Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of Different Novel Steroid-Derived Nitrones and Oximes on Cerebral Ischemia In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

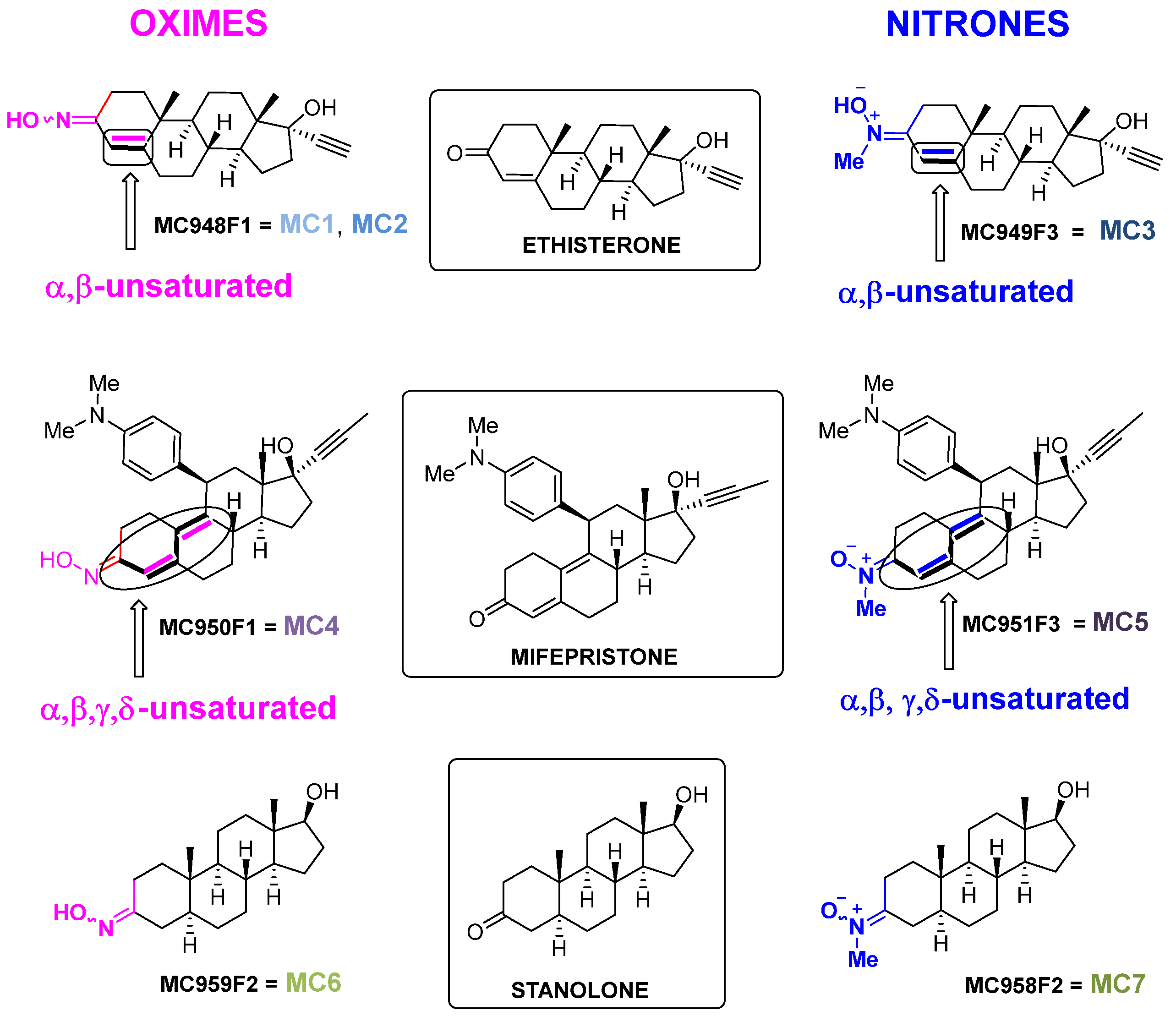

- (1)

- Ethisterone (Figure 1), also known as ethinyltestosterone, pregneninolone, and anhydrohydroxyprogesterone, is a synthetic progestogen (i.e., an agonist of the progesterone receptor) historically used as a progestin medication to treat gynecological disorders [47,48,49,50]. Although no longer in clinical use, ethisterone’s steroidal framework provided a valuable starting point for chemical modifications. From ethisterone, two oxime derivatives (MC948F1 = MC1, MC2) and one nitrone derivative (MC949F3 = MC3) were synthesized (group 1). All three are known compounds that have been prepared as previously described [51,52], showing analytical and spectroscopic data consistent with published values (see Supporting Information) [49,51,52]. Notably, the oxime derivatives exhibited distinct E/Z isomer ratios, with MC1 showing a 2:1 ratio and MC2 a 4:1 ratio.

- (2)

- Mifepristone (Figure 1), also known as RU-486, is an antiprogestogen (i.e., it blocks the effects of progesterone) widely recognized for its medical use in pregnancy termination and miscarriage management [53]. From mifepristone, one oxime derivative (MC950F1 = MC4) and one nitrone derivative (MC951F3 = MC5) were synthesized (group 2). While MC4 had been previously described [50], MC5 was synthesized here for the first time, with analytical and spectroscopic data confirming its structure (see Supporting Information).

- (3)

- Stanolone (Figure 1), also known as dihydrotestosterone (DHT), is an androgen and anabolic steroid used clinically to treat testosterone deficiency and other related conditions [54]. From stanolone, one oxime derivative (MC959F2 = MC6) [48,55] and one nitrone derivative (MC958F2 = MC7) were synthesized (group 3) [49]. Both compounds are known and were prepared as described in the literature, with analytical and spectroscopic data consistent with previously reported values (see Supporting Information) [48,49,55].

- (a)

- A single conjugated double bond associated with the oxime (or nitrone) moiety, as observed in the ethisterone derivatives (MC1, MC2, and MC3).

- (b)

- Two non-linear conjugated double bonds associated with the oxime (or nitrone) moiety, as observed in the mifepristone derivatives (MC4 and MC5).

- (c)

- The absence of conjugation in the oxime (or nitrone) moiety, as observed in the stanolone derivatives (MC6 and MC7).

2. Results

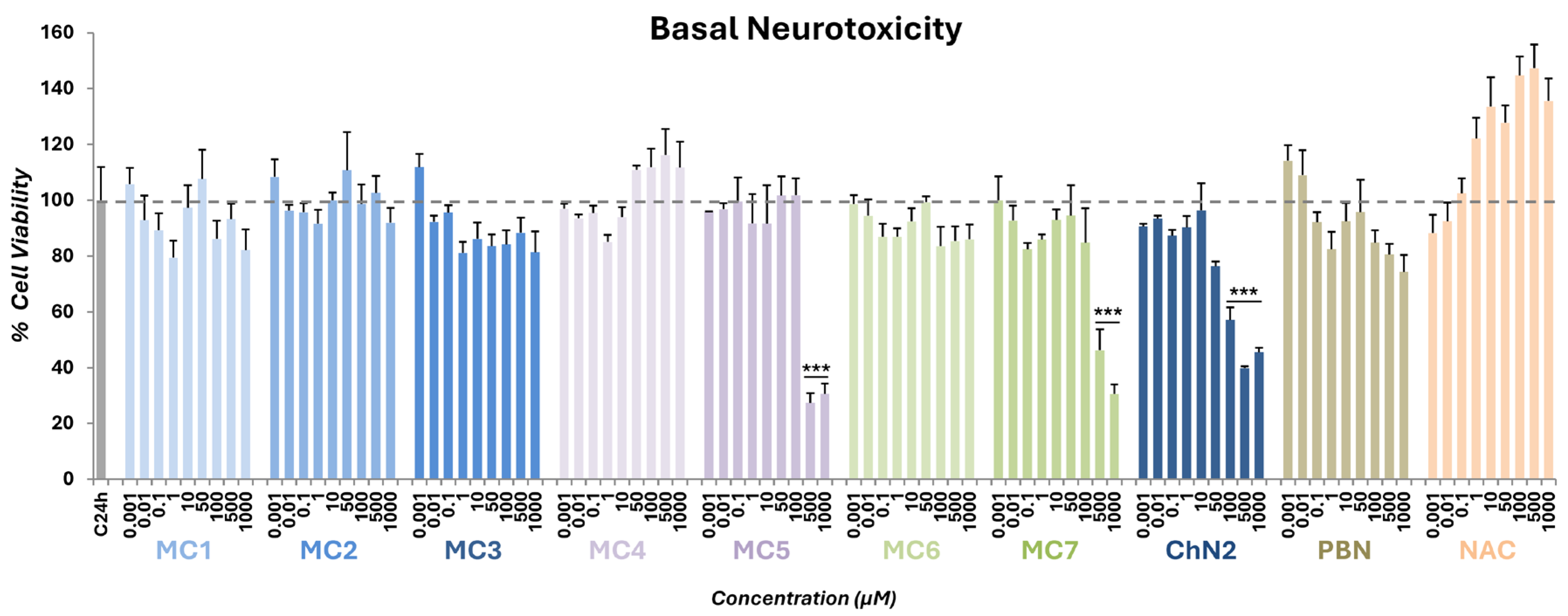

2.1. Basal Neurotoxicity of NSNs, NSOs, ChN2, PBN and NAC

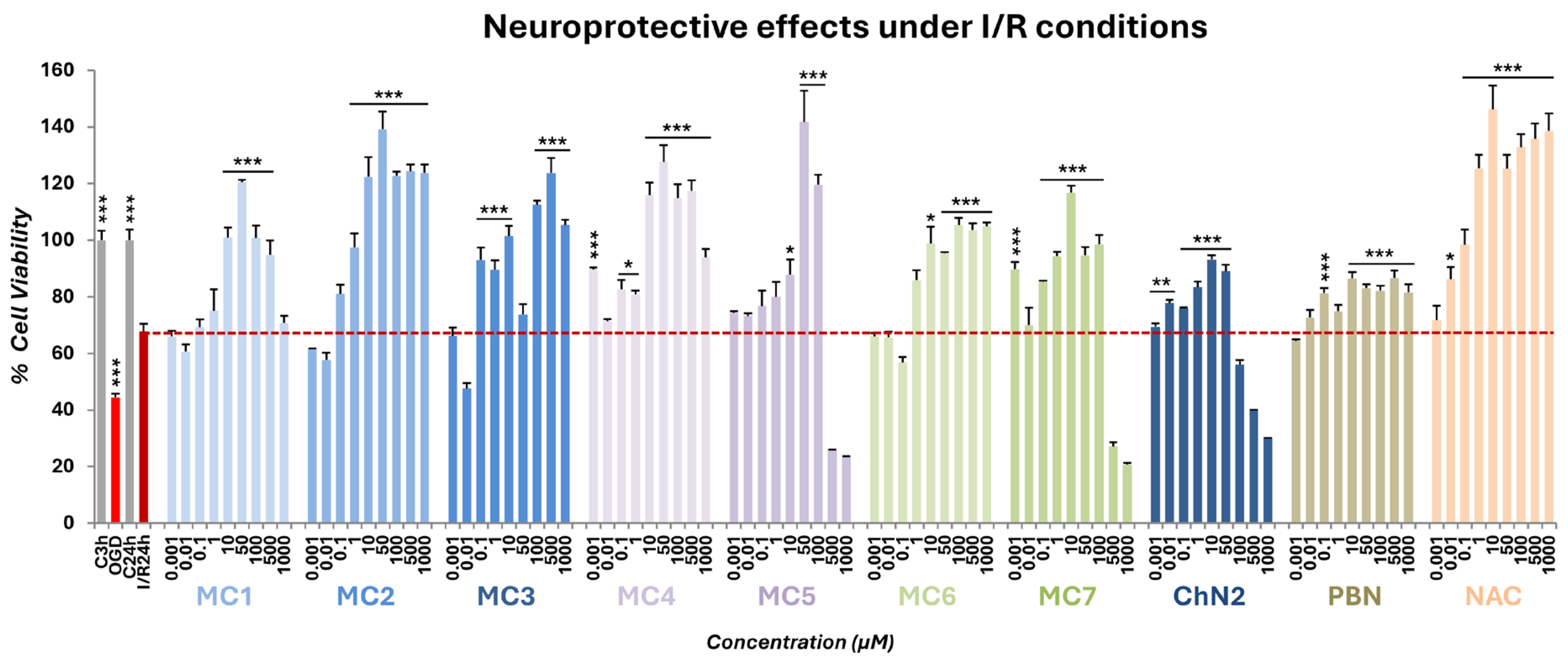

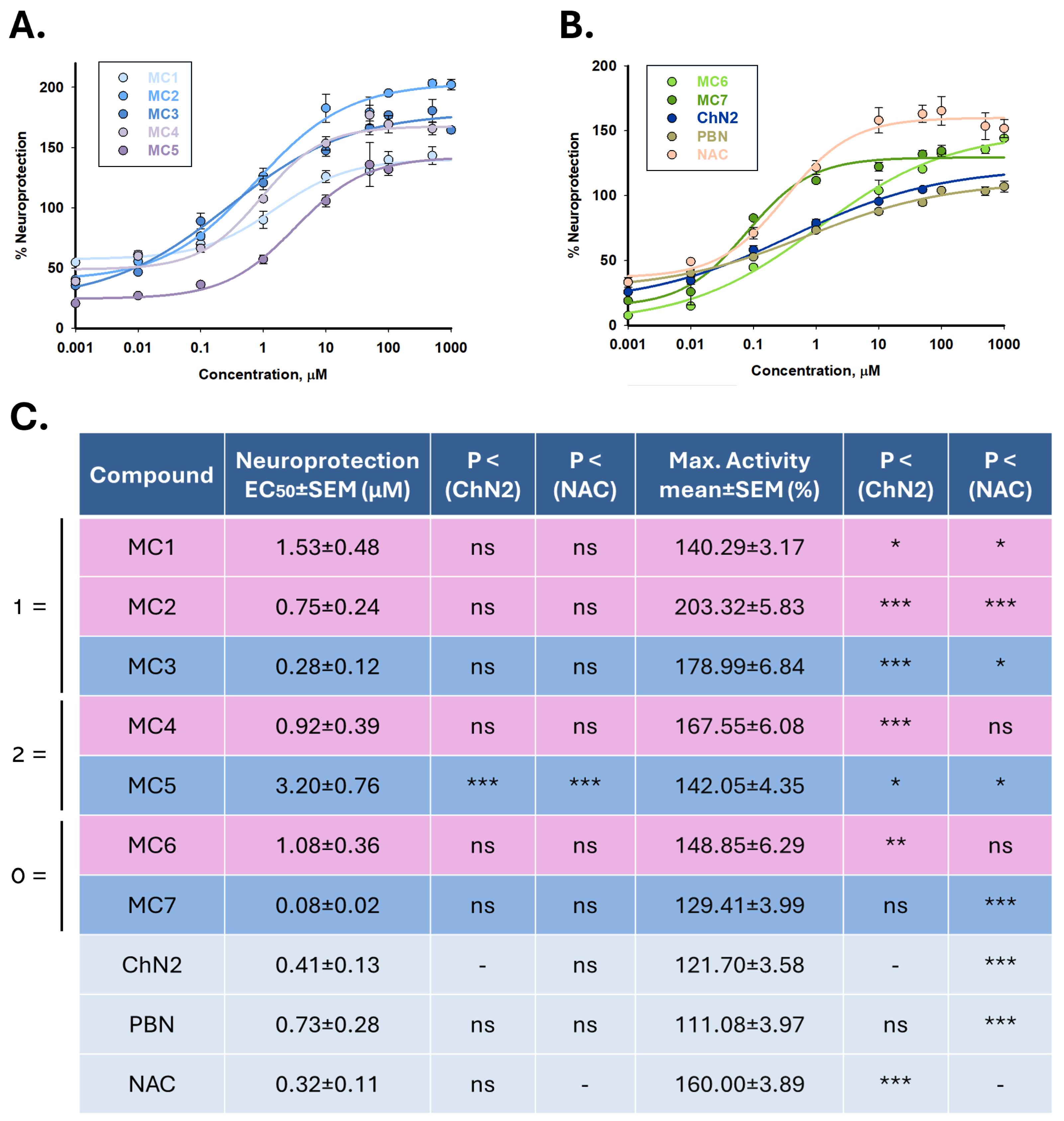

2.2. Neuroprotective Profiles of NSNs, NSOs, ChN2, PBN and NAC in a Cellular Model of Cerebral Ischemia

2.2.1. Effect on Cell Viability

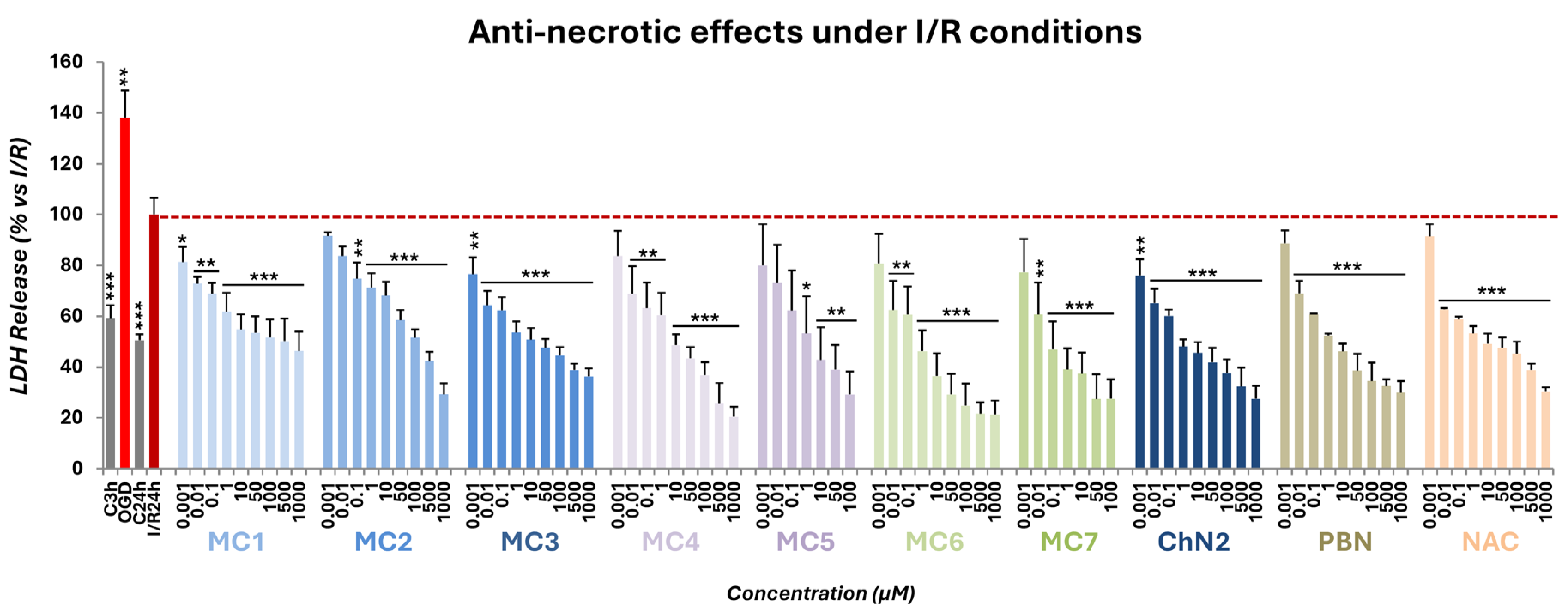

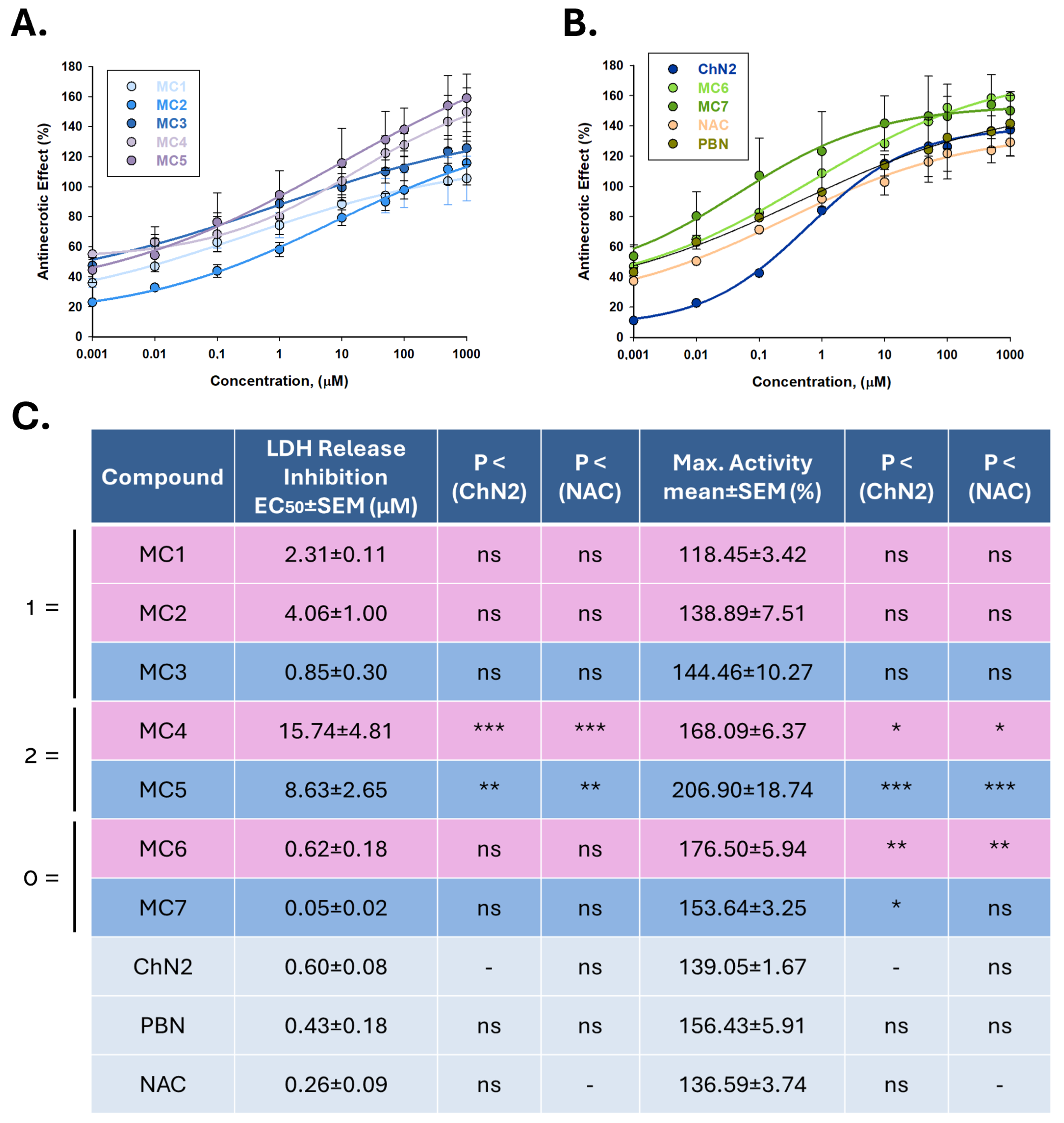

2.2.2. Effects on Necrotic Cell Death

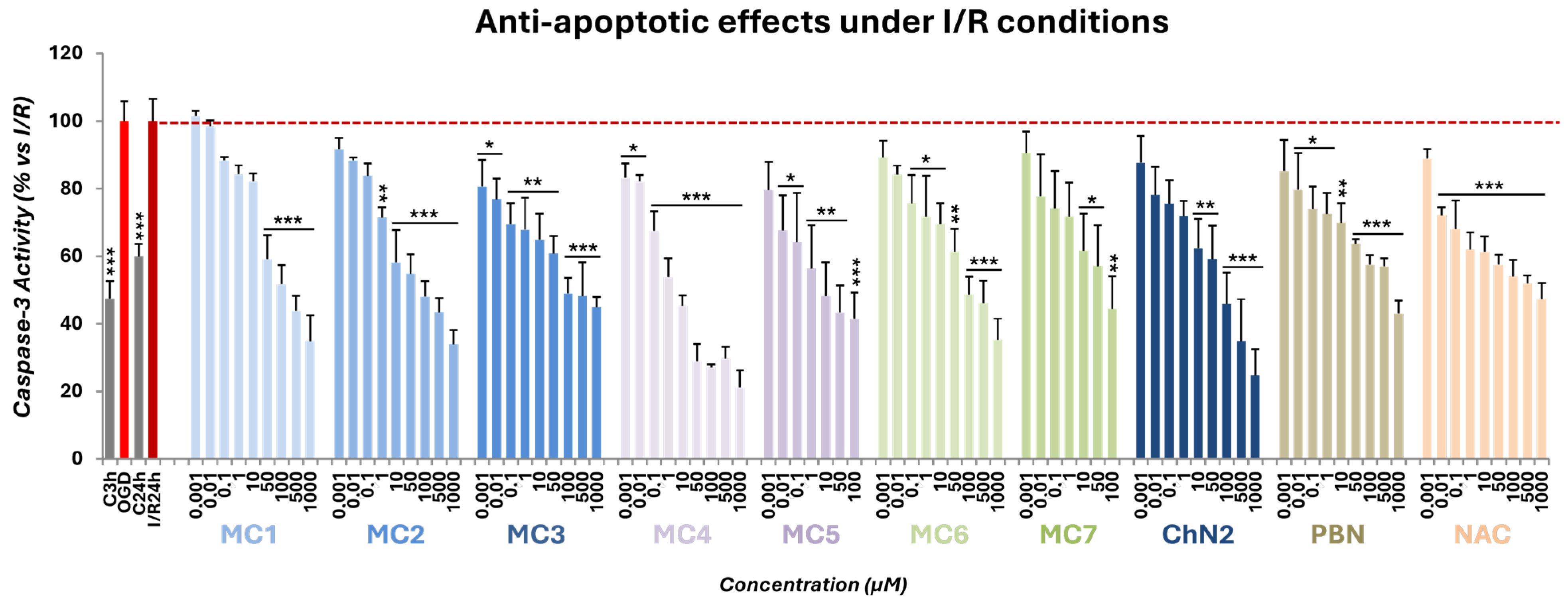

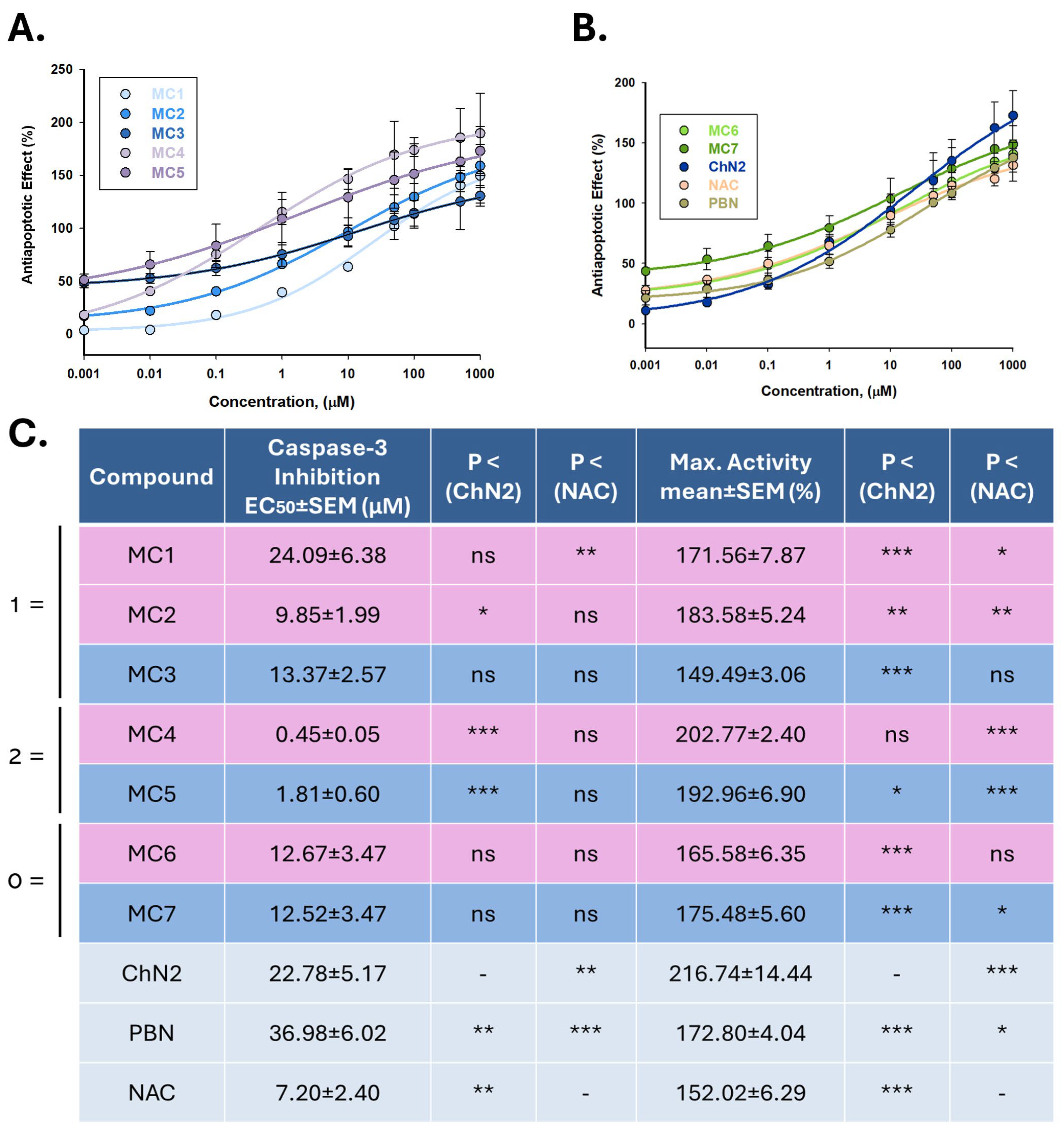

2.2.3. Effects on Apoptotic Cell Death

2.3. Antioxidant Profiles of NSNs, NSOs, ChN2, PBN and NAC

2.3.1. Cell-Free Antioxidant Assays

Estimation of Lipophilicity (ClogP)

Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation (ILPO)

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging

ABTS•+ Decolorization Assay

In Vitro Inhibition of Soybean LOX

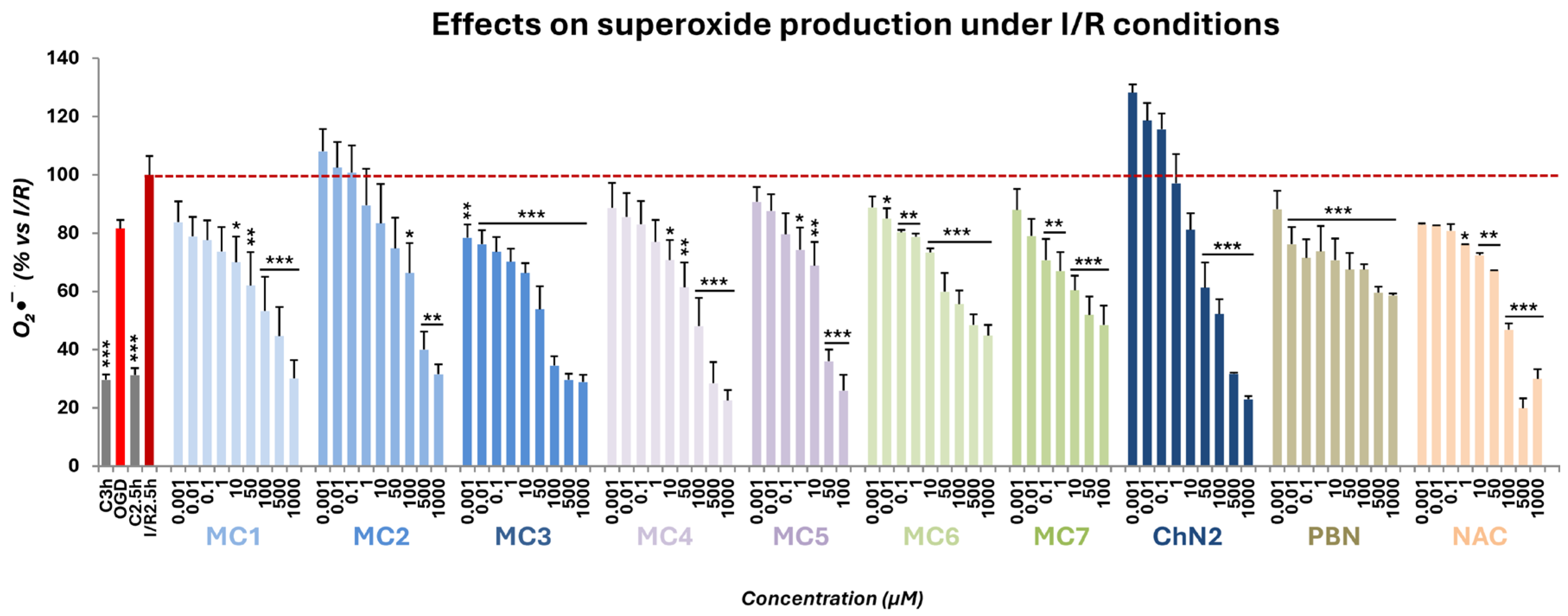

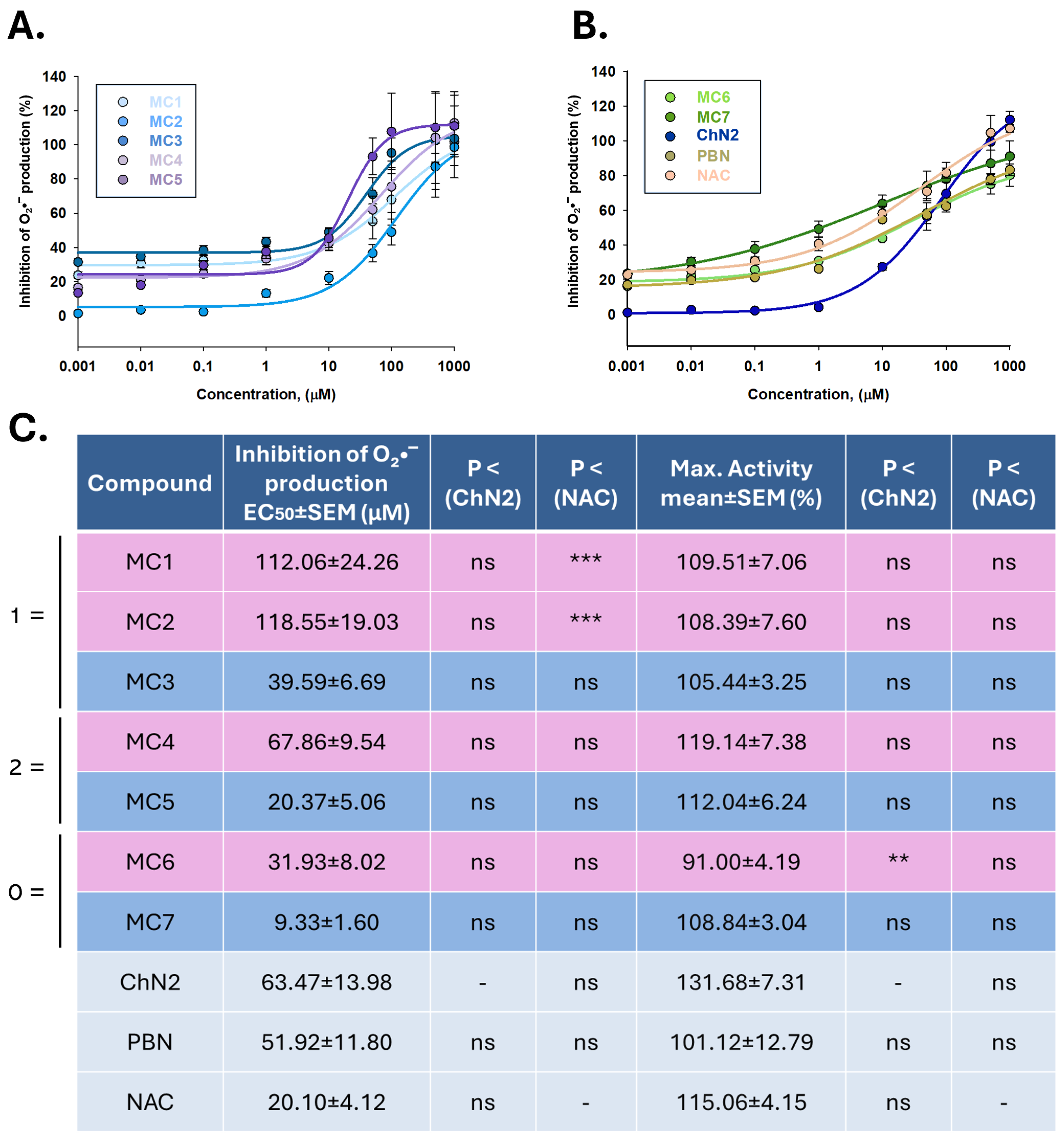

2.3.2. Superoxide Radical Scavenging in a Cellular Model of Cerebral Ischemia

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.2. Cell-Free Assays

4.2.1. Estimation of Lipophilicity (ClogP)

4.2.2. Determination of Reducing Activity (RA)

4.2.3. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition Assay

4.2.4. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Assay

4.2.5. ABTS•+ Decolorization Assay

4.2.6. Soybean LOX Inhibition Assay

4.3. Cellular Model of Cerebral Ischemia

4.3.1. Neuroblastoma Cell Cultures

4.3.2. Exposure of Neuroblastoma Cell Cultures to Oxygen–Glucose Deprivation (OGD)

4.4. Neuroprotection Assays

4.4.1. Evaluation of Cell Viability

4.4.2. Assessment of LDH Activity

4.4.3. Measurement of Caspase-3 Activity

4.5. Antioxidant Assays

Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species Formation

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Mato, M.; López-Arias, E.; Bugallo-Casal, A.; Correa-Paz, C.; Arias, S.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; Santamaría-Cadavid, M.; Campos, F. New Perspectives in Neuroprotection for Ischemic Stroke. Neuroscience 2024, 550, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; A Stark, B.; Johnson, C.O.; A Roth, G.; Bisignano, C.; Abady, G.G.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abedi, V.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Stroke and its Risk Factors, 1990-2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, R.; Fernández-Gajardo, R.; Gutiérrez, R.; Matamala, J.M.; Carrasco, R.; Miranda-Merchak, A.; Feuerhake, W. Oxidative Stress and Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke: Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2013, 12, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Candelario-Jalil, E. Emerging Neuroprotective Strategies for the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke: An Overview of Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 335, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnan, G.A.; Fisher, M.; Macleod, M.; Davis, S.M. Stroke. Lancet 2008, 371, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, Q.; Zhang, S.; Lei, P. Mechanisms of Neuronal Cell Death in Ischemic Stroke and their Therapeutic Implications. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 259–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, M.A.; Lo, E.H.; Iadecola, C. The Science of Stroke: Mechanisms in Search of Treatments. Neuron 2010, 67, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Yang, S.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Chen, M.; Tian, D.; Wang, W. Signaling Pathways Involved in Ischemic Stroke: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 215, Erratum in: Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; He, Y.; Chen, S.; Qi, S.; Shen, J. Therapeutic Targets of Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Ischemic Stroke: Applications for Natural Product Efficacy with Omics and Systemic Biology. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, M.; Gerner, S.T.; Bähr, M.; Doeppner, T.R. Neuroprotective Strategies for Ischemic Stroke-Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, P. Small Molecules as Modulators of Regulated Cell Death Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 2067–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurford, R.; Sekhar, A.; Hughes, T.A.T.; Muir, K.W. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Ischaemic Stroke. Pract. Neurol. 2020, 20, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenka, L.; Uppugunduri Satyanarayana, C.R.; George, M. Neuroprotective Agents in Acute Ischemic Stroke-A Reality Check. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seillier, C.; Lesept, F.; Toutirais, O.; Potzeha, F.; Blanc, M.; Vivien, D. Targeting NMDA Receptors at the Neurovascular Unit: Past and Future Treatments for Central Nervous System Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, E.; Sykes, G.; Falcione, S.; Munsterman, D.; Joy, T.; Kamtchum-Tatuene, J.; Jickling, G.C. Hemorrhagic Transformation in Ischemic Stroke and the Role of Inflammation. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 661955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochhead, J.J.; Ronaldson, P.T.; Davis, T.P. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption during Ischemic Stroke: Antioxidants in Clinical Trials. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 228, 116186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, S.I.; Baron, J.; Fisher, M. Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable X: Brain Cytoprotection Therapies in the Reperfusion Era. Stroke 2019, 50, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyden, P.; Buchan, A.; Boltze, J.; Fisher, M. Top Priorities for Cerebroprotective Studies-A Paradigm Shift: Report from STAIR XI. Stroke 2021, 52, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackensen, G.B.; Patel, M.; Sheng, H.; Calvi, C.L.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Day, B.J.; Liang, L.P.; Fridovich, I.; Crapo, J.D.; Pearlstein, R.D.; et al. Neuroprotection from delayed postischemic administration of a metalloporphyrin catalytic antioxidant. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 4582–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Duan, W.; Du, L.; Chu, D.; Wang, P.; Yang, Z.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Spasojevic, I.; et al. Intracarotid Infusion of Redox-Active Manganese Porphyrin, MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+, following Reperfusion Improves Long-Term, 28-Day Post-Stroke Outcomes in Rats. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Tovmasyan, A.; Sheng, H.; Xu, B.; Sampaio, R.S.; Reboucas, J.S.; Warner, D.S.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Spasojevic, I. Fe porphyrin-based SOD mimic and redox-active compound, (OH)FeTnHex-2-PyP4+, in a rodent ischemic stroke (MCAO) model: Efficacy and pharmacokinetics as compared to its Mn analogue, (H2O)MnTnHex-2-PyP. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselin, M.; Poeggeler, B.; Durand, G. Nitrone Derivatives as Therapeutics: From Chemical Modification to Specific-Targeting. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 2006–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.A.; Minnerup, J.; Balami, J.S.; Arba, F.; Buchan, A.M.; Kleinschnitz, C. Neuroprotection for Ischaemic Stroke: Translation from the Bench to the Bedside. Int. J. Stroke 2012, 7, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikov, M.B.; Chernysheva, G.A.; Smol’yakova, V.I.; Aliev, O.I.; Anishchenko, A.M.; Ulyakhina, O.A.; Trofimova, E.S.; Ligacheva, A.A.; Anfinogenova, N.D.; Osipenko, A.N.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Tryptanthrin-6-Oxime in a Rat Model of Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikov, M.B.; Chernysheva, G.A.; Aliev, O.I.; Smol’iakova, V.I.; Fomina, T.I.; Osipenko, A.N.; Rydchenko, V.S.; Anfinogenova, Y.J.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Schepetkin, I.A.; et al. Protective Effects of a New C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Inhibitor in the Model of Global Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Molecules 2019, 24, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov, M.B.; Chernysheva, G.A.; Smolyakova, V.I.; Aliev, O.I.; Trofimova, E.S.; Sherstoboev, E.Y.; Osipenko, A.N.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Anfinogenova, Y.J.; Schepetkin, I.A.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of a Novel Inhibitor of C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase in the Rat Model of Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Cells 2020, 9, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuan, C.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Yang, D.D.; Liao, G.; Schloemer, A.J.; Dong, C.; Bao, J.; Banasiak, K.J.; Haddad, G.G.; Flavell, R.A.; et al. A Critical Role of Neural-Specific JNK3 for Ischemic Apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15184–15189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ghosh, S. Putative Roles of Mitochondrial Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel, Bcl-2 Family Proteins and C-Jun N-Terminal Kinases in Ischemic Stroke Associated Apoptosis. Biochim. Open 2017, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atochin, D.N.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Seledtsov, V.I.; Swanson, H.; Quinn, M.T.; Huang, P.L. A Novel Dual NO-Donating Oxime and C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Inhibitor Protects Against Cerebral Ischemia–reperfusion Injury in Mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 618, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Dai, Q.; Han, K.; Hong, W.; Jia, D.; Mo, Y.; Lv, Y.; Tang, H.; Fu, H.; Geng, W. JNK-IN-8, a C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Inhibitor, Improves Functional Recovery through Suppressing Neuroinflammation in Ischemic Stroke. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benakis, C.; Bonny, C.; Hirt, L. JNK Inhibition and Inflammation After Cerebral Ischemia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010, 24, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Bansal, R. Revisiting the Role of Steroidal Therapeutics in the 21st Century: An Update on FDA Approved Steroidal Drugs (2000–2024). RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; Simoncini, T.; Yang, Z.; Limbourg, F.P.; Plumier, J.C.; Rebsamen, M.C.; Hsieh, C.M.; Chui, D.S.; Thomas, K.L.; Prorock, A.J.; et al. Acute Cardiovascular Protective Effects of Corticosteroids are Mediated by Non-Transcriptional Activation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi-Buisson, N.; Villanueva, V.; Bulteau, C.; Delalande, O.; Dulac, O.; Chiron, C.; Nabbout, R. Long Term Response to Steroid Therapy in Rasmussen Encephalitis. Seizure 2007, 16, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidinia, Z.; Karimian, M.; Joghataei, M.T. Neurosteroids and their Receptors in Ischemic Stroke: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 160, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, X.; Lou, J.; Luo, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, X.; et al. Neurosteroids: A Novel Promise for the Treatment of Stroke and Post-stroke Complications. J. Neurochem. 2021, 160, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; Mcnamee, C.; et al. Drug Repurposing: Progress, Challenges and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.; Guerra, B.; Alonso, R.; Ramírez, C.M.; Díaz, M. Estrogen Activates Classical and Alternative Mechanisms to Orchestrate Neuroprotection. Curr. Neurovasc Res. 2005, 2, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Azcoitia, I.; DonCarlos, L.L. Neuroprotection by Estradiol. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001, 63, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbruzzese, G.; Morón-Oset, J.; Díaz-Castroverde, S.; García-Font, N.; Roncero, C.; López-Muñoz, F.; Marco Contelles, J.L.; Oset-Gasque, M.J. Neuroprotection by Phytoestrogens in the Model of Deprivation and Resupply of Oxygen and Glucose in Vitro: The Contribution of Autophagy and Related Signaling Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Le, Q.; Goodyer, C.; Gelfand, M.; Trifiro, M.; LeBlanc, A. Testosterone-Mediated Neuroprotection through the Androgen Receptor in Human Primary Neurons. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, M.I.; Chioua, M.; Martínez-Alonso, E.; Soriano, E.; Montaner, J.; Masjuán, J.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.J.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Alcázar, A. CholesteroNitrones for Stroke. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Alonso, E.; Escobar-Peso, A.; Ayuso, M.I.; Gonzalo-Gobernado, R.; Chioua, M.; Montoya, J.J.; Montaner, J.; Fernández, I.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Alcázar, A. Characterization of a CholesteroNitrone (ISQ-201), a Novel Drug Candidate for the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, B.; Izquierdo-Bermejo, S.; Martín-De-Saavedra, M.D.; López-Muñoz, F.; Chioua, M.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Oset-Gasque, M.J. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of CholesteroNitrone ChN2 and QuinolylNitrone QN23 in an Experimental Model of Cerebral Ischemia: Involvement of Necrotic and Apoptotic Cell Death. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolić, D.; Šinko, G.; Jean, L.; Chioua, M.; Dias, J.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Kovarik, Z. Cholesterol Oxime Olesoxime Assessed as a Potential Ligand of Human Cholinesterases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.J.; Clemensson, L.E.; Schiöth, H.B.; Nguyen, H.P. Olesoxime in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Scrutinising a Promising Drug Candidate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 168, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcrobb, L.; Handelsman, D.J.; Kazlauskas, R.; Wilkinson, S.; Mcleod, M.D.; Heather, A.K. Structure–activity Relationships of Synthetic Progestins in a Yeast-Based in Vitro Androgen Bioassay. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 110, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camoutsis, C.; Catsoulacos, P. Formation of Bishomoazasteroids by the Beckmann Rearrangement. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1988, 25, 1617–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, P.M.; Tiernan, P. Steroidal Nitrones. J. Org. Chem. 1974, 39, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, V.; Teutsch, J.G.; Philibert, D. Preparation of Estradienolone Derivatives Useful as Antiglucocorticoids and Antiprogestomimetics, and Their Pharmaceutical Formulation. U.S. Patent US 1985-693682, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, G. Compounds for Targeted Therapies of Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer. U.S. Patent Application No. 17/434,672, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Matlin, S.A.; Jiang, L.; Roshdy, S.; Zhou, R. Resolution and Identification of Steroid Oxime Syn and Antiisomers by HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 1990, 13, 3455–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadepond, F.; Ulmann, A.; Baulieu, E. RU486 (MIFEPRISTONE): Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Uses. Annu. Rev. Med. 1997, 48, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, W. Anabolics; Molecular Nutrition LLC: Jupiter, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, K.; Hara, S. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra on Syn and Anti Isomers of Steroidal 3-Ketoximes. Chem. Ind. 1968, 27, 911–912. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W.; Zhang, X.X.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.Y. Protective effects of N-acetylcysteine on oxygen-glucose deprivation injured cortical astrocytes in rats. J. Shandong Univ. Health Sci. 2008, 46, 859–862. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlas, N.; Małecki, A. Neuroprotective effect of N-acetylcysteine in neurons exposed to arachidonic acid during simulated ischemia in vitro. Pharmacol. Rep. 2009, 61, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Qin, Y.; Li, D.; Cai, N.; Wu, J.; Jiang, L.; Jie, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, H. Inhibition of PDE4 protects neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress through activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, B.; Sekhon, C.; Khan, M.; Patel, S.J.; Singh, I.; Singh, A.K. N-Acetyl cysteine protects against injury in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2003, 971, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Sekhon, B.; Jatana, M.; Giri, S.; Gilg, A.G.; Sekhon, C.; Singh, I.; Singh, A.K. Administration of N-acetylcysteine after focal cerebral ischemia protects brain and reduces inflammation in a rat model of experimental stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 76, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniei, H.; Shirpoor, A.; Naderi, R. Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Induced Neuronal Damage, Inflammation, miR-374a-5p, MAPK6, NLRP3, and Smad6 Alterations: Rescue Effect of N-acetylcysteine. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 30, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetghadam, M.; Mazdeh, M.; Abolfathi, P.; Mohammadi, Y.; Mehrpooya, M. Evidence for a Beneficial Effect of Oral N-acetylcysteine on Functional Outcomes and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.D.; Moss, H.G.; Brown, T.R.; Yazdani, M.; Thayyil, S.; Montaldo, P.; Vento, M.; Kuligowski, J.; Wagner, C.; Hollis, B.W.; et al. NAC and Vitamin D Improve CNS and Plasma Oxidative Stress in Neonatal HIE and Are Associated with Favorable Long-Term Outcomes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.K.; Moriwaki, K.; De Rosa, M.J. Detection of Necrosis by Release of Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 979, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.G.; Jänicke, R.U. Emerging Roles of Caspase-3 in Apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, I.I.; van Beek, T.A.; Linssen, J.P.H.; de Groot, A.; Evstatieva, L.N. Screening of Plant Extracts for Antioxidant Activity: A Comparative Study on Three Testing Methods. Phytochem. Anal. 2002, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liégeois, C.; Lermusieau, G.; Collin, S. Measuring Antioxidant Efficiency of Wort, Malt, and Hops Against the 2,2‘-Azobis(2-Amidinopropane) Dihydrochloride-Induced Oxidation of an Aqueous Dispersion of Linoleic Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B. Hydroxyl Radical and its Scavengers in Health and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2011, 2011, 809696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brash, A.R. Lipoxygenases: Occurrence, Functions, Catalysis, and Acquisition of Substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23679–23682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådmark, O.; Samuelsson, B. 5-Lipoxygenase: Mechanisms of Regulation. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Funk, C.D. Lipoxygenase Pathways in Atherogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2004, 14, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shureiqi, I.; Lippman, S.M. Lipoxygenase Modulation to Reverse Carcinogenesis 1. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 6307–6312. [Google Scholar]

- Pontiki, E.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Litinas, K.; Geromichalos, G. Novel Cinnamic Acid Derivatives as Antioxidant and Anticancer Agents: Design, Synthesis and Modeling Studies. Molecules 2014, 19, 9655–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindokas, V.P.; Jordbn, J.; Lee, C.C.; Miller, R.J. Superoxide Production in Rat Hippocampal Neurons: Selective Imaging with Hydroethidine. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1324–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, P.M.; Gavins, F.N.E. Modeling Ischemic Stroke in Vitro: Status Quo and Future Perspectives. Stroke 2016, 47, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradillo, J.M.; García-Culebras, A.; Cuartero, M.I.; Peña-Martínez, C.; Moro, M.Á.; Lizasoain, I.; Moraga, A. Del Laboratorio a La Clínica En El Ictus Isquémico Agudo. Modelos Experimentales in Vitro E in Vivo. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 75, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Nicol, C.J.B.; Cheng, Y.; Yen, C.; Wang, Y.; Chiang, M. Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol Against Oxygen Glucose Deprivation Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction by Activation of AMPK in SH-SY5Y Cells with 3D Gelatin Scaffold. Brain Res. 2020, 1726, 146492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Hu, L.; Li, G. SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line: In Vitro Cell Model of Dopaminergic Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease. Chin. Med. J. 2010, 123, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, B.; Izquierdo-Bermejo, S.; Serrano, J.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Chioua, M.; López-Muñoz, F.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Martínez-Murillo, R.; Oset-Gasque, M.J. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of New Quinolylnitrones in in Vitro and in Vivo Cerebral Ischemia Models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCully, J.D.; Wakiyama, H.; Hsieh, Y.; Jones, M.; Levitsky, S. Differential Contribution of Necrosis and Apoptosis in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, M.G.; Xu, D.; Amin, P.; Lee, J.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Kelliher, M.; Pasparakis, M.; Yuan, J. Sequential Activation of Necroptosis and Apoptosis Cooperates to Mediate Vascular and Neural Pathology in Stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 4959–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapski, G.A.; Czubowicz, K.; Strosznajder, R.P. Evaluation of the Antioxidative Properties of Lipoxygenase Inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rep. 2012, 64, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Bermejo, S.; Chamorro, B.; Martín-de-Saavedra, M.D.; Lobete, M.; López-Muñoz, F.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Oset-Gasque, M.J. In Vitro Modulation of Autophagy by New Antioxidant Nitrones as a Potential Therapeutic Approach for the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro, B.; Diez-Iriepa, D.; Merás-Sáiz, B.; Chioua, M.; García-Vieira, D.; Iriepa, I.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; López-Muñoz, F.; Martínez-Murillo, R.; González-Nieto, D.; et al. Synthesis, Antioxidant Properties and Neuroprotection of A-Phenyl-Tert-Butylnitrone Derived HomoBisNitrones in in Vitro and in Vivo Ischemia Models. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds a/Standards a | ClogP b | ILPO (%) | LOX Inhibition (% or IC50) (μM) | •OH Scav. Activity (%) | ABTS+● (%) | DPPH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC1 (O) | 3.39 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 1.0% | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| MC2 (O) | 3.39 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 97.0 ± 1.5 μM | 57.0 ± 1.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.1 |

| MC3 (N) | 3.82 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 62.0 ± 0.8 μM | 74.2 ± 1.9 | n.a. | 12.0 ± 0.8 |

| MC4 (O) | 6.10 | n.a. | 3.8 ± 0.3 μM | 99.0 ± 1.8 | 13.0 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 1.0 |

| MC5 (N) | 5.50 | 19 ± 1.1 | n.a | 77.3 ± 2.1 | 12.6 ± 0.6 | 11.0 ± 0.3 |

| MC6 (O) | 3.88 | n.a | n.a | 95.0 ± 2.7 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 36.0 ± 1.2 |

| MC7 (N) | 4.06 | 13 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.7% | 51.5 ± 1.7 | 40.5 ± 1.6 | 18.6 ± 0.7 |

| NDGA | 3.92 | n.d. | 0.5 ± 0.1% | n.d. | n.d. | 96.0 ± 2.3 |

| Trolox | 3.09 | 93 ± 1.9 | n.d. | 88.0 ± 2.2 | 91.0 ± 2.0 | n.d. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izquierdo-Bermejo, S.; Chioua, M.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; López-Muñoz, F.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Oset-Gasque, M.J. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of Different Novel Steroid-Derived Nitrones and Oximes on Cerebral Ischemia In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311506

Izquierdo-Bermejo S, Chioua M, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, López-Muñoz F, Marco-Contelles J, Oset-Gasque MJ. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of Different Novel Steroid-Derived Nitrones and Oximes on Cerebral Ischemia In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311506

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzquierdo-Bermejo, Sara, Mourad Chioua, Dimitra Hadjipavlou-Litina, Francisco López-Muñoz, José Marco-Contelles, and María Jesús Oset-Gasque. 2025. "Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of Different Novel Steroid-Derived Nitrones and Oximes on Cerebral Ischemia In Vitro" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311506

APA StyleIzquierdo-Bermejo, S., Chioua, M., Hadjipavlou-Litina, D., López-Muñoz, F., Marco-Contelles, J., & Oset-Gasque, M. J. (2025). Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Properties of Different Novel Steroid-Derived Nitrones and Oximes on Cerebral Ischemia In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311506