Organokine-Mediated Crosstalk: A Systems Biology Perspective on the Pathogenesis of MASLD—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Exploring the Liver-Muscle Crosstalk (Hepatokines and Myokines) in MASLD

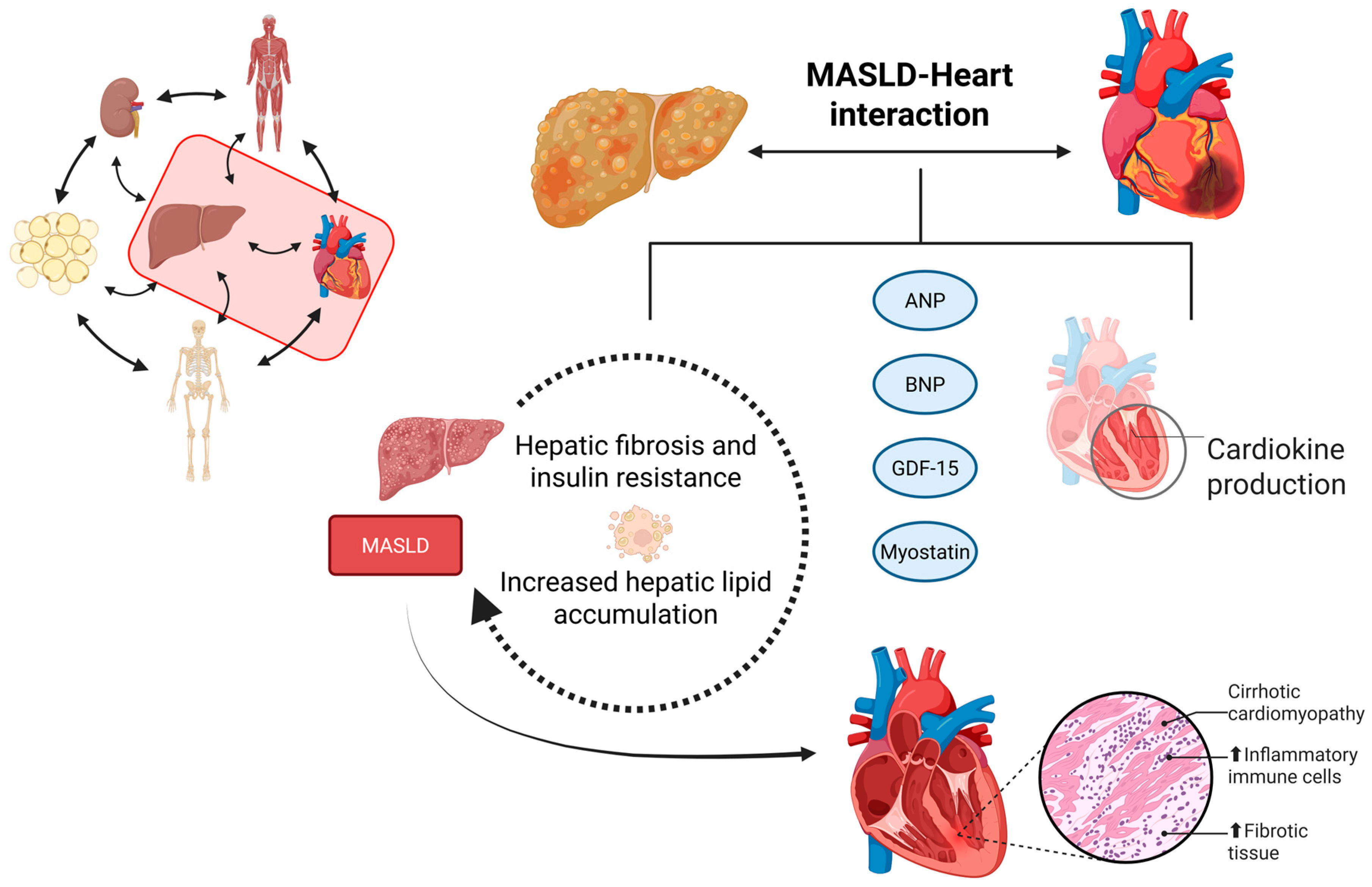

3. Exploring the Liver-Heart Crosstalk (Hepatokines and Cardiokines) in MASLD

4. Exploring the Liver-Kidney Crosstalk (Hepatokines and Renokines) in MASLD

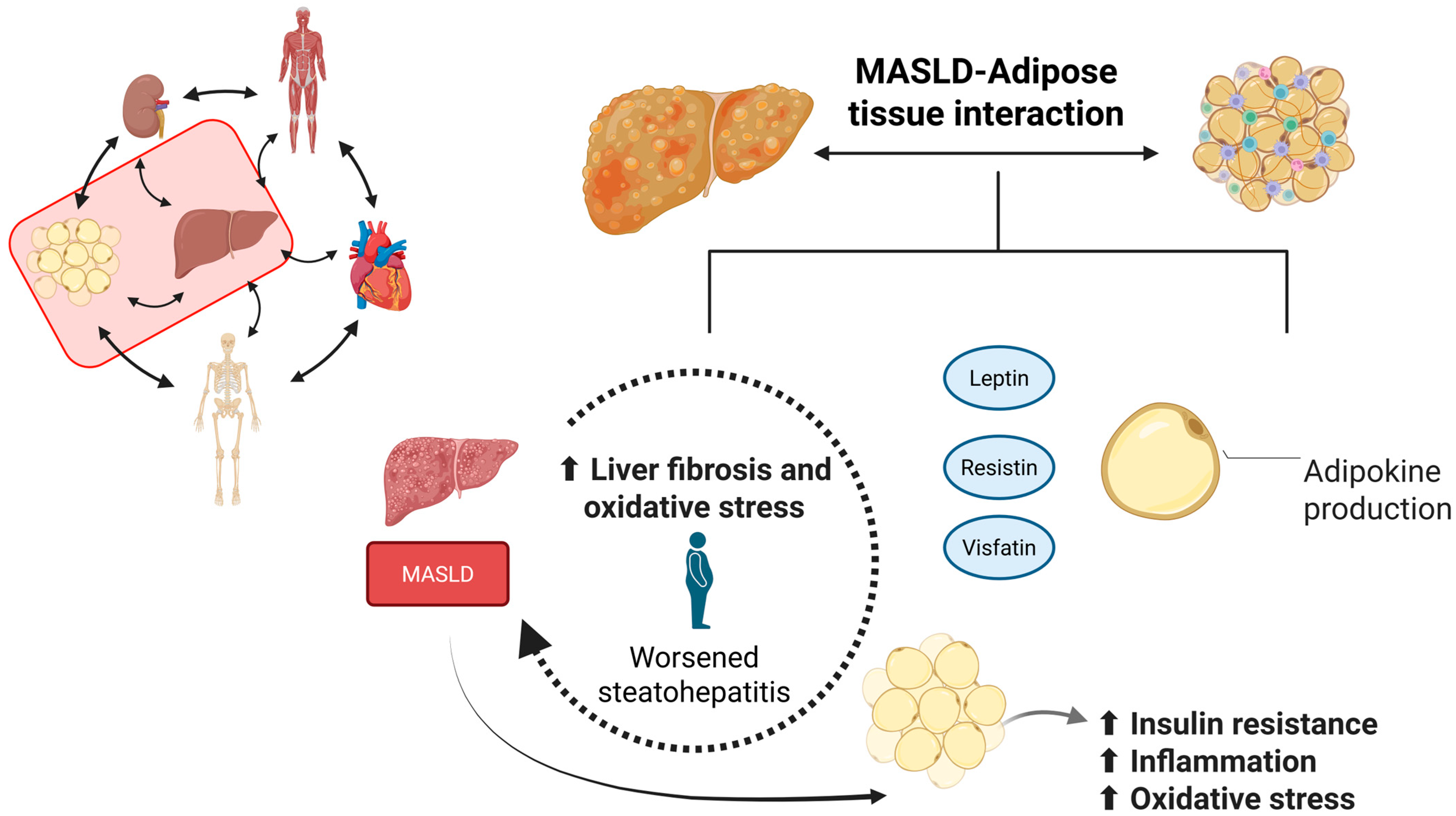

5. Exploring the Liver-Adipose Tissue Crosstalk (Hepatokines and Adipokines) in MASLD

6. Exploring the Liver-Bone Tissue Crosstalk (Hepatokines and Osteokines) in MASLD

7. Conclusions

8. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scope and Objectives | This narrative review aims to synthesize current evidence on the mechanisms of interorgan crosstalk in MASLD, with an emphasis on emerging mechanistic and therapeutic perspectives. |

| Search Strategy | PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink were searched. Keywords included “Organokines” and “MASLD”. No time restrictions were imposed. Inclusion comprised articles that delve into hepatokines, osteokines, renokines, myokines, cardiokines, and adipokines in the context of MASLD development and progression, as well as the interorgan crosstalk between the liver, bones, kidneys, muscles, heart, and adipose tissue producers in MASLD. |

| Data Extraction and Synthesis | The results were synthesized thematically, highlighting three main aspects: “Tissue-Derived Cytokine,” “Condition/Stimulus for Release,” and “Relations with MASLD.” |

References

- Zhang, J.Z.; Liu, C.H.; Shen, Y.L.; Song, X.N.; Tang, H.; Li, H. Sarcopenia in trauma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 104, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellen, R.H.; Girotto, O.S.; Marques, E.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Grippa, P.C.; Mendes, C.G.; Garcia, L.N.H.; Bechara, M.D.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sinatora, R.V.; et al. Insights into Pathogenesis, Nutritional and Drug Approach in Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Laurindo, L.F.; Cherain, L.M.A.; de Lima, E.P.; Boaro, B.L.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Chagas, E.F.B.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; et al. Targeting AMPK with Irisin: Implications for metabolic disorders, cardiovascular health, and inflammatory conditions—A systematic review. Life Sci. 2025, 360, 123230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direito, R.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sepodes, B.; Figueira, M.E. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Exploring Neuroprotective, Metabolic, and Hepatoprotective Effects for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Galicia, A.E.; Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Ponciano-Rodriguez, G.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Revolutionizing the understanding of liver disease: Metabolism, function and future. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.D.; Chen, Q.F.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Zhang, H.; Lonardo, A.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Porta, G.; Misra, A.; et al. Global burden of disease attributable to metabolic risk factors in adolescents and young adults aged 15–39, 1990–2021. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Baffy, G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Evolution of the final terminology. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 124, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q.; El-Serag, H.B.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Fornari Laurindo, L. AdipoRon and ADP355, adiponectin receptor agonists, in Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpi, R.Z.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sloan, K.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Gonzaga, H.F.; Grippa, P.C.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Girio, R.J.S.; Repetti, C.S.F.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. The Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Non-Alcoholic Fat Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, G.; Raggi, P.; Guaraldi, G. Integrating the care of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease into Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Multisystem Approach. Can. J. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddin, M.; Vipani, A.; Bresee, C.; Todo, T.; Kim, I.K.; Alkhouri, N.; Setiawan, V.W.; Tran, T.; Ayoub, W.S.; Lu, S.C. NASH leading cause of liver transplant in women: Updated analysis of indications for liver transplant and ethnic and gender variances. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol.|ACG 2018, 113, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanath, A.; Fouda, S.; Fernandez, C.J.; Pappachan, J.M. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and sarcopenia: A double whammy. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Kim, S.U.; Wong, V.W.; Valenti, L.; Glickman, M.; Ponce, J.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Crespo, J.; et al. A global survey on the use of the international classification of diseases codes for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 1178–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cól, J.P.; de Lima, E.P.; Pompeu, F.M.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Bechara, M.D.; Laurindo, L.F.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Barbalho, S.M. Underlying Mechanisms behind the Brain-Gut-Liver Axis and Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.F.; Varady, K.A.; Wang, X.D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tayyem, R.; Latella, G.; Bergheim, I.; Valenzuela, R.; George, J.; et al. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2024, 161, 156028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauil, R.B.; Golono, P.T.; de Lima, E.P.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Guiguer, E.L.; Bechara, M.D.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Yanaguizawa Junior, J.L.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; et al. Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: The Influence of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Mitochondrial Dysfunctions, and the Role of Polyphenols. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shoukrofy, M.S.; Ismail, A.; Elhamammy, R.H.; Abdelhady, S.A.; Nassra, R.; Makkar, M.S.; Agami, M.A.; Wahid, A.; Nematalla, H.A.; Sai, M.; et al. Novel thiazolones for the simultaneous modulation of PPARγ, COX-2 and 15-LOX to address metabolic disease-associated portal inflammation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 289, 117415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdul Razzak, I.; Fares, A.; Stine, J.G.; Trivedi, H.D. The Role of Exercise in Steatotic Liver Diseases: An Updated Perspective. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2025, 45, e16220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Jang, Y.; Choi, J.; Hur, J.; Kim, S.; Kwon, Y. New Insights into AMPK, as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Hepatic Fibrosis. Biomol. Ther. 2025, 33, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, Y.; Kubota, N.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T. Role of Insulin Resistance in MAFLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cang, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, J.; Zhu, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J.; Xu, C. Farrerol alleviates insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis of metabolic associated fatty liver disease by targeting PTPN1. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Moretti, R.C., Jr.; Torres Pomini, K.; Laurindo, L.F.; Sloan, K.P.; Sloan, L.A.; Castro, M.V.M.; Baldi, E., Jr.; Ferraz, B.F.R.; de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, E.; et al. Glycolipid Metabolic Disorders, Metainflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling Pathways. Biology 2024, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Mao, Y.; Cheung, T.T.; Yilmaz, Y.; Valenti, L.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Sookoian, S.; Chan, W.K.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of primary liver cancer attributable to metabolic risks: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 2280–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Loomba, R.; Ahmed, A. Current Burden of MASLD, MetALD, and Hepatic Fibrosis among US Adults with Prediabetes and Diabetes, 2017–2023. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 31, e235–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Razavi, H.; Sherman, M.; Allen, A.M.; Anstee, Q.M.; Cusi, K.; Friedman, S.L.; Lawitz, E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Schuppan, D.; et al. Addressing the High and Rising Global Burden of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH): From the Growing Prevalence to Payors’ Perspective. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 61, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsinikos, T.; Aw, M.M.; Bandsma, R.; Godoy, M.; Ibrahim, S.H.; Mann, J.P.; Memon, I.; Mohan, N.; Mouane, N.; Porta, G.; et al. FISPGHAN statement on the global public health impact of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2025, 80, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unalp-Arida, A.; Ruhl, C.E. Prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and fibrosis defined by liver elastography in the United States using National Health and Nutrition examination survey 2017-march 2020 and august 2021-august 2023 data. Hepatology 2025, 82, 1256–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Danpanichkul, P.; Agopian, V.; Mehta, N.; Parikh, N.D.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Singal, A.G.; Yang, J.D. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Updates on epidemiology, surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, S228–S254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, J.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, L.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Profiling of RNA N6-Methyladenosine methylation reveals the critical role of m6A in betaine alleviating hepatic steatosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri, N.; Charlton, M.; Gray, M.; Noureddin, M. The pleiotropic effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: A review for gastroenterologists. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2025, 34, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, H.; Liang, G.; Lin, Y.; Qian, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Systemic aging and aging-related diseases. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2025, 39, e70430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbaroğlu, B.F.; Balaban, Y.H.; Düger, T. Muscle Strength and Cardiovascular Health in MASLD: A Prospective Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Minniti, G.; Miola, V.F.B.; Haber, J.; Bueno, P.; de Argollo Haber, L.S.; Girio, R.S.J.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Dall’Antonia, C.T.; Rodrigues, V.D.; et al. Organokines in COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Cells 2023, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Maio, M.C.; Barbalho, S.M.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Flato, U.A.P.; Júnior, E.B.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; et al. Organokines in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Liu, J. Crosstalk between fat tissue and muscle, brain, liver, and heart in obesity: Cellular and molecular perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuta, M.; Masaki, T.; Kimura, S.; Sato, Y.; Tomida, A.; Ishikawa, I.; Nakamura, Y.; Takuma, K.; Nakahara, M.; Oura, K.; et al. Efficiency of Skeletal Muscle Mass/Weight Measurement for Distinguishing Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Prospective Analysis Using InBody Bioimpedance Devices. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real Martinez, Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, C.E.; Fuertes-Yebra, E.; Calvo Soto, M.; Berlana, A.; Barrios, V.; Caldas, M.; Gonzalez Moreno, L.; Garcia-Buey, L.; Molina Baena, B.; et al. Assessment of skeletal muscle alterations and circulating myokines in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A cross-sectional study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crişan, D.; Avram, L.; Morariu-Barb, A.; Grapa, C.; Hirişcau, I.; Crăciun, R.; Donca, V.; Nemeş, A. Sarcopenia in MASLD-Eat to Beat Steatosis, Move to Prove Strength. Nutrients 2025, 17, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, A.; Wang, Z.; Ni, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Chang, Y.; et al. Irisin alleviates hepatic steatosis by activating the autophagic SIRT3 pathway. Chin. Med. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faramia, J.; Ostinelli, G.; Drolet-Labelle, V.; Picard, F.; Tchernof, A. Metabolic adaptations after bariatric surgery: Adipokines, myokines and hepatokines. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 52, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayharman, S.; Belviranlı, M.; Okudan, N. The association between circulating irisin, osteocalcin and FGF21 levels with anthropometric characteristics and blood lipid profile in young obese male subjects. Adv. Med. Sci. 2025, 70, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Lima, E.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; Dias, J.A.; Barbosa Tavares Filho, M.; Zuccari, D.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Miglino, M.A.; Chagas, E.F.B.; et al. Targeting Muscle Regeneration with Small Extracellular Vesicles from Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells-A Review. Cells 2025, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gil, A.M.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L. The Role of Exercise in the Interplay between Myokines, Hepatokines, Osteokines, Adipokines, and Modulation of Inflammation for Energy Substrate Redistribution and Fat Mass Loss: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Miola, V.F.B.; Barbalho, S.M.; Santos Bueno, P.C.; Flato, U.A.P.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Buchaim, D.V.; Buchaim, R.L.; Tofano, R.J.; et al. Adipokines, Myokines, and Hepatokines: Crosstalk and Metabolic Repercussions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Wu, D.; Shi, H. Exercise and exerkines: Mechanisms and roles in anti-aging and disease prevention. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 200, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, W.; Herzog, R.W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.E.; Han, R. Liver-specific in vivo base editing of Angptl3 via AAV delivery efficiently lowers blood lipid levels in mice. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Cho, Y.; Son, S.M.; Hur, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Oh, H.; Lee, H.Y.; Jung, S.; Park, S.; Kim, I.Y.; et al. Activin E is a new guardian protecting against hepatic steatosis via inhibiting lipolysis in white adipose tissue. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Qi, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, W.; Fan, B.; Wu, H.; Ge, J. Fetuin-A increases thrombosis risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by binding to TLR-4 on platelets. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tanaka, S.; Kobayashi, R.; Murai, R.; Takahashi, S. Analytical and Clinical Validation of a Plasma Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 ELISA Kit Using an Automated Platform in Steatotic Liver Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Toyama, T.; Taguchi, K.; Arisawa, K.; Kaneko, T.; Tsutsumi, R.; Yamamoto, M.; Saito, Y. Sulforaphane decreases serum selenoprotein P levels through enhancement of lysosomal degradation independent of Nrf2. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimura-Shimizu, M.; Kurrey, K.; Miyata, M.; Dezawa, T.; Tsuneyama, K.; Kojima, M. Emerging Insights into the Role of BDNF on Health and Disease in Periphery. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Kim, S.K.; Asai, A. The role of Myokines in liver diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, I.; Kamimura, K.; Owaki, T.; Ko, M.; Nagoya, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohkoshi, M.; Setsu, T.; Sakamaki, A.; Yokoo, T. Complementary role of peripheral and central autonomic nervous system on insulin-like growth factor-1 activation to prevent fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 155–167, Correction in Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Yang, M.; Chen, H.; He, C.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Zhuo, J.; Lin, Z.; Hu, Z.; Lu, D. FGF21-mediated autophagy: Remodeling the homeostasis in response to stress in liver diseases. Genes. Dis. 2024, 11, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndakotsu, A.; Nduka, T.C.; Agrawal, S.; Asuka, E. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: Comprehensive insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Heart Fail. Rev. 2025, 30, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciałowicz, M.; Woźniewski, M.; Murawska-Ciałowicz, E.; Dzięgiel, P. The Influence of Irisin on Selected Organs-The Liver, Kidneys, and Lungs: The Role of Physical Exercise. Cells 2025, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringleb, M.; Javelle, F.; Haunhorst, S.; Bloch, W.; Fennen, L.; Baumgart, S.; Drube, S.; Reuken, P.A.; Pletz, M.W.; Wagner, H. Beyond muscles: Investigating immunoregulatory myokines in acute resistance exercise–A systematic review and meta-analysis. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1379–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taru, V.; Szabo, G.; Mehal, W.; Reiberger, T. Inflammasomes in chronic liver disease: Hepatic injury, fibrosis progression and systemic inflammation. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepero-Donates, Y.; Lacraz, G.; Ghobadi, F.; Rakotoarivelo, V.; Orkhis, S.; Mayhue, M.; Chen, Y.G.; Rola-Pleszczynski, M.; Menendez, A.; Ilangumaran, S.; et al. Interleukin-15-mediated inflammation promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cytokine 2016, 82, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheptulina, A.F.; Mamutova, E.M.; Elkina, A.Y.; Timofeev, Y.S.; Metelskaya, V.A.; Kiselev, A.R.; Drapkina, O.M. Serum irisin, myostatin, and myonectin correlate with metabolic health markers, liver disease progression, and blood pressure in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and hypertension. Metabolites 2024, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanigawa, R.; Nakajima, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Loomba, R.; Suganami, H.; Tanahashi, M.; Arai, H. Effects of Pemafibrate on Serum Carnitine and Plasma Myostatin in Patients With Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. JCSM Commun. 2025, 8, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, W.; Wang, M.; Zhou, T.; Liu, M.; Wu, Q.; Dong, N. Cardiac corin and atrial natriuretic peptide regulate liver glycogen metabolism and glucose homeostasis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakae, H.; Tanoue, S.; Mawatari, S.; Oda, K.; Taniyama, O.; Toyodome, A.; Ijuin, S.; Tabu, K.; Kumagai, K.; Ido, A. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: Predictors of Elevated Liver Stiffness and the Role of Transient Elastography in Long-Term Follow-Up. Cureus 2025, 17, e85336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risteska, M.; Vladimirova-Kitova, L.; Andonov, V. Serum NT-ProBNP potential marker of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Folia Med. 2022, 64, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Braghini, M.R.; Andolina, G.; De Stefanis, C.; Cesarini, L.; Pastore, A.; Comparcola, D.; Monti, L.; Francalanci, P.; Balsano, C.; et al. Levels of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 Correlated with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Children. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, P.; Pike, F.; Gawrieh, S.; Corey, K.E.; Hartig, S.; Balasubramanyam, A.; Ailstock, K.; Funderburg, N.; Lake, J.E. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 and growth differentiation factor 15 are associated with severity of hepatic steatosis in people with HIV. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, D.; Huang, J.; Bae, A.N.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, X.; Mortaja, M.; Azin, M.; Collier, M.R.; Semenov, Y.R.; et al. Hepatitis B virus promotes liver cancer by modulating the immune response to environmental carcinogens. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucarey, J.L.; Trujillo-González, I.; Paules, E.M.; Espinosa, A. Myokines and Their Potential Protective Role Against Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, O.O.; da Silva, A.A.; Li, X.; Taylor, L.C.; Greer, J.R.; Wasson, A.R.; McGowan, K.E.; Patel, P.R.; Stec, D.E. Cardiac lipotoxicity and fibrosis underlie impaired contractility in a mouse model of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. FASEB Bioadv. 2024, 6, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Perez-Bonilla, P.; Chen, X.; Tam, K.; Marshall, M.; Morin, J.; LaViolette, B.; Kue, N.R.; Damilano, F.; Miller, R.A.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Male Mouse With Adeno-Associated Viral Renin as a Novel Model for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e035894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Maric, D.; Idriss, S.; Delamare, M.; Le Roy, A.; Maaziz, N.; Caillaud, A.; Si-Tayeb, K.; Robriquet, F.; Lenglet, M.; et al. Identification of Hepatic-like EPO as a Cause of Polycythemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1684–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Ge, Z.; Meng, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Tang, S.; Lu, J.; Gu, T.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Erythropoietin alleviates hepatic steatosis by activating SIRT1-mediated autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Luo, X.; Chen, Q. Higher Circulating Alpha-klotho Levels Increase All-cause Mortality Through Mediation Effects of Liver Fibrosis: A Second Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glaf109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, M.; Dongiovanni, P.; Tiano, F.; Piciotti, R.; Alisi, A.; Panera, N. β-Klotho as novel therapeutic target in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A narrative review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Cunningham, T.; Yates, A.R.; Phelps, C.; Zepeda-Orozco, D.; Beckman, B.; Kistler, I.; Alexander, R.; Krawczeski, C.D.; Bi, J. Identifying kidney injury via urinary biomarkers after the comprehensive stage II palliation and bidirectional Glenn procedure: A pilot study. Cardiol. Young 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Tsuchiya, A.; Mito, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Kawata, Y.; Tominaga, K.; Terai, S. Urinary NGAL in gastrointestinal diseases can be used as an indicator of early infection in addition to acute kidney injury marker. JGH Open 2024, 8, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Shabalala, S.; Mabasa, L.; Kotzé-Hörstmann, L.; Sangweni, N.; Ramharack, P.; Sharma, J.; Pheiffer, C.; Arowolo, A.; Sadie-Van Gijsen, H. Integrated profiling of adiponectin and cytokine signaling pathways in high-fat diet-induced MASLD reveals early markers of disease progression. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.C.; Cai, W.F.; Ni, Q.; Lin, S.X.; Jiang, C.P.; Yi, Y.K.; Liu, L.; Liu, Q.; Shen, C.Y. A New Perspective on Signaling Pathways and Structure-Activity Relationships of Natural Active Ingredients in Metabolic Crosstalk Between Liver and Brown Adipose Tissue: A Narrative Review. Phytother. Res. PTR 2025, 39, 3062–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, A.R.; Martins, V.V.P.; Cardoso, J.C.; Torezani-Sales, S.; Miranda, K.O.; Salgado, B.S.; Monteiro, L.N.; Nogueira, B.V.; Leopoldo, A.S.; Lima-Leopoldo, A.P. High-Fat Diet Induces MASLD and Adipose Tissue Changes in Obesity-Resistant Rats. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 59, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas-Ramírez, A.; Maroto-Serrat, C.; Sanus, F.; Micó-Carnero, M.; Rojano-Alfonso, C.; Cabrer, M.; Peralta, C. Regulation of Adiponectin and Resistin in Liver Transplantation Protects Grafts from Extended-Criteria Donors. Am. J. Pathol. 2025, 195, 494–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S.; Navari, M.; Shafiee, R.; Mahmoudi, T.; Rezamand, G.; Asadi, A.; Nobakht, H.; Dabiri, R.; Farahani, H.; Tabaeian, S.P. The rs1862513 promoter variant of resistin gene influences susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20231537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, K.; Ke, Y.; Chen, S.; He, R.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, C.; Li, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Association of circulating visfatin level and metabolic fatty liver disease: An updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine 2024, 103, e39613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.J.; Choi, S.E.; Lee, N.; Jeon, J.Y.; Han, S.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, H.J. Visfatin exacerbates hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a methionine-choline-deficient diet mouse model. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Shen, Y.; Ma, X.; Ying, L.; Peng, J.; Pan, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhou, J. The association of serum FGF23 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independent of vitamin D in type 2 diabetes patients. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 45, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Bao, Y. Serum Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Level and Liver Fat Content in MAFLD: A Community-Based Cohort. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 4135–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocker, M. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Paving the way to hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Mondockova, V.; Kovacova, V.; Babikova, M.; Zemanova, N.; Biro, R.; Penzes, N.; Omelka, R. Interrelationships among metabolic syndrome, bone-derived cytokines, and the most common metabolic syndrome-related diseases negatively affecting bone quality. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Peng, X.; Li, N.; Gou, L.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J.; Liang, H.; Ma, P.; Li, S.; et al. Emerging role of liver-bone axis in osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Transl. 2024, 48, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Niu, K.; Yang, Z.; Song, J.; Wei, D.; Zhang, R.; Tao, K. Osteopontin: An indispensable component in common liver, pancreatic, and biliary related disease. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, J.K.; Jakubowska-Pietkiewicz, E. Osteocalcin: Beyond Bones. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 39, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, D.; Han, Y.; Li, N.; Tao, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, S.; et al. The role of sclerostin in lipid and glucose metabolism disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 215, 115694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, G.S.; Li, Q.R.; Zhang, Z. Current approach to the diagnosis of sarcopenia in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1422663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Balntzi, V.; Gray, S.R.; Lara, J.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.P.; Rolland, Y.; Schneider, S.M.; et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.A.; Cruz-Jentoft, A. Sarcopenia definition, diagnosis and treatment: Consensus is growing. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, E.; Pinel, A.; Guillet, C.; Capel, F.; Pereira, B.; De Antonio, M.; Pouget, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Eglseer, D.; Topinkova, E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality Among Older People. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e243604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.R.; Lee, S.; Song, S.K. A Review of Sarcopenia Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Future Direction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2022, 37, e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, R.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, M. Blood biomarkers for sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goisser, S.; Kob, R.; Sieber, C.C.; Bauer, J.M. Diagnosis and therapy of sarcopenia-an update. Der Internist 2019, 60, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affourtit, C.; Carré, J.E. Mitochondrial involvement in sarcopenia. Acta Physiol. 2024, 240, e14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Gutierrez, G.E.; Martínez-Gómez, L.E.; Martínez-Armenta, C.; Pineda, C.; Martínez-Nava, G.A.; Lopez-Reyes, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Inflammation in Sarcopenia: Diagnosis and Therapeutic Update. Cells 2022, 11, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.J.; Guralnik, J.; Cawthon, P.; Appleby, J.; Landi, F.; Clarke, L.; Vellas, B.; Ferrucci, L.; Roubenoff, R. Sarcopenia: No consensus, no diagnostic criteria, and no approved indication-How did we get here? GeroScience 2024, 46, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D. Exerkines and Sarcopenia: Unveiling the Mechanism Behind Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Metabolites 2025, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, L. The relationship between sarcopenia and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease among the young and middle-aged populations. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musio, A.; Perazza, F.; Leoni, L.; Stefanini, B.; Dajti, E.; Menozzi, R.; Petroni, M.L.; Colecchia, A.; Ravaioli, F. Osteosarcopenia in NAFLD/MAFLD: An Underappreciated Clinical Problem in Chronic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.Y.; Zhang, K.; Huang, X.Y.; Yang, F.; Sun, S.Y. Muscle strength and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zuo, J.; Zeng, C.; Mamtawla, G.; Huang, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Liver-secreted FGF21 induces sarcopenia by inhibiting satellite cell myogenesis via klotho beta in decompensated cirrhosis. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Bates, E.A.; Kipp, Z.A.; Pauss, S.N.; Martinez, G.J.; Blair, C.A.; Hinds, T.D., Jr. Insulin receptor responsiveness governs TGFβ-induced hepatic stellate cell activation: Insulin resistance instigates liver fibrosis. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2025, 39, e70427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zeng, C.; Yu, B. White adipose tissue in metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2024, 48, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mincone, T.; Contreras-Briceño, F.; Espinosa-Ramírez, M.; García-Valdés, P.; López-Fuenzalida, A.; Riquelme, A.; Arab, J.P.; Cabrera, D.; Arrese, M.; Barrera, F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and sarcopenia: Pathophysiological connections and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 14, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ai, L. Downhill running and caloric restriction attenuate insulin resistance associated skeletal muscle atrophy via the promotion of M2-like macrophages through TRIB3-AKT pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 210, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, T.T.; Xie, H.A.; Hu, P.P.; Li, P. Experimental cell models of insulin resistance: Overview and appraisal. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1469565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Ji, X.; Wang, F. Association of triglyceride glucose-related obesity indices with sarcopenia among U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jun, H.S. Role of Myokines in Regulating Skeletal Muscle Mass and Function. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Maio, M.C.; Lemes, M.A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Haber, J.; Bechara, M.D.; Prado, P.S.D., Jr.; Rauen, E.C.; Costa, F.; Pereira, B.C.A.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and Organokines: What Is Now and What Will Be in the Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, G.; Pescinini-Salzedas, L.M.; Minniti, G.; Laurindo, L.F.; Barbalho, S.M.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Sloan, L.A.; Haber, R.S.A.; Araújo, A.C.; Quesada, K.; et al. Organokines, Sarcopenia, and Metabolic Repercussions: The Vicious Cycle and the Interplay with Exercise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Flato, U.A.P.; Tofano, R.J.; Goulart, R.A.; Guiguer, E.L.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Buchaim, D.V.; Araújo, A.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Reina, F.T.R.; et al. Physical Exercise and Myokines: Relationships with Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, K.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Filip, R. What Does Sarcopenia Have to Do with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease? Life 2023, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, S.; Jeeyavudeen, M.S.; Pappachan, J.M.; Jayanthi, V. Pathobiology of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 52, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kwak, M.S.; Yang, J.I.; Chung, S.J.; Yim, J.Y.; Yoon, J.W.; Chung, G.E. The relationship between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and low muscle mass in an asymptomatic Korean population. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2953–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Wang, J.; Lu, Q.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Q. Relationship between metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 68, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Javaid, S.; Malik, M.I.; Qureshi, S. Relationship between sarcopenia and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Vachliotis, I.D.; Mantzoros, C.S. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2023, 147, 155676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.P.; Almeida, L.S.; Neri, S.G.R.; Oliveira, J.S.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Ribeiro, H.S.; Lima, R.M. Prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with chronic kidney disease: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cao, Y.; Ji, G.; Zhang, L. Lean nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and sarcopenia. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1217249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Qi, X.; Abenavoli, L.; Barranco-Fragoso, B.; Barbalho, S.M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. NAFLD-MASLD-MAFLD continuum: A swinging pendulum? Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Yoshimura, T.; Ichikawa, T. Liver Disease-Related Sarcopenia: A Predictor of Poor Prognosis by Accelerating Hepatic Decompensation in Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Cureus 2023, 15, e49078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ye, X.; Pan, M.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, L. Impact of steatotic liver disease subtypes, sarcopenia, and fibrosis on all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A 15.7-year cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, L.; Li, W. Correlation of sarcopenia with progression of liver fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A study from two cohorts in China and the United States. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, R.; Nakajima, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Loomba, R.; Suganami, H.; Tanahashi, M.; Saito, A.; Iida, Y.; Yamashita, S. Effects of Pemafibrate on LDL-C and Related Lipid Markers in Patients with MASLD: A Sub-Analysis of the PEMA-FL Study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2025, 32, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.I.; Mahin, A.; Prasad, T.S.K.; Abhinand, C.S. Transcriptome Profiling and Viral-Human Interactome Insights Into HBV-Driven Oncogenic Alterations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 69, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor Duric, L.; Belčić, V.; Oberiter Korbar, A.; Ćurković, S.; Vujicic, B.; Gulin, T.; Muslim, J.; Gulin, M.; Grgurević, M.; Catic Cuti, E. The Role of SHBG as a Marker in Male Patients with Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: Insights into Metabolic and Hormonal Status. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Han, K.D.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, K.S.; Hong, S.; Park, J.H.; Park, C.Y. Association of temporal MASLD with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, J.; Hou, Z.; Yan, Q.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J. Association between the dietary index for gut microbiota and all-cause/cardiovascular mortality in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, T.; Gieseler, R.K.; Patsalis, P.C.; Canbay, A. Towards harnessing the value of organokine crosstalk to predict the risk for cardiovascular disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2022, 130, 155179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.C.; Abdelmalek, M.F. The Liver in Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. Clin. Liver Dis. 2025, 29, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, M. Photobiomodulation mediates endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contact and ameliorates lipotoxicity in MASLD via Mfn2 upregulation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2025, 270, 113209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; de Lima, E.P.; Leme Boaro, B.; Mendes Peloi, J.M.; Ferraroni Sanches, R.C.; Penteado Detregiachi, C.R.; José Tofano, R.; Angelica Miglino, M.; Sloan, K.P.; et al. Targeting Atherosclerosis via NEDD4L Signaling-A Review of the Current Literature. Biology 2025, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bril, F.; Elbert, A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and urinary system cancers: Mere coincidence or reason for concern? Metab. Clin. Exp. 2025, 162, 156066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.K.; Song, J.E.; Loomba, R.; Park, S.Y.; Tak, W.Y.; Kweon, Y.O.; Lee, Y.R.; Park, J.G. Comparative associations of MASLD and MAFLD with the presence and severity of coronary artery calcification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri Lankarani, K.; Jamalinia, M.; Zare, F.; Heydari, S.T.; Ardekani, A.; Lonardo, A. Liver-Kidney-Metabolic Health, Sex, and Menopause Impact Total Scores and Monovessel vs. Multivessel Coronary Artery Calcification. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 1729–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandireddy, R.; Sakthivel, S.; Gupta, P.; Behari, J.; Tripathi, M.; Singh, B.K. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1433857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Bertolini, L.; Poli, F.; Rodella, S.; Scala, L.; Tessari, R.; Zenari, L.; Falezza, G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of future cardiovascular events among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2005, 54, 3541–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, C.; Ballestri, S.; Ricci, F.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Ticinesi, A.; Gallina, S.; Giamberardino, M.A.; Cipollone, F.; Sutton, R.; Vettor, R. Cardiovascular risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.G.; Roelstraete, B.; Khalili, H.; Hagström, H.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Mortality in biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from a nationwide cohort. Gut 2021, 70, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, F.; Vacca, A.; Bidault, G.; Sarver, D.; Kaminska, D.; Strocchi, S.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Greco, C.M.; Lusis, A.J.; Schiattarella, G.G. Decoding the Liver-Heart Axis in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1335–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Gan, J.; Zhou, X.; Tian, H.; Pan, X.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Du, J.; Xu, A.; Zheng, M. Myocardial infarction accelerates the progression of MASH by triggering immunoinflammatory response and induction of periostin. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1269–1286.e1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-Y.; Du, L.-J.; Shi, X.-R.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Chen, B.-Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y. An IL-6/STAT3/MR/FGF21 axis mediates heart-liver cross-talk after myocardial infarction. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Halawany, K.W.; Alyahyawi, F.S.; Khormi, A.H.; AlQibti, H.M.; Saifain, O.M.; Alqarni, T.M.; Alqurashi, J.S.; Alabdali, R.M.; Alowaimer, S.T. Effect of Blood Pressure Control on Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e86230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, O.; Giuliani, S.; Ferrero-Fernández, A.; Casciato, P.; Musso, C.G. Kidney–liver pathophysiological crosstalk: Its characteristics and importance. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 2203–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.; Nguyen, C.M.; Ruiz-Orera, J.; Mills, N.L.; Snyder, M.P.; Jang, C.; Shah, S.H.; Hübner, N.; Seldin, M. Emerging Technologies and Future Directions in Interorgan Crosstalk Cardiometabolic Research. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Y.R.; El-Hagrassi, A.M.; Nasr, N.N.; Abdallah, W.E.; Hamed, M.A. Chemical Composition and Therapeutic Potential of Syngonium podophyllum L. Leaves against Hypercholesterolemia in Rats: Liver, Kidney, and Heart Crosstalk. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2024, 20, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, N.K.; Heydari, Z.; Tamimi, A.H.; Zahmatkesh, E.; Shpichka, A.; Barekat, M.; Timashev, P.; Hossein-Khannazer, N.; Hassan, M.; Vosough, M. Review on kidney-liver crosstalk: Pathophysiology of their disorders. Cell J. 2024, 26, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Siebel, S.; Zhang, C.; Costa Lima, B.G.; Li, X. GDF15 is a critical renostat in the defense against hypoglycemia. Biorxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitupu, A.; Pratiwi, L.; Sutanto, H.; Santoso, D.; Hertanto, D.M. Molecular pathophysiology of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder: Focus on the fibroblast growth factor 23–Klotho axis and bone turnover dynamics. Exp. Physiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atić, A.; Gulin, M.; Hudolin, T.; Mokos, I.; Kaštelan, Ž.; Ćorić, M.; Bašić-Jukić, N. Association of the Expression of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Subtypes in Recipient Epigastric Arteries and Long-Term Outcomes After Kidney Transplantation. Turk. J. Nephrol. 2025, 34, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-H.; Pan, S.-Y.; Shih, H.-M.; Lin, S.-L. Update of pericytes function and their roles in kidney diseases. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2024, 123, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, R.F.; Pérez, R.G.; González, A.L. Beneficial effects of physical exercise on the osteo-renal Klotho-FGF-23 axis in Chronic Kidney Disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 21, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskapan, H.; Mahdavi, S.; Bellasi, A.; Martin, S.; Kuvadia, S.; Patel, A.; Taskapan, B.; Tam, P.; Sikaneta, T. Ethnic and seasonal variations in FGF-23 and markers of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Wei, X.; Guo, M.; Wu, W.; Ding, X. Clinical value of serum Klotho protein in patients with acute traumatic brain injury complicated by acute kidney injury. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Li, S.; Song, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, T. Association between the serum Klotho levels and diabetic kidney disease: Results from the NHANES 2007-2016 and Mendelian randomization study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, M.; Chen, Z.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Di, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Tang, R. Lipocalin-2 promotes CKD vascular calcification by aggravating VSMCs ferroptosis through NCOA4/FTH1-mediated ferritinophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bingül, İ.; Kalayci, R.; Tekkeşin, M.S.; Olgac, V.; Bekpinar, S.; Uysal, M. Chenodeoxycholic acid alleviated the cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity by decreasing oxidative stress and suppressing renin-angiotensin system through AT2R and ACE2 mRNA upregulation in rats. J. Mol. Histol. 2025, 56, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.-E.; Hsu, W.-T.; Hsiao, F.-Y.; Lee, C.-M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, renin-angiotensin system blockade or diuretics and risk of acute kidney injury: A case-crossover study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 123, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrache, A.; Micheau, O. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand: Non-apoptotic signalling. Cells 2024, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Crowley, S.D. hypertension. Renal effects of cytokines in hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 27, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Momper, J.D.; Nigam, S.K. Developmental regulation of kidney and liver solute carrier and ATP-binding cassette drug transporters and drug metabolizing enzymes: The role of remote organ communication. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Ahmad, S.F.; Al-Harbi, N.O.; Ibrahim, K.E.; Sarawi, W.; Attia, S.M.; Alasmari, A.F.; Alqarni, S.A.; Alfradan, A.S.; Bakheet, S.A.; et al. Role of ITK signaling in acute kidney injury in mice: Amelioration of acute kidney injury associated clinical parameters and attenuation of inflammatory transcription factor signaling in CD4+ T cells by ITK inhibition. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi Yarijani, Z.; Najafi, H. Effects of Peptides and Bioactive Peptides on Acute Kidney Injury: A Review Study. Iran. Biomed. J. 2025, 29, 90–103. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12394725/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Peng, W.X.; Li, Y.F.; Lu, P.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.G. GATA1 Transcriptionally Upregulates LMCD1, Promoting Ferroptosis in Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury Through the Hippo/YAP Pathway. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2025, 41, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katopodis, P.; Pappas, E.M.; Katopodis, K.P. Acid-base abnormalities and liver dysfunction. Ann. Hepatol. 2022, 27, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejong, C.; Deutz, N.; Soeters, P. Ammonia and glutamine metabolism during liver insufficiency: The role of kidney and brain in interorgan nitrogen exchange. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 31, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballmer, P.; McNurlan, M.; Hulter, H.; Anderson, S.E.; Garlick, P.; Krapf, R. Chronic metabolic acidosis decreases albumin synthesis and induces negative nitrogen balance in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HoleČek, M.; Šafránek, R.; Ryšavá, R.; KadlČíková, J.; Šprongl, L. Acute effects of acidosis on protein and amino acid metabolism in perfused rat liver. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2003, 84, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoste, E.; De Corte, W. Clinical consequences of acute kidney injury. Contrib. Nephrol. 2011, 174, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Patidar, K.R.; Naved, M.A.; Grama, A.; Adibuzzaman, M.; Ali, A.A.; Slaven, J.E.; Desai, A.P.; Ghabril, M.S.; Nephew, L.; Chalasani, N. Acute kidney disease is common and associated with poor outcomes in patients with cirrhosis and acute kidney injury. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, M.; Rosi, S.; Gambino, C.G.; Piano, S.; Calvino, V.; Romano, A.; Martini, A.; Pontisso, P.; Angeli, P. Natural history of acute kidney disease in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazory, A.; Ronco, C. Hepatorenal syndrome or hepatocardiorenal syndrome: Revisiting basic concepts in view of emerging data. Cardiorenal Med. 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Diehl, V.; Trebicka, J.; Wygrecka, M.; Schaefer, L. Biglycan: A regulator of hepatorenal inflammation and autophagy. Matrix. Biol. 2021, 100–101, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fede, G.; Privitera, G.; Tomaselli, T.; Spadaro, L.; Purrello, F. Cardiovascular dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann. Gastroenterol. Q. Publ. Hell. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Chahal, D.; Liu, H.; Shamatutu, C.; Sidhu, H.; Lee, S.S.; Marquez, V. comprehensive analysis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.S.; Choi, K.M. Organokines in disease. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2020, 94, 261–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianopoulos, I.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Daskalopoulou, S.S. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in atherosclerosis. Endocr. Rev. 2025, 46, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashandy, S.A.; Elbaset, M.A.; Ibrahim, F.A.; Abdelrahman, S.S.; Moussa, S.A.A.; El-Seidy, A.M. Management of cardiovascular disease by cerium oxide nanoparticles via alleviating oxidative stress and adipokine abnormalities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadgaonkar, U. The Interplay Between Adipokines and Body Composition in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbaghi, O.; Kelishadi, M.R.; Larky, D.A.; Bagheri, R.; Amirani, N.; Goudarzi, K.; Kargar, F.; Ghanavati, M.; Zamani, M. The effects of green tea extract supplementation on body composition, obesity-related hormones and oxidative stress markers: A grade-assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 1125–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, H.; Ding, W.; Yu, X.; Hou, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Adipokines regulate the development and progression of MASLD through organellar oxidative stress. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Meshkini, F.; Torabinasab, K.; Razmpoosh, E.; Toupchian, O.; Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Hemmati, A.; Sadat Sangsefidi, Z.; Abdollahi, S. Low fat-diet and circulating adipokines concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Ianiro, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Adolph, T.E. Adipokines: Masterminds of metabolic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.; Charrouf, R.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Hutchison, A.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R. The effects of time-restricted eating versus habitual diet on inflammatory cytokines and adipokines in the general adult population: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Bing, C.; Griffiths, H.R. Disrupted adipokine secretion and inflammatory responses in human adipocyte hypertrophy. Adipocyte 2025, 14, 2485927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duwaerts, C.C.; Maher, J.J. Macronutrients and the adipose-liver axis in obesity and fatty liver. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Uña, M.; López-Mancheño, Y.; Diéguez, C.; Fernández-Rojo, M.A.; Novelle, M.G. Unraveling the role of leptin in liver function and its relationship with liver diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-Color, L.; Dominguez-Rosales, J.A.; Maldonado-González, M.; Ruíz-Madrigal, B.; Sánchez Muñoz, M.P.; Zaragoza-Guerra, V.A.; Espinoza-Padilla, V.H.; Ruelas-Cinco, E.d.C.; Ramírez-Meza, S.M.; Torres Baranda, J.R. Evidence that peripheral leptin resistance in omental adipose tissue and liver correlates with MASLD in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Kwon, Y.; Joo, J.Y.; Kim, D.G.; Yoon, J.H. Secretomics to Discover Regulators in Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Ronaldo, R.; Kweon, B.-N.; Yoon, S.; Park, Y.; Baek, J.-H.; Lee, J.M.; Hyun, C.-K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Attenuate Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Diet-Induced Obese Mice by Activating the FGF21-Adiponectin Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorenza, M.; Checa, A.; Sandsdal, R.M.; Jensen, S.B.; Juhl, C.R.; Noer, M.H.; Bogh, N.P.; Lundgren, J.R.; Janus, C.; Stallknecht, B.M. Weight-loss maintenance is accompanied by interconnected alterations in circulating FGF21-adiponectin-leptin and bioactive sphingolipids. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashad, N.; Gameil, D.; Sakr, M.M.H.; Ahmed, S.; Mohammad, L.G.; Elsayed, A.M.; Shaker, G.E. Altered retinol binding protein-4 (RBP-4) mRNA in obesity is associated with the susceptibility and progression of Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Zagazig Univ. Med. J. 2024, 30, 5140–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Hu, J. Retinol binding protein 4 and type 2 diabetes: From insulin resistance to pancreatic β-cell function. Endocrine 2024, 85, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, R.; Liu, L. The role of adiponectin and its receptor signaling in ocular inflammation-associated diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 717, 150041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-M.; Kim, J.; Kim, B.-K.; Seo, H.J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-E.; Lee, J.; You, J.; Jin, S.; Kwon, Y.-W. Resistin regulates inflammation and insulin resistance in humans via the endocannabinoid system. Research 2024, 7, 0326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileva, E.; Stankova, T.; Batalov, K.; Staynova, R.; Nonchev, B.; Bivolarska, A.; Karalilova, R. Association of serum and synovial adipokines (chemerin and resistin) with inflammatory markers and ultrasonographic evaluation scores in patients with knee joint osteoarthritis-a pilot study. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francesca, M. Pathways Involved in Inflammaging and Frailty: The Paradigm of Visfatin in Inflammation and Metabolic Diseases and the Factors Influencing the Response to COVID-19 Vaccines. 2025. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/188902 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Varra, F.-N.; Varras, M.; Varra, V.-K.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation-mediating treatment options. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweesap, P.; Potue, P.; Khamseekaew, J.; Iampanichakul, M.; Jan, O.B.; Pakdeechote, P.; Maneesai, P. Luteolin Relieves Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Caused by a High-Fat Diet in Rats Through Modulating the AdipoR1/AMPK/PPARγ Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaedi, H.Z.R.; Dashti, N.; Fadaei, R.; Moradi, N.; Naeini, F.B.; Afrisham, R. WISP3/CCN6 Adipocytokine Marker in Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and its Association with Some Risk Factors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosialou, I.; Shikhel, S.; Liu, J.M.; Maurizi, A.; Luo, N.; He, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zong, H.; Friedman, R.A.; Barasch, J.; et al. MC4R-dependent suppression of appetite by bone-derived lipocalin 2. Nature 2017, 543, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Ren, J.-Y.; Huang, Y.-F.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Bai, Z.-R.; Leng, Y.; Tian, J.-W.; Wei, J.; Jin, M.-L.; Wang, G. Resistin upregulates fatty acid oxidation in synoviocytes of metabolic syndrome-associated knee osteoarthritis via CAP1/PKA/CREB to promote inflammation and catabolism. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2025, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafakhi, I.A.; Abdalsada, N.H. The association between retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) and peripheral neuropathy in type-II diabetic patients. Anaesth. Pain Intensive Care 2024, 28, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhong, G.; Jin, T.; Hu, W.; Wang, J.; Shi, B.; Wei, R. Diagnostic value of retinol-binding protein 4 in diabetic nephropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1356131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. Adiponectin resistance in obesity: Adiponectin leptin/insulin interaction. Obes. Lipotoxicity 2024, 431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Elgohary, M.N.; Bassiony, M.A.; Abdulsaboor, A.; Alsharqawy, A.-h.M.; Gad, S.A. Serum Resistin Level as A Biomarker in the Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Patients. Zagazig Univ. Med. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, Y.; Hong, C.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Cui, H.; Ma, P.; Li, R.; He, J. Association between fatty liver index and controlled attenuation parameters as markers of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and bone mineral density: Observational and two-sample Mendelian randomization studies. Osteoporos. Int. 2024, 35, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Anastasilakis, A.D.; Rafailidis, V.; Polyzos, S.A. Osteokines in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimonty, A.; Bonewald, L.F.; Huot, J.R. Metabolic health and disease: A role of osteokines? Calcif. Tissue Int. 2023, 113, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondrogianni, M.E.; Kyrou, I.; Androutsakos, T.; Flessa, C.-M.; Menenakos, E.; Chatha, K.K.; Aranan, Y.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Kassi, E.; Randeva, H.S. Anti-osteoporotic treatments in the era of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Friend or foe. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1344376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, F.; Perazza, F.; Leoni, L.; Stefanini, B.; Ferri, S.; Tovoli, F.; Zavatta, G.; Piscaglia, F.; Petroni, M.L.; Ravaioli, F. RANK–RANKL–OPG axis in MASLD: Current evidence linking bone and liver diseases and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, X.; Zou, X.; Jiang, S. Osteocalcin reduces fat accumulation and inflammatory reaction by inhibiting ROS-JNK signal pathway in chicken embryonic hepatocytes. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dong, K.; Du, Q.; Xu, J.; Bai, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. Chemically synthesized osteocalcin alleviates NAFLD via the AMPK-FOXO1/BCL6-CD36 pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zou, X.; Zhang, M.; Hu, H.; Wei, X.; Jin, M.; Cheng, H.-W.; Jiang, S. Osteocalcin prevents insulin resistance, hepatic inflammation, and activates autophagy associated with high-fat diet–induced fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome in aged laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad Rahimi, G.R.; Niyazi, A.; Alaee, S. The effect of exercise training on osteocalcin, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos. Int. 2021, 32, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Jin, C.H.; Ke, J.F.; Wang, J.W.; Ma, Y.L.; Lu, J.X.; Li, M.F.; Li, L.X. Decreased Serum Osteocalcin is an Independent Risk Factor for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 3717–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Liang, Y.; Li, H.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, K.; Li, W.; Feng, L.; et al. Associations between multiple metabolic biomarkers with steatotic liver disease subcategories: A 5-year Chinese cohort study. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, J.D.; Manka, P.P.; Swiderska-Syn, M.; Vannan, D.T.; Riva, A.; Claridge, L.C.; Moylan, C.; Suzuki, A.; Briones-Orta, M.A.; Younis, R.; et al. Osteopontin Promotes Cholangiocyte Secretion of Chemokines to Support Macrophage Recruitment and Fibrosis in MASH. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2025, 45, e16131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, K.; Heyerick, L.; De Ponti, F.F.; Vanderborght, B.; Meese, T.; Van Campenhout, S.; Baudonck, L.; Gijbels, E.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Banales, J.M.; et al. Osteopontin characterizes bile duct-associated macrophages and correlates with liver fibrosis severity in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2024, 79, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Tian, G.; Xin, X.; Qin, Y.; Feng, X. Metabolic disorders, inter-organ crosstalk, and inflammation in the progression of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Life Sci. 2024, 359, 123211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jin, Q.; Xiao, D.; Li, X.; Huang, D. Interaction mechanism and intervention strategy between metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and intestinal microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1597995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.R.; Direito, R.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Rubira, C.J.; Catharin, V.; Sloan, K.P.; Sloan, L.A.; Junior, J.L.Y.; et al. Bridging the Gut Microbiota and the Brain, Kidney, and Cardiovascular Health: The Role of Probiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borozan, S.; Fernandez, C.J.; Samee, A.; Pappachan, J.M. Gut-Adipose Tissue Axis and Metabolic Health. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tissue-Derived Cytokine | Condition/Stimulus for Release | Relations with MASLD | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatokines | |||

| ANGPTL3 | Liver lipid overload | Impairs lipid clearance; associated with dyslipidemia and liver fat | [48] |

| Activin E | ↑ in obesity and MASLD | Regulatory molecule that prevents fatty acid influx into the liver | [49] |

| Fetuin-A | Liver stress and insulin resistance | Promotes insulin resistance and hepatic lipid accumulation | [50] |

| FGF-21 | Fasting and metabolic stress | Enhances fatty acid oxidation; protective role in NAFLD | [51] |

| Selenoprotein P | Oxidative stress and liver dysfunction | Induces insulin resistance and hepatic inflammation | [52] |

| Myokines | |||

| BDNF | ↑ hepatic lipid oxidation | Regulates satiety; deficiency is associated with hyperphagia and ↑ hepatic fat deposition | [53,54,55] |

| FGF-21 (muscle-derived) | Metabolic stress and fasting | Improves lipid metabolism; protective in MASLD | [56] |

| Irisin | Physical exercise | Improves insulin sensitivity; reduces hepatic steatosis and inflammation | [57,58] |

| IL-6 (from muscle) | Acute exercise and chronic inflammation | Dual role: acute exercise-induced IL-6 is protective; chronically elevated levels may worsen hepatic inflammation | [59,60] |

| IL-15 | Elevated serum levels in obesity; ↑ in NASH, it recruits NK lymphocytes to the liver (excess aggravates inflammation) | This process increases hepatic lipid accumulation and modulates macrophage infiltration in the liver | [61,62] |

| Myostatin | Muscle inactivity; metabolic disorders | This condition hinders muscle growth and is linked to insulin resistance and the accumulation of liver fat | [63,64] |

| Cardiokines | |||

| ANP | Effective hypervolemia and atrial distension | Regulates liver glycogen metabolism and glucose homeostasis | [65] |

| BNP | Cardiac damage, acute myocardial infarction, and subclinical cardiac dysfunction in cirrhosis | Biomarker of volume overload and ↑ in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy | [66,67] |

| GDF-15 | Tissue injury and oxidative stress | Linked to metabolic regulation and hepatic stress adaptation | [68,69] |

| IL-33 | Cardiac stress and inflammation | May reduce liver inflammation and fibrosis in the early stages | [70] |

| Myostatin | Adipose tissue and muscle produce myostatin and worsen peripheral resistance; accumulation of uremic toxins | ↑ Muscle atrophy; stimulates hepatic stellate cells (fibrosis) | [54,71] |

| Natriuretic peptides | Cardiac stretch and heart failure | Improve lipid metabolism; may protect against NAFLD progression | [72,73] |

| Renokines | |||

| Erythropoietin | Hypoxia and anemia | Modulates insulin sensitivity; may reduce liver steatosis | [74,75] |

| Klotho | Kidney function regulation | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant; protective effect in MAFLD | [76,77] |

| NGAL | Renal tubular stress | A marker of kidney stress, correlated with the severity of liver injury | [78,79] |

| Renin | ↓ Renal perfusion; ↓ [Na+] in the distal tubule | Activation of the RAAS; worsening steatohepatitis | [73] |

| Adipokines | |||

| Adiponectin | Caloric restriction and healthy adipose tissue | Anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing; protective against liver steatosis and fibrosis | [80,81] |

| Leptin | Increased fat mass | Hyperleptinemia promotes hepatic inflammation and fibrosis; it is elevated in MAFLD | [82] |

| Resistin | Inflammation and obesity | ↑ Insulin resistance is associated with hepatic lipid accumulation | [83,84] |

| Visfatin | Visceral obesity and inflammation | Activates pro-inflammatory pathways; ↑ production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β; worsens steatohepatitis (NASH); ↑ liver fibrosis; ↑ oxidative stress | [85,86] |

| Osteokines | |||

| FGF-23 | Elevated levels in NAFLD | ↑ Insulin resistance | [87,88,89] |

| NGAL | Known as a biomarker for acute kidney injury | Organogenesis and modulation of inflammation; elevated in metabolic diseases, including liver diseases | [90] |

| Osteocalcin | Bone remodeling, mechanical loading | ↓ accumulation of lipids in the liver | [43,91] |

| Osteopontin | Inflammation and tissue injury | Promotes hepatic inflammation and fibrosis; elevated in MASLD and NASH | [92] |

| Sclerostin | Mechanical unloading of bone | Impairs insulin sensitivity; may contribute to metabolic dysfunction in liver disease | [93,94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maria Barbalho, S.; Laurindo, L.F.; Valenti, V.E.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Goulart, R.d.A. Organokine-Mediated Crosstalk: A Systems Biology Perspective on the Pathogenesis of MASLD—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311547

Maria Barbalho S, Laurindo LF, Valenti VE, Méndez-Sánchez N, Ramírez-Mejía MM, Goulart RdA. Organokine-Mediated Crosstalk: A Systems Biology Perspective on the Pathogenesis of MASLD—A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311547

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaria Barbalho, Sandra, Lucas Fornari Laurindo, Vitor Engracia Valenti, Nahum Méndez-Sánchez, Mariana M. Ramírez-Mejía, and Ricardo de Alvares Goulart. 2025. "Organokine-Mediated Crosstalk: A Systems Biology Perspective on the Pathogenesis of MASLD—A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311547

APA StyleMaria Barbalho, S., Laurindo, L. F., Valenti, V. E., Méndez-Sánchez, N., Ramírez-Mejía, M. M., & Goulart, R. d. A. (2025). Organokine-Mediated Crosstalk: A Systems Biology Perspective on the Pathogenesis of MASLD—A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311547