A Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Dynamic Discriminatory Pricing Model for Hotel Rooms with Fairness Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose a dynamic discriminatory pricing framework for hotel rooms with fairness constraints. By adjusting the group and temporal fairness parameters, this framework can be transformed into four distinct pricing models: fixed pricing, dynamic pricing, discriminatory pricing, and dynamic discriminatory pricing. This framework extends the theoretical foundations of hotel room pricing optimization. It can effectively address the limitation of traditional models that only solve pricing problems in a single scenario, significantly enhancing the model’s generality.

- (2)

- We revise the representation of the fairness gap in the fairness constraints, shifting from the price range of the optimal pricing strategy to customers’ acceptable real fairness perception. This revision is more aligned with the characteristics of the customer groups of a specific hotel. Compared with the methods [9,10] that determine the fairness gap based on the optimal solution of unconstrained models, the fairness gap derived from this method exhibits better determinacy and applicability. Hence, the model-derived solutions for pricing strategies can be more effective in practice.

- (3)

- To solve the dynamic discriminatory pricing model with fairness constraints, we propose a two-stage deep reinforcement learning algorithm. This algorithm can generate optimal pricing strategies that satisfy fairness constraints based on the dynamic changes in the market environment, and it is more applicable and faster-running than traditional nonlinear programming algorithms. This algorithm provides a new solution method for intelligent pricing problems with temporal constraints, expanding the application scope of deep reinforcement learning algorithms in the pricing field.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hotel Room Pricing Strategy

2.2. Pricing Models for Hotel Rooms

2.3. Pricing Fairness

3. Hotel Room Pricing Model

3.1. Model Assumptions

- (1)

- All rooms in the hotel are homogeneous, that is, we only consider a single room type.

- (2)

- Customers can be segmented into distinct groups, where individuals within the same group are assumed to be homogeneous. This homogeneity means that all members of a group share similar preferences for hotel room prices and demonstrate consistent levels of concern about price fairness.

- (3)

- For customers staying consecutively, room prices remain consistent with the initial booking price throughout their entire stay and will not fluctuate.

- (4)

- In the initial state of our simulation, all the hotel rooms are unoccupied.

3.2. Notations and Variable Definitions

3.3. Optimization Model

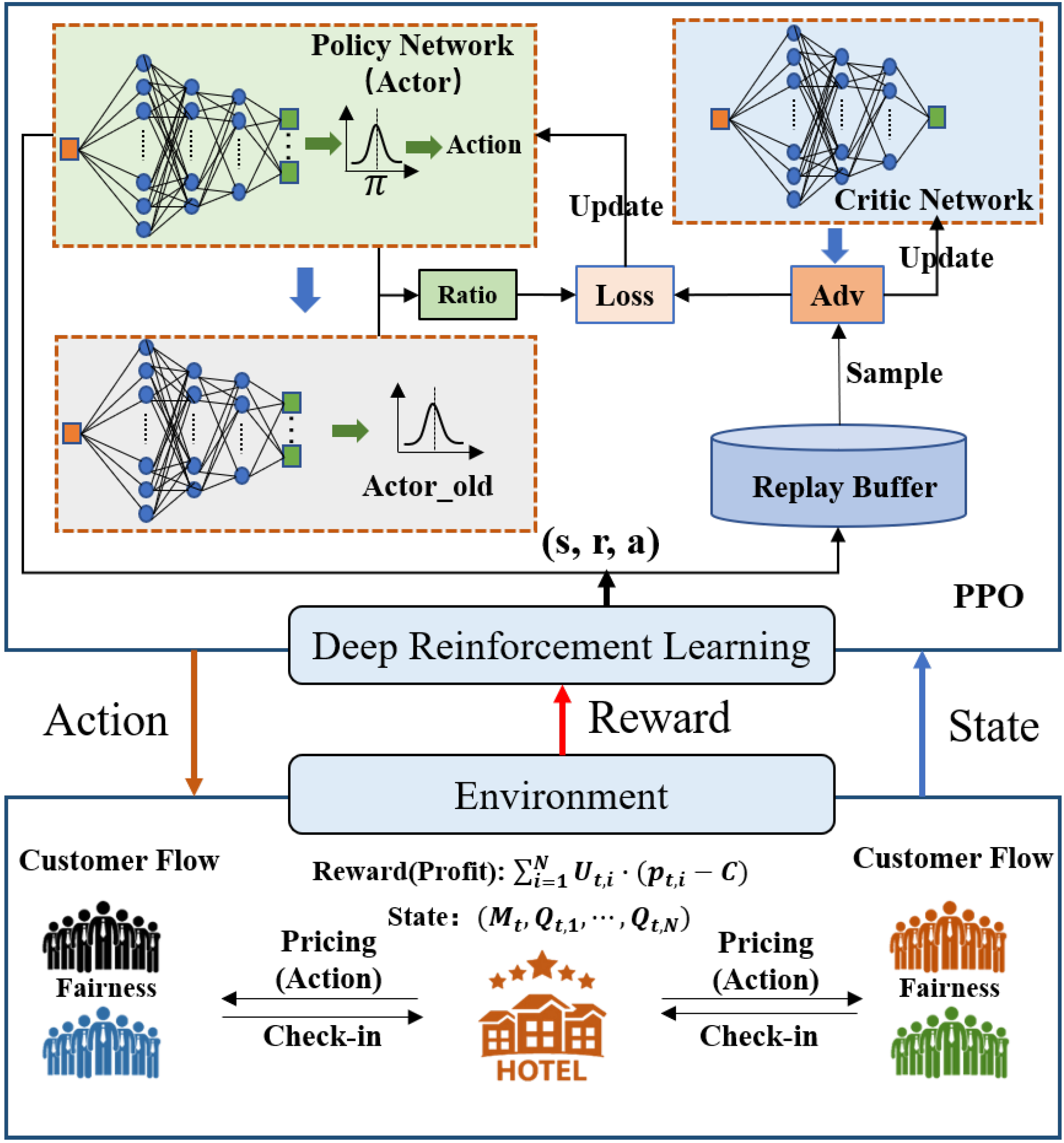

4. Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm

4.1. The MDP Model for Hotel Room Pricing

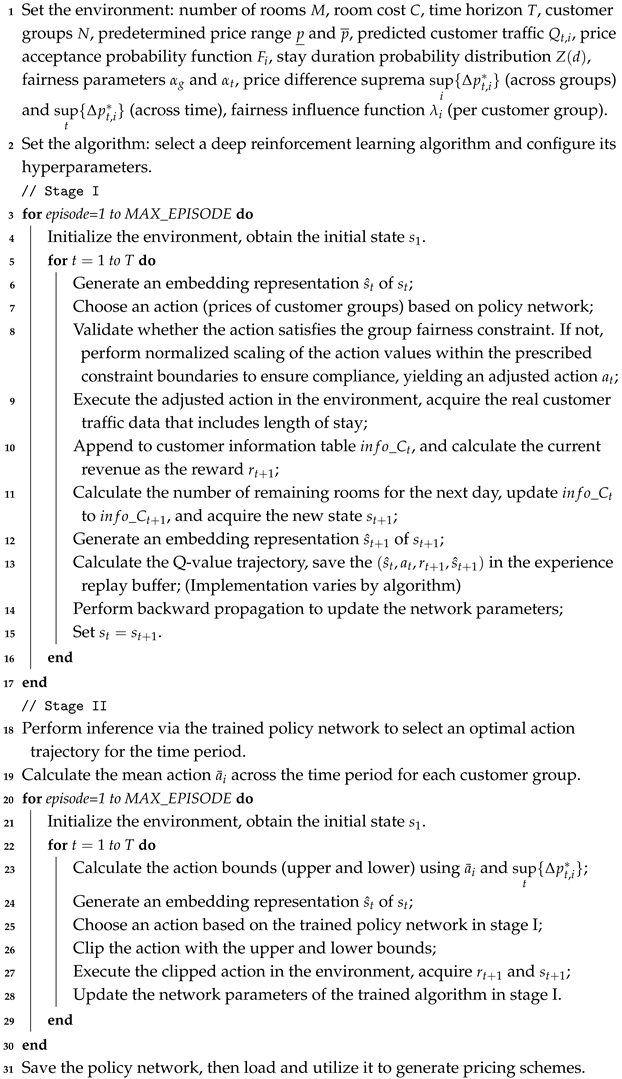

4.2. Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Two-stage deep reinforcement learning algorithm |

|

5. Case Study

5.1. Target Hotel and Model Parameters

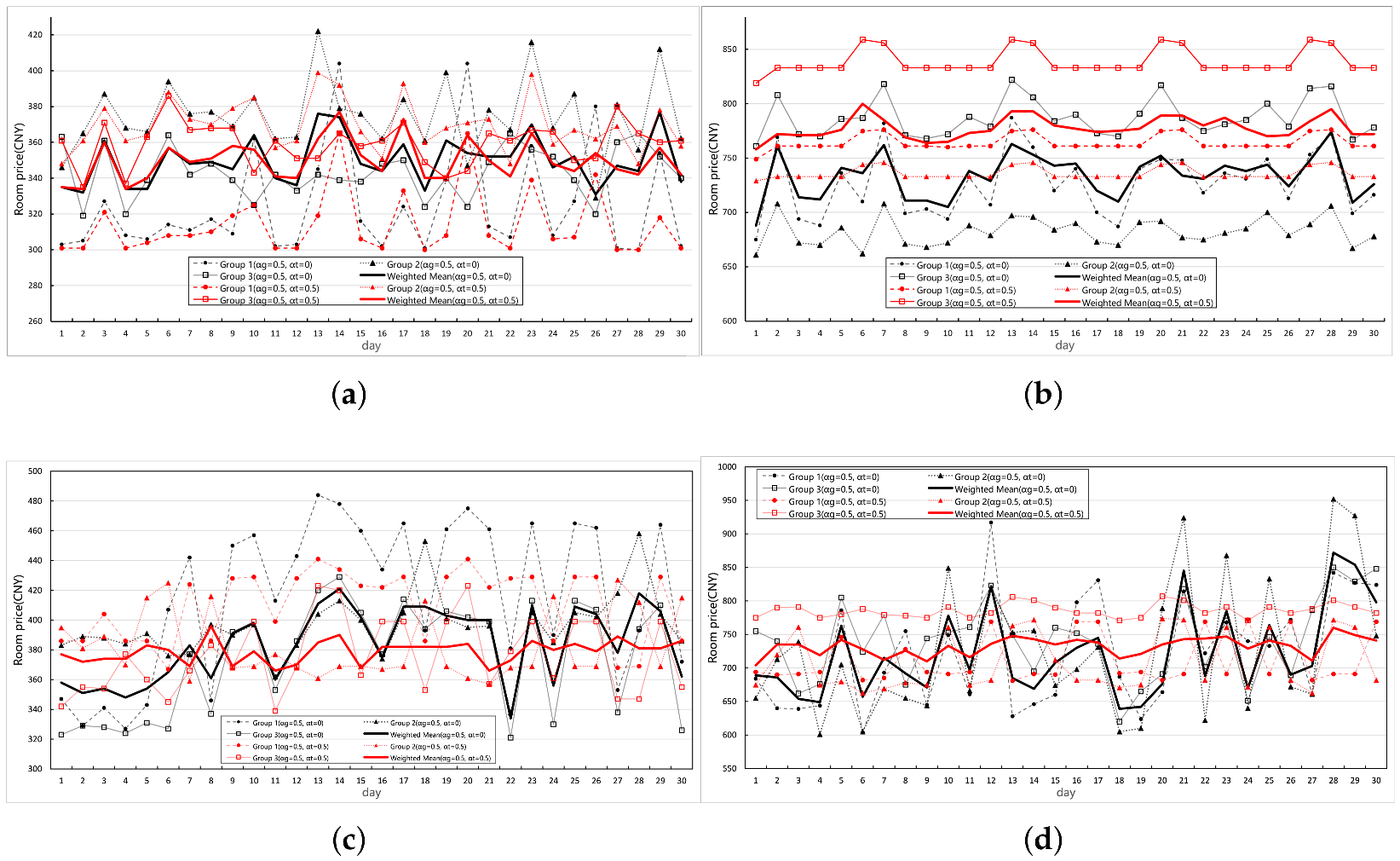

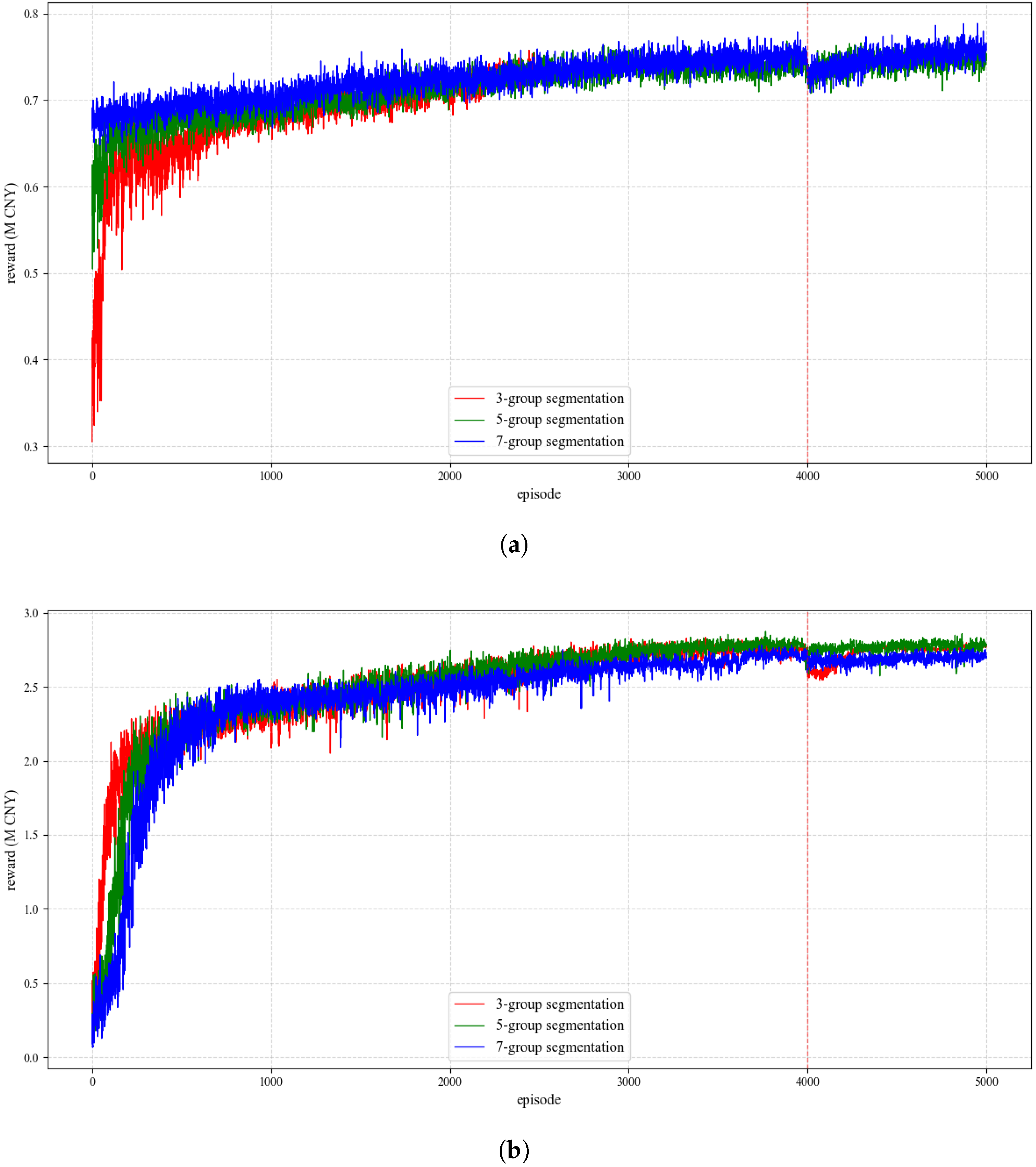

5.2. Results Analysis

5.3. Algorithm Comparison

5.4. Supplementary Experiments

5.5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Den, B.; Arnoud, V. Dynamic pricing and learning: Historical origins, current research, and new directions. Surv. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2015, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L.; Viglia, G.; Nieto-Garcia, M. Strategic consumer behavior in online hotel booking. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Pang, T.T.; Kuslina, B.H. The effect of price discrimination on fairness perception and online hotel reservation intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1320–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, E. Big data and personalized pricing. Bus. Ethics Q. 2020, 30, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Pawłowska-Nowak, M. Dynamic pricing method in the E-commerce industry using machine learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y. The impact of algorithmic price discrimination on consumers’ perceived betrayal. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 825420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A.; Saleh, M.; Rasmy, M.H.; ElShishiny, H. Dynamic room pricing model for hotel revenue management systems. Egypt. Inform. J. 2011, 12, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadly, M.; Ridwan, A.Y.; Akbar, M.D. Hotel room price determination based on dynamic pricing model using nonlinear programming method to maximize revenue. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Information Technology and Innovation (ICAITI), Bali, Indonesia, 21–22 September 2019; pp. 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.C.; Elmachtoub, A.N.; Lei, X. Price discrimination with fairness constraints. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 8536–8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.C.; Miao, S.; Wang, Y. Dynamic pricing with fairness constraints. Oper. Res. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Del Chiappa, G.; Andy, H. The research-practice gap in hotel revenue management: Insights from Italy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, R.; Duque, J.; Rubio, A.; Arevalo, J. Reinforcement learning for fair dynamic pricing. In Proceedings of the the 2018 Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys), London, UK, 6–7 September 2018; Volume 868, pp. 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhead, R.; Gosavi, A. A bounded actor-critic reinforcement learning algorithm applied to airline revenue management. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 82, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondoux, N.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Fiig, T.; Acuna-Agost, R. Reinforcement learning applied to airline revenue management. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2020, 19, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Huang, M.; Gao, Z.; Wang, X. Distributed dynamic pricing of multiple perishable products using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dreessen, L.; Schlosser, R. Reinforcement learning versus data-driven dynamic programming: A comparison for finite horizon dynamic pricing markets. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncay, G.; Kaya, K.; Yilmaz, Y.; Yaslan, Y.; Ögüdücü, S. A reinforcement learning based dynamic room pricing model for hotel industry. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2024, 62, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, M.; Piga, C.; Pozzi, A. From uniform to bespoke prices: Hotel pricing during EURO 2016. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2023, 21, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Takahashi, A.; Koide, N.; Ichifuji, Y. Application of online booking data to hotel revenue management. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Silva, L.; Marques, J. Data Science in supporting hotel management: Application of predictive models to booking.com guest evaluations. In Proceedings of the Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems, ICOTTS 2023, Bacalar, Mexico, 2–4 November 2023; Volume 384, pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Qian, J.; Chen, J.; Chen-hung, W. Customized regression model for airbnb dynamic pricing. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference of Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A.; Jacob, M. Dynamic pricing for online hotel demand: The case of resort hotels in Majorca. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, P.B.; Monson, C.K.; Seppi, K.D.; Warnick, S.C. Particle swarm optimization in dynamic pricing. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–21 July 2006; pp. 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xia, Y. A nonatomic-game approach to dynamic pricing under competition. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2013, 22, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, A.E.M.; Saleh, M.; Atiya, A.F.; Aziz, H.A. Dynamic pricing for hotel revenue management using price multipliers. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2013, 12, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Xiao, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wu, M.; Ni, S. Modeling price elasticity for occupancy prediction in hotel dynamic pricing. In Proceedings of the CIKM’22: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Managemen, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 4742–4746. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zheng, W. Hotel demand forecasting: A comprehensive literature review. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Niu, B. Leveraging online reviews for hotel demand forecasting: A deep learning approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, C.; Zheng, W. Daily hotel demand forecasting with spatiotemporal features. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 35, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, M.; Zhao, E.; Sun, S.; Wang, S. Can multi-source heterogeneous data improve the forecasting performance of tourist arrivals amid COVID-19? Mixed-data sampling approach. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.; Hong, S.H.; Zhang, X. A dynamic pricing demand response algorithm for smart grid: Reinforcement learning approach. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrahi, F.; Eisend, M.; Dost, F. A meta-analysis of price change fairness perceptions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Jain, S. Behavior-based pricing: An analysis of the impact of peer-induced fairness. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2705–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallus, N.; Zhou, A. Fairness, welfare, and equity in personalized pricing. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event, 3–10 March 2021; pp. 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kamble, V. Individual fairness in hindsight. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–35. Available online: http://jmlr.org/papers/v22/19-658.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing function approximation error in Actor-Critic methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Volume 80, pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Modeling and forecasting hotel room demand based on advance booking information. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajpai, G.N. Managing overbooking in hotels: A probabilistic model using Poisson distribution. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2018, 4, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wu, D.; Xu, H. Signaling or not? The pricing strategy under fairness concerns and cost information asymmetry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 321, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazgal, A.; Soberman, D. Behavior-based discrimination: Is it a winning play, and if so, when? Mark. Sci. 2008, 27, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Sudhir, K. A customer management dilemma: When is it profitable to reward one’s own customers? Mark. Sci. 2010, 29, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrate, G.; Fraquelli, G.; Viglia, G. Dynamic pricing strategies: Evidence from European hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Season | Weekend | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off-season | Weekdays | 1 | Poisson(27) | ||

| 2 | Poisson(39) | ||||

| 3 | Poisson(25) | ||||

| Weekends | 1 | Poisson(32) | |||

| 2 | Poisson(46) | ||||

| 3 | Poisson(24) | ||||

| Peak-season | Weekdays | 1 | Poisson(73) | ||

| 2 | Poisson(52) | ||||

| 3 | Poisson(37) | ||||

| Weekends | 1 | Poisson(90) | |||

| 2 | Poisson(64) | ||||

| 3 | Poisson(42) |

| Off-Season | Peak-Season | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRR | Profit | DGA | ROP | MRR | Profit | DGA | ROP | ||

| 0.5 | 0.3 | 348 | 0.734 | 74 | 86.5% | 779 | 2.782 | 83 | 100% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 350 | 0.752 | 74 | 88.6% | 778 | 2.785 | 85 | 100% |

| 0.5 | 0.7 | 350 | 0.770 | 76 | 90.9% | 779 | 2.798 | 84 | 100% |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 361 | 0.748 | 71 | 83.1% | 773 | 2.769 | 84 | 100% |

| 0.7 | 0.5 | 350 | 0.771 | 76 | 91.4% | 781 | 2.803 | 84 | 100% |

| DDP-N | 371 | 0.835 | 75 | 89.3% | 822 | 2.913 | 82 | 100% | |

| DP-N | 372 | 0.783 | 69 | 83.1% | 783 | 2.802 | 83 | 100% | |

| Hyperparameters | PPO | DDPG | TD3 | AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actor learning rate | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | / | 0.0001 |

| Critic learning rate | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | / | 0.0002 |

| Soft update coefficient | / | 0.01 | 0.01 | / |

| Q-network learning rate | / | / | 0.0003 | / |

| Policy network learning rate | / | / | 0.0003 | / |

| Reward discount rate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Training episodes | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Days per episode | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Algorithms | Profit (M) | Training (Running) Time | Episodes (Iterations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPO (Off-season, DDP-C) | 0.752 | 25 m | 2500 |

| PPO (Peak-season, DDP-C) | 2.785 | 50 m | 5000 |

| PPO (Off-season, DDP-N) | 0.835 | 20 m | 2000 |

| PPO (Peak-season, DDP-N) | 2.913 | 40 m | 4000 |

| PSO (Off-season, DDP-C) | 0.789 | 35 m | 5000 |

| PSO (Peak-season, DDP-C) | 2.822 | 35 m | 5000 |

| PSO (Off-season, DDP-N) | 0.638 | >1 h | 10,000 |

| PSO (Peak-season, DDP-N) | 2.398 | >1 h | 10,000 |

| Historical Data (Off-season) | 0.703 | / | / |

| Historical Data (Peak-season) | 2.658 | / | / |

| Hotel | Algorithms | Off-Season Profit (M) | Peak-Season Profit (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel BH | PPO (DDP-C) | 0.631 | 1.418 |

| PPO (DDP-N) | 0.741 | 1.624 | |

| PSO (DDP-C) | 0.661 | 1.486 | |

| PSO (DDP-N) | 0.680 | 1.555 | |

| Historical Data | 0.630 | 1.400 | |

| Hotel HJ | PPO (DDP-C) | 1.819 | 3.125 |

| PPO (DDP-N) | 1.954 | 3.514 | |

| PSO (DDP-C) | 1.824 | 3.250 | |

| PSO (DDP-N) | 1.771 | 3.377 | |

| Historical Data | 1.670 | 2.970 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Jian, L.; Liu, W.; Lv, W. A Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Dynamic Discriminatory Pricing Model for Hotel Rooms with Fairness Constraints. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040337

Wang X, Xie Y, Jian L, Liu W, Lv W. A Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Dynamic Discriminatory Pricing Model for Hotel Rooms with Fairness Constraints. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040337

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinmin, Yuwei Xie, Ling Jian, Wei Liu, and Wenting Lv. 2025. "A Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Dynamic Discriminatory Pricing Model for Hotel Rooms with Fairness Constraints" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040337

APA StyleWang, X., Xie, Y., Jian, L., Liu, W., & Lv, W. (2025). A Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Dynamic Discriminatory Pricing Model for Hotel Rooms with Fairness Constraints. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040337