MicroRNA-210 Suppresses NF-κB Signaling in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Dental Pulp Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions

Abstract

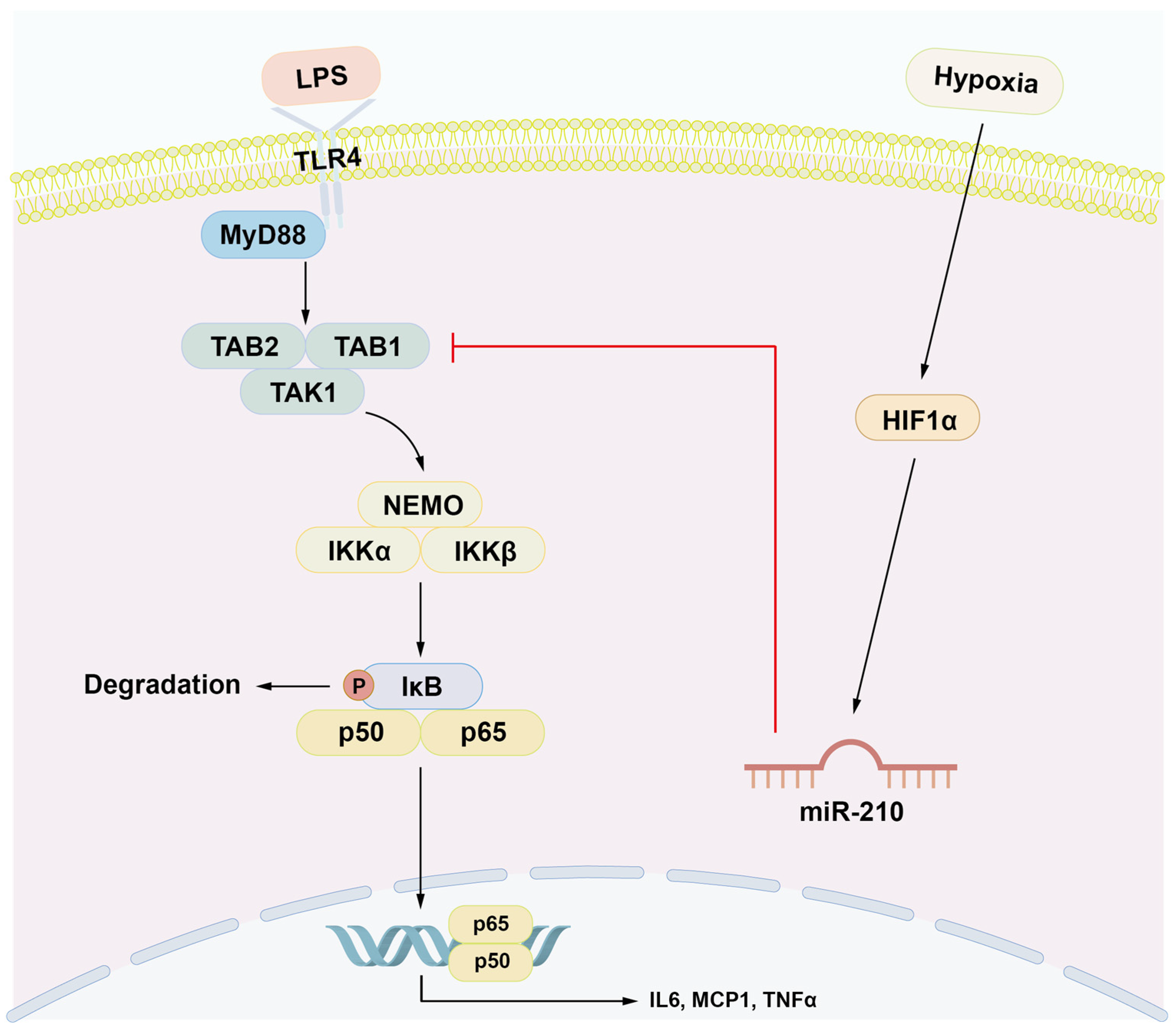

1. Introduction

2. Results

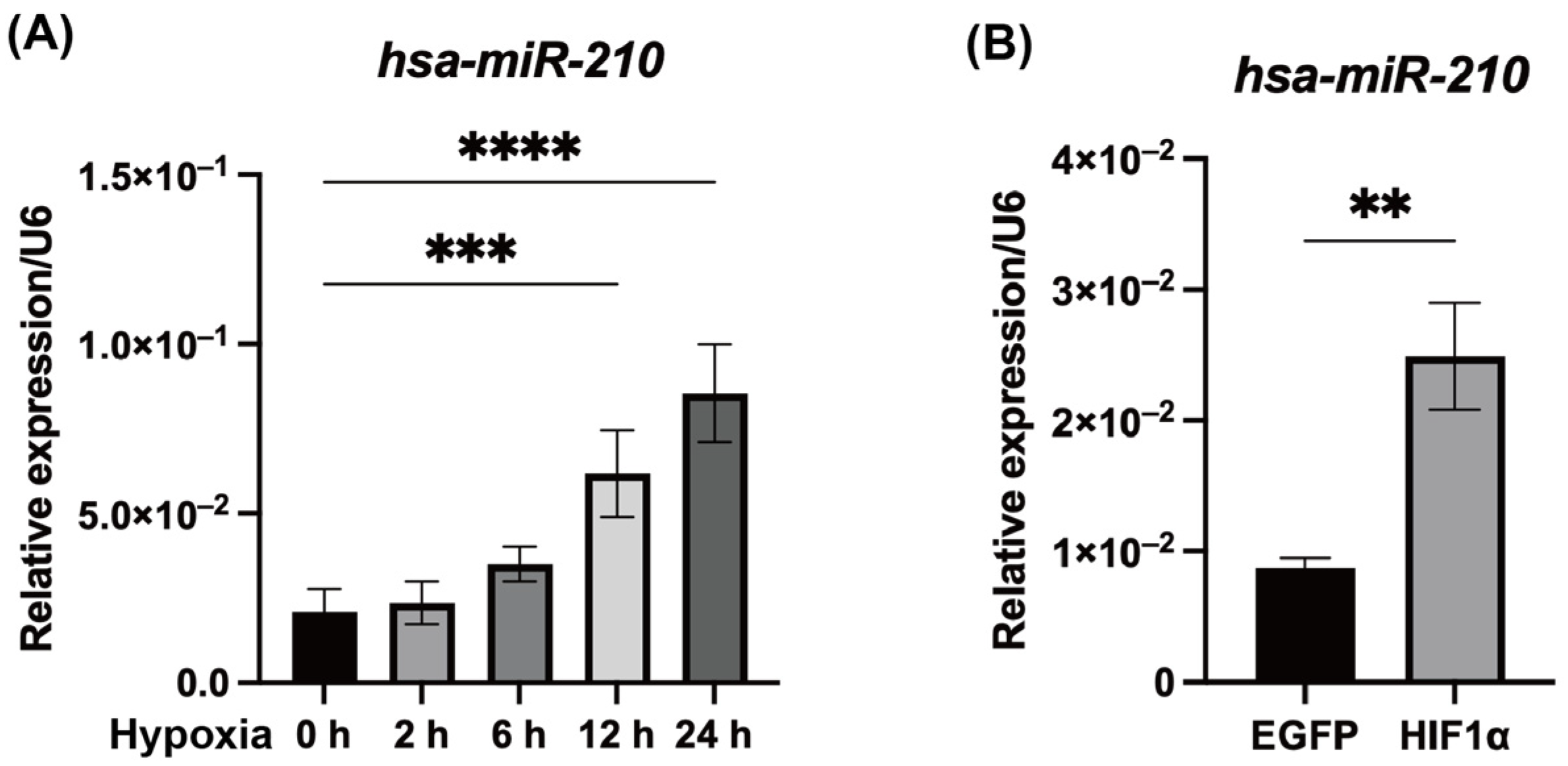

2.1. Hypoxic Conditions and HIF1α Overexpression Promoted miR-210 Expression in hDPCs

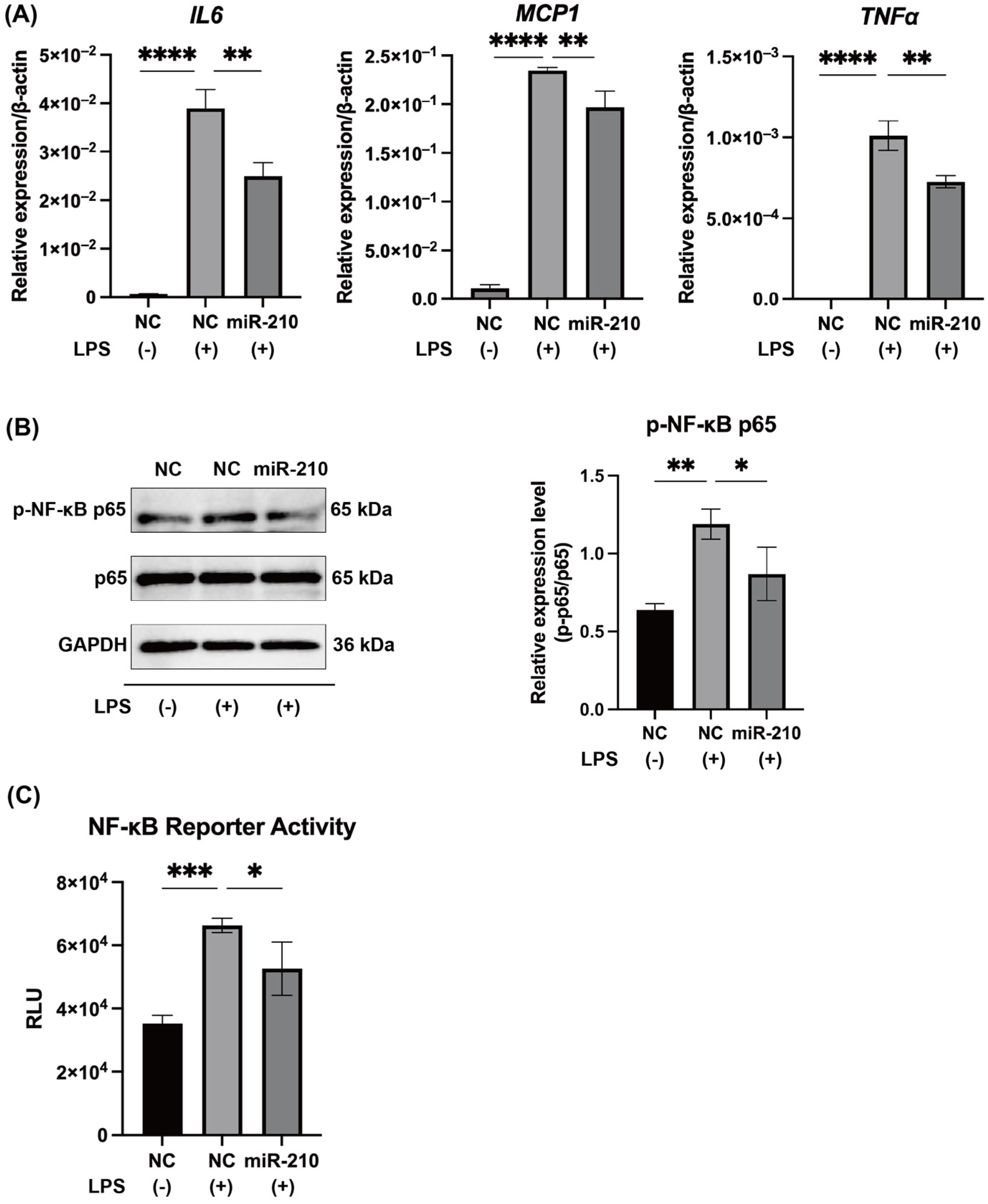

2.2. MiR-210 Downregulated the Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and the NF-κB Signaling in LPS-Stimulated hDPCs

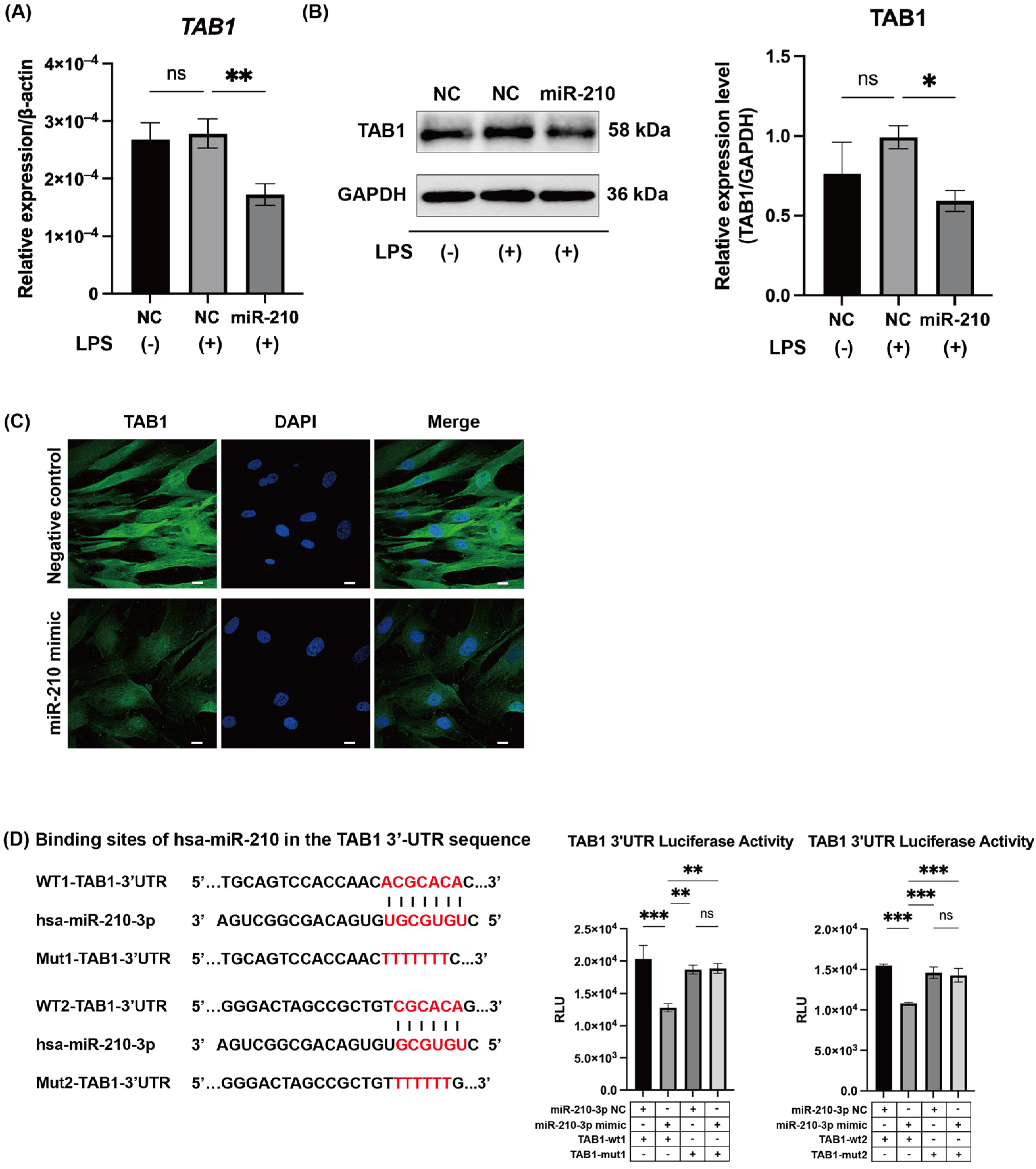

2.3. MiR-210 Targeted TAB1 in NF-κB Signaling

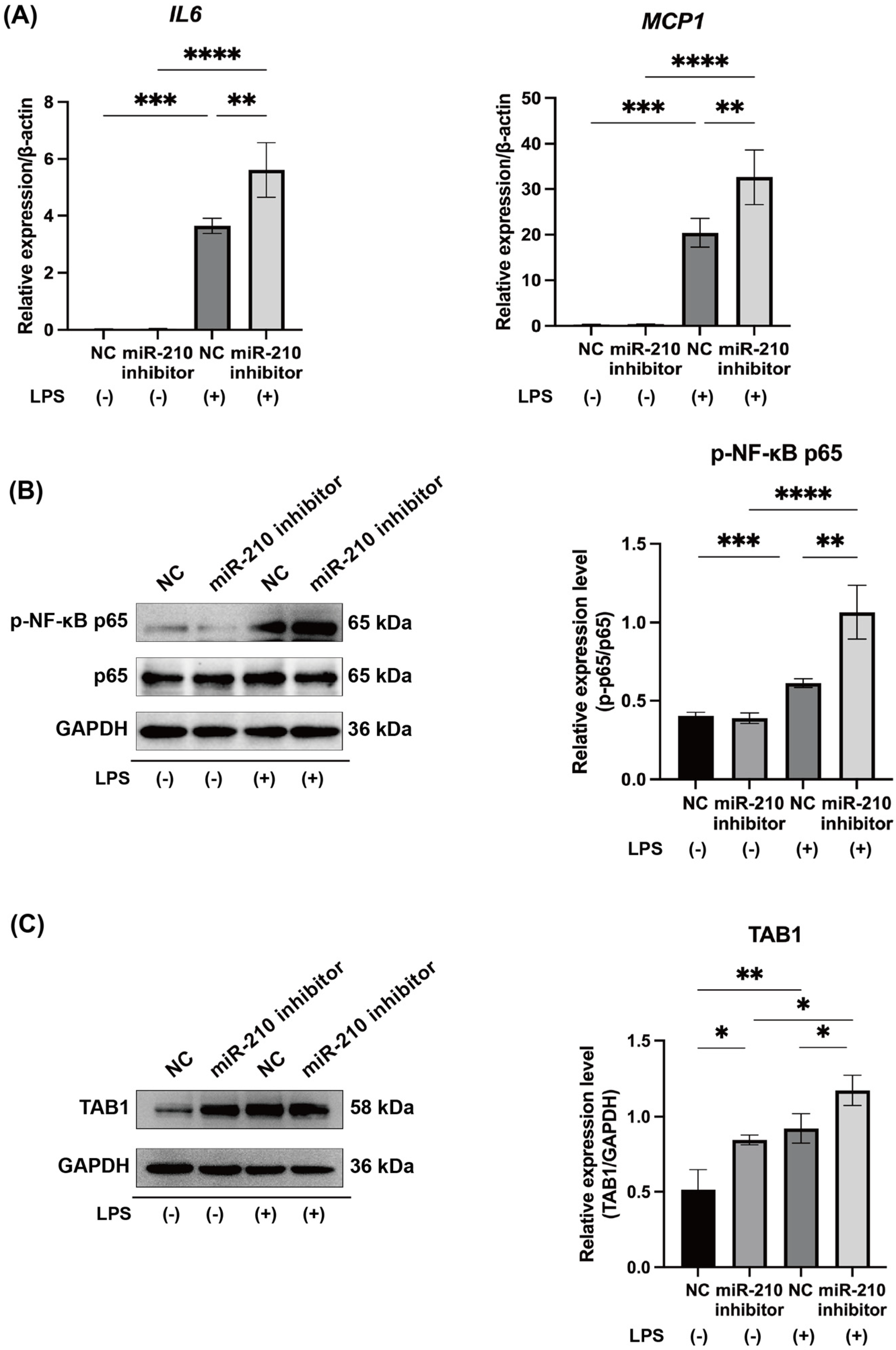

2.4. MiR-210 Inhibitor Upregulated the Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and NF-κB Signaling in LPS-Stimulated hDPCs

2.5. MiR-210 Downregulated the Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and the NF-κB Signaling in LPS-Stimulated Rat Pulp Tissue Ex Vivo

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. miRNA Array

4.3. MiR-210 Mimic and Inhibitor Transfection

4.4. Ex Vivo miR-210 Mimic Transfection

4.5. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.6. Western Blotting

4.7. HΙF1α Expression Vector

4.8. Luciferase Assays

4.9. Immunofluorescence

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kawashima, N.; Okiji, T. Odontoblasts: Specialized hard-tissue-forming cells in the dentin-pulp complex. Congenit. Anom. 2016, 56, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jontell, M.; Okiji, T.; Dahlgren, U.; Bergenholtz, G. Immune Defense Mechanisms of the Dental Pulp. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 1998, 9, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, B.; Zheng, Y. The Roles and Molecular Mechanisms of HIF-1α in Pulpitis. J. Dent. Res. 2025, 104, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddlestone, J.; Bandarra, D.; Rocha, S. The role of hypoxia in inflammatory disease (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyeraas, K.J.; Berggreen, E. Interstitial Fluid Pressure in Normal and Inflamed Pulp. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 1999, 10, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lian, B.; Ma, L.; Zhao, J. Autophagy induced by hypoxia in pulpitis is mediated by HIF-1α/BNIP3. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2024, 159, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and Inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, K. Involvement of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in the Dysregulation of Oxygen Homeostasis in Sepsis. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2015, 15, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhausen, J.; Furuta, G.T.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Johnson, R.S.; Colgan, S.P.; Haase, V.H. Epithelial hypoxia-inducible factor-1 is protective in murine experimental colitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Mu, R.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Shao, W.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Su, Y.; et al. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α provoke toll-like receptor signalling-induced inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.T.; Colgan, S.P. Hypoxia and gastrointestinal disease. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 85, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, S.E.; O’Neill, L.A. HIF1α and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rius, J.; Guma, M.; Schachtrup, C.; Akassoglou, K.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S.; Haddad, G.G.; Karin, M. NF-κB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α. Nature 2008, 453, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, P.R.; Takahashi, Y.; Graham, L.W.; Simon, S.; Imazato, S.; Smith, A.J. Inflammation-regeneration interplay in the dentine-pulp complex. J. Dent. 2010, 38, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Zhang, W.; Ren, B.P.; Zeng, J.F.; Ling, J.Q. Expression of Toll Like Receptor 4 in Normal Human Odontoblasts and Dental Pulp Tissue. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutoh, N.; Tani-Ishii, N.; Tsukinoki, K.; Chieda, K.; Watanabe, K. Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 2 and 4 in Dental Pulp. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobert, O. Gene Regulation by Transcription Factors and MicroRNAs. Science 2008, 319, 1785–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.C. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mens, M.M.J.; Ghanbari, M. Cell Cycle Regulation of Stem Cells by MicroRNAs. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, D.; Zheng, L.; Huang, D.; Ye, L. Epigenetic regulation in dental pulp inflammation. Oral. Dis. 2017, 23, 22–28, Correction in Oral. Dis. 2017, 23, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Carrillo, J.L.; Vázquez-Alcaraz, S.J.; Vargas-Barbosa, J.M.; Ramos-Gracia, L.G.; Alvarez-Barreto, I.; Medina-Quiroz, A.; Díaz-Huerta, K.K. The Role of microRNAs in Pulp Inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, M.; Ghasemi, H.; Bazhan, D.; Mohammadi Bolbanabad, N.; Rahdan, F.; Arianfar, N.; Vahedi, F.; Khatami, S.H.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Aiiashi, S.; et al. MicroRNAs in disease States. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 569, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nara, K.; Kawashima, N.; Noda, S.; Fujii, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Tazawa, K.; Okiji, T. Anti-inflammatory roles of microRNA 21 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human dental pulp cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 21331–21341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kawashima, N.; Han, P.; Sunada-Nara, K.; Yu, Z.; Tazawa, K.; Fujii, M.; Kieu, T.Q.; Okiji, T. MicroRNA-27a-5p Downregulates Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Human Dental Pulp Cells via the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Sunada-Nara, K.; Kawashima, N.; Fujii, M.; Wang, S.; Kieu, T.Q.; Yu, Z.; Okiji, T. MicroRNA-146b-5p Suppresses Pro-Inflammatory Mediator Synthesis via Targeting TRAF6, IRAK1, and RELA in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Human Dental Pulp Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7433, Correction in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.Y.; Loscalzo, J. MicroRNA-210: A unique and pleiotropic hypoxamir. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagnini, G.; Greco, S.; Longo, M.; Maimone, B.; Voellenkle, C.; Fuschi, P.; Carrara, M.; Creo, P.; Maselli, D.; Tirone, M.; et al. Hypoxia-induced miR-210 modulates the inflammatory response and fibrosis upon acute ischemia. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 435, Correction in Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Das, S.; Kumar, A.; Abhishek, K.; Verma, S.; Mandal, A.; Singh, R.K.; Das, P. Leishmania donovani Activates Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α and miR-210 for Survival in Macrophages by Downregulation of NF-κB Mediated Pro-inflammatory Immune Response. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieran, N.W.; Suresh, R.; Dorion, M.F.; MacDonald, A.; Blain, M.; Wen, D.; Fuh, S.C.; Ryan, F.; Diaz, R.J.; Stratton, J.A.; et al. MicroRNA-210 regulates the metabolic and inflammatory status of primary human astrocytes. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Kawashima, N.; Tazawa, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Nara, K.; Noda, S.; Nagai, S.; Okiji, T. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α promotes interleukin 1β and tumour necrosis factor α expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human dental pulp cells. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyssonnaux, C.; Cejudo-Martin, P.; Doedens, A.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Johnson, R.S.; Nizet, V. Cutting Edge: Essential Role of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α in Development of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Sepsis. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 7516–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, S.R.; Print, C.; Farahi, N.; Peyssonnaux, C.; Johnson, R.S.; Cramer, T.; Sobolewski, A.; Condliffe, A.M.; Cowburn, A.S.; Johnson, N.; et al. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1α-dependent NF-κB activity. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chang, S.; Xu, R.; Chen, L.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Qian, J.; Zou, Y.; Ma, J. Hypoxia-challenged MSC-derived exosomes deliver miR-210 to attenuate post-infarction cardiac apoptosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, J.; Deng, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Feng, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-210 overexpression promotes psoriasis-like inflammation by inducing Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanovic, M.; Kracht, M.; Schmitz, M.L. The cytokine-induced conformational switch of nuclear factor κB p65 is mediated by p65 phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 2014, 457, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, F.; Smith, E.L.; Carmody, R.J. The Regulation of NF-κB Subunits by Phosphorylation. Cells 2016, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y.; Boyd, N.M.; Cringle, S.J.; Alder, V.A.; Yu, D.Y. Oxygen distribution and consumption in rat lower incisor pulp. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2002, 47, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Miyoshi, H.; Toriumi, W.; Sugita, T. Functional Interactions of Transforming Growth Factor β-activated Kinase 1 with IκB Kinases to Stimulate NF-κB Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 10641–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, H.; Campbell, D.G.; Burness, K.; Hastie, J.; Ronkina, N.; Shim, J.H.; Arthur, J.S.; Davis, R.J.; Gaestel, M.; Johnson, G.L.; et al. Roles for TAB1 in regulating the IL-1-dependent phosphorylation of the TAB3 regulatory subunit and activity of the TAK1 complex. Biochem. J. 2008, 409, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y.S.; Song, J.; Seki, E. TAK1 regulates hepatic cell survival and carcinogenesis. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Borodkin, V.S.; Albarbarawi, O.; Campbell, D.G.; Ibrahim, A.; van Aalten, D.M. O-GlcNAcylation of TAB1 modulates TAK1-mediated cytokine release. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cai, B.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, C.; Yi, F.; Liu, B.; Gao, C. TRIM26 positively regulates the inflammatory immune response through K11-linked ubiquitination of TAB1. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 3077–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; Bassi, R.; Gorog, D.A.; Saurin, A.T.; Jiang, J.; Heads, R.J.; Martin, J.L.; Davis, R.J.; Flavell, R.A.; Marber, M.S. Diverse Mechanisms of Myocardial p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation: Evidence for MKK-Independent Activation by a TAB1-Associated Mechanism Contributing to Injury During Myocardial Ischemia. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Bu, S.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Ju, C.; Huang, D.; Xu, W.; Tan, X.; Liang, M.; Deng, S.; et al. RNF207 exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy via post-translational modification of TAB1. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Bartz, S.; Mao, M.; Li, L.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. The Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2α N-Terminal and C-Terminal Transactivation Domains Cooperate to Promote Renal Tumorigenesis In Vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Accession No. | Size, Bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <human> | ||||

| ACTB | 5′-GTAGCACAGCTTCTCCTTAATGTCA-3′ | 5′-CTGACTGACTACCTCATGAAGATCC-3′ | NM_001101.3 | 102 |

| IL6 | 5′-TATACCTCAAACTCCAAAAGACCAG-3′ | 5′-ACAAGAGTAACATGTGTGAAAGCAG-3′ | NM_000600.4 | 157 |

| MCP1 | 5′-CACCTGCTGTTATAACTTCACCAAT-3′ | 5′-GTTGAAAGATGATAAGCCCACTCTA-3′ | NM_002982.4 | 130 |

| TNFα | 5′-CCTGGTATGAGCCCATCTATCTG-3′ | 5′-GCAATGATCCCAAAGTAGACCTG-3′ | NM_000594.3 | 130 |

| TAB1 | 5′-ATCCCTCAGTGCCAACTAAACC-3′ | 5′-GAAGATCCCAGTGCACAAGTCA-3′ | NM_153497.3 | 137 |

| <rat> | ||||

| Actb | 5′-GTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAACACAGT-3′ | 5′-GGAGCAATGATCTTGATCTTCATGG -3′ | NM_031144.3 | 127 |

| Il6 | 5′-TAAGGACCAAGACCATCCAACTCAT-3′ | 5′-AGTGAGGAATGTCCACAAACTGATA-3′ | NM_012589.2 | 125 |

| Mcp1 | 5′-CTAAGGACTTCAGCACCTTTGAATG-3′ | 5′-GTTCTCTGTCATACTGGTCACTTCT-3′ | NM_031530.1 | 120 |

| Tnfα | 5′-AAACGGAGCTAAACTACCAGCTATC-3′ | 5′-CCTGGTCACCAAATCAGCATTATTA-3′ | NM_012675.3 | 139 |

| Tab1 | 5′-TAGTGTCTGCTTCTGTTAGATCCTG-3′ | 5′-AATCAGCTTCCTCATCAGAGTGAAA-3′ | NM_001109976.2 | 134 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, X.; Kawashima, N.; Wang, S.; Han, P.; Fujii, M.; Sunada-Nara, K.; Yu, Z.; Okiji, T.; Yahata, Y. MicroRNA-210 Suppresses NF-κB Signaling in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Dental Pulp Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210837

Bai X, Kawashima N, Wang S, Han P, Fujii M, Sunada-Nara K, Yu Z, Okiji T, Yahata Y. MicroRNA-210 Suppresses NF-κB Signaling in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Dental Pulp Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210837

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Xiyuan, Nobuyuki Kawashima, Shihan Wang, Peifeng Han, Mayuko Fujii, Keisuke Sunada-Nara, Ziniu Yu, Takashi Okiji, and Yoshio Yahata. 2025. "MicroRNA-210 Suppresses NF-κB Signaling in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Dental Pulp Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210837

APA StyleBai, X., Kawashima, N., Wang, S., Han, P., Fujii, M., Sunada-Nara, K., Yu, Z., Okiji, T., & Yahata, Y. (2025). MicroRNA-210 Suppresses NF-κB Signaling in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Dental Pulp Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210837