Definition

Sport in Spain during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939–1975) underwent significant evolution across three distinct political phases: autarky, the technocratic stage, and late Francoism. Each of these periods was characterized by different approaches and uses of sport within the regime’s political structure. In the early years, sport was primarily employed as a tool for propaganda and social control, aligning with the authoritarian values of the state. Subsequently, with the rise of technocrats in the 1960s, reforms were implemented to promote the structural development of the sports system, fostering its modernization and the creation of specialized institutions. Finally, in the late Francoist period, sport became an instrument for international projection, as Spain increased its participation in international competitions and hosted sporting events. This entry analyzes the primary governmental initiatives for the organization and promotion of sport during the Franco regime, with particular attention to the administrative roles played by figures such as José Antonio Elola-Olaso and Juan Antonio Samaranch in the evolving structure of the Spanish sports system. Through an analysis based on documentary sources, it provides a comprehensive overview of Francoist sports policies, their objectives, and their impact on Spanish society. In this regard, sport under Franco’s rule was not only a means of political control but also laid the foundation for the later professionalization and globalization of Spanish sport.

1. History

The dictatorship of General Francisco Franco Bahamonde (1892–1975) marked a totalitarian era in contemporary Spanish history, lasting from the end of the Civil War (1 April 1939) until Franco’s death (20 November 1975). During this period, the regime employed a range of political, social, and economic strategies to consolidate its control, adjusting to both domestic and international developments. Most historians divide this extended period into three phases: autarky, developmental Francoism—also referred to as the technocratic stage—and late Francoism [1,2].

In its initial phase, the regime relied on domestic repression and pursued an autarkic economic model. This strategy faced further challenges following the defeat of ideologically aligned totalitarian states—Germany, Italy, and Japan—during World War II, which led to the geopolitical ascendancy of the Western Allies, initially in cooperation with the USSR for strategic purposes [3].

The autarkic model aimed, though unrealistically, to achieve national self-sufficiency by replacing imports with domestic production. Its implementation failed, resulting in significant social imbalances and an inability to meet basic societal needs [4]. These problems were especially acute during the so-called Blue Period (1939–1945).

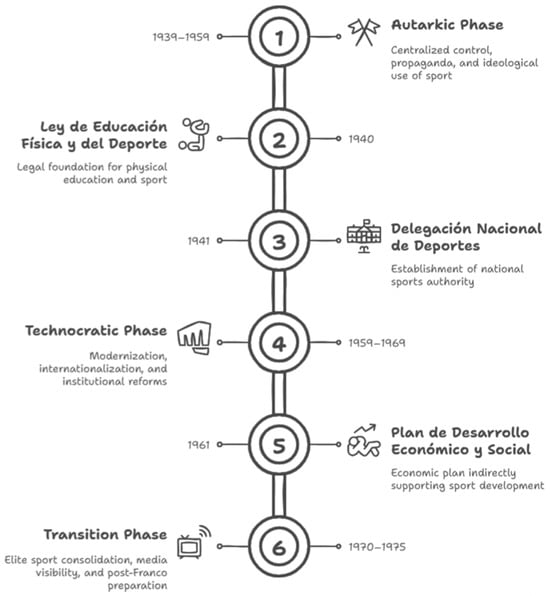

By the late 1950s, political isolation and flawed economic policies had pushed Spanish society toward collapse. Indicators of the crisis included rising living costs, growing public debt, shrinking reserves, a widening trade deficit, inflation reaching 42 pesetas per U.S. dollar, and unsustainable public spending. This critical situation demanded substantial reform to avoid systemic failure. It created an opening for the School of Public Administration in Alcalá de Henares and reformist figures within the regime—particularly Laureano López Rodó and Luis Carrero Blanco—to advocate for internal change. Nonetheless, this period was marked by tensions between hardline and reformist factions within Francoism. The regime remained ambivalent: while the repression of political dissent persisted, efforts were also made to improve the population’s material and economic conditions. Figure 1 illustrates the key phases in the evolution of Francoist sport.

Figure 1.

Sport Francoism: key milestones and phases.

2. From an Ideological Tool to Structural Legacy: The Role of Sport Under Francoism

This section is organized thematically to address the main structural dimensions through which sport was developed and instrumentalized under Francoism. The distinctive sub-headings reflect the dual nature of sport policy during the dictatorship—shaped both by institutional developments and by the influence of key individuals, such as Elola-Olaso and Samaranch.

2.1. Early Francoism: Sport Under Autarky

Sport was not separate from the broader sociopolitical context described above. Blanco Rivero [5] identified the period between 1939 and 1950—commonly referred to as early Francoism—as marked by limited resources and poor infrastructure in the aftermath of the Civil War. In subsequent years, the state of national sport improved, though it remained closely aligned with the political and ideological aims of the regime [6]. According to Viuda-Serrano [7], Francoist sports policy was based on three core principles: (1) sport was a matter of state, entirely controlled by authorities who regulated its organization at all levels; (2) it functioned as a tool for mass control, alongside other media used to shape public opinion; and (3) it served as a showcase to the international community, projecting an image of normalcy [8].

All sports activity—whether federated, military, or affiliated with the Falangist Movement—was overseen, directly or indirectly, by the National Sports Delegation (Delegación Nacional de Deportes, DND), established by decree in 1941. Its Organic Statute was first published in the Boletín del Movimiento of the Traditionalist Spanish Falange and the J.O.N.S., and later reproduced in the Official Gazette of the National Sports Delegation of the F.E.T. and the J.O.N.S. on 28 August 1945 [9,10]. Four years after its creation, Article 40 of the Organic Statute (Order of 7 June 1945) formally established that the National Sports Federations, under the supervision of the DND, served as the technical and administrative bodies responsible for promoting their respective disciplines on behalf of their corresponding international federations. These federations thus became parastatal entities, hierarchically subordinate to the state through the DND [11,12].

From 5 March 1951 to 12 April 1956, Franco entrusted the leadership of Spanish sport to General José Moscardó Ituarte (1878–1956), Count of the Alcázar of Toledo, renowned for his role in the defense of the fortress and his military background. In addition to his appointment as the first National Delegate for Sports, Moscardó was named President of the Spanish Olympic Committee (COE), thereby concentrating two roles that contradicted the principles of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Although the COE had been established in 1902 as a politically independent entity, after the Civil War Franco mandated that all sports institutions be placed under Falangist control (Article 2 of the Decree of 22 February 1941), making the COE subordinate to the DND.

The Physical Education Act of 1961 introduced partial reforms to this arrangement. It stipulated that the COE would be governed solely by its Statute, as approved by the IOC (Articles 20f, 25, and 26), thereby granting it formal—though largely theoretical—independence from other state institutions. Full legal autonomy was not achieved until after Franco’s death, with the enactment of the Law of Physical Culture and Sport in 1980, followed by the Sports Law of 15 October 1990.

A comparable institutional path was undertaken by the National Sports Delegation (DND) during the final years of the Franco regime. Royal Decree 2690/1978, enacted on 3 November under the direction of National Delegate Benito Castejón Paz, laid the groundwork for the legal formation of the Higher Sports Council (Consejo Superior de Deportes, CSD). Despite certain limitations, this decree marked a significant turning point in the legal configuration of Spanish sport [13]. During this period, the highest positions of responsibility in sport—including the DND, the Spanish Olympic Committee (COE), and, in many cases, the national federations—were controlled by the government through the DND [14] and assigned to war heroes, military officers, Falangists, and regime-affiliated politicians [15]. As a result, public sports activity operated under the centralized control of the DND, organized within a strictly hierarchical structure overseen by the regime [16]. According to Bielsa and Vizuete [17], this was a period in which the values of sport and physical activity became closely aligned with the authoritarian principles of Francoism, turning physical education into a political tool used to legitimize state policies and expand the regime’s social base.

Public interest in sport remained limited, especially regarding physical activity. Attention was largely confined to a few high-profile clubs and athletes: Real Madrid in football and basketball; boxers such as Luis Folledo and Fred Galiana; cyclists including Federico Martín Bahamontes—winner of the 1959 Tour de France from Toledo—Guillermo Timoner, Jesús Loroño, Bernardo Ruiz, Fernando Manzaneque, and Miguel Poblet; tennis players Manuel Santana and Andrés Gimeno; motorcyclist Ángel Nieto; and gymnast Joaquín Blume, among few others [7,18]. The general disinterest in physical activity and its relevance for public health is partly explained by the fact that Physical Education was not introduced into schools until 1950 [19].

Spanish sport at the time mirrored the isolationist stance of national politics, a position that intensified when competition involved countries from the communist bloc. Notable examples include Franco’s boycott of the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games in protest against the Soviet intervention in Budapest and the prohibition of the Spanish national football team from competing against the USSR in the inaugural European Nations Championship in 1960 [20,21].

2.2. The Technocratic Turn: Sport and Government Reform

In 1950, the UN General Assembly authorized, through Resolution 386 of 4 November (38 votes in favor, 10 against, 12 abstentions), the return of ambassadors and plenipotentiary ministers to Madrid. This decision marked the beginning of a phase of consolidation for the Franco regime, which took further shape in 1953 with two key diplomatic milestones: the signing of the Concordat with the Holy See on 27 August, and the Madrid Pacts with the United States on 23 September. The latter permitted the establishment of U.S. military bases in Spanish territory, including the Morón Air Base, Torrejón de Ardoz Air Base, Zaragoza Air Base, and Rota Naval Base. This process culminated in Spain’s official admission to the United Nations on 14 December 1955 [22]. This international repositioning, combined with broader geopolitical changes following World War II and the onset of the Cold War, marked the end of autarky and the beginning of a period of relative openness. Between 1957 and 1969, so-called Technocrats assumed key positions within the Spanish government, initiating a phase of economic expansion often referred to as the “golden sixties.” The technocratic model was defined by its reliance on socio-economic planning grounded in scientific analysis, economic rationalism, and the widespread application of technology to promote collective well-being [23].

To implement this model, a group of Opus Dei-affiliated technocrats entered the regime’s Eighth Government. Among them were Alberto Ullastres Calvo (1914–2001), Minister of Commerce; Mariano Navarro Rubio (1913–2001), Minister of Finance; and Raimundo López Rodó (1920–2000), Head of the General Technical Secretariat of the Undersecretariat of the Presidency. Their ascent was supported by Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco (1904–1973), who was later assassinated by the terrorist group ETA on 20 December 1973, during Operation Ogre. These reformist policymakers commissioned economist Joan Sardà i Dexeus (1910–1995), along with other experts from the Ministry of Commerce and the Bank of Spain—including Enrique Fuentes Quintana (1924–2007), Manuel Varela Parache (1926–2011), Carlos Bustelo y García del Real (b. 1936), and Luis Ángel Rojo Duque (1934–2011)—to design urgently needed reforms.

The Economic Stabilization and Liberalization Plan, enacted by Decree-Law on Economic Planning on 21 July 1959, marked the onset of the so-called “Spanish economic miracle”. Its results included a balance of payment surplus, reduced inflation, increased foreign investment, and growth in gold and currency reserves [24]. The plan also liberalized the economy and accelerated the decline of rural life through urban development. Foreign capital began to play a significant role in the Spanish economy. The plan rested on three main objectives: (a) fiscal discipline to support trade liberalization; (b) limited domestic economic liberalization; and (c) external liberalization through the rationalization and unification of the exchange rate, which included a nearly 50% devaluation of the peseta (from 42 to 60 pesetas per U.S. dollar).

With the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), of which Spain had been a member since July 1958, and assistance from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), along with over $1.5 billion in U.S. aid—including direct funding, contributions under Public Law 480, and allocations from the McCarran Amendment—the economic strategy crafted by the regime’s technocrats proved highly effective [25].

In 1962, the presence of technocrats in the government increased through the appointments of Gregorio López-Bravo de Castro (1923–1985) as Minister of Industry and Manuel Lora-Tamayo Martín (1904–2002) as Minister of Education and Science. In 1965, Laureano López Rodó joined the cabinet in a newly created Ministry of Development Planning. While the economic reforms were substantial and indisputable, social and political change remained limited, despite increasing domestic opposition from labor groups, student movements, and the emergence of terrorist organizations such as ETA. Franco and the core of the regime resisted such reforms. The only notable concessions made by the so-called “openers” within the regime were the approval of the Press and Printing Law in March 1966—promoted by Manuel Fraga Iribarne (1922–2012), Minister of Information and Tourism—and the Law of Religious Freedom in June 1967, under Foreign Minister Fernando María Castiella y Maiz (1907–1976), in line with the new directions of the Second Vatican Council.

Simultaneously, the Organic Law of the State and other fundamental laws contributed to the institutionalization of Francoism. Approved by referendum on December 14, 1966—with a reported 98.01% of voters in favor—this legal framework consolidated the regime’s internal architecture. In the short term, these legislative and political reforms led to significant outcomes: sustained economic growth (7.31% annually between 1961 and 1973); a sharp decline in unemployment; rapid industrialization (Spain became the 12th largest industrial power by 1970); extensive agrarian reform; a surge in urbanization (66% urban population); the emergence of a new working class; and growth in the service sector, fueled largely by the country’s first tourism boom. Per capita income rose from $1042 in 1960 to $1904 in 1970. The middle class expanded (55% of the population), literacy rates improved (95% among men, 88% among women), and compulsory education was reinforced. Women’s participation in the labor market increased to 28%. At the same time, infant mortality declined, birth rates remained high (the “Baby Boom”), and life expectancy rose to 73 years by 1975. These transformations signaled the rise of a consumer society, marked by the proliferation of televisions, household appliances, automobiles, and a growing culture of leisure—holidays, tourism, and increased participation in sport [26].

The regime’s strategy toward international sporting engagement began to shift following the appointment of José Antonio Elola-Olaso e Idiacaiz (1909–1976), former National Delegate of the Youth Front, to the leadership of the National Sports Delegation (DND). This period is often regarded as a phase of de-Falangization, a process already underway in other areas of Spanish political life [17]. During this time, sport was increasingly used as a means of projecting a modern image of Spain to the international community [27].

The victories of Real Madrid CF in the first five editions of the European Cup (1955–1960) coincided with the signing of the Treaty of Rome and the establishment of the European Economic Community in 1957. These developments further encouraged the regime’s efforts to end Spain’s international isolation and to improve relations with European powers. Although the government initially prohibited national teams from competing against those of the USSR and other socialist countries—while adopting a more lenient stance in other disciplines such as basketball—sporting relations were eventually normalized. Spain also succeeded in organizing international sporting events, which were strategically employed as instruments of propaganda [28,29]. Sport—particularly football, due to its wide appeal—thus became a political priority for the dictatorship.

2.3. Elola-Olaso and Institutional Modernization

In 1956, following the death of Moscardó and during the tenure of Basque architect José Luis Arrese y Magra (1905–1986) as Minister Secretary General of the Movement, José Antonio Elola-Olaso Idiacaiz was appointed National Delegate (8 May 1956–23 December 1966). Born in 1909 in Argentina to a family of Spanish emigrants, Elola-Olaso was a committed Falangist who fought on the rebel side during the Civil War. Trained in law at the University of Valladolid, he held several positions under the regime, including membership in the National Council of the Traditionalist Spanish Falange and the J.O.N.S. Notably, he became the first National Delegate of the Youth Front in 1941, a role from which Elola-Olaso transitioned into a leadership role in Spanish sport, aligning institutional reforms with the regime’s evolving political and international goals.

Under his leadership, the highest governing body of Spanish sport was renamed the National Delegation of Physical Education and Sports, by decree on 12 June 1956. It was attached to the General Secretariat of the Movement—an initiative that, although modest and incipient, represented an early attempt to modernize and reform the country’s sporting structures. During his tenure, the DND shifted its strategic focus, launching various campaigns to promote physical education and sport. One of the key changes was the replacement of the military-based training model—previously led by the Central Army Gymnastics School in Toledo—with a civilian framework supervised by Falangist organizations.

2.4. The Physical Education Act

One of the most significant developments during this period was the enactment of the Physical Education Law in 1961, also known as the Elola-Olaso Law, which remained in force until the adoption of the Sports Law in 1980 [30]. As a result, Physical Education and Sport were formally recognized by the State as matters of public interest and as rights of all Spanish citizens. The law reflected a substantial transformation in sport policy, framing Physical Education as an essential component of holistic individual education.

The law led, both directly and indirectly, to a series of structural advances that laid the foundation for future developments in sport. Among the most notable was the creation of the Joaquín Blume Residences, Spain’s first centers for athletic technification, intended to accommodate elite national athletes. Named in honor of Catalan gymnast Joaquín Blume Carreras (1933–1959), European champion in Paris (1957), who died two years later in a plane crash in the Serranía de Cuenca alongside members of the national team, the residences symbolized a new phase of institutional support. Two centers were established: the Blume Residence in Madrid, initially located in the former Moscardó Gymnasium (built in 1940 on Pilar Street in Zaragoza), and the Blume Residence in Barcelona, inaugurated by Elola-Olaso in October 1960 in Esplugues de Llobregat and operational the following year. In 1964, a 25 m swimming pool and a medical center were added to the latter facility.

Another milestone in this context was the establishment of the National Institute of Physical Education (INEF) in Madrid, in accordance with Law 77/61 on Physical Education. The first academic year officially began on 3 November 1967, with José María Cagigal Gutiérrez (1928–1983) as its first director (1967–1977). Prior to the foundation of this institution—considered advanced for its time—the training of professionals in Physical Education and Sport was carried out in several institutions, including the following: the Central School of Toledo, created under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship in 1919; the José Antonio National Academy of Commands, inaugurated by decree on 2 September 1941, with Alberto Aníbal Álvarez as its first director; the Isabel la Católica National Academy (Decree of 2 September 1941); and the Miguel Blasco Vilatela Teacher Training School, established in 1956.

2.5. Scientific Dissemination in Francoist Sport

During Elola-Olaso’s tenure, several scientific journals and technical-informative publications in the field of Physical Activity and Sport were launched, serving as important platforms for promoting research and knowledge dissemination. The first of these was the Spanish Journal of Physical Education and Sports, founded in Toledo in September 1949 and still active today. Its first director was Infantry Lieutenant Eleuterio Torrelo Rodríguez, delegate of the College of Physical Education Teachers in Toledo and instructor of wrestling initiation at the Central School of Physical Education in Toledo [31].

Citius–Altius–Fortius became the most prominent publication of this period. It was a specialized journal created in 1956 under the sponsorship of the Spanish Olympic Committee and remained in circulation until 1974. José María Cagigal Gutiérrez, a key academic contributor to the project and the founding director of INEF Madrid, served as deputy director and regular contributor. However, the journal’s greatest international visibility came under the direction of Miguel Piernavieja del Pozo (1916–1983), a multilingual lawyer and historian from the Canary Islands, known for his participation in the Lake Ilmen campaign. Under his leadership, the journal became the leading Spanish scientific publication on sport during the 1960s and 1970s, and one of the most respected internationally [32]. Of the 28 contributors featured in its first issue, 15 were prominent international authors—including Carl Diem, Walter Umminger, Hermann Altrock, Ulrich Popplow, Erwin Mehl, Ferenc Mező, and Bruno Zauli—while 13 were Spanish, among them psychiatrist Juan José López Ibor, journalist Rafael Hernández Coronado, and physician Luis Agosti Romero.

Also noteworthy was the publication Sport 2000, active from 1968 to 1977, which covered topics in sports science alongside opinion pieces, interviews, technical reports, and event coverage. Its editorial rigor distinguished it from most sports journalism of the time.

2.6. Media Strategies and Sport Promotion

The expansion of sport during the Elola-Olaso period was also reflected in the growing attention it received from the media. In the early years of Francoism, as in other totalitarian regimes, the media played a central role in state propaganda. This function continued from the end of the Civil War throughout the dictatorship, serving both to maintain domestic control and to enhance the regime’s image abroad. The media’s repressive and manipulative origins can be traced to the Law for the Repression of Freemasonry and Communism (BOE, 2 March 1940) and the Law for State Security (BOE, 11 April 1941), under which the press, radio, and later television were integrated into the state’s ideological apparatus until the promulgation of the Press and Printing Law in 1966.

Before analyzing the press–sport relationship, it is essential to recognize that, in general, the press under Francoism was limited in number and lacked pluralism. Much of it belonged to the Prensa del Movimiento, the regime’s propaganda arm, supported by the confiscation of assets—including property, furnishings, and documents—of the Popular Front, carried out under the Decree of 13 September 1936, on political parties [33]. These assets, following the Order of 10 August 1938—which placed the press under the National Press Service of the Ministry of the Interior—and the development of the Press Law of 13 July 1940, became part of the patrimony of the National Delegation of Press and Propaganda of the Traditionalist Spanish Falange and the J.O.N.S. [34].

In this media landscape, Marca became the dominant sports newspaper. It originated in San Sebastián in 1938, moved to Madrid in 1940, and began publication in 1942 [35], reaching a circulation of 140,000 copies that same year [36]. In Catalonia, El Mundo Deportivo, established in 1906, played a significant role. Initially a weekly, it became a daily in 1929 and continued to shape regional sports journalism during the dictatorship.

Radio, despite the technical limitations of the time, quickly emerged as a key medium for both entertainment and information in early Francoist Spain. It provided escapism through musical programs, children’s shows, contests, comedy, and dramas, while also serving as a platform for religious propaganda—such as the broadcasts of Father Venancio Marcos—and for political messaging, including the Spoken Newspapers on Radio Nacional de España (RNE), which also covered sport [37]. The first sports broadcast in Spain was a match between Real Madrid and Real Zaragoza, aired by Unión Radio in the spring of 1927. During the dictatorship, Marcador, directed by Carlos Alcaraz, became a prominent program on RNE, a station created in Salamanca on 19 January 1937, by Galician general José Millán-Astray y Terreros (1879–1954). Dependent on the Undersecretariat of Press and Propaganda of the Ministry of the Interior, its first director was the Bilbao journalist Jacinto Miquelena. In 1953, Marcador was replaced by Radiogaceta de los Deportes, which responded to the growing public demand for sports coverage. Around the same time, Carrusel Deportivo debuted on Cadena SER, directed by Vicente Marco (1916–2008) and hosted by Chilean-born journalist Bobby Deglané Portocarrero (1905–1983). These programs, centered primarily on football, remained the most effective form of sports broadcasting until the arrival of television. In 1964, following administrative reforms, RNE underwent major technological and organizational improvements, enabling full national and partial European coverage.

Television became the third major pillar in the promotion of sport during the dictatorship [20]. It served to popularize mass-participation sports [38] and, conversely, benefited from the popularity of football, which played a key role in the development of Spanish television [39]. Televisión Española (TVE), a division of RTVE, has been the national public broadcaster since 1956, operating under a state monopoly and central government control [40]. Regular broadcasting began on October 28 of that year, though reception was initially limited to the Madrid area due to the scarcity of television sets and restricted signal range [39]. The first live sports broadcast took place three years later: a football match between Real Madrid and FC Barcelona at the Chamartín Stadium on 15 February 1959. Prior to this, only recorded content had been aired, such as matches between Atlético de Madrid and Real Madrid (1958) and Spain vs. France (1958). According to Bonaut and Ojer [41], this 1959 broadcast had both social and economic impacts in areas where the signal was received, particularly in Barcelona. As a preliminary test, the Real Madrid–Racing de Santander match was transmitted on 24 April 1954 [42].

A year later, football justified TVE’s first participation in the Eurovision network, with the live broadcast of the European Cup final between Real Madrid and Eintracht Frankfurt on 18 May. Another key moment was the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, which were broadcast internationally via satellite. As Bonaut and Ojer [41] note, sports programs of the period—beyond match broadcasts—formed part of broader national pedagogical and popular education initiatives. These included titles such as Learn a Sport, Sports, Sport, New Humanism, Champions, The Olympic Adventure, Stories of Football, First Division, Yesterday, Sunday, and School of Champions.

The 1966 Press and Printing Law, approved by the Cortes on 15 March and promoted by Galician jurist Manuel Fraga Iribarne—Doctor of Law and graduate in Political and Economic Sciences—represented a turning point for Spanish media. Fraga, a leading figure of the regime from 1962 and later founder of Alianza Popular, finalized the law initially developed under Gabriel Arias Salgado. It was passed despite opposition from Carrero Blanco and Franco’s indifference. While ostensibly regulating freedom of expression to preserve regime interests, some historians argue that it contributed to a shift in Spain’s cultural climate [43,44].

Within this evolving media context, sports journalists operated with comparatively greater independence than their counterparts in other sectors, although still under surveillance and occasional censorship. Their autonomy gradually expanded, at least in appearance, throughout the final years of the regime [14,45].

2.7. National Competitions and Youth Engagement

The structural development of sport in Francoist Spain was also reflected by the organization, promotion, and implementation of various championships. These events can be divided into two main categories. On one hand, there were national competitions aimed at encouraging youth participation in sport, such as the National School Games, National Federative Championships, Women’s Section Games, the Games of the International Sports Federation of Catholic Education, and the Spanish University Championships—all of which fostered widespread competitive engagement. On the other hand, the absolute-category championships or leagues were organized by the national sports federations.

The National School Games (Juegos Escolares Nacionales, JEN) were launched in the 1948/1949 academic year by José Antonio Elola-Olaso, then National Delegate of the Youth Front, and General Joaquín Agulla Jiménez-Coronado (1903–1971), National Secretary of Physical Education and Sports. They reached their peak during the 1960s under the leadership of Matías Rubio and José Luis Lasaosa [46]. Renamed the Youth Games in 1967/1968, the competitions were held exclusively for boys and divided into three or four stages (Local, Provincial, Sector, and National), taking place over the academic year. The national finals were typically held in Madrid, at the facilities of the Ciudad Universitaria or Vallehermoso, with some exceptions: Santander (1970, children’s category), Barcelona (1971, youth category), and Málaga (1972 and 1973, children’s category). Participation grew substantially, from 30,902 students in 1958 to 272,713 in 1970 [47]. Initially, events were held in two categories—children and youth—though only the latter had a final phase. By 1958/1959, three distinct categories had been established: Infantil “A” (ages 11–13), Infantil “B” (ages 14–15), and Juvenil (ages 16–18). In 1963/1964, the Infantil “A” category was renamed Alevín, and the Cadete category was introduced in 1973/1974.

Women’s participation was structured primarily through the Games of the Women’s Section. The Women’s Section, the female branch of the Falange, was founded during the Second Republic on 13 May 1933, under the leadership of Pilar Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia (1907–1991), sister of Falange founder José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia (1903–1936). It remained active until 1977, along with other entities under the General Secretariat of the Movement, until the reorganization implemented by Royal Decree-Law of 1 April 1977 (BOE, 7 April 1977) [48]. Among its responsibilities—though marginal—were the training of female Physical Education teachers and the organization of activities for women. However, these were subject to significant restrictions under the Law of 6 December 1940, which opposed individual and competitive sports for women on the grounds that such activities compromised traditional femininity [9]. The sports exhibitions promoted by the Women’s Section aimed to reinforce gender roles aligned with Francoist ideology: the image of a healthy, active woman prepared for her duties as wife and mother [49]. Nevertheless, several prominent female athletes mobilized to promote greater inclusion of women in sport [50].

Another key initiative to promote youth participation in sport was the Spanish University Championships (Campeonatos de España Universitarios, CEU). During the dictatorship, university-level sport was managed by the Spanish University Union (Sindicato Español Universitario, SEU), established on 21 November 1933 and institutionalized in 1940 as part of the Youth Front and, by extension, subordinated to the DND in subsequent years. In 1942, General Order No. 115 of the SEU National Headquarters authorized the organization of the National University Games. Thirteen university districts took part in the first edition, though these competitions lacked continuity: only 18 editions were held between 1942 and 1970. The organization of student sport was not always smooth. Law 191/1964, of 24 December, concerning associations, generated tension between the State and students by eliminating student representation in the management of national sports activities. That same year, the Order of 28 September 1964 introduced a Physical Education Plan for universities, technical colleges, and professional schools. University sport gradually evolved, culminating in the foundation of the Spanish Federation of University Sports (Federación Española de Deportes Universitarios, FEDU) by Order of 25 April 1970, under the authority of the National Delegation of Physical Education and Sports.

Internationally, Spanish university sport was affiliated with the International Conuffissariat of University Sport (ICUS), which later became the International University Sports Federation (FISU). In 1959, the first World University Games were held in Turin, Italy. From that point forward, they became known as the Universiades [51].

2.8. Sport Diplomacy and International Projection

All political regimes—whether totalitarian or otherwise—tend to use the organization of major international sporting events as instruments of propaganda and international projection. In the early years of Franco’s dictatorship, however, Spain hosted only a small number of international events, most of which had limited scale and visibility compared to those organized in other European countries during the same period. One notable exception was the II Mediterranean Games, held in Barcelona from 16 to 25 July 1955. The competition took place in various local venues, including the Montjuïc Stadium, originally inaugurated in 1929 by King Alfonso XIII during the International Exhibition and later renovated for the occasion.

Although major international sporting events offered an ideal opportunity for the regime to project an image of openness and modernity, the number of such events held in Spain remained limited and had relatively modest international relevance. Notable examples include the VI European Judo Championship, held in Barcelona on 10 and 11 May 1958, where Spain secured four bronze medals (Enrique Aparicio, Eizaguirre Gómez, José Pons, and Alan Petherbridge); the XIV Men’s Roller Hockey World Championship, held in Madrid from 7 to 15 May 1960, in which Spain finished in second place; and the Basque Pelota World Championship, played in Pamplona from 20 to 30 September 1962, where Spanish athletes earned three gold and five silver medals. In May 1964, Spain hosted the XVI Men’s Roller Hockey World Championship in Barcelona, achieving overall victory. Finally, the XIII European Judo Championship took place in Madrid on 23 and 24 May 1965, with Spain winning a single bronze medal, awarded to Salvador Álvarez in the −70 kg professional category.

A particularly notable initiative was the Madrid Olympic bid for the 1972 Games. On 26 December 1965, the official candidacy was submitted. Previously, both Barcelona and Madrid had presented proposals to the Spanish Olympic Committee to host the event. In April 1966, during the IOC assembly in Rome, the Spanish delegation—led by Catalan diplomat Ramón Sedó Gómez (1912–1991)—sought international support despite significant economic constraints and reluctance from the regime’s economic ministries. The bid received strong backing from José Solís Ruiz (1913–1990), Secretary General of the Movement; Fernando María Castiella y Maiz (1907–1976), Minister of Foreign Affairs; and Manuel Fraga Iribarne (1922–2012), Minister of Information and Tourism. Ultimately, in the second round of voting, Madrid placed second with 15 votes, behind Munich (31 votes) and ahead of Montreal (1 vote) [52].

During the Elola-Olaso period, a range of additional measures and political initiatives contributed to the modernization of Spain’s previously outdated and inefficient sports system, characteristic of the early Francoist period. Among these was the creation of the Mutua General Deportiva (General Sports Mutual Society) in 1961, designed to provide healthcare services to athletes—with the exception of professional footballers, who had a separate system. From that point onward, undergoing a medical examination became a mandatory requirement for obtaining a sports license. The Mutual Society remained active until 2012.

In terms of the infrastructure, the Sports Facilities Plan played a pivotal role in expanding access to suitable venues for sport throughout the country. It was during the 1960s that most of the approximately 12,000 sports facilities built since 1940 were constructed [46]. However, it is important to note that the majority of these installations were financed with private capital, often supplemented by state support.

Several significant facilities were developed under the framework of this plan. The Palacio de los Deportes de Barcelona (Palau dels Esports), a covered multipurpose arena located at the base of Montjuïc, was designed by architect Josep Soteras i Mauri (1907–1989) and inaugurated in 1955 during the Mediterranean Games. In Madrid, the Palacio de los Deportes became a landmark of Francoist sports architecture. Conceived in 1953 by Elola-Olaso and inaugurated in 1956 on Plaza de Goya—formerly the site of the city’s bullring—it was designed by Catalan architects José Soteras i Mauri and Lorenzo García-Barbón Fernández de Henestrosa (1915–1999). The original structure was destroyed by fire in 2001 and rebuilt in 2005.

Another major project was the Ciudad Deportiva del Real Madrid (Real Madrid Sports City), constructed in 1963 under the presidency of Santiago Bernabéu de Yeste (1895–1978). In 1966, its facilities were expanded to include training grounds for the first team and youth divisions, swimming pools, and recreational areas, such as tennis courts, athletics tracks, and an ice rink. That same year, the complex was further enhanced by the addition of the Real Madrid Sports City Pavilion (later known as the Raimundo Saporta Pavilion), which served as the home court for the club’s basketball team for 38 years.

Finally, the Parque Sindical Puerta de Hierro (Puerta de Hierro Sports Union Park), designed by Madrid architect Manuel Muñoz Monasterio (1903–1969), opened its doors on 18 July 1955, as a large-scale recreational space for the city’s working-class population. Years later, it was proposed as the central hub of the Madrid 1972 Olympic bid.

2.9. Samaranch and the Transition to Mass Participation

On 26 December 1966, the Catalan businessman and politician José Antonio Samaranch Torelló (1920–2010), a former athlete and president of the Spanish Skating Federation, assumed leadership of both the National Sports Delegation (DND) and the Spanish Olympic Committee (COE), a role he held until 9 September 1970. During his tenure, efforts were made to expand public participation in sport, in alignment with the regime’s broader goals of social mobilization and international visibility. His contributions to sport during the dictatorship were closely supported by key collaborators, notably Benito Castejón Paz-Pardo (1928–2019), who held the DND post after him, and José María Cagigal Gutiérrez, the driving force behind the establishment of the National Institute of Physical Education (INEF).

Castejón, a career military officer and law graduate from the Aviation Legal Corps, served as National Delegate for Physical Education and Sports from September 1976 to April 1977. Later, he was appointed Secretary of State for Sport on 25 January 1980 and President of the Spanish Olympic Committee until 12 May 1980. He played an administrative role in early efforts to organize high-performance sport in Spain through institutional planning and state coordination, promoting the development of specialized training infrastructures—such as Technical and Sports Initiation Centers, Development Centers, and High-Performance Centers—with the aim of creating a competitive Spanish sporting elite. His proposals were formalized in Rationalizing Sports Policies [53], a study co-authored with Juan de Dios García-Martínez and José Rodríguez Carballada, presented to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. The work sought to define essential concepts for public sports policy and proposed a mathematical model for optimizing decision-making in this domain. A notable feature of the study was its rigorous use of statistical tools to support the model [53].

Another prominent figure in this period was José María Cagigal Gutiérrez (1928–1983). Born in Deusto (Biscay) into a large family, he initially entered the Society of Jesus in 1946, though he left before ordination during his theological studies in Frankfurt. During this time, he authored Hombres y Deporte [54], a text that marked a turning point in his academic and professional trajectory. He joined the DND during Elola-Olaso’s leadership as an advisor on the Physical Education Law and was appointed National Subdelegate for Physical Education and Sports in 1963. In 1966, he oversaw the creation of INEF Madrid. Like Castejón, his influence extended internationally, holding positions in major global organizations such as the International Council of Physical Education and Sport of UNESCO, the International Society of Sport Psychology, the International Federation of Physical Education, the International Olympic Academy, and the International Association of Higher Schools of Physical Education.

One of the key developments of this era was the implementation of national sports promotion campaigns. In 1966, the Council of Europe adopted the principle of “Sport for All” as a policy priority. Following successful programs in Germany, Belgium, and Norway, Spain launched Cuenta Contigo (1967–1979), its first major nationwide campaign to promote physical activity among the general public [55]. The campaign aimed to raise awareness of the benefits of an active lifestyle and to disseminate sports practices across the country, while simultaneously building a base of future athletes [13]. The campaign was directly overseen by Benito Castejón, then Secretary General of the DND. Its successor, Stay in Shape, We Count on You!, launched by Samaranch, focused on expanding basic sports infrastructure in small towns and cities, thereby promoting social and educational sport throughout the territory [17]. These initiatives laid the foundation for later campaigns that had significant social impact, such as In Shape and Pedaling (1978–1979–1982), Walking and Running (1978–1979–1982–1983), School Sport for All (1980), and Free Time Sport (1981).

The state-controlled newsreel NO-DO also played an important role in promoting grassroots sport. This weekly, 30 min audiovisual program was screened in all cinemas throughout Spain from 1943 to 1981. In 1968, NO-DO premiered the first edition of the Images of Sport project, with the attendance of Samaranch and Castejón. This edition included documentaries such as Sports in Spain, The Torch, and others dedicated to the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico [56]. The project continued until 1977, culminating in a documentary about long-distance runner Mariano Haro Cisneros, known as the “Lion of Becerril.” These short films aimed to promote physical activity among the general population [20]. The NO-DO initiative inspired similar programming on RTVE, such as Camino del Récord (1973), which encouraged youth sports participation from an educational perspective, and Torneo (1975–1979), which featured inter-school competitions in search of emerging talent [57].

3. Conclusions

As demonstrated throughout this study, the Franco dictatorship in Spain encompassed three distinct political phases that found parallel expression in the field of sport. The initial stage, marked by economic autarky and material scarcity, gave way to a second phase in which sport was primarily instrumentalized for propagandistic purposes. This ultimately led to a third stage, characterized by substantial investment in the development and promotion of sporting structures and practices. Within this latter period, the technocratic approach introduced by reformist actors had a profound influence on both the institutional fabric of sport and its mass diffusion.

The transformation of Spanish sport from the 1960s onward is closely associated with a set of key figures: José Antonio Elola-Olaso, José María Cagigal, Benito Castejón Paz, and Juan Antonio Samaranch. These individuals were central to the reorientation of sport away from its earlier militaristic and ideological framework, toward two major priorities: the technical development of elite sport and the widespread democratization of sports practice among the general population. Their efforts were reflected in the design and implementation of targeted policies and strategic plans, the promotion of scientific and journalistic dissemination, the organization of tournaments and competitions, and nationwide campaigns aimed at increasing public engagement in physical activity.

Although these policies were implemented within the framework of an authoritarian regime, they demonstrate how certain processes of institutional modernization could be developed in the field of sport through state structures oriented toward technical planning. This dynamic—where structural development coexists with mechanisms of ideological legitimation—may contribute to describing a set of processes as a starting point for future studies in comparable contexts. In the Spanish case, these developments enabled transformations that would eventually culminate in the organization of the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; methodology, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; investigation, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; resources, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; visualization, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; supervision, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R.; project administration, J.M.G.-M., A.S.-P. and J.A.G.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Olympic Studies Centers at UCAM and the University of A Coruña for their support in providing access to historical documents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DND | National Sports Delegation (Delegación Nacional de Deportes) |

| COE | Spanish Olympic Committee (Comité Olímpico Español) |

| INEF | National Institute of Physical Education (Instituto Nacional de Educación Física) |

| NO-DO | Noticiarios y Documentales (Newsreels and Documentaries) |

| JEN | National School Games (Juegos Escolares Nacionales) |

| SEU | Spanish University Union (Sindicato Español Universitario) |

| CEU | Spanish University Championships (Campeonatos de España Universitarios) |

| ICUS | International Conuffissariat of University Sport (antecesor de FISU) |

| FISU | International University Sports Federation (Federación Internacional de Deporte Universitario) |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos) |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund (Fondo Monetario Internacional) |

| UN | United Nations (Organización de las Naciones Unidas) |

| BOE | Official State Gazette (Boletín Oficial del Estado) |

| TVE | Televisión Española |

| RTVE | Spanish Radio and Television Corporation (Radio Televisión Española) |

| CSD | Higher Sports Council (Consejo Superior de Deportes) |

| FET y de las JONS | Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista |

| ICOC | International Olympic Committee (Comité Olímpico Internacional) |

| EEC | European Economic Community (Comunidad Económica Europea) |

References

- Tusell, J. History of Spain in the 20th Century. III, The Franco Dictatorship; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Juliá, S. Politics and Society. In La España del Siglo XX; Juliá, S., García, J.L., Jiménez, J.C., Fusi, J.P., Eds.; Marcial Pons Historia: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 15–321. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A. The Failure of Autarky: Spanish Economic Policy and the Post-World War Period (1945–1959). Espac. Tiempo Forma Ser. V Hist. Contemp. 1997, 10, 297–313. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Arco-Blanco, M.A. Dying of Hunger. Autarky, Scarcity, and Disease in Early Francoist Spain. Pasado Mem. Rev. Hist. Contemp. 2006, 5, 241–258. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Rivero, A. Sport and Society During Francoism: Its Organization and Development in Different Stages of the Dictatorship. 2008. Available online: http://museodeljuego.org/wp-content/uploads/contenidos_0000000289_docu1.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2023). (In Spanish).

- López Iglesias, V. Sport as a State Tool to Strengthen the Image of Francoism: Sport Policy during Early Francoism (1941–1948). Vis. Rev. 2024, 16, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Serrano, A. Spain in the Olympic Games of Early Francoism: The Important Thing Was to Participate. Mater. Hist. Deporte 2015, Suppl. S2, 257–262. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10433/2526 (accessed on 11 January 2024). (In Spanish).

- Simón, J.A. Football and International Relations Under Francoism, 1937–1975; Routledge: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Arribas, J.C. Youth, Sport, and Falangism. The Youth Front, The Women’s Section, and the Sports of the Movement. In Atletas y Ciudadanos. Historia Social del Deporte en España, 1870–2010; Pujadas, X., Ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 233–272. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Macías, G. The Camps of Franco’s Youth Phalanxes (1942–1959): Discipline, Obedience and Ardor in the Service of the Phalanx and Spain. Mater. Hist. Deporte 2024, 28, 100–116. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, L.M. Sport and the State; Editorial Labor: Barcelona, Spain, 1979. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- García Martí, C. Con el viento en contra: El atletismo español en el primer franquismo (1939–1956). Citius Altius Fortius 2024, 17, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, L.M.; Arnaldo, E.; González-Serrano, J.; Mayoral, F.; Ruíz-Navarro, J.L. Sports Law; Editorial Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 1992. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D. Football and Francoism; Editorial Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1987. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- González-Aja, T. Sports Policy in Spain during the Republic and Francoism. In Sport y Autoritarismos. La Utilización del Deporte por el Comunismo y el Fascismo; González-Aja, T., Ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2002; pp. 169–202. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Santacana, C. Mirror of a Regime: Transformation of Sports Structures and Their Political and Propaganda Use, 1939–1961. In Atletas y Ciudadanos. Historia Social del Deporte en España, 1870–2010; Pujadas, X., Ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 205–232. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bielsa, R.; Vizuete, M. The National Sports Delegation 1943–1975: Structure and Sports Organization; Editorial Académica Española: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2012. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Berastegui, J.C. Manolo Santana: The Smiling Quixotic Hero Who Turned Tennis into a Mass Sport in Spain. Mater. Hist. Deporte 2024, 28, 47–62. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I. Historical Evolution of Initial Training for Physical Education Teachers in Spain. Rev. Fuentes 2002, 4, 1–24. Available online: https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/fuentes/article/view/2435 (accessed on 19 January 2024). (In Spanish).

- Simón, J.A.; Castañeda, E.A. From Francoism to Democracy: The Transition of Sport in Spain through the Analysis of “Sports Images” Documentaries, 1968–1977. Stor. Sport Riv. Studi Contemp. 2019, 1, 23–40. Available online: https://storia-sport.it/index.php/sp/article/view/70 (accessed on 20 January 2024). (In Spanish).

- Simón, J.A.; Rieck, J. Football, Propaganda and International Relations under Francoism: The 1960 and 1964 European Nations Cup and Their Impact on the International Press. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2022, 39, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleonart, A.J. Spain’s Entry into the UN: Obstacles and Impulses. Cuad. Hist. Contemp. 1995, 17, 101–119. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CHCO/article/view/CHCO9595110101A (accessed on 22 January 2024). (In Spanish).

- Cañellas-Mas, A. Francoist Technocracy: The Ideological Meaning of Economic Development. Stud. Histórica Hist. Contemp. 2006, 24, 257–289. Available online: https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/0213-2087/article/view/1019 (accessed on 26 January 2024). (In Spanish).

- Flores, A.S. Evolution of the Spanish Balance of Payments during the Period 1961–1977: Analysis of the Basic Balance. An. Univ. Murcia (Derecho) 1975, 3–4, 531–550. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/analesumderecho/article/view/105301/100251 (accessed on 3 February 2024). (In Spanish).

- Cavalieri, E. Spain and the IMF: The Integration of the Spanish Economy into the International Monetary System, 1943–1959; Estudios de Historia Económica 65; Banco de España: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/EstudiosHistoriaEconomica/Fic/roja65.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024). (In Spanish)

- Sánchez-Biosca, V. The Cultures of Late Francoism. Ayer 2007, 68, 89–110. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41325309 (accessed on 26 February 2024). (In Spanish).

- Viuda-Serrano, A.; González-Aja, T. Paper Heroes: Sport and the Press as Political Propaganda Tools of Fascism and Francoism. A Comparative Historical Perspective. Hist. Comun. Soc. 2012, 17, 39–66. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, J.P. A Century of Spain. The Culture; Marcial Pons: Madrid, Spain, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, J.P. The Diplomacy of the Ball: Sport and International Relations during Francoism. História Cult. 2015, 4, 165–189. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calatayud, F. From Amorós Gymnastics to Mass Sport (1770–1993): A Historical Approach to Physical Education and Sport in Spain; Oficina de Publicaciones del Ajuntament de València: Valencia, Spain, 2002. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga, A. Spanish Journal of Physical Education and Sports: 60th Anniversary R.E.E.F.D. 1949–2009. Rev. Española Educ. Física Deportes 2010, 15, 9–42. Available online: http://www.reefd.es/index.php/reefd/article/view/274/265 (accessed on 3 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Perrino, M.; Pedraz, V. Olympism in Citius, Altius, Fortius Magazine (1959–1976): The Beginnings of Criticism of the Olympic Movement in Spain. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2018, 34, 177–182. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M.A. El nacimiento de la prensa azul. Historia 16 1977, 9, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano, F. The Structure of the Daily Press in Spain during Francoism. Investig. Históricas Época Mod. Contemp. 1997, 17, 315–340. Available online: https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10630/11297/LeyFragaMálaga.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Sainz de Baranda, C. Women and Sport in the Media: A Study of Spanish Sports Press (1979–2010). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain, 2013. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Toro, C. History of Marca. 70th Anniversary; La Esfera de los Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2008. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Murelaga-Ibarra, J. Contextualized History of Spanish Radio under Francoism (1940–1960). Hist. Comun. Soc. 2009, 14, 367–386. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/HICS/article/view/HICS0909110367A (accessed on 12 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Rodríguez Gómez, A.A.; Fernández Vázquez, J.J. The Image of Spain through Sports and Its Protocol. EmásF Rev. Digit. Educ. Física 2012, 15, 21–33. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bonaut, J. Televised Football Broadcasts in Spain: A Historical Perspective of a Relationship of Necessity (1956–1988). Hist. Comun. Soc. 2012, 17, 249–268. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, E. Broadcasting in Spain: Legal Aspects and Positive Law; EUNSA: Pamplona, Spain, 1976. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bonaut, J.; Ojer, T. Sports Programming on Francoist Television: The Conquest of Quality through Innovation. Anàlisi Quad. Comun. Cult. 2012, 46, 69–87. Available online: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Analisi/article/view/261720 (accessed on 12 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Baget, J. History of Television in Spain: 1956–1975; FeedBack Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carr, R. Spain 1808–1975; Editorial Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1982. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carr, R. Carrero: The Grey Eminence of Franco’s Regime; Temas de Hoy: Madrid, Spain, 1993. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Froix, J.S. Football: The Ultimate Leisure Activity for Spaniards under Francoism (1939–Early 1960s). In Ocio y Ocios. Du Loisir Aux Loisirs (Espagne XVIIe–XXe Siècles); Salaün, S., Étienvre, F., Eds.; Centre de Recherche sur l’Espagne Contemporaine (CREC): Paris, France, 2006; pp. 40–65. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, A.; Rodríguez, G. School Championships in Spain: A Brief Historical Synthesis. Mater. Hist. Deporte 2009, 7, 23–34. Available online: https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/materiales_historia_deporte/article/view/508 (accessed on 12 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Pastor-Ruiz, F. History of School Sports in the Historical Territory of Bizkaia. 2002. Available online: https://www.bizkaia.eus/Kultura/kirolak/pdf/ca_Historia%20del%20deporte%20escolar%20en%20Bizkaia.pdf?hash=ca73f88f1f2818854c156e671c117063&idioma=CA (accessed on 21 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Ramírez-Macías, G. Autarkic Francoism, Women, and Physical Education. Soc. Educ. Hist. 2014, 3, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, F.; Cabeza, J. Bloomers and Medals: The Representation of Women’s Sport in NO-DO (1943–1975). Hist. Comun. Soc. 2012, 17, 195–216. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C. Sport and social movements: Lilí Álvarez in Franco’s Spain. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2019, 54, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-García, P. The University Sports System in Spain from the Perspective of Stakeholders in Sport. Towards a Successful Management and Organization Model. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Camilo José Cela, Madrid, Spain, 2018. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-García, P. Madrid-72: Diplomatic Relations and Olympic Games during Francoism. Rev. Mov. 2013, 1, 221–240. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=115325713012 (accessed on 21 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Castejón, B.; García, J.D.; Rodríguez, J. Rationalising Sports Policies; Manhattan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1973. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED087701.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Cagigal, J.M. Men and Sport; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 1957. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Cagigal, J.M. Evolution of Sport for All in Spain. Rev. Española Educ. Física Deportes 2014, 406, 9–11. Available online: http://www.reefd.es/index.php/reefd/article/view/22/24 (accessed on 24 March 2024). (In Spanish).

- Rodríguez Martínez, S. NO-DO, Social Catechism of an Era; Editorial Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Paz, M.A.; Martínez, L. New Programs for New Realities: Children’s and Youth Programming on TVE (1969–1975). J. Span. Cult. Stud. 2013, 14, 291–306. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).