PolyQ Expansion Controls Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of the N-Terminal Fragments of Ataxin-2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

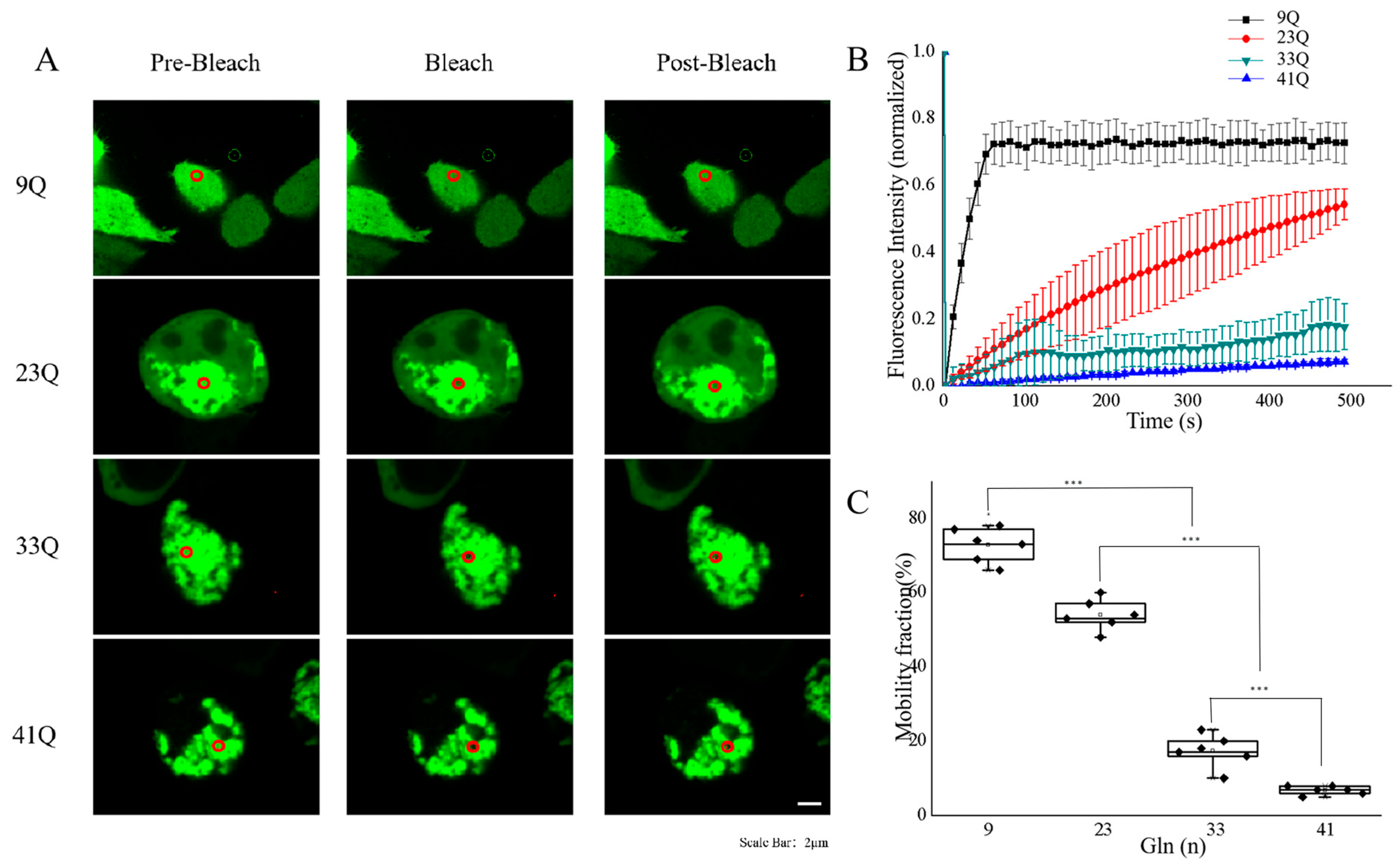

2.1. PolyQ Expansion Reduces the Molecular Mobility of Atx2-N317 in Cells

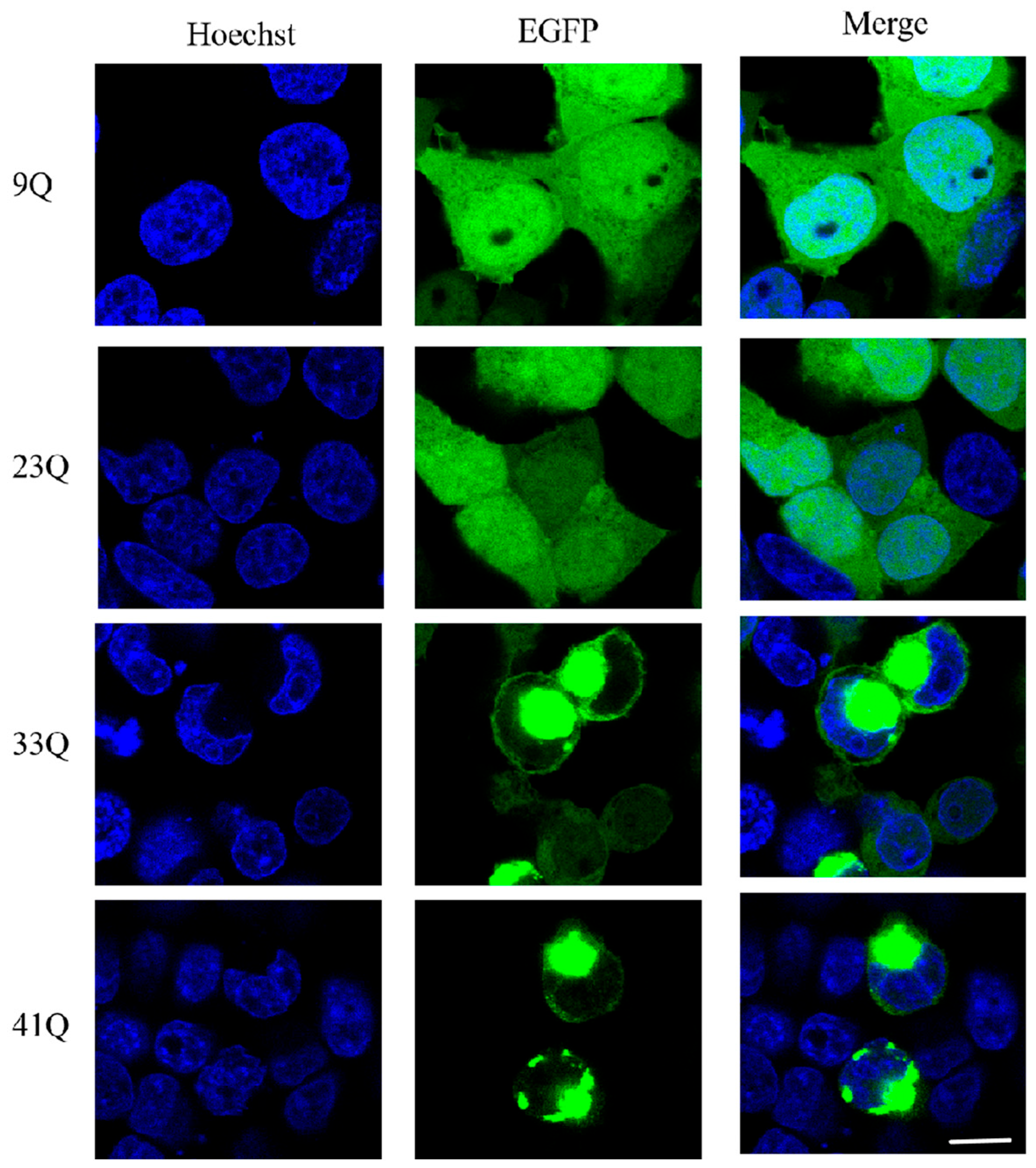

2.2. Status and Distribution of PolyQ-Expanded Atx2-N81 in Cells

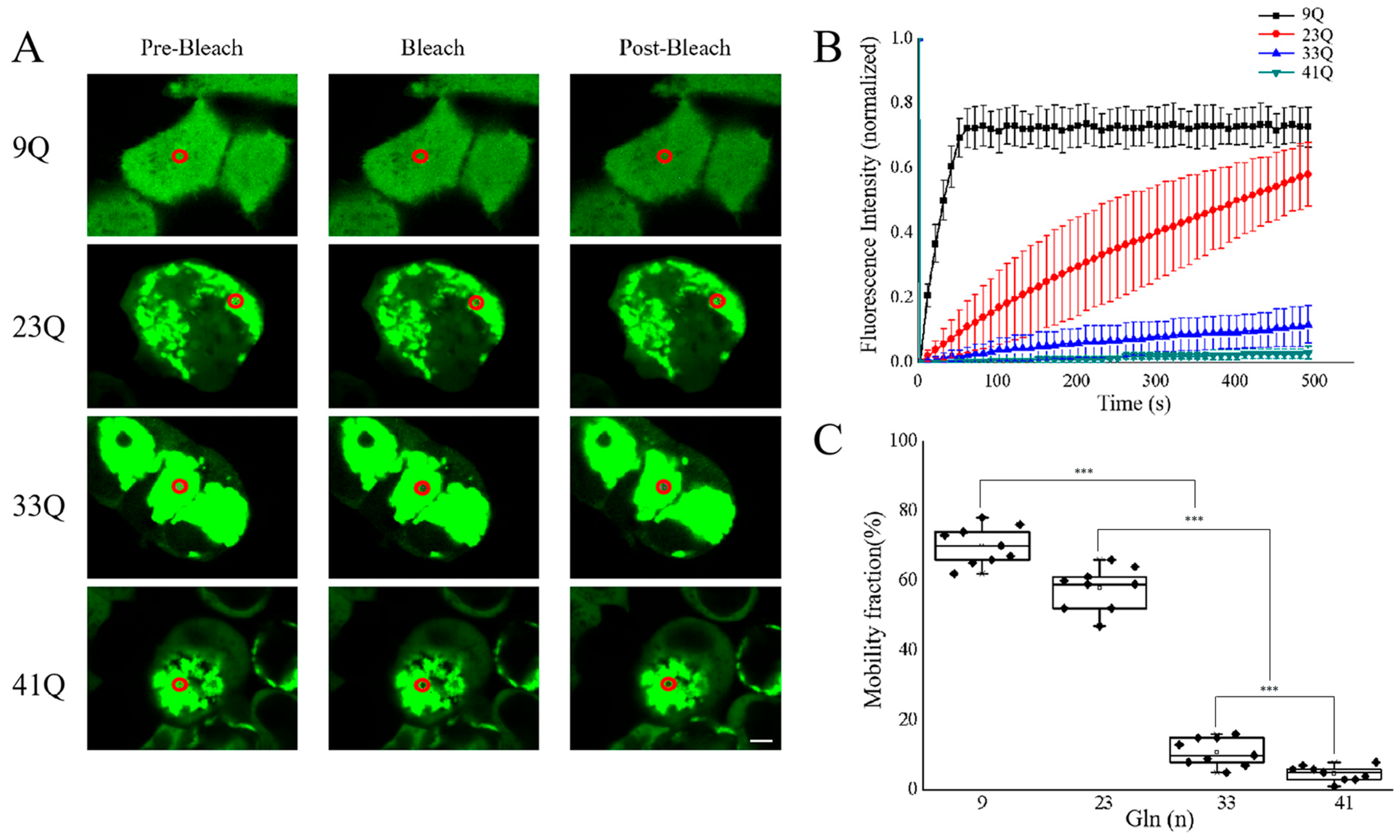

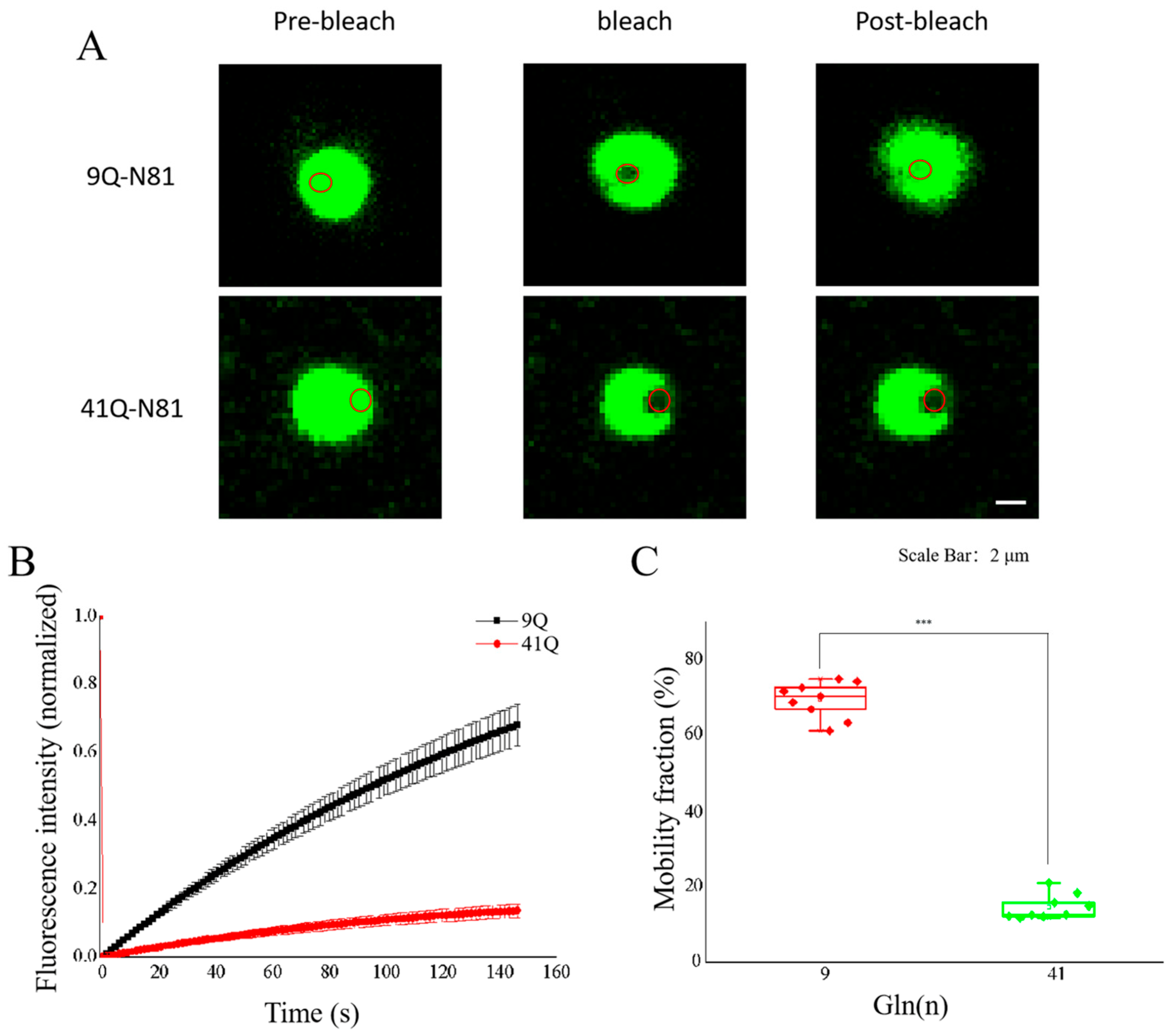

2.3. Molecular Mobility of Atx2-N81 with Different PolyQ Expansions

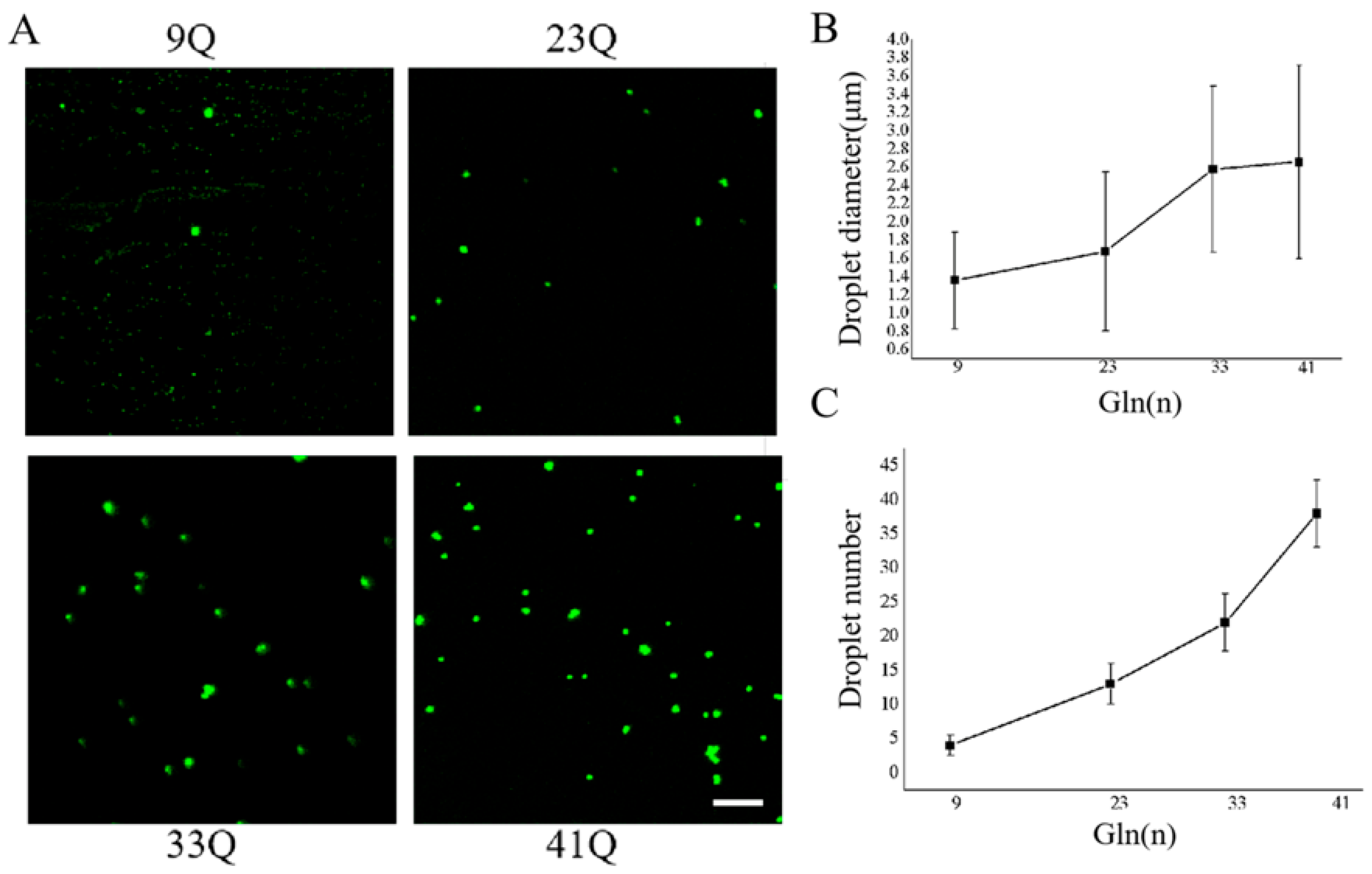

2.4. PolyQ Expansion Promotes Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of Atx2-N81 In Vitro

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmids and Reagents

4.2. Cell Culture and Plasmid Transfection

4.3. Immunofluorescence Imaging

4.4. Purification of EGFP-Atx2-N81 Proteins

4.5. Phase Separation Experiment In Vitro

4.6. Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Atx2 | Ataxin-2 |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| EGFP | Enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FPLC | Fast protein liquid chromatography |

| FRAP | Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching |

| LCD | Low-complexity domain |

| LSm | Like Sm |

| LSmAD | LSm-associated domain |

| PAM2 | PABP-binding motif 2 |

| P-body | Processing body |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| polyQ | polyglutamine; |

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| SCA2 | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| SG | Stress granule |

| TRITC | Tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate |

References

- Lieberman, A.P.; Shakkottai, V.G.; Albin, R.L. Polyglutamine Repeats in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Polyglutamine (PolyQ) Diseases: Navigating the Landscape of Neurodegeneration. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 2665–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J.; Han, M.H.; Bagley, J.A.; Hyeon, D.Y.; Ko, B.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Cha, I.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.M.; et al. Coiled-coil structure-dependent interactions between polyQ proteins and Foxo lead to dendrite pathology and behavioral defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10748–E10757, Correction in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, B.S.; Lipiński, W.P.; Spruijt, E. The role of biomolecular condensates in protein aggregation. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamazaki, T. A guide to membraneless organelles and their various roles in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio, G.L.; Thomas, M.G.; García, C.C. Membraneless Organelles and Condensates Orchestrate Innate Immunity Against Viruses. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxreiter, M.; Vendruscolo, M. Generic nature of the condensed states of proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, H. Sequestration of cellular interacting partners by protein aggregates: Implication in a loss-of-function pathology. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3705–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Y.; Liu, Y.J. Sequestration of cellular native factors by biomolecular assemblies: Physiological or pathological? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2022, 1869, 119360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Iso, N.; Norizoe, Y.; Sakaue, T.; Yoshimura, S.H. Charge block-driven liquid–liquid phase separation—Mechanism and biological roles. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs261394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, L.; Renard, D.; Solé-Jamault, V.; Giuliani, A.; Boire, A. Role of protein conformation and weak interactions on γ-gliadin liquid-liquid phase separation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lin, Y.-H.; Vernon, R.M.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Chan, H.S. Comparative roles of charge, π, and hydrophobic interactions in sequence-dependent phase separation of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28795–28805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struhl, K. Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs): A vague and confusing concept for protein function. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 1186–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, J.; Ryan, V.H.; Fawzi, N.L. The SH3 domain of Fyn kinase interacts with and induces liquid–liquid phase separation of the low-complexity domain of hnRNPA2. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 19522–19531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fefilova, A.S.; Fonin, A.V.; Vishnyakov, I.E.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K. Stress-Induced Membraneless Organelles in Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes: Bird’s-Eye View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaips, C.L.; Jayaraj, G.G.; Hartl, F.U. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziortzouda, P.; Bosch, L.V.D.; Hirth, F. Triad of TDP43 control in neurodegeneration: Autoregulation, localization and aggregation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Lee, H.O.; Jawerth, L.; Maharana, S.; Jahnel, M.; Hein, M.Y.; Stoynov, S.; Mahamid, J.; Saha, S.; Franzmann, T.M.; et al. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 2015, 162, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Itoh, T.Q.; Lim, C. Ataxin-2: A versatile posttranscriptional regulator and its implication in neural function. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2018, 9, e1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S.; Dorone, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Shabardina, V.; Huang, G.; Marian, A.; Kim, G.; Sanyal, A.; Şen, N.-E.; Griffith, D.; et al. Poly(A)-binding protein is an ataxin-2 chaperone that regulates biomolecular condensates. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2020-2034.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.G.; Conceição, A.; Matos, C.A.; Nóbrega, C. The polyglutamine protein ATXN2: From its molecular functions to its involvement in disease. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, R.; Inagaki, H.; Suzuki, J.; Hosoda, N.; Sugiyama, H.; Tomita, K.; Hotta, T.; Hoshino, S.-I. Concerted action of ataxin-2 and PABPC1-bound mRNA poly(A) tail in the formation of stress granules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 9193–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaehler, C.; Isensee, J.; Nonhoff, U.; Terrey, M.; Hucho, T.; Lehrach, H.; Krobitsch, S. Ataxin-2-Like Is a Regulator of Stress Granules and Processing Bodies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonhoff, U.; Ralser, M.; Welzel, F.; Piccini, I.; Balzereit, D.; Yaspo, M.-L.; Lehrach, H.; Krobitsch, S. Ataxin-2 Interacts with the DEAD/H-Box RNA Helicase DDX6 and Interferes with P-Bodies and Stress Granules. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; Zhang, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-H.; Jiang, L.-L.; Hu, H.-Y. PolyQ-expanded ataxin-2 aggregation impairs cellular processing-body homeostasis via sequestering the RNA helicase DDX6. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Golatta, M.; Wüllner, U.; Lengauer, T. Structural and functional analysis of ataxin-2 and ataxin-3. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 3155–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Hu, H.-Y.; Lu, C. The LSmAD Domain of Ataxin-2 Modulates the Structure and RNA Binding of Its Preceding LSm Domain. Cells 2025, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, N.; Mangus, D.A.; Chang, T.-C.; Palermino, J.-M.; Shyu, A.-B.; Gehring, K. Poly(A) Nuclease Interacts with the C-terminal Domain of Polyadenylate-binding Protein Domain from Poly(A)-binding Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25067–25075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrauskas, A.; Fortunati, D.L.; Kandi, A.R.; Pothapragada, S.S.; Agrawal, K.; Singh, A.; Huelsmeier, J.; Hillebrand, J.; Brown, G.; Chaturvedi, D.; et al. Structured and disordered regions of Ataxin-2 contribute differently to the specificity and efficiency of mRNP granule formation. PLOS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavachalu, B.; Huelsmeier, J.; Sudhakaran, I.P.; Hillebrand, J.; Singh, A.; Petrauskas, A.; Thiagarajan, D.; Sankaranarayanan, M.; Mizoue, L.; Anderson, E.N.; et al. RNP-Granule Assembly via Ataxin-2 Disordered Domains Is Required for Long-Term Memory and Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2018, 98, 754–766.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elden, A.C.; Kim, H.-J.; Hart, M.P.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Johnson, B.S.; Fang, X.; Armakola, M.; Geser, F.; Greene, R.; Lu, M.M.; et al. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature 2010, 466, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Li, Y.R.; Ingre, C.; Weber, M.; Grehl, T.; Gredal, O.; de Carvalho, M.; Meyer, T.; Tysnes, O.-B.; Auburger, G.; et al. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions in European ALS patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira de Sá, R.; Sudria-Lopez, E.; Cañizares Luna, M.; Harschnitz, O.; van den Heuvel, D.M.; Kling, S.; Vonk, D.; Westeneng, H.J.; Karst, H.; Bloemenkamp, L.; et al. ATAXIN-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions elicit ALS-associated metabolic and immune phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffita-Mesa, J.M.; Paucar, M.; Svenningsson, P. Ataxin-2 gene: A powerful modulator of neurological disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2021, 34, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulst, S.-M.; Nechiporuk, A.; Nechiporuk, T.; Gispert, S.; Chen, X.-N.; Lopes-Cendes, I.; Pearlman, S.; Starkman, S.; Orozco-Diaz, G.; Lunkes, A.; et al. Moderate expansion of a normally biallelic trinucleotide repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nat. Genet. 1996, 14, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoles, D.R.; Pulst, S.M. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1049, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Egorova, P.A.; Bezprozvanny, I.B. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutics for Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 1050–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, H.G.; Franklin, J.P.; Alix, J.J.P.; Moll, T.; Pattrick, M.; Cooper-Knock, J.; Shanmugarajah, P.; Beauchamp, N.J.; Hadjivissiliou, M.; Paling, D.; et al. Simultaneous ALS and SCA2 associated with an intermediate-length ATXN2 CAG-repeat expansion. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatos, A.; E Tosatto, S.C.; Vendruscolo, M.; Fuxreiter, M. FuzDrop on AlphaFold: Visualizing the sequence-dependent propensity of liquid–liquid phase separation and aggregation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W337–W344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molliex, A.; Temirov, J.; Lee, J.; Coughlin, M.; Kanagaraj, A.P.; Kim, H.J.; Mittag, T.; Taylor, J.P. Phase Separation by Low Complexity Domains Promotes Stress Granule Assembly and Drives Pathological Fibrillization. Cell 2015, 163, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satterfield, T.F.; Pallanck, L.J. Ataxin-2 and its Drosophila homolog, ATX2, physically assemble with polyribosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2523–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Hu, H. Ataxin-2 sequesters Raptor into aggregates and impairs cellular mTORC1 signaling. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 1795–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Saha, S.; Woodruff, J.B.; Franzmann, T.M.; Wang, J.; Hyman, A.A. A User’s Guide for Phase Separation Assays with Purified Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 4806–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.-H.; Duan, H.-T.; Jiang, L.-L.; Hu, H.-Y. PolyQ Expansion Controls Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of the N-Terminal Fragments of Ataxin-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311538

Liu Y-H, Duan H-T, Jiang L-L, Hu H-Y. PolyQ Expansion Controls Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of the N-Terminal Fragments of Ataxin-2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311538

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yin-Hu, Heng-Tong Duan, Lei-Lei Jiang, and Hong-Yu Hu. 2025. "PolyQ Expansion Controls Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of the N-Terminal Fragments of Ataxin-2" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311538

APA StyleLiu, Y.-H., Duan, H.-T., Jiang, L.-L., & Hu, H.-Y. (2025). PolyQ Expansion Controls Biomolecular Condensation and Aggregation of the N-Terminal Fragments of Ataxin-2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311538