The 14-3-3 Protein Family, Beyond the Kinases and Phosphatases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Functional Divergence and Evolutionary Conservation of 14-3-3 Protein Paralogs in Mammals

Evolution of Human 14-3-3 Protein Family

3. A Structural and Functional Journey from the N-Terminal to the C-Terminal Region of 14-3-3 Proteins

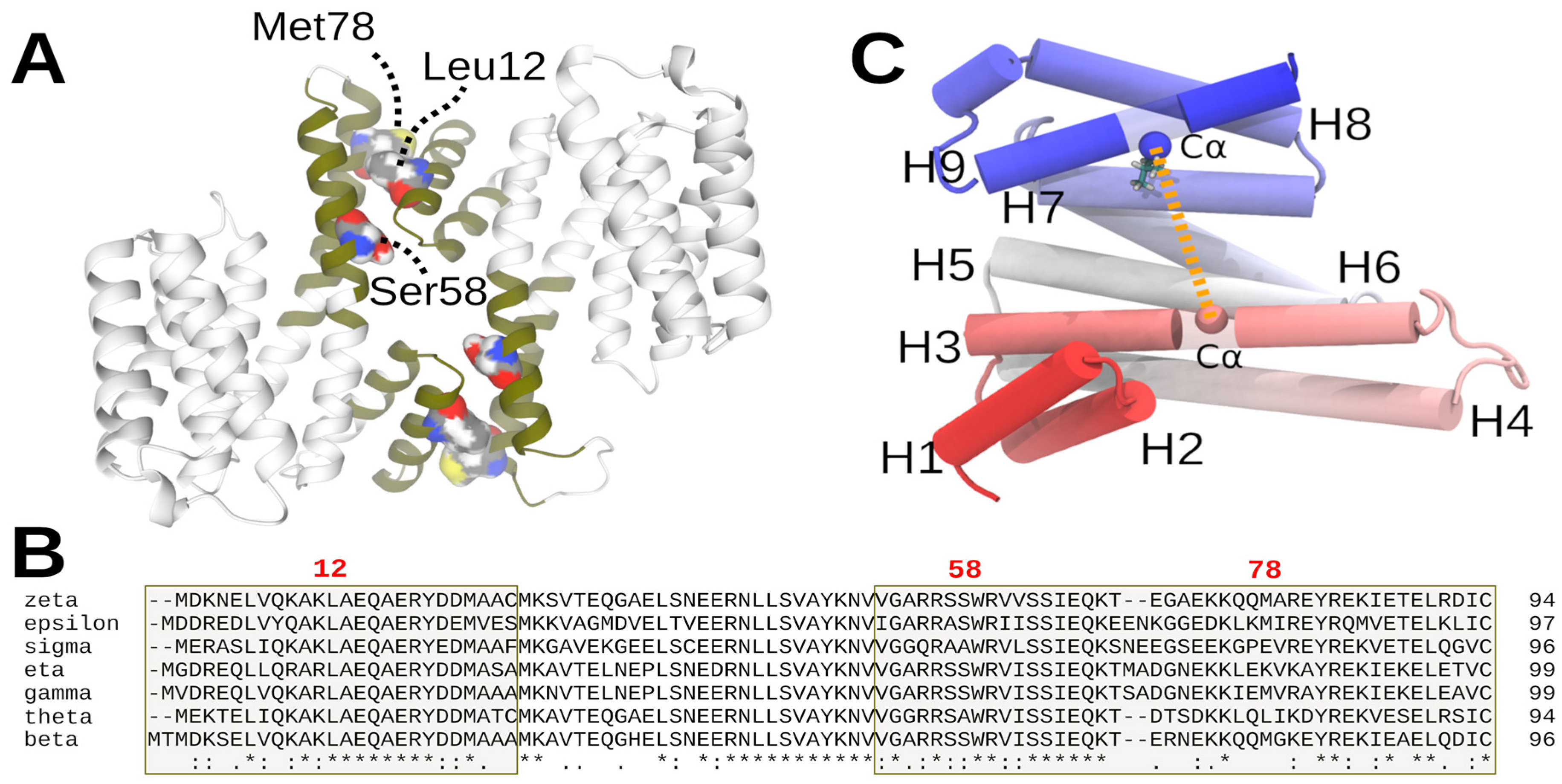

3.1. Alpha-Helices 1 to 4, the Dimeric Interphase

3.2. Alpha-Helices 3, 5, 7, and 9, the Amphipathic Groove

3.3. Alpha-Helices 4 to 9, Secondary Binding Sites

3.4. The Intrinsic Disordered C-Terminal Region

3.5. 14-3-3’s Small Molecule Modulators

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amato, M.E.; Balsells, S.; Martorell, L.; Alcalá San Martín, A.; Ansell, K.; Børresen, M.L.; Johnson, H.; Korff, C.; Garcia-Tarodo, S.; Lefranc, J.; et al. Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 56 due to YWHAG variants: 12 new cases and review of the literature. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2024, 53, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluchanko, N.N.; Bustos, D.M. Intrinsic disorder associated with 14-3-3 proteins and their partners. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 166, 19–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, D.M.; Iglesias, A.A. Intrinsic disorder is a key characteristic in partners that bind 14-3-3 proteins. Proteins 2006, 63, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cao, S.; Ding, G.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, Q.; Feng, J.; Liu, S.; Qin, L.; et al. The role of 14-3-3 proteins in cell signalling pathways and virus infection. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4173–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.W.; Perez, V.J. Specific acidic proteins of the nervous system. In Physiological and Biochemical Aspects of Nervous Integration; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967; pp. 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Uhart, M.; Flores, G.; Bustos, D.M. Controllability of protein-protein interaction phosphorylation-based networks: Participation of the hub 14-3-3 protein family. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, D.M. The role of protein disorder in the 14-3-3 interaction network. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinti, M.; Johnson, C.; Toth, R.; Ferrier, D.E.; Mackintosh, C. Evolution of signal multiplexing by 14-3-3-binding 2R-ohnologue protein families in the vertebrates. Open Biol. 2012, 2, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhart, M.; Bustos, D.M. Human 14-3-3 paralogs differences uncovered by cross-talk of phosphorylation and lysine acetylation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, E.E.; Skrabana, R.; Bustos, D.M. Deciphering opening mechanisms of 14-3-3 proteins. Protein Sci. 2025, 34, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferl, R.J.; Lu, G.; Bowen, B.W. Evolutionary implications of the family of 14-3-3 brain protein homologs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica 1994, 92, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, P.S.; Ramshaw, H.S.; Thomas, P.Q.; Toyo-Oka, K.; Xu, X.; Martin, S.; Coyle, P.; Guthridge, M.A.; Stomski, F.; van den Buuse, M.; et al. Neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric behaviour defects arise from 14-3-3ζ deficiency. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, B.; Toyo-Oka, K. 14-3-3 Proteins in Brain Development: Neurogenesis, Neuronal Migration and Neuromorphogenesis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kanani, F.; Titheradge, H.; Cooper, N.; Elmslie, F.; Lees, M.M.; Juusola, J.; Pisani, L.; McKenna, C.; Mignot, C.; Valence, S.; et al. Expanding the genotype-phenotype correlation of de novo heterozygous missense variants in YWHAG as a cause of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2020, 182, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Song, Z.; Xue, J.; Yang, C.; Li, F.; Pan, H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, H. A heterozygous missense variant in the YWHAG gene causing developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 56 in a Chinese family. BMC Med. Genom. 2022, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Cui, L.; Zeng, Y.; Song, W.; Gaur, U.; Yang, M. 14-3-3 Proteins Are on the Crossroads of Cancer, Aging, and Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torrico, B.; Antón-Galindo, E.; Fernàndez-Castillo, N.; Rojo-Francàs, E.; Ghorbani, S.; Pineda-Cirera, L.; Hervás, A.; Rueda, I.; Moreno, E.; Fullerton, J.M.; et al. Involvement of the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Schizophrenia: Genetics, Transcriptomics and Functional Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navarrete, M.; Zhou, Y. The 14-3-3 Protein Family and Schizophrenia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 857495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.E.; Cho, C.H.; Sim, K.M.; Kwon, O.; Hwang, E.M.; Kim, H.W.; Park, J.Y. 14-3-3γ Haploinsufficient Mice Display Hyperactive and Stress-sensitive Behaviors. Exp. Neurobiol. 2019, 28, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Winter, M.; Rokavec, M.; Hermeking, H. 14-3-3σ Functions as an Intestinal Tumor Suppressor. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 3621–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganne, A.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Mainali, N.; Atluri, P.; Shmookler Reis, R.J.; Ayyadevara, S. Physiological Consequences of Targeting 14-3-3 and Its Interacting Partners in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foote, M.; Zhou, Y. 14-3-3 proteins in neurological disorders. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 3, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.E.; Johnson, J.D. 14-3-3ζ: A numbers game in adipocyte function? Adipocyte 2015, 5, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhart, M.; Bustos, D.M. Protein intrinsic disorder and network connectivity. The case of 14-3-3 proteins. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontini-López, Y.R.; Gojanovich, A.D.; Del Veliz, S.; Uhart, M.; Bustos, D.M. 14-3-3β isoform is specifically acetylated at Lys51 during differentiation to the osteogenic lineage. J. Cell Biochem. 2021, 122, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, K.L.; Chan, T.Y.; Torres, M.P.; Andersen, J.L. The dynamic and stress-adaptive signaling hub of 14-3-3: Emerging mechanisms of regulation and context-dependent protein-protein interactions. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5587–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Fischle, W.; Seiser, C. Modulation of 14-3-3 interaction with phosphorylated histone H3 by combinatorial modification patterns. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeytuni, N.; Zarivach, R. Structural and functional discussion of the tetra-trico-peptide repeat, a protein interaction module. Structure 2012, 20, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Smerdon, S.J.; Jones, D.H.; Dodson, G.G.; Soneji, Y.; Aitken, A.; Gamblin, S.J. Structure of a 14-3-3 protein and implications for coordination of multiple signalling pathways. Nature 1995, 376, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bienkowska, J.; Petosa, C.; Collier, R.J.; Fu, H.; Liddington, R. Crystal structure of the zeta isoform of the 14-3-3 protein. Nature 1995, 376, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier, C.C.; Ottmann, C.; Perry, M.W.D. 14-3-3 modulation of the inflammatory response. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J.M.; Goodwin, K.L.; Sandow, J.J.; Coolen, C.; Perugini, M.A.; Webb, A.I.; Pitson, S.M.; Lopez, A.F.; Carver, J.A. Role of salt bridges in the dimer interface of 14-3-3ζ in dimer dynamics, N-terminal α-helical order, and molecular chaperone activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J.M.; Murphy, J.; Stomski, F.C.; Berndt, M.C.; Lopez, A.F. The dimeric versus monomeric status of 14-3-3zeta is controlled by phosphorylation of Ser58 at the dimer interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36323–36327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trošanová, Z.; Louša, P.; Kozeleková, A.; Brom, T.; Gašparik, N.; Tungli, J.; Weisová, V.; Župa, E.; Žoldák, G.; Hritz, J. Quantitation of Human 14-3-3ζ Dimerization and the Effect of Phosphorylation on Dimer-monomer Equilibria. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandova, Z.; Trosanova, Z.; Weisova, V.; Oostenbrink, C.; Hritz, J. Free energy calculations on the stability of the 14-3-3ζ protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2018, 1866, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.M.; Jin, Y.H.; Choi, J.K.; Baek, K.H.; Yeo, C.Y.; Lee, K.Y. Protein kinase A phosphorylates and regulates dimerization of 14-3-3 epsilon. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shao, Z.; Kerkela, R.; Ichijo, H.; Muslin, A.J.; Pombo, C.; Force, T. Serine 58 of 14-3-3zeta is a molecular switch regulating ASK1 and oxidant stress-induced cell death. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 4167–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, D.W.; Rane, M.J.; Chen, Q.; Singh, S.; McLeish, K.R. Identification of 14-3-3zeta as a protein kinase B/Akt substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21639–21642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Stanisheuski, S.; Franklin, R.; Vogel, A.; Vesely, C.H.; Reardon, P.; Sluchanko, N.N.; Beckman, J.S.; Karplus, P.A.; Mehl, R.A.; et al. Autonomous Synthesis of Functional, Permanently Phosphorylated Proteins for Defining the Interactome of Monomeric 14-3-3ζ. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 816–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilker, E.W.; Grant, R.A.; Artim, S.C.; Yaffe, M.B. A structural basis for 14-3-3sigma functional specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18891–18898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoodt, B.; Benzinger, A.; Popowicz, G.M.; Holak, T.A.; Hermeking, H. Characterization of 14-3-3sigma dimerization determinants: Requirement of homodimerization for inhibition of cell proliferation. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluchanko, N.N.; Tugaeva, K.V.; Greive, S.J.; Antson, A.A. Chimeric 14-3-3 proteins for unraveling interactions with intrinsically disordered partners. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.C.; Jelinek, T.; Zhang, L.; Ruoslahti, E.; Fu, H. Isolation of high-affinity peptide antagonists of 14-3-3 proteins by phage display. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 12499–12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, S.C.; Pederson, K.J.; Zhang, L.; Barbieri, J.T.; Fu, H. Interaction of 14-3-3 with a nonphosphorylated protein ligand, exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 5216–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somsen, B.A.; Cossar, P.J.; Arkin, M.R.; Brunsveld, L.; Ottmann, C. 14-3-3 Protein-Protein Interactions: From Mechanistic Understanding to Their Small-Molecule Stabilization. Chembiochem 2024, 25, e202400214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obsilova, V.; Obsil, T. Structural insights into the functional roles of 14-3-3 proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1016071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lee, W.H.; Sobott, F.; Papagrigoriou, E.; Robinson, C.V.; Grossmann, J.G.; Sundström, M.; Doyle, D.A.; Elkins, J.M. Structural basis for protein-protein interactions in the 14-3-3 protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17237–17242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, H.; Liu, J.Y.; Wang, J. Insight into conformational change for 14-3-3σ protein by molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 2794–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Oostenbrink, C.; Hritz, J. Exploring the binding pathways of the 14-3-3ζ protein: Structural and free-energy profiles revealed by Hamiltonian replica exchange molecular dynamics with distancefield distance restraints. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torosyan, H.; Paul, M.D.; Forget, A.; Lo, M.; Diwanji, D.; Pawłowski, K.; Krogan, N.J.; Jura, N.; Verba, K.A. Structural insights into regulation of the PEAK3 pseudokinase scaffold by 14-3-3. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Rawson, S.; Li, K.; Kim, B.W.; Ficarro, S.B.; Pino, G.G.; Sharif, H.; Marto, J.A.; Jeon, H.; Eck, M.J. Architecture of autoinhibited and active BRAF-MEK1-14-3-3 complexes. Nature 2019, 575, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Fiesco, J.A.; Beilina, A.; Alvarez de la Cruz, A.; Li, N.; Metcalfe, R.D.; Cookson, M.R.; Zhang, P. 14-3-3 binding maintains the Parkinson’s associated kinase LRRK2 in an inactive state. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obsilova, V.; Herman, P.; Vecer, J.; Sulc, M.; Teisinger, J.; Obsil, T. 14-3-3zeta C-terminal stretch changes its conformation upon ligand binding and phosphorylation at Thr232. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 4531–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silhan, J.; Obsilova, V.; Vecer, J.; Herman, P.; Sulc, M.; Teisinger, J.; Obsil, T. 14-3-3 protein C-terminal stretch occupies ligand binding groove and is displaced by phosphopeptide binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49113–49119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluchanko, N.N.; Beelen, S.; Kulikova, A.A.; Weeks, S.D.; Antson, A.A.; Gusev, N.B.; Strelkov, S.V. Structural Basis for the Interaction of a Human Small Heat Shock Protein with the 14-3-3 Universal Signaling Regulator. Structure 2017, 25, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, A.B.; Masters, S.C.; Yang, H.; Fu, H. Role of the 14-3-3 C-terminal loop in ligand interaction. Proteins 2002, 49, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, M.; Grad, J.N.; Mittal, S.; Bier, D.; Mertel, M.; Ohl, L.; Bartel, M.; Briels, J.; Heimann, M.; Ottmann, C.; et al. Rational Design, Binding Studies, and Crystal-Structure Evaluation of the First Ligand Targeting the Dimerization Interface of the 14-3-3ζ Adapter Protein. Chembiochem 2018, 19, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, H.J.; Riemens, R.; Thee, S.; Beishuizen, B.; da Costa Pereira, D.; Wijtmans, M.; de Esch, I.; Smit, M.J.; de Boer, A.H. Fragment Screening Yields a Small-Molecule Stabilizer of 14-3-3 Dimers That Modulates Client Protein Interactions. Chembiochem 2022, 23, e202200178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iralde-Lorente, L.; Tassone, G.; Clementi, L.; Franci, L.; Munier, C.C.; Cau, Y.; Mori, M.; Chiariello, M.; Angelucci, A.; Perry, M.W.D.; et al. Identification of Phosphate-Containing Compounds as New Inhibitors of 14-3-3/c-Abl Protein-Protein Interaction. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, P.; Röglin, L.; Meissner, N.; Hennig, S.; Kohlbacher, O.; Ottmann, C. Virtual screening and experimental validation reveal novel small-molecule inhibitors of 14-3-3 protein-protein interactions. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 8468–8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Bier, D.; Guillory, X.; Briels, J.; Ruiz-Blanco, Y.B.; Sanchez-Garcia, E.; Ottmann, C.; Kaiser, M. Mono- and Bivalent 14-3-3 Inhibitors for Characterizing Supramolecular “Lysine Wrapping” of Oligoethylene Glycol (OEG) Moieties in Proteins. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 13807–13814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, S.A.; Meijer, F.A.; Neves, J.F.; Brunsveld, L.; Landrieu, I.; Ottmann, C.; Milroy, L.G. Inhibition of 14-3-3/Tau by Hybrid Small-Molecule Peptides Operating via Two Different Binding Modes. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2639–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, P.; Kjær, S.; Garg, R.; Purkiss, A.; George, R.; Cain, R.J.; Bineva, G.; Reymond, N.; McColl, B.; Thompson, A.J.; et al. 14-3-3 proteins interact with a hybrid prenyl-phosphorylation motif to inhibit G proteins. Cell 2013, 153, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, L.G.; Bartel, M.; Henen, M.A.; Leysen, S.; Adriaans, J.M.; Brunsveld, L.; Landrieu, I.; Ottmann, C. Stabilizer-Guided Inhibition of Protein-Protein Interactions. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed. Engl.) 2015, 54, 15720–15724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillory, X.; Hadrović, I.; de Vink, P.J.; Sowislok, A.; Brunsveld, L.; Schrader, T.; Ottmann, C. Supramolecular Enhancement of a Natural 14-3-3 Protein Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13495–13500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T.; Shimazaki, K. Analysis of the phosphorylation level in guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase in response to fusicoccin. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, C.; Higuchi, Y.; Koschinsky, K.; Bartel, M.; Schumacher, B.; Thiel, P.; Nitta, H.; Preisig-Müller, R.; Schlichthörl, G.; Renigunta, V.; et al. A semisynthetic fusicoccane stabilizes a protein-protein interaction and enhances the expression of K+ channels at the cell surface. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bier, D.; Rose, R.; Bravo-Rodriguez, K.; Bartel, M.; Ramirez-Anguita, J.M.; Dutt, S.; Wilch, C.; Klärner, F.G.; Sanchez-Garcia, E.; Schrader, T.; et al. Molecular tweezers modulate 14-3-3 protein-protein interactions. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossar, P.J.; Wolter, M.; van Dijck, L.; Valenti, D.; Levy, L.M.; Ottmann, C.; Brunsveld, L. Reversible Covalent Imine-Tethering for Selective Stabilization of 14-3-3 Hub Protein Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 8454–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Molzan, M.; Weyand, M.; Rose, R.; Ottmann, C. Structural insights of the MLF1/14-3-3 interaction. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andlovic, B.; Valenti, D.; Centorrino, F.; Picarazzi, F.; Hristeva, S.; Hiltmann, M.; Wolf, A.; Cantrelle, F.X.; Mori, M.; Landrieu, I.; et al. Fragment-Based Interrogation of the 14-3-3/TAZ Protein-Protein Interaction. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 2196–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, E.; Skora, L.; Leysen, S.; Brunsveld, L.; Koch, U.; Nussbaumer, P.; Jahnke, W.; Ottmann, C. Identification of Two Secondary Ligand Binding Sites in 14-3-3 Proteins Using Fragment Screening. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3972–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Often Recognized by 14-3-3. Y/N | Consensus Phosphorylation Motif | Notes/Function | Representative Kinases | Kinase Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | RXXS/T or RXRXXS/T | Ser/Thr phosphorylation | PKA, PKG, PKC, Akt/PKB | AGC |

| Y | S/TP | Proline-directed Ser/Thr kinases; regulate cell cycle and signalling | CDKs, MAPKs, GSK3 | CMGC |

| Decrease affinity of binding—N | D/E XXS/T(p) | Often requires pre-phosphorylated substrate (p) | CK1α, CK1δ | CK1 |

| N | S/TD/E X D/E | Acidophilic; targets negative residues near Ser/Thr | CK2α | CK2 |

| Y (Inhibition of binding) | S/T XXS/T | Often upstream in MAPK cascades | MEKK1, ASK1 | STE (MAPKKK family) |

| Y | RXXS/T | Activated by Ca2+/calmodulin; Ser/Thr phosphorylation | CaMKII, AMPK | CAMK |

| N | S/TQ | DNA damage or nutrient response signalling | mTOR, ATM, ATR | Atypical |

| variable | S/Ta | Diverse motifs; context-dependent | Various | Other Ser/Thr |

| Key References | Human Disease Associations | Knockout/Loss-of-Function Phenotype | Chromosome (Human) | Paralog (Human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16,17] | Linked to neuropsychiatric disorders; expression altered in cancers | Full KO is embryonic lethal; partial reduction produces context-dependent phenotypes | 7q11.23 | YWHAB/(β) |

| [17,18] | De novo LoF variants cause neurodevelopmental syndromes | KO or conditional KO causes severe neurodevelopmental abnormalities; essential for neuronal migration; male infertility in mice | 17p13.3 | YWHAE/(ε) |

| [17,19] | Associated with schizophrenia and autism | Haploinsufficiency causes hyperactivity, anxiety-related behaviour, and neuronal signalling alterations | 7q11.23 | YWHAG/(γ) |

| [16,18] | Associated with Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia | Single KO usually mild due to redundancy; combined loss with other paralogs causes synaptic and behavioural defects | 22q13.2 | YWHAH/(η) |

| [20] | Colorectal cancer and association with metastasis and poor survival of patients | KO increases susceptibility to colorrectal cancer | 1p36.11 | SFN/(σ) |

| [16] | Expression altered in Alzheimer’s disease and multiple cancers | KO produces mild neurological traits; strong functional redundancy with β/ε/ζ | 22q13.1 | YWHAQ/(θ) |

| [21,22] | Linked to schizophrenia, CJD, Alzheimer’s, cancers | KO or KD causes neuronal migration defects, cognitive impairment, altered spine density, hyperactivity | 8q22.3 | YWHAZ/(ζ) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrera, E.E.; Uhart, M.; Bustos, D.M. The 14-3-3 Protein Family, Beyond the Kinases and Phosphatases. Kinases Phosphatases 2025, 3, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040024

Barrera EE, Uhart M, Bustos DM. The 14-3-3 Protein Family, Beyond the Kinases and Phosphatases. Kinases and Phosphatases. 2025; 3(4):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrera, Exequiel E., Marina Uhart, and Diego M. Bustos. 2025. "The 14-3-3 Protein Family, Beyond the Kinases and Phosphatases" Kinases and Phosphatases 3, no. 4: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040024

APA StyleBarrera, E. E., Uhart, M., & Bustos, D. M. (2025). The 14-3-3 Protein Family, Beyond the Kinases and Phosphatases. Kinases and Phosphatases, 3(4), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040024