The Fluidic Connectome in Brain Disease: Integrating Aquaporin-4 Polarity with Multisystem Pathways in Neurodegeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction: From Peripheral Symptom to Central Driver

2. Molecular Blueprint of AQP4 Polarization: Anchoring, Regulation, and Dynamics

2.1. Anchoring Architecture: The Dystrophin–Syntrophin Scaffold and Perivascular Niche

2.2. Isoform Diversity and Orthogonal Arrays: Structural Determinants of Polarized Function

2.3. Vesicular Trafficking and Membrane Domain Segregation

2.4. Multilayered Regulation: Transcriptional, Post-Translational, and Cytoskeletal Control

2.5. Dynamic Remodeling: Spatial and Temporal Adaptation of AQP4 Microdomains

2.6. Systems Integration: A Fragile Equilibrium of Interdependent Modules

2.7. Conclusions of Section 2

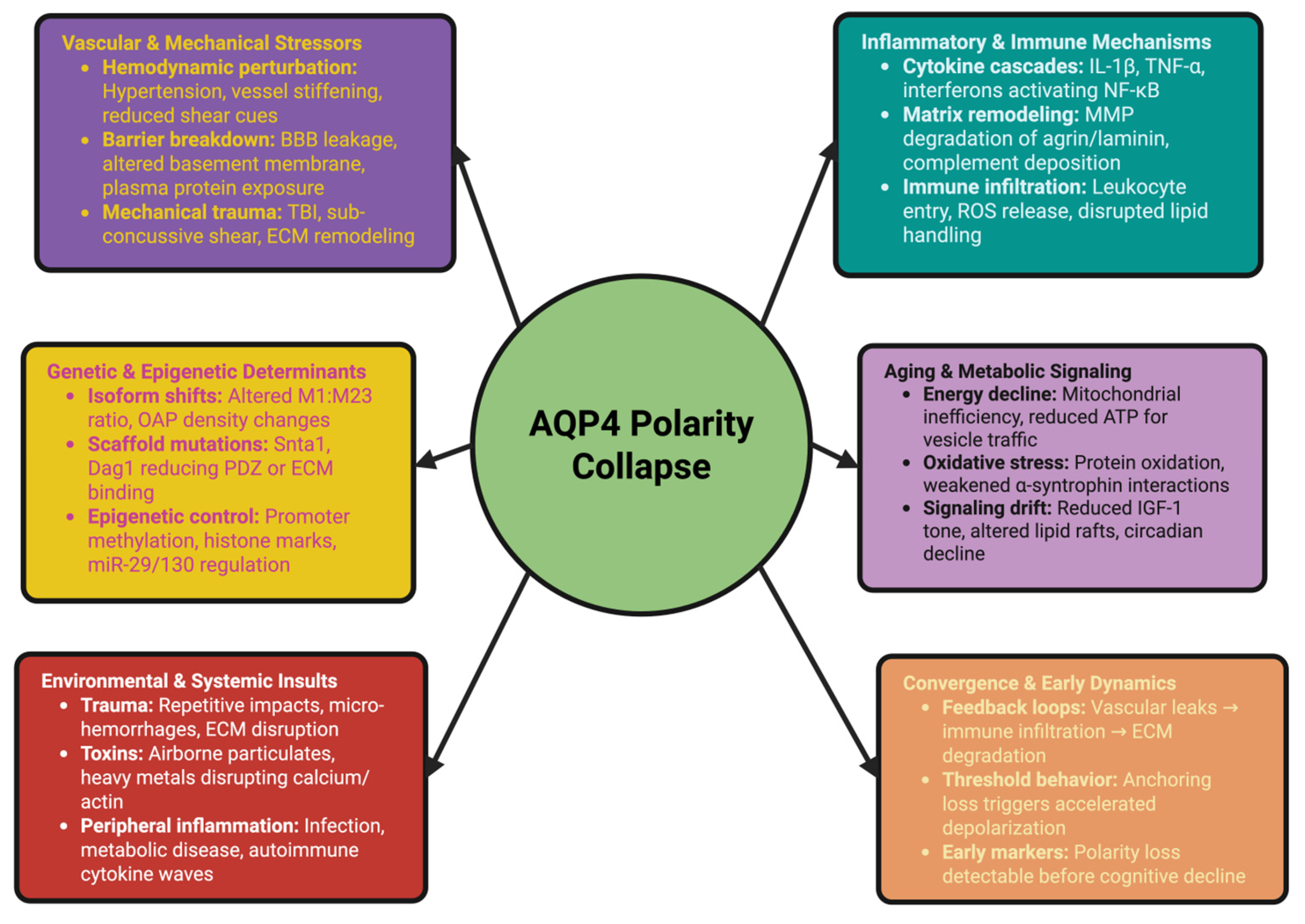

3. Collapse Unleashed: Triggers and Early Events in AQP4 Depolarization

3.1. Vascular and Mechanical Stressors: Hemodynamic Perturbation and Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown

3.2. Inflammatory and Immune Mechanisms: Cytokine Cascades and Glial Signaling

3.3. Genetic and Epigenetic Determinants: Predisposition and Molecular Vulnerability

3.4. Aging and Metabolic Signaling: Gradual Erosion of the Polarity Network

3.5. Environmental and Systemic Insults: Trauma, Toxins, and Peripheral Inflammation

3.6. Convergence and Early Dynamics: Synergy Among Triggers

3.7. Conclusions of Section 3

4. Glymphatic System Disintegration: The Hydraulic Consequences of AQP4 Failure

4.1. Disruption of Perivascular Fluid Architecture and Pressure Dynamics

4.2. Failure of Convective Solute Transport and Self-Propagating Accumulation

4.3. Temporal Collapse: Disintegration of Circadian Clearance Rhythms

4.4. Structural Remodeling of Perivascular Spaces: From Fluid Stasis to Architectural Failure

4.5. Translational Implications: Biomarkers, Therapeutics, and Diagnostic Frontiers

4.6. Conclusions of Section 4

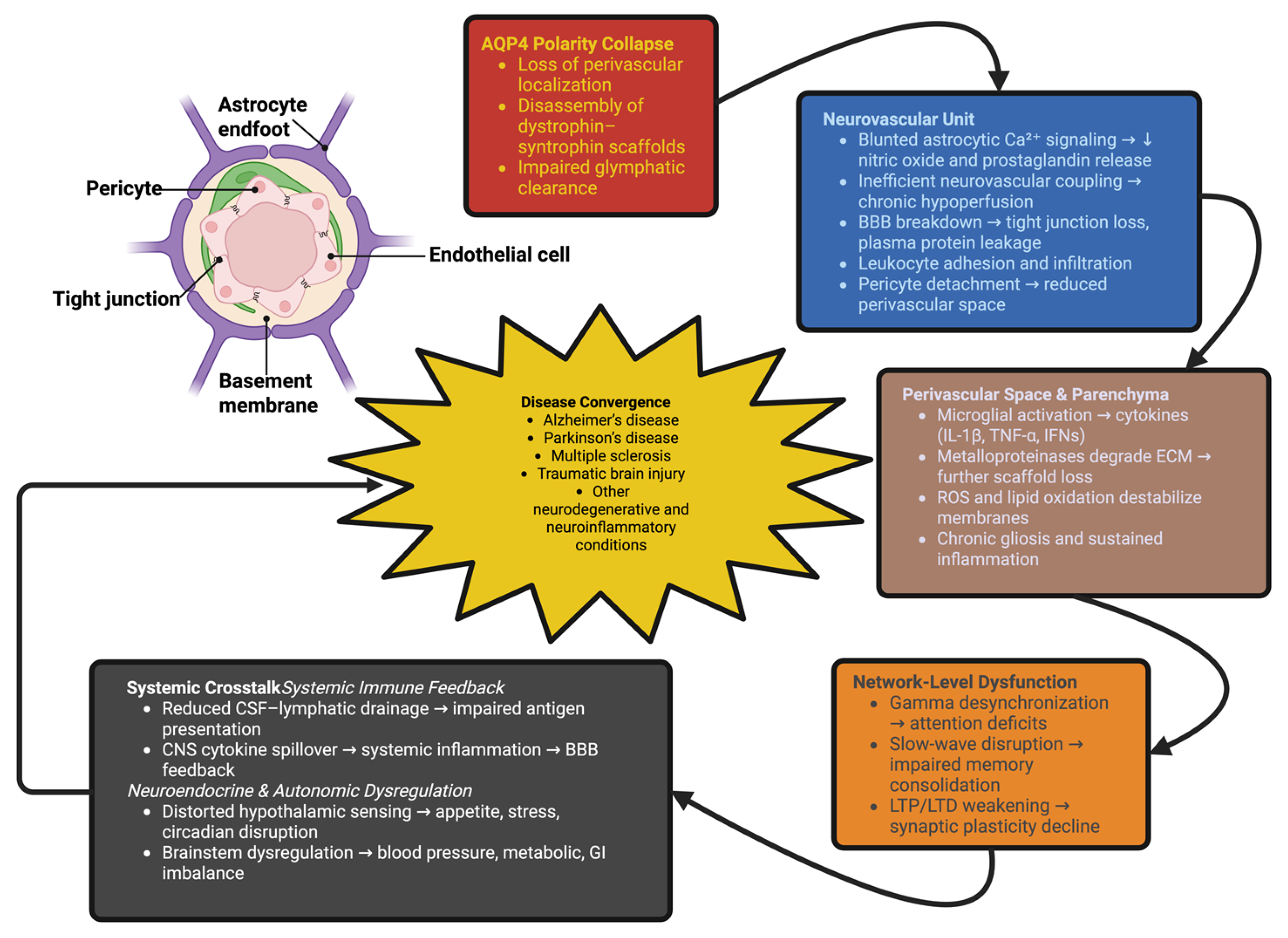

5. Systemic Fallout: How AQP4 Collapse Rewires Brain Pathophysiology

5.1. Neurovascular and Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown: From Local Instability to Systemic Dysfunction

5.2. Immune Activation, Ionic Collapse, and Network Instability

5.3. Convergence Toward Disease: Shared Logic Across Disorders

5.4. Conclusions of Section 5

6. From Collapse to Cascade: Pathological Consequences and Disease Amplification

6.1. From Clearance Failure to System-Wide Amplification

6.2. Disease-Specific Patterns and Nonlinear Dynamics

6.3. Conclusions of Section 6

7. Therapeutic Frontiers: Restoring Polarity and Rebuilding Glymphatic Function

7.1. Rebuilding the Polarity Machinery: Molecular and Genetic Strategies

7.2. Reprogramming Astrocytic States: Transcriptional, Epigenetic, and RNA-Based Modulation

7.3. Targeted Delivery and Microenvironment Engineering: Nanomedicine and Biomaterials

7.4. Modulating the Inflammatory–Vascular Axis: Neuroimmune and Bioelectronic Therapies

7.5. Precision Polarity Medicine: AI, Multi-Omics, and Clinical Translation

7.6. Conclusions of Section 7

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives: Toward a New Era of Fluidic Neurobiology

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbrescia, P.; Signorile, G.; Valente, O.; Palazzo, C.; Cibelli, A.; Nicchia, G.P.; Frigeri, A. Crucial role of Aquaporin-4 extended isoform in brain water Homeostasis and Amyloid-β clearance: Implications for Edema and neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidoryk-Węgrzynowicz, M.; Adamiak, K.; Strużyńska, L. Targeting Protein Misfolding and Aggregation as a Therapeutic Perspective in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Muñoz-Castro, C.; Jaisa-aad, M.; Healey, M.A.; Welikovitch, L.A.; Jayakumar, R.; Bryant, A.G.; Noori, A.; et al. Astrocyte transcriptomic changes along the spatiotemporal progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 2384–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.-J.; Galazyuk, A.V. Depolarization shift in the resting membrane potential of inferior colliculus neurons explains their hyperactivity induced by an acoustic trauma. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1258349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkar, A.; Khan, F.; Goenka, A.; Rajendran, R.L.; Dmello, C.; Hong, C.M.; Mubin, N.; Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.-C. Smart Nanoscale Extracellular Vesicles in the Brain: Unveiling their Biology, Diagnostic Potential, and Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 6709–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleetwood, S.K.; Kleiman, M.; French, V.; Kaschuk, J.; Foster, E.J. Bioinspired waterproof, breathable materials: How does nature transport water across its surfaces and through its membranes? Prog. Mater. Sci. 2026, 156, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Salmon, M.; Guille, N.; Boulay, A.-C. Development of perivascular astrocyte processes. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1585340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hablitz, L.M.; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System: A Novel Component of Fundamental Neurobiology. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 7698–7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, C.N.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Gurau, G.; Mehedinti, M.C. Variations of VEGFR2 Chemical Space: Stimulator and Inhibitory Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H. The circadian rhythms regulated by Cx43-signaling in the pathogenesis of Neuromyelitis Optica. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1021703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.R.; Rajan, K.C.; Blanks, A.; Li, Y.; Prieto, M.C.; Meadows, S.M. Endothelial cell polarity and extracellular matrix composition require functional ATP6AP2 during developmental and pathological angiogenesis. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e154379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaconis, A.; Molinari, F.; Fusco, R.; Di Paola, R. Mitochondria as a Disease-Relevant Organelle in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Key Breakout in Fight Against the Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza-Menchaca, T.; Albores-Medina, A.; Heredia-Mendez, A.J.; Ruíz-May, E.; Ricaño-Rodríguez, J.; Gallegos-García, V.; Esquivel, A.; Vettoretti-Maldonado, G.; Campos-Parra, A.D. Revisiting Epigenetics Fundamentals and Its Biomedical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, P.K. Cellular changes at the glia-neuro-vascular interface in definite idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 981399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, V.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Systemic Neurodegeneration and Brain Aging: Multi-Omics Disintegration, Proteostatic Collapse, and Network Failure Across the CNS. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnulfo, G.; Wang, S.H.; Myrov, V.; Toselli, B.; Hirvonen, J.; Fato, M.M.; Nobili, L.; Cardinale, F.; Rubino, A.; Zhigalov, A.; et al. Long-range phase synchronization of high-frequency oscillations in human cortex. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa-Kawada, J.; Kinoshita-Kawada, M.; Hiramoto, M.; Yamagishi, S.; Mishima, T.; Yasunaga, S.; Tsuboi, Y.; Hattori, N.; Wu, J.Y. Neuronal guidance signaling in neurodegenerative diseases: Key regulators that function at neuron-glia and neuroimmune interfaces. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 21, 612–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Eva, L.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Han, Y.; Lv, P.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Ma, Z.; Xia, T.; Zhang, B.; et al. Long-term isoflurane anesthesia induces cognitive deficits via AQP4 depolarization mediated blunted glymphatic inflammatory proteins clearance. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2024, 44, 1450–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, J.-L. Translating Alzheimer’s Disease Mechanisms into Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedde, M.; Piazza, F.; Pascarella, R. Traumatic Brain Injury and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Not Only Trigger for Neurodegeneration but Also for Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy? Biomedicines 2025, 13, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, P.M.; Banerjee, A.; Ghosal, A.; Layek, B. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Munteanu, O.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V.; Enyedi, M. Decoding Neurodegeneration: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekala, A.; Qiu, H. Interplay Between Vascular Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Pathology: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Management. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi, J. Astrocytes: News about Brain Health and Diseases. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Kim, M.; Park, W.; Lim, J.S.; Lee, E.; Cha, H.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, S.H.; Park, J.E.; et al. Upregulation of AQP4 Improves Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity and Perihematomal Edema Following Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 2692–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patabendige, A.; Chen, R. Astrocytic aquaporin 4 subcellular translocation as a therapeutic target for cytotoxic edema in ischemic stroke. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 2666–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslesh, T.; Al-aghbari, A.; Yokota, T. Assessing the Role of Aquaporin 4 in Skeletal Muscle Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, C.M.; Lima Verde, M.E.; Silva-Sousa, A.C.; Mansoorifar, A.; Athirasala, A.; Subbiah, R.; Tahayeri, A.; Sousa, M.; Fraga, M.A.; Visalakshan, R.M.; et al. Perivascular cells function as key mediators of mechanical and structural changes in vascular capillaries. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadp3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.; Abbrescia, P.; Valente, O.; Nicchia, G.P.; Banitalebi, S.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Trojano, M.; Frigeri, A. Tissue Distribution of the Readthrough Isoform of AQP4 Reveals a Dual Role of AQP4ex Limited to CNS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoy, S.; Liu, J. Regulation of Protein Synthesis at the Translational Level: Novel Findings in Cardiovascular Biology. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Persyn, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ulloa-Montoya, F.; Cenik, C.; Agarwal, V. Predicting the translation efficiency of messenger RNA in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasian, V.; Davoudi, S.; Vahabzadeh, A.; Maftoon-Azad, M.J.; Janahmadi, M. Astroglial Kir4.1 and AQP4 Channels: Key Regulators of Potassium Homeostasis and Their Implications in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markou, A.; Kitchen, P.; Aldabbagh, A.; Repici, M.; Salman, M.M.; Bill, R.M.; Balklava, Z. Mechanisms of aquaporin-4 vesicular trafficking in mammalian cells. J. Neurochem. 2024, 168, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, Z.; Hawley, E.; Hayosh, D.; Webster-Wood, V.A.; Akkus, O. Kinesin and Dynein Mechanics: Measurement Methods and Research Applications. J. Biomech. Eng. 2018, 140, 0208051–02080511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Parets, S.; Fernández-Díaz, J.; Beteta-Göbel, R.; Rodríguez-Lorca, R.; Román, R.; Lladó, V.; Rosselló, C.A.; Fernández-García, P.; Escribá, P.V. Lipids in Pathophysiology and Development of the Membrane Lipid Therapy: New Bioactive Lipids. Membranes 2021, 11, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Tham, D.K.L.; Perronnet, C.; Joshi, B.; Nabi, I.R.; Moukhles, H. The Oxidative Stress-Induced Increase in the Membrane Expression of the Water-Permeable Channel Aquaporin-4 in Astrocytes Is Regulated by Caveolin-1 Phosphorylation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Lopez, T. Peripheral Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: Their Impact on Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity and Glia Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, T.; Cao, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F.; Wang, D. The Role of Methylation Modification in Neural Injury and Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacTaggart, B.; Kashina, A. Posttranslational modifications of the cytoskeleton. Cytoskeleton 2021, 78, 142–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Tai, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Wei, W.; Xiang, Y.K.; Wang, Q. Gα12 and Gα13: Versatility in Physiology and Pathology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 809425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, R.C.; Chang, K.-H.; Vaitinadin, N.-S.; Cancelas, J.A. Rho GTPases control specific cytoskeleton-dependent functions of hematopoietic stem cells. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 256, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirado-García, P.; Ferreiro, A.; González-Alday, R.; Arias-Ramos, N.; Lizarbe, B.; López-Larrubia, P. Aquaporin-4 inhibition alters cerebral glucose dynamics predominantly in obese animals: An MRI study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwecka, N.; Golberg, M.; Świerczewska, D.; Filipek, B.; Pendrasik, K.; Bączek-Grzegorzewska, A.; Stasiołek, M.; Świderek-Matysiak, M. Sleep Disorders in Neurodegenerative Diseases with Dementia: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, A.; Abreu, D.S.; Dias, J.D.; Azenha, P.; Barsanti, S.; Oliveira, J.F. Calcium-Dependent Signaling in Astrocytes: Downstream Mechanisms and Implications for Cognition. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennes, M.; Richter, M.L.; Fischer-Sternjak, J.; Götz, M. Astrocyte diversity and subtypes: Aligning transcriptomics with multimodal perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2025, 26, 4203–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, X.; Fan, J.; Qiao, J.; Mao, F. Cell–cell communication: New insights and clinical implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringe, S.; Hörmann, N.G.; Oberhofer, H.; Reuter, K. Implicit Solvation Methods for Catalysis at Electrified Interfaces. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 10777–10820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Z. Research Progress of Computational Fluid Dynamics in Mixed Ionic–Electronic Conducting Oxygen-Permeable Membranes. Membranes 2025, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, J.W.; Yang, Y.; Scallan, J.P.; Sweat, R.S.; Adderley, S.P.; Murfee, W.L. Lymphatic Vessel Network Structure and Physiology. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 9, 207–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Wang, M.X.; Ismail, O.; Braun, M.; Schindler, A.G.; Reemmer, J.; Wang, Z.; Haveliwala, M.A.; O’Boyle, R.P.; Han, W.Y.; et al. Loss of perivascular aquaporin-4 localization impairs glymphatic exchange and promotes amyloid β plaque formation in mice. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmaati Cherkaoui, M.; Vacca, O.; Izabelle, C.; Boulay, A.-C.; Boulogne, C.; Gillet, C.; Barnier, J.-V.; Rendon, A.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Vaillend, C. Dp71 contribution to the molecular scaffold anchoring aquaporine-4 channels in brain macroglial cells. Glia 2021, 69, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carder, J.D.; Barile, B.; Shisler, K.A.; Pisani, F.; Frigeri, A.; Hipps, K.W.; Nicchia, G.P.; Brozik, J.A. Thermodynamics and S-Palmitoylation Dependence of Interactions between Human Aquaporin-4 M1 Tetramers in Model Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choubey, P.K.; Roy, J.K. Rab11, a vesicular trafficking protein, affects endoreplication through Ras-mediated pathway in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 367, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, M.; Tekin, S.; Gamal, M.; Khafaga, N.; Çelebi, F.; Tarantino, G. Lipid rafts: Novel therapeutic targets for metabolic, neurodegenerative, oncological, and cardiovascular diseases. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, K.; Silagi, E.S.; Choi, H.; Sakabe, K.; Mochida, J.; Shapiro, I.M.; Risbud, M.V. Circadian factors BMAL1 and RORα control HIF-1α transcriptional activity in nucleus pulposus cells: Implications in maintenance of intervertebral disc health. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 23056–23071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, L.M.; de Azevedo, A.L.K.; Carvalho, T.M.; Resende, J.; Magno, J.M.; Figueiredo, B.C.; Malta, T.M.; Castro, M.A.A.; Cavalli, L.R. Identification of Epigenetic Regulatory Networks of Gene Methylation–miRNA–Transcription Factor Feed-Forward Loops in Basal-like Breast Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Dermardirossian, C. GEF-H1: Orchestrating the interplay between cytoskeleton and vesicle trafficking. Small GTPases 2013, 4, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, L.; Jakus, Z. Mechanosensation and Mechanotransduction by Lymphatic Endothelial Cells Act as Important Regulators of Lymphatic Development and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarskaite, L.; Bjørnstad, D.M.; Pettersen, K.H.; Cunen, C.; Hermansen, G.H.; Åbjørsbråten, K.S.; Chambers, A.R.; Sprengel, R.; Vervaeke, K.; Tang, W.; et al. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling is reduced during sleep and is involved in the regulation of slow wave sleep. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Thomas, R.J.; Liu, Y.; Shea, S.A.; Lu, J.; Peng, C.-K. Slow wave synchronization and sleep state transitions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarskaite, L.; Nafari, S.; Ravnanger, A.K.; Frey, M.M.; Skauli, N.; Åbjørsbråten, K.S.; Roth, L.C.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Nagelhus, E.A.; Ottersen, O.P.; et al. Role of aquaporin-4 polarization in extracellular solute clearance. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.M.; Zohoorian, N.; Skauli, N.; Ottersen, O.P.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M. Are diurnal variations in glymphatic clearance driven by circadian regulation of Aquaporin-4 expression? Fluids Barriers CNS 2025, 22, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Precision Neuro-Oncology in Glioblastoma: AI-Guided CRISPR Editing and Real-Time Multi-Omics for Genomic Brain Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosic, B.; Dukefoss, D.B.; Åbjørsbråten, K.S.; Tang, W.; Jensen, V.; Ottersen, O.P.; Enger, R.; Nagelhus, E.A. Aquaporin-4-independent volume dynamics of astroglial endfeet during cortical spreading depression. Glia 2019, 67, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.-M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Aljboor, G.S.; Gorgan, R.M. Stroke and Pulmonary Thromboembolism Complicating a Kissing Aneurysm in the M1 Segment of the Right MCA. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobral, A.F.; Costa, I.; Teixeira, V.; Silva, R.; Barbosa, D.J. Molecular Motors in Blood–Brain Barrier Maintenance by Astrocytes. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Glavan, L.-A.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Ilie, M.-M.; Gorgan, R.M. Navigating the Rare and Dangerous: Successful Clipping of a Superior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysm Against the Odds of Uncontrolled Hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tao, W. Microenvironmental Variations After Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 750810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryka-Marton, M.; Grabowska, A.D.; Szukiewicz, D. Breaking the Barrier: The Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines in BBB Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chu, J.M.-T.; Wong, G.T.-C.; Chang, R.C.-C. Complement C3 From Astrocytes Plays Significant Roles in Sustained Activation of Microglia and Cognitive Dysfunctions Triggered by Systemic Inflammation After Laparotomy in Adult Male Mice. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2024, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, J.-S.; Kim, R. Peripheral blood inflammatory cytokines in prodromal and overt α-synucleinopathies: A review of current evidence. Encephalitis 2023, 3, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. Comprehensive Management of a Giant Left Frontal AVM Coexisting with a Bilobed PComA Aneurysm: A Case Report Highlighting Multidisciplinary Strategies and Advanced Neurosurgical Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, J.M.; Lam, C.; Rossi, A.; Gupta, T.; Bennett, J.L.; Verkman, A.S. Binding Affinity and Specificity of Neuromyelitis Optica Autoantibodies to Aquaporin-4 M1/M23 Isoforms and Orthogonal Arrays. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16516–16524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Toader, C.; Rădoi, M.P.; Șerban, M. Precision Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury: Integrating CRISPR Technologies, AI-Driven Therapeutics, Single-Cell Omics, and System Neuroregeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallese, F.; Maso, L.; Giamogante, F.; Poggio, E.; Barazzuol, L.; Salmaso, A.; Lopreiato, R.; Cendron, L.; Navazio, L.; Zanni, G.; et al. The ataxia-linked E1081Q mutation affects the sub-plasma membrane Ca2+-microdomains by tuning PMCA3 activity. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugar, S.S.; Heyob, K.M.; Cheng, X.; Lee, R.J.; Rogers, L.K. Perinatal inflammation alters histone 3 and histone 4 methylation patterns: Effects of MiR-29b supplementation. Redox Biol. 2021, 38, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffan, D.; Pezzini, C.; Esposito, M.; Franco-Romero, A. Mitochondrial Aging in the CNS: Unravelling Implications for Neurological Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X. Progress in Understanding Oxidative Stress, Aging, and Aging-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ita, J.R.; Castilla-Cortázar, I.; Aguirre, G.A.; Sánchez-Yago, C.; Santos-Ruiz, M.O.; Guerra-Menéndez, L.; Martín-Estal, I.; García-Magariño, M.; Lara-Díaz, V.J.; Puche, J.E.; et al. Altered liver expression of genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism in mice with partial IGF-1 deficiency: An experimental approach to metabolic syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęśko, H.; Stępień, A.; Lukiw, W.J.; Strosznajder, R.P. The Cross-Talk Between Sphingolipids and Insulin-Like Growth Factor Signaling: Significance for Aging and Neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 3501–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachfalska, N.; Putowski, Z.; Krzych, Ł.J. Distant Organ Damage in Acute Brain Injury. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Costin, H.P.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Glavan, L.-A.; Gorgan, R.M. Cerebellar Cavernoma Resection: Case Report with Long-Term Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltran-Velasco, A.I.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Impact of Peripheral Inflammation on Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Its Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, M.A.; Pedroni, V.I. Role of Lipid Composition on the Mechanical and Biochemical Vulnerability of Myelin and Its Implications for Demyelinating Disorders. Biophysica 2025, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onigbinde, S.; Adeniyi, M.; Daramola, O.; Chukwubueze, F.; Bhuiyan, M.M.A.A.; Nwaiwu, J.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Mechref, Y. Glycomics in Human Diseases and Its Emerging Role in Biomarker Discovery. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, S.; Brimberg, L. Aquaporin-4 Water Channel in the Brain and Its Implication for Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Dobrin, N.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Munteanu, O. Complex Anatomy, Advanced Techniques: Microsurgical Clipping of a Ruptured Hypophyseal Artery Aneurysm. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.-P.; Xu, J.; Zhuo, F.; Sun, S.-Q.; Liu, H.; Yang, M.; Huang, J.; Lu, W.-T.; Huang, S.-Q. Loss of AQP4 polarized localization with loss of β-dystroglycan immunoreactivity may induce brain edema following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 588, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Costin, H.P.; Ilie, M.-M.; Popa, A.A.; Gorgan, R.M. Single-Stage Microsurgical Clipping of Multiple Intracranial Aneurysms in a Patient with Cerebral Atherosclerosis: A Case Report and Review of Surgical Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Collapse of Brain Clearance: Glymphatic-Venous Failure, Aquaporin-4 Breakdown, and AI-Empowered Precision Neurotherapeutics in Intracranial Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestre, H.; Tithof, J.; Du, T.; Song, W.; Peng, W.; Sweeney, A.M.; Olveda, G.; Thomas, J.H.; Nedergaard, M.; Kelley, D.H. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daversin-Catty, C.; Gjerde, I.G.; Rognes, M.E. Geometrically Reduced Modelling of Pulsatile Flow in Perivascular Networks. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 882260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Ruptured Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysms: Integrating Microsurgical Expertise, Endovascular Challenges, and AI-Driven Risk Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, C.; Hao, X. Deciphering aquaporin-4′s influence on perivascular diffusion indices using DTI in rat stroke studies. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1566957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shentu, W.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Lai, Q.; Xu, Q.; Qiao, S. Functional abnormalities of the glymphatic system in cognitive disorders. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 3430–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, L.A.; Heys, J.J. Fluid Flow and Mass Transport in Brain Tissue. Fluids 2019, 4, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, D.; Kameda, H.; Kinota, N.; Fujii, T.; Xiawei, B.; Simi, Z.; Takai, Y.; Chau, S.; Miyasaka, Y.; Mashimo, T.; et al. Loss of aquaporin-4 impairs cerebrospinal fluid solute clearance through cerebrospinal fluid drainage pathways. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Marrero, I.; Hernández-Abad, L.G.; González-Gómez, M.; Soto-Viera, M.; Carmona-Calero, E.M.; Castañeyra-Ruiz, L.; Castañeyra-Perdomo, A. Altered Expression of AQP1 and AQP4 in Brain Barriers and Cerebrospinal Fluid May Affect Cerebral Water Balance during Chronic Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladky, S.B.; Barrand, M.A. Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: Evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS 2014, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo-Contreras, J.L.; Ramírez-Lorca, R.; Villadiego, J.; Echevarría, M. Cellular Distribution of Brain Aquaporins and Their Contribution to Cerebrospinal Fluid Homeostasis and Hydrocephalus. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Ríos, C.A.; Leon-Rojas, J.E. Aquaporin-4 in Stroke and Brain Edema—Friend or Foe? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, L.; Iliff, J.J.; Heys, J.J. Analysis of convective and diffusive transport in the brain interstitium. Fluids Barriers CNS 2019, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Microglial lactate metabolism as a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, S.; Carstens, K.; Dewing, W.; Fiacco, T.A. Astrocyte regulation of extracellular space parameters across the sleep-wake cycle. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1401698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaman, B.A.; Zhang, Y.; Matosevich, N.; Kjærby, C.; Foustoukos, G.; Andersen, M.; Eban-Rothschild, A. Emerging Functions of Neuromodulation during Sleep. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e1277242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rábago-Monzón, Á.R.; Osuna-Ramos, J.F.; Armienta-Rojas, D.A.; Camberos-Barraza, J.; Camacho-Zamora, A.; Magaña-Gómez, J.A.; De la Herrán-Arita, A.K. Stress-Induced Sleep Dysregulation: The Roles of Astrocytes and Microglia in Neurodegenerative and Psychiatric Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, A.W.C.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, N.; Li, H. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase in the Perivascular Adipose Tissue. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.-D.; Kuo, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Kim, C.-H. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in the Pathogenesis of Epithelial Differentiation, Vascular Disease, Endometriosis, and Ocular Fibrotic Pterygium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.M.; Radoi, M.P.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Serban, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. Challenging Management of a Rare Complex Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation in the Corpus Callosum and Post-Central Gyrus: A Case Study of a 41-Year-Old Female. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.; Gharagozloo, M.; Simard, C.; Gris, D. Astrocytes Maintain Glutamate Homeostasis in the CNS by Controlling the Balance between Glutamate Uptake and Release. Cells 2019, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Calvo, A.; Biviano, M.D.; Christensen, A.H.; Katifori, E.; Jensen, K.H.; Ruiz-García, M. The fluidic memristor as a collective phenomenon in elastohydrodynamic networks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. Fluid transport in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1025–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Eva, L.; Costea, D.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dumitru, A.V. Large Pontine Cavernoma with Hemorrhage: Case Report on Surgical Approach and Recovery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDade, E.M.; Barthélemy, N.R.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Gordon, B.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Clifford, D.; Goate, A.M.; Renton, A.E.; et al. The relationship of soluble tau species with Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaque removal and tau pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, K.N.; Lilius, T.; Rosenholm, M.; Sigurðsson, B.; Kelley, D.H.; Nedergaard, M. Perivascular cerebrospinal fluid inflow matches interstitial fluid efflux in anesthetized rats. iScience 2025, 28, 112323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, A. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Distinct CSF α-synuclein aggregation profiles associated with Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes and MCI-to-AD conversion. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyckenvik, T.; Olsson, M.; Forsberg, M.; Wasling, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Hedner, J.; Hanse, E. Sleep reduces CSF concentrations of beta-amyloid and tau: A randomized crossover study in healthy adults. Fluids Barriers CNS 2025, 22, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicki, M.; Karuga, F.F.; Szmyd, B.; Sochal, M.; Gabryelska, A. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Circadian Clock Disruption, and Metabolic Consequences. Metabolites 2023, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.A.; Lennon, R.; Greenhalgh, A.D. Basement membranes’ role in immune cell recruitment to the central nervous system. J. Inflamm. 2024, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse, T.L.; Mishra, A. Neurovascular Coupling in Development and Disease: Focus on Astrocytes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 702832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovkin, S.; Kozinov, E.; Ivanchenko, M.; Gordleeva, S. Controlling synchronization of gamma oscillations by astrocytic modulation in a model hippocampal neural network. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, F.-Y.; Yen, Y. Imaging biomarkers for clinical applications in neuro-oncology: Current status and future perspectives. Biomark. Res. 2023, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.-J.; Zhang, H.; Binder, D.K.; Verkman, A.S. Aquaporin-4–dependent K+ and water transport modeled in brain extracellular space following neuroexcitation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2013, 141, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugler, E.C.; Greenwood, J.; MacDonald, R.B. The “Neuro-Glial-Vascular” Unit: The Role of Glia in Neurovascular Unit Formation and Dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 732820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Li, N.; Cao, X.; Qin, W.; Huang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Chen, G.; et al. More severe vascular remodeling in deep brain regions caused by hemodynamic differences is a potential mechanism of hypertensive cerebral small vessel disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2025, 45, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.R.; Simovic Markovic, B.; Fellabaum, C.; Arsenijevic, A.; Djonov, V.; Volarevic, V. Molecular mechanisms underlying therapeutic potential of pericytes. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Intestinal barrier permeability: The influence of gut microbiota, nutrition, and exercise. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1380713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, D.; Dobrin, N.; Tataru, C.-I.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Munteanu, O.; Diaconescu, I.B. The Glymphatic–Venous Axis in Brain Clearance Failure: Aquaporin-4 Dysfunction, Biomarker Imaging, and Precision Therapeutic Frontiers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifa, A.E.; Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Odum, J.; Shunnarah, J.G.; Austin, N.; Kaddoumi, A. Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms and Targeted Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, S.O.; Greiner, T.; Joost, S.; Amor, S.; Valk, P.V.D.; Schmitz, C.; Kipp, M. Aquaporin-4 Expression during Toxic and Autoimmune Demyelination. Cells 2020, 9, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermair, A.L.; Munz, M.; Schaich, A.; Nitsche, S.; Willenborg, B.; Muñoz Venegas, L.M.; Willenborg, C.; Schunkert, H.; Schweiger, U.; Erdmann, J. Association of Genetic Variation at AQP4 Locus with Vascular Depression. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkoris, S.; Vrettou, C.S.; Lotsios, N.S.; Issaris, V.; Keskinidou, C.; Papavassiliou, K.A.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Kotanidou, A.; Dimopoulou, I.; Vassiliou, A.G. Aquaporins in Acute Brain Injury: Insights from Clinical and Experimental Studies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogensen, F.L.-H.; Delle, C.; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System (En)during Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Pacheco, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Rosa, C.C.-D.L.; Ramirez-Acuña, J.M.; Perez-Romero, B.A.; Guerrero-Rodriguez, J.F.; Martinez-Avila, N.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. The Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S.; Müller, V. The dual nature of neuroinflammation in networked brain. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1659947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, N.; Giovenzana, M.; Misztak, P.; Mingardi, J.; Musazzi, L. Glutamate-Mediated Excitotoxicity in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurodevelopmental and Adult Mental Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Redox Revolution in Brain Medicine: Targeting Oxidative Stress with AI, Multi-Omics and Mitochondrial Therapies for the Precision Eradication of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Di Minno, A.; Santarcangelo, C.; Khan, H.; Daglia, M. Improvement of Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction by β-Caryophyllene: A Focus on the Nervous System. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioni, A.; Martorana, A.; Santarnecchi, E.; Hampel, H.; Koch, G. The neurobiological foundation of effective repetitive transcranial magnetic brain stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Aljboor, G.S.; Gorgan, R.M. The Management of a Giant Convexity en Plaque Anaplastic Meningioma with Gerstmann Syndrome: A Case Report of Surgical Outcomes in a 76-Year-Old Male. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitpass Romero, K.; Stevenson, T.J.; Smyth, L.C.D.; Watkin, B.; McCullough, S.J.C.; Vinnell, L.; Smith, A.M.; Schweder, P.; Correia, J.A.; Kipnis, J.; et al. Age-related meningeal extracellular matrix remodeling compromises CNS lymphatic function. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchioni, D.; Özbay, P.S.; Mandelkow, H.; de Zwart, J.A.; Wang, Y.; van Gelderen, P.; Duyn, J.H. Autonomic arousals contribute to brain fluid pulsations during sleep. NeuroImage 2022, 249, 118888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Serban, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Enyedi, M. Revolutionizing Neuroimmunology: Unraveling Immune Dynamics and Therapeutic Innovations in CNS Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Dai, Y.; Hu, C.; Lin, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of the blood–brain barrier dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Lin, W.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Q.; He, B.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Pei, Z.; Su, H.; Yao, X. Alterations in AQP4 expression and polarization in the course of motor neuron degeneration in SOD1G93A mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, T.; Mirzapourshafiyi, F.; Barbacena, P.; Riddell, M.; Pasha, A.; Li, M.; Kawamura, T.; Brandes, R.P.; Hirose, T.; Ohno, S.; et al. PAR-3 controls endothelial planar polarity and vascular inflammation under laminar flow. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e45253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrión, O.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Padilla-Godínez, F.J.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Manjarrez, E. α-Synuclein Pathology in Synucleinopathies: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currais, A.; Fischer, W.; Maher, P.; Schubert, D. Intraneuronal protein aggregation as a trigger for inflammation and neurodegeneration in the aging brain. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2017, 31, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Li, P.; Liu, H.; Prokosch, V. Oxidative Stress, Vascular Endothelium, and the Pathology of Neurodegeneration in Retina. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, B.Y.A.; Pallier, P.N.; Jenkins, S.I.; Chen, R. Hypoxic Neuroinflammation in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahsavani, N.; Kataria, H.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Mechanisms and repair strategies for white matter degeneration in CNS injury and diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feofilaktova, T.; Kushnireva, L.; Segal, M.; Korkotian, E. Calcium signaling in postsynaptic mitochondria: Mechanisms, dynamics, and role in ATP production. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1621070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, I.F.; Ismail, O.; Machhada, A.; Colgan, N.; Ohene, Y.; Nahavandi, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Fisher, A.; Meftah, S.; Murray, T.K.; et al. Impaired glymphatic function and clearance of tau in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Brain J. Neurol. 2020, 143, 2576–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladky, S.B.; Barrand, M.A. Regulation of brain fluid volumes and pressures: Basic principles, intracranial hypertension, ventriculomegaly and hydrocephalus. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayata, C.; Lauritzen, M. Spreading Depression, Spreading Depolarizations, and the Cerebral Vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 953–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K. Multifaceted Roles of Aquaporins in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Rout, S.; Deep, P.; Sahu, C.; Samal, P.K. The Dual Role of Astrocytes in CNS Homeostasis and Dysfunction. Neuroglia 2025, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.; Buccoliero, C.; Mola, M.G.; Abbrescia, P.; Nicchia, G.P.; Trojano, M.; Frigeri, A. AQP4ex is crucial for the anchoring of AQP4 at the astrocyte end-feet and for neuromyelitis optica antibody binding. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skauli, N.; Savchenko, E.; Ottersen, O.P.; Roybon, L.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M. Canonical Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling Regulates Expression of Aquaporin-4 and Its Anchoring Complex in Mouse Astrocytes. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 878154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hua, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Engineering Targeted Gene Delivery Systems for Primary Hereditary Skeletal Myopathies: Current Strategies and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momotyuk, E.; Ebrahim, N.; Shakirova, K.; Dashinimaev, E. Role of the cytoskeleton in cellular reprogramming: Effects of biophysical and biochemical factors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1538806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.-M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Glavan, L.-A.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. The Microsurgical Resection of an Arteriovenous Malformation in a Patient with Thrombophilia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Anatomy-Guided Microsurgical Resection of a Dominant Frontal Lobe Tumor Without Intraoperative Adjuncts: A Case Report from a Resource-Limited Context. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, J.; Yamazaki, T.; Funakoshi, H. Toward the Development of Epigenome Editing-Based Therapeutics: Potentials and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Geng, L.; Yang, J. The role of transcriptional and epigenetic modifications in astrogliogenesis. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Rashad, I.; Egbon, E.; Teke, J.; Ovsepian, S.V.; Boussios, S. Reversing Epigenetic Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanistic and Therapeutic Considerations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-H.; Nichols, J.G.; Hsu, C.-W.; Vickers, T.A.; Crooke, S.T. mRNA levels can be reduced by antisense oligonucleotides via no-go decay pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6900–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Butt, A.; Li, B.; Illes, P.; Zorec, R.; Semyanov, A.; Tang, Y.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocytes in human central nervous system diseases: A frontier for new therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D. RNA in Therapeutics: CRISPR in the Clinic. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Cao, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; Yu, H.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Dystrophin 71 deficiency causes impaired aquaporin-4 polarization contributing to glymphatic dysfunction and brain edema in cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 199, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageeva, T.; Rizvanov, A.; Mukhamedshina, Y. NF-κB and JAK/STAT Signaling Pathways as Crucial Regulators of Neuroinflammation and Astrocyte Modulation in Spinal Cord Injury. Cells 2024, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wautier, J.-L.; Wautier, M.-P. Endothelial Cell Participation in Inflammatory Reaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groten, S.A.; Smit, E.R.; Janssen, E.F.J.; van den Eshof, B.L.; van Alphen, F.P.J.; van der Zwaan, C.; Meijer, A.B.; Hoogendijk, A.J.; van den Biggelaar, M. Multi-omics delineation of cytokine-induced endothelial inflammatory states. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Chang, Y.-C.; Zafeiropoulos, S.; Nassrallah, Z.; Miller, L.; Zanos, S. Strategies for precision vagus neuromodulation. Bioelectron. Med. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Sato-Numata, K. Optogenetic and Endogenous Modulation of Ca2+ Signaling in Schwann Cells: Implications for Autocrine and Paracrine Neurotrophic Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.; Snyder, M. Multi-Omics Profiling for Health. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2023, 22, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloiu, A.I.; Filipoiu, F.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Munteanu, O.; Serban, M. Sphenoid sinus hyperpneumatization: Anatomical variants, molecular blueprints, and AI-augmented roadmaps for skull base surgery. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1634206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, J.; Munir, U.; Nori, A.; Williams, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, e188–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklu, A.; Ohayon, D.; Wustoni, S.; Druet, V.; Saleh, A.; Inal, S. Organic Bioelectronic Devices for Metabolite Sensing. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 4581–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Blueprint of Collapse: Precision Biomarkers, Molecular Cascades, and the Engineered Decline of Fast-Progressing ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Herrero, B.; Armenia, I.; Ortiz, C.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Betancor, L.; Grazú, V. Opportunities for nanomaterials in enzyme therapy. J. Control. Release 2024, 372, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, E.; Tajiknia, V.; Shamsaki, N.; Naderi-Taheri, M.; Aschner, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Tamtaji, O.R. Aquaporin 4 and brain-related disorders: Insights into its apoptosis roles. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regulatory Domain | Fundamental Role | Principal Components | Characteristic Disruptions | Indicative Measurements | Intervention Strategies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perivascular Anchoring Complex | Secures AQP4 at astrocytic endfeet through ECM–DAPC linkage. | α-Syntrophin, Dp71, β-Dystroglycan, Agrin | Mislocalization; reduced perivascular density; impaired CSF–ISF coupling. | Endfoot AQP4/parenchymal AQP4 ratio; ECM marker profiling. | Scaffold-reinforcing peptides; agrin-based stabilization. | [51,52] |

| Isoform Configuration & OAP Formation | Determines lattice assembly and water permeability efficiency. | AQP4-M1/M23 isoforms; phosphorylation regulators | Loss of OAPs; diffuse membrane distribution; slowed clearance. | OAP structural assays; intrathecal tracer kinetics. | Isoform ratio modulators; OAP-stabilizing compounds. | [1,53] |

| Trafficking & Endfoot Targeting | Directs AQP4 vesicles to perivascular domains. | Rab11, Microtubules, Kinesin/Dynein motors | Endfoot delivery failure; ectopic accumulation near synapses. | Vesicle-targeting markers; Rab11 localization indices. | Vesicular routing enhancers; PDZ signal modifiers. | [54] |

| Membrane Microdomain Organization | Maintains localized AQP4 clusters within lipid-ordered zones. | Caveolin-1, Sphingolipids, Kir4.1 | Increased lateral mobility; disrupted K+–water coupling. | Membrane order imaging; Kir4.1/AQP4 colocalization. | Lipid microdomain regulators; Kir4.1 co-support. | [55] |

| Transcriptional & Epigenetic Regulation | Controls Aqp4 transcription, rhythmicity, and inflammatory responsiveness. | HIF-1α, NF-κB, BMAL1, microRNAs | Aberrant expression; circadian flattening; edema susceptibility. | Transcript levels; circulating miRNA signatures. | Epigenetic modifiers; circadian-aligned dosing. | [56,57] |

| Cytoskeletal Integration | Supports structural stability and vesicle docking at endfeet. | GFAP, RhoA, CaMKII | Reactive gliosis; disrupted anchoring geometry; impaired trafficking. | CSF GFAP; actin remodeling assays. | Gliosis-modulating agents; cytoskeletal stabilizers. | [58] |

| Vascular & Mechanical Signaling | Aligns polarity with pulsatility, endothelial cues, and flow dynamics. | Pericytes, Piezo channels, eNOS | Polarity loss with vascular stiffening; reduced hydraulic coupling. | Perivascular MRI; vascular compliance metrics. | Vascular-compliance therapies; mechanosensitive stimuli. | [59] |

| Sleep–Wake Modulation | Enhances AQP4 clustering and clearance during low-NE sleep states. | β-Adrenergic receptors, cAMP | Reduced nocturnal clustering; impaired diurnal clearance. | Sleep-locked tracer clearance; EEG-linked flow metrics. | Slow-wave enhancement; chronotherapeutic timing. | [60,61] |

| Systems Level Integration | Maintains stability across interacting polarity modules. | Cross-module interactions | Threshold-dependent collapse; nonlinear transition to global depolarization. | Composite polarity indices; multi-parametric modeling. | Early multi-target intervention; staged restoration paradigms. | [15] |

| Functional Axis | Physiological Contribution | Consequences of Polarity Loss | Indicative Measurements | Intervention Angles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Coupling | Converts arterial pulsatility into directed CSF transit along perivascular channels, supporting fluid exchange with parenchyma. | Fragmented flow pathways; reduced hydraulic reach; inefficient mechanotransduction by astrocytes and perivascular cells. | Attenuated influx waveforms on dynamic MRI; altered cerebrovascular reactivity profiles; NO-related metabolic signatures. | Reinforcement of perivascular ECM; stabilization of dystrophin-associated anchoring complexes; vascular compliance optimization. | [93,116] |

| Bulk Clearance and Proteostasis | Removes macromolecules through convection-dominant transport, maintaining extracellular compositional stability. | Collapse into diffusion-dominant kinetics; retention of misfolded proteins; ECM softening and secondary inflammatory remodeling. | CSF protein spectra (Aβ, tau, α-syn); neuroinflammatory PET markers; lactate and metabolite accumulation. | Modulators of AQP4 clustering; proteostasis-enhancing compounds; oxidative-stress attenuation. | [117,118] |

| Rhythmic Fluid Regulation | Aligns glymphatic activity with sleep–wake cycles, enhancing nocturnal solute turnover. | Blunted circadian variation; impaired adenosine dynamics; persistent adrenergic suppression of perivascular channel clustering. | Flattened diurnal solute oscillation curves; sleep–EEG architecture deviations; metabolic neuromodulator assays. | Circadian-phase–specific treatment; modulation of arousal circuits; stabilization of sleep-dependent clearance. | [119] |

| Perivascular Structural Homeostasis | Preserves basement membrane composition, vascular pliability, and controlled entry of immune mediators. | ECM thickening; pericyte dysregulation; low-grade vascular inflammation; increased paracellular permeability. | MMP activity assays; PDGFRβ release; GFAP/S100B elevation; MRI permeability shifts. | ECM remodeling strategies; pericyte-state modulators; endothelial–astrocyte communication repair. | [29,120] |

| Ion and Neurovascular Microdomain Coordination | Maintains spatiotemporal K+/glutamate control and couples neural activity to vascular adjustments. | Accumulation of excitatory ions; pH microdomain instability; impaired K+–NO–vascular feedback loops. | Extracellular ion and pH mapping; delayed hemodynamic response signals; vasoreactivity quantification. | Targeted ionic-buffering approaches; NO-pathway reinforcement; pH-stabilizing interventions. | [121] |

| Network-Level Integration | Stabilizes the extracellular milieu needed for synchronous oscillations and long-range neural communication. | Volatile extracellular volume; dampened gamma coherence; disrupted slow-wave organization; compromised network controllability. | EEG coherence metrics; functional connectivity MRI; computational control network indices. | Closed-loop neuromodulation; metabolic–fluidic hybrid therapies; modulation of astrocytic signaling programs. | [122] |

| Clinical Translation Interface | Ensures predictable solute kinetics relevant for biomarker analysis, therapeutic distribution, and disease staging. | Distorted biomarker clearance curves; uneven therapeutic dispersion; reduced diagnostic sensitivity of fluid-based measures. | Glymphatic flow indices; tracer washout kinetics; solute-distribution modeling. | Polarity-restoring molecular therapies; improved drug-routing techniques; AI-informed mechanistic modeling. | [123] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brehar, F.-M.; Costea, D.; Tataru, C.P.; Rădoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Munteanu, O.; Tulin, A. The Fluidic Connectome in Brain Disease: Integrating Aquaporin-4 Polarity with Multisystem Pathways in Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311536

Brehar F-M, Costea D, Tataru CP, Rădoi MP, Ciurea AV, Munteanu O, Tulin A. The Fluidic Connectome in Brain Disease: Integrating Aquaporin-4 Polarity with Multisystem Pathways in Neurodegeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311536

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrehar, Felix-Mircea, Daniel Costea, Calin Petru Tataru, Mugurel Petrinel Rădoi, Alexandru Vlad Ciurea, Octavian Munteanu, and Adrian Tulin. 2025. "The Fluidic Connectome in Brain Disease: Integrating Aquaporin-4 Polarity with Multisystem Pathways in Neurodegeneration" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311536

APA StyleBrehar, F.-M., Costea, D., Tataru, C. P., Rădoi, M. P., Ciurea, A. V., Munteanu, O., & Tulin, A. (2025). The Fluidic Connectome in Brain Disease: Integrating Aquaporin-4 Polarity with Multisystem Pathways in Neurodegeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311536