Verification of Microprobe Calibration Based on Actual Diameter Measurement of the Probe Tip Sphere

Abstract

1. Introduction

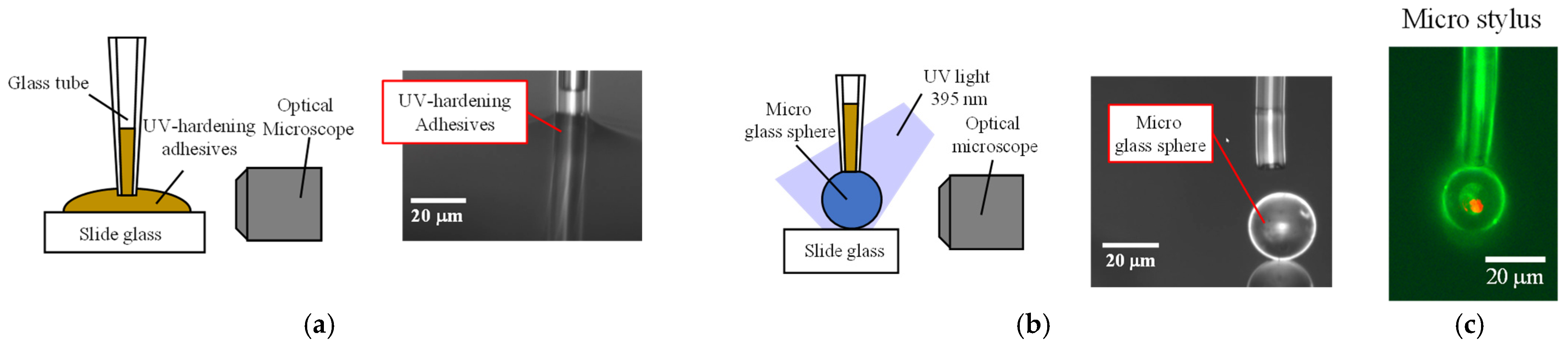

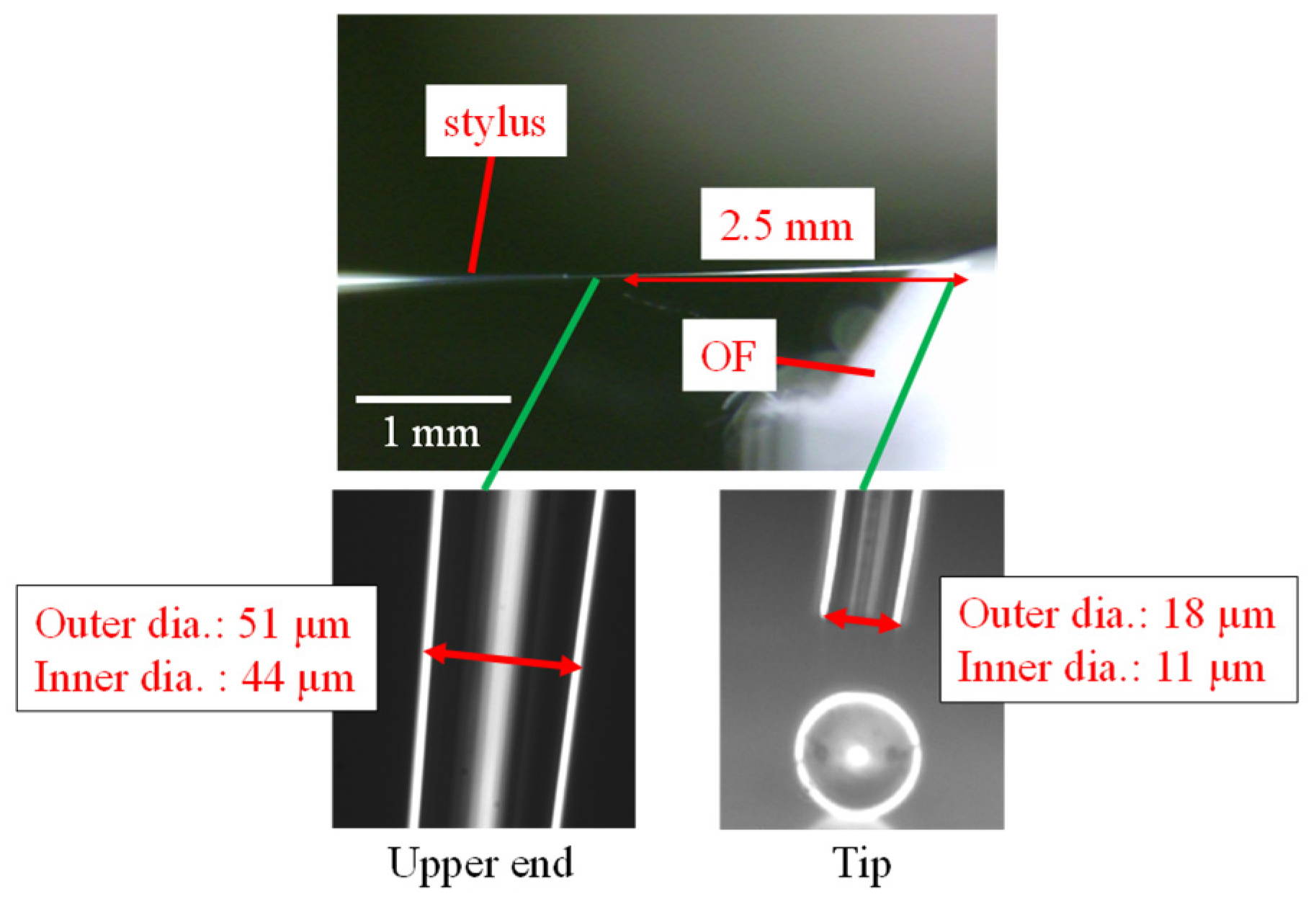

2. Fabrication of Stylus with a Micro-Tip Sphere

3. Actual Diameter Measurement Using a Contour Measuring Instrument

3.1. Principle and Methodology of Actual Diameter Measurement

3.2. Estimation of Contact Force and Deformation

3.3. Actual Diameter Measurement and Uncertainty Analysis

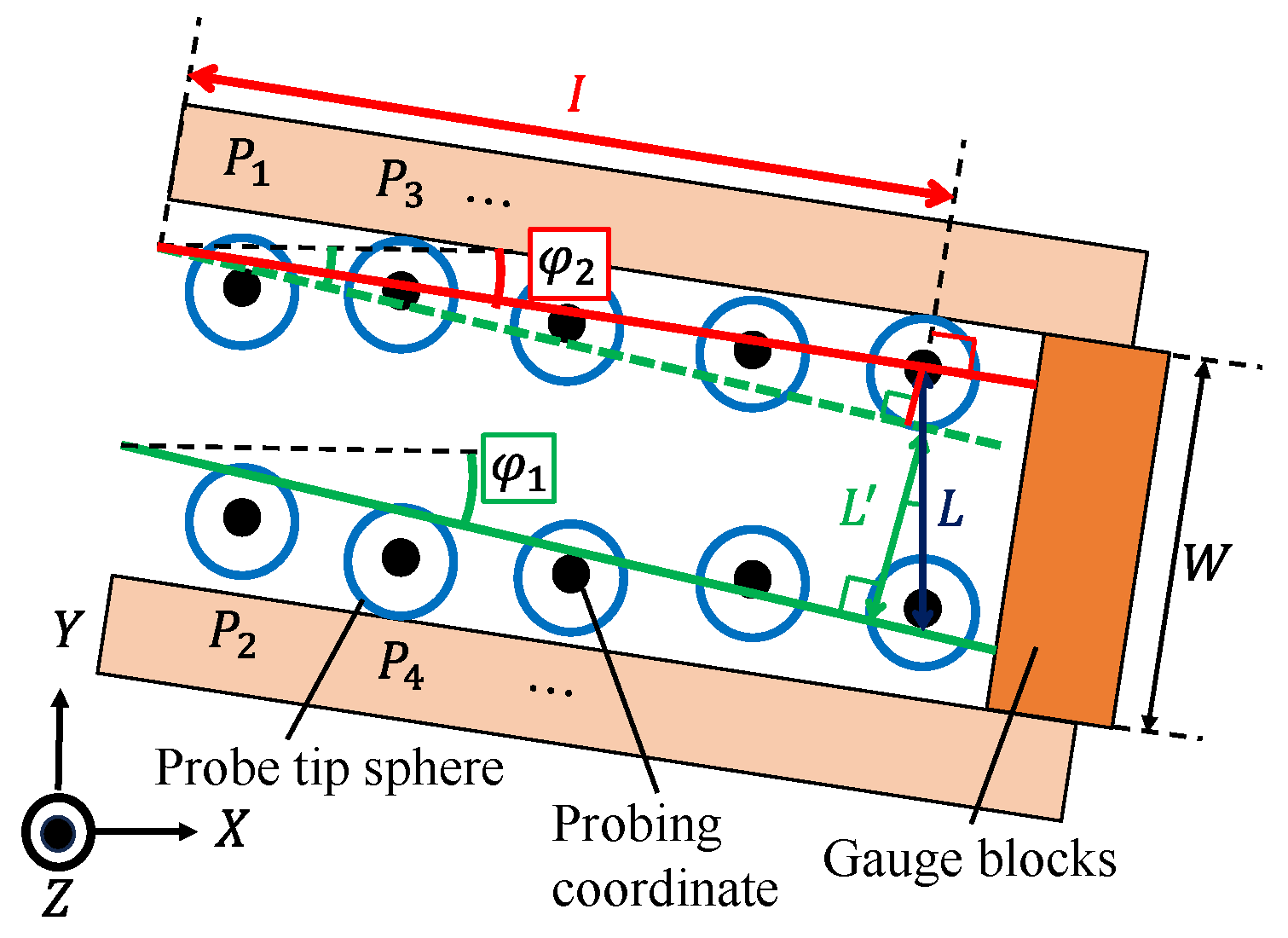

4. Effective Diameter Measurement Using a Precision Micro-Slit

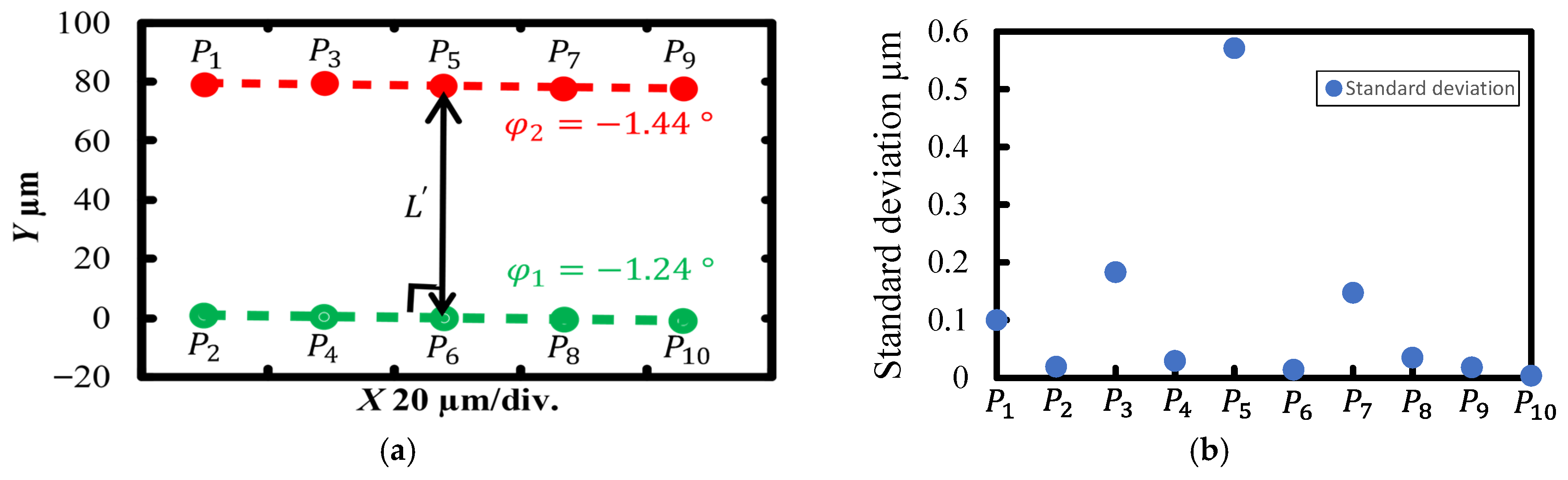

4.1. Principle and Methodology of Effective Diameter Measurement

4.2. Effective Diameter Measurement and Uncertainty Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takamasu, K.; Ozawa, S.; Asano, T.; Suzuki, R.; Furutani, R.; Ozono, S. Basic Concepts of Nano-CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machine with Nanometer Resolution). In Proceedings of the 1996 The Japan-China Bilateral Symposium on Advanced Manufacturing Engineering, Kanagawa, Japan, 4 October 1996; pp. 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Michihata, M. Surface-Sensing Principle of Microprobe System for Micro-Scale Coordinate Metrology: A Review. Metrology 2022, 2, 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.C.; Fei, Y.T.; Yu, X.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Wang, W.L.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.S. Development of a low-cost micro-CMM for 3D micro/nano measurements. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckenmann, A.; Estler, T.; Peggs, G.; McMurtry, D. Probing Systems in Dimensional Metrology. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2004, 53, 657–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverley, J.D.; Leach, R.K. A review of the existing performance verification infrastructure for micro-CMMs. Precis. Eng. 2015, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, M.; Ito, S.; Kato, D.; Matsumoto, K.; Kamiya, K. Investigation of probing repeatability inside a micro-hole by changing probe approach direction for a local surface interaction force detection type microprobe. Front. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 3, 1104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Katsuki, A.; Sajima, T.; Suematsu, T. Study of a vibrating fiber probing system for 3-D micro-structures: Performance improvement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 094010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Brand, U.; Kleine-Besten, T.; Hoffmann, W.; Schwenke, H.; Bütefisch, S.; Büttgenbach, S. Recent developments in dimensional metrology for microsystem components. Microsyst. Technol. 2002, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Chen, Y.L.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W.; Takahashi, T.; Toshihiko, K.; Kunmei, A.; Atsushi, H. A Micro-Coordinate Measurement Machine (CMM) for Large-Scale Dimensional Measurement of Micro-Slits. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Xiang, M.; He, Y.X.; Fan, K.C.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Huang, Q.X.; Zhou, B. Development of a High-Precision Touch-Trigger Probe Using a Single Sensor. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, D.; Claverley, J.; Leach, R. Chapter 9—Coordinate Metrology. In Fundamental Principles of Engineering Nanometrology, 2nd ed.; A Volume in Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 295–325. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10360-5:2020; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS), Part 5: Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) Using Single and Multiple Stylus Contacting Probing Systems Using Discrete Point and/or Scanning Measuring Mode. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Mitutoyo Corporation. Coordinate Measuring Machine Probe Accessories, E16005. Available online: https://www2.mitutoyo.co.jp/eng/support/service/catalog/01/E16005.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Chen, Y.L.; Ito, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Kobayashi, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W. On-line qualification of a micro probing system for precision length measurement of micro-features on precision parts. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 074008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Shimizu, Y.; Kikuchi, H.; Gao, W.; Takahashi, K.; Kanayama, T.; Arakawa, K.; Hayashi, A. Uncertainty analysis of slot die coater gap width measurement by using a shear mode micro-probing system. Precis. Eng. 2016, 43, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küng, A.; Meli, F.; Thalmann, R. Ultraprecision micro-CMM using a low force 3D touch problem. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, R.; Meli, F.; Küng, A. State of the Art of Tactile Micro Coordinate Metrology. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawabe, M.; Maeda, F.; Yamaryo, Y.; Simomura, T.; Saruki, Y.; Kubo, T.; Sakai, H.; Aoyagi, S. A new vacuum interferometric comparator for calibrating the fine linear encoders and scales. Precis. Eng. 2004, 28, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.; Friedrich, H.; Fujii, K.; Giardini, W.; Mana, G.; Picard, A.; Pohl, H.J.; Riemann, H.; Valkiers, S. The Avogadro constant determination via enriched silicon-28. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 092002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, B.; Azuma, Y.; Bartl, G.; Becker, P.; Bettin, H.; Borys, M.; Busch, I.; Fuchs, P.; Fujii, K.; Fujimoto, H.; et al. Counting the atoms in a 28Si crystal for a new kilogram definition. Metrologia 2011, 48, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesmann, U.; Soons, J.; Wang, Q.; Debra, D. Measuring Form and Radius of Spheres with Interferometry. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2004, 53, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.L.; Evans, C.J.; Davies, A.; Estler, W.T. Displacement Uncertainty in Interferometric Radius Measurements. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2002, 51, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, G.; Krystek, M.; Nicolaus, A. PTB’s enhanced stitching approach for the high-accuracy interferometric form error characterization of spheres. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 064002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, G.; Krystek, M.; Nicolaus, A.; Giardini, W. Interferometric determination of the topographies of absolute sphere radii using the sphere interferometer of PTB. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michihata, M.; Hayashi, T.; Adachi, A.; Takaya, Y. Measurement of probe-stylus sphere diameter for micro-CMM based on spectral fingerprint of whispering gallery modes. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2014, 63, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Michihata, M.; Zhao, Z.; Chu, B.; Takamasu, K.; Takahashi, S. Radial mode number identification on whispering gallery mode resonances for diameter measurement of microsphere. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2019, 30, 065201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Shima, Y.; Kato, D.; Matsumoto, K.; Kamiya, K. Development of a Microprobing System for Side Wall Detection Based on Local Surface Interaction Force Detection. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2020, 14, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. Chapter 7—Precision Nanometrology: Sensors and Measuring Systems for Nanomanufacturing; Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 211–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Kodama, I.; Gao, W. Development of a probing system for a micro-coordinate measuring machine by utilizing shear-force detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 064011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Nose, A.; Suzuki, H.; Okada, M. Cutting Tool Edge and Textured Surface Measurements with a Point Autofocus Probe. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2017, 11, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 25178-605:2014; Geometrical Product Specification (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal—Part 605: Nominal Characteristics of Non-Contact (Point Autofocus Probe) Instruments. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Iwata, F.; Sumiya, Y.; Sasaki, A. Nanometer-Scale Metal Plating Using a Scanning Shear-Force Microscope with an Electrolyte-Filled Micropipette Probe. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 43, 4482–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, Y.; Urahama, S.; Murakami, M.; Iwata, F. The use of capillary force for fabricating probe tips for scattering-type near-field scanning optical microscopes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 1598–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCGM 100:2008; Evaluation of Measurement Data–Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM). Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology: Sèvres, France, 2008.

- ISO 3650:1998; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Length Standards—Gauge Blocks. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Doriton, T.; Beers, J. The Gauge Block Handbook; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2014; pp. 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Goj, B.; Dressler, L.; Hoffmann, M. Semi-contact measurements of three-dimensional surfaces utilizing a resonant uniaxial microprobe. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 064012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIOS Meßtechnik GmbH. Available online: https://www.sios-precision.com/en/products/nanopositioning-and-nanomeasuring-machine-nmm-1 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Angle (°) | 0 | 45 | 90 | 135 | 180 | 225 | 270 | 315 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average diameter | 21.326 | 21.352 | 21.422 | 21.362 | 21.299 | 21.342 | 21.413 | 21.386 | 21.362 |

| Standard deviation | 0.133 | 0.092 | 0.142 | 0.146 | 0.014 | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.016 | - |

| Source of Uncertainty | Symbol | Value | Type | Distribution | Divisor | Sensitivity Coefficient | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-directional resolution of NH-3s | 1 | B | Rectangular | 0.3 | |||

| Z-directional accuracy of NH-3s | 227 | B | Rectangular | 65.5 | |||

| Repeatability of diameter measurement | 146 | A | 65.3 | ||||

| Effect of temperature variation to tip sphere diameter | 0.5 °C | B | Rectangular | 0.07 (nm/K) | 0.02 | ||

| Accuracy of average height of the OF surface | 70 | A | 1 | 70 | |||

| Combined standard uncertainty | 116.0 | ||||||

| Expanded uncertainty | () | 232.0 |

| Angle (°) | 0 | 45 | 90 | 135 | 180 | 225 | 270 | 315 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 67 | 13 | 52 | 70 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 25 |

| Minimum | 11 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Average | Maximum | Minimum | Max-Min |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21.45 | 21.58 | 21.32 | 0.26 |

| Source of Uncertainty | Symbol | Value | Type | Distribution | Divisor | Sensitivity Coefficient | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined standard uncertainty of micro-slit gap width | 78.6 | ||||||

| Parallelism of both sides of the micro-slit inner walls | 260 | B | Rectangular | 75.1 | |||

| Flatness inside the upper slit | 50 | B | Rectangular | 14.4 | |||

| Flatness inside the lower slit | 50 | B | Rectangular | 14.4 | |||

| Micro-slit gap width error due to wringing of the gauge blocks (Wringing error (double side)) | 20 | B | Rectangular | 11.5 | |||

| Thermal effect to the center gauge block | 0.5 °C | B | Rectangular | 1.08 (nm/K) | 0.3 | ||

| Combined standard uncertainty in L | 183.4 | ||||||

| Repeatability of probing | 180 | A | - | 80.5 | |||

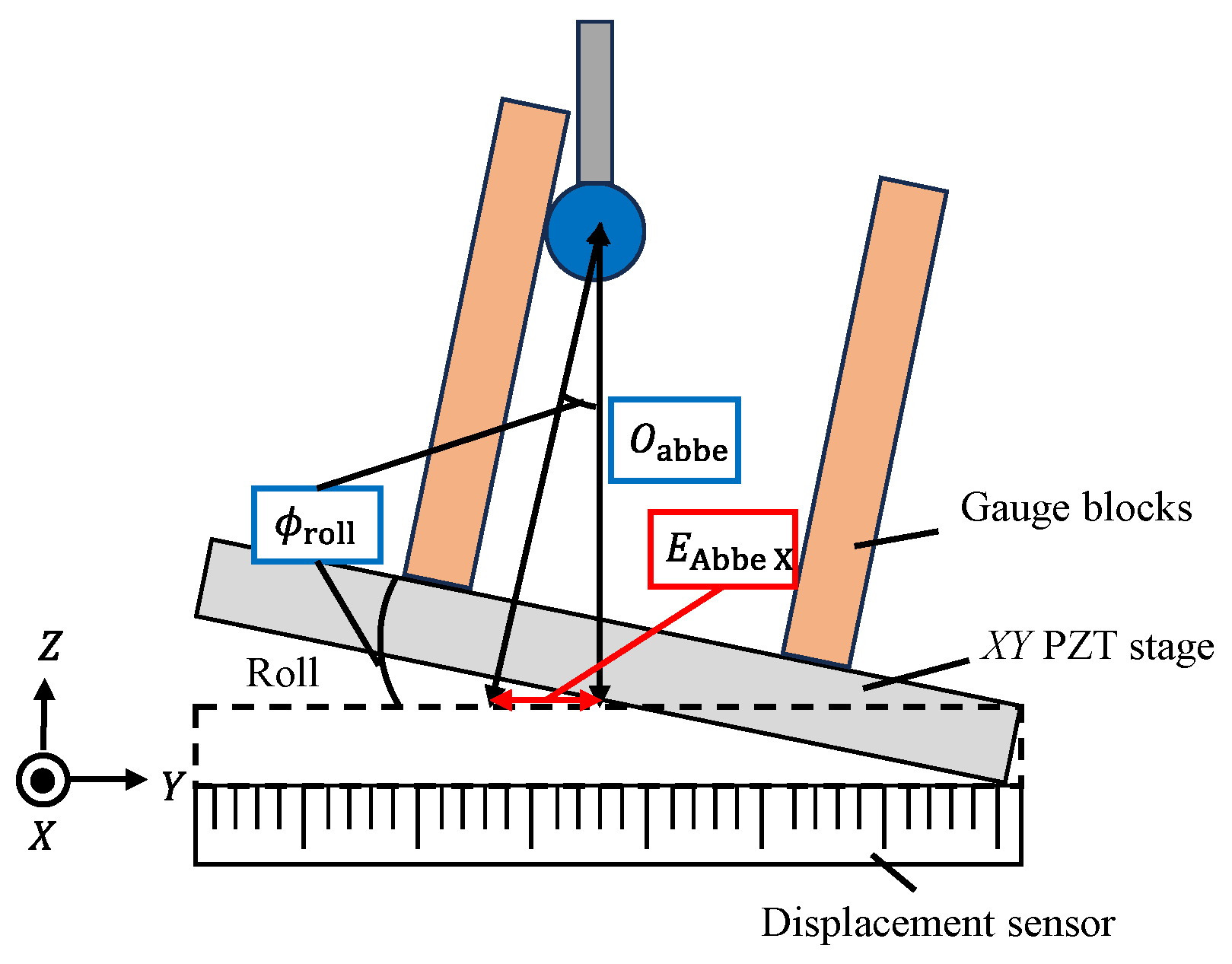

| Abbe error (rolling) | 872.7 | B | Rectangular | 251.9 | |||

| Abbe error (pitching) | 17.4 | B | Rectangular | 5.0 | |||

| Abbe error (yawing) | 2.9 × 10−5 | B | Rectangular | 8.5 × 10−6 | |||

| Thermal effect on the probe tip sphere | 0.5 °C | B | Rectangular | 0.07 (nm/K) | 0.02 | ||

| Combined standard uncertainty | 276.0 | ||||||

| Expanded uncertainty | () | 551.9 |

| Average (μm) | Repeatability (nm) | Uncertainty (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21.362 | 146 | 232.0 | |

| 21.45 | 180 | 551.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ito, S.; Inukai, D.; Tomioka, T.; Sugisawa, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Kamiya, K. Verification of Microprobe Calibration Based on Actual Diameter Measurement of the Probe Tip Sphere. Metrology 2025, 5, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040073

Ito S, Inukai D, Tomioka T, Sugisawa Y, Matsumoto K, Kamiya K. Verification of Microprobe Calibration Based on Actual Diameter Measurement of the Probe Tip Sphere. Metrology. 2025; 5(4):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040073

Chicago/Turabian StyleIto, So, Daichi Inukai, Takehiro Tomioka, Yasutomo Sugisawa, Kenta Matsumoto, and Kazuhide Kamiya. 2025. "Verification of Microprobe Calibration Based on Actual Diameter Measurement of the Probe Tip Sphere" Metrology 5, no. 4: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040073

APA StyleIto, S., Inukai, D., Tomioka, T., Sugisawa, Y., Matsumoto, K., & Kamiya, K. (2025). Verification of Microprobe Calibration Based on Actual Diameter Measurement of the Probe Tip Sphere. Metrology, 5(4), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040073