Abstract

Traditional nanoparticle synthesis methods often rely on hazardous chemicals, raising concerns about their environmental impact. This study reports the green synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using aqueous extracts from three distinct parts of Agave tequilana: the stalk (ZnO-S), heart (ZnO-H), and leaves (ZnO-L). The aim was to explore the influence of the different plant parts, each with their respective phytochemical profile, on the structural, optical, and antibacterial properties of the resulting nanoparticles. The synthesized ZnO-NPs were extensively characterized using UV–Vis spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR, X-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The results revealed that ZnO-S exhibited the smallest particle size (~18.3 nm), the highest crystallinity, and the most uniform morphology. Optical analysis showed bandgap energies of 3.13 eV (ZnO-S), 2.99 eV (ZnO-H), and 3.02 eV (ZnO-L), with ZnO-S demonstrating enhanced UV absorption and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation potential. Antibacterial assays against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli confirmed strong bactericidal activity for all samples, with ZnO-S showing the largest inhibition zones, approaching the efficacy of the reference antibiotic kanamycin. This work highlights the fundamental roles of plant-derived phytochemicals as natural reducing and capping agents and emphasizes the valorization of agave stalk and leaves, traditionally treated as agricultural waste for cost-effective and eco-friendly nanomaterial production. The findings reveal the untapped potential of Agave tequilana as a sustainable source for high-performance nanomaterials, paving the way for green innovations in antimicrobial and environmental applications.

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is a rapidly advancing field of modern research with wide-ranging applications across science and technology. It enables the fabrication of novel materials at the nanoscale level, characterized by unique features such as morphology, size, and distribution [,]. Nanoparticles (NPs) can be synthesized via physical, chemical, or biological approaches. Physical methods, such as pulsed laser deposition, sputtering, molecular beam epitaxy, and thermal evaporation, typically require high energy input, elevated temperatures, and a pressure system [,,]. Chemical approaches, including sol–gel, hydrothermal, solvothermal, spray pyrolysis, and microwave-assisted synthesis, offer greater control over NPs properties [,]. Nonetheless, both physical and chemical synthesis methodologies possess inherent limitations. Physical methods force substantial energy input, increased temperatures, and pressures, leading to time-consuming procedures, whereas chemical approaches utilize harmful substances that may pose a threat to the environment [,]. Consequently, green synthesis methods have emerged as an ideal alternative due to their environmental sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and exclusion of hazardous chemicals [,]. These methods are safe, non-toxic, and enable facile, one-step synthesis with control over NPs’ size and morphology []. Among various metal oxide (MO) nanoparticles, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) have received significant attention owing to their versatile functionalities, affordability, and biocompatibility with organisms at the molecular level [,].

ZnO-NPs synthesized via green methods exhibit physicochemical, biodegradable, and biocompatible properties, making them suitable for a broad range of applications [,], in which antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and/or wound-healing activities are of great relevance [,,]. Such characteristics of ZnO-NPs, coupled with their versatile optical, catalytic, and mechanical properties, make them integral to advanced materials science to address critical healthcare challenges and drive sustainable technological innovations across the industrial and biomedical sectors []. The optical, electrical, and catalytic properties of ZnO-NPs can be finely tuned by modifying their particle size, doping with other elements, or altering their crystalline structure []. These tunable features influence essential performance characteristics, including surface area, bandgap energies, and photocatalytic characteristics []. Enhanced properties, such as ROS (reactive oxygen species) generation, make ZnO-NPs highly effective against pathogens and valuable in healthcare settings [,].

In green synthesis, plant-derived phytochemicals such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, tannins, phenolic, and carboxylic acids act as potent reducing and capping agents [,,]. These bioactive compounds facilitate the chelation and reduction of metal ions, e.g., Zn2+, forming coordination intermediates that convert into ZnO upon calcination []. According to some published works, the diverse functional groups in phytochemicals play a key role in particle stabilization, control over geometry, and eco-friendly synthesis conditions [,,]. The success of this method depends almost entirely on the specific phytochemical profiles of the plant sources used. Numerous plant-based studies have demonstrated the successful synthesis of ZnO-NPs using extracts from leaves, flowers, seeds, pulp, or aerial parts of different species, as summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, some works have reported the production of composite ZnO-based materials, such as Ag/ZnO [], ZnO/MgO [], or CuxO/ZnO [] through phytoextract-mediated processes. However, the potential of using different structural parts from a single plant source remains largely unexplored.

Table 1.

A summary and comparison of the phyto-assisted synthesis of ZnO-NPs using natural extracts of different plants, showing (as the main contribution of each work) the size and shape of the particle obtained, as well as the application assessed.

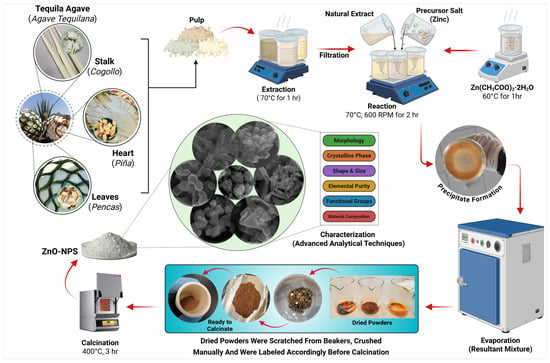

The present research aims to comparatively evaluate ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from extracts derived from three different plant parts, namely the Stalk (Cogollo), Heart (Piña), and Leaves (Pencas) of Agave tequilana, a plant locally known as Agave Azul in Mexico (see Figure 1). Agave tequilana belongs to the family Asparagaceae, subfamily Agavoideae, and is native to several Mexican states, including Jalisco, Colima, Nayarit, Michoacan, and Aguascalientes []. It flourishes in semi-arid climates at an altitude above 1500 m (~5000 feet) and grows well in sandy, nutrient-rich soils. This rosette-forming succulent contains spiky, fleshy leaves, which can grow over 2 m (~7 feet) in length []. Agave tequilana stands as a vital economic driver in Jalisco, Mexico, renowned worldwide as the foundation of Tequila production and a hallmark of regional identity. From the Agave tequilana plant, three parts can be identified: the stalk, the heart, and the leaves.

Figure 1.

The various parts of the Agave tequilana plant utilized in the extraction process for the synthesis of ZnO-NPs.

The stalk, locally known as cogollo, is often regarded as waste and is usually removed at an early stage to ensure that the heart (piña) maintains the highest concentration of sugars essential to high yields in Tequila production. Regardless of this, it presents a unique opportunity for sustainable repurposing. Its rich chemical composition and underexplored properties make it a fascinating candidate for innovative applications. Utilizing the stalk not only reduces environmental waste but also offers exciting possibilities for experimental research, bridging the gap between conventional practices and modern sustainability-driven exploration. The heart, or piña, as farmers also know it, is rich in agavins-branched oligosaccharides, predominantly composed of fructose [,], emphasizing its industrial and economic significance, which makes it a commercially valuable resource and a key factor in its suitability for the production of Tequila. The leaves, or pencas, are traditionally removed and discarded during Tequila production, as they play no significant role in the beverage’s processing. Instead, these leaves have long been valued in rural communities for their lasting fibers. They have been cleverly used in artisanal crafts to create essential items such as ropes, nets, bags, sacks, and mats.

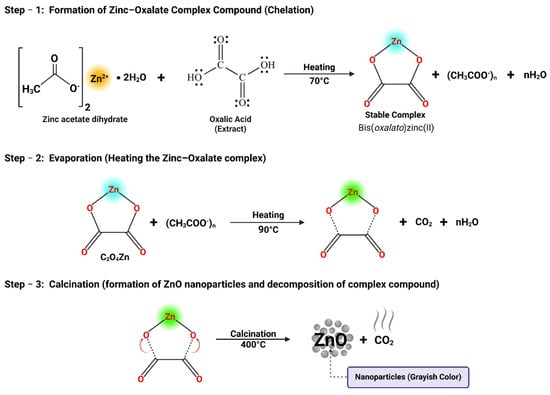

These parts of Agave tequilana possess unique phytochemical and organic compositions, including oxalic acids, alkaloids, steroids, glycosides, polyphenols, terpenoids, flavonoids, aromatic hydrocarbons, and resins [,], which vary significantly in their uses, ranging from economic products to agricultural waste. Such an approach not only expands the understanding of this plant’s untapped potential but also makes it ideal for evaluating structural influence on NPs synthesis, as they facilitate stabilization and reduction reactions. The potential reaction mechanism for the synthesis of ZnO-NPs using natural extracts is illustrated in Figure 2. In this mechanism the oxalic acid derived from the carboxylic acids class of phytochemicals reacts with the precursor salt and binds with Zn2+ ions, forming a stable coordination compound bis(oxalate)zinc (II) or zinc oxalate, while acetate ions remain dissolved in the liquid medium, as shown in the following reaction:

Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O + C2H2O4·nH2O → C2O4Zn + 2CH3COO− + 2H2O

C2O4Zn + 2CH3COO− + 2H2O → ZnO + CO2 + nH2O

Figure 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the formation of ZnO using natural extract as precursor. The scheme summarizes the sequential steps involved: chelation of zinc ions to form a zinc–oxalate complex, solvent evaporation upon heating, and subsequent calcination leading to the decomposition of the coordination compound and the formation of ZnO nanoparticles.

To evaporate the water residue, the solution is heated at 80–90 °C, where partial decomposition takes place, and dried precipitates of zinc oxalate are obtained. Afterwards, thermal decomposition at high temperature breaks the stable coordination compound, yielding the crystallized ZnO-NPs and releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) molecules.

Previous studies involving Agave species have contributed to green ZnO synthesis: for example, Agave americana extract has been used to prepare ZnO@C nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity [], and Agave tequilana lignin has been combined with ZnO nanoparticles for skin photoprotection []. Reports on other Agave species are few or focus on different nanomaterials or downstream applications. The present study explores the green synthesis of ZnO-NPs using extracts derived from distinct parts of Agave tequilana, aiming to establish a comparative understanding of their efficiency and suitability in sustainable nanomaterial production. Considering that each plant part exhibits a unique phytochemical profile, the investigation provides valuable insight into how these differences influence the physicochemical and functional properties of the resulting nanoparticles. This approach underscores the relevance of Agave tequilana as an underexplored yet promising resource for sustainable nanotechnology. Synthesized NPs were thoroughly characterized by advanced analytical techniques, including UV-Vis spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). These methods offered detailed insights into the morphology and size of the NPs, crystalline structure, band gap, and elemental composition. In addition, the antibacterial efficacy of the NPs was evaluated to determine which plant part produces the most effective ZnO-NPs for potential biomedical use. This comprehensive approach not only reinforces the ecological and functional value of Agave tequilana but also underscores its relevance as a sustainable resource in the development of eco-friendly nanomaterials. Ultimately, the findings pave the way for innovative plant-based strategies in antimicrobial research and make a meaningful contribution to advancing green nanotechnology.

2. Results

The UV-Vis spectroscopy study was conducted at three different stages of the synthesis process, namely (1) before the reaction, which refers to the extracts obtained from the parts of the Agave tequilana plant and before being mixed with the precursor salt; (2) after the reaction, referring to the dry powders obtained after mixing with the extracts but before subjecting them to a calcination process; and (3) after the powders were calcinated in the furnace. The analysis at these three stages was performed to monitor the formation of ZnO-NPs throughout the different steps of the synthesis from natural extracts of different parts of the Agave tequilana plant: the stalk (identified as “S”), the heart (identified as “H”), and the leaves (identified as “L”). Analysis of the optical properties at each stage provided relevant information on the evolution of the synthesized samples from the precursor salt to the production of zinc oxide, allowing for greater insight into what happens in each step of the synthesis and highlighting the importance of each step of the synthesis process, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(a) UV-Vis spectra of Agave tequilana extracts and the precursor salt, (b) UV-Vis spectra of ZnO powders before calcination, (c) UV-Vis spectra of calcinated ZnO-NPs, (d) energies of bandgap, and (e) conduction and valence band energy positions of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L samples. The green-shaded region in spectra (a–c) highlights the absorption region of the samples.

The initial UV–Vis spectra of the plant extracts demonstrate individual absorption features for the stalk (Extract “S”), heart (Extract “H”), and leaves (Extract “L”) in the range 230–300 nm (see Figure 3a). Extract S exhibits two absorption peaks at 240 nm and 255 nm, Extract H presents an absorption peak at 235 nm, whereas Extract L displays a single intense peak at 274 nm. All these peaks are characteristic of π–π* transitions in aromatic rings, commonly associated with phytochemicals such as flavonoids, tannins, carboxylic acids, and phenolic acids [,,]. These biomolecules are known to play key roles in reducing and stabilizing metal ions during phyto-assisted NP synthesis. The observed variation in absorption maxima and spectral profiles among the extracts suggests differences in secondary metabolite composition throughout the stalk, heart, and leaves of Agave tequilana. Notably, Extract L showed a broader, more intense peak at 274 nm, indicating a higher concentration or greater diversity of UV-active phytoconstituents. This observation supports the typically richer metabolite profile commonly found in the plant leaves. In contrast, the spectrum of the precursor salt (“P-Salt”—zinc acetate dihydrate) showed no significant absorption in the 230–300 nm range, indicating the absence of such bioactive organic molecules in the precursor salt. This spectral baseline serves as an essential control, confirming that the UV absorption features observed in the extracts arise purely from plant-derived phytochemicals.

Figure 3b presents the UV–Vis absorption spectra of the synthesized ZnO powders before the calcination phase. All samples exhibit broad absorption bands around 324 nm, symbolic of Zn-containing intermediate species. These absorption features are likely attributed to the formation of zinc oxalate or related zinc–organic complexes [], arising from interactions between Zn2+ ions and phytochemicals in the extracts. Organic acids such as oxalic and malic acids, present in the plant material, likely coordinate with Zn2+ to form intermediates like zinc oxalate hydrate (C2O4Zn·nH2O). These complexes typically exhibit ligand-to-metal charge-transfer bands, which account for the observed UV absorption. Notably, ZnO-L exhibits the highest absorbance intensity, followed by ZnO-H and ZnO-S, suggesting possible differences in the concentrations of these intermediates, depending on the extract composition. A broad peak around 324 nm in the ZnO-L spectrum further supports the presence of coordinated zinc–organic species. The spectral profiles suggest that ZnO synthesis initially proceeds via stable zinc–organic intermediates, with zinc oxalate likely serving as a key transitional phase that may decompose upon calcination to yield crystalline ZnO.

Figure 3c illustrates the UV–Vis absorption spectra of calcinated ZnO-NPs. All samples exhibit strong, sharp absorption bands around 362 nm, a region typically associated with electron transitions in ZnO [,]. This shift in spectral features, compared with the broader absorption bands observed before calcination, highlights the critical role of the calcination step. Calcination enables the thermal decomposition of zinc oxalate intermediates formed during the initial phyto-assisted green synthesis into ZnO. The disappearance of the broad UV absorptions associated with zinc–organic complexes, along with the emergence of sharp absorption edges, suggests the effective removal of organic constituents and the development of well-defined ZnO structures. The observed variations in absorbance intensity and edge definition among the samples suggest differences in nanoparticle size, potentially arising from the specific phytochemical composition of each extract. Tauc’s equation was employed to estimate the optical band gap (Eg) values for ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L samples, as presented in Figure 3d. The calculated Eg values were subsequently used to determine the conduction band (ECB) and valence band (EVB) positions of the NPs through standard empirical relations. Among the three samples, ZnO-S exhibited the highest optical Eg value of 3.13 eV. The corresponding ECB and EVB positions were calculated to be −0.18 eV and 2.95 eV, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 3e. This relatively wide band gap indicates efficient UV light absorption, which is a hallmark of small particle sizes where defect states rather than quantum confinement influence the optical transitions []. Economically, the stalk of Agave tequilana is underutilized, offering a sustainable pathway for the synthesis of high-performance materials.

ZnO-H NPs exhibit an absorption slightly shifted towards longer wavelengths compared to ZnO-S, correlating to an Eg of 2.99 eV. The ECB and EVB positions are calculated at −0.11 eV and 2.88 eV, respectively. The slightly lower ECB position compared to ZnO-S enhances the ability of ZnO-H to reduce oxygen molecules into reactive superoxide anions (O2−). Additionally, the EVB energy remains high enough to generate hydroxyl radicals, making ZnO-H highly efficient in ROS production under light exposure. These features make ZnO-H a versatile material for photo-assisted applications under both UV and visible light conditions. Although the heart of Agave tequilana is best known for its economic value in Tequila production, its use in the green synthesis of nanomaterials offers an alternative pathway to generate added value from the plant, providing a sustainable means of producing multifunctional materials from agricultural resources.

ZnO-L NPs display an Eg value of 3.02 eV, with ECB and EVB positions at −0.11 eV and 2.91 eV, respectively. The reduced Eg enhances visible-light absorption, potentially making ZnO-L more efficient for photocatalytic and antibacterial applications under ambient light. From an economic standpoint, the use of Agave tequilana leaves, often considered agricultural waste, is a cost-effective, environmentally friendly method for producing ZnO-NPs. The ability of ZnO-L to leverage visible light for photo-assisted processes further expands its application potential.

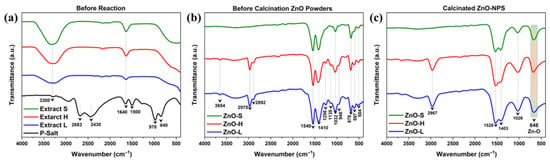

The FTIR spectra of Agave tequilana extracts and the precursor salt are presented in Figure 4a. In the plant extracts, a characteristic absorption band at ~1640 cm−1 was observed, which is attributed to the stretching vibrations of carbonyl groups (C=O). This absorption can be associated with the presence of aldehydes, ketones, and flavonoid derivatives, which are well-documented phytoconstituents of Agave species []. A broad band centered around ~3300 cm−1 corresponds to O–H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups, which is typically indicative of alcohols and phenolic compounds. The intensity and width of this signal suggest significant contributions from polyphenols, flavonoids, and saponins, confirming the abundance of hydroxylated phytochemicals in the extracts []. The presence of these functional groups is particularly relevant, as they are known to participate in metal ion chelation, reduction, and stabilization, thereby facilitating subsequent nanoparticle formation.

Figure 4.

(a) FTIR spectra of Agave tequilana extracts and precursor salt, (b) spectra of ZnO powders before calcination, and (c) spectra of calcinated ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L samples.

In contrast, the FTIR spectrum of the precursor salt (zinc acetate dihydrate) shows a band at ~840 cm−1 that corresponds to skeletal C–H vibrations of the acetate ligand, while the absorption near ~978 cm−1 is assigned to C–O stretching vibrations of acetate groups. A distinct feature at ~1500 cm−1 reflects CH3 deformation coupled with asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate group. In the mid-frequency region, the prominent band at ~1640 cm−1 is characteristic of H–O–H bending vibrations, confirming the presence of coordinated crystalline water. Two absorptions at ~2430 cm−1 and ~2683 cm−1 were observed, corresponding to O–C–O vibrational modes and aliphatic C–H stretching, respectively. Finally, the broad band centered around ~3300 cm−1 is attributed to O–H stretching vibrations of water molecules of crystallization []. The FTIR spectra of Agave tequilana extracts (Stalk, heart, leaves) evidenced the presence of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, indicative of polyphenols, flavonoids, or related phytochemicals with reducing and stabilizing potential. The precursor salt spectrum, on the other hand, was dominated by acetate- and water-related vibrations, consistent with the structural identity of zinc acetate dihydrate as the Zn2+ source.

The FTIR spectra of ZnO powders synthesized using the stalk (ZnO-S), heart (ZnO-H), and leaf (ZnO-L) extracts from Agave tequilana before calcination are presented in Figure 4b. Many absorption bands were observed, which reflect both the presence of ZnO lattice vibrations and the organic functional groups originating from the phytochemicals in the plant extracts. Several absorption bands were common across all three samples (ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L). The peaks appearing at 678, 597, and 504 cm−1 are characteristic of Zn–O stretching vibrations, indicating the formation of Zn–O bonds []. In addition, the absorption at 1032 cm−1 is attributed to C–O stretching vibrations of alcohols, esters, or polysaccharides []. The peak at 1410 cm−1 suggests the presence of organic molecules or functional groups associated with specific chemical bonds. It could be related to C-H bending vibrations in aliphatic compounds or stretching of carboxylate groups (−COO−) []. A strong band at 1540 cm−1 can be assigned to asymmetric carboxylate stretching and/or C=C stretching of the aromatic ring of phytochemicals []. The presence of these peaks in all three spectra indicates that similar groups of phytochemicals from different plant parts were present during the formation of ZnO-NPs.

In contrast, some additional absorption features were observed only in ZnO-H and ZnO-L, but were absent in ZnO-S. These include a broad band at 3654 cm−1 due to O–H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups from alcohols, phenols, or adsorbed water molecules []. The peaks at 2970 and 2892 cm−1 arise from the aliphatic C–H stretching of –CH2 and –CH3 groups, suggesting the contribution of terpenoids and fatty acid residues []. Moreover, the absorptions at 1256 and 1138 cm−1 may be associated with C=O stretching vibrations of carboxylic acid and C–O–C stretching of phenolics, esters, and polysaccharides [], while the band at 948 cm−1 can be associated with C-H bending vibrations in organic compounds, possibly indicating the presence of hydrocarbons or aliphatic groups []. The presence of these bands exclusively in ZnO-H and ZnO-L indicates that the heart and leaves of Agave tequilana harbor a greater diversity of phytochemicals, which may play an essential role in stabilizing and functionalizing the NPs. Overall, the FTIR results demonstrate that while all three plant parts contributed to NPs formation through similar functional groups, the extracts from the heart and leaves contained additional biomolecules that may enhance the capping and stabilization of ZnO-NPs.

The FTIR spectra of the calcinated ZnO powders derived from stalk (ZnO-S), heart (ZnO-H), and leaves (ZnO-L) are shown in Figure 4c. After calcination, the spectra show fewer absorption bands due to thermal removal of volatile organics and phytochemical residues, leaving mainly ZnO lattice vibrations with minor surface-bound functional groups. An absorption band at ~648 cm−1 is observed in all samples and is associated with the Zn–O stretching mode of wurtzite ZnO, confirming the formation of crystalline ZnO after calcination []. A weaker band at ~1026 cm−1 is associated with C–O stretching vibrations of alcohols, ethers, or polysaccharides []. The bands around 1403 cm−1 and 1528 cm−1 are associated with asymmetric and symmetric stretching of carboxylate groups (−COO−) [], respectively.

Additionally, in the higher wavenumber region, a distinct absorption at ~2967 cm−1 is observed in ZnO-H and ZnO-L, corresponding to aliphatic C–H stretching (–CH2/–CH3 groups) []. This band is notably absent in ZnO-S, which indicates a more complete removal of aliphatic organic residues during calcination in the stalk-derived sample. The difference suggests that the heart and leaves of Agave tequilana contain relatively higher proportions of aliphatic phytochemicals that remain weakly bound to the ZnO surface even after calcination. Overall, the FTIR spectra after calcination confirm that ZnO lattice vibrations dominate in all samples, while minor carboxylate and aliphatic groups persist, particularly in ZnO-H and ZnO-L, reflecting the influence of plant-part-specific phytochemical composition on NPs stabilization.

The crystalline structures of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L solid materials were studied by XRD. The resulting diffractograms before and after powder calcination are shown in Figure 5a,b, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 5a, the XRD patterns of the powders before calcination exhibit mostly low-intensity peaks, indicating that the ZnO precursor complexes formed during synthesis have not yet fully crystallized into ZnO-NPs. This phenomenon is typical of as-synthesized biogenic materials, where organic compounds and phytochemicals from plant extracts often inhibit full crystallization during the initial phase. These organic moieties likely act as stabilizers and may disrupt the long-range atomic ordering. On the other hand, Figure 5b demonstrates visibly different XRD patterns for the calcinated samples ZnO-S, ZnO-H and ZnO-L showing the diffraction peaks at 2θ values of approximately 31.73°, 34.44°, 36.35°, 47.56°, 56.69°, 62.85°, 66.44°, 68.01°, 69.16°, 72.56°, and 77.07°, which correspond, respectively, to the diffraction planes (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (004), and (202). All peaks match the diffraction pattern of ZnO, according to JCPDS card no. 96-210-7060. No secondary phases or impurity-related peaks were observed, indicating that the calcined products are single-phase crystalline ZnO. ZnO-S exhibited the most intense diffraction peaks, which may imply a higher degree of crystallinity compared to ZnO-H and ZnO-L. The relatively sharper peaks in ZnO-S could be influenced by the unique composition of the stalk extract, which may have affected crystal nucleation and growth during synthesis. In contrast, ZnO-H and ZnO-L showed broader and less intense peaks, which indicate a less crystalline structure.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of powders (a) before calcination and (b) after calcination of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L samples.

To further investigate the structural characteristics, the crystallite sizes (D) of the ZnO-NPs were calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation (Equation (1)), using the most intense diffraction peak for each sample. The shape factor (K) was set to 0.9, and the X-ray source used was Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction patterns is established as β in radians, along with Bragg’s angle (θ), which were used for the calculations of each sample separately to obtain the crystallite size. The crystallinity trend for each sample of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L were found to be 40.14 nm, 22.56 nm, and 18.46 nm, respectively, which coincides with the trend observed in the XRD diffractograms based on the width of the diffraction peaks.

Overall, the XRD analysis shows a clear structural transformation in the ZnO powders upon calcination. Before calcination, the samples exhibited a crystal structure characterized by a high-intensity peak at approximately 12°, which is more closely associated with the precursor salt and is entirely different from that of ZnO. Calcination at 400 °C for 3 h, applied to all samples, showed that this step is crucial for converting the materials to ZnO with high crystallinity, as evidenced by sharp, high-intensity diffraction peaks. The absence of impurity peaks suggests the formation of phase-pure ZnO. Among the samples, ZnO-S showed the smallest crystallite size, followed by ZnO-H and ZnO-L, highlighting the significant influence of the plant part used on the structural quality of the synthesized nanoparticles.

The surface morphology and particle distribution of the green-synthesized ZnO-NPs were examined using FESEM. The FESEM images in Figure 6a–c illustrate morphological variations across different plant parts used in the synthesis process. Additionally, Figure 6d provides an overview of the particle size distribution for ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L, offering further comprehension into the structural characteristics of the synthesized NPs.

Figure 6.

FESEM graphs of the green-synthesized ZnO-NPs (a) ZnO-S, (b) ZnO-H, and (c) ZnO-L showing variation in morphology and particle aggregation. (d) Nanoparticle size distribution, where the black markers within each box represent the mean value for each sample, and the black curve shows the normal distribution obtained from the measurements.

The FESEM micrography of Figure 6a shows the surface morphologies of calcinated ZnO-S NPs synthesized using the stalk extract of Agave tequilana. The image reveals that the NPs are highly agglomerated, forming irregular clusters with a notable presence of pyramid-shaped structures. These clusters appear to consist of smaller, well-defined primary particles with distinguishable granular structures. The morphology suggests uniform particle shape, with mostly spherical or near-spherical outlines. Figure 6b shows the morphology of calcined ZnO-H nanoparticles synthesized from the heart extract, displaying densely packed, predominantly spherical nanostructures that form a homogeneous, compact layer with minimal shape variation. The particle morphology of calcinated ZnO-L NPs synthesized using the leaves extract can be observed in Figure 6c. These NPs also show agglomerates comprising predominantly spherical or near-spherical particles, but they do not show the same compaction as that observed in the ZnO-H sample. FESEM analysis of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L revealed distinct yet comparable morphological characteristics, demonstrating the influence of the different parts of Agave tequilana (stalk, heart, and leaves) on ZnO-NP synthesis. All samples exposed agglomerated structures composed of predominantly spherical NPs with a high degree of uniformity. The particle size distribution of these ZnO-NPs was determined using ImageJ 1.54g software. The results, presented in the box plot of Figure 6d, reveal distinct average particle sizes and distributions for each sample, indicating that the precursor material influences NP size. The ZnO-S sample exhibited the smallest average particle size of 18.31 nm. The narrow distribution in the box plot indicates a high degree of uniformity, suggesting that the stalk precursor promoted the formation of smaller, more uniform NPs. This may be attributed to the specific biomolecules in the stalk that effectively stabilize nuclei during NPs formation. In contrast, the ZnO-H sample showed a slightly larger average particle size of 21.51 nm. The broader size distribution observed for ZnO-H shows a moderate increase compared to ZnO-S. The ZnO-L sample demonstrated the largest average particle size of 23.16 nm among the three samples.

The EDS analysis was employed to confirm the elemental composition and purity of the synthesized ZnO-NPs. EDS spectra for ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L presented in Figure 7a–c validate prominent peaks corresponding to zinc (Zn) and oxygen (O), as the primary elements of the analyzed materials. For ZnO-S the elemental composition by weight revealed a high Zn content of 81.2%, accompanied by 10.7% O, along with trace amounts of carbon (C, 7.3%) and calcium (Ca, 0.8%). Two clearly visible signals in the EDS spectrum of the ZnO-S sample have not been labeled or accounted for in the elemental analysis, since they correspond to aluminum (≈1.5 keV) and gold (≈2.1 keV) signals, coming from the pin where the sample was dispersed and the conductive coating added during the sample preparation, respectively. ZnO-H showed a Zn content of 72.6% and a relatively higher O percentage of 19.8%, along with small quantities of C (4.4%), magnesium (Mg, 2.1%), potassium (K, 1.0%), and Ca (0.2%). The slightly lower Zn and elevated O content, compared to ZnO-S, may suggest the presence of more oxygen-containing phytochemicals in the heart extract or a subtle variation in oxidation during synthesis. The detection of elements such as Mg and K is likely derived from natural minerals present in the plant extract [,]. In the case of ZnO-L, Zn is illustrated for 75.2% by weight, with O at 16.9% and C at 7.6%, along with a small amount of K (0.3%). The presence of K may stem from the intrinsic mineral content of the leaves extract []. The EDS results confirm the formation of zinc oxide, with Zn and O atomic ratios close to 1:1 in all three samples (ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L), indicating successful ZnO synthesis from each extract. Minor impurities such as C, Ca, Mg, and K are expected outcomes of green synthesis approaches using natural plant extracts. The comprehensive physicochemical characterizations confirm that the green synthesis approach using various parts of the Agave tequilana plant effectively yields ZnO-NPs with interesting features, including nanoscale size, well-defined morphology, and high crystallinity. Building upon these promising characteristics, the subsequent section explores the antibacterial activity of the synthesized NPs, assessing their practical relevance in biomedical applications.

Figure 7.

EDS spectra of the ZnO-NPs (a) ZnO-S, (b) ZnO-H, and (c) ZnO-L showing the elemental composition of the three samples.

Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial potential of the green-synthesized ZnO-NPs was systematically evaluated using the agar well diffusion method against Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) and Escherichia coli (Gram-negative). The inhibition zone (IZ) was measured after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, and the results are summarized in Table 2. Kanamycin, used as positive control, produced clear IZ against both Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, confirming the sensitivity of the assay (see Figure 8). In contrast, the negative control exhibited no antibacterial effect. All the green-synthesized ZnO-NPs demonstrated dose-dependent antibacterial activity against both bacterial strains, with the highest bactericidal response at the highest concentration (50 μg/mL). The pronounced bactericidal performance observed across these concentrations highlights the effective antimicrobial potential of ZnO-NPs synthesized using different parts of the Agave tequilana plant. These findings underscore the untapped potential of Agave as a sustainable source for producing bio-functional nanomaterials with promising applications in antimicrobial therapies.

Table 2.

Antibacterial efficacy of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L. Comparative analysis of inhibition zones across different concentrations against selected bacterial strains, reported as the average of triplicate measurements (n = 3).

Figure 8.

Inhibition zones demonstrating the antibacterial activity of green-synthesized ZnO-NPs against the S. aureus and E. coli. The numbers shown in each image correspond to the sample concentrations in µg/mL, and the letter “C” denotes the positive control (kanamycin).

A graphical comparison with statistical analysis of antimicrobial activity results is presented in Figure 9. Among the three samples studied in this work, ZnO-S showed the most pronounced antibacterial activity, particularly at higher concentrations. At 50 µg/mL, it produced an inhibition zone of 21.49 ± 0.52 mm against S. aureus and 20.18 ± 0.76 mm against E. coli, closely approaching the standard antibiotic Kanamycin (23.14 ± 0.38 mm and 22.53 ± 0.30 mm, respectively). This superior performance can be attributed to the smallest average particle size (~18.31 nm), which increases the surface-to-volume ratio and enhances interaction with bacterial membranes. Importantly, the stalk of the Agave tequilana plant is typically discarded as agricultural waste; hence, utilizing this part for NPs synthesis not only contributes to waste reduction but also adds economic value to an otherwise underutilized resource, making ZnO-S a sustainable and cost-effective candidate for large-scale production of nanomaterials with antibacterial performance. The mechanism of action for ZnO-S may involve multiple pathways: (i) generation of ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide anions that damage cellular components; (ii) direct attachment to the bacterial membrane, causing mechanical disruption and leakage of intracellular contents; and (iii) Zn2+ ion release, which interferes with bacterial enzyme activity and protein synthesis. The smaller particle size of ZnO-S may facilitate deeper penetration into bacterial cells, thereby enhancing its cytotoxic effects, especially against Gram-positive S. aureus, which lacks the protective outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 9.

Antibacterial activity of ZnO-S, ZnO-H, and ZnO-L against (a) S. aureus and (b) E. coli, evaluated across varying concentrations of ZnO-NPs, demonstrating a clear dose-dependent response of ZnO-NPs. Interestingly, at the highest concentration tested (50 μg/mL), the ZnO-S sample exhibited an effect comparable to that of kanamycin. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for six concentrations and the positive control (kanamycin). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

ZnO-H, synthesized from the heart of the Agave tequilana plant, the core commercially utilized in Tequila production, exhibited moderate yet significant antibacterial activity. At the highest concentration, it showed an inhibition zone of 18.02 ± 0.55 mm for S. aureus and 17.96 ± 0.53 mm for E. coli. While it is less effective than ZnO-S, its performance still underscores the bioactivity of NPs derived from economically valuable plant extracts. The moderate particle size (~21.57 nm) of ZnO-H suggests a slightly reduced surface reactivity compared to ZnO-S, possibly due to the difference in particle sizes. ZnO-L, synthesized from the leaves extract, a commonly discarded agricultural residue, demonstrated the least antibacterial activity, although still notable. At 50 µg/mL, it achieved IZs of 14.24 ± 0.68 mm for S. aureus and 15.92 ± 0.19 mm for E. coli. This relatively lower performance can be associated with its larger particle size (~23.16 nm). Nevertheless, the activity of ZnO-L remains relevant, particularly considering that it is synthesized from a plant part that is typically regarded as waste. Interestingly, all ZnO-NPs samples showed greater sensitivity toward S. aureus than E. coli at lower concentrations, which aligns with the known structural differences in bacterial cell walls. E. coli, as a Gram-negative bacterium, possesses an additional lipopolysaccharide outer membrane that offers enhanced protection. However, at higher ZnO-NPs concentrations, this resistance was overcome, as seen by the significantly increased inhibition zones.

3. Discussion

The use of nanomaterials has become increasingly relevant in medical and biotechnological fields, particularly in the search for new antimicrobial agents capable of addressing the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance. To meet these demands, it is essential to develop synthesis routes that ensure not only precise control over material properties but also environmental responsibility. Conventional chemical synthesis methods often rely on toxic reagents, posing risks to both human health and the environment. In contrast, green synthesis offers a sustainable and safer alternative, aligning with the principles of green chemistry by minimizing hazardous by-products and employing renewable resources.

In this context, the present study demonstrates the successful green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) using extracts from three different parts of the Agave tequilana plant: the heart, leaves, and stalk. The phytochemicals naturally present in these extracts act as reducing and stabilizing agents, enabling the formation of ZnO nanoparticles without the use of harmful chemicals. Characterization results confirm the efficient conversion of the precursor salt into ZnO with average particle sizes below 25 nm, validating the potential of Agave tequilana as a sustainable bioresource for nanomaterial production.

Calcination proved essential for defining the final nanoparticle morphology and crystal structure, enhancing crystallinity, and improving uniformity by removing residual organics. The combined influence of precursor composition and calcination conditions underscores the importance of controlling synthesis parameters to tune the physicochemical properties of ZnO-NPs for specific biomedical purposes.

Among the samples, ZnO-S synthesized from the Agave tequilana stalk extract exhibited the most promising results, highlighting the exceptional potential of this plant waste as a precursor for high-performance nanomaterials. The stalk and leaves, typically discarded during agave processing, were found to produce nanoparticles with suitable size and morphology for antimicrobial applications, transforming low-value agricultural residues into valuable raw materials for the synthesis of high-performance nanomaterials. This outcome represents a clear opportunity to apply circular economy principles to materials science, where waste valorization converges with sustainable innovation.

Moreover, the antimicrobial performance of the synthesized ZnO-NPs reinforces their potential as bioactive materials for the development of next-generation antimicrobial agents. By enabling the sustainable production of ZnO-NPs with strong bactericidal potential, this work demonstrates a viable route toward environmentally responsible nanomaterials that can help counteract antimicrobial resistance. Overall, the findings emphasize that the combination of green synthesis and waste valorization not only reduces environmental impact but also opens new pathways for designing functional materials with direct relevance to healthcare and biotechnology.

The antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs is generally attributed to three interconnected mechanisms: the generation of ROS, the release of Zn2+ ions, and direct interactions between the nanoparticles and the bacterial cell membrane. Numerous studies have shown that ROS production is strongly dependent on particle size. Smaller ZnO-NPs exhibit a higher surface-to-volume ratio, which promotes greater oxygen adsorption and more efficient electron–hole separation, ultimately enhancing ROS formation [,]. Particle size also affects the optical bandgap, as a reduction in crystallite size slightly widens the bandgap, facilitating increased ROS generation under ambient conditions [,]. These mechanistic considerations are consistent with our findings, as the smallest ZnO-NPs (stalk-derived) displayed the highest antibacterial activity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

Precursor salt Zinc-acetate-dihydrate [Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O], with a reagent-grade purity of ≥98%, was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and employed directly in the experimental procedures without any subsequent purification steps.

4.2. Collection of Plants (Agave tequilana)

Plant samples were carefully collected from their native habitats in full accordance with national and international regulatory standards, following the guidelines established by the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC-2001) []. The Agave tequilana plant and its parts were systematically collected from agricultural fields in the city of Tequila, located in the state of Jalisco, central Mexico (Latitude 32°88′32, Longitude 103°81′65″ W). This region is globally recognized as the heart of Tequila production in Mexico. The collected plant parts intended for extract preparation were thoroughly washed, first with tap water and then with deionized water, to remove any residual dust and soil particles. After washing, the samples were air-dried at room temperature (25 °C) to ensure proper dehydration. The stalk, heart, and leaves were subsequently chopped into small pieces to obtain the extract, and the remaining parts were labeled and carefully stored in polyethylene bags at −20 °C to preserve their quality for future experimentation.

4.3. Green Synthesis of ZnO-NPs Using Extracts of Different Parts of Agave tequilana

A 150 mL solution of the precursor salt was mixed individually with 75 mL of each prepared extract from the stalk, heart, and leaves of the Agave tequilana plant. Reaction conditions were optimized for each mixture and were set at 600 rpm stirring and 70 °C heating for a total of 120 min. As the reaction progressed in aqueous solutions, precipitation formed, and the color shifted from ivory cream to dark brown, forming a colloidal paste. This paste was then placed in a hot-air oven (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) at 80–90 °C for 4 h to evaporate any residual water molecules. At this point, a dried powdered sample was obtained. To achieve a finer, more uniform texture, the powder was ground in a mortar with a pestle. To further remove organic residues and obtain a crystalline product, the powders were calcined at 400 °C for 3 h. As a result, the calcinated ZnO-NPs exhibited a dark gray color and were marked as the final product. ZnO-NPs were stored in airtight containers at room temperature, avoiding sunlight for subsequent advanced analytical characterization. The entire green synthesis method is schematically illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the green synthesis process used to obtain ZnO nanoparticles from natural extracts derived from different parts of the Agave tequilana plant. The diagram illustrates the preparation of the extracts, their reaction with the zinc precursor, and the subsequent steps leading to the formation of ZnO-NPs.

4.4. Materials Characterization

A noticeable color change was observed when the precursor salt reacted with natural extracts of stalk, heart, and leaves. This shift in colors strongly indicates that a redox reaction was initiated between the extracts and the precursor salt. Various advanced characterization techniques, including UV–Vis, ATR–FTIR, XRD, FESEM, and EDS, were used to confirm the presence of ZnO-NPs and to thoroughly examine their properties. These techniques enabled the evaluation of the optical properties, identification of functional groups, analysis of particle morphology, assessment of crystalline structure, and determination of elemental composition of materials. The Cary-5000 UV–Vis-NIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was utilized to monitor the absorbance of ZnO-NPs, with measurements performed across a wavelength range of 200–800 nanometers (nm). The instrument was equipped with a poly-tetrafluoro-ethylene (PTFE) integration sphere. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) equipped with an attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory was utilized to evaluate the presence of organic matter and phytochemicals possibly responsible for the reduction and stabilization of ZnO-NPs. The ATR–FTIR spectra were recorded on an IR Affinity-1S spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) over the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a PANalytical 600 Powder X-ray Diffractometer (Malvern, United Kingdom). The measurements were conducted at a source voltage of 30 kV, utilizing a Cu Kα radiation source with a wavelength of 1.54 Å. The diffraction patterns were recorded over a range of 8° to 80°, with a step size of 0.05° and a scanning rate of 2°/min. Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) imaging was conducted using a Zeiss GeminiSEM 560 (Jena, Germany) equipped with an Oxford detector, operated at 30 kV. Additionally, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was performed using an EVO MA25 scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 30 kV. For FESEM and EDS analysis, the powder samples were dispersed onto aluminum pins and coated with a layer of gold.

4.5. Antibacterial Activity Assessment

The antibacterial performance of the synthesized ZnO-NPs was evaluated against two representative bacterial strains: Escherichia coli (ATCC 11229, Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538, Gram-positive). The bacterial cultures were prepared by growing the strains in nutrient broth at 37 °C for 24 h. For the antimicrobial assay, nutrient agar Petri dishes were prepared using a double-layer method. The base layer consisted of solidified nutrient agar, while the overlay was obtained by mixing 10 mL of nutrient agar (7.5 g/L) with 100 µL of an overnight-grown bacterial culture. After solidification, 5 µL drops of ZnO-NP solutions at concentrations of 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL were placed on the agar surface. Kanamycin (5 µL) was used as a positive control, and sterile 50% glycerol served as the negative control. Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Antibacterial efficiency was determined by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones (mm). All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Experimental data were statistically analyzed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test at a 95% confidence level. Statistical significance was indicated by asterisks according to the p-value: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the green synthesis of ZnO-NPs using extracts from distinct parts of the Agave tequilana plant: the stalk, heart, and leaves. Each component exhibited a significantly different influence on the properties of the synthesized NPs. ZnO-S, derived from stalk extracts, exhibited the smallest crystallite and particle sizes, with the highest antibacterial efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. ZnO-H and ZnO-L, synthesized from heart and leaves extracts, respectively, also demonstrated antibacterial activity but with lower efficacy than ZnO-S. In the phyto-assisted synthesis reported here, the calcination step proved crucial, transforming the precursors into highly crystalline ZnO-NPs, besides assisting in the removal of organic residues from the natural extracts. A key insight from this work is the crucial role played by plant-derived phytochemicals in the synthesis process. These compounds act as natural reducing and stabilizing agents, facilitating the formation of NPs with desirable characteristics. Future studies should focus on identifying and isolating specific phytochemicals responsible for these effects. Such investigations could deepen our understanding of their role in NPs stabilization, reduction processes, and potential alterations in particle properties.

The findings underscore the untapped potential of agricultural waste, such as stalks and leaves, which are traditionally discarded despite being valuable resources for producing high-performance nanomaterials. This approach not only mitigates environmental impact but also aligns with sustainable practices, promoting the valorization of agricultural residues. The results further establish Agave tequilana as a promising candidate for eco-friendly and cost-effective nanotechnology applications.

In conclusion, this research not only advances green nanotechnology by harnessing the inherent potential of Agave tequilana but also opens pathways for discovering innovative, sustainable solutions in the biomedical and environmental sectors. By converting agricultural waste into value-added materials, this study exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary science to drive eco-innovative breakthroughs, paving the way for future developments in eco-friendly nanomaterials with multifaceted applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.L.; methodology, G.M.C., A.B., J.G.S., E.S.-A. and J.L.M.-M.; validation, D.E.N.-L., E.R.L.-M. and A.L.S.-L.; formal analysis, G.M.C., S.O., D.E.N.-L., E.R.L.-M., A.L.S.-L. and L.M.L.; investigation, G.M.C., A.B., J.G.S., E.S.-A. and J.L.M.-M.; resources, A.L.S.-L. and L.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.O., D.E.N.-L., E.R.L.-M. and L.M.L.; visualization, G.M.C. and L.M.L.; supervision, A.L.S.-L. and L.M.L.; project administration, L.M.L.; funding acquisition, L.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by the Challenge-Based Research Funding Program of Tecnológico de Monterrey, grant number E090-EIC-GI04-A-T3-E. The APC was funded by Tecnologico de Monterrey.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Regina Vargas, from Tecnológico de Monterrey, for her outstanding support with SEM characterization. Ghulam Mustafa Channa expresses his sincere gratitude to Tecnológico de Monterrey (Mexico) for the Talent-Based Scholarship and for providing the resources and academic environment that made this work possible. Special thanks are also given to the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI, formerly CONAHCYT) for providing the stipend scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Anti-Microbial Resistance |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| ZnO-NPs | Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles |

| MO | Metal Oxide |

| MO-NPs | Metal Oxide Nanoparticles |

| ZnO-S | Zinc Oxide Stalk |

| ZnO-H | Zinc Oxide Heart |

| ZnO-L | Zinc Oxide Leaves |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| FESEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| mL | Milliliter |

| g | Gram |

| mg | Milligram |

| µg | Microgram |

| Eg | Bandgap |

| eV | Electron Volt |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| nm | Nanometer |

| mm | Millimeter |

| cm | Centimeter |

| L | Liter |

| IZ | Inhibition Zones |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

References

- Tiwari, A.; Shaik, A.H.; Brianna, B.; Anwar, A.; Chandan, M.R. Anti-cancer and antimicrobial efficacy of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized via green route using Amaranthus dubius (Spleen Amaranth) leaves extract. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2025, 18, 2453532. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeen, T.S.; Mohamed, H.E.A.; Maaza, M. ZnO nanoparticles prepared via a green synthesis approach: Physical properties, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 160, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, V.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Cuong, H.N.; Saini, A.; Saini, R.V.; Van Le, Q.; Nadda, A.K.; Le, T.-T.; Nguyen, V.-H. Sustainable and green trends in using plant extracts for the synthesis of biogenic metal nanoparticles toward environmental and pharmaceutical advances: A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 202, 111622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Jan, H.; Shah, S.A.; Shah, S.; Khan, A.; Akbar, M.T.; Rizwan, M.; Jan, F.; Wajidullah; Akhtar, N. Green synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using aqueous fruit extracts of Myristica fragrans: Their characterizations and biological and environmental applications. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9709–9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshi, N.; Prashanthi, Y.; Rao, T.N.; Ahmed, F.; Kumar, S.; Oves, M. Biosynthesis of ZnO nanostructures using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and their effect on seed germination and seedling growth of tomato: An eco-friendly approach. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2020, 15, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, M.C.; Gaudiuso, C.; Volpe, A.; Izzi, M.; Picca, R.A.; Ancona, A.; Cioffi, N. Biogenic synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their application as bioactive agents: A critical overview. Reactions 2022, 3, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Salazar, M.I.; Niño-Castaño, V.E.; Dueñas-Cuellar, R.A.; Caldas-Arias, L.; Fernández, I.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. Chemical synthesis versus green synthesis to obtain ZnO powders: Evaluation of the antibacterial capacity of the nanoparticles obtained by the chemical method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaky, A.S.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Babalghith, A.O.; Selim, S.; Mohamed, A.M.J.A. Green synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles using Pelargonium odoratissimum (L.) aqueous leaf extract and their antioxidant, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusefi, M.; Shameli, K.; Ali, R.R.; Pang, S.-W.; Teow, S.-Y. Evaluating anticancer activity of plant-mediated synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles using Punica granatum fruit peel extract. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1204, 127539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad Khan, M.; Lone, S.A.; Shahid, M.; Zeyad, M.T.; Syed, A.; Ehtram, A.; Elgorban, A.M.; Verma, M.; Danish, M. Phytogenically synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) potentially inhibit the bacterial pathogens: In vitro studies. Toxics 2023, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Morshedi, M. Cutting-edge nanotechnology: Unveiling the role of zinc oxide nanoparticles in combating deadly gastrointestinal tumors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1547757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigbe, U.O.; Osibote, O.A. Green synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles, and their various applications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, R.; Obeid, R.Z.; Abu-Huwaij, R. Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Kalegowda, N.; Gowtham, H.G.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alghamdi, S.; Shilpa, N.; Singh, S.B.; Thriveni, M.; Aiyaz, M. Plant-mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles: Advances in the new millennium towards understanding their therapeutic role in biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, G.M.; Iturbe-Ek, J.; Sustaita, A.O.; Melo-Maximo, D.V.; Bhatti, A.; Esparza-Sanchez, J.; Navarro-Lopez, D.E.; Lopez-Mena, E.R.; Sanchez-Lopez, A.L.; Lozano, L.M. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles from Natural Agave, Chiku, and Soursop Extracts: A Sustainable Approach to Antibacterial Applications. Crystals 2025, 15, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhujaily, M.; Albukhaty, S.; Yusuf, M.; Mohammed, M.K.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Al-Karagoly, H.; Alyamani, A.A.; Albaqami, J.; AlMalki, F.A. Recent advances in plant-mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles with their significant biomedical properties. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, H.U.R.; Khan, M.K.; Abbas, Z.; Riaz, R.; Abbas, R.Z.; Aleem, M.T.; Abbas, A.; Almutairi, M.M.; Alshammari, F.A.; Alraey, Y.J.L. Nanoparticles: Synthesis and their role as potential drug candidates for the treatment of parasitic diseases. Life 2022, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geioushy, R.A.; El-Sherbiny, S.; Mohamed, E.T.; Fouad, O.A.; Samir, M. Mechanical characteristics and antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus of sustainable cellulosic paper coated with Ag and Cu modified ZnO nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, G.H.; Shaly, A.A.; Ragu, R.; Evangelin, G.; Mani, J.; Martin, A.; Linet, J.M. ZnO nanoparticles with altered structural and optical traits by Cu and Li doping for elevated photocatalytic activity toward organic pollutants. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2024, 46, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, F.; Neri, G. Effect of Pb doping on the structural, optical and electrical properties of sol–gel ZnO nanoparticles. Discov. Mater. 2023, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Xiao, Z.; Luo, Y. Sustainable Nanotechnology for Food Preservation: Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Applications of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiouani, K.; Hegazy, S.; Alsaeedi, H.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Green Synthesis of Hexagonal-like ZnO nanoparticles modified with phytochemicals of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Thymus capitatus extracts: Enhanced antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities. Materials 2024, 17, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilavenil, K.; Senthilkumar, V.; Kasthuri, A. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles from three medicinal plants: A review of environmental and health applications. Discov. Catal. 2025, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ramos, D.I.; Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; García-Barradas, O.; Chacón-López, M.A.; Montalvo-González, E.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A.; Valenzuela-Vázquez, U.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Lauroylated, Acetylated, and Succinylated Agave tequilana Fructans Fractions: Structural Characterization, Prebiotic, Antibacterial Activity and Their Effect on Lactobacillus paracasei under Gastrointestinal Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.V.; Simpson, J.; Clench, M.R.; Gomez-Vargas, A.D.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J. Localization and Composition of Fructans in Stem and Rhizome of Agave tequilana Weber var. azul. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 608850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riwayati, I.; Winardi, S.; Madhania, S.; Shimada, M. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Cosmos caudatus: Effects of calcination temperature and precursor type on photocatalytic and antimicrobial activities. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Khan, M.A. Plant-derived metal nanoparticles (PDMNPs): Synthesis, characterization, and oxidative stress-mediated therapeutic actions. Future Pharmacol. 2023, 3, 252–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.; Mishra, D.; Sahoo, G. A review on green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Paul, D.R.; Sharma, A.; Choudhary, P.; Meena, P.; Nehra, S. Biogenic mediated Ag/ZnO nanocomposites for photocatalytic and antibacterial activities towards disinfection of water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 563, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Paul, D.R.; Sharma, A.; Hooda, D.; Yadav, R.; Meena, P.; Nehra, S.P. Phytoextract mediated ZnO/MgO nanocomposites for photocatalytic and antibacterial activities. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 385, 112049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Mascitti, A.; Rastelli, G.; d’Alessandro, N.; Tonucci, L. Sustainable Photocatalytic Reduction of Maleic Acid: Enhancing CuxO/ZnO Stability with Polydopamine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzarnezhad, F.; Allahdou, M.; Mehravaran, L.; Naderi, S. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles from the extract of Cymbopogon olivieri and investigation of their antimicrobial and anticancer effects. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Somaiah, S. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Thryallis glauca (Cav.) Kuntze and their role as antioxidant and antibacterial. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 2835–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanimozhi, S.; Durga, R.; Sabithasree, M.; Kumar, A.V.; Sofiavizhimalar, A.; Kadam, A.A.; Rajagopal, R.; Sathya, R.; Azelee, N.I.W. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticle using Cissus quadrangularis extract and its invitro study. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.; Aslam, U.; Khalid, B.; Chen, B. Green route to synthesize Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Cassia fistula and Melia azadarach and their antibacterial potential. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Abdallah, Y.; Ali, M.A.; Masum, M.M.I.; Li, B.; Sun, G.; Meng, Y.; Wang, Y.; An, Q. Lemon-fruit-based green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and titanium dioxide nanoparticles against soft rot bacterial pathogen Dickeya dadantii. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.S.; Sani, A.M.; Mohseni, S. Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles from leaf extract of Mentha pulegium (L.). Microb. Pathog. 2019, 131, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojkumar, U.; Kaliannan, D.; Srinivasan, V.; Balasubramanian, B.; Kamyab, H.; Mussa, Z.H.; Palaniyappan, J.; Mesbah, M.; Chelliapan, S.; Palaninaicker, S. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Brassica oleracea var. botrytis leaf extract: Photocatalytic, antimicrobial and larvicidal activity. Chemosphere 2023, 323, 138263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, H.; Venugopal, K.; Rajagopal, K.; De Britto, S.; Nandini, B.; Pushpalatha, H.G.; Konappa, N.; Udayashankar, A.C.; Geetha, N.; Jogaiah, S. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Eucalyptus globules and their fungicidal ability against pathogenic fungi of apple orchards. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, A.; Khatami, M.; Ebrahimy, O.; Sarani, M. Cytotoxic and antifungal studies of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using extract of Prosopis farcta fruit. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2020, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavithaa, K.; Paulpandi, M.; Ponraj, T.; Murugan, K.; Sumathi, S. Induction of intrinsic apoptotic pathway in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells through facile biosynthesized zinc oxide nanorods. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2016, 2, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamah, S.A.; Albukhaty, S.; Falih, I.Q.; Dewir, Y.H.; Mahood, H.B. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Capparis spinosa L. fruit extract: Characterization, biocompatibility, and antioxidant activity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efati, Z.; Shahangian, S.S.; Darroudi, M.; Amiri, H.; Hashemy, S.I.; Aghamaali, M.R. Green chemistry synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles in Lepidium sativum L. seed extract and evaluation of their anticancer activity in human colorectal cancer cells. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 32568–32576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, T.; Lokhande, R.; Khadke-Lokhande, L.; Chandorkar, J. Green synthesis, characterization, application and study of antimicrobial properties of zinc oxide nano particles using Cyathocline purpurea phytoextract. Pharma. Innov. 2023, 12, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.H.; Andia, J.D.; Manjunatha, S.; Murali, M.; Amruthesh, K.; Jagannath, S. Antimitotic and DNA-binding potential of biosynthesized ZnO-NPs from leaf extract of Justicia wynaadensis (Nees) Heyne-A medicinal herb. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101024. [Google Scholar]

- Kavya, J.; Murali, M.; Manjula, S.; Basavaraj, G.; Prathibha, M.; Jayaramu, S.; Amruthesh, K. Genotoxic and antibacterial nature of biofabricated zinc oxide nanoparticles from Sida rhombifolia Linn. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunchegowda, U.A.; Shivaram, A.B.; Mahadevamurthy, M.; Ramachndrappa, L.T.; Lalitha, S.G.; Krishnappa, H.K.N.; Anandan, S.; Sudarshana, B.S.; Chanappa, E.G.; Ramachandrappa, N.S. Biosynthesis of Zinc oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Passiflora subpeltata: Characterization and antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli isolated from poultry faeces. J. Clust. Sci. 2021, 32, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melk, M.M.; El-Hawary, S.S.; Melek, F.R.; Saleh, D.O.; Ali, O.M.; El Raey, M.A.; Selim, N.M. Nano zinc oxide green-synthesized from Plumbago auriculata lam. alcoholic extract. Plants 2021, 10, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awadh, A.A.; Shet, A.R.; Patil, L.R.; Shaikh, I.A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Nadaf, R.; Mahnashi, M.H.; Desai, S.V.; Muddapur, U.M.; Achappa, S. Sustainable synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Raphanus sativus extract and its biomedical applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Gunasangkaran, G.; Arumugam, V.A.; Muthukrishnan, S. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles of solanum nigrum and its anticancer activity via the induction of apoptosis in cervical cancer. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2022, 200, 2684–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Vaseeharan, B.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Shobiya, M. Laurus nobilis leaf extract mediated green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles: Characterization and biomedical applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, M.; Varma, R.S.; Zafarnia, N.; Yaghoobi, H.; Sarani, M.; Kumar, V.G. Applications of green synthesized Ag, ZnO and Ag/ZnO nanoparticles for making clinical antimicrobial wound-healing bandages. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2018, 10, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, K.; Nazli, Z.-i.-H.; Munir, H.; Aslam, M.; Khalofah, A. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera leaf extract, probing antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, N.; Saha, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Maiti, M.; Das, S.; Basu, R.; Nandy, P. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Hibiscus subdariffa leaf extract: Effect of temperature on synthesis, anti-bacterial activity and anti-diabetic activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 4993–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregoso-Zamorano, B.E.; Mancilla-Villa, O.R.; Guevara-Gutiérrez, R.D.; Moreno-Hernández, A.; Figueroa-Bautista, P.; Can-Chulim, Á.; Hernández-Vargas, O.; Cruz-Crespo, E.; Ortega-Escobar, H.M.; Khalil Gardezi, A.J.T.L. Caracterización edafológica con cultivo de agave azul (Agave tequilana Weber) en Tonaya y Tuxcacuesco, Jalisco, México. Terra Latinoam. 2023, 41, e1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, D.; McCulligh, C.; Lucio, C. Distilling agro-extractivism: Agave and tequila production in Mexico. J. Agrar. Chang. 2021, 21, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, W.G.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Ochoa-Martínez, L.A.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, O.M.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; González-Herrera, S.M. Agave fructans: A review of their technological functionality and extraction processes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Chávez, J.; Villamiel, M.; Santos-Zea, L.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K. Agave by-products: An overview of their nutraceutical value, current applications, and processing methods. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 720–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Sohnius, E.-M.; Attig, R.; López, M.G. Quantification of selected volatile constituents and anions in Mexican Agave spirits (Tequila, Mezcal, Sotol, Bacanora). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3911–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhrani, M.A.; Tahira, A.; Bhatti, M.A.; Shah, A.A.; Shaikh, N.M.; Mari, R.H.; Vigolo, B.; Emo, M.; Albaqami, M.D.; Nafady, A. A green approach for the preparation of ZnO@C nanocomposite using agave americana plant extract with enhanced photodegradation. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 505202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, J.M.; Escalante, A.; Murillo-Vázquez, R.N.; Delgado, E.; González, F.J.; Toríz, G. Use of Agave tequilana-lignin and zinc oxide nanoparticles for skin photoprotection. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 163, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.; Tinel, L.; Gonzalez, L.; Ciuraru, R.; Bernard, F.; George, C.; Volkamer, R. UV photochemistry of carboxylic acids at the air-sea boundary: A relevant source of glyoxal and other oxygenated VOC in the marine atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, J.C.; Ducasse, M.A.; Cheynier, V. Ultraviolet spectroscopy study of phenolic substances and other major compounds in red wines: Relationship between astringency and the concentration of phenolic substances. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; LaRocca, C.A.; Bernat, J.D.; Lindsey, J.S. Digital database of absorption spectra of diverse flavonoids enables structural comparisons and quantitative evaluations. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1087–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsipur, M.; Roushani, M.; Pourmortazavi, S.M. Electrochemical synthesis and characterization of zinc oxalate nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.A.; Wissa, D.; Hassan, H.; Ebnalwaled, A.; Khairy, S. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using low-cost plant extracts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H. Ultraviolet detectors based on wide bandgap semiconductor nanowire: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.; Waheed, A.; Sharif, M.S.; Saleem, M.; Afreen, A.; Tariq, M.; Kamal, A.; Al-Onazi, W.A.; Al Farraj, D.A.; Ahmad, S. Green synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles from green algae and their assessment in various biological applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoohinkong, W.; Foophow, T.; Pecharapa, W. Synthesis and characterization of copper zinc oxide nanoparticles obtained via metathesis process. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Sharma, A.; Anand, K.; Panday, A.; Tagotra, S.; Kakran, S.; Singh, A.K.; Alam, M.W.; Kumar, S.; Bouzid, G. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using E. cardamomum and zinc nitrate precursor: A dual-functional material for water purification and antibacterial applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 16742–16765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.B.; Iftikhar, T.; Majeed, H. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for the industrial biofortification of (Pleurotus pulmonarius) mushrooms. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaba, M.H.; El-Sherbiny, G.M.; Ewais, E.A.; Darwesh, O.M.; Moghannem, S.A. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) by Streptomyces baarnensis and its active metabolite (Ka): A promising combination against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens and cytotoxicity. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, K.; Asif, M.; Farooq, U.; Gilani, S.J.; Bin Jumah, M.N.; Ahmed, M.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory applications of Aerva persica aqueous-root extract-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15882–15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Saied, E.; Eid, A.M.; Kouadri, F.; Alemam, A.M.; Hamza, M.F.; Alharbi, M.; Elkelish, A.; Hassan, S.E.-D. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using an aqueous extract of Punica granatum for antimicrobial and catalytic activity. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, M.; Kumar, S.; Gaur, J.; Kaushal, S.; Dalal, J.; Singh, G.; Misra, M.; Ahlawat, D.S. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Justicia adhatoda for photocatalytic degradation of malachite green and reduction of 4-nitrophenol. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 2958–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Ramírez, S.d.C.; Valle, E.-d.; Raymundo, J.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Ruíz-Luna, J.; Velasco-Velasco, V.A. Growth of Agave angustifolia Haw. In relation to its nutritional condition. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2021, 12, 865–873. [Google Scholar]

- Babayevska, N.; Przysiecka, Ł.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Nowaczyk, G.; Jarek, M.; Janiszewska, E.; Jurga, S. ZnO size and shape effect on antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity profile. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Habib, I.; Maatouk, H.; Lemarchand, A.; Dine, S.; Roynette, A.; Mielcarek, C.; Traoré, M.; Azouani, R. Antibacterial size effect of ZnO nanoparticles and their role as additives in emulsion waterborne paint. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irede, E.L.; Awoyemi, R.F.; Owolabi, B.; Aworinde, O.R.; Kajola, R.O.; Hazeez, A.; Raji, A.A.; Ganiyu, L.O.; Onukwuli, C.O.; Onivefu, A.P. Cutting-edge developments in zinc oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications for enhanced antimicrobial and UV protection in healthcare solutions. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 20992–21034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Chu, Y.; Guo, R.; Chen, P. Research on the antibacterial properties of nanoscale zinc oxide particles comprehensive review. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1449614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Natural Resources; Species Survival Commission. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |