Tribological Assessment of FFF-Printed TPU Under Dry Sliding Conditions for Sustainable Mobility Components

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Specimen Preparation

- 10% Infill (G10);

- 50% Infill (G50);

- 100% Infill (G100).

2.2. Tribological Testing (Ball-on-Disc)

- Counterbody (100Cr6 spherical pin): The spherical pin had a nominal dimension diameter of Ø6 mm. Its mechanical properties include a Young modulus of 205,000 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.33.

- Loading and Motion: A constant normal load of 5 N was applied. The corresponding initial maximum theoretical Hertz contact pressure generated was 231 MPa. The tangential sliding speed was maintained at 150 mm/s.

- Test geometry and duration: Each test run involved a total sliding distance of 300 m (specifically, 300.14 m recorded). This duration corresponded to approximately 5308 total cycles and a total test duration of roughly 2001 s (at an acquisition interval of 1.00 s).

- Environment: Testing was strictly conducted under dry sliding conditions, with no lubricant used. The ambient testing environment was characterized by a stable temperature of ±25 °C and a humidity of 50% r.H.

2.3. Surface Roughness and Hardness

3. Results

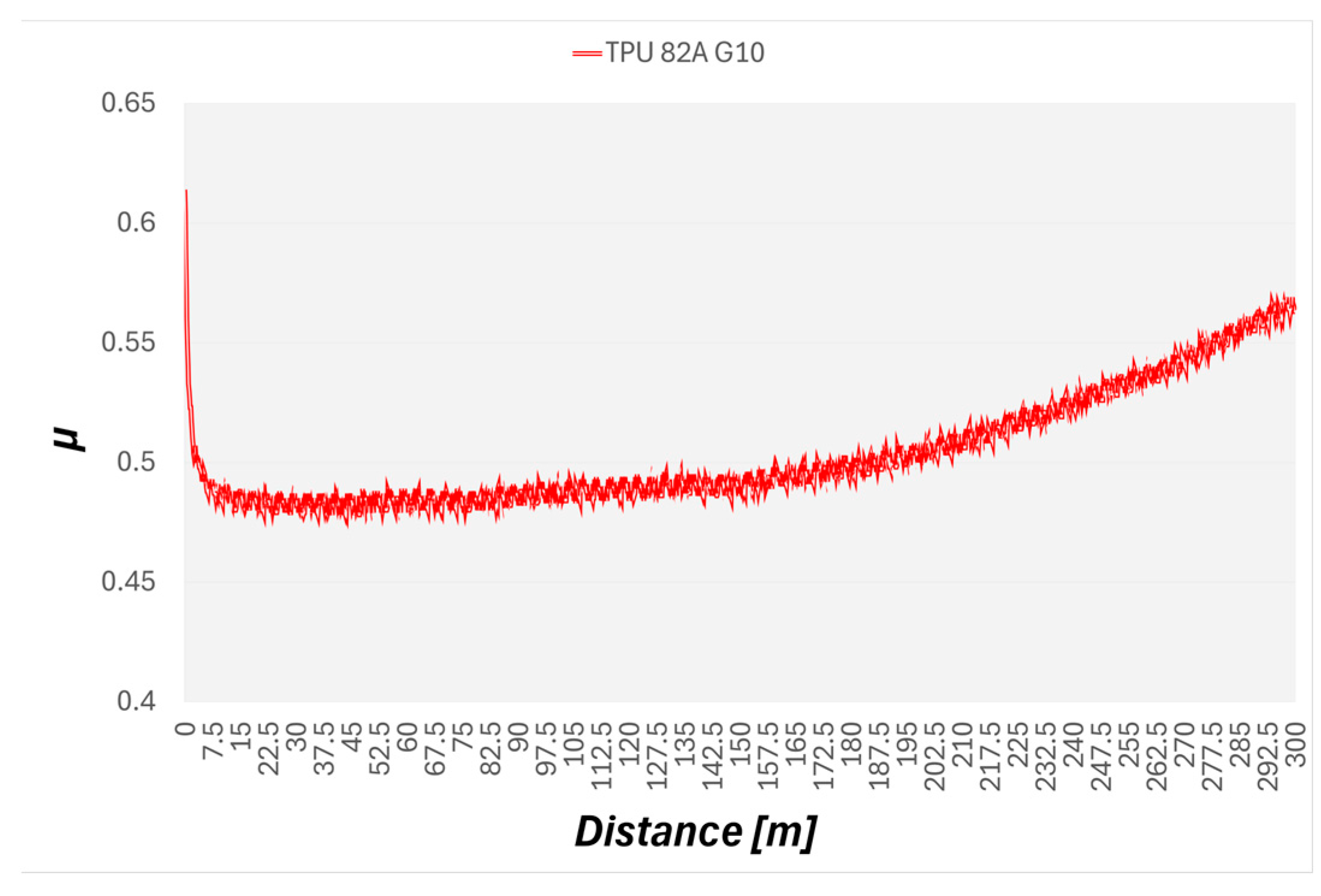

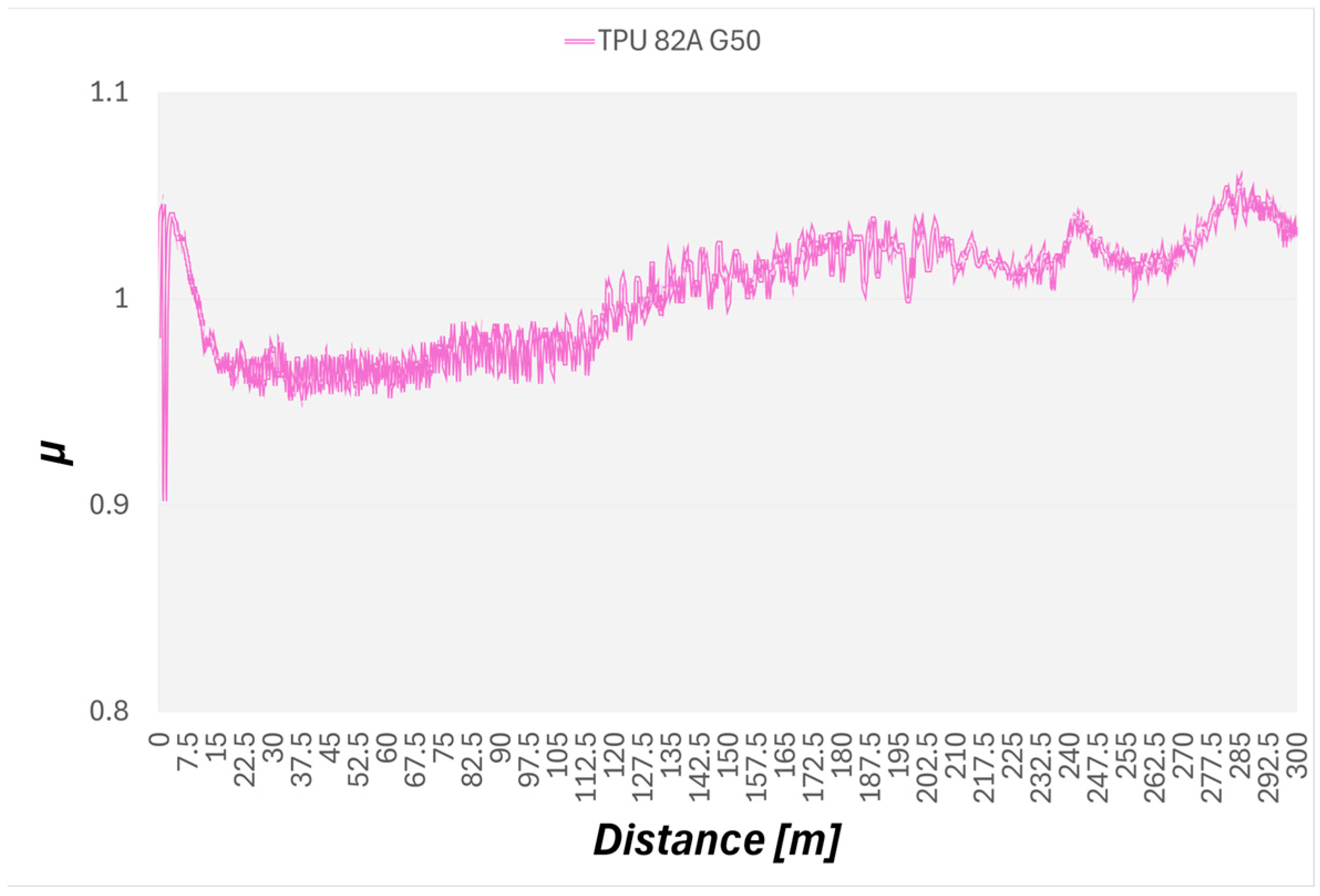

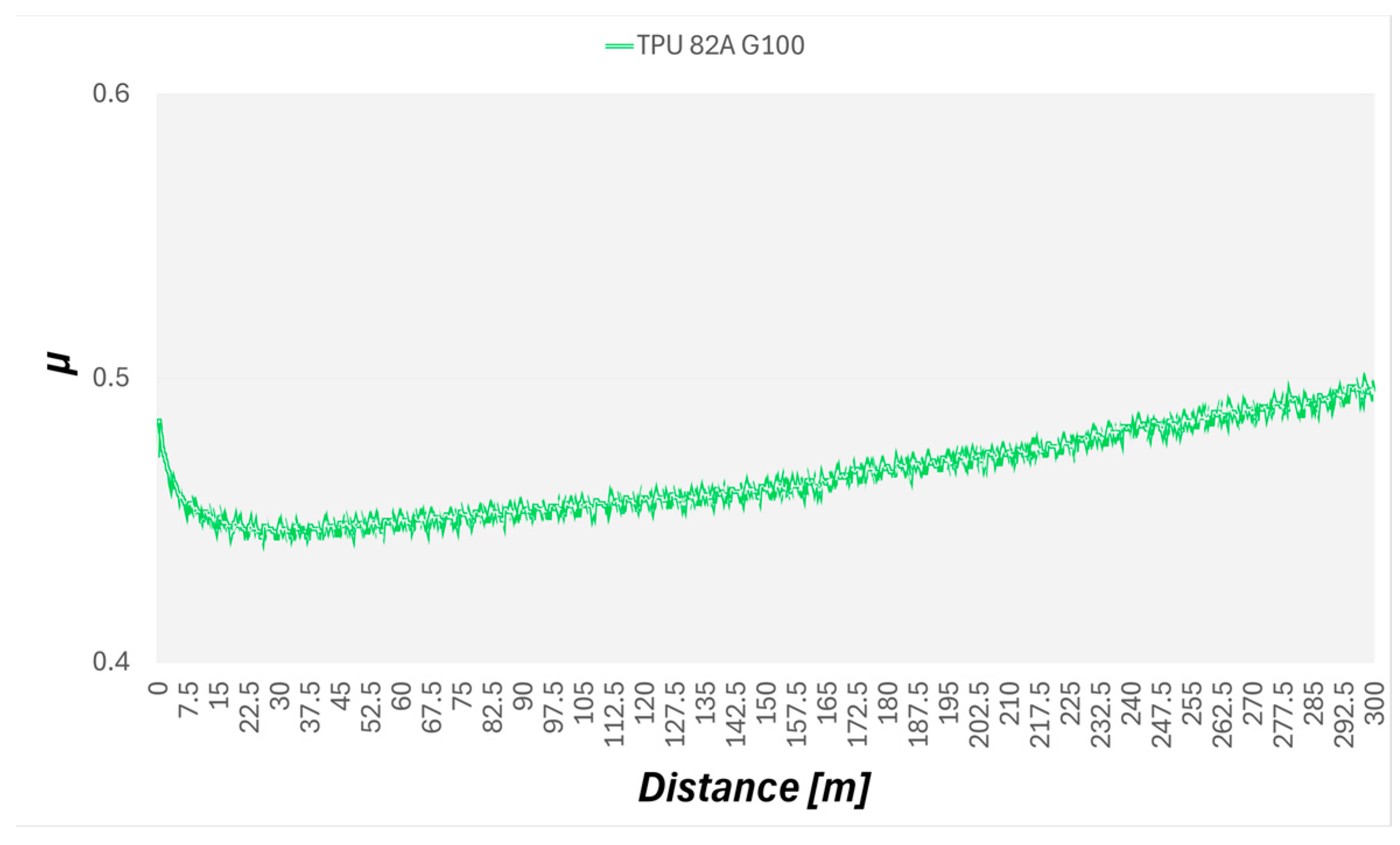

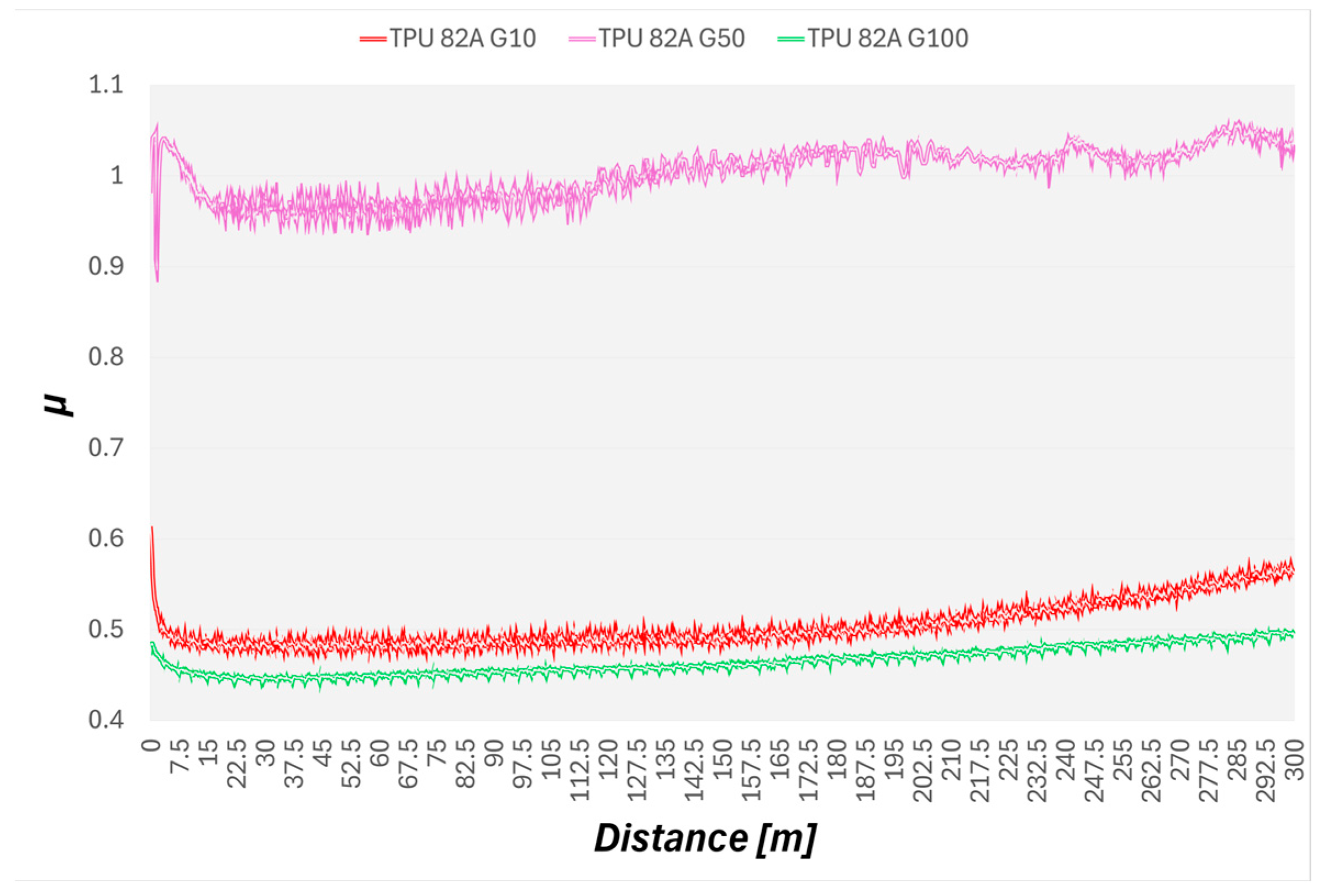

3.1. Tribological Performance

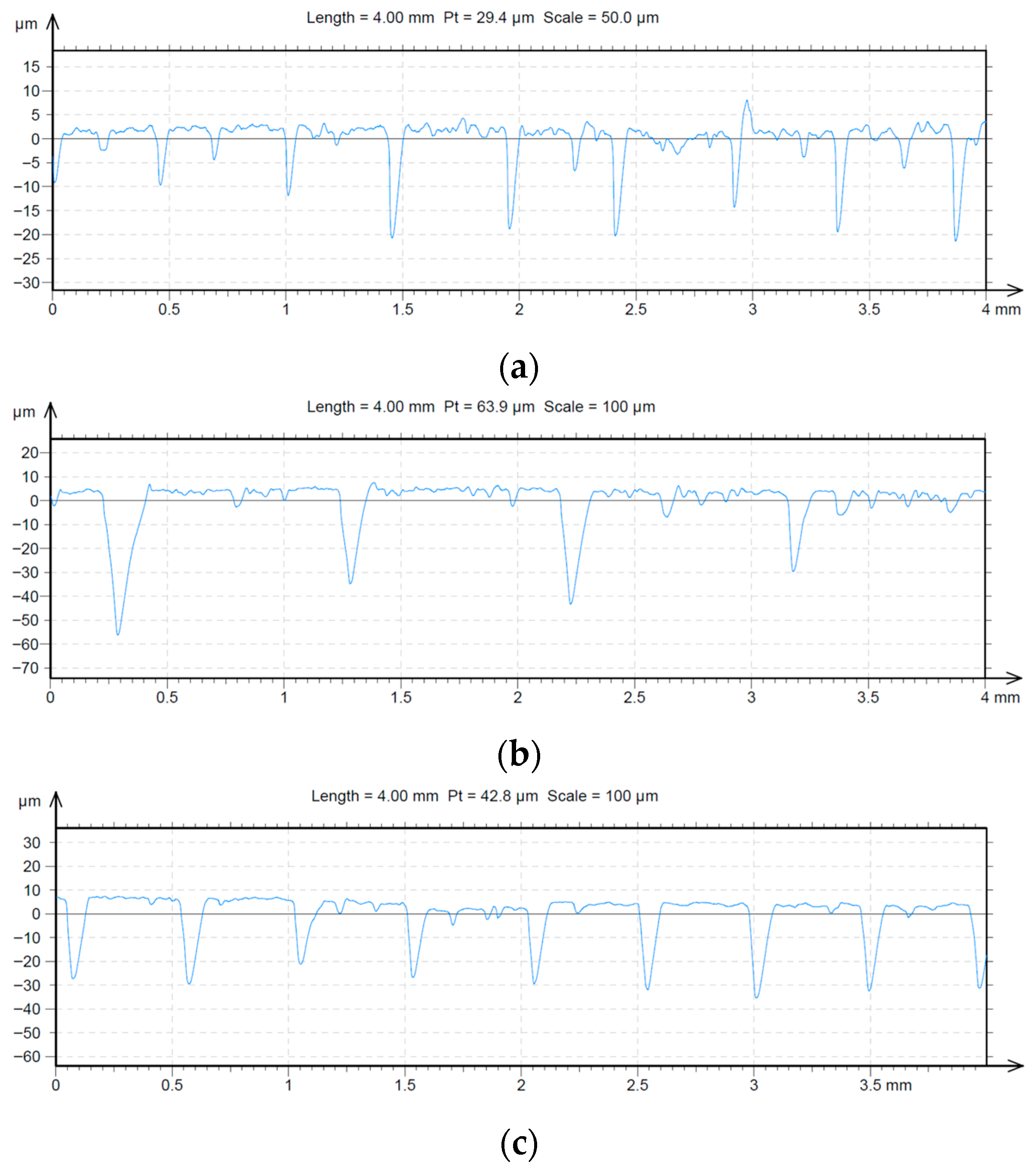

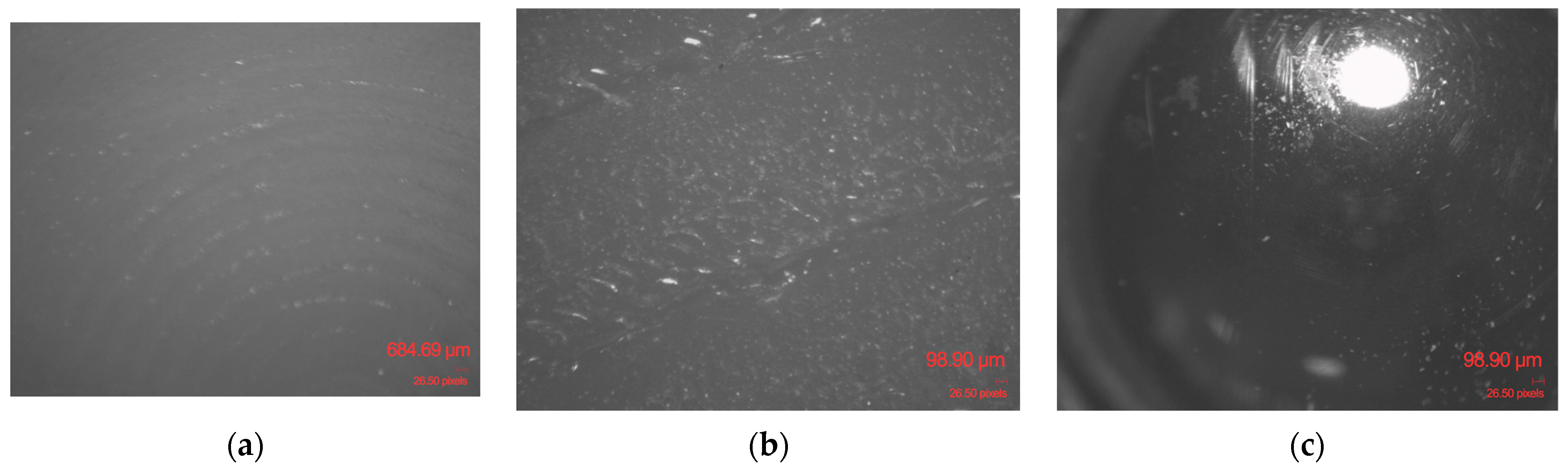

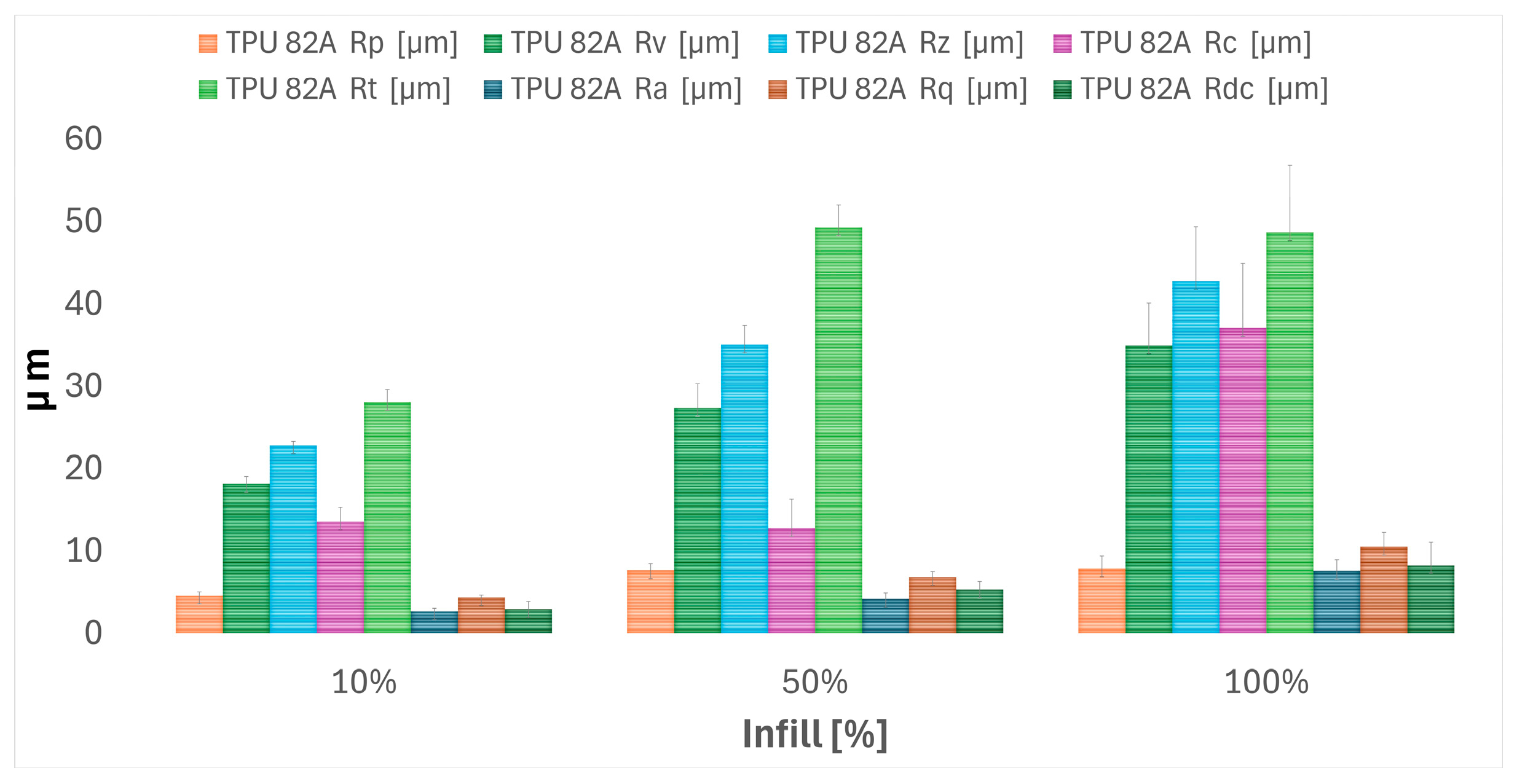

3.2. Surface Characterization

Comparison of Roughness and Contact Implications

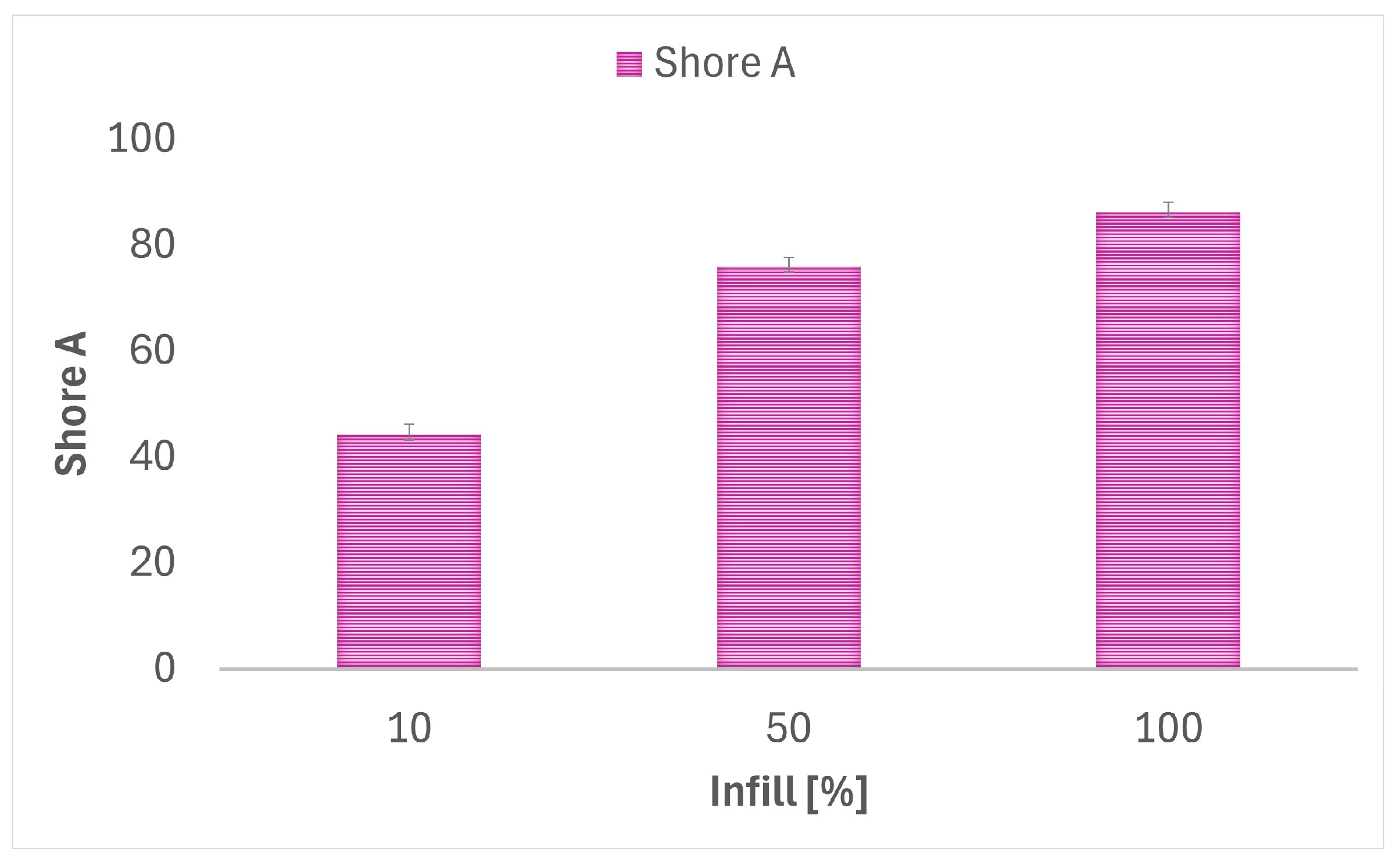

3.3. Hardness Evaluation

Interpretation in Context of Tribological Behavior

- The high stiffness of G100 minimized large-scale contact flattening, resulting in low, stable adhesion and low (0.456).

- The extreme compliance of G10 allowed the material to accommodate stress through large bulk elastic and viscoelastic deformation. While soft, porous structure limits the capacity for strong adhesion across the entire nominal contact zone, contributing to a moderate (0.504) and effective energy dissipation via damping.

- The G50 sample sits at an intermediate stiffness point (75.9 Shore A) where it is rigid enough to transmit the localized Hertzian pressure effectively but still compliant enough to fully plastically yield and flatten the surface asperities within the wear track. This optimal level of deformation maximized the true area of contact (real contact area saturation), leading directly to the observed peak adhesion and highest friction coefficient = 1.002).

3.4. Correlation and Mechanism Discussion

- Hardness → μ: The relationship between increasing bulk hardness (G10–G100) and μ was non-monotonic. Instead of consistently decreasing (as usually seen in softer polymers due to rising real contact area), the μ peaked at the intermediate density (G50).

- Roughness → μ: The nominally roughest surface (G100, high Ra) yielded the lowest friction, whereas the specimen that experienced the highest friction (G50) possessed intermediate roughness. This indicates that compliance (driven by infill structure), rather than initial measured Ra, is the decisive factor governing the effective real contact area under load for this hyper-elastic material.

Proposed Wear and Contact Mechanism

- G10 sample (energy damping dominance): The low infill provides an internal air-cushioned structure. Under the 231 MPa pressure, the material undergoes substantial elastic deformation well beneath the immediate contact surface. This internal rearrangement and viscoelastic damping effectively dissipate sliding energy, thus limiting the shear stress transfer required for high adhesion, resulting in a lower μ (∼0.504).

- G50 sample (adhesion maximization): The higher stiffness ensures that the contact stress is contained closer to the surface. The 50% infill structure likely prevents the deep bulk relaxation/deformation seen in G10 sample. Simultaneously, the intermediate compliance permits optimal flattening of the FFF surface topography, maximizing molecular adhesion between the TPU and the steel counterbody. This maximization of the adhesive component of friction yields the high μ peak (∼1.002).

- G100 sample (rigidity and reduced contact): The stiff, dense material minimizes both bulk deformation and local asperity flattening. The energy dissipation pathway relies more heavily on localized elastic rebound and limited adhesive shearing due to the smaller, more transient real contact area maintained under sliding conditions, leading to the lowest observed μ (∼0.465).

4. Implications for Sustainable Mobility

4.1. Promoting Eco-Efficient Design Through FFF-TPU

4.2. Functional Advantages and Replacement Potential

- Tailored tribological performance: This study confirmed that the tribological behavior of FFF-TPU 82A is intrinsically linked to its internal architecture. By modulating the gyroid infill density, the component’s functional surface characteristics can be precisely tuned:

- The G100 (100% infill) material yielded the lowest and most stable mean friction coefficient ( ≈ 0.465). This dense, rigid structure minimizes bulk deformation, relying on localized elastic rebound to restrict the real contact area. This low and stable friction makes it ideal for dry sliding elements where energy loss must be minimized, such as damping bushings or guiding components.

- The G50 (50% infill) material exhibited the highest friction ( ≈ 1.002) due to its intermediate stiffness, which provides an optimal balance of compliance and rigidity, promoting localized surface indentation and an increased real contact area during sliding. This capacity for stable, high-grip performance can be important for anti-slip components or components requiring high interfacial shear resistance.

- Exceptional wear resistance and surface adaptability: TPU is characterized by its superior wear resistance compared to many traditional rubber formulations (e.g., NR, BR, and SBR) [19]. The minimal volumetric material loss observed under dry sliding conditions for all infill densities, with friction primarily relating to viscoelastic energy dissipation rather than material removal, underscores the intrinsic durability of the FFF-printed TPU. This high durability contributes directly to reduced component maintenance and extended service life, a key element of sustainable mechanical systems [1]. Also, the capacity for local plastic deformation and viscoelastic energy damping exhibited by the FFF-TPU confirms its suitability for applications requiring significant impact energy absorption [22].

- Dimensional control and repeatability: Although FFF introduces characteristic surface roughness, the controlled printing process allows the creation of components with consistent material hardness and defined internal features, a level of geometric complexity and functional tailoring difficult to achieve economically with conventional molding techniques [1,15].

4.3. Practical Applications for Transportation

- Railway and heavy transport: TPU is already critical in the railway industry for enhancing impact resistance, particularly against flying ballast, when used as a coating on carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) laminates [20,21]. FFF-printed TPU 82A, leveraging its robust wear resistance and hardness consistency, is highly suitable for manufacturing damping bushings, vibration isolators, and suspension pads [17]. Additionally, TPU/waste rubber powder blends have been successfully evaluated as durable, waterproof seal layers for high-speed railway subgrades [32].

- Automotive and electric vehicles (EVs): The ability to create lightweight parts using gyroid infill structures directly supports the EV trend towards mass reduction for improved range and energy efficiency. FFF-TPU is proposed for manufacturing specialized flexible couplings and adaptive mounts in EVs. Composites including FFF-printed TPU components can replace conventional stiff metal–rubber bushings in suspension systems, allowing custom tuning of vehicle handling properties and trajectory control with minimal energy loss, as verified by preliminary simulations [17].

- Micromobility and anti-slip systems: In domains such as pedestrian infrastructure and micromobility, the FFF-TPU system can produce highly durable anti-slip components. The high friction coefficient achievable with the G50 infill ( ≈ 1.002) supports developing highly effective surface-textured composite outsoles for footwear or tire treads, surpassing the performance of leading composite materials on surfaces like ice and demonstrating superior abrasion resistance compared to injection-molded counterparts [34]. This approach facilitates the creation of reliable non-pneumatic tires, replacing traditional environmentally challenging rubber materials entirely [19].

4.4. Engineering Considerations for Sustainable Mobility Systems

5. Discussion and Future Research Directions

5.1. Critical Synthesis and Contribution to FFF Tribology Literature

5.1.1. Correlation Between Structural Compliance and Friction

5.1.2. Hardness and Surface Morphology Paradox

5.1.3. Novelty and Sustainability Implications

5.2. Identification of Current Research Gaps

- Limited understanding of combined geometric and tribological effects: There is an insufficient systemic understanding of the combined effects of complex infill geometries (e.g., gyroid, honeycomb, and lattice structures), FFF-inherent surface topography (anisotropy and spiral texture), and the resulting tribological mechanisms (adhesion vs. deformation vs. damping) in elastomeric FFF materials. Comprehensive models are needed to predict the transition point where bulk viscoelastic damping (G10) gives way to adhesion maximization (G50).

- Lack of long-term wear and fatigue data: The current study utilized a standardized test duration (300 m sliding distance) under stable conditions. For real-world mobility components (such as suspension bushings or seals in railway/automotive applications), data is critically lacking regarding the long-term wear rates, frictional stability, and fatigue performance under more realistic dynamic loads, variable speeds, and elevated temperature conditions, which influence the viscoelastic properties of TPU.

- Insufficient contact mechanics modeling for compliant structures: The application of the initial theoretical Hertzian contact pressure (231 MPa) dramatically changes once the compliant, internally structured material deforms. Current analytical models are inadequate for accurately describing the non-linear contact mechanics of compliant gyroid structures and predicting the true area of contact saturation observed at intermediate infill densities (G50).

5.3. Future Research Directions

- Future investigations on this topic should incorporate SEM and confocal microscopy analyses to enable high-resolution characterization of wear-track morphology. Such techniques are essential for identifying potential micro-cracking, material transfer, and third-body effects, as well as for verifying deformation features at the micro-scale. Integrating these advanced imaging methods would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms governing deformation-dominated wear in FFF-printed TPU components.

- Tribological testing under lubricated or mixed conditions: To increase the applicability of these findings to industrial mobility systems, future work should transition from dry sliding to tribological testing under lubricated or mixed friction regimes (e.g., oil or water-based lubricants). This will help in understanding how the gyroid architecture influences hydrodynamic stability and the formation of films transferred in wet environments.

- Finite element analysis (FEA) of infill deformation: Advanced FEA should be employed to simulate the complex stress distribution and large strain deformation within the gyroid lattice under high localized pressure. Such modeling would accurately predict the correlation between infill percentage, effective stiffness, and the onset of plastic yielding, allowing for optimized structural design that minimizes energy loss through friction.

- Exploring bio-based and recycled TPU filaments: Aligning with the principles of the circular economy, investigations must be initiated into the tribological performance and printability of bio-based or recycled TPU filaments. Assessing how sustainable feedstocks influence mechanical consistency, surface roughness, and friction coefficient is vital for validating FFF-TPU technology as a truly eco-efficient replacement for conventional materials.

- Dynamic mechanical and vibration testing: Given the TPU’s recognized function in vibration isolation and damping in railway and automotive applications, future studies should include Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) and vibration attenuation testing. Correlating the tailored infill density (and thus the viscoelastic properties) with effective damping ratios under relevant transport frequencies will be important for the adoption of FFF-TPU parts as lightweight structural components.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| BR | Butadiene Rubber |

| CFRP | Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer |

| DMA | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis |

| EV(s) | Electric Vehicle(s) |

| FDM® | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| NR | Natural Rubber |

| PBM | Polymeric Bearing Material |

| PEEK | Polyether Ether Ketone |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| SBR | Styrene-Butadiene Rubber |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| TPU | Thermoplastic Polyurethane |

Nomenclature

| µ | Friction coefficient |

| µmax | Maximum value of friction coefficient |

| Mean value of friction coefficient | |

| Ra | Arithmetic Mean Roughness |

| Rc | Average Mean Height of Profile Elements |

| Rdc | Reduced depth of the roughness profile |

| Rq | Root Mean Square Roughness |

| Rmr | Material Ratio |

| Rt | Total Height of Profile |

| Rp | Maximum Profile Peak Height |

| Rv | Maximum Profile Valley Depth |

| Rsk | Roughness Skewness |

| Rku | Roughness Kurtosis |

| Rz | Maximum height of profile |

References

- Dhakal, N. Development of 3D Printable Thermoplastic Polymer Composites for Tribological Applications. Doctoral Dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani, R.; Leon, R.R.; Nageswaren, R.; Rusho, M.A.; Shankar, K.V. Tribological performance enhancement in FDM and SLA additive manufacturing: Materials, mechanisms, surface engineering, and hybrid strategies—A holistic review. Lubricants 2025, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, R.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S.; Oladijo, O.P.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Advances in lightweight composite structures and manufacturing technologies: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Dua, S.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, S.K.; Senthilkumar, T. A comprehensive review on fillers and mechanical properties of 3D printed polymer composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, S.; Mishra, R.S. Building without melting: A short review of friction-based additive manufacturing techniques. Int. J. Addit. Subtractive Mater. Manuf. 2017, 1, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, W.J. Ecotribology: Environmentally acceptable tribological practices. Tribol. Int. 2006, 39, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Woydt, M.; Huq, N.; Rosenkranz, A. Tribology meets sustainability. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2021, 73, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birosz, M.T.; Ledenyák, D.; Andó, M. Effect of FDM infill patterns on mechanical properties. Polym. Test. 2022, 113, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenbiller, G.; Brooks, S.; King, O.; Constant, E.; Merckle, D.; Weems, A.C. 3D printing of green and renewable polymeric materials: Toward greener additive manufacturing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 3201–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Bagheri, Z.S. Investigating the impact of 3D printing process parameters on the mechanical and morphological properties of fiber–reinforced thermoplastic polyurethane composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 3432–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Espejo, C.; Morina, A.; Emami, N. Tribological performance of 3D printed neat and carbon fiber reinforced PEEK composites. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xu, C.; Khan, M. Tribological characterisation and modelling for the fused deposition modelling of polymeric structures under lubrication conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samykano, M.; Kumaresan, R.; Kananathan, J.; Kadirgama, K.; Pandey, A.K. An overview of fused filament fabrication technology and the advancement in PLA-biocomposites. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, G.; Botez, C.; Botez, S.C. Trends in The Use of Plastic Materials in 3D Printing Applications. Proc. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 19, 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.E.Y. Process-Related Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Semi-Crystalline Polymers in Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). Doctoral Dissertation, Rheinland-Pfälzische Technische Universität Kaiserslautern-Landau, Kaiserslautern, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Stiller, T.; Hausberger, A.; Pinter, G.; Grün, F.; Schwarz, T. Correlation of Tribological Behavior and Fatigue Properties of Filled and Unfilled TPUs. Lubricants 2019, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żur, A.; Żur, P.; Michalski, P.; Baier, A. Preliminary study on mechanical aspects of 3D-printed PLA-TPU composites. Materials 2022, 15, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chu, Z.; Guo, N.; Lv, X. Research on micro-mechanics modelling of TPU-modified asphalt mastic. Coatings 2022, 12, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, X.; Gao, L.; Liu, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R. Research of TPU materials for 3D printing aiming at non-pneumatic tires by FDM method. Polymers 2020, 12, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Rizzo, F.; Pucillo, G.; Pinto, F.; Meo, M. A thermoplastic polymer coating for improved impact resistance of railways CFRP laminates. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Composite Materials-18th, Athens, Greece, 24–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, F.; Cuomo, S.; Pinto, F.; Pucillo, G.; Meo, M. Thermoplastic polyurethane composites for railway applications: Experimental and numerical study of hybrid laminates with improved impact resistance. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2021, 34, 1009–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, G.; Wu, M.; Lin, L.; Liu, H.; Shi, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Du, K. Buffering Performance of 3d-Printed Tpu-Based Packaging: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Mech. Res. Commun. 2025, 148, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Kan, S.; Ji, J.; Shi, E. MDI-PTMG-based TPU modified asphalt: Preparation, rheological properties and molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel 2025, 379, 133007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, M.; Petrescu, M.G.; Ripeanu, R.G.; Laudacescu, E.; Tănase, M. Experimental Research on the Tribological Behavior of Plastic Materials with Friction Properties, with Applications to Manipulators in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Coatings 2025, 15, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norani, M.N.M.; Abdollah, M.F.B.; Abdullah, M.I.H.C.; Amiruddin, H.; Ramli, F.R.; Tamaldin, N. 3D printing parameters of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene polymer for friction and wear analysis using response surface methodology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2021, 235, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Wang, X.; Espejo, C.; Morina, A.; Emami, N. Impact of processing defects on microstructure, surface quality, and tribological performance in 3D printed polymers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 1252–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, M.C.; Popescu, D.; Stochioiu, C.; Baciu, F.; Hadar, A. Compressive behavior of thermoplastic polyurethane with an active agent foaming for 3D-printed customized comfort insoles. Polym. Test. 2024, 137, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, M.C.; Popescu, D.; Alexandru, T.G. Printability of thermoplastic polyurethane with low shore a hardness in the context of customized insoles production. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. D Mech. Eng. 2024, 86, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- FILAFLEX 82A Technical Data Sheet. Recreus Industries, S.L.: Elda, Spain. Available online: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1_JwtOY2UPBNhPmylzeXscT8cFyO9sB5T (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- FILAFLEX 82A Material Safety Data Sheet. Recreus Industries, S.L.: Elda, Spain. Available online: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1E3GJWUg-56zQUqFGNXeOi4nYkO90XcTi (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- ISO 4287:1997; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile Method—TERMS, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Cai, D.; Lou, L.; Xiao, F. A novel application of thermoplastic polyurethane/waste rubber powder blend for waterproof seal layer in high-speed railway. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 27, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, S.H.; Partanen, J.; Holmström, J. Additive manufacturing in the spare parts supply chain. Comput. Ind. 2014, 65, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Beschorner, K.; Bagheri, Z.S. Enhancing friction with additively manufactured surface–textured polymer composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indreș, A.I.; Constantinescu, D.M.; Baciu, F.; Mocian, O.A. Low velocity impact response of 3D printed sandwich panels with TPU core and PLA faces. UPB Sci. Bull. 2024, 86, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Designation | Infill [%] | μ 1 at Start | 2 ± SD 3 | μmax 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G100 | 100 | 0.472 | 0.465 ± 0.010 | 0.498 |

| G50 | 50 | 0.981 | 1.002 ± 0.023 | 1.057 |

| G10 | 10 | 0.614 | 0.504 ± 0.015 | 0.614 |

| Infill [%] | Rp Avg. 1 ± SD 2 [µm] | Rv Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rz Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rc Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rt Avg. ± SD [µm] | Ra Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rq Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rdc Avg. ± SD [µm] | Rsk Avg. ± SD | Rku Avg. ± SD | Rmr Avg. ± SD [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 4.61 ± 0.45 | 18.2 ± 0.88 | 22.8 ± 0.57 | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 28.1 ± 1.50 | 2.74 ± 0.34 | 4.39 ± 0.29 | 2.99 ± 0.90 | −2.38 ± 0.57 | 9.44 ± 2.31 | 0.62 ± 0.43 |

| 50 | 7.64 ± 0.88 | 27.4 ± 2.94 | 35.1 ± 2.28 | 12.8 ± 3.56 | 49.3 ± 2.70 | 4.22 ± 0.71 | 6.82 ± 0.66 | 5.35 ± 0.98 | −1.96 ± 0.29 | 9.18 ± 0.88 | 0.83 ± 0.82 |

| 100 | 7.84 ±1.61 | 34.97 ± 5.17 | 42.8 ± 6.59 | 37.1 ± 7.83 | 48.7 ± 8.16 | 7.6 ± 1.40 | 10.56 ± 1.73 | 8.31 ± 2.79 | −2.03 ± 0.17 | 6.19 ± 0.80 | 3.56 ± 1.23 |

| Sample Designation | Infill [%] | Mean Shore A Hardness ± SD 1 |

|---|---|---|

| G100 | 100 | 44.3 ± 1.94 |

| G50 | 50 | 75.9 ± 1.80 |

| G10 | 10 | 86.3 ± 1.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brăileanu, P.I.; Mocanu, M.-T.; Pascu, N.E. Tribological Assessment of FFF-Printed TPU Under Dry Sliding Conditions for Sustainable Mobility Components. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040184

Brăileanu PI, Mocanu M-T, Pascu NE. Tribological Assessment of FFF-Printed TPU Under Dry Sliding Conditions for Sustainable Mobility Components. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040184

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrăileanu, Patricia Isabela, Marius-Teodor Mocanu, and Nicoleta Elisabeta Pascu. 2025. "Tribological Assessment of FFF-Printed TPU Under Dry Sliding Conditions for Sustainable Mobility Components" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040184

APA StyleBrăileanu, P. I., Mocanu, M.-T., & Pascu, N. E. (2025). Tribological Assessment of FFF-Printed TPU Under Dry Sliding Conditions for Sustainable Mobility Components. Future Transportation, 5(4), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040184