Consumption of Sericin Enhances the Bioavailability and Metabolic Efficacy of Chromium Picolinate in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

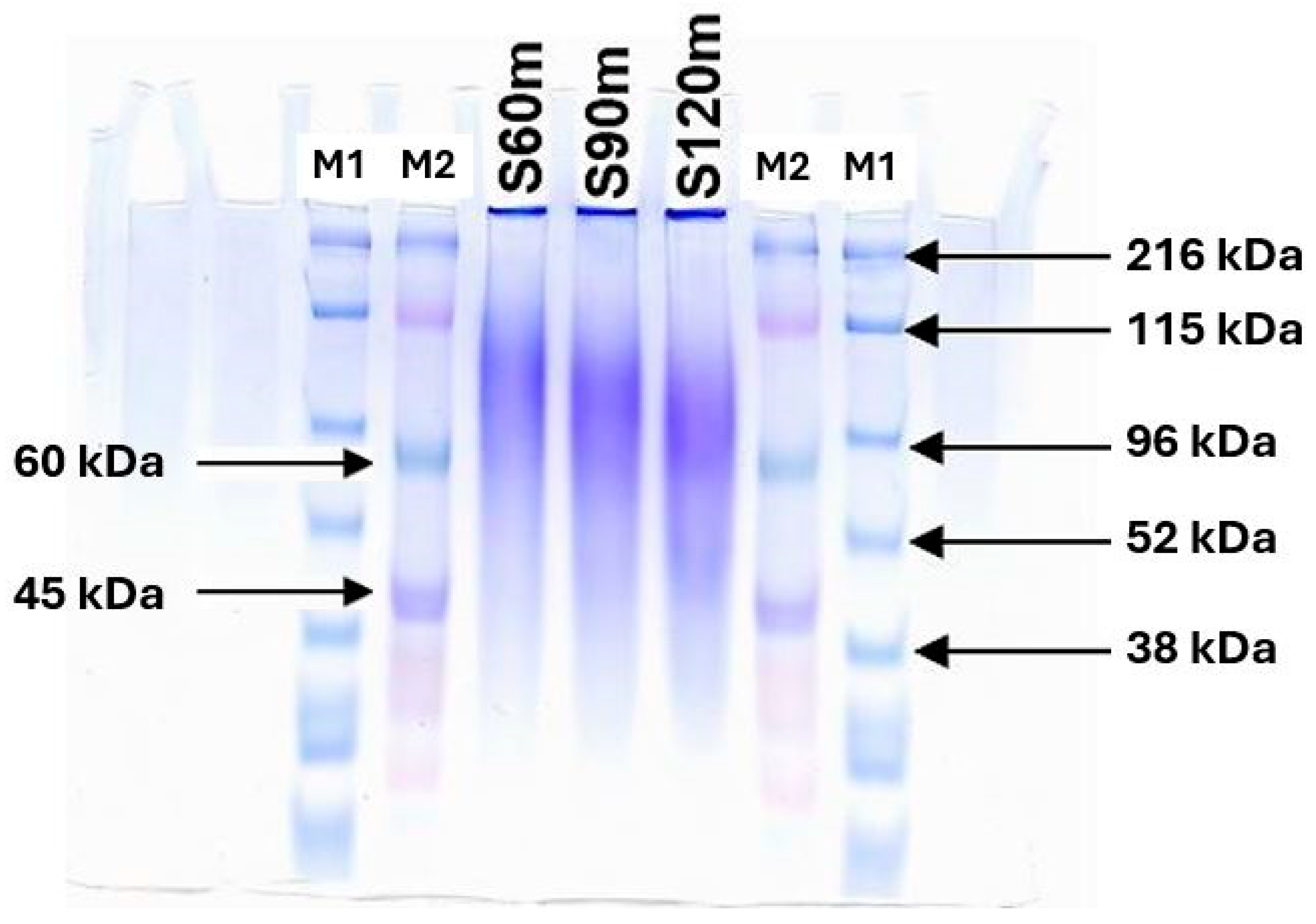

2.1. Characteristics of SS

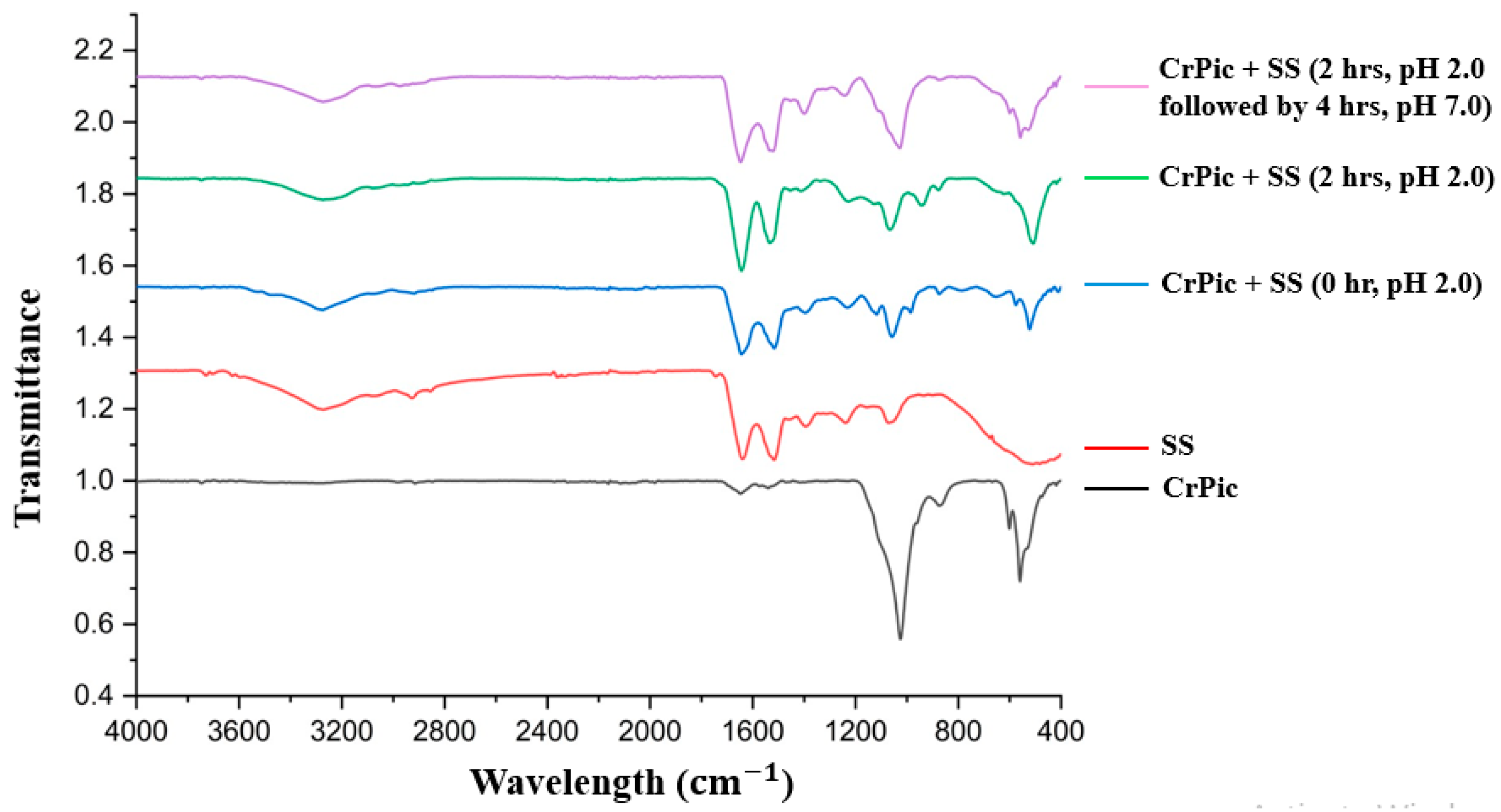

2.2. SS-Cr Chelating Ability at Stomach and Intestinal pH Levels

2.3. Effects on Body and Organ Weight

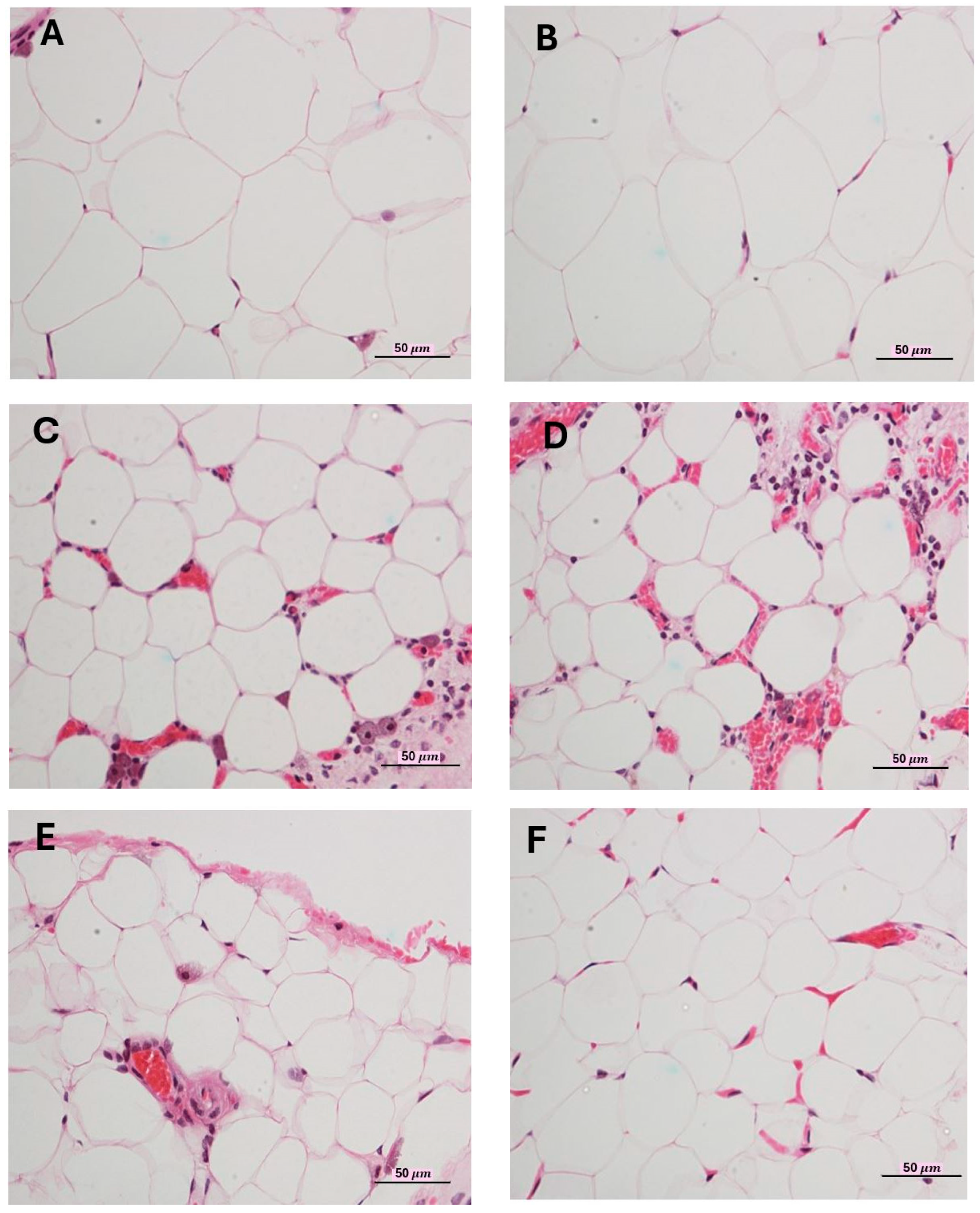

2.4. Clinical Chemistry Analysis

2.5. Effects on Adipocytes Size

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Silk SS and Its Characteristics

4.2. Sericin Characterization

4.2.1. Molecular Weight Determination

4.2.2. Amino Acid Analysis

4.3. FTIR Analysis of SS-Cr Chelating Ability at Stomach and Intestinal pH Levels

4.4. Animals

4.5. SS Supplementation at Different Concentrations on Cr Functionality in Rats

4.6. Analysis of Blood Clinical Chemistry and Cr Levels in the Kidneys and Livers

4.7. Weights of Internal Organs and Characteristics of Abdominal Adipose Tissue (Omentum)

4.8. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.M.; Boyle, J.P.; Thompson, T.J.; Gregg, E.W.; Williamson, D.F. Effect of BMI on lifetime risk for diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1562–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Ma, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus Promotes the Development of Atherosclerosis: The Role of NLRP3. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 900254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniki, Y.; Kato, T.; Irie, H.; Mizuta, H.; Takagi, K. Diabetes with hyperlipidemia: A risk factor for developing joint contractures secondary to immobility in rat knee joints? J. Orthop. Sci. 2005, 10, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloubani, A.; Nimer, R.; Samara, R. Relationship between Hyperlipidemia, Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Systematic Review. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, M.-E.; Tchernof, A.; Després, J.-P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1477–1500, Erratum in Circ. Res. 2020, 127, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzka, A.; Kapusniak, K.; Zielińska, D.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Kapusniak, J.; Barczyńska-Felusiak, R. The Importance of Micronutrient Adequacy in Obesity and the Potential of Microbiota Interventions to Support It. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidi, F. A comparative study to assess the use of chromium in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari Seyedmahalle, M.; Haghpanah Jahromi, F.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Sohrabi, Z. Effect of Chromium Supplementation on Body Weight and Body Fat: A Systematic Review of Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trials. Int. J. Nutr. Sci. 2022, 7, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, B.; Aggarwal, A.; Sandhir, R. Chromium picolinate attenuates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2013, 27, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.T.; Guo, W.L.; Yang, Z.Y.; Chen, F.; Lin, T.T.; Li, W.L.; Lv, X.C.; Rao, P.F.; Ai, L.Z.; Ni, L. Intestinal microbiomics and liver metabolomics insights into the preventive effects of chromium (III)-enriched yeast on hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.L.; Chen, M.; Pan, W.L.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.X.; Lin, Y.C.; Li, L.; Liu, B.; Bai, W.D.; Zhang, Y.Y.; et al. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic mechanism of organic chromium derived from chelation of Grifola frondosa polysaccharide-chromium (III) and its modulation of intestinal microflora in high fat-diet and STZ-induced diabetic mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, E.; Krejpcio, Z.; Okulicz, M.; Śmigielska, H. Chromium(III) Glycinate Complex Supplementation Improves the Blood Glucose Level and Attenuates the Tissular Copper to Zinc Ratio in Rats with Mild Hyperglycaemia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 193, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, J.; Guo, Z.; Fu, Q. Bioaccumulation of dietary CrPic, Cr(III) and Cr(VI) in juvenile coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 240, 113692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, A.D.; Tare, V.; Bose, P. Extent of oxidation of Cr(III) to Cr(VI) under various conditions pertaining to natural environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 128, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, M.; Hong, R.; Chen, H. Preparation of a Momordica charantia L. polysaccharide-chromium (III) complex and its anti-hyperglycemic activity in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumina, J.; Harizal, H. Dermatologic Toxicities and Biological Activities of Chromium. In Trace Metals in the Environment—New Approaches and Recent Advances; Murillo-Tovar, M.A., Saldarriaga Noreña, H.A., Saeid, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Russell, J.C.; Hulver, M.; Cefalu, W.T. Chromium Picolinate Enhances Skeletal Muscle Cellular Insulin Signaling In Vivo in Obese, Insulin-Resistant JCR:LA-cp Rats1. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manygoats, K.R.; Yazzie, M.; Stearns, D.M. Ultrastructural damage in chromium picolinate-treated cells: A TEM study. Transmission electron microscopy. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 7, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja, O.; Yeghiazaryan, K. Opinion controversy to chromium picolinate therapy’s safety and efficacy: Ignoring ‘anecdotes’ of case reports or recognising individual risks and new guidelines urgency to introduce innovation by predictive diagnostics? EPMA J. 2012, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Pan, Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, H. Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus polysaccharides-chromium (III) complex in type 2 diabetic mice and its sub-acute toxicity evaluation in normal mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108 Pt B, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ye, H.; Cui, J.; Chi, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, P. Hypolipidemic effect of chromium-modified enzymatic product of sulfated rhamnose polysaccharide from Enteromorpha prolifera in type 2 diabetic mice. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, P.; Zheng, T. Novel Applications of Silk Proteins Based on Their Interactions with Metal Ions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Li, M.; Xie, R. Preparation and Structure of Porous Silk Sericin Materials. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2005, 290, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Kato, N.; Watanabe, H.; Yamada, H. Silk protein, sericin, suppresses colon carcinogenesis induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine in mice. Oncol. Rep. 2000, 7, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.Y.; Moon, J.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Lee, K.G.; Yeo, J.H.; Kweon, H.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Cho, C.S. Preparation of self-assembled silk sericin nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2003, 32, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wen, P.; Qin, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Ye, Y. Toxicological evaluation of water-extract sericin from silkworm (Bombyx mori) in pregnant rats and their fetus during pregnancy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 982841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Yamada, H.; Kato, N. Consumption of silk protein, sericin elevates intestinal absorption of zinc, iron, magnesium and calcium in rats. Nutr. Res. 2000, 20, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpeanchob, N.; Trisat, K.; Duangjai, A.; Tiyaboonchai, W.; Pongcharoen, S.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Sericin reduces serum cholesterol in rats and cholesterol uptake into Caco-2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12519–12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkon, W.; Aonsri, C.; Tiyaboonchai, W.; Pongcharoen, S.; Sutheerawattananonda, M.; Limpeanchob, N. Sericin consumption suppresses development and progression of colon tumorigenesis in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-treated rats. Biologia 2012, 67, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakul, K.; Takenaka, S.; Peterbauer, C.; Haltrich, D.; Techapun, C.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Chaiyaso, T. Functional modification of thermostable alkaline protease from Bacillus halodurans SE5 for efficient production of antioxidative and ACE-inhibitory peptides from sericin. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 54, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhong, H.; Pi, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z. Oral sericin ameliorates type 2 diabetes through passive intestinal and bypass transport into the systemic circulation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 332, 118342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubulikasimu, A.; Omar, A.; Gao, Y.; Mukhamedov, N.; Arken, A.; Wali, A.; Mirzaakhmedov, S.Y.; Yili, A. Antioxidant Hydrolysate of Sericin from Bombyx mori Cocoons. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2021, 57, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocharus, C.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Hypoglycemic Ability of Sericin-Derived Oligopeptides (SDOs) from Bombyx mori Yellow Silk Cocoons and Their Physiological Effects on Streptozotocin (STZ)-Induced Diabetic Rats. Foods 2024, 13, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocharus, C.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Preventive and Therapeutic Effects of Sericin-Derived Oligopeptides (SDOs) from Yellow Silk Cocoons on Blood Pressure Lowering in L-NAME-Induced Hypertensive Rats. Foods 2025, 14, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.W.; Yang, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Yun, H.; Kim, M.; Lee, K. Chromium(VI) Adsorption Behavior of Silk Sericin Beads. Int. J. Ind. Entomol. 2013, 26, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.W.; Shin, M.; Yun, H.; Lee, K. Preparation of Silk Sericin/Lignin Blend Beads for the Removal of Hexavalent Chromium Ions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Rathinam, K.; Kasher, R.; Arnusch, C.J. Hexavalent chromium ion and methyl orange dye uptake via a silk protein sericin–chitosan conjugate. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 27027–27036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrade, J.; Silva, M.; Gimenes, M.; Vieira, M. Bioadsorption of trivalent and hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions by sericin-alginate particles produced from Bombyx mori cocoons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25967–25982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Xu, Z.; Gao, S.; Meng, K.; Zhao, H. Green Extraction and Separation of Silk Sericin with High and Low Molecular Weight and Their Gelling Performances. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Agrawal, A.; Rangi, A. Extraction and characterization of silk sericin. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2014, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.-Y. Enzymatic production of bioactive peptides from sericin recovered from silk industry wastewater. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaciu, A.A.; Aboul-Enein, H.; Fleschin, E. FT-IR Spectrophotometric Analysis of Chromium (Tris) Picolinate and its Pharmaceutical Formulations. Anal. Lett. 2006, 39, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, K.W.; Cromwell, G.L. Effects of dietary chromium picolinate supplementation on growth, carcass characteristics, and accretion rates of carcass tissues in growing-finishing swine. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 3351–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasten, D.L.; Hegsted, M.; Keenan, M.J.; Morris, G.S. Effects of various forms of dietary chromium on growth and body composition in the rat. Nutr. Res. 1997, 17, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoikon, E.K.; Fernandez, J.M.; Southern, L.L.; Thompson, D.L., Jr.; Ward, T.L.; Olcott, B.M. Effect of chromium tripicolinate on growth, glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, plasma metabolites, and growth hormone in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleman, S.L.; Boleman, S.J.; Bidner, T.D.; Southern, L.L.; Ward, T.L.; Pontif, J.E.; Pike, M.M. Effect of chromium picolinate on growth, body composition, and tissue accretion in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2033–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, T.G.; Southern, L.L.; Ward, T.L.; Thompson, D.L., Jr. Effect of chromium picolinate on growth and serum and carcass traits of growing-finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1993, 71, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, X. Change trends of organ weight background data in sprague dawley rats at different ages. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013, 26, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Z.A.; Rayner, D.V.; Rozman, J.; Klingenspor, M.; Mercer, J.G. Normal distribution of body weight gain in male Sprague-Dawley rats fed a high-energy diet. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-D.; Zhong, Z.-H.; Weng, Y.-J.; Wei, Z.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Degraded Sericin Significantly Regulates Blood Glucose Levels and Improves Impaired Liver Function in T2D Rats by Reducing Oxidative Stress. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, L.Y.; Wang, M.Q.; Xu, Z.R.; Gu, L.Y. Efficacy of chromium(III) supplementation on growth, body composition, serum parameters, and tissue chromium in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2007, 119, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.B. The bioinorganic chemistry of chromium(III). Polyhedron 2001, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookstein, O.; Shimoni, E.; Eliaz, D.; Kaplan-Ashiri, I.; Carmel, I.; Shimanovich, U. Metal ions guide the production of silkworm silk fibers. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aad, R.; Dragojlov, I.; Vesentini, S. Sericin Protein: Structure, Properties, and Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, A.; Bagchi, M.; Preuss, H.G.; Zafra-Stone, S.; Ahmad, T.; Bagchi, D. Chapter 8—Benefits of chromium(III) complexes in animal and human health. In The Nutritional Biochemistry of Chromium (III), 2nd ed.; Vincent, J.B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 251–278. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, S.; Ocasio Quinones, G.A. Chromium Deficiency. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.A. Effects of chromium on body composition and weight loss. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.B. Recent advances in the nutritional biochemistry of trivalent chromium. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C. Chromium as a supplement. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1999, 19, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, M.D.; Wood, C.M.; Harper, A.F.; Kornegay, E.T.; Anderson, R.A. Dietary chromium picolinate additions improve gain:feed and carcass characteristics in growing-finishing pigs and increase litter size in reproducing sows. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Cottrell, J.J.; Wijesiriwardana, U.; Kelly, F.W.; Chauhan, S.S.; Pustovit, R.V.; Gonzales-Rivas, P.A.; DiGiacomo, K.; Leury, B.J.; Celi, P.; et al. Effects of chromium supplementation on physiology, feed intake, and insulin related metabolism in growing pigs subjected to heat stress. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2017, 1, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refaie, F.M.; Esmat, A.Y.; Mohamed, A.F.; Aboul Nour, W.H. Effect of chromium supplementation on the diabetes induced-oxidative stress in liver and brain of adult rats. Biometals 2009, 22, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, R.; Sari, M.A.; Erten, F.; Er, B.; Tuzcu, M.; Orhan, C.; Deeh, P.B.D.; Sahin, N.; Cinar, V.; Komorowski, J.R.; et al. The effects of chromium picolinate on glucose and lipid metabolism in running rats. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 58, 126434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Xu, R.; Yin, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y. Pancreatic endocrine and exocrine signaling and crosstalk in physiological and pathological status. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chun, Y.-S.; Yoon, N.; Kim, B.; Choi, K.; Ku, S.-K.; Lee, N. Effects of Black Cumin Seed Extract on Pancreatic Islet β-Cell Proliferation and Hypoglycemic Activity in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yi, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wen, P.; Qin, G. Exploring the Mechanism of Action of Sericin in Ameliorating non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice Based on the Nrf2- GPX4/NF-κB p65 Pathway. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241287061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.J.; Milner, R.D. Insulin as a growth factor. Pediatr. Res. 1985, 19, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, N.J.; Penque, B.A.; Habegger, K.M.; Sealls, W.; Tackett, L.; Elmendorf, J.S. Chromium enhances insulin responsiveness via AMPK. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y.; Kakehi, S.; Xu, Y.; Tsujimoto, K.; Sasaki, M.; Ogawa, H.; Kato, N. Consumption of sericin reduces serum lipids, ameliorates glucose tolerance and elevates serum adiponectin in rats fed a high-fat diet. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 1534–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, P.U.; Egbugara, M.N.; Ogboi, J.S.; Ajah, L.O.; Nwagha, U.I.; Ugwu, E.O.; Ezugwu, E.C. Atherogenic Index, Cardiovascular Risk Ratio, and Atherogenic Coefficient as Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease in Pre-eclampsia in Southeast Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 27, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.H.; Bhardwaj, S.H.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Bhatnagar, M.K.; Tyagi, S.C. Atherogenic index of plasma, castelli risk index and atherogenic coefficient-new parameters in assessing cardiovascular risk. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kiokias, S.; Proestos, C.; Oreopoulou, V. Effect of Natural Food Antioxidants against LDL and DNA Oxidative Changes. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borén, J.; Chapman, M.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Packard, C.J.; Bentzon, J.F.; Binder, C.J.; Daemen, M.J.; Demer, L.L.; Hegele, R.A.; Nicholls, S.J.; et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2313–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, M.; Barrett, T.J.; Fisher, E.A. HDL and Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Clark, S.; Ren, J.; Sreejayan, N. Molecular mechanisms of chromium in alleviating insulin resistance. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, T.; Liang, W.A.; Wang, Y.; Feng, M.; Sun, J. Silk sericin as building blocks of bioactive materials for advanced therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2023, 353, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genchi, G.; Lauria, G.; Catalano, A.; Carocci, A.; Sinicropi, M.S. The Double Face of Metals: The Intriguing Case of Chromium. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechova, A.; Pavlata, L. Chromium as an essential nutrient: A review. Vet. Med. 2007, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Bryden, N.A.; Polansky, M.M. Lack of toxicity of chromium chloride and chromium picolinate in rats. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1997, 16, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F. Homologous physiological effects of phenformin and chromium picolinate. Med. Hypotheses 1993, 41, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, R.I.; Geller, J.; Evans, G.W. The effect of chromium picolinate on serum cholesterol and apolipoprotein fractions in human subjects. West. J. Med. 1990, 152, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, D.; Hewlings, S.; Kalman, D. Body Composition Changes in Weight Loss: Strategies and Supplementation for Maintaining Lean Body Mass, a Brief Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; He, Y.; Song, C.; Liu, Y. Effect of sericin on diabetic hippocampal growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor 1 axis. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, D.; Yang, S.; Cheng, L.; Xing, E.; Chen, Z. Sericin enhances the insulin-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in the liver of a type 2 diabetes rat model. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 3345–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampawong, S.; Isarangkul, D.; Aramwit, P. Sericin ameliorated dysmorphic mitochondria in high-cholesterol diet/streptozotocin rat by antioxidative property. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 411–421, Erratum in Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, NP1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapphanichayakool, P.; Sutheerawattananonda, M.; Limpeanchob, N. Hypocholesterolemic effect of sericin-derived oligopeptides in high-cholesterol fed rats. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 71, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; He, Z.; Sun, R.; Ge, S.; Zhang, Z. Chromium picolinate supplementation for overweight or obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, Cd010063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaats, G.R.; Blum, K.; Pullin, D.; Keith, S.C.; Wood, R. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study of the effects of chromium picolinate supplementation on body composition: A replication and extension of a previous study. Curr. Ther. Res.-Clin. Exp. 1998, 59, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, M.; Lou, X.; Zhao, B.; Ma, Q.; Bian, Y.; Mi, X. Evaluation of Hypoglycemic Activity and Sub-Acute Toxicity of the Novel Biochanin A-Chromium(III) Complex. Molecules 2022, 27, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, E.; Alegría, A.; Barberá, R.; Farré, R. Casein phosphopeptides released by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of infant formulas and their potential role in mineral binding. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Sandström, B.; Lönnerdal, B. The effect of casein phosphopeptides on zinc and calcium absorption from high phytate infant diets assessed in rat pups and Caco-2 cells. Pediatr. Res. 1996, 40, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, A.; Castro, F.; Rocha, F.; Oliveira, A.L. Recent Advances in Silk Sericin/Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.-T.; Zhang, Y.-Q. The potential of silk sericin protein as a serum substitute or an additive in cell culture and cryopreservation. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, R.I.; Brancalhão, R.M.; Ribeiro, L.F.; Natali, M.R. Silkworm Sericin: Properties and Biomedical Applications. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8175701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Bhattacharya, B.; Mukherjee, B.; Manna, B.; Sinha, M.; Chowdhury, J.; Chowdhury, S. Role of chromium supplementation in Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talab, A.T.; Abdollahzad, H.; Nachvak, S.M.; Pasdar, Y.; Eghtesadi, S.; Izadi, A.; Aghdashi, M.A.; Mohammad Hossseini Azar, M.R.; Moradi, S.; Mehaki, B.; et al. Effects of Chromium Picolinate Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Cardillo, S.; Volger, S.; Bloedon, L.T.; Anderson, R.A.; Boston, R.; Szapary, P.O. Chromium picolinate does not improve key features of metabolic syndrome in obese nondiabetic adults. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2009, 7, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkorn, W.; Limpeanchob, N.; Tiyaboonchai, W.; Pongcharoen, S.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Effects of silk sericin on the proliferation and apoptosis of colon cancer cells. Biol. Res. 2012, 45, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.; Osborn, M. The reliability of molecular weight determinations by dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 1969, 244, 4406–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Commission of The European Communities. Commission Directive 98/64/EC of 3 September 1998: Establishing Community Methods of Analysis for the Determination of Amino Acids, Crude Oils and Fats, and Starch; L257; The Commission of The European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1998; Annex Part A; pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Šíma, M.; Kutinová-Canová, N.; Ryšánek, P.; Hořínková, J.; Moškořová, D.; Slanař, O. Gastric pH in Rats: Key Determinant for Preclinical Evaluation of pH-dependent Oral Drug Absorption. Prague Med. Rep. 2019, 120, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.L.; Basit, A.W.; Murdan, S. Measurements of rat and mouse gastrointestinal pH, fluid and lymphoid tissue, and implications for in-vivo experiments. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008, 60, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodewald, R. pH-dependent binding of immunoglobulins to intestinal cells of the neonatal rat. J. Cell Biol. 1976, 71, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, Q.; Daş, G.; Metges, C.C. REVIEW: The pig as a model for humans: Effects of nutritional factors on intestinal function and health1. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94 (Suppl. 3), 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manupa, W.; Wongthanyakram, J.; Jeencham, R.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Storage stability and antioxidant activities of lutein extracted from yellow silk cocoons (Bombyx mori) in Thailand. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavalittumrong, P.; Chivapat, S.; Attawish, A.; Bansiddhi, J.; Phadungpat, S.; Chaorai, B.; Butraporn, R. Chronic toxicity study of Portulaca grandiflora Hook. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 90, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Bryden, N.A.; Polansky, M.M.; Gautschi, K. Dietary chromium effects on tissue chromium concentrations and chromium absorption in rats. J. Trace Elem. Exp. Med. 1996, 9, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorhem, L.; Engman, J.; Arvidsson, B.M.; Åsman, B.; Åstrand, C.; Gjerstad, K.; Haugsnes, J.; Heldal, V.; Holm, K.; Jensen, A.; et al. Determination of Lead, Cadmium, Zinc, Copper, and Iron in Foods by Atomic Absorption Spectrometry after Microwave Digestion: NMKL1 Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 2000, 83, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC International. Method 999.10: Lead, Cadmium, Zinc, Copper, and Iron in Foods. Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry after Microwave Digestion. In Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; AOAC International, Ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2003; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Tocharus, C.; Prum, V.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Oral Toxicity and Hypotensive Influence of Sericin-Derived Oligopeptides (SDOs) from Yellow Silk Cocoons of Bombyx mori in Rodent Studies. Foods 2024, 13, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Shinohara, K.; Kitamura, N.; Nakamura, A.; Onoue, A.; Tanaka, K.; Hirayama, A.; Aw, W.; Nakamura, S.; Ogawa, Y.; et al. Metabolic Effects of Bee Larva-Derived Protein in Mice: Assessment of an Alternative Protein Source. Foods 2021, 10, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitry, M.Y.; Marie Therèse, B.A.; Josiane Edith, D.M.; Emmanuel, P.A.; Armand, A.B.; Nicolas, N.Y. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of vegetal milk produced with Mucuna pruriens L. seed in rats fed a high-fat diet. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Sodhi, K.; Puri, N.; Monu, S.R.; Rezzani, R.; Abraham, N.G. High fat diet enhances cardiac abnormalities in SHR rats: Protective role of heme oxygenase-adiponectin axis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2011, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Meireles, M.; Norberto, S.; Leite, J.; Freitas, J.; Pestana, D.; Faria, A.; Calhau, C. High-fat diet-induced obesity Rat model: A comparison between Wistar and Sprague-Dawley Rat. Adipocyte 2016, 5, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubrecht, R.C.; Carter, E. The 3Rs and Humane Experimental Technique: Implementing Change. Animals 2019, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, M.; Gromadziński, L.; Cholewińska, E.; Ognik, K.; Fotschki, B.; Juśkiewicz, J. Dietary Effects of Chromium Picolinate and Chromium Nanoparticles in Wistar Rats Fed with a High-Fat, Low-Fiber Diet: The Role of Fat Normalization. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stępniowska, A.; Tutaj, K.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Ognik, K. Effect of a high-fat diet and chromium on hormones level and Cr retention in rats. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Toxicology Program. NTP toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of chromium picolinate monohydrate (CAS No. 27882-76-4) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (feed studies). Natl. Toxicol. Program Tech. Rep. Ser. 2010, 556, 1–194. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, S.; Raveendran, R.; Kesavan, R. Blood sample collection in small laboratory animals. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010, 1, 87–93, Erratum in J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2017, 8, 153. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization; International Electrotechnical Commission. General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories (ISO/IEC Standard No. 17025:2005). 2005. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:17025:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

| Amino Acids | Concentration (mg 100 g−1) | Limit of Detection (LOD) (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspartic acid | 18,373.10 | 100 |

| Threonine | 7726.64 | 100 |

| Serine | 32,472.87 | 100 |

| Glutamic acid | 5084.54 | 50 |

| Glycine | 8853.44 | 50 |

| Alanine | 3184.83 | 50 |

| Cystine | <200.00 | 100 |

| Valine | 4345.81 | 50 |

| Methionine | Not Detected | 100 |

| Isoleucine | 691.44 | 50 |

| Leucine | 1200.34 | 50 |

| Tyrosine | 5402.71 | 100 |

| Phenylalanine | 462.93 | 100 |

| Histidine | 1877.87 | 50 |

| Hydroxylysine | Not Detected | 100 |

| Lysine | 3129.27 | 50 |

| Arginine | 4144.50 | 100 |

| Hydroxyproline | Not Detected | 200 |

| Proline | 556.41 | 100 |

| Tryptophan | 549.47 | 50 |

| Parameter | Control | BW | BW | BW | BW | BW BW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight (g) | 330.00 ± 15.49 | 325.00 ± 20.74 | 341.67 ± 16.02 | 325.00 ± 30.82 | 355.00 ± 22.58 | 336.67 ± 18.62 |

| Final body weight (g) | 451.67 ± 18.35 | 431.67 ± 21.37 | 445.00 ± 24.29 | 423.33 ± 42.27 | 430.00 ± 55.14 | 430.00 ± 33.47 |

| Daily feed intake (g per day) | 19.76 ± 1.42 | 18.57 ± 0.93 | 19.52 ± 1.73 | 18.93 ± 1.42 | 18.81 ± 0.81 | 18.45 ± 0.75 |

| Parameter | Control | SS BW | CrPic BW | BW BW | BW BW | BW BW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omentum (g) | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.71 ± 0.08 * | 0.70 ± 0.02 * | 0.63 ± 0.04 * |

| Heart (g) | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 1.46 ± 0.19 | 1.51 ± 0.07 | 1.54 ± 0.09 | 1.45 ± 0.21 | 1.39 ± 0.18 |

| Lung (g) | 2.10 ± 0.61 | 1.69 ± 0.34 | 2.50 ± 0.76 | 2.05 ± 0.62 | 2.49 ± 0.70 | 1.92 ± 0.58 |

| Liver (g) | 13.30 ± 0.36 | 12.89 ± 1.11 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 11.87 ± 1.28 | 12.85 ± 2.06 | 11.39 ± 0.96 * |

| Kidney (g) | 2.51 ± 0.18 | 2.40 ± 0.24 | 2.53 ± 0.19 | 2.36 ± 0.37 | 2.56 ± 0.26 | 2.42 ± 0.20 |

| Adrenal gland (g) | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Pancreas (g) | 0.86 ± 0.17 | 1.08 ± 0.15 * | 1.09 ± 0.26 * | 1.10 ± 0.12 * | 1.09 ± 0.14 * | 1.26 ± 0.19 * |

| Spleen (g) | 0.95 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.10 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.05 |

| Prostate gland (g) | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.40 ± 0.10 |

| Seminal vesicle (g) | 1.61 ± 0.15 | 1.57 ± 0.33 | 1.53 ± 0.37 | 1.43 ± 0.31 | 1.40 ± 0.27 | 1.42 ± 0.07 |

| Epididymis (g) | 1.02 ± 0.28 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.09 | 1.18 ± 0.28 | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 1.06 ± 0.23 |

| Testis (g) | 2.21 ± 0.74 | 2.57 ± 0.60 | 2.62 ± 0.18 | 2.63 ± 0.26 | 2.74 ± 0.26 | 2.75 ± 0.89 |

| Parameter | Control | SS BW | CrPic BW | BW BW | BW BW | BW BW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 158.33 ± 17.06 | 155.33 ± 12.19 | 152.00 ± 8.00 | 152.50 ± 6.95 | 143.33 ± 6.00 * | 139.83 ± 15.88 * | |

| 23.33 ± 1.03 | 23.83 ± 1.17 | 21.83 ± 1.47 | 23.00 ± 1.55 | 23.33 ± 3.14 | 21.33 ± 3.67 | |

| 91.17 ± 3.92 | 85.17 ± 4.17 | 80.00 ± 8.37 * | 81.67 ± 9.33 * | 75.33 ± 3.88 * | 67.83 ± 8.16 * | |

| 38.00 ± 7.07 | 42.17 ± 3.66 | 42.83 ± 2.71 | 45.83 ± 5.81 * | 46.00 ± 2.83 * | 46.33 ± 6.62 * | |

| 35.17 ± 2.14 | 33.00 ± 2.28 | 18.17 ± 2.32 * | 19.00 ± 8.44 * | 15.00 ± 5.97 * | 13.17 ± 1.72 * | |

| 98.33 ± 38.52 | 82.67 ± 16.82 | 88.83 ± 53.92 | 70.83 ± 10.98 | 49.00 ± 7.56 * | 48.67 ± 12.39 * | |

| 5.63 ± 0.30 | 6.27 ± 0.16 * | 6.27 ± 0.22 * | 6.15 ± 0.29 * | 6.50 ± 0.30 * | 6.15 ± 0.39 * |

| Treatment | Kidney () | Liver () |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 95.75 ± 3.87 | 98.18 ± 6.33 |

| BW | 103.72 ± 24.35 | 99.67 ± 12.34 |

| BW | 104.93 ± 13.73 | 110.61 ± 16.23 |

| BW BW | 112.09 ± 21.65 | 107.88 ± 10.06 |

| BW BW | 132.18 ± 20.77 * | 114.93 ± 7.74 * |

| BW BW | 123.47 ± 13.06 * | 116.30 ± 8.56 * |

| Treatment | Size of Adipose Cell | |

|---|---|---|

| <50 µm (%) | >50 µm (%) | |

| Control | 0 | 6/6 (100) |

| BW | 1/6 (17) | 5/6 (83) |

| BW | 3/6 (50) * | 3/6 (50) * |

| BW | 5/6 (83) * | 1/6 (17) * |

| BW | 6/6 (100) * | 0 * |

| BW BW | 6/6 (100) * | 0 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tocharus, C.; Saelim, J.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Consumption of Sericin Enhances the Bioavailability and Metabolic Efficacy of Chromium Picolinate in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311505

Tocharus C, Saelim J, Sutheerawattananonda M. Consumption of Sericin Enhances the Bioavailability and Metabolic Efficacy of Chromium Picolinate in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311505

Chicago/Turabian StyleTocharus, Chainarong, Jiraphan Saelim, and Manote Sutheerawattananonda. 2025. "Consumption of Sericin Enhances the Bioavailability and Metabolic Efficacy of Chromium Picolinate in Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311505

APA StyleTocharus, C., Saelim, J., & Sutheerawattananonda, M. (2025). Consumption of Sericin Enhances the Bioavailability and Metabolic Efficacy of Chromium Picolinate in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311505