Clustering of Civil Aviation Occurrences in Brazil: Operational Patterns and Critical Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Tools

2.3. Data Preparation

2.4. Clustering Methods

2.4.1. K-Means

- Initialization: k observations are randomly selected as the initial centroids;

- Assignment: each remaining point is assigned to the cluster with the nearest centroid, calculated using Euclidean distance;

- Update: after assignment, the centroid of each cluster is recalculated as the mean of all its observations.

2.4.2. Hierarchical Clustering

2.4.3. K-Medoids

- Build phase: k medoids are selected step by step, choosing points that reduce overall dissimilarity;

- Swap phase: each medoid is tested against non-medoid points. If a swap reduces the total dissimilarity, it is kept. This continues until no further improvement is possible, and the clusters are stable.

2.5. Cluster Validation

3. Results

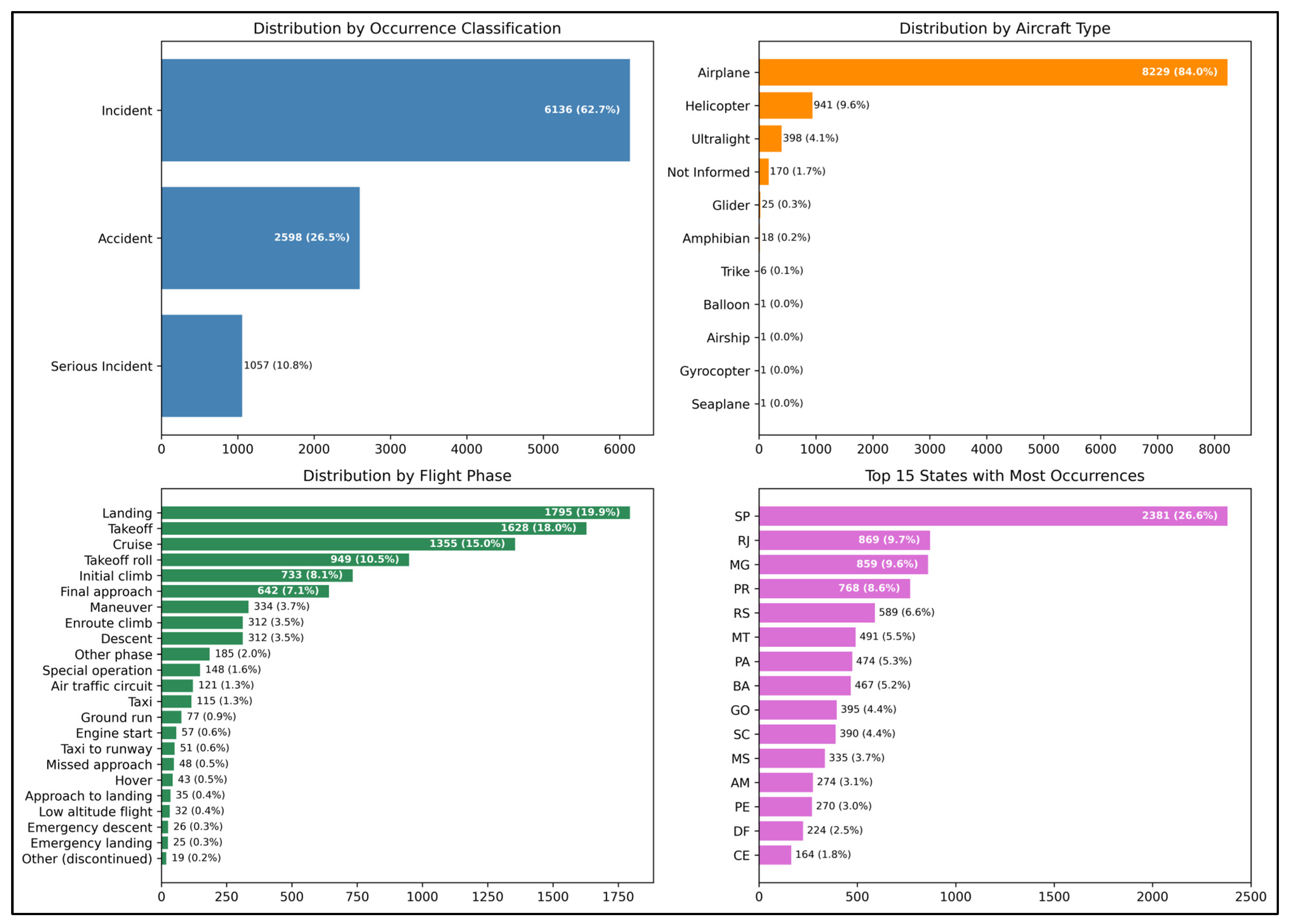

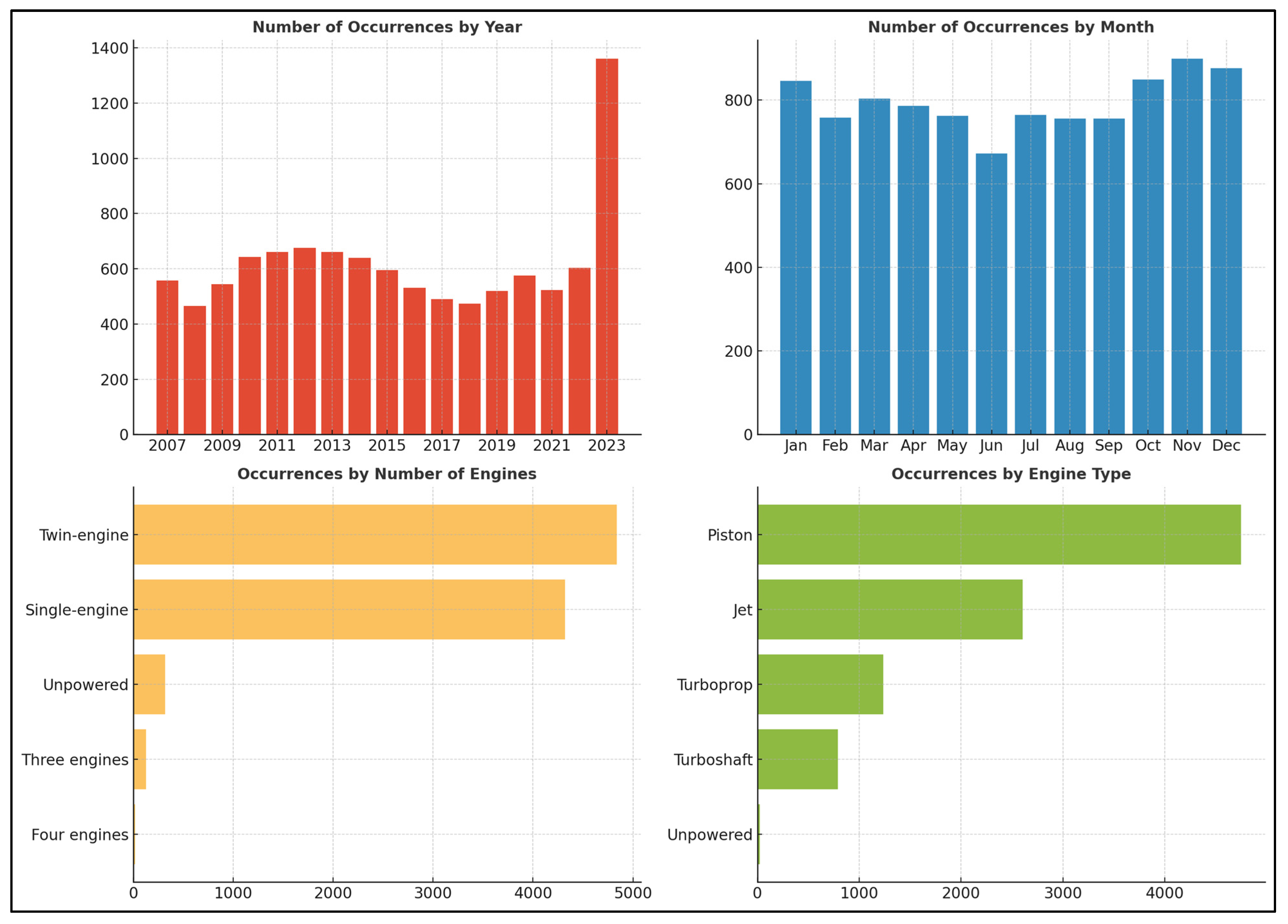

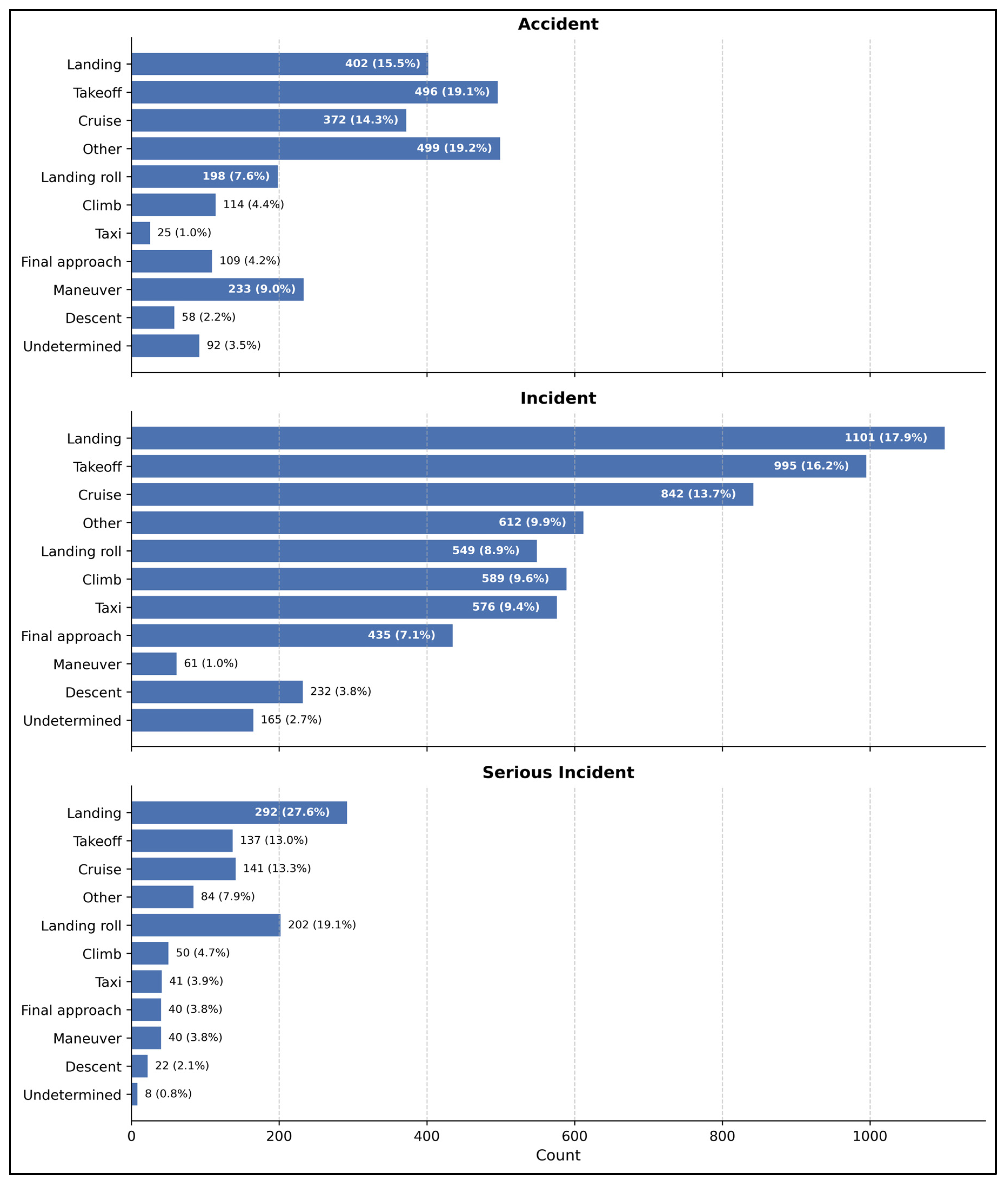

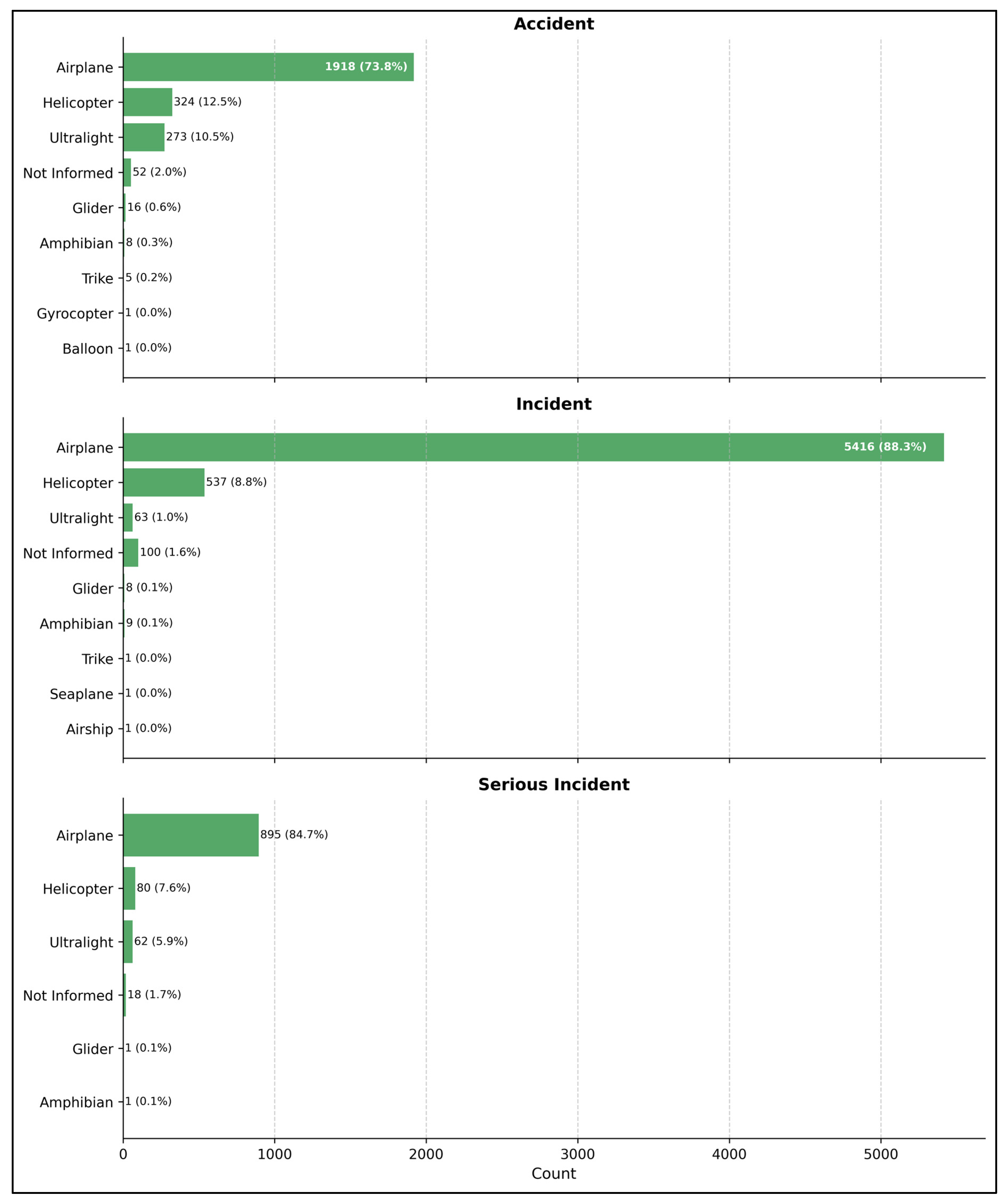

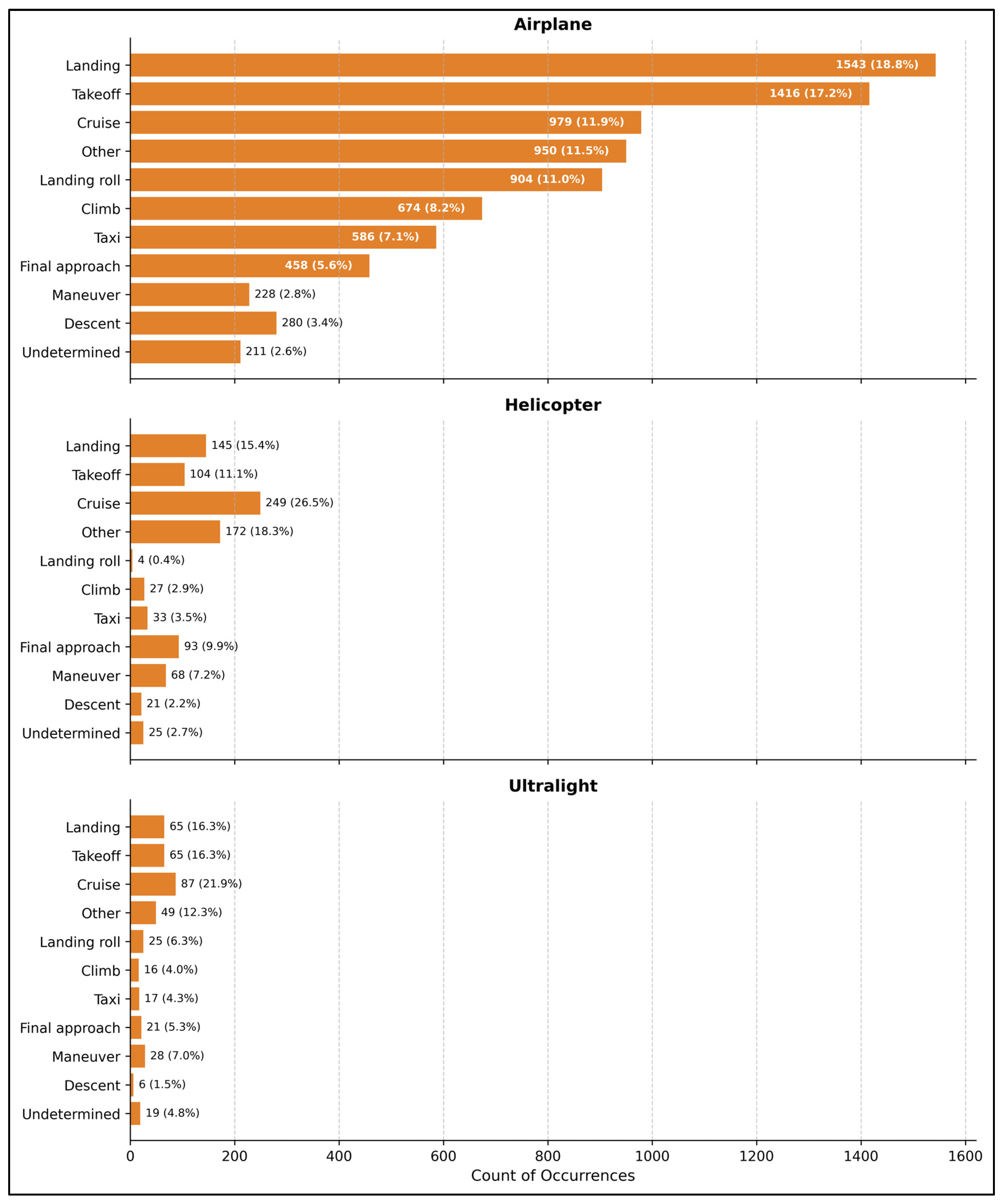

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

3.2. Clustering

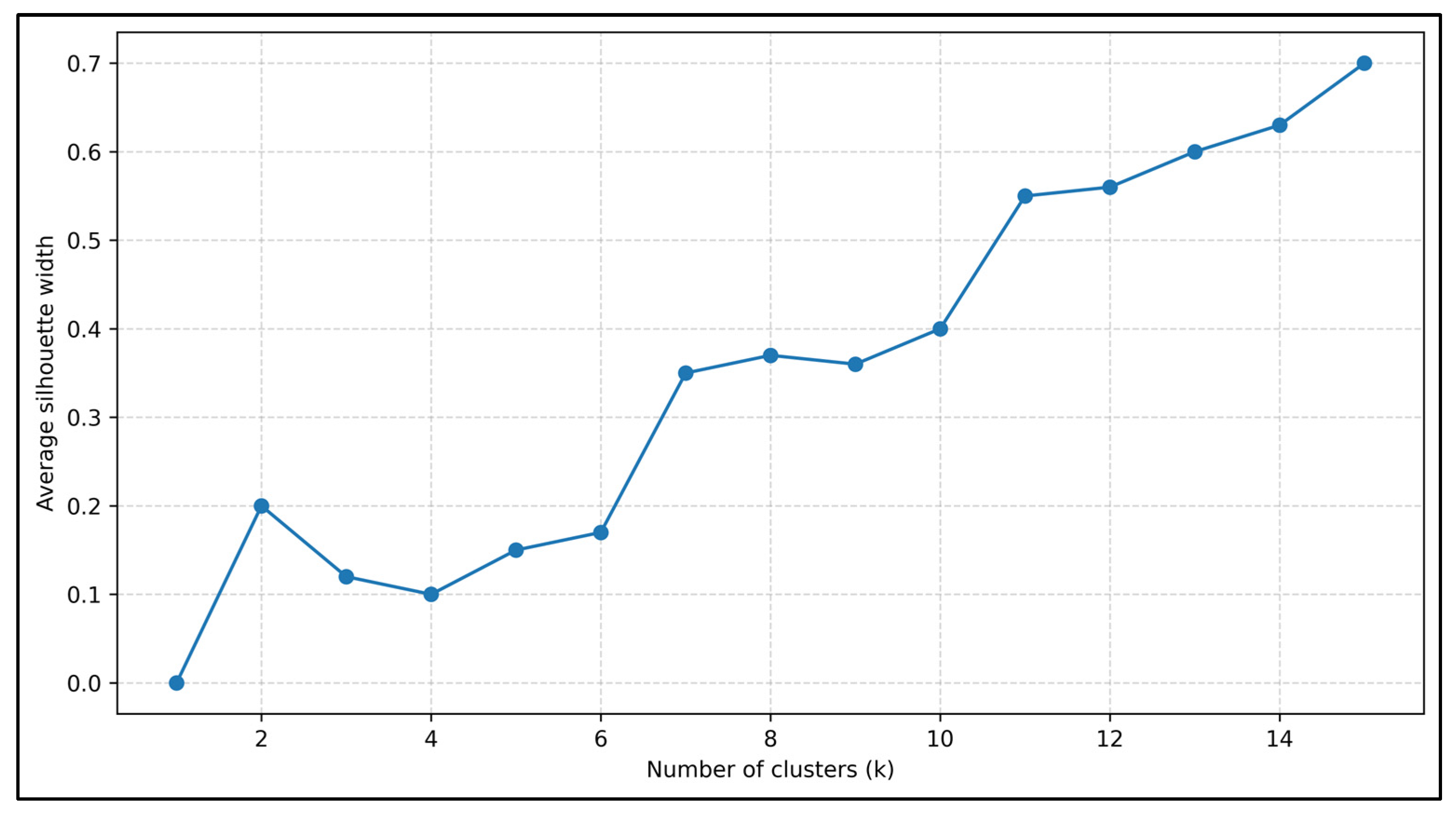

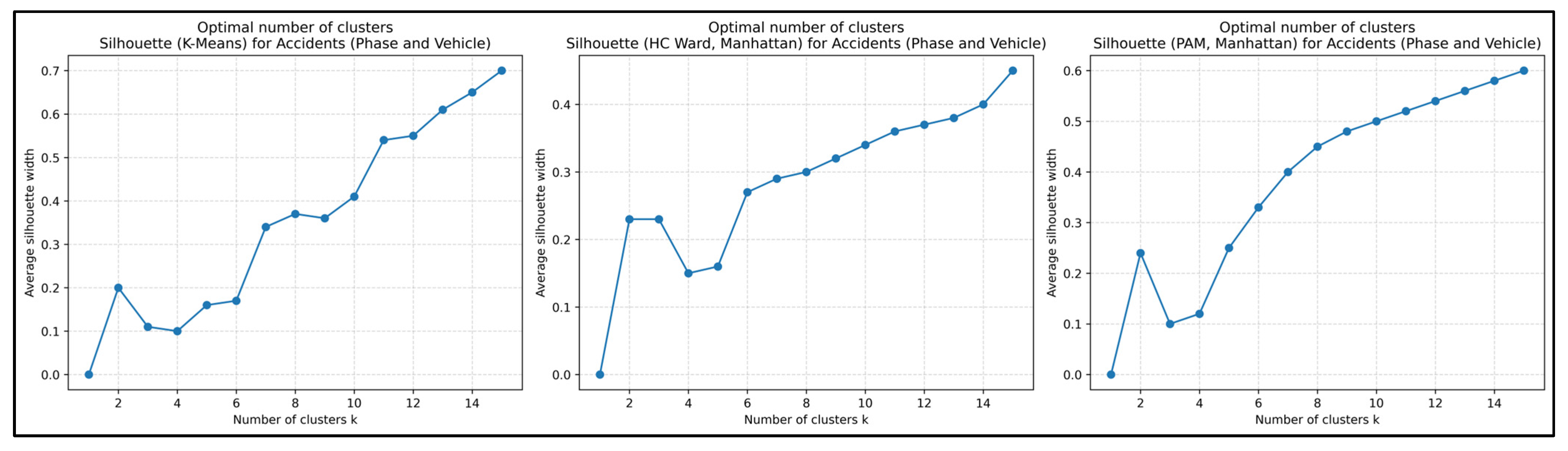

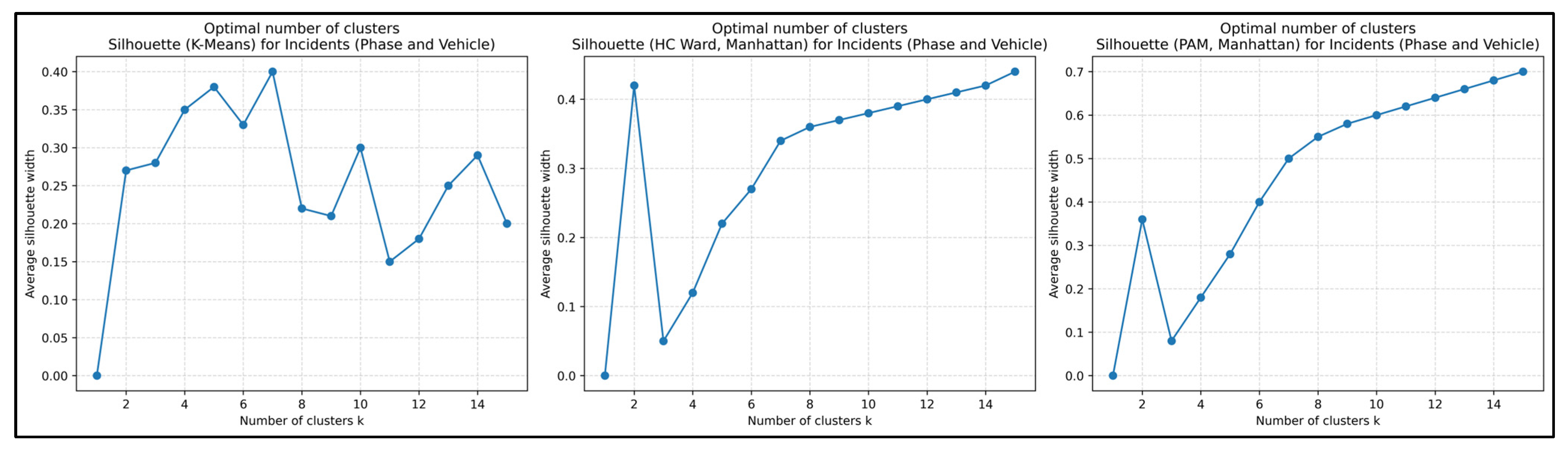

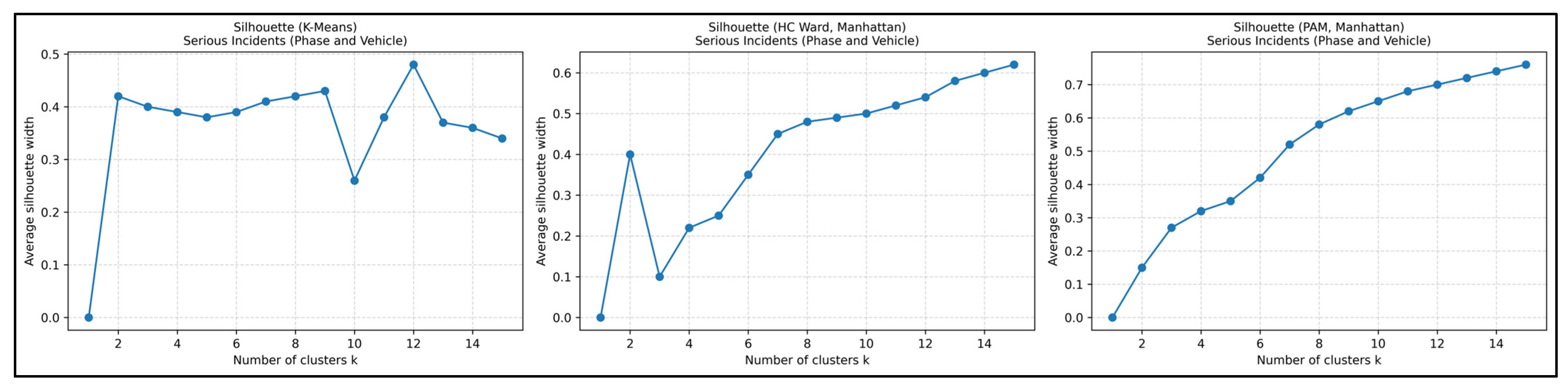

3.2.1. Two Variables

3.2.2. Three Variables

- Helicopters;

- Ultralights;

- Takeoff;

- Landing;

- Cruise;

- Maneuver;

- Landing roll;

- Specialized operations;

- Other fixed-wing phases.

- Helicopters;

- Takeoff;

- Landing;

- Cruise;

- Landing roll;

- Taxi;

- Other fixed-wing phases.

- Helicopters;

- Ultralights;

- Takeoff;

- Landing;

- Cruise;

- Landing roll;

- Other fixed-wing phases.

4. Discussion

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

4.2. Clustering Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brazilian National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC). ANAC Consumer Bulletin 2024; ANAC: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anac/pt-br/noticias/2025/anac-divulga-boletim-do-consumidor-2024/BoletimANACConsumidor2024Final.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- International Air Transport Association (IATA). Strengthened Profitability Expected in 2025 Even as Supply Chain Issues Persist; IATA Press Release: Montreal, QC, Canada; Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2024-releases/2024-12-10-01/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). State of Global Aviation Safety. ICAO Safety Report 2025 Edition; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://www.icao.int/safety/pages/safety-report.aspx (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- BOEING. Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents: Worldwide Operations, 1959–2024, 56th ed.; Boeing Commercial Airplanes: Seattle, WA, USA, 2025; 34p, Available online: https://www.boeing.com/content/dam/boeing/boeingdotcom/company/about_bca/pdf/statsum.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Shappell, S.A. A Human Error Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents Using the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS). Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2001, 72, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leveson, N. Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, P.; Cornelissen, M.; Trotter, M. Systems-Based Accident Analysis Methods: A Comparison of Accimap, HFACS, and STAMP. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netjasov, F.; Janić, M. A Review of Research on Risk and Safety Modelling in Civil Aviation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2008, 14, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen, A.L.C.; Lin, P.H.; Hale, A.R. Accident Models and Organisational Factors in Air Safety: The Need for Multi-Method Models. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čokorilo, O.; De Luca, M.; Dell’Acqua, G. Aircraft Safety Analysis Using Clustering Algorithms. J. Risk Res. 2014, 17, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; He, F.; Li, L.; Xiao, G. An Adaptive Online Learning Model for Flight Data Cluster Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/AIAA 37th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), London, UK, 23–27 September 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, L.; Alam, S.; Wang, Y. An Incremental Clustering Method for Anomaly Detection in Flight Data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharoufah, H.; Murray, J.; Baxter, G.; Wild, G. A Review of Human Factors Causations in Commercial Air Transport Accidents and Incidents: From 2000 to 2016. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, R.; Iqbal, M.D.; Buchari, M.A.; Veny, H. Analysis of Commercial Airplane Accidents Worldwide Using K-Means Clustering. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2023, 13, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasra, S.K.; Valentino, G.; Muscat, A.; Camilleri, R. A Comparative Study of Unsupervised Machine Learning Methods for Anomaly Detection in Flight Data: Case Studies from Real-World Flight Operations. Aerospace 2025, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, R.; Iqbal, M.D.; Buchari, M.A.; Veny, H. Using the Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering Method to Examine Human Factors in Indonesian Aviation Accidents. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Annex 13—Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation, 11th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016; Available online: https://www.icao.int/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Brazilian Aeronautical Accidents Investigation and Prevention Center (CENIPA). Aeronautical Occurrences in Brazilian Civil Aviation (2007–2023); Open Data Portal, Brazilian Government: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://dados.gov.br/dados/conjuntos-dados/ocorrencias-aeronauticas-da-aviacao-civil-brasileira (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Han, J.; Kamber, M.; Pei, J. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras & TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC). Brazilian Aeronautical Registry: Open Data; ANAC: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anac/pt-br/sistemas/rab/dados-abertos-rab (accessed on 6 July 2025).

| Variable Name | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|

| aircraft_damage_level | level of damage sustained by the aircraft | categorical |

| aircraft_engine_quantity | number of engines installed on the aircraft | categorical |

| aircraft_engine_type | type of aircraft engine (piston, turboprop, jet, etc.) | categorical |

| aircraft_model | model designation of the aircraft | categorical |

| aircraft_total_fatalities | total number of fatalities associated with the occurrence | categorical |

| aircraft_type | general type of aircraft (airplane, helicopter, ultralight, etc.) | categorical |

| city | city where the occurrence took place | categorical |

| contributing_factor_domain | domain or category of the contributing factor (human, operational, technical, etc.) | categorical |

| contributing_factor_name | name of the contributing factor(s) identified in the investigation | categorical |

| country | country where the occurrence took place | categorical |

| flight_phase | phase of flight at the time of the occurrence (takeoff, landing, cruise, etc.) | categorical |

| latitude | latitude coordinate of the occurrence site | numeric |

| longitude | longitude coordinate of the occurrence site | numeric |

| occurrence_category | broader operational category of the occurrence | categorical |

| occurrence_classification | classification of the event (accident, incident, serious incident) | categorical |

| occurrence_date | date of the occurrence | date |

| occurrence_id | unique identifier of the occurrence record | integer |

| occurrence_month | month of the occurrence | integer |

| occurrence_state | Brazilian state (federative unit) where the occurrence took place | categorical |

| occurrence_type | specific operational type of occurrence | categorical |

| occurrence_year | year of the occurrence | integer |

| report_number | identification number of the published investigation report | categorical |

| Cluster Label | Operational Interpretation | Likely Contributing-Factor Domain * |

|---|---|---|

| cruise 1,2,3 | system reliability; route failure; anomaly management. | technical/maintenance; (environmental) |

| helicopters 1,2,3 | mission profiles with low altitude/speed; operations in confined areas. | human/operational; (environmental) |

| landing 1,2,3 | approach stabilization; runway/wind effect; go-around decision. | human/operational; (environmental) |

| landing roll 1,2,3 | directional control; braking; runway/contamination. | human/operational; (environmental) |

| maneuver 1 | outside the standard profile; low height/sharp curves. | human/operational |

| other fixed-wing phases 1,2,3 | infrequent/undetermined situations. | operational |

| specialized operations 1 | specific mission profiles (agriculture, photography/filming, inspection). | human/operational |

| takeoff 1,2,3 | high workload; setup/briefing; takeoff performance. | human/operational |

| taxi 2 | situational awareness; signage/lighting; incursions. | human/operational |

| ultralights 1,3 | limited performance envelope; lower structural robustness; recreational aviation. | human/operational; (technical/maintenance) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santana, F.D.; Pamplona, D.A.; Habermann, M.; Kacedan, L.; Guterres, M.X. Clustering of Civil Aviation Occurrences in Brazil: Operational Patterns and Critical Contexts. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040185

Santana FD, Pamplona DA, Habermann M, Kacedan L, Guterres MX. Clustering of Civil Aviation Occurrences in Brazil: Operational Patterns and Critical Contexts. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040185

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantana, Felipe Duarte, Daniel Alberto Pamplona, Mateus Habermann, Lila Kacedan, and Marcelo Xavier Guterres. 2025. "Clustering of Civil Aviation Occurrences in Brazil: Operational Patterns and Critical Contexts" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040185

APA StyleSantana, F. D., Pamplona, D. A., Habermann, M., Kacedan, L., & Guterres, M. X. (2025). Clustering of Civil Aviation Occurrences in Brazil: Operational Patterns and Critical Contexts. Future Transportation, 5(4), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040185