The Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Structure and Crystallization Behavior of Nanocomposites Based on Paraffin and Polyethylene

Abstract

1. Introduction

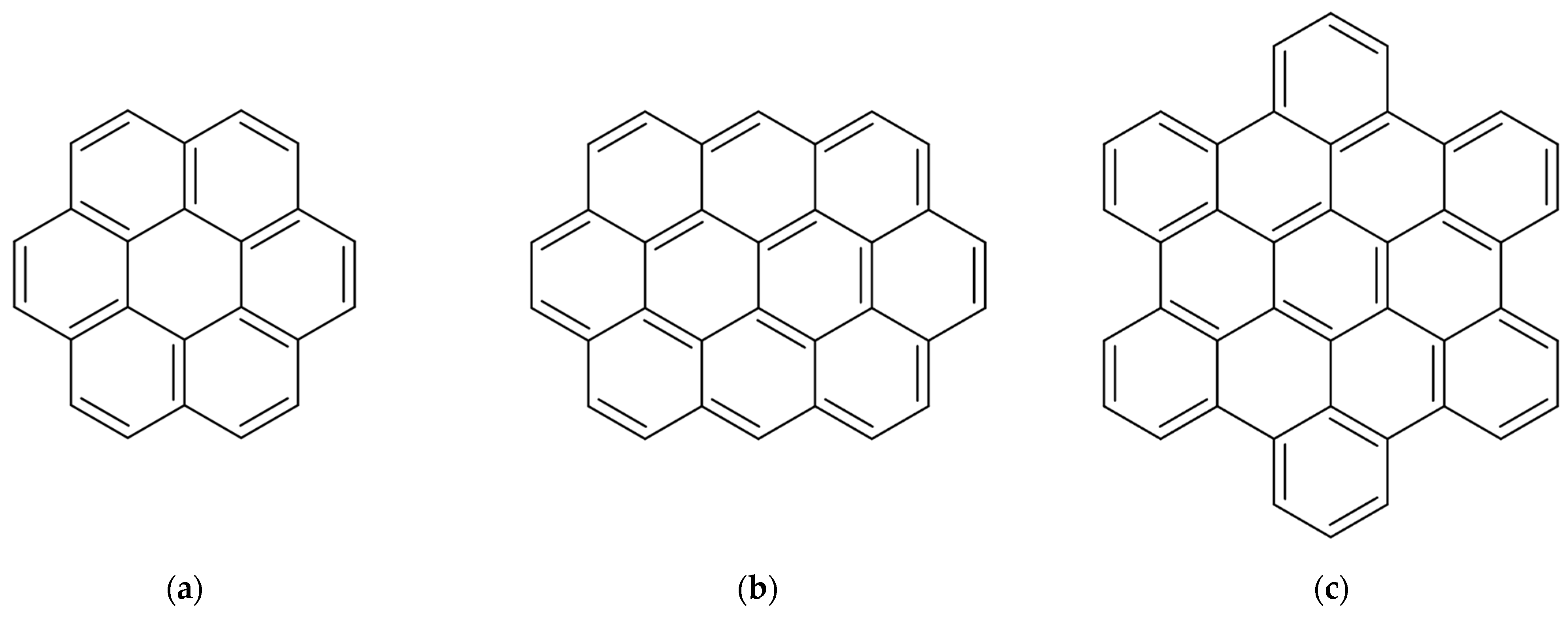

2. Model and Simulation Technique

3. Results and Discussion

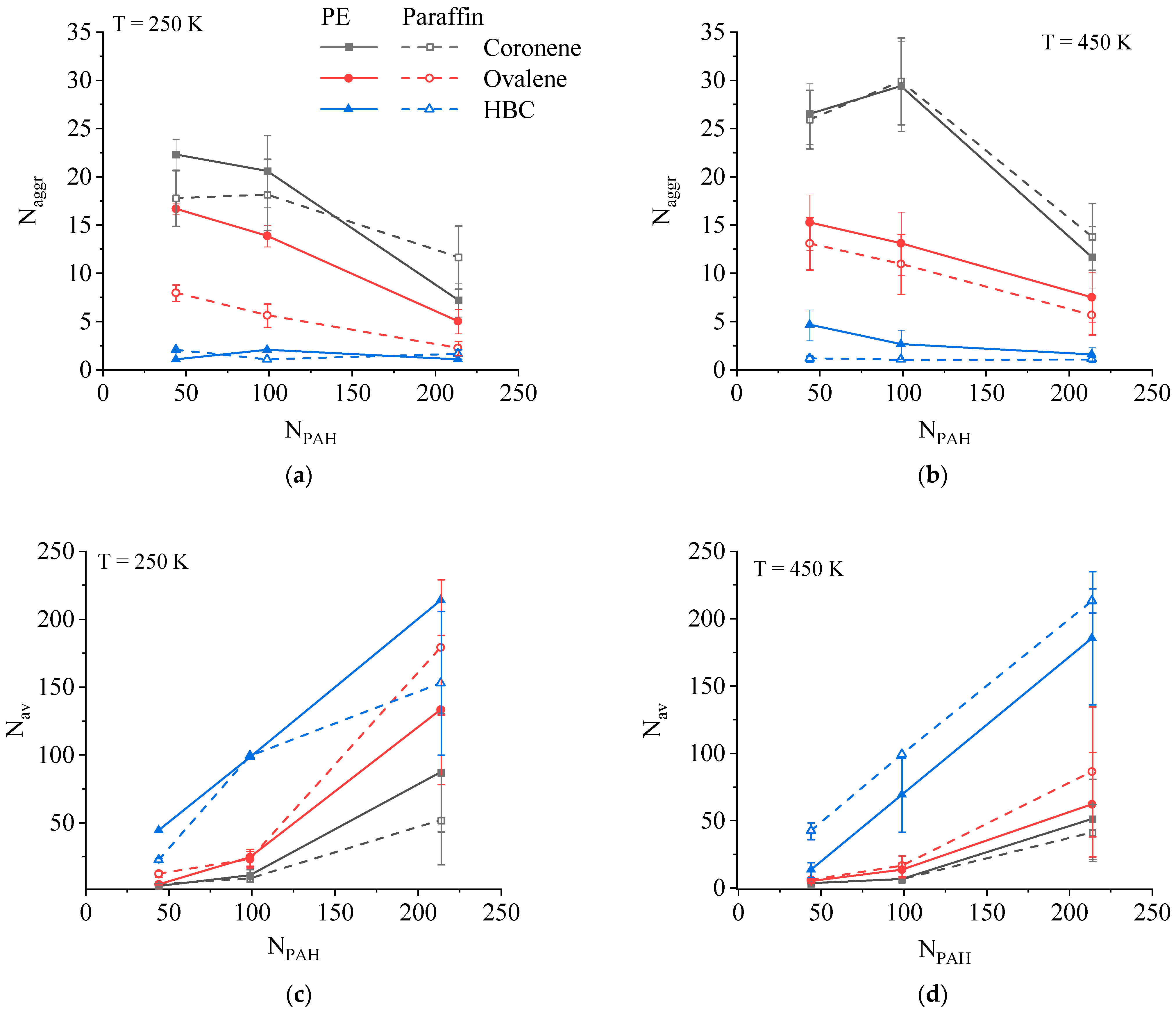

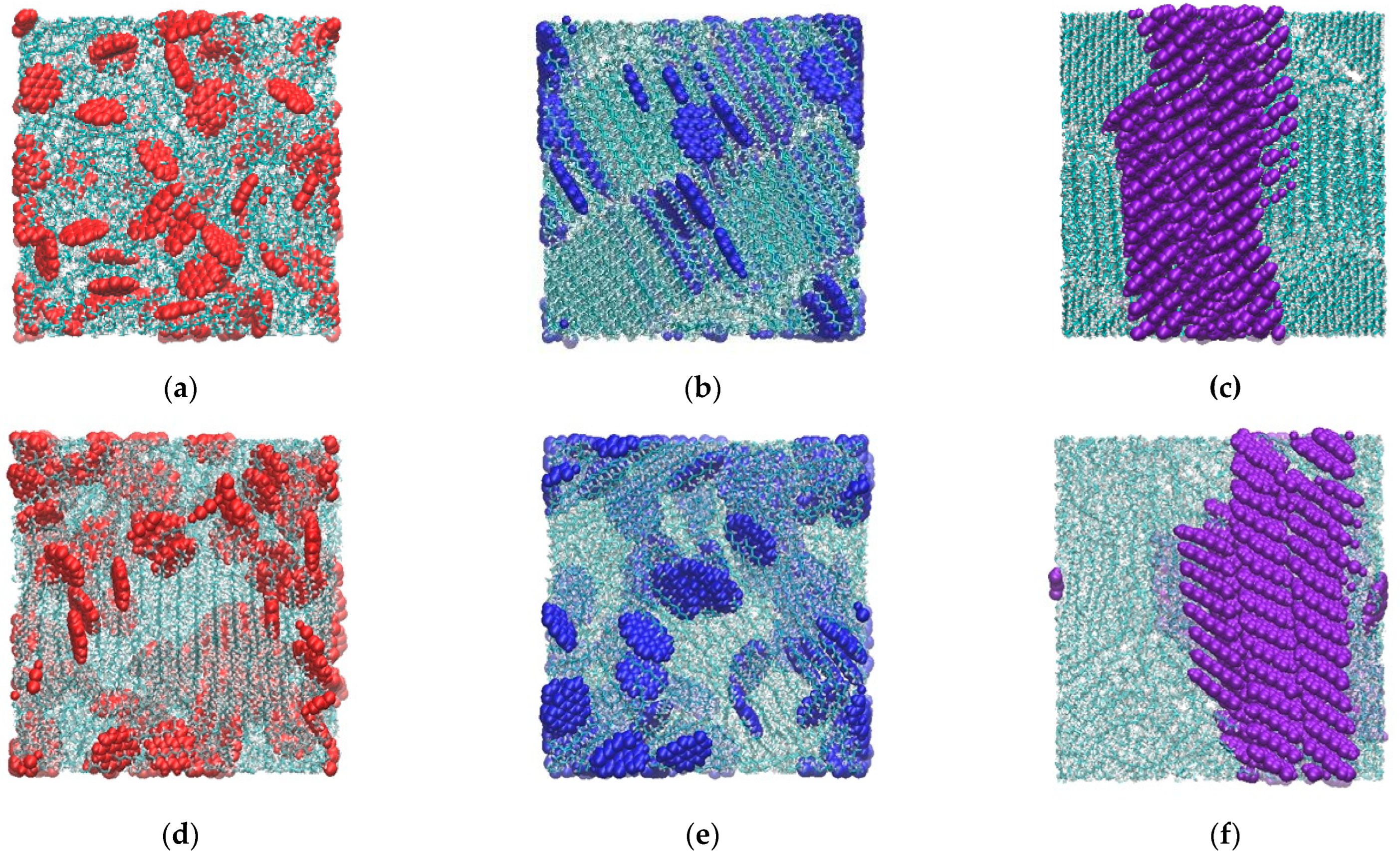

3.1. Aggregation Behavior of PAH in PE and Paraffin

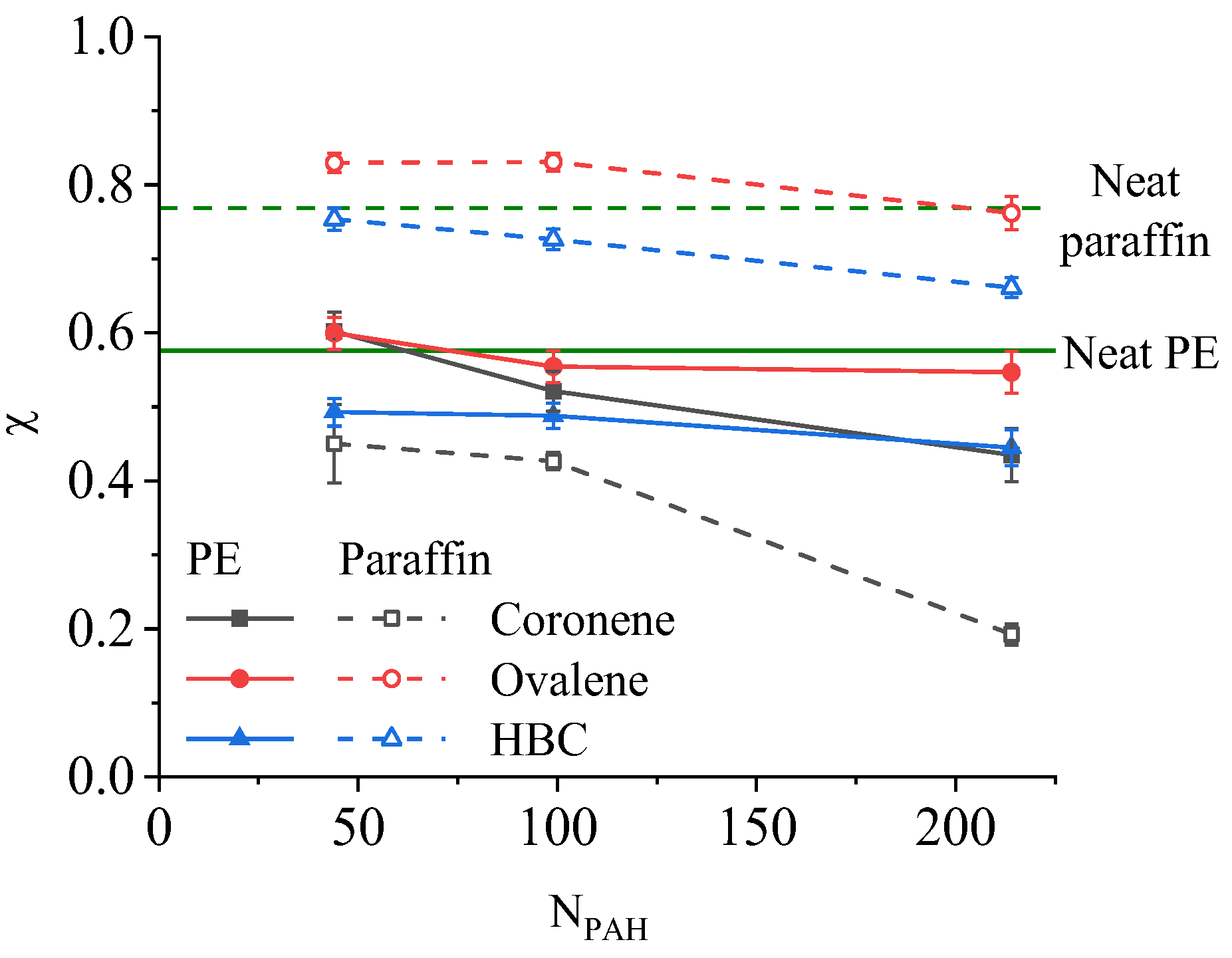

3.2. Crystallinity of the Composite Matrix

3.3. Influence of PAH on the Phase Transition of Composites

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manu, K.M.; Soni, S.; Murthy, V.R.K.; Sebastian, M.T. Ba(Zn1/3Ta2/3)O3 Ceramics Reinforced High Density Polyethylene for Microwave Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013, 24, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.K.; Tripathi, M. Thermal Properties of Silicon Powder Filled High-Density Polyethylene Composites. Thermochim. Acta 2010, 502, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yanilmaz, M.; Toprakci, O.; Fu, K.; Zhang, X. A Review of Recent Developments in Membrane Separators for Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3857–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mahdavi, H. Recent Development of Polyolefin-Based Microporous Separators for Li−Ion Batteries: A Review. Chem. Rec. 2020, 20, 570–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiker, D.M.D.; Usha, Z.R.; Wan, C.; Hassaan, M.M.E.; Chen, X.; Li, L. Recent Progress of Composite Polyethylene Separators for Lithium/Sodium Batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 564, 232853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P.; Chen, R.; Thring, R.H. Polyethylene-Carbon Material for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Bipolar Plates. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2008, 222, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, C.; Zhang, B.; Dominguez-Ramos, A.; Ibañez, R.; Irabien, A.; Chen, Y. Enhancing Fouling Resistance of Polyethylene Anion Exchange Membranes Using Carbon Nanotubes and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Desalination 2017, 411, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, A. Form-Stable Paraffin/High Density Polyethylene Composites as Solid–Liquid Phase Change Material for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation and Thermal Properties. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 2033–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrazeq, H.; Sobolčiak, P.; Al-Ali Al-Maadeed, M.; Ouederni, M.; Krupa, I. Recycled Polyethylene/Paraffin Wax/Expanded Graphite Based Heat Absorbers for Thermal Energy Storage: An Artificial Aging Study. Molecules 2019, 24, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkri, M.; Lachheb, M.; Nógellová, Z.; Boh, B.; Sumiga, B.; AlMaadeed, M.A.; Fethi, A.; Krupa, I. Thermal Properties of Phase-Change Materials Based on High-Density Polyethylene Filled with Micro-Encapsulated Paraffin Wax for Thermal Energy Storage. Energy Build. 2015, 88, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. Preparation of Polyethylene–Paraffin Compound as a Form-Stable Solid-Liquid Phase Change Material. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2000, 64, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rashid, A.; Akram, S.; Rehan, Z.A.; Razzaq, W. A Comprehensive Review on Polymeric Nano-Composite Membranes for Water Treatment. J. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 1000179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Bonyadi, S.; Chung, T.-S. Exploring the Potential of Commercial Polyethylene Membranes for Desalination by Membrane Distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 497, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Li, R.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; You, X.; Fan, S.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Submicron Freestanding Ultrahigh-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Membranes: Application in Membrane Distillation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 14399–14406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Leng, Y.; Gao, P. Processing of Hydroxyapatite Reinforced Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3471–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, P.N.; AlMaadeed, M.A.A. Processing and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites. Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci. 2015, 1, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, R.K.; Barghouty, A.F.; Dahche, H.M. Space Radiation Transport Properties of Polyethylene-Based Composites. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1027, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Kausar, A.; Muhammad, B.; Gul, S.; Farooq, M. A Review on Polymeric Nanocomposites of Nanodiamond, Carbon Nanotube, and Nanobifiller: Structure, Preparation and Properties. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2015, 54, 1379–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.C.; Chowdhury, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Hossain, M.K. Applications, Drawbacks, and Future Scope of Nanoparticle-Based Polymer Composites. In Nanoparticle-Based Polymer Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 243–275. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkiewicz, S.; Pypeć, K.; Irska, I.; Piesowicz, E. Functional Polymer Hybrid Nanocomposites Based on Polyolefins: A Review. Processes 2020, 8, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.N.; Rao, G.S.S.; Mathur, A.B.; Jasra, R. Polyolefin/Graphene Nanocomposites: A Review. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 23615–23632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, O.C. The Asphaltenes. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2011, 4, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, K.; Hammami, A.; Kharrat, A.; Zhang, D.; Allenson, S.; Creek, J.; Kabir, S.; Jamaluddin, A.; Marshall, A.G.; Rodgers, R.P.; et al. Asphaltenes—Problematic but Rich in Potential. Oilfield Rev. 2007, 19, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kamkar, M.; Natale, G. A Review on Novel Applications of Asphaltenes: A Valuable Waste. Fuel 2021, 285, 119272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tangpong, X.W. Review: Tribological Behavior of Polyethylene-Based Nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, K.; Tavman, İ.H.; Seki, Y.; Turgut, A.; Omastova, M.; Ozdemir, I. Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Expanded Graphite/High Density Polyethylene Nanocomposites. Compos. B Eng. 2013, 53, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fim, F.d.C.; Basso, N.R.S.; Graebin, A.P.; Azambuja, D.S.; Galland, G.B. Thermal, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties of Polyethylene–Graphene Nanocomposites Obtained by in Situ Polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 128, 2630–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.; Elleithy, R.; Al-Zahrani, S.M.; Ali, M.A. Characterization and Processing of High Density Polyethylene/Carbon Nano-Composites. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Akchurin, A.; Liu, T.; Wood, W.; Tangpong, X.; Akhatov, I.S.; Zhong, W.-H. Mechanical Properties, Tribological Behavior, and Biocompatibility of High-Density Polyethylene/Carbon Nanofibers Nanocomposites. J. Compos. Mater. 2015, 49, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, S.; Varanda, F.R.; Zhil’tsova, T.V.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Simões, J.A.O. Mechanical Properties of High Density Polyethylene/Carbon Nanotube Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3071–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lv, F.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, L. Structure Evolution of Polyethylene-Plasticizer Film at Industrially Relevant Conditions Studied by in-Situ X-Ray Scattering: The Role of Crystal Stress. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 101, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkova, E.A. Surface Modification of Articles Made from Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2004, 31, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, T.P.; Luyt, A.S.; Pérez-Camargo, R.A.; Müller, A.J. The Influence of Paraffin Wax Addition on the Isothermal Crystallization of LLDPE. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, T.P.; Luyt, A.S.; Pérez-Camargo, R.A.; Iturrospe, A.; Arbe, A.; Zubitur, M.; Mugica, A.; Müller, A.J. Plasticization and Cocrystallization in LLDPE/Wax Blends. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2016, 54, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, I.; Miková, G.; Luyt, A.S. Phase Change Materials Based on Low-Density Polyethylene/Paraffin Wax Blends. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 4695–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Z.A.; Ali, H.M.; Khushnood, S. Recent Advances on Thermal Conductivity Enhancement of Phase Change Materials for Energy Storage System: A Review. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2018, 127, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Fuchs, A.; Wirtz, R.A. Polymeric Phase Change Composites for Thermal Energy Storage. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 93, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielichowska, K.; Pielichowski, K. Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 65, 67–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggenmueller, R.; Fischer, J.E.; Winey, K.I. Single Wall Carbon Nanotube/Polyethylene Nanocomposites: Nucleating and Templating Polyethylene Crystallites. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 2964–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Xia, R.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y. Carbon Nanotubes Induced Nonisothermal Crystallization of Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene with Reduced Chain Entanglements. Mater. Lett. 2012, 89, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuibaid, A.Z.A.; Iqbal, M.Z. Thermally Reduced Graphene/Polyethylene Nanocomposites: Effects of Graphene on Isothermal and Nonisothermal Crystallization of Polyethylene. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E.; Papageorgiou, D.G.; Valles, C.; Wurm, A.; Terzopoulou, Z.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Schick, C.; Chrissafis, K.; Vourlias, G. Insights into Crystallization and Melting of High Density Polyethylene/Graphene Nanocomposites Studied by Fast Scanning Calorimetry. Polym. Test. 2018, 67, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E.; Wurm, A.; Schick, C.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Chrissafis, K.; Vourlias, G. Effect of Graphene Nanoplatelets Diameter on Non-Isothermal Crystallization Kinetics and Melting Behavior of High Density Polyethylene Nanocomposites. Thermochim. Acta 2016, 643, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E.; Arvanitidis, I.; Christofilos, D.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Chrissafis, K.; Vourlias, G. Calculation of the Degree of Crystallinity of HDPE/GNPs Nanocomposites by Using Various Experimental Techniques: A Comparative Study. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piorkowska, E. Crystallization in Polymer Composites and Nanocomposites. In Handbook of Polymer Crystallization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Minkova, L.; Magagnini, P.L. Crystallization Behaviour and Thermal Stability of HDPE Filled during Polymerization. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1993, 42, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Michailidis, N.; Mountakis, N.; Argyros, A.; Spiridaki, M.; Moutsopoulou, A.; Papadakis, V.; Charitidis, C. High-Density Polyethylene/Carbon Black Composites in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Conductivity, Thermal, Rheological, and Mechanical Responses. Polymers 2023, 15, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Su, Y.; Gao, X.; Qian, Q.; Chen, X.; Wittenbrink, R.; Wang, D. Confined Crystallization Behaviors in Polyethylene/Silica Nanocomposites: Synergetic Effects of Interfacial Interactions and Filler Network. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2017, 55, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Diallo, M.S.; Saha, S.K.; Abass, O.A.; Sharma, A.; Balasubramanian, G. Effect of Temperature and Graphite Particle Fillers on Thermal Conductivity and Viscosity of Phase Change Material N-Eicosane. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2017, 114, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, V.v.; Gorbacheva, S.N.; Kostyuk, A.v.; Antonov, S.v.; Borisova, Y.Y.; Borisov, D.N.; Yakubov, M.R. Composites Based on Neat and Modified Asphaltenes and Paraffin: Structure, Rheology and Heat Conductivity. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, L.; Zou, B.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, T.; Cong, L.; Jiang, F.; Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Ding, Y. Expanded Graphite—Paraffin Composite Phase Change Materials: Effect of Particle Size on the Composite Structure and Properties. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 171, 115015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Hioki, K.; Kono, K.; Hiejima, Y.; Nitta, K. Effects of Liquid Paraffin on Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Linear High-Density Polyethylene. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 8459–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoabisane, M.F.T.; Luyt, A.S.; van Sittert, C.G.C.E. Comparative Experimental and Modelling Study of the Thermal and Thermo-Mechanical Properties of LLDPE/Wax Blends. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyulin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Larin, S.V.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Lyulin, A.V. Microsecond Atomic-Scale Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Polyimides. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 6357–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Roy, S.; Karimi-Varzaneh, H.A. Validation of Force Fields of Rubber through Glass-Transition Temperature Calculation by Microsecond Atomic-Scale Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarychev, V.M.; Larin, S.V.; Lukasheva, N.V.; Glova, A.D.; Lyulin, S.V. Evaluation of the Characteristic Equilibration Times of Bulk Polyimides via Full-Atomic Computer Simulation. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2013, 55, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larin, S.V.; Falkovich, S.G.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Lyulin, A.V.; Lyulin, S.V. Molecular-Dynamics Simulation of Polyimide Matrix Pre-Crystallization near the Surface of a Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkovich, S.G.; Larin, S.V.; Lyulin, A.V.; Yudin, V.E.; Kenny, J.M.; Lyulin, S. V Influence of the Carbon Nanofiller Surface Curvature on the Initiation of Crystallization in Thermoplastic Polymers. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48606–48612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarychev, V.; Larin, S.; Lyulin, A.; Dingemans, T.; Kenny, J.; Lyulin, S. Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Initial Crystallization Stage in an SWCNT-Polyetherimide Nanocomposite. Polymers 2017, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarychev, V.M.; Larin, S.V.; Kenny, J.M.; Lyulin, S.V. The Initial Stage of Thermoplastic Polyimide Crystallization: Computer Simulations and Experiments. Rev. Adv. Chem. 2021, 11, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerze, H.; Mittal, J.; McHugh, A.J. Ab Initio Crystallization of Alkanes: Structure and Kinetics of Nuclei Formation. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 9151–9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, D.A.; Rutledge, G.C. Molecular Simulation of Flow-Enhanced Nucleation in n -Eicosane Melts under Steady Shear and Uniaxial Extension. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 244903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T. Computer Modeling of Polymer Crystallization—Toward Computer-Assisted Materials’ Design. Polymer 2009, 50, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T. Molecular Dynamics Modeling of the Crystal-Melt Interfaces and the Growth of Chain Folded Lamellae. In Interphases and Mesophases in Polymer Crystallization III; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 37–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T. Molecular Dynamics in Fiber Formation of Polyethylene and Large Deformation of the Fiber. Polymer 2013, 54, 3086–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Turci, F.; Schilling, T. Crystallization Mechanism in Melts of Short N-Alkane Chains. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 214904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Berryman, J.T.; Schilling, T. Crystal Nucleation Mechanism in Melts of Short Polymer Chains under Quiescent Conditions and under Shear Flow. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.; Vega, J.F.; Martínez-Salazar, J. Molecular Dynamics Simulations for the Description of Experimental Molecular Conformation, Melt Dynamics, and Phase Transitions in Polyethylene. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 5016–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoabisane, M.F.T.; van Sittert, C.G.C.E.; Luyt, A.S. An Atomistic Molecular Dynamic Model to Study the Properties of LLDPE and Wax. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, W.S.; Li, Z.S. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Polyethylene on Single Wall Carbon Nanotube. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 094902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Liao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xia, W.; Gao, W. Crystallization and Melting of Polymer Chains on Graphene and Graphene Oxide. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 12235–12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Xia, D.; Xue, Q.; Yan, K.; Gao, X.; Li, Q. Computational Analysis of Effect of Modification on the Interfacial Characteristics of a Carbon Nanotube–Polyethylene Composite System. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 3534–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Feng, T.; Wang, H.; Li, W. Molecular Insight into the Microstructure and Hydrogen Barrier Properties of Graphene Reinforced Polyethylene Composites. Mater. Lett. 2025, 401, 139225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, H.; Ghasemi, H.; Wallace, C.; Hatami, K. Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanotube-filled Polyethylene Composites: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, E1850–E1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yuan, C.; Bai, X. Tribological Behaviors of Composites Reinforced by Different Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Using Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Wear 2021, 476, 203669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glova, A.D.; Volgin, I.V.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Larin, S.V.; Lyulin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A. Toward Realistic Computer Modeling of Paraffin-Based Composite Materials: Critical Assessment of Atomic-Scale Models of Paraffins. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 38834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarychev, V.M.; Glova, A.D.; Larin, S.V.; Lyulin, A.V.; Lyulin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A. Cooling-Rate Computer Simulations for the Description of Crystallization of Organic Phase-Change Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glova, A.D.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Larin, S.V.; Lyulin, A.V.; Lyulin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A. Asphaltenes as Novel Thermal Conductivity Enhancers for Liquid Paraffin: Insight from in Silico Modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 117112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glova, A.D.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Larin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Lyulin, S.V. Size Matters: Asphaltenes with Enlarged Aromatic Cores Promote Heat Transfer in Organic Phase-Change Materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 32196–32207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, R.; Müllen, K. Forever Young: Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons as Model Cases for Structural and Optical Studies. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2010, 23, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Torres, S.W.; Messman, J.; Bowen, D.E.; Bowler, N. Dynamics of Model Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Compound-Epoxy Composites: A Dielectric Study. Polymer 2018, 136, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, Flexible, and Free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Páll, S.; Zhmurov, A.; Bauer, P.; Abraham, M.; Lundborg, M.; Gray, A.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Heterogeneous Parallelization and Acceleration of Molecular Dynamics Simulations in GROMACS. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 134110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B.; Brooks, B.R.; MacKerell, A.D.; Venable, R.M.; Pastor, R.W. An Ab Initio Study on the Torsional Surface of Alkanes and Its Effect on Molecular Simulations of Alkanes and a DPPC Bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 5300–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B.; Venable, R.M.; Freites, J.A.; O’Connor, J.W.; Tobias, D.J.; Mondragon-Ramirez, C.; Vorobyov, I.; MacKerell, A.D.; Pastor, R.W. Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 7830–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J.Y.; Son, N.; Shin, J.; Chava, R.K.; Joo, S.W.; Kang, M. N-Eicosane-Fe3O4@SiO2@Cu Microcapsule Phase Change Material and Its Improved Thermal Conductivity and Heat Transfer Performance. Mater. Des. 2021, 198, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlosinger, A.P.; Bentilla, E.W. Research and Development Study on Thermal Control by Use of Fusible Materials; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1965.

- Headen, T.F.; Boek, E.S.; Jackson, G.; Totton, T.S.; Müller, E.A. Simulation of Asphaltene Aggregation through Molecular Dynamics: Insights and Limitations. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 1108–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glova, A.D.; Larin, S.V.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Kenny, J.M.; Lyulin, A.V.; Lyulin, S.V. Toward Predictive Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Asphaltenes in Toluene and Heptane. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 20005–20014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmares, M.; Blanco, M.; Goddard, W.A.; Ross, R.B.; Caldwell, G.; Chou, S.-H.; Pham, J.; Olofson, P.M.; Thomas, C. Hildebrand and Hansen Solubility Parameters from Molecular Dynamics with Applications to Electronic Nose Polymer Sensors. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyulin, S.V.; Larin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Nazarychev, V.M.; Falkovich, S.G.; Yudin, V.E.; Svetlichnyi, V.M.; Gofman, I.V.; Lyulin, A.V. Thermal Properties of Bulk Polyimides: Insights from Computer Modeling versus Experiment. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composite | Npar | NPE | NPAH | ωPAH, % | Natoms | dbox, nm (T = 450 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraffin + coronene | 500 | - | 44 | 8.6 | 32,584 | 7.25 |

| 99 | 17.3 | 34,564 | 7.44 | |||

| 214 | 31.2 | 38,704 | 7.57 | |||

| Paraffin + ovalene | 500 | - | 44 | 11.0 | 33,024 | 7.20 |

| 99 | 21.8 | 35,554 | 7.42 | |||

| 214 | 37.7 | 40,844 | 7.78 | |||

| Paraffin + HBC | 500 | - | 44 | 14.0 | 33,640 | 7.21 |

| 99 | 26.8 | 36,940 | 7.49 | |||

| 214 | 44.2 | 43,840 | 7.91 | |||

| PE + coronene | - | 20 | 44 | 8.6 | 31,624 | 6.91 |

| 99 | 17.5 | 33,604 | 7.07 | |||

| 214 | 31.4 | 37,744 | 7.38 | |||

| PE + ovalene | - | 20 | 44 | 11.1 | 32,064 | 6.94 |

| 99 | 21.9 | 34,594 | 7.13 | |||

| 214 | 37.8 | 39,884 | 7.98 | |||

| PE + HBC | - | 20 | 44 | 14.0 | 32,680 | 6.97 |

| 99 | 27.0 | 35,980 | 7.18 | |||

| 214 | 44.3 | 42,880 | 7.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larin, S.V.; Melnikova, S.D.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Lyulin, S.V. The Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Structure and Crystallization Behavior of Nanocomposites Based on Paraffin and Polyethylene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311509

Larin SV, Melnikova SD, Gurtovenko AA, Lyulin SV. The Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Structure and Crystallization Behavior of Nanocomposites Based on Paraffin and Polyethylene. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311509

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarin, Sergey V., Sofia D. Melnikova, Andrey A. Gurtovenko, and Sergey V. Lyulin. 2025. "The Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Structure and Crystallization Behavior of Nanocomposites Based on Paraffin and Polyethylene" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311509

APA StyleLarin, S. V., Melnikova, S. D., Gurtovenko, A. A., & Lyulin, S. V. (2025). The Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Structure and Crystallization Behavior of Nanocomposites Based on Paraffin and Polyethylene. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311509