Bioinformatic Investigation of Regulatory Elements in the Core Promoters of CK2 Genes and Pseudogene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

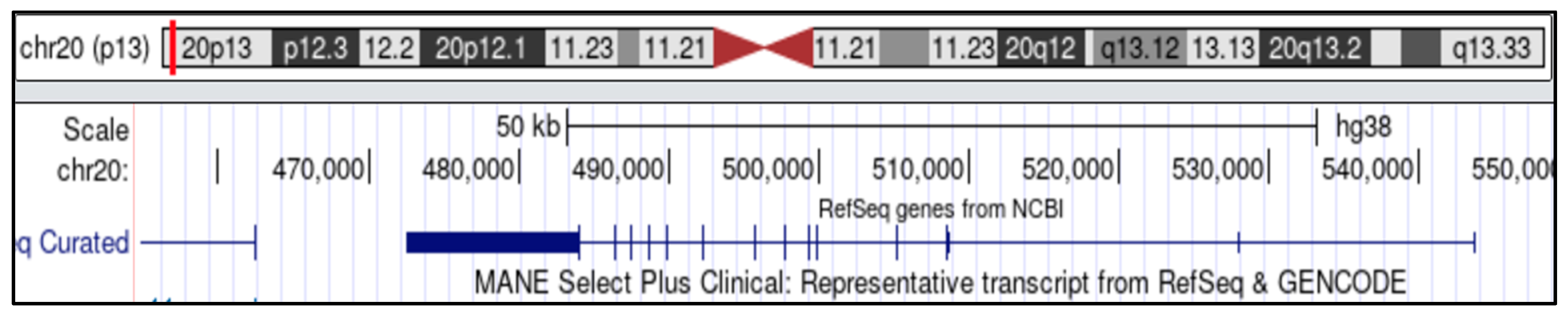

2.1. Human CK2 Gene Structure

2.2. Transcriptional Start Region (TSR) Instead of Transcription Start Site (TSS)

2.2.1. FANTOM5 Results

2.2.2. DataBase of Transcriptional Start Sites (DBTSS) Results

2.2.3. TSS Utilization in FANTOM5 Human Time Course Experiments

2.3. CK2 Gene and Pseudogene Core Promoter Elements

2.3.1. Canonical and Non-Canonical Initiator (Inr) Elements

2.3.2. DCE Core Promoter Sequences Are Common in CK2 Genes and Pseudogene

2.3.3. DPEs in Wnt/β-Catenin-Signaling Components

2.3.4. Pause Button Core Promoter Sequences Found in CSNK2A1, CSNK2A2, and CSNK2B

2.3.5. Presence of Core Promoter Elements Among Mammalian Species

3. Discussion

3.1. Broad Promoters

3.2. Time Course Experiments

3.3. Initiator Elements

3.4. Core Promoter Elements

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Analysis and Figures

4.2. FANTOM5

4.3. DBTSS

4.4. Mammalian Core Promoter Sequence Alignments

4.5. Core Promoter Element Identification

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- St-Denis, N.A.; Litchfield, D.W. Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: From birth to death: The role of protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1817–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzzene, M.; Pinna, L.A. Addiction to protein kinase CK2: A common denominator of diverse cancer cells? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010, 1804, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, C.V. On the physiological role of casein kinase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 1998, 59, 95–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buchou, T.; Vernet, M.; Blond, O.; Jensen, H.H.; Pointu, H.; Olsen, B.B.; Cochet, C.; Issinger, O.-G.; Boldyreff, B. Disruption of the Regulatory β Subunit of Protein Kinase CK2 in Mice Leads to a Cell-Autonomous Defect and Early Embryonic Lethality. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Toselli, P.A.; Russell, L.D.; Seldin, D.C. Globozoospermia in mice lacking the casein kinase II alpha’ catalytic subunit. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, I.; Mizuno, J.; Wu, H.; Imbrie, G.A.; Symes, K.; Seldin, D.C. A role for CK2alpha/beta in Xenopus early embryonic development. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 274, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L.M.; Revuelta-Cervantes, J.; Dominguez, I. CK2 in Embryonic Development. In Protein Kinase CK2; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 129–168. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118482490.ch4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Trembley, J.H.; Wu, J.; Unger, G.M.; Kren, B.T.; Ahmed, K. CK2 Suppression of Apoptosis and Its Implication in Cancer Biology and Therapy; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2013; pp. 219–343. [Google Scholar]

- Seldin, D.C.; Landesman-Bollag, E. The Oncogenic Potential of CK2; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, I.; Sonenshein, G.E.; Seldin, D.C. CK2 and its role in Wnt and NF-κB signaling: Linking development and cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1850–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.M.J.; Lee, M.; Dominguez, I. Cancer-type dependent expression of CK2 transcripts. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, L.A. Protein kinase CK2: A challenge to canons. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115 Pt 20, 3873–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Wu, J.L.; Padmanabha, R.; Glover, C.V. Isolation, sequencing, and disruption of the CKA1 gene encoding the alpha subunit of yeast casein kinase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8, 4981–4990. [Google Scholar]

- Boldyreff, B.; Issinger, O.G. Structure of the gene encoding the murine protein kinase CK2 beta subunit. Genomics 1995, 29, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.; Rubin, C.S. Casein kinase II from Caenorhabditis elegans. Cloning, characterization, and developmental regulation of the gene encoding the beta subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 19796–19802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ole-MoiYoi, O.K.; Sugimoto, C.; Conrad, P.A.; Macklin, M.D. Cloning and characterization of the casein kinase II alpha subunit gene from the lymphocyte-transforming intracellular protozoan parasite Theileria parva. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 6193–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabha, R.; Chen-Wu, J.L.; Hanna, D.E.; Glover, C.V. Isolation, sequencing, and disruption of the yeast CKA2 gene: Casein kinase II is essential for viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990, 10, 4089–4099. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, H.; Wirkner, U.; Jakobi, R.; Hewitt, N.; Schwager, C.; Zimmermann, J.; Ansorge, W.; Pyerin, W. Structure of the gene encoding human casein kinase II subunit beta. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 13706–13711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobi, R.; Voss, H.; Pyerin, W. Human phosvitin/casein kinase type II. Molecular cloning and sequencing of full-length cDNA encoding subunit beta. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989, 183, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krehan, A.; Ansuini, H.; Bocher, O.; Grein, S.; Wirkner, U.; Pyerin, W. Transcription factors ets1, NF-kappa B, and Sp1 are major determinants of the promoter activity of the human protein kinase CK2alpha gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 18327–18336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krehan, A.; Schmalzbauer, R.; Böcher, O.; Ackermann, K.; Wirkner, U.; Brouwers, S.; Pyerin, W. Ets1 is a common element in directing transcription of the alpha and beta genes of human protein kinase CK2. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 3243–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyerin, W.; Ackermann, K. Transcriptional coordination of the genes encoding catalytic (CK2alpha) and regulatory (CK2beta) subunits of human protein kinase CK2. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 227, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, V.; Neckelman, G.; Allende, J.E.; Allende, C.C. The genomic structure of two protein kinase CK2alpha genes of Xenopus laevis and features of the putative promoter region. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 227, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkner, U.; Voss, H.; Ansorge, W.; Pyerin, W. Genomic organization and promoter identification of the human protein kinase CK2 catalytic subunit alpha (CSNK2A1). Genomics 1998, 48, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, N.D.; Ren, B. Finding distal regulatory elements in the human genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009, 19, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, K.; Neidhart, T.; Gerber, J.; Waxmann, A.; Pyerin, W. The catalytic subunit alpha’ gene of human protein kinase CK2 (CSNK2A2): Genomic organization, promoter identification and determination of Ets1 as a key regulator. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 274, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbrie, G.A.; Wilson, N.G.; Seldin, D.C.; Dominguez, I. Regulation of Mouse CK2α (Csnk2a1) Promoter Expression In Vitro and in Cell Lines. Kinases Phosphatases 2025, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, A.C.; Taatjes, D.J. Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archuleta, S.R.; Goodrich, J.A.; Kugel, J.F. Mechanisms and Functions of the RNA Polymerase II General Transcription Machinery during the Transcription Cycle. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carninci, P.; Sandelin, A.; Lenhard, B.; Katayama, S.; Shimokawa, K.; Ponjavic, J.; Semple, C.A.M.; Taylor, M.S.; G, P.G.E.; Frith, M.C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of mammalian promoter architecture and evolution. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 626–635, Erratum in Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louder, R.K.; He, Y.; López-Blanco, J.R.; Fang, J.; Chacón, P.; Nogales, E. Structure of promoter-bound TFIID and model of human pre-initiation complex assembly. Nature 2016, 531, 604–609, Erratum in Nature 2016, 536, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, K.; Ohyama, T. Physical Peculiarity of Two Sites in Human Promoters: Universality and Diverse Usage in Gene Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo Ngoc, L.; Cassidy, C.J.; Huang, C.Y.; Duttke, S.H.C.; Kadonaga, J.T. The human initiator is a distinct and abundant element that is precisely positioned in focused core promoters. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, C.; Hadzhiev, Y.; Balwierz, P.; Tarifeño-Saldivia, E.; Cardenas, R.; Wragg, J.W.; Suzuki, A.-M.; Carninci, P.; Peers, B.; Lenhard, B.; et al. Dual-initiation promoters with intertwined canonical and TCT/TOP transcription start sites diversify transcript processing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyuhas, O.; Kahan, T. The race to decipher the top secrets of TOP mRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Gene Regul. Mech. 2015, 1849, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Edlind, M.P.; Ingolia, N.T.; Janes, M.R.; Sher, A.; Shi, E.Y.; Stumpf, C.R.; Christensen, C.; Bonham, M.J.; et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature 2012, 485, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoreen, C.C.; Chantranupong, L.; Keys, H.R.; Wang, T.; Gray, N.S.; Sabatini, D.M. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature 2012, 485, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.A.; Kim, T.K.; Orkin, S.H. A downstream element in the human β-globin promoter: Evidence of extended sequence-specific transcription factor IID contacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7172–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Gershenzon, N.; Gupta, M.; Ioshikhes, I.P.; Reinberg, D.; Lewis, B.A. Functional Characterization of Core Promoter Elements: The Downstream Core Element Is Recognized by TAF1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9674–9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.L.; Singer, D.S. Core Promoters in Transcription: Old Problem, New Insights. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadonaga, J.T. The DPE, a core promoter element for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Exp. Mol. Med. 2002, 34, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Juven-Gershon, T.; Kadonaga, J.T. Regulation of Gene Expression via the Core Promoter and the Basal Transcriptional Machinery. Dev. Biol. 2010, 339, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, L.; Adelman, K. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: A nexus of gene regulation. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 960–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajos, M.; Jasnovidova, O.; van Bömmel, A.; Freier, S.; Vingron, M.; Mayer, A. Conserved DNA sequence features underlie pervasive RNA polymerase pausing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 4402–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, D.A.; Hong, J.W.; Zeitlinger, J.; Rokhsar, D.S.; Levine, M.S. Promoter elements associated with RNA Pol II stalling in the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7762–7767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gressel, S.; Schwalb, B.; Decker, T.M.; Qin, W.; Leonhardt, H.; Eick, D.; Cramer, P. CDK9-dependent RNA polymerase II pausing controls transcription initiation. eLife 2017, 6, e29736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.A.; Burdick, J.; Daigneault, J.; Zhu, Z.; Grunseich, C.; Bruzel, A.; Cheung, V.G. cis Elements that Mediate RNA Polymerase II Pausing Regulate Human Gene Expression. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 105, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkner, U.; Voss, H.; Lichter, P.; Pyerin, W. Human protein kinase CK2 genes. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 1994, 40, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizio, M.; Harshbarger, J.; Shimoji, H.; Severin, J.; Kasukawa, T.; Sahin, S.; Abugessaisa, I.; Fukuda, S.; Hori, F.; Ishikawa-Kato, S.; et al. Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, S.; Arakawa, T.; Fukuda, S.; Furuno, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Hori, F.; Ishikawa-Kato, S.; Kaida, K.; Kaiho, A.; Kanamori-Katayama, M.; et al. FANTOM5 CAGE profiles of human and mouse samples. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Kawano, S.; Mitsuyama, T.; Suyama, M.; Kanai, Y.; Shirahige, K.; Sasaki, H.; Tokunaga, K.; Tsuchihara, K.; Sugano, S.; et al. DBTSS/DBKERO for integrated analysis of transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D229–D238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, A.R.R.; Kawaji, H.; Rehli, M.; Kenneth Baillie, J.; de Hoon, M.J.L.; Haberle, V.; Lassmann, T.; Kulakovskiy, I.V.; Lizio, M.; Itoh, M.; et al. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature 2014, 507, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policastro, R.A.; Zentner, G.E. Global approaches for profiling transcription initiation. Cell Rep. Methods 2021, 1, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberle, V.; Li, N.; Hadzhiev, Y.; Plessy, C.; Previti, C.; Nepal, C.; Gehrig, J.; Dong, X.; Akalin, A.; Suzuki, A.M.; et al. Two independent transcription initiation codes overlap on vertebrate core promoters. Nature 2014, 507, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danks, G.B.; Navratilova, P.; Lenhard, B.; Thompson, E.M. Distinct core promoter codes drive transcription initiation at key developmental transitions in a marine chordate. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; Van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Dimont, E.; Ha, T.; Swanson, D.J.; Consortium, F.; Hide, W.; Goldowitz, D. Relatively frequent switching of transcription start sites during cerebellar development. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 461, Erratum in BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robitzki, A.; Bodenbach, L.; Voss, H.; Pyerin, W. Human casein kinase II. The subunit alpha protein activates transcription of the subunit beta gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 5694–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Bolotin, E.; Jiang, T.; Sladek, F.M.; Martinez, E. Prevalence of the Initiator over the TATA box in human and yeast genes and identification of DNA motifs enriched in human TATA-less core promoters. Gene 2007, 389, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberle, V.; Stark, A. Eukaryotic core promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloutskin, A.; Shir-Shapira, H.; Freiman, R.N.; Juven-Gershon, T. The Core Promoter Is a Regulatory Hub for Developmental Gene Expression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 666508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehavi, Y.; Sloutskin, A.; Kuznetsov, O.; Juven-Gershon, T. The core promoter composition establishes a new dimension in developmental gene networks. Nucleus 2014, 5, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, I.; Mizuno, J.; Wu, H.; Song, D.H.; Symes, K.; Seldin, D.C. Protein kinase CK2 is required for dorsal axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 2004, 274, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. The Clustal Omega Multiple Alignment Package. In Multiple Sequence Alignment; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2231, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rach, E.A.; Yuan, H.Y.; Majoros, W.H.; Tomancak, P.; Ohler, U. Motif composition, conservation and condition-specificity of single and alternative transcription start sites in the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bai, L.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Sun, J.; Shao, Z. Selective translational usage of TSS and core promoters revealed by translatome sequencing. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsson, H.; Salvatore, M.; Vaagensø, C.; Alcaraz, N.; Bornholdt, J.; Rennie, S.; Andersson, R. Promoter sequence and architecture determine expression variability and confer robustness to genetic variants. eLife 2022, 11, e80943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitz, M.J.; Calhoun, P.J.; James, C.C.; Taetzsch, T.; George, K.K.; Robel, S.; Valdez, G.; Smyth, J.W. Dynamic UTR Usage Regulates Alternative Translation to Modulate Gap Junction Formation during Stress and Aging. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 2737–2747.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibby, A.C.; Litchfield, D.W. The Multiple Personalities of the Regulatory Subunit of Protein Kinase CK2: CK2 Dependent and CK2 Independent Roles Reveal a Secret Identity for CK2β. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2005, 1, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenarh, M.; Götz, C. Protein Kinase CK2α’, More than a Backup of CK2α. Cells 2023, 12, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Wakaguri, H.; Sugano, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakai, K. DBTSS provides a tissue specific dynamic view of Transcription Start Sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D98–D104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, P.R.; Yoon, K.; Ko, D.; Smith, A.D.; Qiao, M.; Suresh, U.; Burns, S.C.; Penalva, L.O.F. Before It Gets Started: Regulating Translation at the 5′ UTR. Comp. Funct. Genom. 2012, 2012, 475731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Gilbert, W.V. Alternative transcription start site selection leads to large differences in translation activity in yeast. RNA 2012, 18, 2299–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkley, G.E.; Verrijzer, C.P. DNA binding site selection by RNA polymerase II TAFs: A TAF(II)250-TAF(II)150 complex recognizes the initiator. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 4835–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstoeger, T.; Papasaikas, P.; Piskadlo, E.; Chao, J.A. Distinct roles of LARP1 and 4EBP1/2 in regulating translation and stability of 5′TOP mRNAs. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, H.B.; Fumagalli, S.; Dennis, P.B.; Reinhard, C.; Pearson, R.B.; Thomas, G. Rapamycin suppresses 5′TOP mRNA translation through inhibition of p70s6k. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3693–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, L.; van den Elzen, A.M.G.; Watson, M.J.; Thoreen, C.C. Global analysis of LARP1 translation targets reveals tunable and dynamic features of 5′ TOP motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 5319–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abazari, N.; Beghini, A. CSNK2A2 (Casein kinase 2 alpha 2). Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 2020. Available online: https://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/gene/40171/csnk2a2-%28casein-kinase-2-alpha-2%29 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Strum, S.W.; Gyenis, L.; Litchfield, D.W. CSNK2 in cancer: Pathophysiology and translational applications. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Peng, L.R.; Yu, A.Q.; Li, J. CSNK2A2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through activation of NF-κB pathway. Ann. Hepatol. 2023, 28, 101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.E.; Seidner, Y.; Dominguez, I. Mining CK2 in cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115609, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Du, Q.; Wang, W. CSNK2A1 Promotes Gastric Cancer Invasion Through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR Signaling Pathway. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 10135–10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Hu, Q.; Fan, K.; Yang, C.; Gao, Y. CSNK2B contributes to colorectal cancer cell proliferation by activating the mTOR signaling. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 15, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anish, R.; Hossain, M.B.; Jacobson, R.H.; Takada, S. Characterization of Transcription from TATA-Less Promoters: Identification of a New Core Promoter Element XCPE2 and Analysis of Factor Requirements. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, S.; Gumhold, C.; Ampofo, E.; Montenarh, M.; Rother, K. CK2 kinase activity but not its binding to CK2 promoter regions is implicated in the regulation of CK2α and CK2β gene expressions. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 384, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tokusumi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Song, X.; Jacobson, R.H.; Takada, S. The New Core Promoter Element XCPE1 (X Core Promoter Element 1) Directs Activator-, Mediator-, and TATA-Binding Protein-Dependent but TFIID-Independent RNA Polymerase II Transcription from TATA-Less Promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 1844–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.A.; Sims, R.J.; Lane, W.S.; Reinberg, D. Functional characterization of core promoter elements: DPE-specific transcription requires the protein kinase CK2 and the PC4 coactivator. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Barrera, L.O.; Zheng, M.; Qu, C.; Singer, M.A.; Richmond, T.A.; Wu, Y.; Green, R.D.; Ren, B. A high-resolution map of active promoters in the human genome. Nature 2005, 436, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Jones, K.A. CK2 controls the recruitment of Wnt regulators to target genes in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Yamashita, R.; Sugano, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakai, K. DBTSS: DataBase of Transcriptional Start Sites progress report in 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D150–D154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’leary, N.A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J.B.; Anderson, W.R.; Falk, R.; Hem, V.; Tsuchiya, M.T.N.; Schuler, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Torcivia, J.; et al. Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, C.; Montenarh, M. Protein kinase CK2 in development and differentiation. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 6, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, D.; Pandit, V.; Nohe, A. The Role of Protein Kinase CK2 in Development and Disease Progression: A Critical Review. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; D’aMore, C.; Cesaro, L.; Sarno, S.; Pinna, L.A.; Ruzzene, M.; Salvi, M. How can a traffic light properly work if it is always green? The paradox of CK2 signaling. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 56, 321–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.M.J.; Ortega, C.E.; Sheikh, A.; Lee, M.; Abdul-Rassoul, H.; Hartshorn, K.L.; Dominguez, I. CK2 in Cancer: Cellular and Biochemical Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Target. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Start Position | End Position | CAGE Tag Count | Normalized CAGE Tag Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSNK2A1 | 543,720 | 543,819 | 258,674 | 1 |

| CSNK2A1 | 543,620 | 543,719 | 6418 | 0.02481115 |

| CSNK2A1 | 483,372 | 483,471 | 5076 | 0.01962316 |

| CSNK2A1 | 483,678 | 483,777 | 4640 | 0.01793764 |

| CSNK2A1 | 483,270 | 483,369 | 1470 | 0.00568283 |

| CSNK2A2 | 58,163,248 | 58,163,347 | 19,973 | 1 |

| CSNK2A2 | 58,162,073 | 58,162,172 | 1619 | 0.08105943 |

| CSNK2A2 | 58,163,348 | 58,163,447 | 1257 | 0.06293496 |

| CSNK2A2 | 58,162,587 | 58,162,686 | 899 | 0.04501076 |

| CSNK2A2 | 58,163,731 | 58,163,830 | 812 | 0.04065488 |

| CSNK2A3 | 11,353,216 | 11,353,315 | 2616 | 1 |

| CSNK2A3 | 11,352,749 | 11,352,848 | 813 | 0.31077982 |

| CSNK2A3 | 11,352,613 | 11,352,712 | 503 | 0.19227829 |

| CSNK2A3 | 11,352,960 | 11,353,059 | 478 | 0.18272171 |

| CSNK2A3 | 11,352,443 | 11,352,542 | 445 | 0.17010703 |

| CSNK2B | 31,666,053 | 31,666,152 | 917,311 | 1 |

| CSNK2B | 31,668,531 | 31,668,630 | 9224 | 0.01005548 |

| CSNK2B | 31,666,784 | 31,666,883 | 7262 | 0.00791662 |

| CSNK2B | 31,669,324 | 31,669,423 | 5956 | 0.00649289 |

| CSNK2B | 31,667,852 | 31,667,951 | 5559 | 0.0060601 |

| Core Promoter Motif | Consensus Sequence | Position Relative to TSS | Bound By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inr | BBCABW | −3 to +3 | TAF1, TAF2 |

| Inr | YR | −1 to +1 | TAF1, TAF2 |

| Non-canonical Inr | YC | −1 to +1 | TBP-related factor 2 |

| 5′TOP | YC plus 4-15 Y’s | −1 to +5 to +16 | |

| TATA box | TATAWAWR | −31 to −24 | TBP |

| BREd | RTDKKKK | −23 to −17 | TFIIB |

| BREu | SSRCGCC | −38 to −32 | TFIIB |

| DCEI | CTTC | +6 to +11 | TAF1 |

| DCEII | CTGT | +16 to +21 | TAF1 |

| DCEIII | AGC | +30 to +34 | TAF1 |

| DPE | RGWCGTG | +28 to +34 | TAF6, TAF9, possibly TAF1 |

| DPE | RGWYVT | +28 to +33 | TAF6, TAF9, possibly TAF1 |

| DRE | WATCGATW | −100 to −1 | Dref |

| Pause button | KCGRWCG | +25 to +35 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilson, N.G.; Basra, J.S.; Dominguez, I. Bioinformatic Investigation of Regulatory Elements in the Core Promoters of CK2 Genes and Pseudogene. Kinases Phosphatases 2025, 3, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040022

Wilson NG, Basra JS, Dominguez I. Bioinformatic Investigation of Regulatory Elements in the Core Promoters of CK2 Genes and Pseudogene. Kinases and Phosphatases. 2025; 3(4):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040022

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilson, Nicholas G., Jesse S. Basra, and Isabel Dominguez. 2025. "Bioinformatic Investigation of Regulatory Elements in the Core Promoters of CK2 Genes and Pseudogene" Kinases and Phosphatases 3, no. 4: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040022

APA StyleWilson, N. G., Basra, J. S., & Dominguez, I. (2025). Bioinformatic Investigation of Regulatory Elements in the Core Promoters of CK2 Genes and Pseudogene. Kinases and Phosphatases, 3(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040022