Development of Molecular Tools to Identify the Avocado (Persea americana) West-Indian Horticultural Race and Its Hybrids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

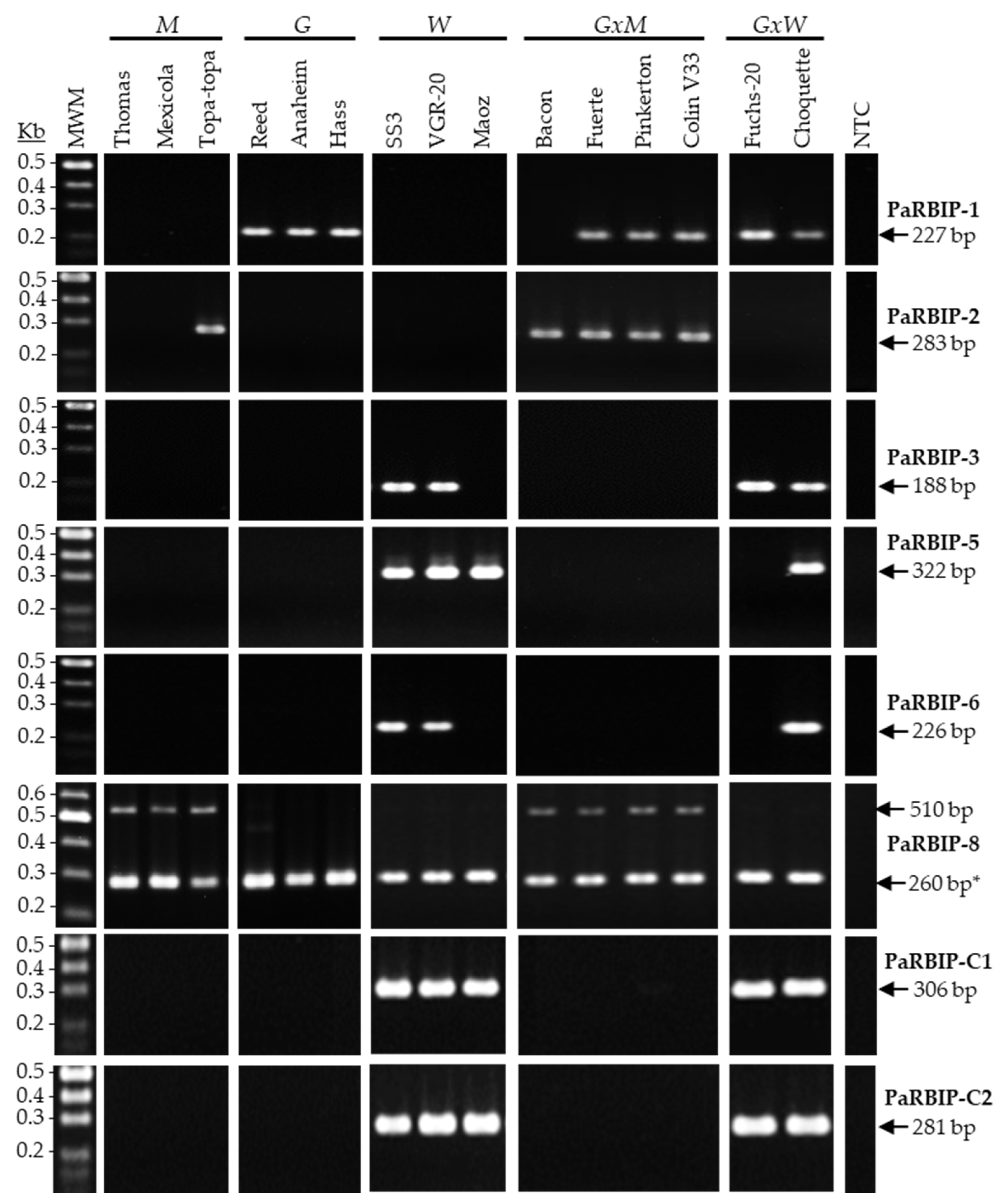

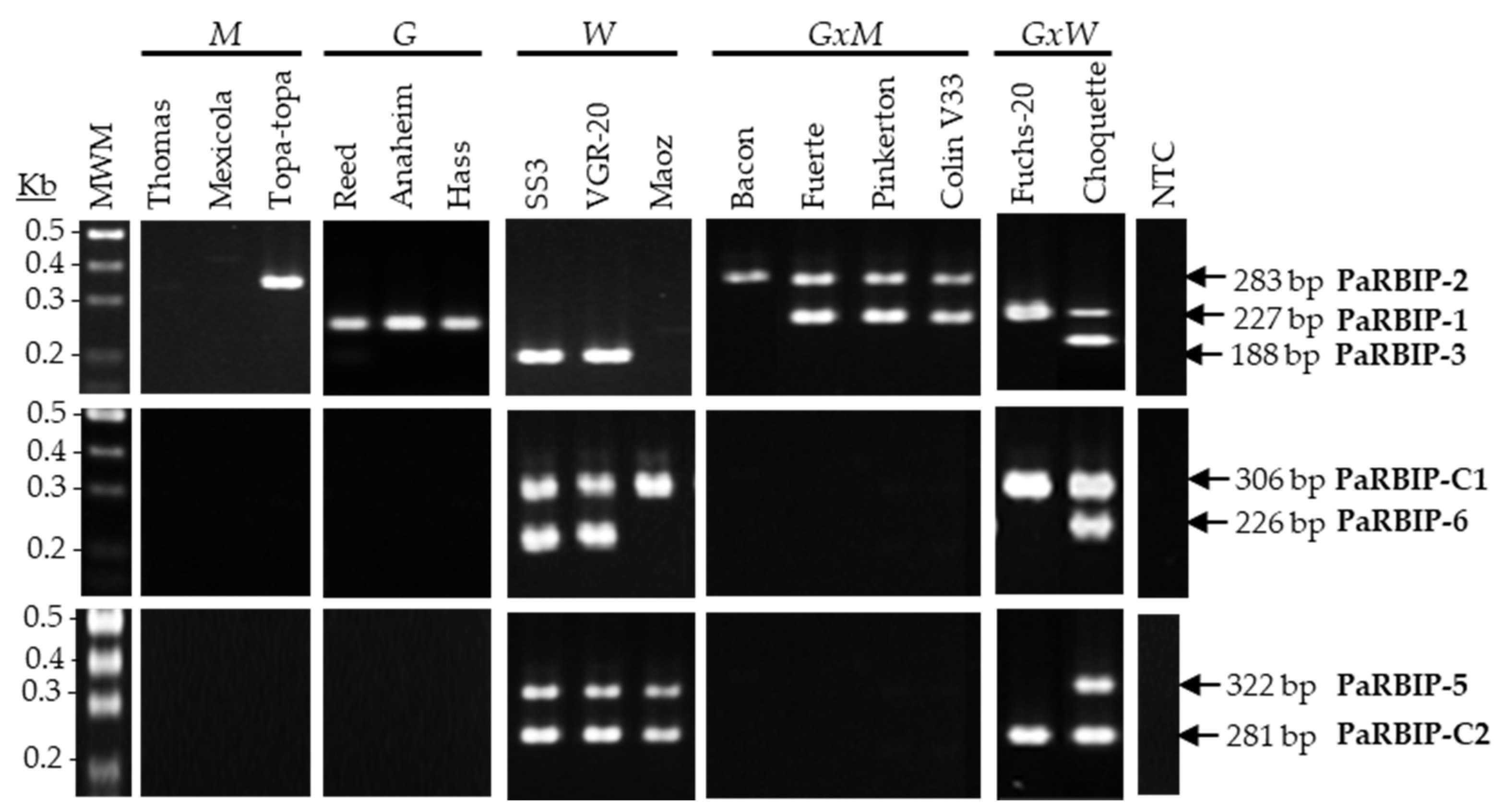

2.1. Suitability of RBIP Molecular Markers for Avocado Horticulture Race Identification

2.2. Sensitivity of PaRBIP Markers in Detecting the West-Indian Genomic Component

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. P. Americana Cultivars and Genomic DNA Purification

4.2. Design of Oligonucleotides for PaRBIP Markers and PCR Amplification

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030; OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-43607-7. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Canario de Estadística (ISTAC). Estadística Anual de Superficies y Producciones de Cultivos. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Rodríguez Sosa, L.; Cáceres Hernández, J.J. Servicio Técnico de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural; Rentabilidad del cultivo del aguacate en Canarias, Ed.; Área de Aguas, Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca del Cabildo Insular de Tenerife: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2014; pp. 1–68. ISBN 978-84-15012-03-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, V.; Chen, H.; Clegg, M. Persea. In Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources. Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Chapter 8; pp. 173–189. ISBN 978-3-642-20446-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, E.; Lavi, U. Avocado Genetics and Breeding. In Breeding Plantation Tree Crops: Tropical Species; Springer New York: New York City, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 247–285. ISBN 978-0-387-71199-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Moreno, J.; Tejedor, M.; Jiménez, C. Effects of Land Use on Soil Degradation and Restoration in the Canary Islands. In Soils of Volcanic Regions in Europe; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 565–579. ISBN 978-3-540-48710-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nektarios, N.K.; Zoi, D. Water Management and Salinity Adaptation Approaches of Avocado Trees: A Review for Hot-Summer Mediterranean Climate. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 252, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis, N.; Suarez, D.L.; Wu, L.; Li, R.; Arpaia, M.L.; Mauk, P. Salt Tolerance and Growth of 13 Avocado Rootstocks Related Best to Chloride Uptake. HortScience 2018, 53, 1737–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Rangel, A.M.; Li, R.; Celis, N.; Suarez, D.L.; Santiago, L.S.; Arpaia, M.L.; Mauk, P.A. The Physiological Response of ‘Hass’ Avocado to Salinity as Influenced by Rootstock. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazare, S.; Cohen, Y.; Goldshtein, E.; Yermiyahu, U.; Ben-Gal, A.; Dag, A. Rootstock-Dependent Response of Hass Avocado to Salt Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, T.W.; Matsumura, M.; Storey, W.B.; Garber, M.J. Chlorine and Other Elements in Avocado Leaves Influenced by Rootstock. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1955, 80, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kadman, A. The Uptake and Accumulation of Sodium in Avocado Seedlings. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1960, 85, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Downton, W.J.S. Growth and Flowering in Salt-Stressed Avocado Trees. Austral. J. Agric. Res. 1978, 29, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo Llobet, L.; Siverio de la Rosa, F.; Rodríguez Pérez, A.; Domínguez Correa, P.; Pérez Zárate, S.; Díaz Hernández, S. Evaluación en Campo de Patrones Clonales de Aguacate de Raza Mexicana y Antillana Tolerante-Resistentes a Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands. In Proceedings of the V World Avocado Congress, Granada–Malaga, Spain, 19–24 October 2003; pp. 573–578. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Normas Técnicas Específicas de Producción Integrada del Aguacate, Mango, Papaya y Piña Tropical en Canarias. Boletín Canar. 2012, 125, 12044–12088. [Google Scholar]

- Gross-German, E.; Viruel, M.A. Molecular Characterization of Avocado Germplasm with a New Set of SSR and EST-SSR Markers: Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, and Identification of Race-Specific Markers in a Group of Cultivated Genotypes. Tree Genet. Genomes 2013, 9, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, B.; Tan, L.; Ma, F.; Zou, M.; Chen, H.; Pei, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Genome-Wide Assessment of Avocado Germplasm Determined from Specific Length Amplified Fragment Sequencing and Transcriptomes: Population Structure, Genetic Diversity, Identification, and Application of Race-Specific Markers. Genes 2019, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Morrell, P.L.; Ashworth, V.E.T.M.; de la Cruz, M.; Clegg, M.T. Tracing the Geographic Origins of Major Avocado Cultivars. J. Hered. 2008, 100, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Antonius, K.; Smýkal, P.; Schulman, A.H. iPBS: A Universal Method for DNA Fingerprinting and Retrotransposon Isolation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Carracedo, M.; Bello Alonso, S.; Brito Cabrera, R.S.; Jiménez-Arias, D.; Pérez Pérez, J.A. Development of Retrotransposon-Based Molecular Markers for Characterization of Persea americana (Avocado) Cultivars and Horticultural Races. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, A.J.; Knox, M.R.; Pearce, S.R.; Ellis, T.H.N. Retrotransposon-Based Insertion Polymorphisms (RBIP) for High Throughput Marker Analysis. Plant J. 1998, 16, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buquicchio, F.; Spruyt, M. Gene Runner, v6.5.52; Hastings Software Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Lahav, E.; Gazit, S. World Listing of Avocado Cultivars According to Flowering Type. Fruits 1994, 49, 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, E.; Lavi, U.; Degani, C.; Zamet, D.; Gazit, S. ‘Adi’, a New Avocado Cultivar. HortScience 1992, 27, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, R.J.; Brown, J.S.; Olano, C.T.; Power, E.J.; Krol, C.A.; Kuhn, D.N.; Motamayor, J.C. Evaluation of Avocado Germplasm Using Microsatellite Markers. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2003, 128, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, U.; Hillel, J.; Vainstein, A.; Lahav, E.; Sharon, D. Application of DNA Fingerprints for Identification and Genetic Analysis of Avocado. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1991, 116, 1078–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California Riverside. Avocado Variety Database. Available online: https://avocado.ucr.edu/avocado-variety-database (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Solares, E.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Balderas, R.F.; Focht, E.; Ashworth, V.E.T.M.; Wyant, S.; Minio, A.; Cantu, D.; Arpaia, M.L.; Gaut, B.S. Insights into the domestication of avocado and potential genetic contributors to heterodichogamy. G3 2023, 13, jkac323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, V.E.T.M.; Clegg, M.T. Microsatellite Markers in Avocado (Persea americana Mill.): Genealogical Relationships Among Cultivated Avocado Genotypes. J. Hered. 2003, 94, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boza, E.J.; Tondo, C.L.; Ledesma, N.; Campbell, R.J.; Bost, J.; Schnell, R.J.; Gutiérrez, O.A. Genetic Differentiation, Races and Interracial Admixture in Avocado (Persea americana Mill.), and Persea spp. Evaluated Using SSR Markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, U.; Sharon, D.; Kaufman, D.; Saada, D.; Chapnik, A.; Zamet, D.; Degani, C.; Lahav, E.; Gazit, S. ’Eden’—A New Avocado Cultivar. HortScience 1997, 32, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadman, A.; Ben-Ya’acov, A. ‘Fuchs-20’ Avocado Rootstock. HortScience 1981, 16, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadman, A.; Ben-Ya’acov, A. G.A.-13 Avocado Rootstock Selection. HortScience 1980, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, E.; Lavi, U.; Zamet, D.; Degani, C.; Gazit, S. Iriet—A New Avocado Cultivar. HortScience 1989, 24, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, L.; Barrientos-Priego, A.; Ben-Ya’acov, A. Study of Avocado Genetic Resources and Related Kinds Species at the Fundacion Salvador Sanchez Colin Cictamex S.C; Memoria Fundación Salvador Sánchez Colin CICTAMEX S.C.: Harinas, Mexico, 1998–2001, 2002; pp. 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ya’acov, A.; Zilberstaine, M.; Goren, M.; Tomer, E. The Israeli Avocado Germplasm Bank: Where and Why the Items Had Been Collected. In Proceedings of the V World Avocado Congress, Granada–Malaga, Spain, 19–24 October 2003; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kadman, A.; Ben-Ya’acov, A. Maoz Avocado Rootstock Selection. HortScience 1980, 15, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo Llobet, L.; Rodríguez Pérez, A.; Siverio de la Rosa, F.; Díaz Hernández, S.; Domínguez Correa, P. Uso Potencial de la raza Antillana Como Fuente de Resistencia a la Podredumbre Radicular del Aguacate. In Proceedings of the V World Avocado Congress, Granada–Malaga, Spain, 19–24 October 2003; pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, O.; Fletcher, S.J.; Hayward, A.; Shaw, L.M.; Masouleh, A.K.; Furtado, A.; Henry, R.J.; Mitter, N. A haplotype resolved chromosomal level avocado genome allows analysis of novel avocado genes. Hortic Res. 2022, 30, uhac157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Cortés, A.J.; López-Hernández, F.; Delgadillo-Durán, P.; Cerón-Souza, I.; Reyes-Herrera, P.H.; Navas-Arboleda, A.A.; Yockteng, R. Pleistocene-dated genomic divergence of avocado trees supports cryptic diversity in the Colombian germplasm. Tree Genet. Genomes 2023, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RBIP Assay | Primer ID | Sequence (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) 1 | Expected Length (bp) | Multiplex Assay | Primer Conc. in Multiplex (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaRBIP-1 | PaRBIP-1F | CCAACCAATCTATTTATTATGGAATCT | 60.6 | 227 | A | 0.4 |

| PaRBIP-1R | CCAAGCTCTAAGAAAGGAAAACC | 61.7 | ||||

| PaRBIP-2 | PaRBIP-2F | TGTCCCTCGTGGTTTATTCTATC | 61.7 | 283 | A | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-2R | AATGTAGGCTCTAAGAAAGGAAATAC | 60.1 | ||||

| PaRBIP-3 | PaRBIP-3F | AGCTAACCTTGGAGCCTTCTC | 62.5 | 188 | A | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-3R | CTAGCTGGACTGGATTGATGG | 62.0 | ||||

| PaRBIP-5 | PaRBIP-5F | TGTCGGGGTGACAAGATATTTC | 62.8 | 322 | B | 0.3 |

| PaRBIP-5R | AACTCACCTATAAGGGTCTAATCAAC | 60.9 | ||||

| PaRBIP-6 | PaRBIP-6F | CTATCCACTTCTTTGCGGACTAC | 62.0 | 226 | C | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-6R | CTCTATAGTCGATGTGGGACTCC | 62.1 | ||||

| PaRBIP-8 | PaRBIP-8F | AGAAGATGGACAGTTCGGATCA | 65.3 | 260 + 510 | NA | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-8R | AACGAGAGTGGACGTTGACCT | 65.1 | ||||

| PaRBIP-C1 | PaRBIP-C1F | TGCCCCTACATTTGGAGATTC | 62.8 | 306 | C | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-C1R | GATGGGTCATGGATGGCTAAC | 63.2 | ||||

| PaRBIP-C2 | PaRBIP-C2F | ACGAGATTGGATAGCACCATGT | 63.4 | 281 | B | 0.2 |

| PaRBIP-C2R | CCTTGAGGATTCACCATCATGT | 62.8 |

| Cultivar | Source | PaRBIP Markers | This Study | Previously Reported 1 | References | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | C1 | C2 | 8 | |||||

| A3 | ICIA 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| Adi | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | G/GxM | [23,24] |

| Anaheim | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | G | [23,25,26,27,28] |

| Arona | Agro-Rincón | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | M | [23,27] |

| BA2 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| Bacon | Agro-Rincón | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M/GxM | [23,25,27,28,29] |

| BL-5552 | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [29] |

| BL667 | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [29] |

| Choquette | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | GxW | [23,25,27,30] |

| Colin V-33 | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [23,27] |

| Duke Parent | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [23,25,29] |

| Duke-7 | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | M | [14,29] |

| Eden | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [31] |

| Ettinger | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | GxM | [23,25,27,29,30] |

| Fuchs-20 | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | GxW | [27,32] |

| Fuerte | Agro-Rincón | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [23,28,29] |

| G-6 | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [29] |

| G.A-13 | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | non-W (GxM)xW | M | [33] |

| Gallo 2 | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | N/A | N/A |

| Gallo 3 | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM)xW | N/A | N/A |

| Gallo 4 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| Hass | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | G/GxM | [23,25,27,28,29] |

| Horshim | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [23,25] |

| Iriet | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [25,34] |

| Jim | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (M) | M/GxM | [23,25,27] |

| Julian | ICIA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | non-W (M)xW | N/A | N/A |

| Lamb-Hass | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [25,29] |

| Lonjas | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | M | [35] |

| Lula | La Mayora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | non-W (M)xW | GxM/GxW | [25,27,36] |

| M1 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| Maoz | La Mayora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | W | [14,23,27,37] |

| Mexicola | La Mayora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [23,25,27,30] |

| Negra de la Cruz | La Mayora | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | M/hybrid | [35,36] |

| OA-184 | La Mayora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | GxM | [29] |

| Orotava | ICIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | G | [23,27] |

| Pinkerton | Agro-Rincón | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | GxM | [23,25,27,28,29,30] |

| Puebla | Agro-Rincón | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (GxM) | M/GxM | [23,25,27] |

| Reed | Agro-Rincón | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G) | G | [23,25,26,27,28] |

| Rincoatl | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [35] |

| Rincon | ICIA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | N/A | N/A |

| Schmidt | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | G/M | [26,27] |

| Scott | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [27] |

| Shepard | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (M) | G | [27] |

| SS3 | Agro-Rincón | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | W | [38] |

| T23 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| Taro | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | N/A | N/A |

| Taro H25 | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | W | [38] |

| Taro H27 | ICIA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | non-W (G)xW | W | [38] |

| Thomas | La Mayora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [27,29] |

| Topa–Topa | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [23,25,27,28,29] |

| Toro Canyon | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [29,36] |

| V1 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| De La Verruga | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | N/A | N/A |

| VGR20 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | W | [38] |

| VGR32 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | W | [38] |

| VGR38 | ICIA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | W | W | [38] |

| Waterhole | La Mayora | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M | [27,29] |

| Zutano | La Mayora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | non-W (M) | M/GxM | [25,28,29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Carracedo, M.; Bello Alonso, S.; Ramos Luis, A.; Escuela Escobar, A.; Jiménez Arias, D.; Pérez Pérez, J.A. Development of Molecular Tools to Identify the Avocado (Persea americana) West-Indian Horticultural Race and Its Hybrids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311510

González Carracedo M, Bello Alonso S, Ramos Luis A, Escuela Escobar A, Jiménez Arias D, Pérez Pérez JA. Development of Molecular Tools to Identify the Avocado (Persea americana) West-Indian Horticultural Race and Its Hybrids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311510

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Carracedo, Mario, Samuel Bello Alonso, Anselmo Ramos Luis, Ainhoa Escuela Escobar, David Jiménez Arias, and José Antonio Pérez Pérez. 2025. "Development of Molecular Tools to Identify the Avocado (Persea americana) West-Indian Horticultural Race and Its Hybrids" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311510

APA StyleGonzález Carracedo, M., Bello Alonso, S., Ramos Luis, A., Escuela Escobar, A., Jiménez Arias, D., & Pérez Pérez, J. A. (2025). Development of Molecular Tools to Identify the Avocado (Persea americana) West-Indian Horticultural Race and Its Hybrids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311510