; Naveaux, C.; Lodewyckx, J.N.; Duvillier, H.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition, organization and PD-1/PD-L1 expression are linked in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1257452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, U.; Wetherilt, C.S.; Yang, J.; Peng, L.; Li, X. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are significantly associated with better overall survival and disease-free survival in triple-negative but not estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 64, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S. Dysregulated tumor-associated macrophages in carcinogenesis, progression and targeted therapy of gynecological and breast cancers. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cho, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Lau, A.W.; Laird, M.S.; Brown, D.; McAuliffe, P.; Lee, A.V.; Oesterreich, S.; et al. Cancer-cell derived S100A11 promotes macrophage recruitment in ER+ breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2429186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Zhou, T.; Shi, H.; Yao, M.; Zhang, D.; Qian, H.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jin, F.; Chai, C.; et al. Progranulin induces immune escape in breast cancer via up-regulating PD-L1 expression on tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and promoting CD8(+) T cell exclusion. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2021, 40, 4, Erratum in J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Ruan, L.; Huang, M.; Chen, W.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z. Integrated single-cell and bulk transcriptomic analysis identifies a novel macrophage subtype associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Ji, H.; Niu, X.; Yin, L.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q. Tumor-associated macrophages secrete CC-chemokine ligand 2 and induce tamoxifen resistance by activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, S.; Abrahamsson, A.; Rodriguez, G.V.; Olsson, A.K.; Jensen, L.; Cao, Y.; Dabrosin, C. CCL2 and CCL5 Are Novel Therapeutic Targets for Estrogen-Dependent Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3794–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Tsang, J.Y.; Tse, G.M. Tumor Microenvironment in Breast Cancer—Updates on Therapeutic Implications and Pathologic Assessment. Cancers 2021, 13, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsipe, T.; Mohamedelhassan, R.; Akinpelu, A.; Pondugula, S.R.; Mistriotis, P.; Avila, L.A.; Suryawanshi, A. Cellular interactions in tumor microenvironment during breast cancer progression: New frontiers and implications for novel therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1302587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bejarano, O.H.; Parra-López, C.; Patarroyo, M.A. A review concerning the breast cancer-related tumour microenvironment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 199, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Hoyo, A.; Cobain, E.; Huppert, L.A.; Beitsch, P.D.; Buchholz, T.A.; Esserman, L.; van‘t Veer, L.J.; Rugo, H.S.; Pusztai, L. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy for Estrogen Receptor-Positive Human Epidermal Growth Factor 2-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2632–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C.; Martin, F.; Apetoh, L.; Bouyer, F.; Ghiringhelli, F. Cancer chemotherapy: Not only a direct cytotoxic effect, but also an adjuvant for antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2008, 57, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacampa, G.; Navarro, V.; Matikas, A.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Schettini, F.; Tolosa, P.; Martínez-Sáez, O.; Sánchez-Bayona, R.; Ferrero-Cafiero, J.M.; Salvador, F.; et al. Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Plus Chemotherapy in Early Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysko, D.V.; Garg, A.D.; Kaczmarek, A.; Krysko, O.; Agostinis, P.; Vandenabeele, P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Hollebecque, A.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. PD-1 blockade synergizes with oxaliplatin-based, but not cisplatin-based, chemotherapy of gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2093518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacchelli, E.; Aranda, F.; Eggermont, A.; Galon, J.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Cremer, I.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Trial Watch: Chemotherapy with immunogenic cell death inducers. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e27878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Ju, X.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Ren, M.; Zhang, H. Immunogenic cell death in anticancer chemotherapy and its impact on clinical studies. Cancer Lett. 2018, 438, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, B.; Qiao, X.; Janssen, L.; Velds, A.; Groothuis, T.; Kerkhoven, R.; Nieuwland, M.; Ovaa, H.; Rottenberg, S.; van Tellingen, O.; et al. Drug-induced histone eviction from open chromatin contributes to the chemotherapeutic effects of doxorubicin. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaretakis, T.; Kepp, O.; Brockmeier, U.; Tesniere, A.; Bjorklund, A.C.; Chapman, D.C.; Durchschlag, M.; Joza, N.; Pierron, G.; van Endert, P.; et al. Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.; Tesniere, A.; Kepp, O.; Michaud, M.; Schlemmer, F.; Senovilla, L.; Séror, C.; Métivier, D.; Perfettini, J.L.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. Chemotherapy induces ATP release from tumor cells. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3723–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.; Tesniere, A.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Fimia, G.M.; Apetoh, L.; Perfettini, J.L.; Castedo, M.; Mignot, G.; Panaretakis, T.; Casares, N.; et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Tesniere, A.; Criollo, A.; Ortiz, C.; Lidereau, R.; Mariette, C.; Chaput, N.; Mira, J.P.; Delaloge, S.; et al. The interaction between HMGB1 and TLR4 dictates the outcome of anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2007, 220, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchelli, E.; Ma, Y.; Baracco, E.E.; Sistigu, A.; Enot, D.P.; Pietrocola, F.; Yang, H.; Adjemian, S.; Chaba, K.; Semeraro, M.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced antitumor immunity requires formyl peptide receptor 1. Science 2015, 350, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, T.S.; Chan, L.K.Y.; Man, G.C.W.; Wong, C.H.; Lee, J.H.S.; Yim, S.F.; Cheung, T.H.; McNeish, I.A.; Kwong, J. Paclitaxel Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Ovarian Cancer via TLR4/IKK2/SNARE-Dependent Exocytosis. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Qu, Y.; Guo, B.; Zheng, H.; Meng, F.; Zhong, Z. Micellar paclitaxel boosts ICD and chemo-immunotherapy of metastatic triple negative breast cancer. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Yang, H.; Ye, Z.; Gao, B.; Qian, Z.; Ding, Y.; Mao, Z.; Du, Y.; Wang, W. Celecoxib Augments Paclitaxel-Induced Immunogenic Cell Death in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 15864–15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, L.; Guo, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, X. Self-assembly of paclitaxel derivative and fructose as a potent inducer of immunogenic cell death to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavoni, G.; Sistigu, A.; Valentini, M.; Mattei, F.; Sestili, P.; Spadaro, F.; Sanchez, M.; Lorenzi, S.; D’Urso, M.T.; Belardelli, F.; et al. Cyclophosphamide synergizes with type I interferons through systemic dendritic cell reactivation and induction of immunogenic tumor apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernis, A.B. Estrogen and CD4+ T cells. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2007, 19, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Waxman, D.J. Medium dose intermittent cyclophosphamide induces immunogenic cell death and cancer cell autonomous type I interferon production in glioma models. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Waxman, D.J. Metronomic cyclophosphamide eradicates large implanted GL261 gliomas by activating antitumor Cd8(+) T-cell responses and immune memory. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e1005521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shi, G.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, X.; Jiang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Nanomicelle protects the immune activation effects of Paclitaxel and sensitizes tumors to anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8382–8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Chang, Z.; Li, T.; et al. Coordination and Redox Dual-Responsive Mesoporous Organosilica Nanoparticles Amplify Immunogenic Cell Death for Cancer Chemoimmunotherapy. Small 2021, 17, e2100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn, B.V.; Weber, K.E.; Schmitt, W.D.; Fasching, P.A.; Symmans, W.F.; Blohmer, J.U.; Karn, T.; Taube, E.T.; Klauschen, F.; Marmé, F.; et al. Human leucocyte antigen class I in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer: Association with response and survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2019, 21, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.W.; Marshall, E.A.; Bell, J.C.; Lam, W.L. cGAS-STING and Cancer: Dichotomous Roles in Tumor Immunity and Development. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.H.; Kim, Y.A.; Heo, S.H.; Bang, W.S.; Park, H.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, H.; Seo, J.H.; Cho, Y.; Jung, S.W.; et al. The Association of Estrogen Receptor Activity, Interferon Signaling, and MHC Class I Expression in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 54, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, Z.; Dong, L.; Cao, H.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. DNA damage response in breast cancer and its significant role in guiding novel precise therapies. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Pacífico, J.P.; Sammons, S.; Tolaney, S.M. Tumor Mutational Burden in Breast Cancer: Current Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities. Cancers 2023, 15, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Park, I.; Han, B.; Baek, Y.; Moon, D.; Jeon, N.L.; Doh, J. Cytotoxic chemotherapy in a 3D microfluidic device induces dendritic cell recruitment and trogocytosis of cancer cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blander, J.M. Phagocytosis and antigen presentation: A partnership initiated by Toll-like receptors. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67 (Suppl. 3), iii44–iii49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoteau, A.; Henin, C.; Svec, D.; Bisilliat Donnet, C.; Denanglaire, S.; Colau, D.; Romero, P.; Leo, O.; Van den Eynde, B.; Moser, M. Cyclophosphamide treatment regulates the balance of functional/exhausted tumor-specific CD8(+) T cells. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1318234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, K.; Salvagno, C.; de Visser, K.E. Exploiting the Immunomodulatory Properties of Chemotherapeutic Drugs to Improve the Success of Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, I.G.; Savas, P.; Lai, J.; Chen, A.X.Y.; Oliver, A.J.; Teo, Z.L.; Todd, K.L.; Henderson, M.A.; Giuffrida, L.; Petley, E.V.; et al. Macrophage-Derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 Are Required for Antitumor Immune Responses Following Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y. Tertiary lymphoid structures achieve ‘cold’ to ‘hot’ transition by remodeling the cold tumor microenvironment. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imani, S.; Farghadani, R.; Roozitalab, G.; Maghsoudloo, M.; Emadi, M.; Moradi, A.; Abedi, B.; Jabbarzadeh Kaboli, P. Reprogramming the breast tumor immune microenvironment: Cold-to-hot transition for enhanced immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2025, 44, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y. Improvement of the anticancer efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade via combination therapy and PD-L1 regulation. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, J.; Peng, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, D.; He, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B. Tumor microenvironment: Nurturing cancer cells for immunoevasion and druggable vulnerabilities for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2024, 611, 217385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalian, S.L.; Drake, C.G.; Pardoll, D.M. Immune checkpoint blockade: A common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Impact of oncogenic pathways on evasion of antitumour immune responses. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, V.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; Melino, G.; Amelio, I. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, E.A.; Gru, A.A.; Atkins, K.A.; Friedman, L.A.; Moore, M.E.; Bullock, T.N.; Cross, J.V.; Dillon, P.M.; Mills, A.M. PD-L1 Expression and Intratumoral Heterogeneity Across Breast Cancer Subtypes and Stages: An Assessment of 245 Primary and 40 Metastatic Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhao, W.; Yan, C.; Watson, C.C.; Massengill, M.; Xie, M.; Massengill, C.; Noyes, D.R.; Martinez, G.V.; Afzal, R.; et al. HDAC Inhibitors Enhance T-Cell Chemokine Expression and Augment Response to PD-1 Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4119–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, A.; Shin, D.S.; Moreno, B.H.; Saco, J.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; Rodriguez, G.A.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Hugo, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1189–1201, Erratum in Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Postow, M.A.; Orlowski, R.J.; Mick, R.; Bengsch, B.; Manne, S.; Xu, W.; Harmon, S.; Giles, J.R.; Wenz, B.; et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 2017, 545, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Hamanishi, J.; Matsumura, N.; Abiko, K.; Murat, K.; Baba, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Horikawa, N.; Hosoe, Y.; Murphy, S.K.; et al. Chemotherapy Induces Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 Overexpression via the Nuclear Factor-κB to Foster an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 5034–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terranova-Barberio, M.; Pawlowska, N.; Dhawan, M.; Moasser, M.; Chien, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Rugo, H.; Rahimi, R.; Deal, T.; Daud, A.; et al. Exhausted T cell signature predicts immunotherapy response in ER-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.A.; Savas, P.; Virassamy, B.; O’Malley, M.M.R.; Kay, J.; Mueller, S.N.; Mackay, L.K.; Salgado, R.; Loi, S. Towards targeting the breast cancer immune microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plitas, G.; Konopacki, C.; Wu, K.; Bos, P.D.; Morrow, M.; Putintseva, E.V.; Chudakov, D.M.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T Cells Exhibit Distinct Features in Human Breast Cancer. Immunity 2016, 45, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.R.; Li, F.; Montalvo-Ortiz, W.; Sepulveda, M.A.; Bergerhoff, K.; Arce, F.; Roddie, C.; Henry, J.Y.; Yagita, H.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1695–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, L.; Mahmoud, M.A.A.; Weaver, J.D.; Tijaro-Ovalle, N.M.; Christofides, A.; Wang, Q.; Pal, R.; Yuan, M.; Asara, J.; Patsoukis, N.; et al. Targeted deletion of PD-1 in myeloid cells induces antitumor immunity. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eaay1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Ruffell, B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Fragkogianni, S.; Sims, A.H.; Swierczak, A.; Forrester, L.M.; Zhang, H.; Soong, D.Y.H.; Cotechini, T.; Anur, P.; Lin, E.Y.; et al. Human Tumor-Associated Macrophage and Monocyte Transcriptional Landscapes Reveal Cancer-Specific Reprogramming, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 588–602.e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLane, L.M.; Abdel-Hakeem, M.S.; Wherry, E.J. CD8 T Cell Exhaustion During Chronic Viral Infection and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 37, 457–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, M.; Fairchild, L.; Sun, L.; Horste, E.L.; Camara, S.; Shakiba, M.; Scott, A.C.; Viale, A.; Lauer, P.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature 2017, 545, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, I.; Schaeuble, K.; Chennupati, V.; Fuertes Marraco, S.A.; Calderon-Copete, S.; Pais Ferreira, D.; Carmona, S.J.; Scarpellino, L.; Gfeller, D.; Pradervand, S.; et al. Intratumoral Tcf1(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T Cells with Stem-like Properties Promote Tumor Control in Response to Vaccination and Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Immunity 2019, 50, 195–211.e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.R.; Chlon, L.; Pharoah, P.D.; Markowetz, F.; Caldas, C. Patterns of Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Implications: A Gene-Expression-Based Retrospective Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.S.; Yang, H.; Chon, H.J.; Kim, C. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickup, M.W.; Mouw, J.K.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, W.; Shyer, J.A.; Zhao, J.; Canaveras, J.C.G.; Al Khazal, F.J.; Qu, R.; Steach, H.R.; Bielecki, P.; Khan, O.; Jackson, R.; et al. Distinct modes of mitochondrial metabolism uncouple T cell differentiation and function. Nature 2019, 571, 403–407, Erratum in Nature 2019, 573, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Dai, D.; Horton, B.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor-Residing Batf3 Dendritic Cells Are Required for Effector T Cell Trafficking and Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 711–723.e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, L.; Yau, C.; Wolf, D.M.; Han, H.S.; Du, L.; Wallace, A.M.; String-Reasor, E.; Boughey, J.C.; Chien, A.J.; Elias, A.D.; et al. Durvalumab with olaparib and paclitaxel for high-risk HER2-negative stage II/III breast cancer: Results from the adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 989–998.e985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; Shintaku, I.P.; Taylor, E.J.; Robert, L.; Chmielowski, B.; Spasic, M.; Henry, G.; Ciobanu, V.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Bindeman, W. Clinical applications of PD-L1 bioassays for cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacic, S. Time is up for PD-L1 testing standardization in lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 791–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J.H.; Lelkaitis, G.; Håkansson, K.; Vogelius, I.R.; Johannesen, H.H.; Fischer, B.M.; Bentzen, S.M.; Specht, L.; Kristensen, C.A.; von Buchwald, C.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurjonsdottir, G.; De Marchi, T.; Ehinger, A.; Hartman, J.; Bosch, A.; Staaf, J.; Killander, F.; Niméus, E. Comparison of SP142 and 22C3 PD-L1 assays in a population-based cohort of triple-negative breast cancer patients in the context of their clinically established scoring algorithms. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2023, 25, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; McArthur, H.; Pusztai, L.; Kümmel, S.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N.; et al. Overall Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelzer, V.H.; Gisler, A.; Hanhart, J.C.; Griss, J.; Wagner, S.N.; Willi, N.; Cathomas, G.; Sachs, M.; Kempf, W.; Thommen, D.S.; et al. Digital image analysis improves precision of PD-L1 scoring in cutaneous melanoma. Histopathology 2018, 73, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyerer, V.; Strissel, P.L.; Strick, R.; Sikic, D.; Geppert, C.I.; Bertz, S.; Lange, F.; Taubert, H.; Wach, S.; Breyer, J.; et al. Integration of Spatial PD-L1 Expression with the Tumor Immune Microenvironment Outperforms Standard PD-L1 Scoring in Outcome Prediction of Urothelial Cancer Patients. Cancers 2021, 13, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Cameron, D.; Gianni, L.; Valagussa, P.; et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 164–172, Erratum in Lancet 2019, 393, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Heo, S.H.; Song, I.H.; Rajayi, H.; Park, H.S.; Park, I.A.; Kim, Y.A.; Lee, H.; Gong, G.; Lee, H.J. Presence of tertiary lymphoid structures determines the level of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in primary breast cancer and metastasis. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostou, V.; Luke, J.J. Quantitative Spatial Profiling of TILs as the Next Step beyond PD-L1 Testing for Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4835–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez de Rodas, M.; Wang, Y.; Peng, G.; Gu, J.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Riess, J.W.; Velcheti, V.; Hellmann, M.; Gainor, J.F.; Zhao, H.; et al. Objective Analysis and Clinical Significance of the Spatial Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Patterns in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thagaard, J.; Stovgaard, E.S.; Vognsen, L.G.; Hauberg, S.; Dahl, A.; Ebstrup, T.; Doré, J.; Vincentz, R.E.; Jepsen, R.K.; Roslind, A.; et al. Automated Quantification of sTIL Density with H&E-Based Digital Image Analysis Has Prognostic Potential in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.; Michiels, S.; Adams, S.; Loibl, S.; Budczies, J.; Denkert, C.; Salgado, R. The journey of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as a biomarker in breast cancer: Clinical utility in an era of checkpoint inhibition. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luen, S.J.; Salgado, R.; Fox, S.; Savas, P.; Eng-Wong, J.; Clark, E.; Kiermaier, A.; Swain, S.M.; Baselga, J.; Michiels, S.; et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with pertuzumab or placebo in addition to trastuzumab and docetaxel: A retrospective analysis of the CLEOPATRA study. Lancet. Oncol. 2017, 18, 52–62, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Classification of triple-negative breast cancers based on Immunogenomic profiling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, F.; Aptsiauri, N.; Doorduijn, E.M.; Garcia Lora, A.M.; van Hall, T. The urgent need to recover MHC class I in cancers for effective immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016, 39, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Peng, P.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Li, H.; Shao, M.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; Duan, F.; et al. Decreased expression of STING predicts poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihama, S.; Vijayan, S.; Sidiq, T.; Kobayashi, K.S. NLRC5/CITA: A Key Player in Cancer Immune Surveillance. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Nong, Q.; Tao, S.; Lu, B.; Yu, Y.; Peng, H.; Tian, Y.; Su, Q.; et al. CEACAM6 as a machine learning derived immune biomarker for predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in HR+/HER2− breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1662004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; De Wilde, R.L.; Feng, R.; Su, M.; Torres-de la Roche, L.A.; Shi, W. A Machine Learning Model to Predict the Triple Negative Breast Cancer Immune Subtype. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 749459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.J.; Wolf, D.M.; Yau, C.; Brown-Swigart, L.; Wulfkuhle, J.; Gallagher, I.R.; Zhu, Z.; Bolen, J.; Vandenberg, S.; Hoyt, C.; et al. Multi-platform biomarkers of response to an immune checkpoint inhibitor in the neoadjuvant I-SPY 2 trial for early-stage breast cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Deng, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, H. Systematic evaluation of tumor microenvironment and construction of a machine learning model to predict prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy in triple-negative breast cancer based on data mining and sequencing validation. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 995555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, S.; Wang, X. Identification of Breast Cancer Immune Subtypes by Analyzing Bulk Tumor and Single Cell Transcriptomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 781848, Erratum in Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 948644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenza, C.; Saldanha, E.F.; Gong, Y.; De Placido, P.; Gritsch, D.; Ortiz, H.; Trapani, D.; Conforti, F.; Cremolini, C.; Peters, S.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA Clearance as a Predictive Biomarker of Pathologic Complete Response in Patients with Solid Tumors Treated with Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbanua, M.J.M.; Swigart, L.B.; Wu, H.T.; Hirst, G.L.; Yau, C.; Wolf, D.M.; Tin, A.; Salari, R.; Shchegrova, S.; Pawar, H.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer reflects response and survival. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, R.I.; Chen, K.; Usmani, A.; Chua, C.; Harris, P.K.; Binkley, M.S.; Azad, T.D.; Dudley, J.C.; Chaudhuri, A.A. Detection of Solid Tumor Molecular Residual Disease (MRD) Using Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA). Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 23, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Ge, H.; Qi, Y.; Zeng, C.; Sun, X.; Mo, H.; Ma, F. Predictive circulating biomarkers of the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced HER2 negative breast cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Espinoza, J.A.; Torland, L.A.; Zucknick, M.; Kumar, S.; Haakensen, V.D.; Lüders, T.; Engebraaten, O.; Børresen-Dale, A.L.; Kyte, J.A.; et al. Noninvasive profiling of serum cytokines in breast cancer patients and clinicopathological characteristics. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1537691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Zucknick, M.; Nome, M.; Dannenfelser, R.; Fleischer, T.; Kumar, S.; Lüders, T.; von der Lippe Gythfeldt, H.; Troyanskaya, O.; Kyte, J.A.; et al. Serum cytokine levels in breast cancer patients during neoadjuvant treatment with bevacizumab. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1457598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Schmitt, W.D.; Loibl, S.; Müller, B.M.; Blohmer, J.U.; Sinn, B.V.; Eidtmann, H.; Eiermann, W.; Gerber, B.; Tesch, H.; et al. Ki67 measured after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, C.E.; Straver, M.E.; Rodenhuis, S.; Muller, S.H.; Wesseling, J.; Vrancken Peeters, M.J.; Gilhuijs, K.G. Magnetic resonance imaging response monitoring of breast cancer during neoadjuvant chemotherapy: Relevance of breast cancer subtype. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, B.J.; Lee, A.W. Treatment Response Evaluation of Breast Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Usefulness of the Imaging Parameters of MRI and PET/CT. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 808–815, Erratum in J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.C.; Zhang, Z.; Newitt, D.C.; Gibbs, J.E.; Chenevert, T.L.; Rosen, M.A.; Bolan, P.J.; Marques, H.S.; Romanoff, J.; Cimino, L.; et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI Findings Predict Pathologic Response in Neoadjuvant Treatment of Breast Cancer: The ACRIN 6698 Multicenter Trial. Radiology 2018, 289, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhbahaei, S.; Trahan, T.J.; Xiao, J.; Taghipour, M.; Mena, E.; Connolly, R.M.; Subramaniam, R.M. FDG-PET/CT and MRI for Evaluation of Pathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Oncol. 2016, 21, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerouni, A.S.; Peterson, L.M.; Jenkins, I.; Novakova-Jiresova, A.; Linden, H.M.; Gralow, J.R.; Hockenbery, D.M.; Mankoff, D.A.; Porter, P.L.; Partridge, S.C.; et al. Multimodal prediction of neoadjuvant treatment outcome by serial FDG PET and MRI in women with locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengel, K.E.; Koolen, B.B.; Loo, C.E.; Vogel, W.V.; Wesseling, J.; Lips, E.H.; Rutgers, E.J.; Valdés Olmos, R.A.; Vrancken Peeters, M.J.; Rodenhuis, S.; et al. Combined use of 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI for response monitoring of breast cancer during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 41, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esserman, L.J.; Berry, D.A.; DeMichele, A.; Carey, L.; Davis, S.E.; Buxton, M.; Hudis, C.; Gray, J.W.; Perou, C.; Yau, C.; et al. Pathologic complete response predicts recurrence-free survival more effectively by cancer subset: Results from the I-SPY 1 TRIAL--CALGB 150007/150012, ACRIN 6657. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3242–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Olopade, O.I.; DeMichele, A.; Yau, C.; van ‘t Veer, L.J.; Buxton, M.B.; Hogarth, M.; Hylton, N.M.; Paoloni, M.; Perlmutter, J.; et al. Adaptive Randomization of Veliparib-Carboplatin Treatment in Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Assaf, Z.J.; Harbeck, N.; Zhang, H.; Saji, S.; Jung, K.H.; Hegg, R.; Koehler, A.; Sohn, J.; Iwata, H.; et al. Peri-operative atezolizumab in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: Final results and ctDNA analyses from the randomized phase 3 IMpassion031 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, L. Progress in research on paclitaxel and tumor immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2019, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantelidou, C.; Sonzogni, O.; De Oliveria Taveira, M.; Mehta, A.K.; Kothari, A.; Wang, D.; Visal, T.; Li, M.K.; Pinto, J.; Castrillon, J.A.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Efficacy Depends on CD8(+) T-cell Recruitment via Intratumoral STING Pathway Activation in BRCA-Deficient Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Xia, W.; Yamaguchi, H.; Wei, Y.; Chen, M.K.; Hsu, J.M.; Hsu, J.L.; Yu, W.H.; Du, Y.; Lee, H.H.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Upregulates PD-L1 Expression and Enhances Cancer-Associated Immunosuppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3711–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.; Martin, K.; Theurich, S.; Schreiner, J.; Savic, S.; Terszowski, G.; Lardinois, D.; Heinzelmann-Schwarz, V.A.; Schlaak, M.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; et al. Microtubule-depolymerizing agents used in antibody-drug conjugates induce antitumor immunity by stimulation of dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Layman, R.M.; Lynce, F.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; McRoy, L.; Cohen, A.B.; Estevez, M.; Curigliano, G.; Brufsky, A. Comparative overall survival of CDK4/6 inhibitors plus an aromatase inhibitor in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer in the US real-world setting. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Brufsky, A.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; McRoy, L.; Chen, C.; Layman, R.M.; Cristofanilli, M.; Torres, M.A.; Curigliano, G.; et al. Real-world study of overall survival with palbociclib plus aromatase inhibitor in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; Watt, A.C.; BrinJones, H.; Sceneay, J.; Li, B.B.; Khan, N.; Ubellacker, J.M.; Xie, S.; Metzger-Filho, O.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2017, 548, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, E.S.; Jenkins, R.W.; Li, S.; Dries, R.; Yates, K.; Chhabra, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Aref, A.R.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Augments Antitumor Immunity by Enhancing T-cell Activation. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Sun, X.; Feng, X.; An, Z. Interstitial lung disease in patients treated with Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Breast 2022, 62, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Liu, M.C.; Yee, D.; Yau, C.; van ‘t Veer, L.J.; Symmans, W.F.; Paoloni, M.; Perlmutter, J.; Hylton, N.M.; Hogarth, M.; et al. Adaptive Randomization of Neratinib in Early Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, D.A.; Beckmann, R.P.; Dempsey, J.A.; Huber, L.; Forest, A.; Amaladas, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Rasmussen, E.R.; Chin, D.; et al. The CDK4/6 Inhibitor Abemaciclib Induces a T Cell Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment and Enhances the Efficacy of PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2978–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Method | Decision Threshold | Supporting Evidence | Reference Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Tumor Selection | ||||

| PD-L1 expression | IHC (SP142 or 22C3) | Positive (CPS ≥ 10–20) | SP142 ≥ 1%: 44.3% pCR vs. 20.2% (CheckMate-7FL); 22C3 CPS ≥ 10: 29.7% pCR vs. 19.6% (KEYNOTE-756) | Section 4.1.1 |

| Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) | H&E stromal assessment | High density (≥40%) | ≥40%: 45–60% pCR (I-SPY2, CheckMate-7FL); 10–40%: 25–35% pCR; <10%: 10–15% pCR (KEYNOTE-756) | Section 4.1.2 |

| Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) | H&E + IHC (CD20/CD3/CD21) | Presence of mature TLS | TLS-positive: 2.5-fold higher pCR rates (IMpassion031, meta-analysis) | Section 4.1.2 |

| HLA class I expression | IHC | Preserved or restorable | Baseline ≥ 50%; Restoration > 2-fold within 2–3 cycles predicts response (I-SPY2) | Section 4.1.3 |

| ER expression level | IHC | Low (1–10%) | ER 1–10%: 24.5% pCR vs. 13.8% (CheckMate-7FL); ER ≤ 10% + PD-L1+: 44% pCR | Section 5.1.1 |

| Genomic signatures | MammaPrint, gene expression | MP Ultra-High 2 | MP2/High-2: 61% pCR vs. 21% control (I-SPY2 pembrolizumab); graduated with 99.6% probability | Section 4.1.4 |

| Favorable TME Cellular Composition | ||||

| M1 macrophages | IHC (CD68+iNOS+CD86+) | High M1 density | High M1/M2 ratio (>1.5) associated with improved response (multiple cohorts) | Section 2 |

| M2 macrophages | IHC (CD163+CD206+) | Low M2 density | Low M2/M1 ratio (<0.7); M2 > 40% TAMs predict poor response (meta-analysis, n = 12,439) | Section 2 |

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | IHC (FOXP3+) | Low Treg infiltration | Treg/CD8+ < 0.2; Effector/regulatory > 5:1 predicts 65% vs. 25% pCR (KEYNOTE-522) | Section 3.2.2 |

| Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) | Flow cytometry (blood) | Low circulating MDSC | MDSC < 5% of PBMCs indicates reduced immunosuppression (I-SPY2) | Section 3.2.2 |

| CD8+ T cells | IHC (CD8) | High density, central localization | Intratumoral CD8+ > 20%: 46% pCR vs. 15%; Central > marginal distribution (TNBC data, applicable to high-TIL HR+) | Section 3.1.2 |

| Dynamic Monitoring During Treatment | ||||

| Serial tumor biopsies | IHC panel (HLA-I, TILs, PD-L1) | Increasing TILs, restored HLA-I, TLS formation | >4-fold TIL increase baseline to cycle 3; HLA-I > 2-fold correlates with pCR (I-SPY2) | Section 4.2 |

| T cell activation markers | Flow cytometry (peripheral blood) | Activated CD8+ T cells (CD25+Ki-67+) | >2-fold increase CD8+CD25+Ki-67+ within 2 cycles; Effector/Treg > 5:1: 65% vs. 25% pCR (CheckMate-7FL) | Section 4.2 |

| Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Liquid biopsy | Rapid clearance | >2-log reduction by week 3 predicts 80% pCR vs. 20% slow clearance (I-SPY2 ctDNA analysis) | Section 4.2 |

| PD-L1 dynamic expression | Serial IHC | Treatment-induced upregulation | On-treatment upregulation indicates immune engagement; inverted U pattern (peak cycle 2–3) optimal (KEYNOTE-522, CheckMate-7FL) | Section 4.2 |

| Imaging biomarkers | MRI (ADC), PET-CT (SUVmax) | ADC decrease, metabolic changes | ADC > 15% decrease by week 3: 82% sensitivity; SUVmax > 60% reduction: 75% PPV for pCR (meta-analysis) | Section 4.2 |

| Type of BC | Stage | Trial/NCT Number | Treatment Arms | N | Biomarker | Primary Endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR+/HER2− (T1c-2 N1-2 or T3-4 N0-2; ER ≥ 1%) | Stage II–III | CheckMate-7FL (NCT04109066) | A: Nivolumab + T-AC → Surgery → Nivolumab + ET | 263 | ER 1–10% or ER ≥ 1% | pCR Rate | Completed—pCR: 24.5% vs. 13.8% (p = 0.0021); higher benefit in PD-L1+ subgroup (VENTANA SP142 ≥ 1%: 44.3% versus 20.2%, respectively) |

| B: Placebo + T-AC → Surgery → Placebo + ET | 258 | ||||||

| HR+/HER2− (grade 3 high-risk invasive breast cancer (T1c-2, cN1-2 or T3-4, cN0-2)) | Stage II–III | KEYNOTE-756 (NCT03725059) | A: Pembrolizumab + Paclitaxel/Carboplatin → AC → Surgery → Pembrolizumab | 635 | Grade 3, high-risk | pCR (ypT0/Tis ypN0) + EFS | Ongoing—pCR: 24.3% vs. 15.6% (p = 0.00005); higher benefit in PD-L1+ (29.7% vs. 19.6%); EFS was not mature in this analysis. |

| B: Placebo + Paclitaxel/Carboplatin → AC → Surgery → Placebo | 643 | ||||||

| HR+/HER2− | Stage II–III | SWOG S2206 (NCT06058377) | A: Durvalumab + neoadjuvant AC + paclitaxel followed by adjuvant ET | N/A | MP2/High-2 | EFS | Recruiting—Testing durvalumab in high-risk HR+ BC based on I-SPY2 results |

| B: Placebo + neoadjuvant AC + paclitaxel followed by adjuvant ET | N/A | ||||||

| TNBC | Stage II–III | KEYNOTE-522 (NCT03036488) | A: Pembrolizumab + Paclitaxel/Carboplatin → AC → Surgery → Pembrolizumab | 784 | PD-L1 (all patients included regardless of status) | pCR + EFS (dual primary) | Completed—FDA approved standard of care; pCR: 64.8% vs. 51.2%; OS HR = 0.66 |

| B: Placebo + Paclitaxel/Carboplatin → AC → Surgery → Placebo | 390 | EFS HR = 0.63; 5-year OS: 86.6% vs. 81.7% | |||||

| TNBC | Early Stage | IMpassion031 (NCT03197935) | A: Atezolizumab + Nab-paclitaxel → AC | 165 | ctDNA | pCR rate | Completed-pCR: 57.6% vs. 41.1%; improved pCR in PD-L1+ patients (69% vs. 49%) |

| B: Placebo + Nab-paclitaxel → AC | 168 | ||||||

| TNBC/HR-low/HER2− | Stage II–III treatment-naive | TROPION-Breast04 (NCT06112379) | A: Datopotamab deruxtecan + Durvalumab → Surgery → Durvalumab | N/A | N/A | pCR, EFS | Ongoing-Challenge to KEYNOTE-522 standard |

| B: Standard of care (Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy per KEYNOTE-522) | N/A | Based on BEGONIA study (ORR 79%) | |||||

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT06627712 | A: SBRT + PD-1 inhibitor + Chemotherapy | Recruiting | N/A | pCR rate, Safety | Not yet recruiting—Novel radiotherapy + immunotherapy combination |

| Type of BC | Stage | Trial/NCT Number | Treatment Arms | N | Biomarker | Primary Endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE II | |||||||

| HR+/HER2− | Stage II–III | I-SPY2 (NCT01042379) | A: Pembrolizumab + Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 40 | 13 mRNA markers | pCR rate | pCR: 30% vs. 13% (control) |

| B: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (control) | 96 | ||||||

| HR+/HER2− | Stage II–III | I-SPY2 (NCT01042379) | A: Durvalumab + Olaparib + Paclitaxel → AC | 52 | 13 mRNA markers | pCR rate | pCR: 28% vs. 14% (control) |

| B: Control (NACT): paclitaxel → AC | 299 | ||||||

| HR+/HER2− | Stage II–III | I-SPY2 (NCT01042379) | Durvalumab + T-AC | N/A | MammaPrint high-risk | pCR rate | Did not graduate—insufficient efficacy signal |

| HR+/HER2− (Luminal B-like only) | Early Stage | GIADA | Sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by nivolumab + endocrine therapy | N/A | Luminal B | Safety, Feasibility | Completed—acceptable safety profile |

| HR+/HER2− | Stage II–III | NCT06639672 | PD-1 inhibitor + Chemotherapy + Different RT fractionations (4 arms) | Recruiting | N/A | pCR rate | Not yet recruiting—Immunotherapy + RT fractionation study |

| HR+/HER2-low and HER2− | T1b-c N0 or T1 N1 | OlympiaN (NCT05498155) | A: Olaparib + Durvalumab | N/A | gBRCA mutation | pCR rate | Recruiting—PARP inhibitor + immunotherapy |

| B: Olaparib alone | N/A | ||||||

| HR-low/HER2− | Early Stage | NCT05749575 | Chidamide + Toripalimab + Paclitaxel | 28 | Low HR expression | tpCR rate (ypT0/is, ypN0) | Unknown status |

| HER2− | Stage II–III | NCT05761470 | Camrelizumab + Fluzoparib + Nab-paclitaxel | N/A | HRD | pCR rate | Chinese trial—PARP + PD-1 combination |

| HER2-low | Stage II–III | NCT05726175 | Disitamab vedotin (RC48) + Penpulimab (PD-1) | N/A | HER2-low (IHC 1+ or 2+/ISH-) | pCR rate | West China Hospital—completed; manageable safety demonstrated |

| HER2+ and HER2-low | Stage III Inflammatory breast cancer | TRUDI (NCT05795101) | Trastuzumab deruxtecan + Durvalumab | Recruiting | HER2+ or HER2-low (IHC 1+/2+) | pCR rate | Dana-Farber/MD Anderson; First antibody–drug conjugate + immunotherapy for IBC |

| HER2+ | Early Stage | Keyriched-1 (NCT03988036) | Pembrolizumab + Trastuzumab + Pertuzumab | N/A | HER2+ | pCR rate | Ongoing—Immunotherapy + dual HER2 blockade |

| TNBC | High-risk early stage | I-SPY2.2 (NCT01042379) | Datopotamab deruxtecan + Durvalumab | Recruiting | Adaptive biomarker-driven | pCR rate | New I-SPY platform arm; Based on BEGONIA results |

| TNBC | Early Stage | Neo-CheckRay (NCT03875573) | Durvalumab + oledumab + AC + paclitaxel followed by preoperative radiation | N/A | cT1-3 cN-1, ER+ ≤ 5% or grade 3, or MP high risk | Safety run-in, tumor response, pCR, and RCB | Recruiting |

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT04418154 | Toripalimab + Dose-dense EC → Nab-paclitaxel | N/A | N/A | pCR rate | Ongoing—Chinese PD-1 inhibitor with dose-dense chemotherapy |

| TNBC (High TILs) | Early Stage | NCT05556200 | Camrelizumab + Apatinib | N/A | High TILs (≥20%) | pCR rate | Ongoing—Chinese PD-1 + anti-angiogenic combination |

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT06802757 | A: Posaconazole + Pembrolizumab + Chemotherapy | Recruiting | N/A | pCR rate | Not yet recruiting—Novel antifungal + immunotherapy combination |

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT05582499 | Camrelizumab + Chemotherapy | N/A | N/A | pCR rate | Ongoing—Chinese Camrelizumab with standard chemotherapy |

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT07011823 | Pembrolizumab + Partial breast irradiation | Recruiting | N/A | Safety, pCR rate | Not yet recruiting—Immunotherapy + partial breast RT |

| PHASE I/II | |||||||

| ER+/HER2− | Early stage | CheckMate 7A8 | Neoadjuvant Nivolumab + Palbociclib + Anastrozole | N/A | N/A | Safety, pCR rate | Ongoing—CDK4/6 inhibitor + PD-1 + AI combination |

| Luminal B HER2-/TNBC | Localized | B-IMMUNE (NCT03356860) | Durvalumab + Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | N/A | Luminal B or TNBC | Safety, pCR rate | Completed—18.8% pCR in luminal B, 45.5% in TNBC |

| PHASE I | |||||||

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT07178171 | QL1706 (PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific) + Short-cycle anthracyclines/taxanes | 30 | N/A | pCR rate | Not yet recruiting |

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT03197389 | Pembrolizumab (biomarker study) | N/A | Multiple biomarkers | Safety, Biomarker analysis | Completed—Biomarker identification study |

| Other-Observational | |||||||

| TNBC | Early Stage | NCT06448169 | Observational study on PD-1 inhibitor sensitivity | 200 | N/A | pCR rate | Not yet recruiting—Predictive biomarker identification |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Z.; Huang, T.; Yang, T. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming to Combination Therapy Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311596

Tang Z, Huang T, Yang T. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming to Combination Therapy Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311596

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Zimei, Tao Huang, and Tinglin Yang. 2025. "Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming to Combination Therapy Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311596

APA StyleTang, Z., Huang, T., & Yang, T. (2025). Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming to Combination Therapy Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311596