2.1. Chemical Composition of Raw Materials and Bread

On a dry matter basis (

DM), wheat flour (WF) contained 0.73% ash, 2.96% dietary fiber, 12.64% protein, 1.78% fat, and 81.89% digestible carbohydrates. In comparison, lyophilized pomace derived from

Lonicera caerulea berries (LCP) exhibited higher contents of minerals, dietary fiber, and fat, while displaying lower levels of protein and digestible carbohydrates (

Table 1). Specifically, the mineral content in LCP was nearly fivefold higher than in WF, dietary fiber content was more than twelvefold higher, and fat content exceeded that of WF by more than twofold. Accordingly, the incorporation of increasing proportions of LCP into the bread formulation led to progressive rises in mineral, total dietary fiber, and fat contents, accompanied by reductions in protein and digestible carbohydrate levels. Notably, the enrichment in dietary fiber was substantial, as the fiber fraction in the fruit pomace is predominantly insoluble [

24]. Even the lowest inclusion level tested (1% LCP) resulted in a statistically significant increase in fiber content relative to the control bread.

Dietary fiber is well-established as a key contributor to health, associated with a lowered risk of prevalent chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colorectal cancer. These protective effects are largely attributable to the physicochemical characteristics of fiber, including its solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, which are crucial in digestive function and the regulation of blood glucose [

25,

26]. Soluble fibers can form viscous gels within the gastrointestinal tract, slowing gastric emptying and nutrient absorption, thereby enhancing postprandial glycemic control [

27]. Insoluble fibers facilitate intestinal transit and promote regular bowel function, while also supporting gut health by modulating the composition and activity of the microbiota. Furthermore, the microbial fermentation of fibers in the colon generates short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which exert systemic effects including the regulation of glucose metabolism, anti-inflammatory actions, and maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity [

28]. Collectively, these mechanisms underscore the multifaceted role of dietary fiber in glycemic management, gut health, and chronic disease prevention, highlighting its significance as a functional component of the diet [

25]. The dietary fiber content of fruit pomaces may vary considerably, ranging from approximately 35% to more than 80% on a DM basis [

29]. For instance, Sójka et al. [

30] demonstrated that chokeberry pomace comprises approximately 70% dietary fiber. Such variation can be attributed to multiple factors, including the type of fruit and the specific fruit components retained in the pomace, the cultivar and degree of ripeness, which influence the proportion of soluble and insoluble fiber. Additionally, the processing method—including juice extraction technique, use of enzymes, and intensity of pressing—determines the amount of residual pulp and skins in the pomace [

31]. Finally, post-processing treatments, such as drying method and parameters, can further impact both the total fiber content and the characteristics of its fractions [

32].

2.2. Flour Water Absorption and Dough Physical Properties

Farinographic assessment is widely employed to evaluate the baking performance of wheat flour. This method allows for the determination of flour water absorption, a parameter of considerable practical significance that directly affects dough and bread yield. Moreover, a farinograph records the physical properties of dough during mixing, including resistance to deformation and changes in consistency. Farinographic parameters often show significant correlations with bread quality [

33].

Partial replacement of WF with LCP had a significant impact on the water absorption of the blends and the rheological properties of the dough (

Table 2). Water absorption increased linearly with the level of LCP, ranging from 58.5% (C) to 60.6% (LCP6). Compared to the control, a statistically significant increase in water absorption was observed at 2% LCP and higher. The substitution of WF with LCP also resulted in prolonged dough development and stability times. These effects may be attributed to the higher fiber content of LCP compared to WF (

Table 1). Fiber-rich additives generally lead to increased flour water absorption and greater dough resistance to mixing, as indicated by the sum of dough development and stability times [

22,

34,

35]. However, this is not a universal rule. Recently, Cacak-Pietrzak et al. [

36] reported that partial replacement of refined wheat flour with ground cereal coffee reduced blend water absorption, had no effect on dough development time, but significantly prolonged dough stability. These discrepancies were most likely attributable to differences in the content and fractional composition of dietary fiber [

37]. Haskap berry pomace consists predominantly of water-insoluble fiber fractions, such as cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. In contrast, cereal coffee contains less dietary fiber than pomace, and it is mainly composed of water-soluble type II arabinogalactans and galactomannans [

38]. In the present study, substituting WF with LCP increased dough softening. At the highest level of LCP applied (6%), dough softening was more than twice that of the control. Increased dough softening indicates a weakening of gluten network strength and elasticity. As demonstrated by Nawrocka et al. [

35], competition for water between fiber and gluten during dough mixing leads to partial dehydration of the gluten network and structural changes, including the formation of gluten aggregates in β-sheet conformations stabilized by hydrogen bonds, which explains the observed modifications in dough rheological properties.

2.4. Crumb Texture

Texture constitutes a key parameter influencing consumer acceptance of bread. Bread texture is influenced by both the composition of raw materials and the applied technological process [

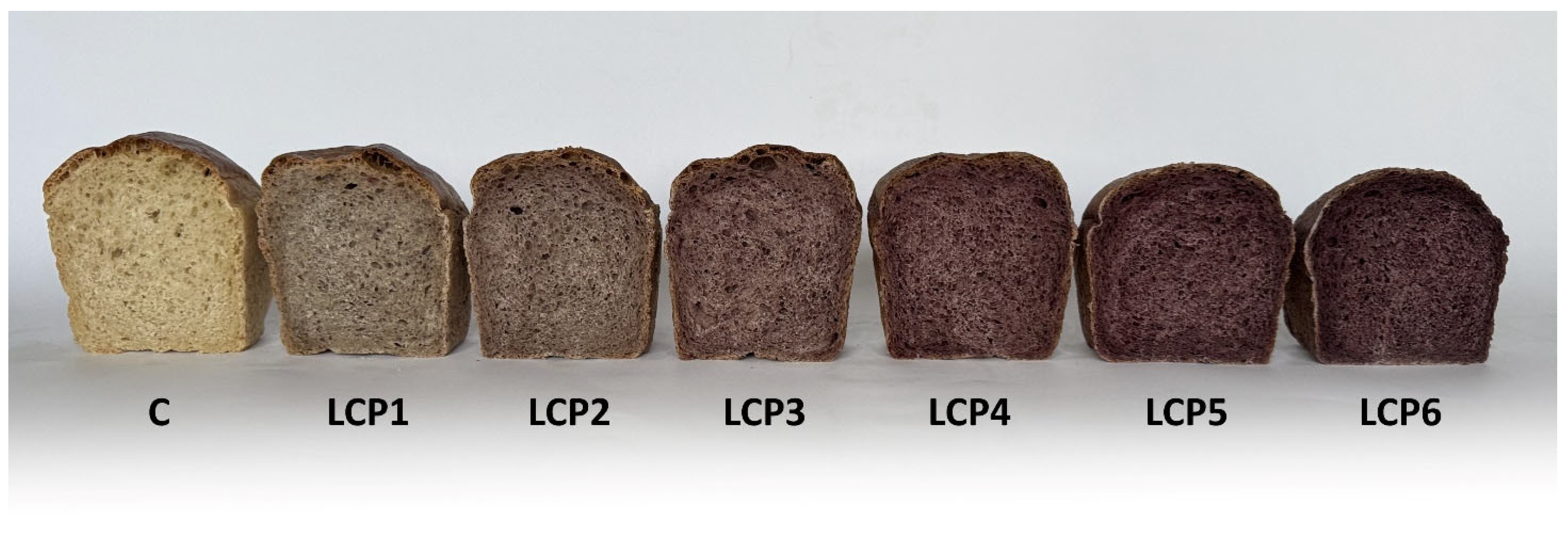

42]. The replacement of wheat flour with LCP at levels of 2% and above significantly increased the crumb hardness of fresh bread (measured three hours after baking) (

Table 4). Compared with the control sample, the crumb hardness of bread containing the highest tested level of LCP (6%) more than doubled (3.65 N vs. 8.77 N, respectively). This increase in crumb hardness can be attributed to the high dietary fiber content of LCP, which resulted in reduced loaf volume and a denser, more compact crumb structure. After 96 h of storage, staling led to a significant increase in crumb hardness across all bread samples, ranging from 7.56 N (C) to 18.95 N (LCP6).

In contrast, the substitution of wheat flour with LCP did not affect crumb elasticity, springiness, or cohesiveness. Elasticity and springiness of the crumb did not change significantly during storage, whereas the cohesiveness of all bread samples decreased by nearly half. Crumb chewiness increased linearly with the level of LCP incorporated into the bread formulation. After 96 h of storage, chewiness slightly increased, although the changes were not statistically significant.

Similar adverse effects of various plant-based additives on wheat bread texture were reported in our previous studies [

42,

43] and have likewise been documented by other researchers [

44,

45]. Bread crumb texture is primarily associated with the quantity and quality of gluten, which is responsible for gas retention during fermentation. Partial replacement of wheat flour with gluten-free raw materials reduces the gluten content, leading to decreased loaf volume and a denser, harder crumb [

44]. Likewise, incorporation of black chokeberry pomace at comparable levels led to a significant increase in crumb hardness and chewiness, which was evident even at a 2% addition [

22]. In contrast, in gluten-free bread, the incorporation of small amounts of berry pomace, such as raspberry or chokeberry, has relatively minor effects on crumb texture [

46]. This limited impact can be explained by the absence of gluten in the matrix. In wheat-based bread, gluten forms a viscoelastic protein network that interacts with fiber and water, contributing to crumb structure, elasticity, and firmness. Gluten-free breads rely mainly on starches and hydrocolloids to maintain structure, so small amounts of berry pomace do not significantly alter the matrix. Furthermore, the distribution and water-binding properties of fiber in gluten-free dough differ from those in wheat dough, further reducing the effect of pomace on texture.

2.5. Bread Microstructure Results

The microstructure of bread consists of pores formed during gas release in the dough fermentation process and the retention of gas throughout fermentation and baking [

47]. High-quality bread should be porous, with small and uniform pores, as such a microstructure is preferred by consumers [

48].

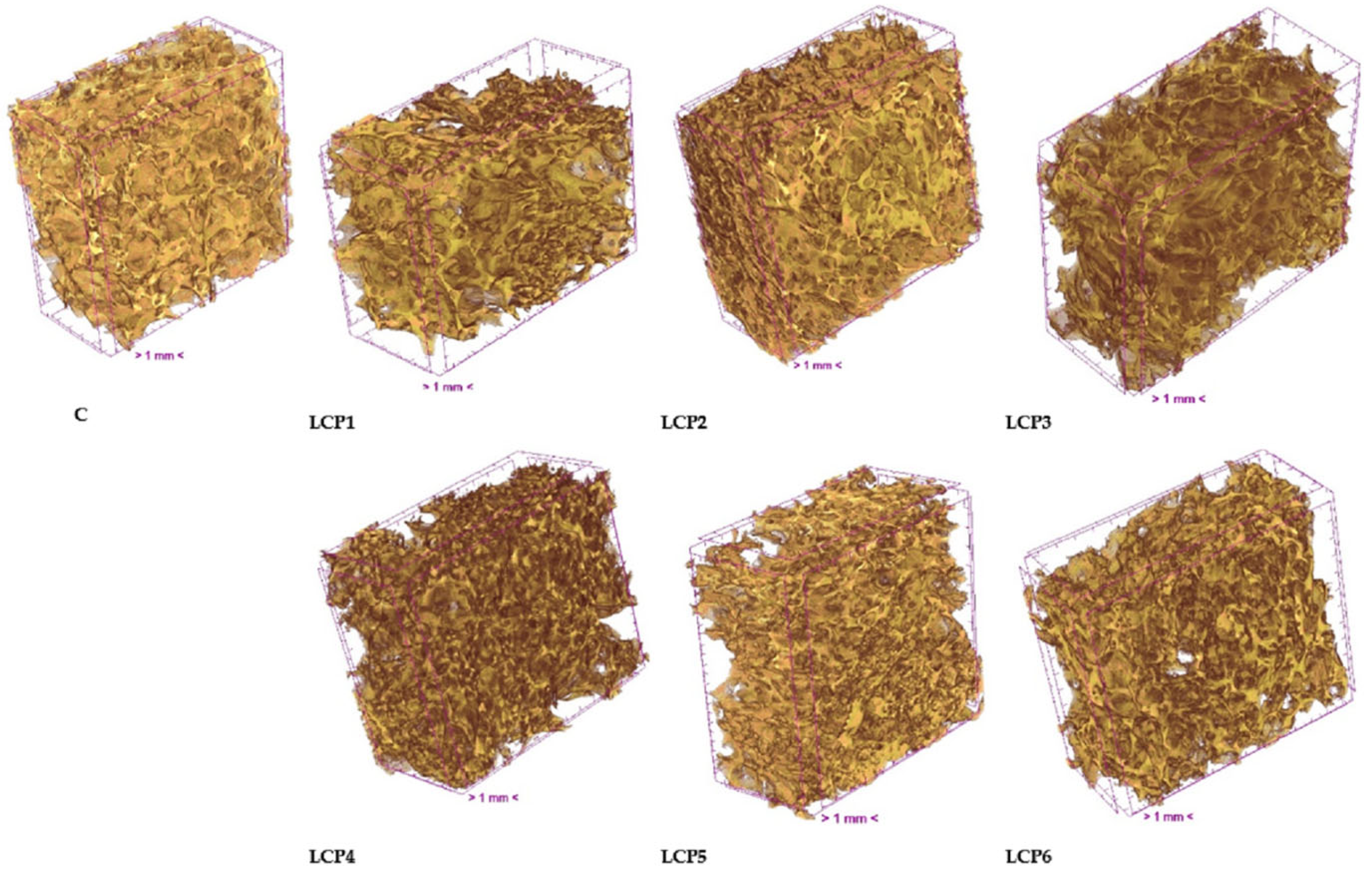

Figure 1 presents the 3D microstructure of bread measured using X-ray microtomography. All bread types exhibited a porous microstructure. The highest total porosity (76.78%) was observed in bread without the addition of freeze-dried haskap berry pomace (

Table 5). The addition of pomace to bread increased the percent object volume while simultaneously reducing total porosity. Although both percent object volume and total porosity in bread with added freeze-dried haskap pomace changed by more than 10 percentage points compared to the control bread, these differences were not statistically significant. This lack of significance is likely due to the high standard deviation observed for measurements of bread with pomace, indicating a more heterogeneous microstructure compared to the control.

Closed porosity was low and was statistically higher (1.89%) only in bread with 2% pomace addition, compared to 0.93% in the control bread (

Table 5). Open porosity is defined as the difference between total porosity and closed porosity. The microstructure of all bread samples was characterized by open porosity.

The primary parameter characterizing the average complexity of the structure is the object surface/volume ratio (OSVR) [

49]. Statistically significant differences in OSVR were observed among the breads (

Table 5). A significantly higher OSVR (15.60%) was recorded for bread with 2% pomace addition compared to the control. Higher levels of pomace addition had no statistically significant effect on OSVR. The degree of anisotropy (DA) is a measure of 3D structural symmetry, which in this study refers to pore arrangement. A value of 0 indicates complete isotropy, whereas a value of 1 indicates complete anisotropy [

50]. The addition of pomace had no significant effect on structure thickness or DA. DA values significantly above 1 indicate an anisotropic microstructure in all bread types analyzed.

The control bread exhibited the most uniform pore size distribution, containing 80% fine pores smaller than 0.5 mm

2, 17% pores between 0.5 and 1 mm

2, and only 3% pores between 1 and 1.5 mm

2. The pore surface area distribution changed significantly with the addition of LCP. In breads containing 1%, 2%, and 3% LCP, the proportion of fine pores decreased to 23%, 34%, and 52%, respectively, while the proportion of pores larger than 0.5 mm

2 increased to 60%, 40%, and 25%. The number of large pores exceeding 1 mm

2 rose sharply. The addition of 4%, 5%, or 6% LCP also reduced the proportion of fine pores compared to the control bread. Breads with 4%, 5%, and 6% LCP exhibited a more uniform pore size distribution than those with 1%, 2%, or 3% LCP, containing very few pores larger than 1 mm

2, at 1%, 6%, and 1%, respectively (

Figure S1).

2.8. Identification and Quantification of Phenolics

Table 8 presents the concentrations of phenolic acids identified in the raw materials and enriched bread samples. In LCP, neochlorogenic acid and chlorogenic acid predominated. Chlorogenic acid and its isomer, neochlorogenic acid, are among the most important naturally occurring phenolic acids found in fruits, vegetables, and coffee. Both compounds exhibit strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making them significant dietary constituents with potential health benefits [

54]. Chlorogenic acid has been extensively studied for its effects on glucose and lipid metabolism [

55], whereas neochlorogenic acid, although less widespread, demonstrates comparable biological activity, differing mainly in terms of bioavailability and chemical stability [

56]. Their occurrence in plant-derived products contributes to the functional properties of foods and may support the prevention of lifestyle-related diseases [

57]. Other authors observed that chokeberry and apple pomace are also significant sources of this compound [

58,

59]. In addition to chlorogenic and neochlorogenic acids, LCP was also found to contain cryptochlorogenic acid and protocatechuic acid. Trace amounts of

p-coumaric acid, salicylic acid, and syringic acid were also detected. In wheat flour, among the listed compounds, chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, and protocatechuic acid were identified, with chlorogenic acid being dominant; however, its concentration was approximately 200-fold lower than in LCP.

The enrichment of bread with LCP resulted in increased concentrations of chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, and

p-coumaric acid. The concentration of syringic acid also increased, but only at the 1% and 2% substitution levels of wheat flour with pomace. At higher substitution levels, the control bread contained more syringic acid than the enriched samples. This phenomenon may be attributed to the binding of syringic acid to dietary fiber and proteins, which reduces the detectable amount of this compound in the final product. Moreover, both wheat flour and LCP contained only trace amounts of

p-coumaric acid; nevertheless, in the enriched bread, this compound was detected, and its concentration was directly proportional to the proportion of LCP in the bread formulation. This can primarily be explained by the impact of the baking process and the food matrix. During thermal processing, certain phenolic compounds present in LCP become more bioaccessible, as they are released from complexes with dietary fiber and proteins, thereby increasing their detectable concentration in the final product [

60]. In other words, although the raw materials initially contained only trace amounts of

p-coumaric acid, its concentration in bread likely increased due to enhanced extraction and release during baking.

p-Coumaric acid is a natural hydroxycinnamic acid found in many plants, including cereal grains, fruits, and vegetables. It exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and may contribute to cellular protection against oxidative stress, as well as modulate the activity of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism [

61].

When analyzing the flavonoid aglycones identified in raw materials and enriched bread, it was observed that LCP were particularly rich in quercetin, containing more than two thousand times the amount present in wheat flour (

Table 9). Other authors have also observed that black chokeberry pomace constitutes a valuable source of quercetin [

58]. Moreover, the pomace contained substantial amounts of catechin and quercetin (23,750 ng/g dry mass (DM) and 19,187.5 ng/g DM, respectively), whereas wheat flour contained only trace levels. Quercetin is a naturally occurring flavonoid found in fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain products. Among flavonols, quercetin shows the greatest bioaccessibility in both fruits and pomace, with black chokeberry pomace demonstrating that it undergoes little degradation during digestion [

58]. It exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, supports cardiovascular health as well as glucose and lipid metabolism, and may also modulate immune responses [

62]. Catechin likewise displays potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, with potential cardioprotective effects [

63]. The incorporation of LCP into bread led to increased levels of quercetin, catechin, and lutein. Interestingly, certain compounds, such as taxifolin, eriodictyol, and isorhamnetin, were not detectable in the pomace itself but appeared in bread at higher LCP supplementation levels (2–4%). This phenomenon is most likely attributable to the baking process, which facilitates the release of these compounds from complexes with dietary fiber and proteins [

64].

When analyzing the flavonoid glycosides identified in raw materials and enriched bread, it was found that LCP were particularly rich in rutin and isoquercetin, whereas wheat flour contained only minor amounts of rutin—more than 400-fold lower than the concentration observed in LCP. High contents of these compounds have also been reported in pear pomace [

65]. Rutin, also referred to as vitamin P or rutoside, has been investigated for a wide range of pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, vasoprotective, cardioprotective, antithrombotic, and neuroprotective effects, making it a compound of considerable interest in both nutritional and therapeutic contexts [

66,

67]. Recent studies further indicate that isoquercetin exerts beneficial effects against neurodegenerative disorders [

68] as well as cancer-related diseases [

69].

In addition, the following flavonoid glycosides were identified in the pomace: isoquercetin, luteolin-7-glucoside, narcissoside, kaempferol-3-rutinoside, naringenin-7-O-glucoside, and narirutin. None of these compounds were detected in wheat flour. Substitution of wheat flour with as little as 1% LCP resulted in the appearance of rutin, narcissoside, kaempferol-3-rutinoside, and luteolin-7-glucoside in bread, with their concentrations increasing proportionally with the level of LCP supplementation. At 2% LCP substitution, all of the aforementioned flavonoid glycosides were detected, except for narirutin, which was only observed at 4% substitution. As in the pomace, rutin and isoquercetin were the most abundant compounds in the enriched bread.

A substantial body of scientific research underscores the health-promoting properties of phenolic compounds and dietary fiber. These bioactive constituents frequently co-occur in plant-derived foods, especially in pomace, thereby providing opportunities for interactions [

70]. Such interactions may involve both reversible noncovalent bonds and predominantly irreversible covalent linkages, forming the basis of the so-called carrier effect of dietary fiber in the gastrointestinal tract. Through this mechanism, fiber can modulate the release, stability, and overall bioavailability of phenolics, thereby playing a key role in their physiological and health-promoting effects [

71].

In the case of bread fortified with LCP, these fiber–phenolic interactions are particularly significant. LCP is a rich source of both dietary fiber and a wide spectrum of polyphenolic compounds. Within the bread matrix, phenolics can associate with both soluble and insoluble fiber fractions via hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and covalent ester linkages. These associations can markedly influence the release and bioaccessibility of phenolics during digestion [

72].

While the binding of haskap phenolics to fiber may reduce their immediate release in the upper gastrointestinal tract, potentially lowering apparent bioavailability and underestimating antioxidant activity if only small-intestinal absorption is considered, these interactions may also be advantageous. Fiber-bound phenolics are more likely to reach the colon intact, where microbial fermentation can cleave the complexes, liberating phenolics and producing smaller metabolites, such as phenolic acids, which exert both local and systemic effects [

73].

The functional outcome largely depends on the physicochemical characteristics of the bread matrix. Soluble fibers in the pomace can form viscous gels that entrap different phenolics, whereas insoluble fibers (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) may act as carriers, physically embedding polyphenols [

74]. Moreover, the molecular size and polarity of anthocyanins and phenolic acids influence whether they remain tightly bound to fiber or are gradually released during digestion [

75,

76].

Furthermore, incorporating LCP into bread formulations may influence the release and bioavailability of bioactive compounds, including polyphenols and dietary fiber, through both compositional and structural modifications of the bread matrix. Thermal processing during baking can facilitate the partial release of phenolic compounds bound to plant cell walls, potentially enhancing their bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity [

64]. At the same time, high temperatures may cause the degradation of thermolabile compounds, thereby reducing the nutritional potential of certain bioactives [

77]. Future research should use in vitro digestion and colonic fermentation models to assess how interactions between LCP and dietary fiber influence the stability, release, and biotransformation of phenolics in enriched bread, as high fiber and polyphenol content—such as in Haskap pomace—may slow starch digestion and affect bioavailability depending on thermal, matrix, and storage conditions, highlighting the need to evaluate both bioaccessibility and bioavailability in fortified baked goods.