Chemical Transformations of Lignin Under the Action of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ionic Liquids: Covalent Bonding and the Role of Anion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Weight Characteristics of IL-Treated Lignin

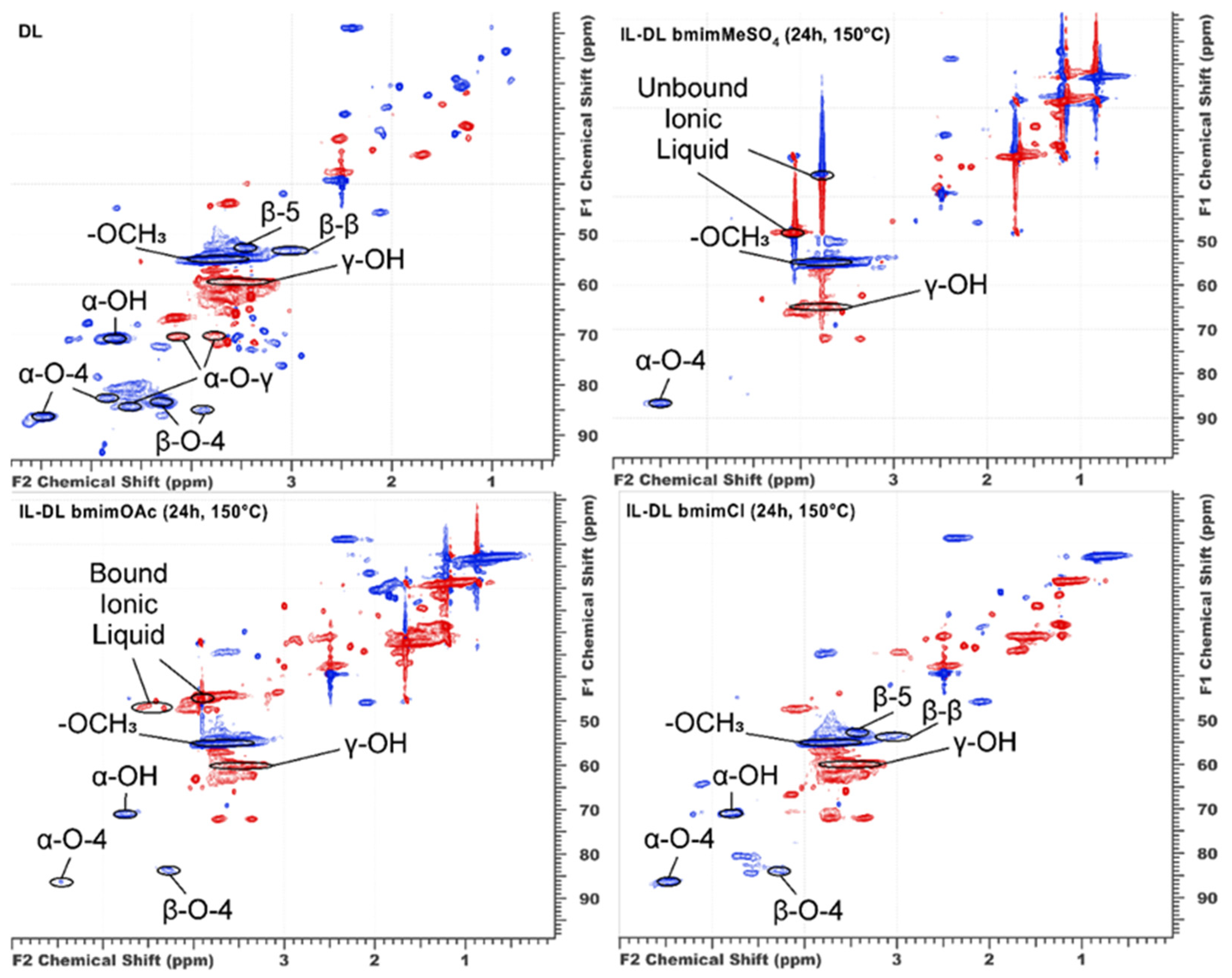

2.2. Changes in Functional and Elemental Composition

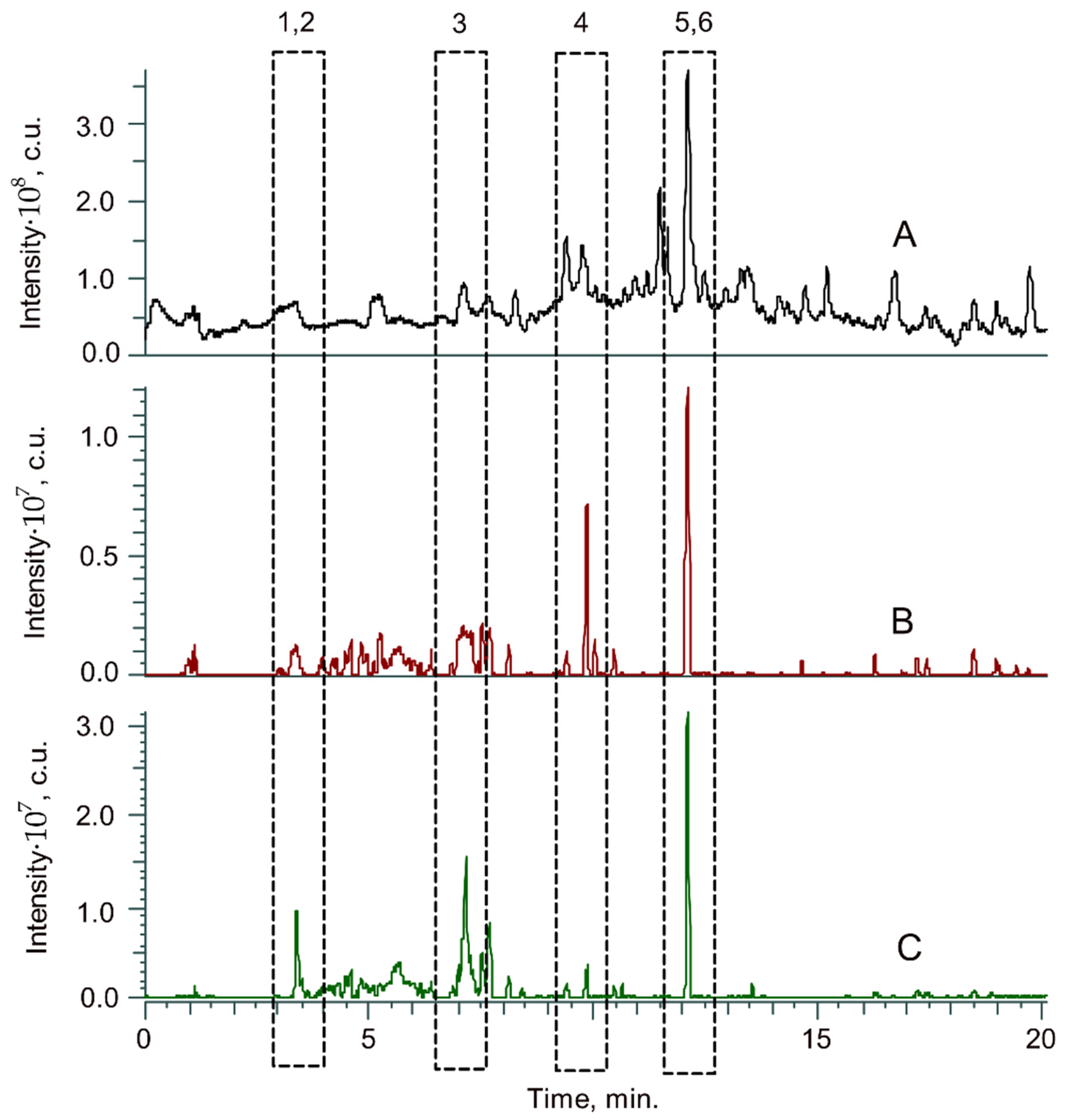

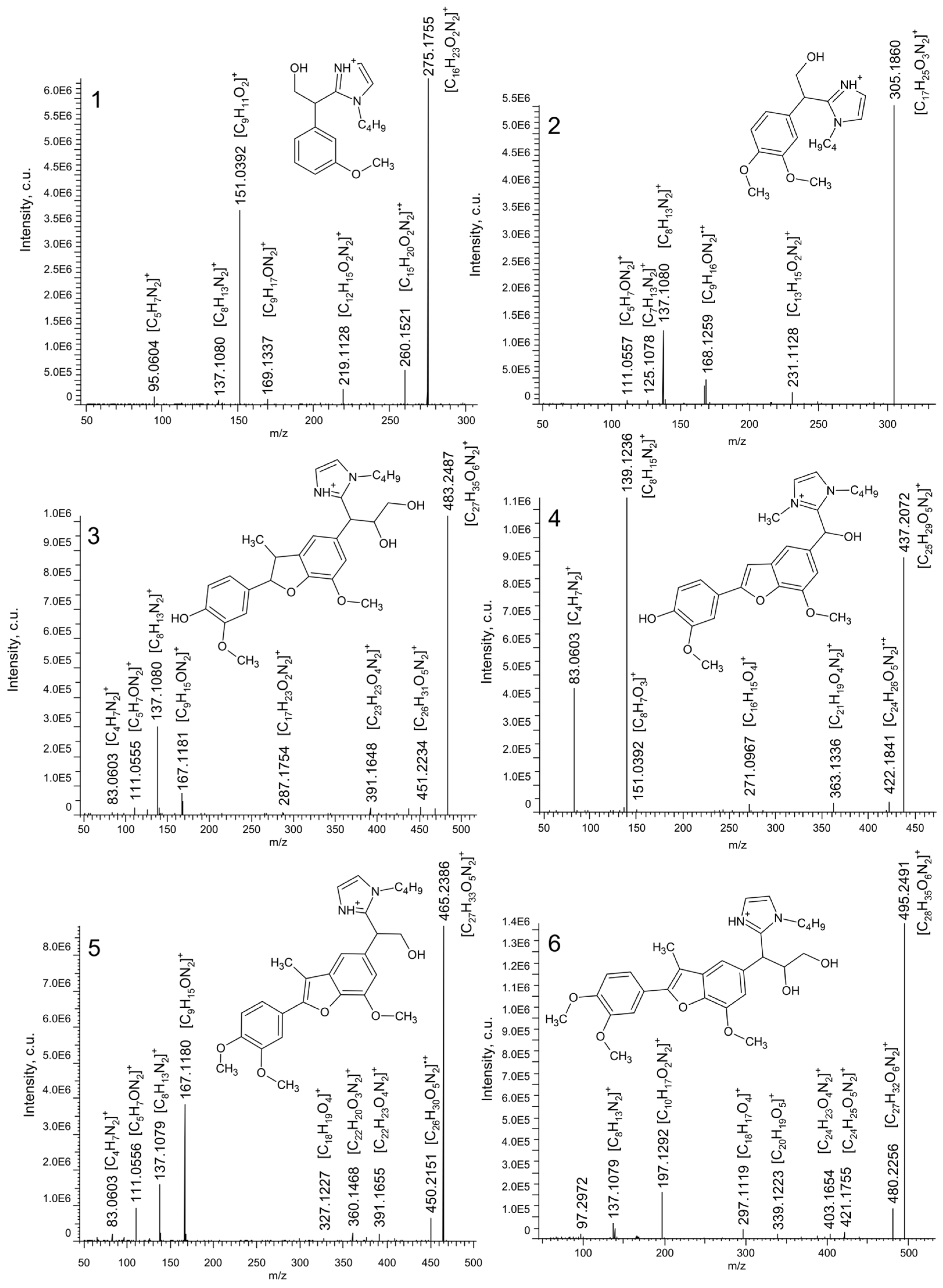

2.3. Molecular-Level Identification of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

3. Discussion

3.1. IL Anion-Governed Dichotomy of Lignin Transformation Pathways

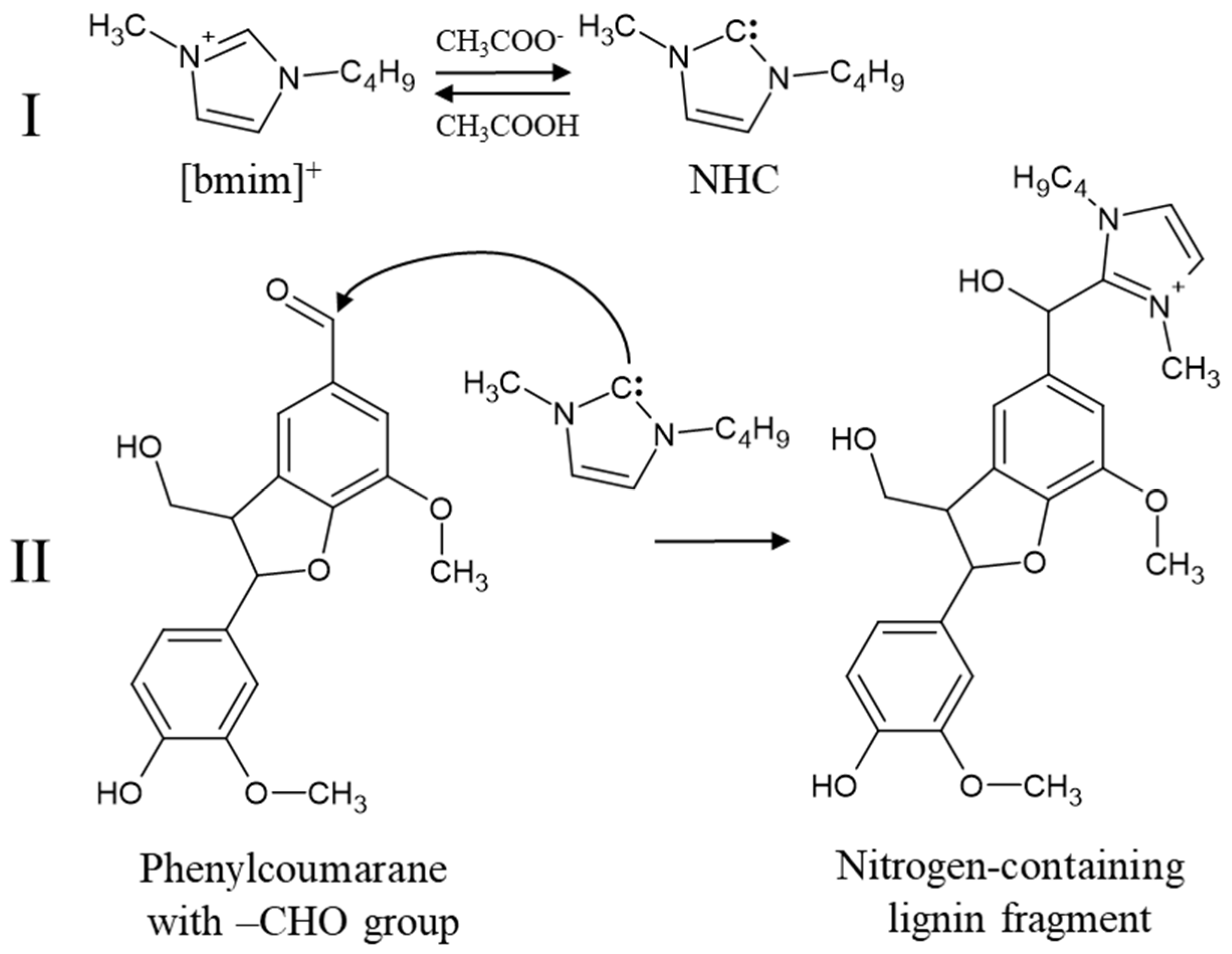

3.2. Mechanism of Covalent Cation Bonding: The Role of N-Heterocyclic Carbene

3.3. Competing Processes in the [bmim]MeSO4 System: Condensation vs. Functionalization

3.4. Implications for Biorefining and Future Perspectives

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Lignin Isolation and Treatment Procedures

4.3. Analytical Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bmim | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium |

| DL | Dioxane lignin |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HRMS | High-resolution mass spectrometry |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear single quantum coherence |

| IL | Ionic liquid |

| MWD | Molecular weight distribution |

| NHC | N-heterocyclic carbene |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| RDB | Ring and double bond equivalent |

| TIC | Total ion current |

| XIC | Extracted ion current |

References

- Calvo-Flores, F.G. Lignin: A Renewable Raw Material. In Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials; Hashmi, S., Choudhury, I.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, A.; Mulla, S.I.; Pant, D.; Sharma, T.; Kumar, A. Lignin as Potent Industrial Biopolymer: An Introduction. In Lignin; Sharma, S., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer Series on Polymer and Composite Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliszek, M.; Podkościelna, B. The application of lignin as renewable raw material in chemical industry. Ann. UMCS Chem. 2019, 73, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevallos Torres, L.A.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Tanobe, V.O.A.; Karp, S.G.; Guimarães Lorenci, L.C.; Faulds, C.; Soccol, C.R. Lignin as a potential source of high-added value compounds: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, P.; Ragauskas, A.J. Fundamentals of Biomass Pretreatment by Fractionation. In Aqueous Pretreatment of Plant Biomass for Biological and Chemical Conversion to Fuels and Chemicals; Stevens, C.V., Wyman, C.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.E.; Gomes, F.J.B.; Brito, E.O.; Lelis, R.C.C.; Azevedo, A.M. A review on lignin sources and uses. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 7, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, T.; King, A.W.T.; Argyropoulos, D.S. Fractionation of Lignocellulosic Materials with Ionic Liquids. In Production of Biofuels and Chemicals with Ionic Liquids; Fang, Z., Smith, R., Jr., Qi, X., Eds.; Biofuels and Biorefineries; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Lopes, A.M.; João, K.G.; Morais, A.R.C.; Bogel-Łukasik, E.; Bogel-Łukasik, R. Ionic liquids as a tool for lignocellulosic biomass fractionation. Sustain. Chem. Process. 2013, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, K.C.; Bhanage, B.M. Factors governing dissolution process of lignocellulosic biomass in ionic liquid: Current status, overview and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocreto, J.B.; Chen, W.-H.; Rollon, A.P.; Ong, H.C.; Pétrissans, A.; Pétrissans, M.; De Luna, M.D.G. Ionic liquid dissolution utilized for biomass conversion into biofuels, value-added chemicals and advanced materials: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 445, 136733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Singh, S.; Cheng, G. Transforming lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels enabled by ionic liquid pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thöming, J.; Siedlecka, E.M.; Czerwicka, M.; Stepnowski, P.; Neumann, J. Ionic Liquids: Methods of Degradation and Recovery. In Ionic Liquids—Theory, Properties, New Approaches; Kokorin, A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Eishah, S.I. Ionic Liquids Recycling for Reuse. In Ionic Liquids—Classes and Properties; Handy, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Y.S.; Tjong, T.C.; Chew, J.W.; Hu, X. Techniques for recovery and recycling of ionic liquids: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Kumar, A.; Bhaskar, T. Ionic liquids for separation of lignin and transformation into value-added chemicals. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 34, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Tran, K.; Morgan, T.J.; Benke, P.I.; Berrueco, C.; Lorente, E.; Wu, B.C.; Keasling, J.D.; Simmons, B.A.; Holmes, B.M. The effect of ionic liquid cation and anion combinations on the macromolecular structure of lignins. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.E.S.; Harper, J.B.; Aldous, L. The effect of changing the components of an ionic liquid upon the solubility of lignin. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przypis, M.; Wawoczny, A.; Gillner, D. Biomass and Cellulose Dissolution—The Important Issue in Renewable Materials Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdía Barbará, P.; Choudhary, H.; Nakasu, P.S.; Al-Ghatta, A.; Han, Y.; Hopson, C.; Aravena, R.I.; Mishra, D.K.; Ovejero-Pérez, A.; Simmons, B.A.; et al. Recent Advances in the Use of Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents for Lignocellulosic Biorefineries and Biobased Chemical and Material Production. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 5461–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.R.; Kumar, N.; Mishra, D.K.; Simmons, B.A.; Choudhary, H.; Sale, K.L. Computational Advances in Ionic Liquid Applications for Green Chemistry: A Critical Review of Lignin Processing and Machine Learning Approaches. Molecules 2024, 29, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-L.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Sun, S.-L.; Xu, F.; Sun, R.-C. Understanding the chemical transformations of lignin during ionic liquid pretreatment. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Hou, Y. Behavior of oxygen-containing groups in grass lignin during dissolution in basic ionic liquids. Cellulose 2019, 26, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wellard, M.; Bartley, J.; O’Hara, I.; Doherty, W. Characterisation of lignins isolated from sugarcane bagasse pretreated with acidified ethylene glycol and ionic liquids. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 70, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-L.; Sun, S.-L.; Xue, B.-L.; Sun, R.-C. Quantitative structures and thermal properties of birch lignins after ionic liquid pretreatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. Ionic liquids and lignin interaction: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, T.; Nascimento, V.; Costa, A.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A.; Rabelo, S. Structural characterization of sugarcane lignins extracted from different protic ionic liquid pretreatments. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarotto, I.; Feroci, M.; Inesi, A. First direct evidence of N-heterocyclic carbene in BMIm acetate ionic liquids. An electrochemical and chemical study on the role of temperature. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 7840–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belesov, A.V.; Shkaeva, N.V.; Popov, M.S.; Skrebets, T.E.; Faleva, A.V.; Ul’yanovskii, N.V.; Kosyakov, D.S. New Insights into the Thermal Stability of 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belesov, A.V.; Mazur, D.M.; Faleva, A.V.; Varsegov, I.S.; Pikovskoi, I.I.; Ulyanovskii, N.V.; Kosyakov, D.S. 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid in Biomass Fractionation—Green Solvent or Active Reagent Toward Lignin Compounds? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achinivu, E.C. Protic Ionic Liquids for Lignin Extraction—A Lignin Characterization Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry, M.; Majira, A.; Pégot, B.; Cezard, L.; Bourdreux, F.; Clément, G.; Perreau, F.; Boutet-Mercey, S.; Diter, P.; Vo-Thanh, G.; et al. Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids as Efficient Reagents for the C−O Bond Cleavage of Lignin. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belesov, A.V.; Anikeenko, E.A.; Faleva, A.V.; Ul’yanovskii, N.V.; Kosyakov, D.S. Study of Nitrogen-Containing Products of the Interaction of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Cation with Lignin by MALDI Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 77, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belesov, A.V.; Ladesov, A.V.; Pikovskoi, I.I.; Faleva, A.V.; Kosyakov, D.S. Characterization of Ionic Liquid Lignins Isolated from Spruce Wood with 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Acetate and Methyl Sulfate and Their Binary Mixtures with DMSO. Molecules 2020, 25, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamraju, A.; Rajan, K.; Zuo, X.; Long, B.K.; Pingali, S.V.; Elder, T.J.; Labbé, N. Atomic Level Interactions and Suprastructural Configuration of Plant Cell Wall Polymers in Dialkylimidazolium Ionic Liquids. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2164–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, H.; Dong, K.; Fan, M.; Zhang, S. A DFT study on lignin dissolution in imidazolium-based ionic liquids. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 12670–12681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushammala, H.; Mao, J. A Review on the Partial and Complete Dissolution and Fractionation of Wood and Lignocelluloses Using Imidazolium Ionic Liquids. Polymers 2020, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Fu, Y.; Lu, X.; O’Hara, I.M.; Doherty, W.O.S.; Zhang, Y. Cellulose dissolution in ionic liquid from hydrogen bonding perspective: First-principles calculations. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4181–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppeler, N.; Pires, P.A.R.; Freitas, J.L.S.; El Seoud, O.A. Cellulose dissolution in mixtures of ionic liquids and molecular solvents: The fruitful synergism of experiment and theory. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 386, 122490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyakov, D.S.; Pikovskoi, I.I.; Ul’yanovskii, N.V. Dopant-assisted atmospheric pressure photoionization Orbitrap mass spectrometry—An approach to molecular characterization of lignin oligomers. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1179, 338836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Yarger, J.L.; Angell, C.A. On the Use of a Protic Ionic Liquid with a Novel Cation To Study Anion Basicity. Chemistry 2016, 22, 13312–13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, J.; Baylis, P.; Adler, E. The isolation and properties of lignins obtained by the acidolysis of spruce and aspen woods in dioxane-water medium. Can. J. Chem. 2011, 37, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, A.; Argyropoulos, D.S. 2-Chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaphospholane, a Reagent for the Accurate Determination of the Uncondensed and Condensed Phenolic Moieties in Lignins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IL | T, °C | Mn, kDa | Mw, kDa | PDI 1 (Mw/Mn) | Content of the fraction, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 kDa | 1–20 kDa | >20 kDa | |||||

| [bmim]OAc | 80 | 1.5 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 7 | 88 | 5 |

| 100 | 1.4 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 7 | 88 | 5 | |

| 120 | 1.2 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 10 | 88 | 2 | |

| 150 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 13 | 86 | 1 | |

| [bmim]Cl | 80 | 2.2 | 10.9 | 5.0 | 4 | 85 | 11 |

| 100 | 2.3 | 11.1 | 4.8 | 5 | 84 | 11 | |

| 120 | 2.7 | 10.4 | 3.9 | 4 | 86 | 10 | |

| 150 | 2.5 | 7.8 | 3.1 | 4 | 88 | 8 | |

| [bmim]MeSO4 | 80 | 2.0 | 9.4 | 4.9 | 5 | 88 | 7 |

| 100 | 2.2 | 9.0 | 4.5 | 4 | 90 | 6 | |

| 120 | 2.7 | 11.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 88 | 8 | |

| 150 | 3.4 | 15.2 | 4.4 | 2 | 84 | 14 | |

| IL | T, °C | Content, % (w/w) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -OHtotal | -OHphen | -OHaliph | -COOH | ||

| DL | - | 9.1 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 |

| [bmim]OAc | 80 | 9.9 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 0.4 |

| 100 | 9.7 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 0.5 | |

| 120 | 8.7 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 0.7 | |

| 150 | 8.6 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 1.4 | |

| [bmim]Cl | 80 | 9.7 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 0.7 |

| 100 | 9.0 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 0.7 | |

| 120 | 9.2 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 0.8 | |

| 150 | 10.4 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 0.2 | |

| [bmim]MeSO4 | 80 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| 100 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 0.6 | |

| 120 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 0.6 | |

| 150 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.2 | |

| Sample | Groups and Interunit Linkages Content, Number per 100 Aromatic Units | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -OCH3 | -C=O | β-O-4 | α-O-4/β-5 | α-O-γ/β-β | |

| DL | 96 | 10.4 | 21.4 | 7.4 | 3.5 |

| IL-DL ([bmim]OAc) | 79 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| IL-DL ([bmim]Cl) | 88 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 3.4 |

| IL-DL ([bmim]MeSO4) | 106 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 8.4 | 1.1 |

| Sample | T, °C | Elemental Composition, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | O | ||

| DL | 62.6 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.1 | |

| IL-DL ([bmim]OAc) | 80 | 63.9 | 7.9 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 25.8 |

| 100 | 64.5 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 25.7 | |

| 120 | 65.1 | 8.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 24.7 | |

| 150 | 65.5 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 19.7 | |

| IL-DL ([bmim]MeSO4) | 80 | 60.2 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 29.3 |

| 100 | 59.2 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 28.5 | |

| 120 | 60.1 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 27.2 | |

| 150 | 58.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 9.9 | 21.9 | |

| IL-DL ([bmim]Cl) | 80 | 64.7 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 28.3 |

| 100 | 64.8 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 28.4 | |

| 120 | 64.9 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 28.3 | |

| 150 | 65.0 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 28.3 | |

| T, °C | Covalently Bound bmim, Number per 100 Aromatic Units | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [bmim]OAc | [bmim]MeSO4 | [bmim]Cl | |

| 80 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.8 |

| 100 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 1.8 |

| 120 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 2.3 |

| 150 | 10.8 | 0.5 | 4.5 |

| No. 1 | Elemental Composition | RDB 2 | Retention Time, min | m/z | Δ, ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [C16H23O2N2]+ | 6.5 | 3.32 | 275.1755 | 0.26 |

| 2 | [C17H25O3N2]+ | 6.5 | 3.41 | 305.1860 | 0.10 |

| 3 | [C27H35O6N2]+ | 11.5 | 7.15 | 483.2487 | 0.51 |

| 4 | [C25H29O5N2]+ | 12.5 | 9.87 | 437.2072 | 0.33 |

| 5 | [C27H33O5N2]+ | 12.5 | 12.07 | 465.2386 | 0.41 |

| 6 | [C28H35O6N2]+ | 12.5 | 12.12 | 495.2491 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belesov, A.V.; Pikovskoi, I.I.; Faleva, A.V.; Kosyakov, D.S. Chemical Transformations of Lignin Under the Action of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ionic Liquids: Covalent Bonding and the Role of Anion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311627

Belesov AV, Pikovskoi II, Faleva AV, Kosyakov DS. Chemical Transformations of Lignin Under the Action of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ionic Liquids: Covalent Bonding and the Role of Anion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311627

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelesov, Artyom V., Ilya I. Pikovskoi, Anna V. Faleva, and Dmitry S. Kosyakov. 2025. "Chemical Transformations of Lignin Under the Action of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ionic Liquids: Covalent Bonding and the Role of Anion" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311627

APA StyleBelesov, A. V., Pikovskoi, I. I., Faleva, A. V., & Kosyakov, D. S. (2025). Chemical Transformations of Lignin Under the Action of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Ionic Liquids: Covalent Bonding and the Role of Anion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311627