Prominin-1 Regulates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Homeostasis: Transcriptomic Insights into Degenerative Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

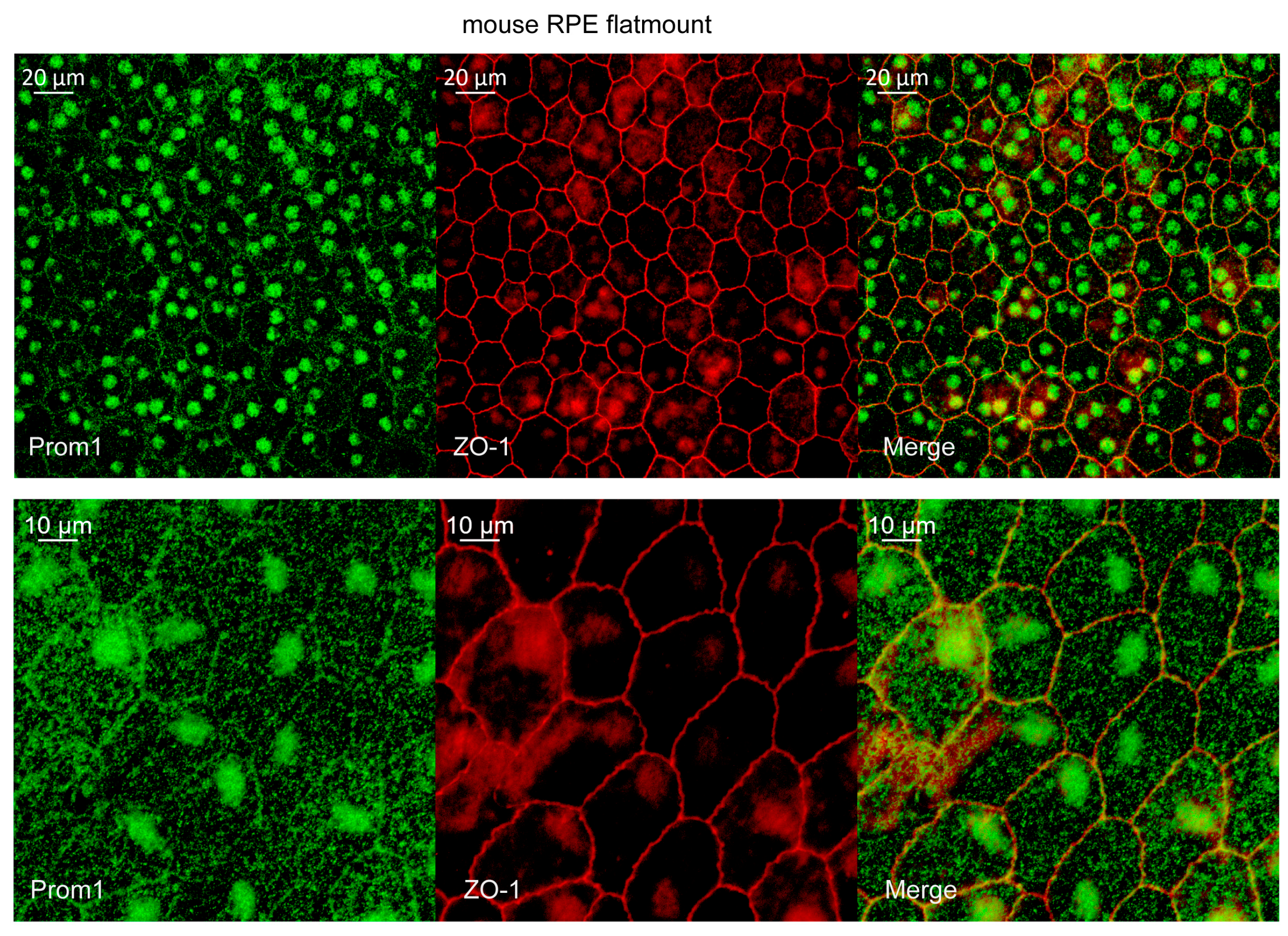

2.1. Prom1 Is Expressed in Mouse RPE In Situ

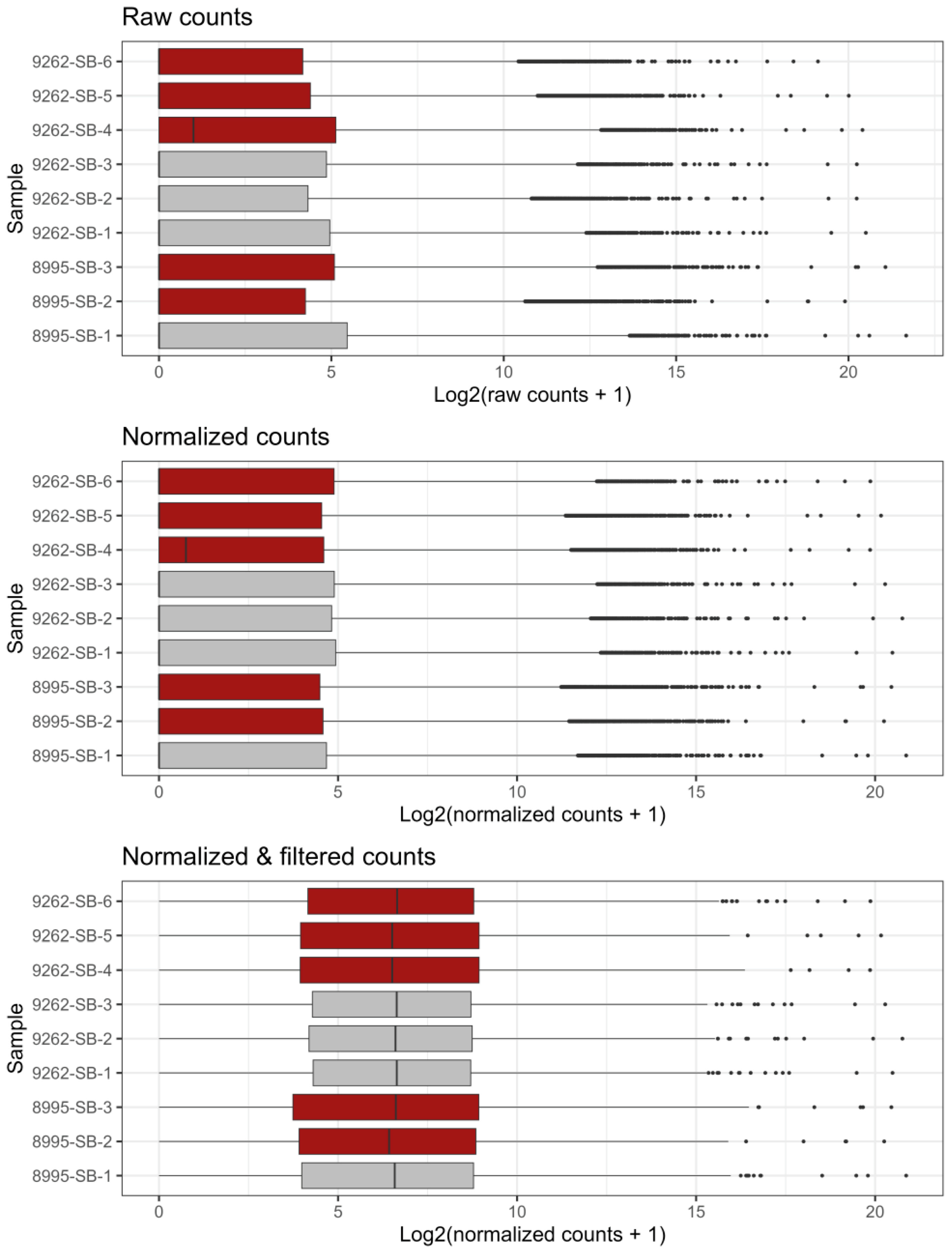

2.2. Bulk RNA Sequencing of WT and Prom1-KO mRPE Cells

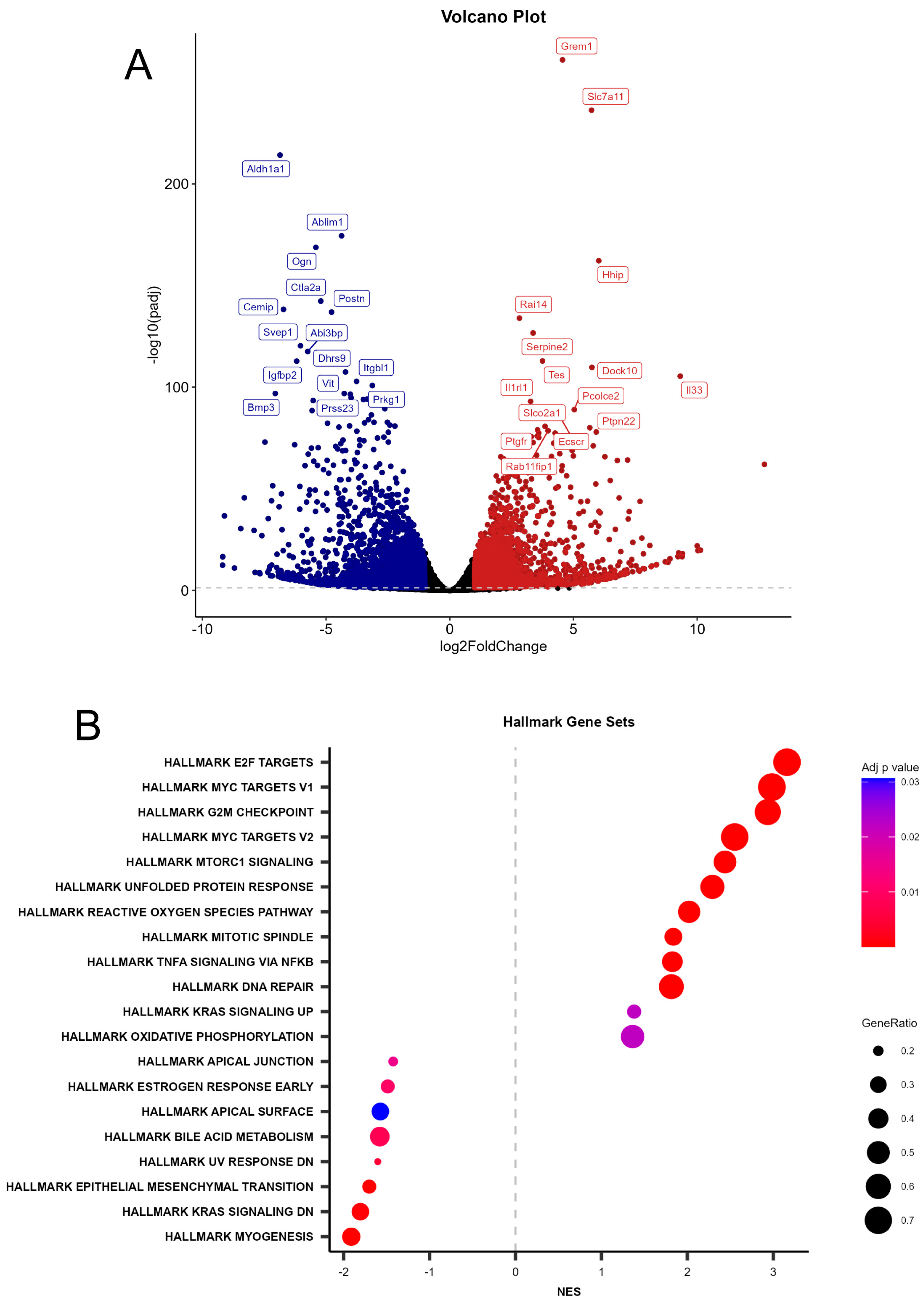

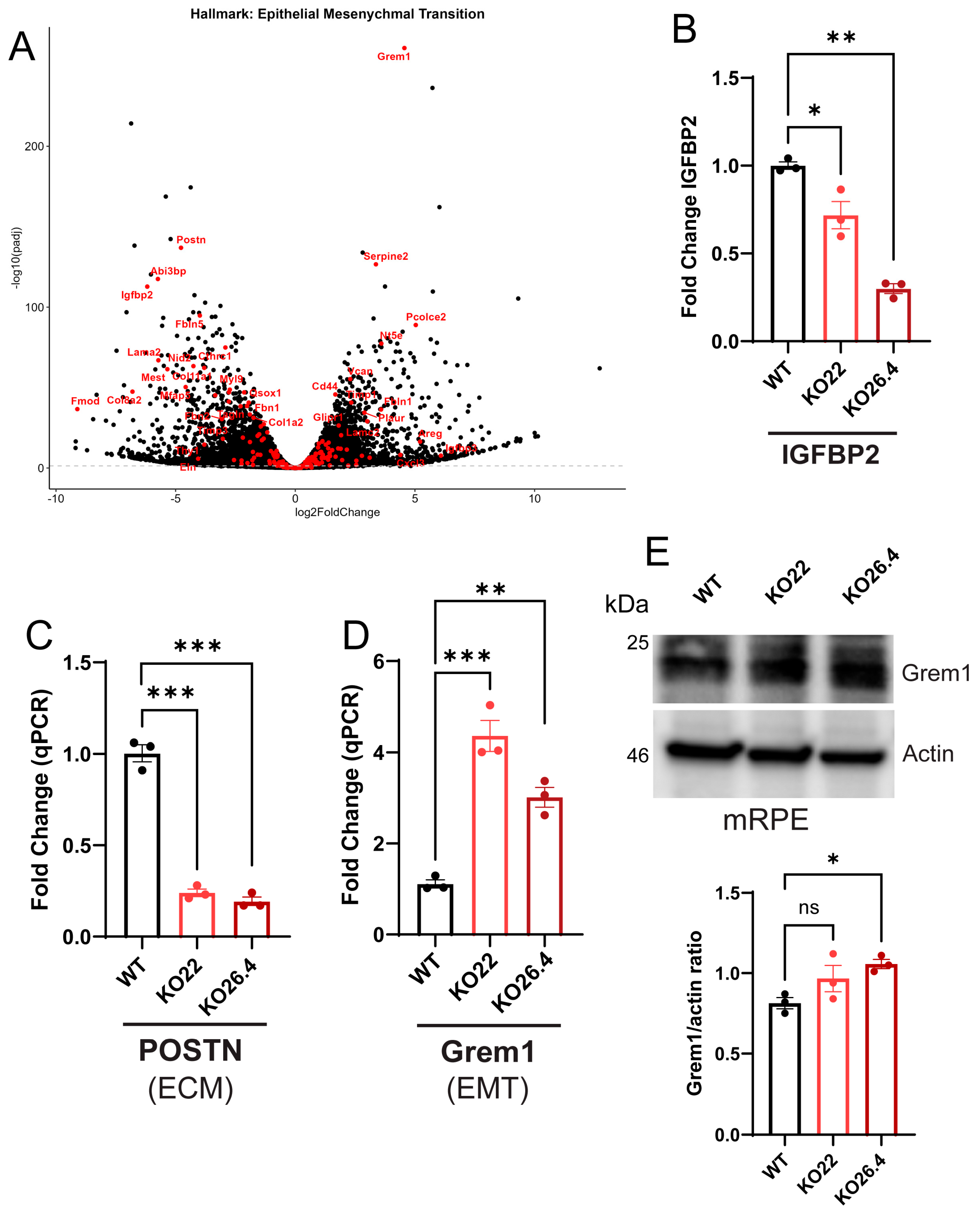

2.3. Differential Expression and Gene Set Enrichment Analyses

2.4. Heatmap Analysis and Biological Context

2.5. Gene Network Map in Prom1-KO Versus WT mRPE

2.6. Validation of Transcriptomic Data

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Mice and Colony Management

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Generation of Prom1-Deficient mRPE Cells via CRISPR/Cas9

4.5. Mouse RPE Flat Mount Preparation and Immunohistochemistry

4.6. Mouse Retina Sections and Confocal Imaging

4.7. Western Blotting

4.8. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.9. Bulk RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IRDs | Inherited Retinal Dystrophies |

| aAMD | Atrophic Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| RPE | Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| Prom1 | Prominin-1 (CD133) |

| STGD4 | Stargardt disease 4 |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| DEG | Differential Gene Expression |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| mRPE | mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Spaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| Cas9 | CRISPR-associated system 9 |

| gRNA | guide RNA |

| DAPI | 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

Appendix A

References

- Corradetti, G.; Verma, A.; Tojjar, J.; Almidani, L.; Oncel, D.; Emamverdi, M.; Bradley, A.; Lindenberg, S.; Nittala, M.G.; Sadda, S.R. Retinal Imaging Findings in Inherited Retinal Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelska, K.; Szaflik, J.P.; Guszkowska, M.; Kurowska, A.K.; Zaleska-Zmijewska, A. Characteristics of Rare Inherited Retinal Dystrophies in Adaptive Optics-A Study on 53 Eyes. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanie-Jahromi, F.; Nowroozzadeh, M.H. RPE based gene and cell therapy for inherited retinal diseases: A review. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 217, 108961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbe, L.; Sakthivel, H.; Makia, M.S.; Kakakhel, M.; Conley, S.M.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R.; Naash, M.I. Prph2 disease mutations lead to structural and functional defects in the RPE. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kang, S.W.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, S.J. Genetic and clinical characteristics of PROM1-related retinal degeneration in Korean. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Neyra, K.; Coco-Martin, R.M.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, L.A.; Gobelli, D.; Garcia-Ferrer, Y.; Palma-Vecino, R.; Telleria, J.J.; Simarro, M.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Fernandez-Bueno, I. Clinical exome analysis and targeted gene repair of the c.1354dupT variant in iPSC lines from patients with PROM1-related retinopathies exhibiting diverse phenotypes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia, S.; Godfrey, W.; Yin, A.H.; Atkins, K.; Warnke, R.; Holden, J.T.; Bray, R.A.; Waller, E.K.; Buck, D.W. A novel five-transmembrane hematopoietic stem cell antigen: Isolation, characterization, and molecular cloning. Blood 1997, 90, 5013–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigmann, A.; Corbeil, D.; Hellwig, A.; Huttner, W.B. Prominin, a novel microvilli-specific polytopic membrane protein of the apical surface of epithelial cells, is targeted to plasmalemmal protrusions of non-epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12425–12430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleskac, P.; Fargeas, C.A.; Veselska, R.; Corbeil, D.; Skoda, J. Emerging roles of prominin-1 (CD133) in the dynamics of plasma membrane architecture and cell signaling pathways in health and disease. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragi, S.D.; Lima de Carvalho, J.R., Jr.; Tanaka, A.J.; Park, K.S.; Mahajan, V.B.; Maumenee, I.H.; Tsang, S.H. Compound heterozygous novel frameshift variants in the PROM1 gene result in Leber congenital amaurosis. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2019, 5, a004481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, M.A.; Corbeil, D.; Koch, J.; Hellwig, A.; Wilson-Wheeler, J.C.; Bridges, R.J.; Kumaramanickavel, G.; John, S.; Nancarrow, D.; Roper, K.; et al. A frameshift mutation in prominin (mouse)-like 1 causes human retinal degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lillo, C.; Chien, J.; Yu, Z.; Michaelides, M.; Klein, M.; Howes, K.A.; Li, Y.; Kaminoh, Y.; et al. Mutant prominin 1 found in patients with macular degeneration disrupts photoreceptor disk morphogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2908–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Xiao, X.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Caruso, R.; MacDonald, I.; Sieving, P.; Riazuddin, S.; Hejtmancik, J.F. Severe retinitis pigmentosa mapped to 4p15 and associated with a novel mutation in the PROM1 gene. Hum. Genet. 2007, 122, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pras, E.; Abu, A.; Rotenstreich, Y.; Avni, I.; Reish, O.; Morad, Y.; Reznik-Wolf, H.; Pras, E. Cone-rod dystrophy and a frameshift mutation in the PROM1 gene. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eidinger, O.; Leibu, R.; Newman, H.; Rizel, L.; Perlman, I.; Ben-Yosef, T. An intronic deletion in the PROM1 gene leads to autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy. Mol. Vis. 2015, 21, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.O.; Bolz, H.J. Pediatric Cone-Rod Dystrophy with High Myopia and Nystagmus Suggests Recessive PROM1 Mutations. Ophthalmic Genet. 2015, 36, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, S.; Cheng, J.; Shasaltaneh, M.D.; Wei, C.; Yang, L.; Fu, S.; Zou, H.; Khan, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; et al. Genetic identification and molecular modeling characterization reveal a novel PROM1 mutation in Stargardt4-like macular dystrophy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, B.J.; Skitsko, D.; Kriese, L.M.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Ju, M.J.; Moritz, O.L. Prominin-1 null Xenopus laevis develop subretinal drusenoid-like deposits, cone-rod dystrophy, and RPE atrophy. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs262298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, R.W.; Munoz, B.; Ahmed, M.I.; Bittencourt, M.; Schonbach, E.M.; Michaelides, M.; Birch, D.; Zrenner, E.; Ervin, A.M.; Charbel Issa, P.; et al. The Progression of the Stargardt Disease Type 4 (ProgStar-4) Study: Design and Baseline Characteristics (ProgStar-4 Report No. 1). Ophthalmic Res. 2018, 60, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniazeva, M.; Chiang, M.F.; Morgan, B.; Anduze, A.L.; Zack, D.J.; Han, M.; Zhang, K. A new locus for autosomal dominant stargardt-like disease maps to chromosome 4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 64, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalem, M.F.; Omari, A.A.; Schlegel, D.; Khan, N.W.; Jayasundera, T. Macular hyperpigmentary changes in ABCA4-Stargardt disease. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Paavo, M.; Zernant, J.; Stong, N.; Laurente, Z.; Bearelly, S.; Nagasaki, T.; Tsang, S.H.; Goldstein, D.B.; Allikmets, R. Modification of the PROM1 disease phenotype by a mutation in ABCA4. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019, 40, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permanyer, J.; Navarro, R.; Friedman, J.; Pomares, E.; Castro-Navarro, J.; Marfany, G.; Swaroop, A.; Gonzalez-Duarte, R. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with early macular affectation caused by premature truncation in PROM1. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 2656–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavo, M.; Lee, W.; Parmann, R.; Lima de Carvalho, J.R., Jr.; Zernant, J.; Tsang, S.H.; Allikmets, R.; Sparrow, J.R. Insights Into PROM1-Macular Disease Using Multimodal Imaging. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricca, A.M.; Han, I.C.; Hoffmann, J.; Stone, E.M.; Sohn, E.H. Macular Atrophy and Phenotypic Variability in Autosomal Dominant Stargardt-Like Macular Dystrophy Due to Prom1 Mutation. Retina 2023, 43, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Yin, J.; Winborn, C.S.; Zhang, Q.; Yue, J.; Chaum, E. Prominin-1 Is a Novel Regulator of Autophagy in the Human Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 2366–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Yang, T.S.; Nabit, B.P.; Krystofiak, E.S.; Rex, T.S.; Chaum, E. Prominin-1 Knockdown Causes RPE Degeneration in a Mouse Model. Cells 2024, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Yin, J.; Huo, W.; Chaum, E. Loss of Prom1 impairs autophagy and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2023, 238, 2373–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yuan, D.; Shen, H.; Mao, X.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Q. Gremlin-1: An endogenous BMP antagonist induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and interferes with redifferentiation in fetal RPE cells with repeated wounds. Mol. Vis. 2019, 25, 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Winokur, P.N.; Subramanian, P.; Bullock, J.L.; Arocas, V.; Becerra, S.P. Comparison of two neurotrophic serpins reveals a small fragment with cell survival activity. Mol. Vis. 2017, 23, 372–384. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; He, D.; Liao, C.; Lin, S.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.L.; Hu, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; et al. IL-1/IL-1R signaling induced by all-trans-retinal contributes to complement alternative pathway activation in retinal pigment epithelium. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 3660–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Katschke, K.J., Jr.; Li, Y.; Truong, T.; Lee, W.P.; Diehl, L.; Rangell, L.; Tao, J.; Arceo, R.; Eastham-Anderson, J.; et al. IL-33 amplifies an innate immune response in the degenerating retina. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutty, R.K.; Samuel, W.; Chen, S.; Vijayasarathy, C.; Dun, Y.; Mysona, B.; Wiggert, B.; Smith, S.B. Immunofluorescence analysis of the expression of Norpeg (Rai14) in retinal Muller and ganglion cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 404, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J. Retinoic Acid-Induced Protein 14 (RAI14) Promotes mTOR-Mediated Inflammation Under Inflammatory Stress and Chemical Hypoxia in a U87 Glioblastoma Cell Line. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 39, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, T.; Frank, D.; Kuwahara, K.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Pipes, G.C.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Richardson, J.A.; Katus, H.A.; Olson, E.N.; Frey, N. Two novel members of the ABLIM protein family, ABLIM-2 and -3, associate with STARS and directly bind F-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8393–8403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Czajkowsky, D.M.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, X. abLIM1 constructs non-erythroid cortical actin networks to prevent mechanical tension-induced blebbing. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chaum, E. A reassessment of insulin-like growth factor binding protein gene expression in the human retinal pigment epithelium. J. Cell Biochem. 2003, 89, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; King, J.L.; Guidry, C. Phenotype-associated changes in retinal pigment epithelial cell expression of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 5449–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.W.Y.; Connor, T.B.; Kassem, I.S.; Costakos, D.M.; Chaurasia, S.S. Small Leucine-Rich Proteoglycans (SLRPs) in the Retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercau, M.E.; Akalu, Y.T.; Mazzoni, F.; Gyimesi, G.; Alberto, E.J.; Kong, Y.; Hafler, B.P.; Finnemann, S.C.; Rothlin, C.V.; Ghosh, S. Inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium drives early-onset photoreceptor degeneration in Mertk-associated retinitis pigmentosa. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louer, E.M.M.; Gunzel, D.; Rosenthal, R.; Carmone, C.; Yi, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; den Hollander, A.I.; Deen, P.M.T. Differential day-night expression of tight junction components in murine retinal pigment epithelium. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 193, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlecht, A.; Leimbeck, S.V.; Jagle, H.; Feuchtinger, A.; Tamm, E.R.; Braunger, B.M. Deletion of Endothelial Transforming Growth Factor-beta Signaling Leads to Choroidal Neovascularization. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 2570–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Yamada, K.; Suzumura, A.; Kataoka, K.; Takayama, K.; Sugimoto, M.; Terasaki, H.; Kaneko, H. Caveolin-1 Promotes Cellular Senescence in Exchange for Blocking Subretinal Fibrosis in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, A.; Saegusa, K.; Noguchi, T.; Sadamitsu, C.; Nishitoh, H.; Nagai, S.; Koyasu, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. ROS-dependent activation of the TRAF6-ASK1-p38 pathway is selectively required for TLR4-mediated innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, S. Complement C5a promotes human retinal pigment epithelial cell viability and migration through SLC38A1-mediated glutamine metabolism. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 214, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tzekov, R.; Su, M.; Zhu, Y.; Han, A.; Li, W. Hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage and protective role of peroxiredoxin 6 protein via EGFR/ERK signaling pathway in RPE cells. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1169211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Su, M.Y.; Chen, T.T.; Hong, H.Y.; Han, A.D.; Li, W.S. Oxidative stress affects retinal pigment epithelial cell survival through epidermal growth factor receptor/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 10, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Topalovski, M.; Toombs, J.E.; Wright, C.M.; Moore, Z.R.; Boothman, D.A.; Yanagisawa, H.; Wang, H.; Witkiewicz, A.; Castrillon, D.H.; et al. Fibulin-5 Blocks Microenvironmental ROS in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 5058–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosze, B.; Suarez-Navarro, J.; Soofi, A.; Lauderdale, J.D.; Dressler, G.R.; Brown, N.L. Multiple roles for Pax2 in the embryonic mouse eye. Dev. Biol. 2021, 472, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.M.; Fan, B.; Li, Y.L.; Zuo, Z.Y.; Li, G.Y. Oxidative Stress-Involved Mitophagy of Retinal Pigment Epithelium and Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 3265–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Siegel, D. Functions of NQO1 in Cellular Protection and CoQ(10) Metabolism and its Potential Role as a Redox Sensitive Molecular Switch. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Ichijo, H.; Naguro, I. Molecular functions of ASK family in diseases caused by stress-induced inflammation and apoptosis. J. Biochem. 2021, 169, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Barron, E.; He, S.; Ryan, S.J.; Hinton, D.R. Regulation of RPE intercellular junction integrity and function by hepatocyte growth factor. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.R.; Zhu, Y.S.; Yuan, W.T.; Pan, X.Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.D. Hepatocyte growth factor promotes retinal pigment epithelium cell activity through MET/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 17, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, G.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Yang, S.; Bo, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wan, X.; Zhu, X.; et al. AIM2 activation mediated by RIPK1/3-dependent mitochondrial DNA release drives Abeta(1-40)-Induced retinal pigment epithelium injury. Cell Commun. Signal 2025, 23, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wert, K.J.; Velez, G.; Cross, M.R.; Wagner, B.A.; Teoh-Fitzgerald, M.L.; Buettner, G.R.; McAnany, J.J.; Olivier, A.; Tsang, S.H.; Harper, M.M.; et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3) regulates oxidative stress at the vitreoretinal interface. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 124, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, K.; Wang, L.; Chou, C.H.; Liu, K.; Nakata, T.; Jaiswal, A.; Yao, J.; Lefkovith, A.; Omar, A.; Perrigoue, J.G.; et al. QRICH1 dictates the outcome of ER stress through transcriptional control of proteostasis. Science 2021, 371, eabb6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira, B.; Vandenbempt, V.; Bauza-Martinez, J.; Crutzen, R.; Negueruela, J.; Ibrahim, H.; Winder, M.L.; Brahma, M.K.; Vekeriotaite, B.; Martens, P.J.; et al. PTPN2 Regulates the Interferon Signaling and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response in Pancreatic beta-Cells in Autoimmune Diabetes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edilova, M.I.; Abdul-Sater, A.A.; Watts, T.H. TRAF1 Signaling in Human Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strick, D.J.; Vollrath, D. Focus on molecules: MERTK. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 91, 786–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; Tsai, S.H.; Yeh, S.I.; Sun, M.H.; Tsao, Y.P. A PEDF-Derived Short Peptide Prevents Sodium Iodate-Induced Retinal Degeneration in Rats by Activating the SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 Pathway in the RPE Cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, S.; Onishi, A.; Misaki, K.; Yonemura, S.; Sugita, S.; Ito, H.; Ohigashi, Y.; Ema, M.; Sakaguchi, H.; Nishida, K.; et al. Neural retina-specific Aldh1a1 controls dorsal choroidal vascular development via Sox9 expression in retinal pigment epithelial cells. eLife 2018, 7, e32358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, A.P.; Mulfaul, K.; Mullin, N.K.; Flamme-Wiese, M.J.; Giacalone, J.C.; Stone, E.M.; Tucker, B.A.; Scheetz, T.E.; Mullins, R.F. Single-cell transcriptomics of the human retinal pigment epithelium and choroid in health and macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24100–24107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhirachaikulpanich, D.; Li, X.; Porter, L.F.; Paraoan, L. Integrated Microarray and RNAseq Transcriptomic Analysis of Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Choroid in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbanova, J.; Lorico, A.; Bornhauser, M.; Corbeil, D.; Fargeas, C.A. Prominin-1/CD133: Lipid Raft Association, Detergent Resistance, and Immunodetection. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Scheiter, A.; Song, D.; Feng, G.S. Identification of CD133+ intercellsomes in intercellular communication to offset intracellular signal deficit. eLife 2023, 12, RP86824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunukova, A.; Neradil, J.; Skoda, J.; Jaros, J.; Hampl, A.; Sterba, J.; Veselska, R. Atypical nuclear localization of CD133 plasma membrane glycoprotein in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, O.; Bammidi, S.; Gautam, P.; Babu, V.S.; Liu, H.; Shang, P.; Xin, Y.; Mahally, E.; Nemani, M.; Koontz, V.; et al. Activated mTOR Signaling in the RPE Drives EMT, Autophagy, and Metabolic Disruption, Resulting in AMD-Like Pathology in Mice. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Cano, M.; Satyanarayana, G.; Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Itoh, K.; Sharma, A.; Bhutto, I.; et al. Mitophagy initiates retrograde mitochondrial-nuclear signaling to guide retinal pigment cell heterogeneity. Autophagy 2023, 19, 966–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, M.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wan, X.; Jiang, M.; et al. SLC7A11 Reduces Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization by Inhibiting RPE Ferroptosis and VEGF Production. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 639851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perino, A.; Demagny, H.; Velazquez-Villegas, L.; Schoonjans, K. Molecular Physiology of Bile Acid Signaling in Health, Disease, and Aging. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 683–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, P.; Cariou, B.; Lien, F.; Kuipers, F.; Staels, B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 147–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.; Rudd Zhong Manis, J.; Ronczkowski, N.M.; Bui, T.; Oxenrider, A.; Jadeja, R.N.; Thounaojam, M.C. Unveiling the gut-eye axis: How microbial metabolites influence ocular health and disease. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1377186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubieta, D.; Warden, C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Brantley, M.A., Jr. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid Confers Protection Against Oxidative Stress via Autophagy Induction in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, A.; Delgado, A.; Jadeja, R.N.; Martin, P.M.; Bartoli, M.; Thounaojam, M.C. Pharmacological and Metabolic Significance of Bile Acids in Retinal Diseases. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daruich, A.; Jaworski, T.; Henry, H.; Zola, M.; Youale, J.; Parenti, L.; Naud, M.C.; Delaunay, K.; Bertrand, M.; Berdugo, M.; et al. Oral Ursodeoxycholic Acid Crosses the Blood Retinal Barrier in Patients with Retinal Detachment and Protects Against Retinal Degeneration in an Ex Vivo Model. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murase, H.; Tsuruma, K.; Shimazawa, M.; Hara, H. TUDCA Promotes Phagocytosis by Retinal Pigment Epithelium via MerTK Activation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Barrios, A.; Alvarez, L.; Saenz de Santa Maria, P.; Garcia, M.; Alvarez-Buylla, J.R.; Pereiro, R.; Gonzalez-Iglesias, H. Dysregulated lipid metabolism in a retinal pigment epithelial cell model and serum of patients with age-related macular degeneration. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.D.; Mondon, I.; Ellis, C.; Muir, A.M.; Turner, S.; Keeling, E.; Wai, H.A.; Chatelet, D.S.; Johnson, D.A.; Tumbarello, D.A.; et al. Whole RNA-Seq Analysis Reveals Longitudinal Proteostasis Network Responses to Photoreceptor Outer Segment Trafficking and Degradation in RPE Cells. Cells 2025, 14, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Geathers, J.S.; Grillo, S.L.; Weber, S.R.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Sundstrom, J.M. Role of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Retinal Pigment Epithelium Dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.Y.; Butcher, E.; Saint-Geniez, M. EMT and EndMT: Emerging Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chtcheglova, L.A.; Ohlmann, A.; Boytsov, D.; Hinterdorfer, P.; Priglinger, S.G.; Priglinger, C.S. Nanoscopic Approach to Study the Early Stages of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) of Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells In Vitro. Life 2020, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Fu, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: Implications for Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Progression. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Godino, R.; Garland, D.L.; Pierce, E.A. Isolation, culture and characterization of primary mouse RPE cells. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatright, J.H.; Dalal, N.; Chrenek, M.A.; Gardner, C.; Ziesel, A.; Jiang, Y.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Nickerson, J.M. Methodologies for analysis of patterning in the mouse RPE sheet. Mol. Vis. 2015, 21, 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Chaum, E.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, L.R. Age-related susceptibility to apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelial cells is triggered by disruption of p53-Mdm2 association. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 8350–8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene (Mouse) | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-actin | CCTGGATAGCAACGTAGATGC | ACCTTCTACAATGACCTGGC |

| Prom1 | AACATATGCGCGGGAGAG | CAGTTTCTGGGTCCCTTTGA |

| Pink1 | CTGATCGAGGAGAAGCAGGC | GCCAATGGCTTGCCCTATGA |

| Ogn | CGCAGCTGGACTCACATGTT | TCTTTCTTGGTTGGTAATGATGCT |

| Mertk | TGGATACGTGCATCTGTCCG | GAGGAGCAGAGAATGGGCTG |

| Grem1 | CTTCGCAGACCTGGAGACG | CAGGTTGTGGTGGGGACTG |

| Slc7a11 | CAGGCATCTTCATCTCCCCC | GAGCAGTTCCACCCAGACTC |

| Ablim1 | GAGGCCATCGGTCTGCTTC | GAAATGCTTGGTCTGCACCC |

| Igfbp2 | CACAGGTGACACTGCAGACG | GAACACAGCCAGCTCCTTCA |

| Aldh1a1 | TGAGCCTGTCACCTGTGTTC | CCTTCTTCCACGTGGCAGAT |

| Postn | ATGACAAGGTCCTGGCTCAC | CCCGCAGATAGCACCTTGAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huo, W.; Yin, J.; Ghose, P.; Schafer, J.C.; Chaum, E.; Bhattacharya, S. Prominin-1 Regulates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Homeostasis: Transcriptomic Insights into Degenerative Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311539

Huo W, Yin J, Ghose P, Schafer JC, Chaum E, Bhattacharya S. Prominin-1 Regulates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Homeostasis: Transcriptomic Insights into Degenerative Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311539

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Weihong, Jinggang Yin, Purnima Ghose, Jenny C. Schafer, Edward Chaum, and Sujoy Bhattacharya. 2025. "Prominin-1 Regulates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Homeostasis: Transcriptomic Insights into Degenerative Mechanisms" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311539

APA StyleHuo, W., Yin, J., Ghose, P., Schafer, J. C., Chaum, E., & Bhattacharya, S. (2025). Prominin-1 Regulates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Homeostasis: Transcriptomic Insights into Degenerative Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311539