What Does Bullet Screen Bring to Video Platform? A Theoretical Analysis Comparing Different Bullet Screen Modes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How the video platform should formulate its bullet screen and advertising strategies under the bilateral market structure? In particular, how should the platform make decisions when consumers have different preferences for bullet screens?

- How do platform strategies change under different bullet screen models?

- How should the video platform choose the right bullet screen features?

2. Literature Review

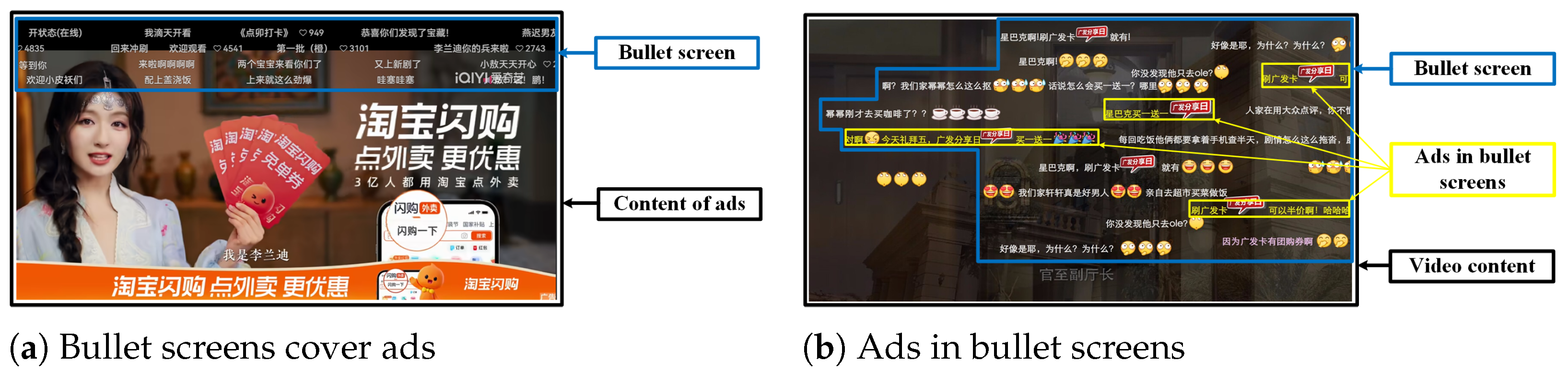

2.1. Bullet Screens in Video Platforms

2.2. Pricing Strategies for Video Platforms

2.3. Two-Sided Market Theory

2.4. Comparison and Contribution

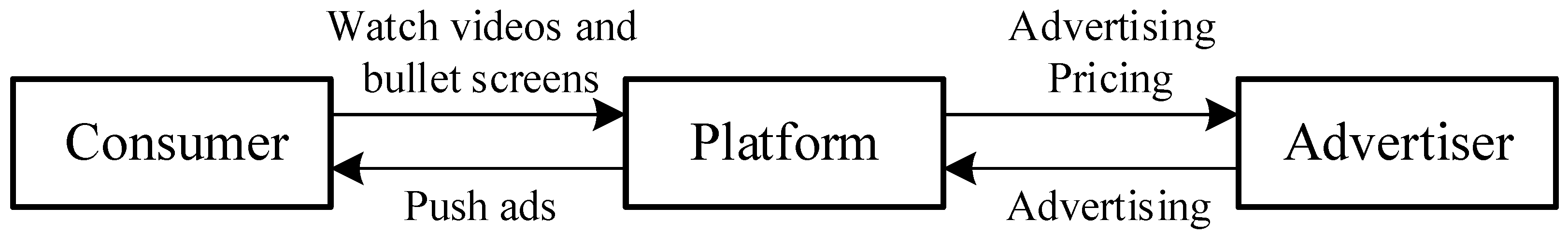

3. Model Description and Solution

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Model and Analysis

3.2.1. Base Model

- (a)

- The platform’s bullet screen quality and ad pricing will both rise.

- (b)

- When , the platform’s consumer size will increase. Conversely, when , the consumer size decreases.

- (c)

- When , the advertiser size and profit level of the platform will increase. Conversely, when , advertiser size and profit level decrease.

3.2.2. Platform Allows Bullet Screens to Cover Ads

3.2.3. Platforms Allow Ads in Bullet Screens

- (a)

- Both the platform’s bullet screen quality and ad pricing will increase.

- (b)

- When , the platform’s consumer size increases. Conversely, when , the consumer size decreases.

- (c)

- When , the platform’s advertiser size and profit level will increase. Conversely, when , advertiser size and profit level will decrease.

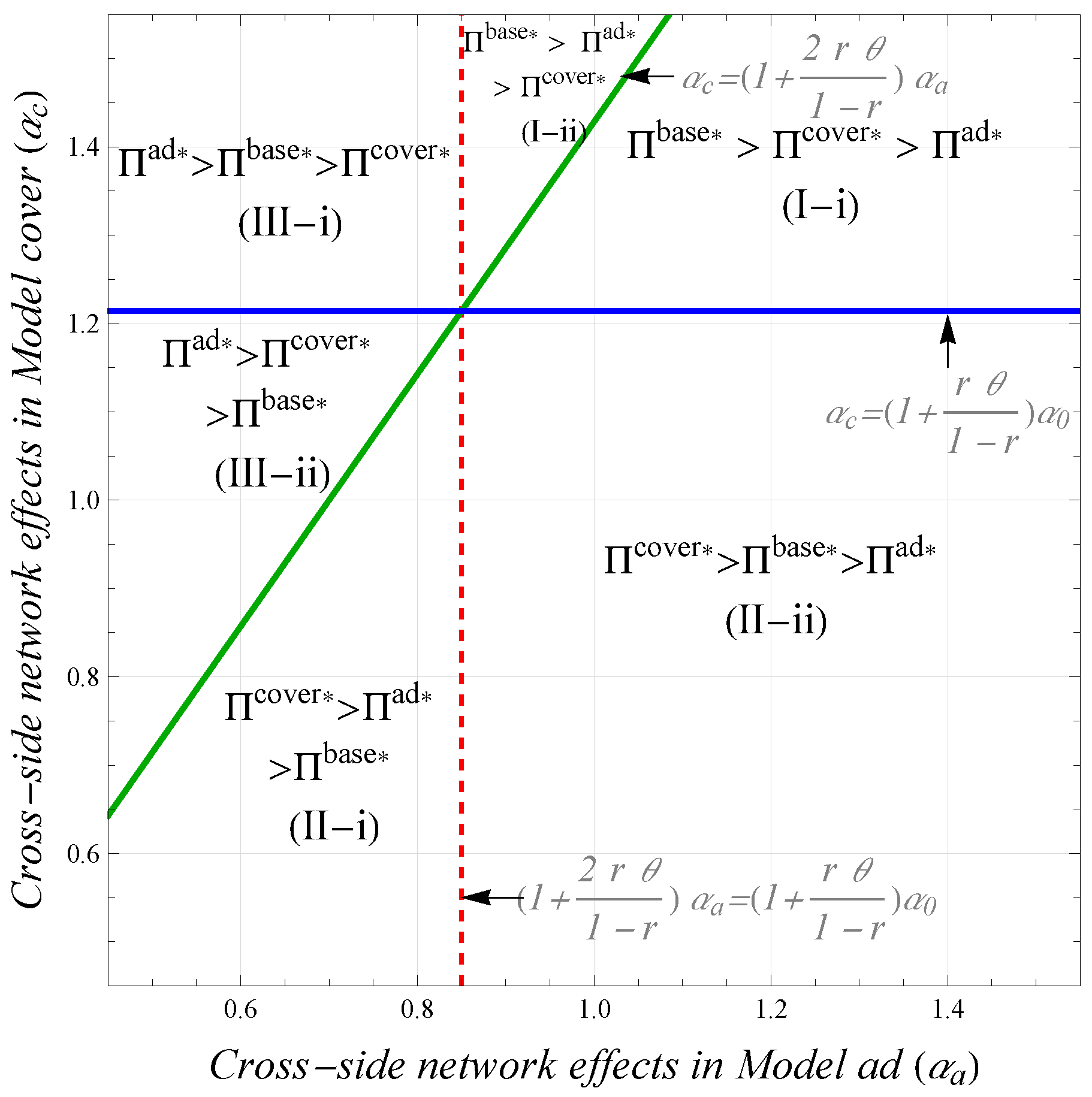

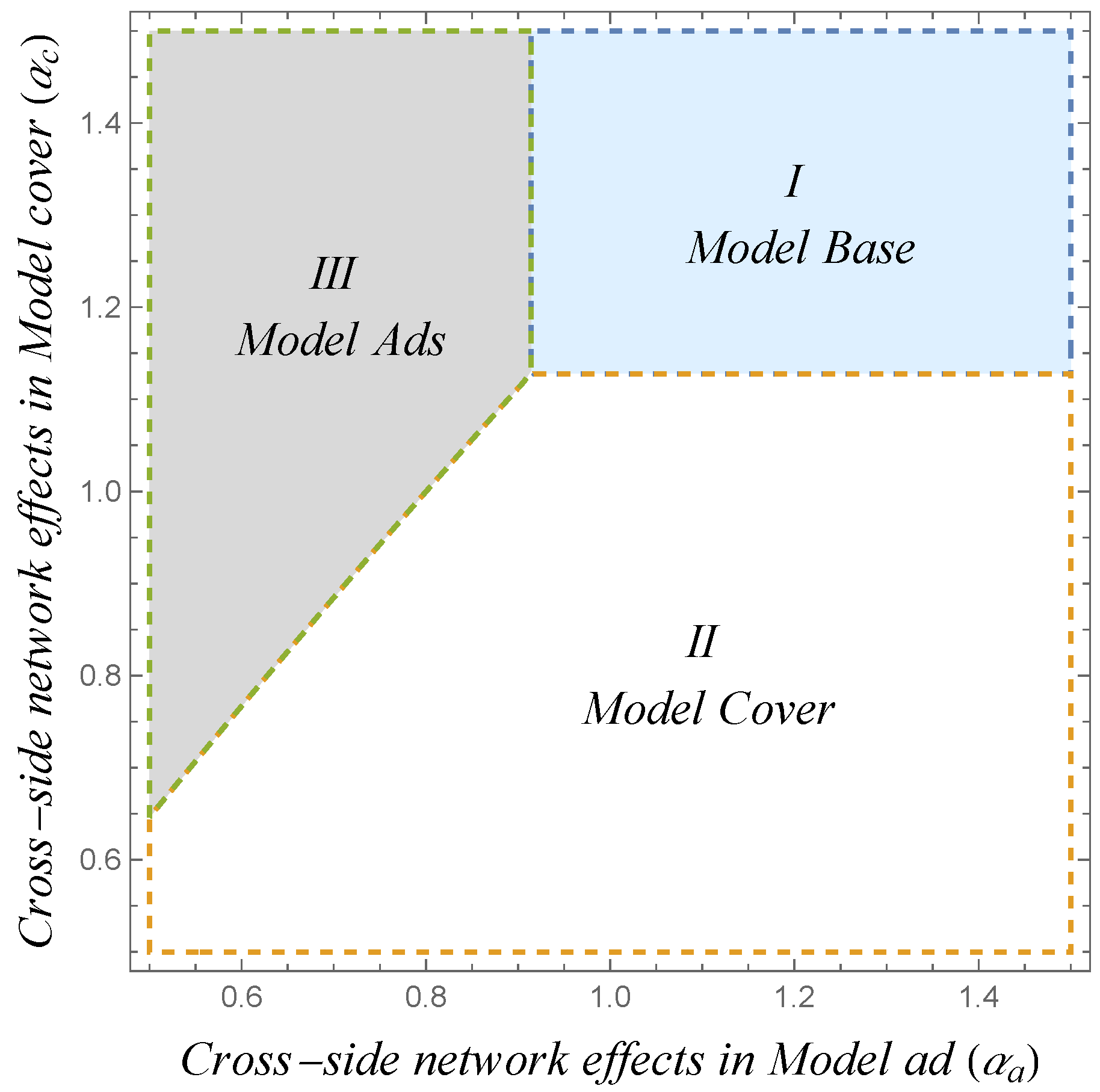

4. Comparative Analysis

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Equalization Strategies for Platforms

- (a)

- In base mode, the platform achieves maximum profit:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

- (b)

- In cover mode, the platform achieves maximum profit:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

- (c)

- In ad mode, the platform achieves maximum profit:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Advertiser Surplus

- (a)

- The surplus of advertisers in base mode is maximized:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

- (b)

- The surplus of advertisers in cover mode is maximized:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

- (c)

- The surplus of advertisers in ad mode is maximized:

- (i)

- When , then ,

- (ii)

- When , then .

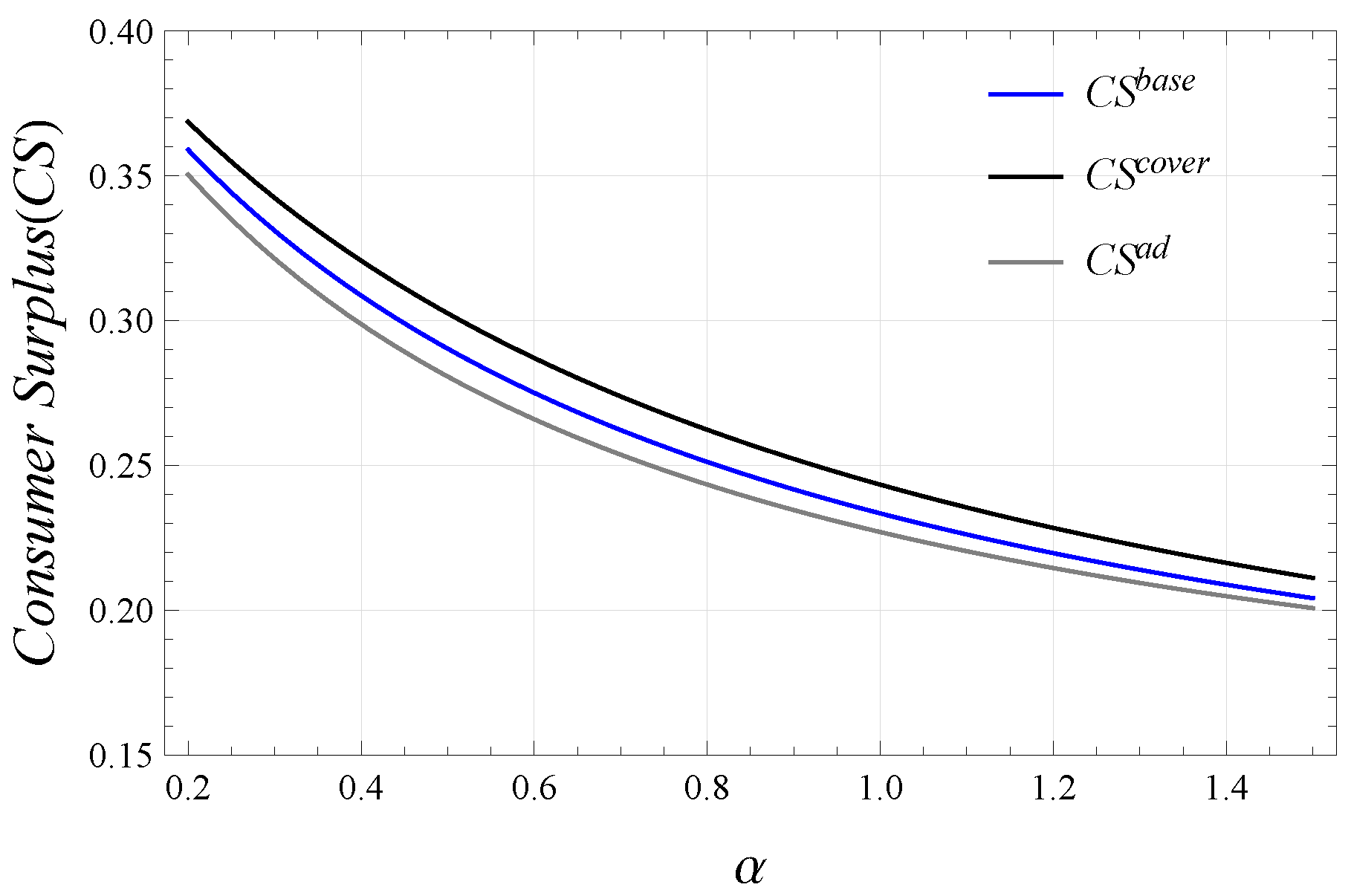

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Consumer Surplus

5. Concluding Remarks and Managerial Implications

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proofs of Lemmas and Corollaries

Appendix A.1. Proof of Lemma 1

Appendix A.2. Proof of Collary 1

- Based on the results in Lemma 1, for the effect of r on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that . . , When , , and vice versa, . , . When , , , and when then the reverse is true.

- Based on the results in Lemma 1, for the effect of on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that . . , When , , and vice versa, . . . When , , , and when then the reverse is true.

- From , we know that , and , therefore .

Appendix A.3. Proof of Lemma 2

Appendix A.4. Proof of Collary 2

- Based on the results in Lemma 2, for the effect of r on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that , , , , .

- Based on the results in Lemma 2, for the effect of on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that , , , , .

Appendix A.5. Proof of Lemma 3

Appendix A.6. Proof of Collary 3

- Based on the results in Lemma 3, for the effect of r on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that . . , when , . , , when , , .

- Based on the results in Lemma 3, for the effect of on the platform’s equilibrium strategy, we can derive that . . , when , . , , when , , .

- From , we know that , and , therefore .

Appendix B. Proofs of Propositions

Appendix B.1. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix B.2. Proof of Proposition 2

Appendix B.3. Proof of Proposition 3

Appendix B.4. Proof of Proposition 4

References

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y. Virtual gifting and danmaku: What motivates people to interact in game live streaming? Telemat. Inform. 2021, 62, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, Q.; Rau, P.L.P. Watching a movie alone yet together: Understanding reasons for watching Danmaku videos. Int. J.-Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2017, 33, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lu, K.; Ausaf, A.; Zhu, M. Constant or inconstant? The time-varying effect of danmaku on user engagement in online video platforms. Internet Res. 2025, 35, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, J.; Wu, P.; Liang, K. Boosting e-commerce sales with live streaming: The power of barrages. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Moscowitz, L.; Wu, L. Online social viewing: Cross-cultural adoption and uses of bullet-screen videos. J. Int. Intercult. Comm. 2020, 13, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Men, J. The impact of Danmu technological features on consumer loyalty intention toward recommendation vlogs: A perspective from social presence and immersion. Inform. Technol. People 2022, 35, 1193–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Wu, J.; Qu, H.; Zeng, Q. Danmaku in the serious live streaming context: The mediating roles of self-determination and cognitive load. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 26, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Li, J. To offer or not to offer? Bullet screen strategies for competing video platforms with vertical differentiation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Sang, Y.; Huang, Y. Danmaku: A new paradigm of social interaction via online videos. ACM Trans. Soc. Comput. 2019, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Huang, M.; Cordie, L. An exploratory study: Using Danmaku in online video-based lectures. Educ. Media Int. 2018, 55, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, A.; Pi, Z.; Yang, J. Danmaku related to video content facilitates learning. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2019, 47, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Pan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S. What motives users to participate in danmu on live streaming platforms? The impact of technical environment and effectance. Data Inf. Manag. 2019, 3, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Sun, T.; Liu, B. Exploring the effect of incorporating danmaku into advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Duan, S.; Li, R. Dynamic advertising insertion strategy with moment-to-moment data using sentiment analysis: The case of danmaku video. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 23, 160–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, R.; Ackerman, P. Motivation and cognitive abilities: An integrative/aptitude-treatment interaction approach to skill acquisition. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 657–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Cothron, S.; Toyama, M. Role of delay discounting in resisting in-class media multitasking under contextual control: A cluster analysis. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2024, 43, 4246–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwark, Y.; Chen, J.; Raghunathan, S. User-generated content and competing firms’ product design. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 4608–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaldoss, W.; Du, J.; Shin, W. Media platforms’ content provision strategies and sources of profits. Market. Sci. 2021, 40, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Coate, S. Market provision of broadcasting: A welfare analysis. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 947–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, K. A two-sided, empirical model of television advertising and viewing markets. Market. Sci. 2008, 27, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampes, C.; Haritchabalet, C.; Jullien, B. Advertising, competition and entry in media industries. J. Ind. Econ. 2009, 57, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, M. Platform competition for advertisers and users in media markets. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2012, 30, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, K.; Srinivasan, K. Freemium as an optimal strategy for market dominant firms. Market. Sci. 2019, 38, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Cooperation among competitors: Some economics of payment card associations. Rand J. Econ. 2002, 33, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Platform competition in two-sided markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2003, 1, 990–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Competition in two-sided markets. Rand J. Econ. 2006, 37, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, D.S.; Rochet, J.C. The pricing of academic journals: A two-sided market perspective. Am. Econ. J. Microeconomics 2010, 2, 222–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, Y.; Katsamakas, E. Design and ownership of two-sided networks: Implications for Internet platforms. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economides, N.; Tåg, J. Network neutrality on the Internet: A two-sided market analysis. Inf. Econ. Policy 2012, 24, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitz, M.; Valletti, T. Content and advertising in the media: Pay-TV versus free-to-air. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2008, 26, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.S. Some empirical aspects of multi-sided platform industries. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2003, 2, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G.; Van Alstyne, M.W. Two-sided network effects: A theory of information product design. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Xu, X.; Bian, Y.; Sun, Y. Optimal trade-in strategy of business-to-consumer platform with dual-format retailing model. Omega 2019, 82, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Kim, B.C.; Park, M.; Straub, D.W. Innovation and policy support for two-sided market platforms: Can government policy makers and executives optimize both societal value and profits? Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 30, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhou, Y.W.; Xie, W.; Zhong, Y.; Cao, B. Pricing and product-bundling strategies for e-commerce platforms with competition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283, 1026–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Xu, T.; Yin, Z.; Liu, D.; Chen, E.; Lv, G.; Li, C. Character-oriented video summarization with visual and textual cues. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 22, 2684–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Guo, Q.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W. Do real-time reviews matter? Examining how bullet screen influences consumers’ purchase intention in live streaming commerce. Inform. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 2051–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroni, E.; Madio, L.; Shekhar, S. Superstar exclusivity in two-sided markets. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 991–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature | Bullet Screen | Pricing | Two-Sided Markets | Main Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wan et al. [5] | ✓ | × | × | Bullet screen effects on attention span |

| Li et al. [14] | ✓ | ✓ | × | Bullet screens’ impact on ad revenues |

| Amaldoss et al. [18] | × | ✓ | ✓ | Comparison of three pricing models |

| Crampes et al. [21] | × | ✓ | × | Advertising in media platforms |

| Zhou et al. [36] | × | ✓ | × | Character-oriented video summarization |

| Zeng et al. [37] | ✓ | × | ✓ | Bullet screen’s influence |

| Carroni et al. [38] | × | ✓ | ✓ | Exclusivity in two-sided markets |

| Present study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Competitive bullet screen strategies |

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Cross-side network effects from advertisers to consumers, | |

| Cross-side network effects from consumers to advertisers | |

| r | Consumer attention on bullet screen, , where |

| Proportion of consumers who prefer bullet screen, | |

| v | Base quality for consumer gets from video content |

| Consumer size, | |

| Number of consumers with bullet screen preferences | |

| Number of consumers resistant to bullet screens | |

| Size of advertisers | |

| Consumer perceived value factor, | |

| f | Cost of advertisers’ preferences, |

| k | Platform’s bullet screen cost factor |

| Decision variables | Description |

| p | Advertising price of platform |

| q | Quality of the bullet screens of the platform |

| Condition | , | , | , | , | , |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | |

| ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↘ | ↘ | |

| ↗ | ↗ | ↘ | ↘ | ↘ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, X.; Li, L. What Does Bullet Screen Bring to Video Platform? A Theoretical Analysis Comparing Different Bullet Screen Modes. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040338

Zhu X, Li L. What Does Bullet Screen Bring to Video Platform? A Theoretical Analysis Comparing Different Bullet Screen Modes. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040338

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Xingzhen, and Li Li. 2025. "What Does Bullet Screen Bring to Video Platform? A Theoretical Analysis Comparing Different Bullet Screen Modes" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040338

APA StyleZhu, X., & Li, L. (2025). What Does Bullet Screen Bring to Video Platform? A Theoretical Analysis Comparing Different Bullet Screen Modes. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040338