From Phytochemistry to Metabolic Regulation: The Insulin-Promoting Effects of Loureirin B Analogous to an Agonist of GLP-1 Receptor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

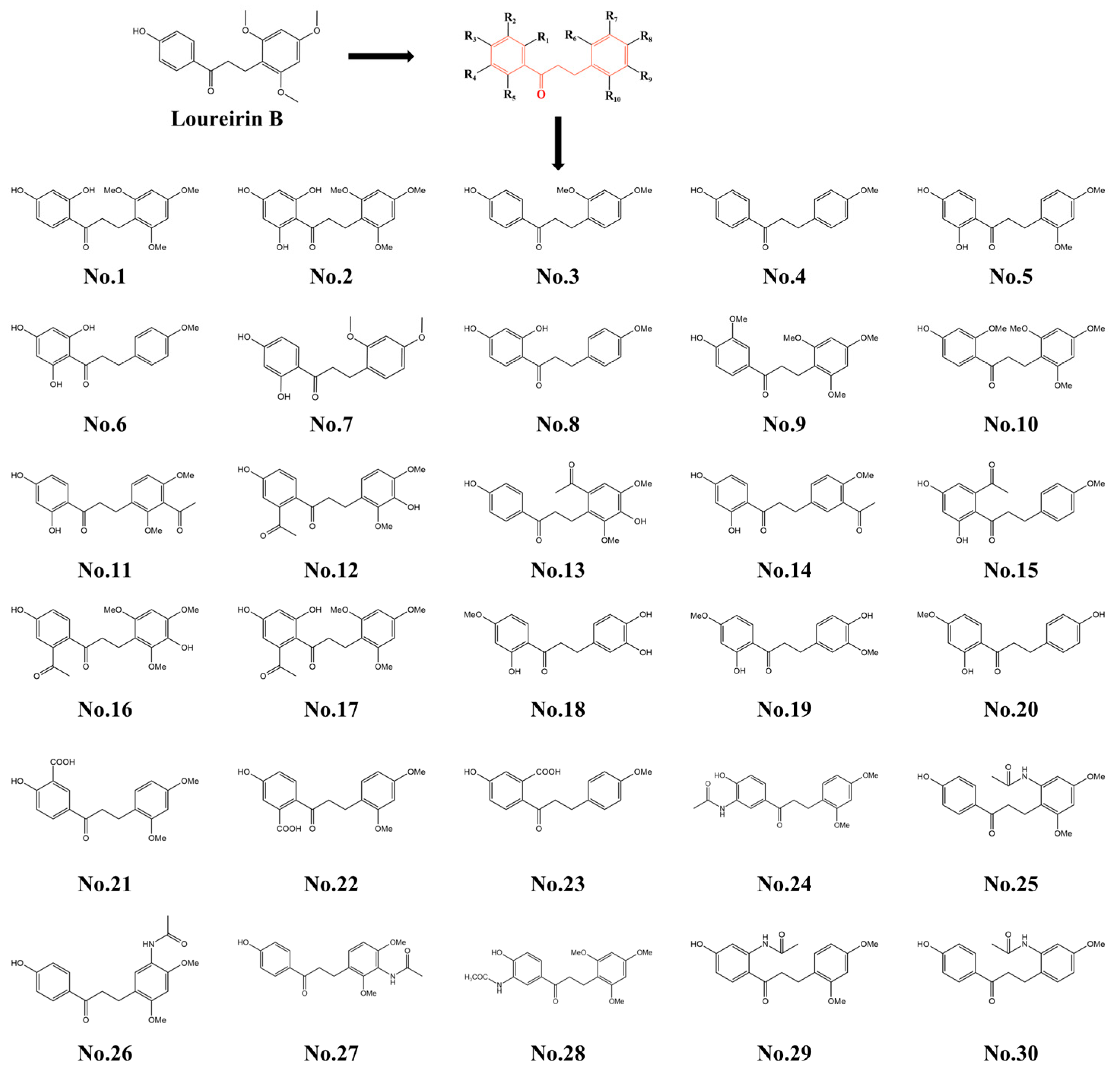

2.1. Screening and Synthesis of the Molecular Structures of Loureirin B Analogs

2.1.1. Screening of the Optimal Molecular Structure

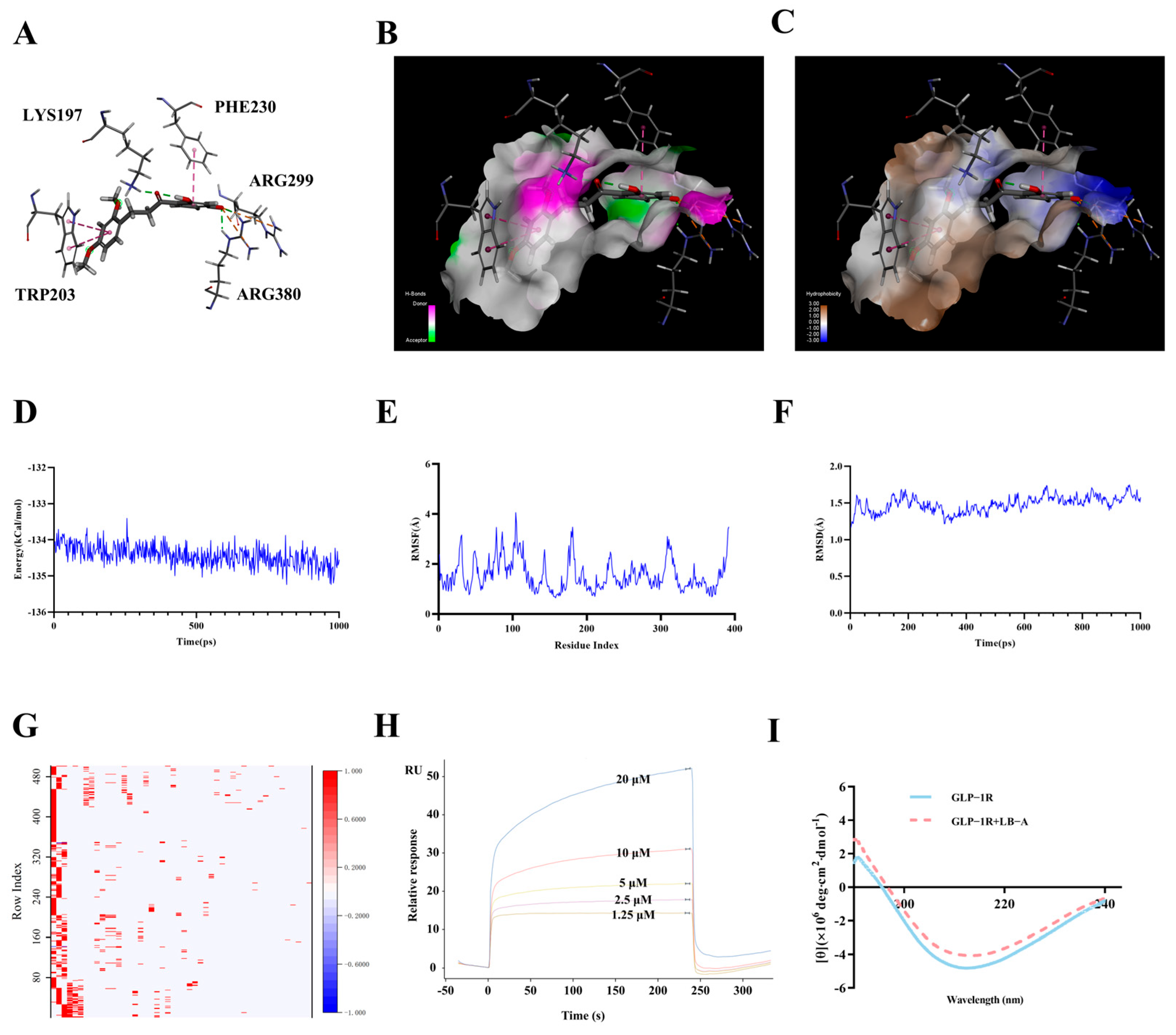

2.1.2. The Interaction Between LB-A and GLP-1R

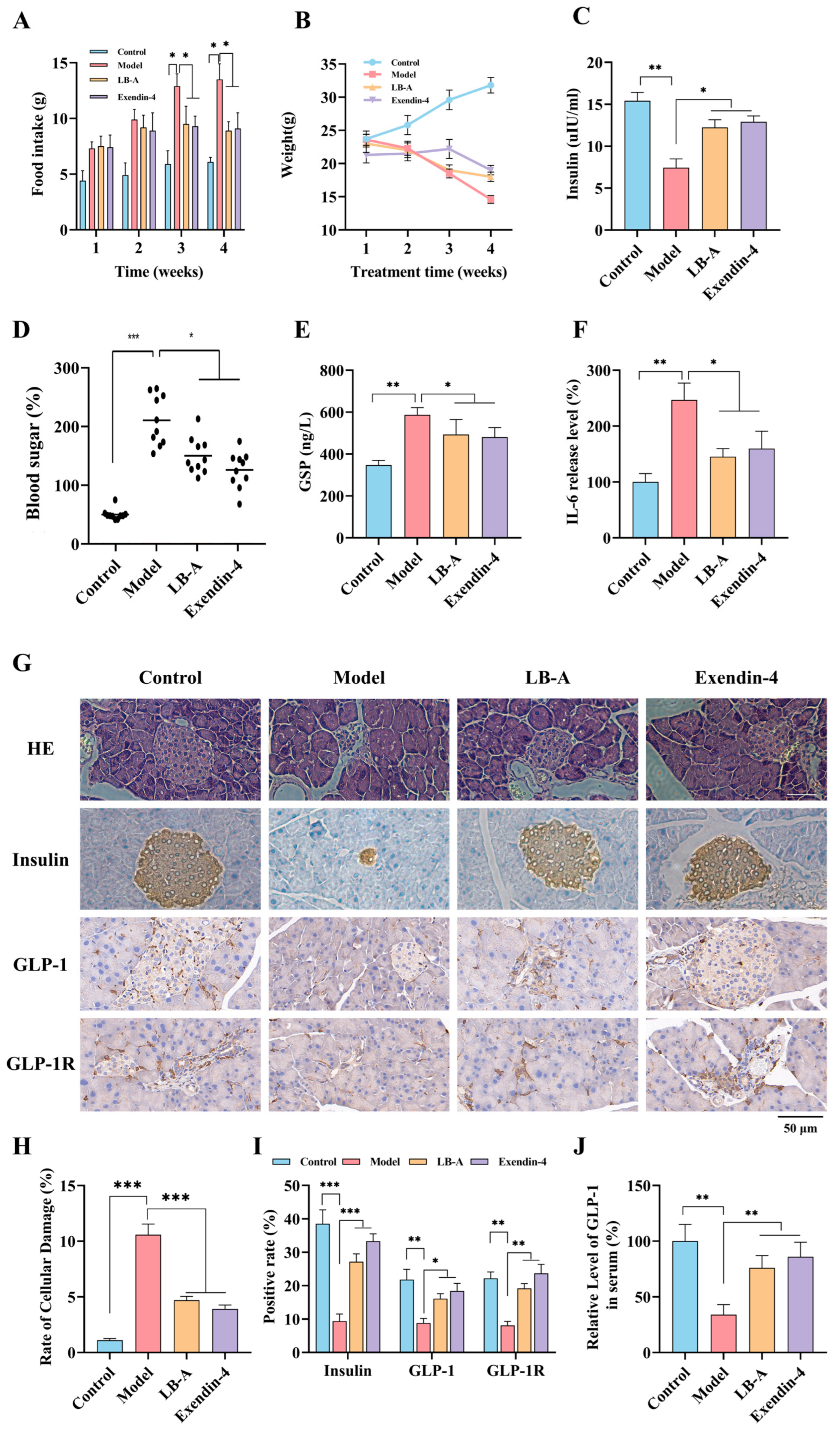

2.2. The Impact of LB-A on Diabetic Mice

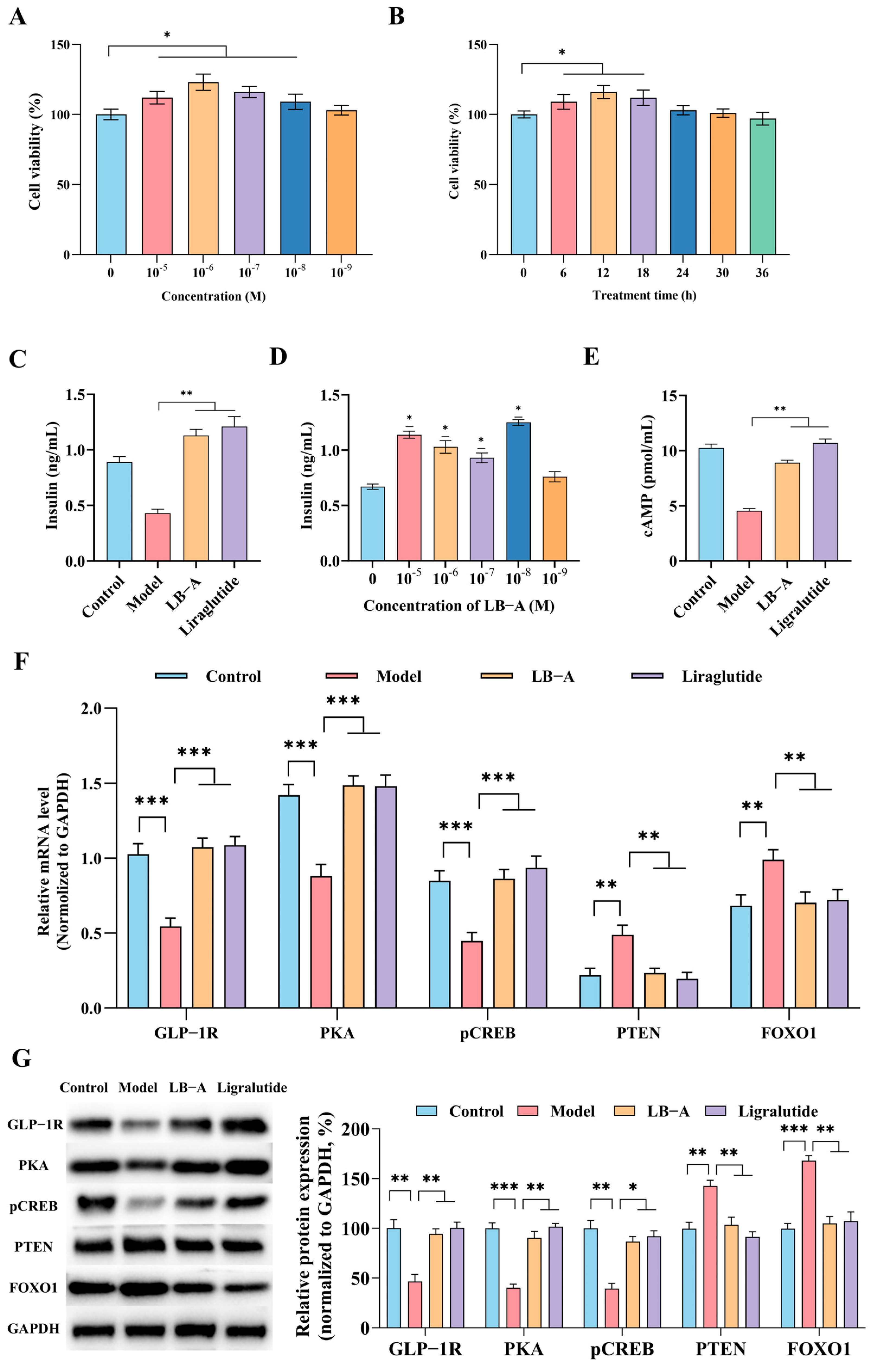

2.3. The Impact of LB-A on Ins-1 Cells

2.4. LB-A Enhances Insulin Secretion Through the Activation of GLP-1 Receptor

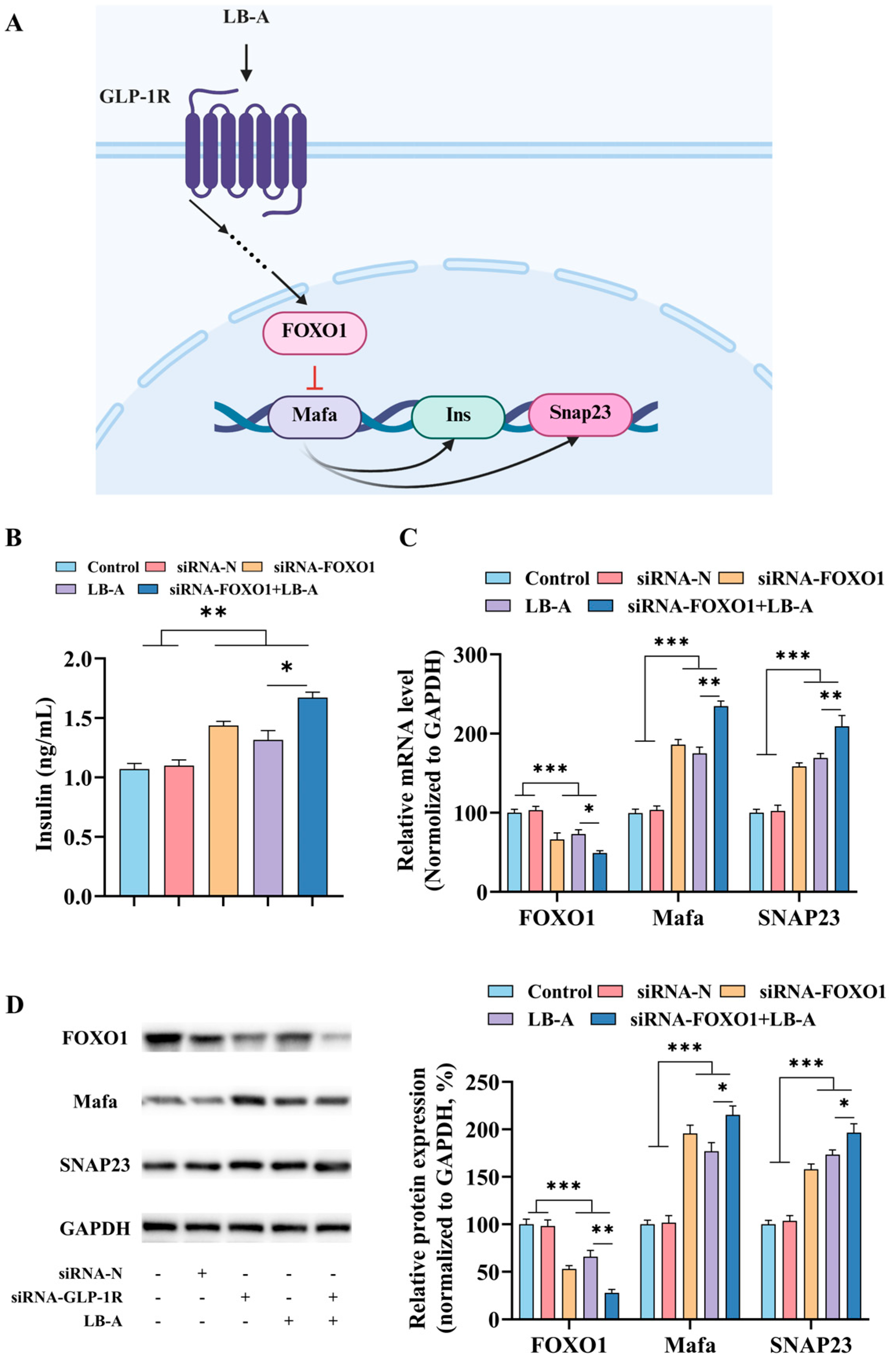

2.5. The Role of FOXO1 in the Promotion of Insulin Secretion by LB-A

3. Discussion

3.1. The Molecular Mechanism Underlying the Interaction Between the Structural Optimization of LB-A and GLP-1R

3.2. Pharmacodynamic Assessment of LB-A

3.3. The Regulatory Mechanism of LB-A

3.4. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Construction and Screening of Loureirin B Derivatives

4.2.2. Synthesis of Loureirin B Analog (LB-A)

4.2.3. Construction of Diabetic Model Mice

4.2.4. Detection of Physiological Indicators in Mice

4.2.5. Tissue Staining in Mice

4.2.6. Pharmacokinetics

4.2.7. SPR and CD

4.2.8. Ins-1 Cell Viability Assay

4.2.9. Detection of cAMP Level in Ins-1 Cells

4.2.10. Ins-1 Cell Proliferation Assay

4.2.11. Ins-1 Cell Apoptosis Detection

4.2.12. Ins-1 Cell ROS Assay

4.2.13. qPCR and WB

4.2.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogle, G.D.; Wang, F.; Haynes, A.; Gregory, G.A.; King, T.W.; Deng, K.; Dabelea, D.; James, S.; Jenkins, A.J.; Li, X.; et al. Global type 1 diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality estimates 2025: Results from the International diabetes Federation Atlas, 11th Edition, and the T1D Index Version 3.0. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 225, 112277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Nagendra, L.; Anne, B.; Kumar, M.; Sharma, M.; Kamrul-Hasan, A.B.M. Orforglipron, a novel non-peptide oral daily glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist as an anti-obesity medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.R.; Frias, J.P.; Brown, L.S.; Gorman, D.N.; Vasas, S.; Tsamandouras, N.; Birnbaum, M.J. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Small Molecule Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Danuglipron for Glycemic Control Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Zhou, R.P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, H.L.; Ye, Z.; Xu, Y.M.; Feng, S.; Shu, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of HRS-7535, a novel oral small molecule glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, in healthy participants: A phase 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single- and multiple-ascending dose, and food effect trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.K.; Anwar, S.; Hasan, G.M.; Shamsi, A.; Islam, A.; Parvez, S.; Hassan, M.I. Comprehensive Insights into Biological Roles of Rosmarinic Acid: Implications in Diabetes, Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadzadeh, A.M.; Aliabadi, M.M.; Mirheidari, S.B.; Hamedi-Asil, M.; Garousi, S.; Mottahedi, M.; Sahebkar, A. Beneficial effects of resveratrol on diabetes mellitus and its complications: Focus on mechanisms of action. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 2407–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Xia, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Niu, B. Loureirin B activates GLP-1R and promotes insulin secretion in Ins-1 cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyandwi, J.B.; Ko, Y.S.; Jin, H.; Yun, S.P.; Park, S.W.; Kim, H.J. Rosmarinic Acid Exhibits a Lipid-Lowering Effect by Modulating the Expression of Reverse Cholesterol Transporters and Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Hartogh, D.J.; Vlavcheski, F.; Giacca, A.; Tsiani, E. Attenuation of Free Fatty Acid (FFA)-Induced Skeletal Muscle Cell Insulin Resistance by Resveratrol is Linked to Activation of AMPK and Inhibition of mTOR and p70 S6K. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hou, P.; Yao, Y.; Yue, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, L.; Mi, M. Dihydromyricetin Improves High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperglycemia through ILC3 Activation via a SIRT3-Dependent Mechanism. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Gao, L.; Yao, R.; Zhang, Y. Baicalin promotes the activation of brown and white adipose tissue through AMPK/PGC1a pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 922, 174913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Cao, W.; Zhao, L.; Han, Q.; Yang, S.; Yang, K.; Pan, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. Design, Synthesis, and Antitumor Evaluation of Novel Mono-Carbonyl Curcumin Analogs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Lian, B.-P.; Xia, Y.-Z.; Shao, Y.-Y.; Kong, L.-Y. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of resveratrol-cinnamoyl derivates as tubulin polymerization inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 93, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbalaei, S.; Chang, R.-L.; Zhou, Q.-T.; Chen, Y.; Dai, A.-T.; Wang, M.-W.; Yang, D.-H. Effects of site-directed mutagenesis of GLP-1 and glucagon receptors on signal transduction activated by dual and triple agonists. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, M.-W. Structural pharmacology and mechanisms of GLP-1R signaling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.-N.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Liang, A.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Dai, A.; Xia, T.; et al. Structural basis of peptidomimetic agonism revealed by small-molecule GLP-1R agonists Boc5 and WB4-24. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200155119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Belousoff, M.J.; Zhao, P.; Kooistra, A.J.; Truong, T.T.; Ang, S.Y.; Underwood, C.R.; Egebjerg, T.; Senel, P.; Stewart, G.D.; et al. Differential GLP-1R Binding and Activation by Peptide and Non-peptide Agonists. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard, F.S.; Ho, J.D.; Sloop, K.W. Discovery and pharmacology of the covalent GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) allosteric modulator BETP: A novel tool to probe GLP-1R pharmacology. Adv. Pharmacol. 2020, 88, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Sun, B.; Yoshino, H.; Feng, D.; Suzuki, Y.; Fukazawa, M.; Nagao, S.; Wainscott, D.B.; Showalter, A.D.; Droz, B.A.; et al. Structural basis for GLP-1 receptor activation by LY3502970, an orally active nonpeptide agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 29959–29967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Hamamoto, Y.; Deenadayalan, S.; Navarria, A.; Nishijima, K.; Seino, Y.; Investigators, P. Dose-response, efficacy, and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 9): A 52-week, phase 2/3a, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liao, J.; Li, N.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, L.; Chen, K.; et al. A nonpeptidic agonist of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors with efficacy in diabetic db/db mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Guan, N.; Gao, W.-w.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.-Y.; Ma, D.-W.; Zhong, D.-F.; Ge, G.-B.; Li, C.; Chen, X.-Y.; et al. A continued saga of Boc5, the first non-peptidic glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist with in vivo activities. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, L.L.; Drucker, D.J. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2131–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, T.V.; Kabakchieva, P.P.; Assyov, Y.S.; Georgiev, T.A. Targeting Inflammatory Cytokines to Improve Type 2 Diabetes Control. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Cui, X.; Guo, T.; Wei, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.; Yan, W.; Chen, L. Baicalein Ameliorates Insulin Resistance of HFD/STZ Mice Through Activating PI3K/AKT Signal Pathway of Liver and Skeletal Muscle in a GLP-1R-Dependent Manner. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Q.; Guo, X.; Zhan, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, X.; Ye, B.; Wan, S. The GLP-1 agonist, liraglutide, ameliorates inflammation through the activation of the PKA/CREB pathway in a rat model of knee osteoarthritis. J. Inflamm. 2019, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.; Dinda, M.; Kulsi, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Dinda, S. Therapeutic potentials of plant iridoids in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 169, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafirovska, M.; Zafirovski, A.; Rezen, T.; Pintar, T. The Outcome of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery in Morbidly Obese Patients with Different Genetic Variants Associated with Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeta, T.; Aoyama, M.; Bando, Y.K.; Monji, A.; Mitsui, T.; Takatsu, M.; Cheng, X.-W.; Okumura, T.; Hirashiki, A.; Nagata, K.; et al. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Modulates Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Chronic Heart Failure via Angiogenesis-Dependent and -Independent Actions. Circulation 2012, 126, 1838–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.; McGlone, E.R.; Fang, Z.; Pickford, P.; Correa, I.R., Jr.; Oishi, A.; Jockers, R.; Inoue, A.; Kumar, S.; Gorlitz, F.; et al. Genetic and biased agonist-mediated reductions in β-arrestin recruitment prolong cAMP signaling at glucagon family receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.W.; Sun, X.D.; Ding, Y.T.; Niu, B.; Chen, Q. Loureirin B analogs mitigate oxidative stress and confer renal protection. Cell. Signal. 2025, 132, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, R.; Hergarden, A.; Krishnan, S.; Morales, M.; Lam, D.; Tracy, T.; Tang, T.; Patton, A.; Lee, C.; Pant, A.; et al. Biased agonism of GLP-1R and GIPR enhances glucose lowering and weight loss, with dual GLP-1R/GIPR biased agonism yielding greater efficacy. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.J.; Xu, Z.; Zou, H.X.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zhu, R.; Wang, B.; et al. Discovery of ecnoglutide-A novel, long-acting, cAMP-biased glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog. Mol. Metab. 2023, 75, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, C.E.; Peace, E.; Chen, S.Q.; Davies, I.; El Eid, L.; Tomas, A.; Tan, T.C.; Minnion, J.; Jones, B.; Bloom, S.R. Abolishing β-arrestin recruitment is necessary for the full metabolic benefits of G protein-biased glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Shao, S. Exenatide regulates Th17/Treg balance via PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 pathway in db/db mice. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Dai, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. Liraglutide combined with HIIT preserves contractile apparatus and blunts the progression of heart failure in diabetic cardiomyopathy rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.S.; de Paiva, I.H.R.; Mendonca, I.P.; de Souza, J.R.B.; Lucena-Silva, N.; Peixoto, C.A. Anorexigenic and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways of semaglutide via the microbiota-gut–brain axis in obese mice. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 33, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, A.J.; Ramalli, S.G.; Wallace, B.A. DichroWeb, a website for calculating protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | -cDocker Energy | Bone Length | Acting Force |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56.54 | 2.06 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Donor Hydrogen Bond |

| 2 | 44.49 | 2.42 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation |

| 3 | 56.98 | 2.88 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi T-shaped, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 4 | 58.22 | 2.06 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Pi Stacked |

| 5 | 56.37 | 2.09 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation, Salt Bridge |

| 6 | 55.69 | 2.20 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, |

| 7 | 59.87 | 2.04 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked, Pi-Cation |

| 8 | 56.35 | 2.15 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 9 | 51.72 | 2.74 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked, Pi-Alkyl |

| 10 | 54.00 | 2.08 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation |

| 11 | 56.26 | 2.58 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl |

| 12 | 56.10 | 2.38 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked |

| 13 | 55.75 | 2.34 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

| 14 | 53.66 | 1.93 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked, |

| 15 | 52.10 | 1.82 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl |

| 16 | 52.30 | 2.18 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 17 | 55.54 | 2.25 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 18 | 30.97 | 2.42 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked, Pi-Cation |

| 19 | 20.91 | 2.2 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Cation |

| 20 | 28.19 | 1.94 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 21 | 51.67 | 1.71 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation |

| 22 | 53.05 | 1.95 | Salt Bridge, Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

| 23 | 54.49 | 1.89 | Salt Bridge, Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl |

| 24 | 55.64 | 2.09 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation |

| 25 | 49.13 | 1.86 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked, Pi-Alkyl |

| 26 | 52.25 | 2.06 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Cation |

| 27 | 53.98 | 2.07 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| 28 | 52.51 | 2.19 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked |

| 29 | 33.78 | 2.14 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Cation |

| 30 | 48.92 | 2.28 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Pi-Pi Stacked |

| LB [7] | 40.42 | 2.33 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| Structure | Regular α-Helix a | Irregular α-Helix a | Regular β-Folding a | Irregular β-Folding a | β-Turn a | Random Coil a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1R | 12.2 | 10.8 | 24.2 | 10.5 | 16.6 | 25.7 |

| GLP-1R + LB-A | 11.4 | 10.6 | 25.6 | 9.9 | 17.1 | 26.3 |

| Genes | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GPL-1R | GGGCCAGTAGTGTGCTACAA | CTTCACACTCCGACAGGTCC |

| PKA | TACTTGGCCCCCGAGATTATC | GCGAAGAAGGGTGGGTAACC |

| pCREB | TGCCCCTGGAGTTGTTATGG | CTCTTGCTGCCTCCCTGTTC |

| PTEN | TGGATTCGACTTAGACTTGACCT | GGTGGGTTATGGTCTTCAAAAGG |

| FOXO1 | CACCATGATGCAGCAGACGC | CAACTCCTTCAAGCCTCCAG |

| Mafa | CTTCAGCAAGGAGGAGGGTCATC | GCGTAGCCGCGGTTCTT |

| SNAP23 | GCCACAGCATTTGTTGAGTTC | GCAGGAATCAAGACCATCACT |

| GAPDH | GGCAAGTTCAACGGCACAGT | TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTAGACTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, H.; Sun, X.; Ding, Y.; Gu, S.; Niu, B.; Chen, Q. From Phytochemistry to Metabolic Regulation: The Insulin-Promoting Effects of Loureirin B Analogous to an Agonist of GLP-1 Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311548

Fang H, Sun X, Ding Y, Gu S, Niu B, Chen Q. From Phytochemistry to Metabolic Regulation: The Insulin-Promoting Effects of Loureirin B Analogous to an Agonist of GLP-1 Receptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311548

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Haowen, Xiaodong Sun, Yanting Ding, Siyuan Gu, Bing Niu, and Qin Chen. 2025. "From Phytochemistry to Metabolic Regulation: The Insulin-Promoting Effects of Loureirin B Analogous to an Agonist of GLP-1 Receptor" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311548

APA StyleFang, H., Sun, X., Ding, Y., Gu, S., Niu, B., & Chen, Q. (2025). From Phytochemistry to Metabolic Regulation: The Insulin-Promoting Effects of Loureirin B Analogous to an Agonist of GLP-1 Receptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311548