Automated and Intelligent Inspection of Airport Pavements: A Systematic Review of Methods, Accuracy and Validation Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framework

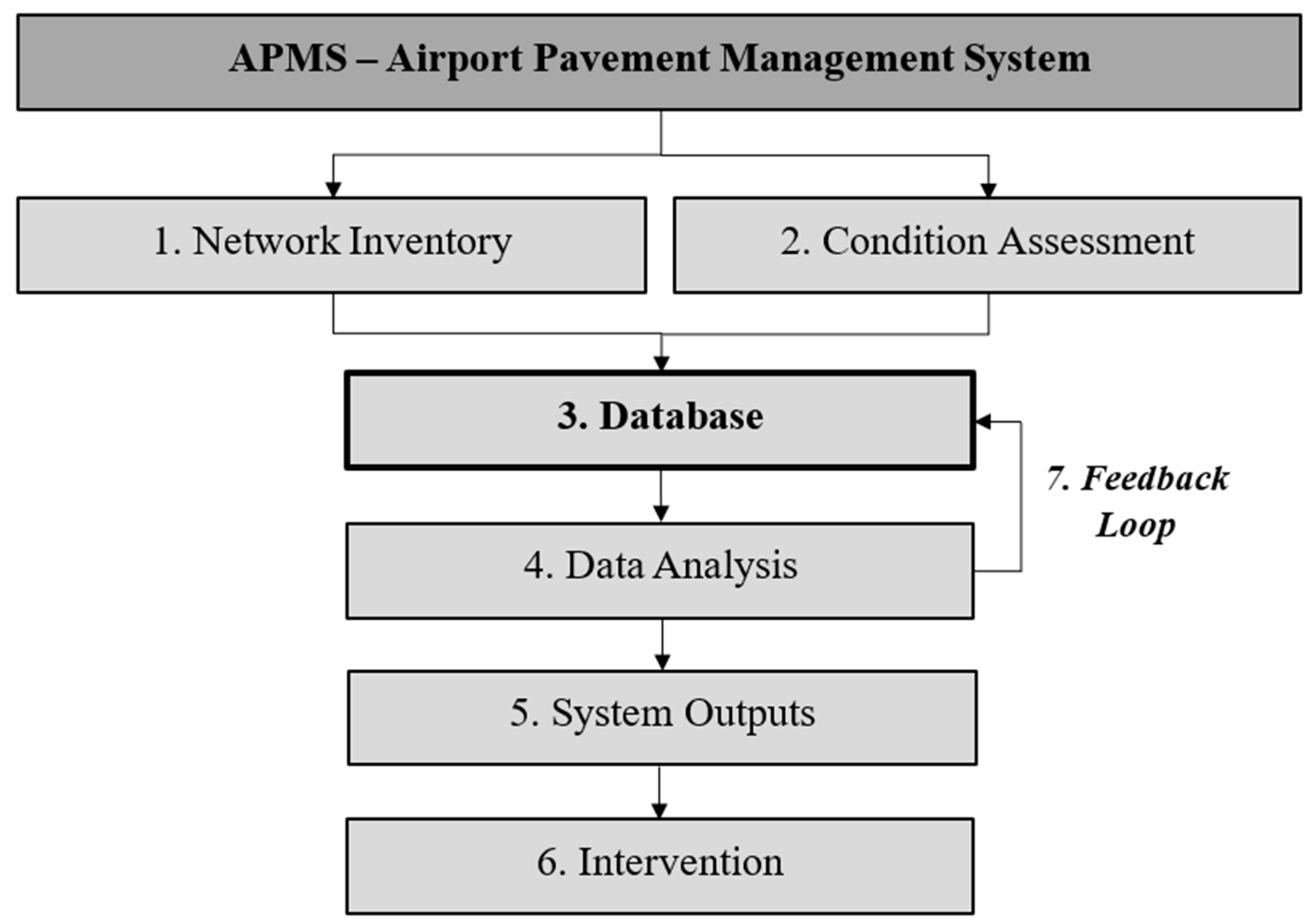

1.2. Airport Pavement Management System (APMS)

- Network Inventory: Systematic cataloging of the physical and functional components of airport infrastructure, including runways, taxiways, and apron areas. The inventory encompasses detailed information on materials, geometric characteristics, construction history, past maintenance activities, and traffic load intensity.

- Condition Assessment: Evaluation of the functional and structural condition of pavements using visual inspections, as well as destructive and non-destructive testing methods. Key performance indicators include the PCI and the ACN/PCN. This component also incorporates advanced technologies such as multifunctional vehicles, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) systems.

- Database: Centralized and structured storage of all data collected throughout the various stages of pavement management. Ensuring the integrity and continuous updating of the database is essential to perform consistent analyses and to support informed, data-driven decision-making.

- Data Analysis: Application of predictive models and simulations to estimate pavement distress progression, determine the optimal timing for interventions, and compare maintenance scenarios. This component also encompasses economic analyses focused on cost-effectiveness, return on investment, and overall sustainability.

- System Outputs: Generation of reports, charts, and thematic maps that prioritize maintenance and rehabilitation actions based on technical, functional, and financial criteria. These outputs provide objective and actionable support for informed decision-making by airport pavement managers.

- Intervention: Implementation of maintenance, rehabilitation, or reconstruction actions according to the priorities and technical recommendations generated by the APMS. This stage ensures that planned strategies are effectively executed in the field, bridging the gap between diagnostic assessment and practical application, and directly influencing pavement longevity and operational safety.

- Feedback Loop: Continuous refinement of predictive models through the integration of real-world data obtained from inspections and monitoring. This dynamic process enhances the accuracy of future forecasts and supports adaptive pavement management strategies.

1.3. Objectives

2. Airport Pavements: Types and Significance of Distress

- Structural capacity: ensures the integrity of the infrastructure under repeated and heavy loads generated by aircraft.

- Surface regularity: essential for stability during aircraft movement, preventing structural damage and supporting safe performance.

- Skid resistance: maintains adequate friction levels, particularly under adverse conditions such as wet pavements.

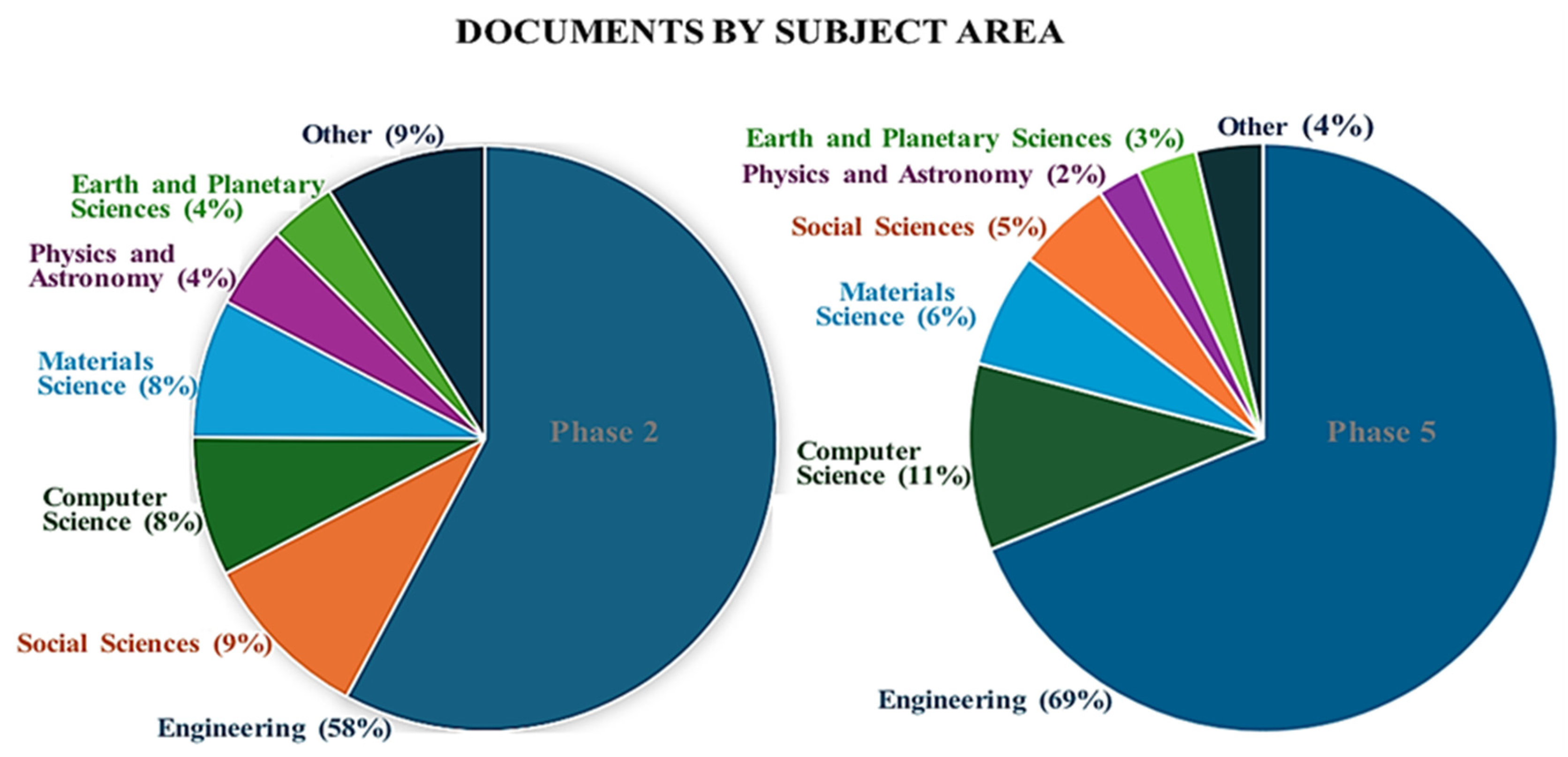

3. Search Method and a First Glance at Publications

4. Data Characterization, Trend Analysis, and Discussion

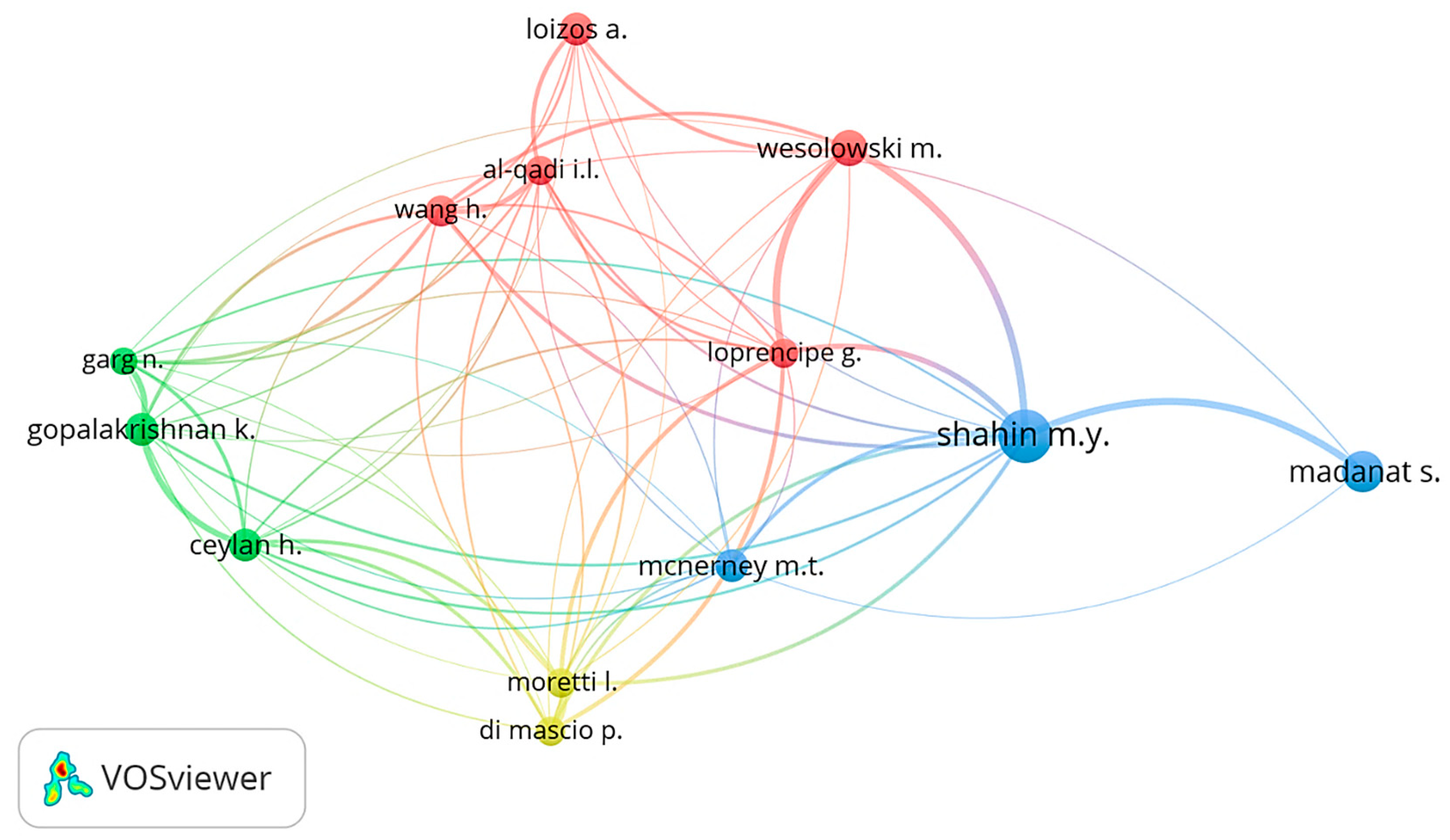

4.1. Document Characterization

- Red cluster: This cluster groups keywords such as “maintenance,” “airport pavement,” “airport runways,” “pavement management systems,” and “concrete pavements.” It reflects studies focused on infrastructure management, maintenance strategies, and operational aspects of airport pavements.

- Green cluster: This cluster includes terms such as “pavements,” “deep learning,” “inspection,” and “pavement inspections,” indicating research centered on automated inspection techniques, machine learning applications, and sensing technologies.

- Blue cluster: This cluster is organized around “pavement condition” and “pavement condition indices,” representing studies dedicated to evaluating pavement damage, performance indicators, and condition-based assessment methodologies.

- Additional cluster: The smaller connections forming the remaining cluster involve terms such as “airfield pavement,” showing how these concepts bridge condition assessment, airport pavement characteristics, and inspection methodologies.

4.2. Trend Analysis

| Ref.; Year; Country | Author | Title | Main Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| [7]; 2024; Indonesia | Wibowo, A.; Subagio, B.S.; Rahman, H.; Frazila, R.B. | Evaluation of the airport pavement condition index in the aircraft lateral wander area | Modeling PCI using lateral wander area |

| [54]; 2024; India | Kumar, P.; Gowda, S.; Gupta, A. | Implementation of airfield pavement management system in India | Developing an Airport Pavement Management System for India |

| [55]; 2024; United States | Frye, J.J. | Climate change impacts on Arctic airfields | Assessing climate impact on airfield pavement performance in Arctic regions |

| [44]; 2024; United States | Sourav, M.A.A.; Ceylan, H.; Brooks, C.; Dobson, R.; Kim, S.; Peshkin, D.; Brynick, M. | Use of small unmanned aircraft systems in airfield pavement inspection: implementation and potential | Evaluating UAV-based imagery for automated pavement distress inspection and PCI calculation |

| [45]; 2024; United States | Sourav, M.A.A; Ceylan, H.; S. Kim, S.; Brynick, M. | Integration of small unmanned aircraft systems and deep learning for efficient airfield pavement crack detection and assessment | Detecting airfield pavement distresses automatically using YOLOv8 |

| [46]; 2024; United States | McNerney, M.T.; Bishop, G.; Saur, V. | Using AI and change detection in geospatial UAS airfield pavement inspection for pavement management | Identifying pavement distresses and performing change detection using AI-enabled UAV imagery |

| [47]; 2023; United States | McNerney, M.T.; Bishop, G.; Saur, V. | Experiences gained and benefits from using uncrewed aerial systems to calculate pavement condition index at over 80 airports in the United States | Implementing full-scale UAV-based inspection for airport pavement PCI evaluation |

| [28]; 2023; Spain | Alonso, P.; Gordoa, J.A.I.; Ortega, J.D.; García, S.; Iriarte, F.J.; Nieto, M. | Automatic UAV-based airport pavement inspection using mixed real and virtual scenarios | Segmenting pavement defects using UAV imagery and synthetic datasets through deep learning |

| [56]; 2023; Czech Republic | Maslan, J.; Cicmanec, L. | A system for the automatic detection and evaluation of the runway surface cracks obtained by unmanned aerial vehicle imagery using deep convolutional neural networks | Detecting and measuring transverse cracks on concrete runways using UAV and YOLOv2 |

| [57]; 2023; Iraq | Kareem, N.M.; Ibraheem, A.T. | Developing a frame design for airport pavements maintenance management system | Developing an expert system for airport pavement maintenance decision support |

| [32]; 2022; United States | Pietersen, R.A.; Beauregard, M.S.; Einstein, H.H. | Automated method for airfield pavement condition index evaluations | Assessing PCI through partially automated UAV imagery and CNN modeling |

| [58]; 2022; Chile | Cereceda, D.; Medel-Vera, C.; Ortiz, M.; Tramon, J. | Roughness and condition prediction models for airfield pavements using digital image processing | Estimating IRI and PCI using automated digital image processing |

| [59]; 2022; China | Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. | Multi-task learning for pavement disease segmentation using wavelet transform | Segmenting pavement diseases with a multi-task deep-learning network |

| [60]; 2022; China | Li, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, P. | Research on airport pavement condition information system | Developing an integrated airport pavement condition information system with intelligent distress management |

| [61]; 2021; Czech Republic | Maslan, J.; Cicmanec, L. | Setting the flight parameters of an unmanned aircraft for distress detection on the concrete runway | Optimizing UAV flight parameters for pavement crack detection |

| [62]; 2021; China | Liu, Z.; Gu, X.; Dong, Q.; Tu, S.; Li, S. | 3D visualization of airport pavement quality based on BIM and WebGL integration | Integrating BIM and WebGL for 3D visualization of airport pavement condition |

| [63]; 2021; United States | Hafiz, A.; Celaya, M.; Jha, V.; Frabizzio, M. | Semi-automated method to determine pavement condition index on airfields | Calculating PCI semi-automatically using 3D laser scanning and Distress Inspector software developed by the authors. |

| [64]; 2020; Portugal | Santos, B.; Feitosa, I.; Almeida, P.G. | Validation of an indirect data collection method to assess airport pavement condition | Validating a low-cost in-vehicle pavement distress inspection system for APMS applications |

| [65]; 2020; India | Vyas, V.; Singh, A.P.; Srivastava, A. | Quantification of airfield pavement condition using soft-computing technique | Prioritizing airfield pavement maintenance using fuzzy AHP methodology |

| [49]; 2020; Poland | Iwanowski, P.; Wesołowski, M. | Evaluation of the cement concrete airfield pavement’s technical condition based on the APCI | Developing the APCI integrating structural and surface parameters |

| [16]; 2020; Poland | Wesołowski, M.; Iwanowski, P. | Evaluation of asphalt concrete airport pavement conditions based on the Airfield Pavement Condition Index (APCI) in scope of flight safety | Applying a comprehensive APCI-based method for technical pavement assessment |

| [9]; 2019; Portugal | Carvalho, A.F.C.; Picado Santos, L.G.D. | Maintenance of airport pavements: the use of visual inspection and IRI in the definition of degradation trends | Analyzing PCI and IRI evolution trends for pavement condition assessment |

| [66]; 2019; Cape Verde and Portugal | Lima, D.; Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G. | Methodology to assess airport pavement condition using GPS, laser, video image and GIS | Validating a vehicle-mounted inspection method for PCI evaluation in Cape Verde |

| [50]; 2019; Italy | Di Mascio, P.; Moretti, L. | Implementation of a pavement management system for maintenance and rehabilitation of airport surfaces | Applying an integrated APMS for maintenance prioritization in Italian airport pavements |

| [67]; 2019; Egypt | Fathalla, S.; El-Desouky, A. | Evaluation of pavement surface conditions for Luxor International Airport | Evaluating pavement surface condition at Luxor International Airport using PCI and Micro PAVER |

| [51]; 2018; Poland | Zieja, M.; Blacha, K.; Wesołowski, M. | Assessment method of the deterioration degree of asphalt concrete airport pavements | Estimating airport pavement deterioration using a multicriteria weighted assessment method |

| [68]; 2017; United States and Chile | Sahagun, L.K.; Karakouzian, M.; Paz, A.; Fuente-Mella, H.D.L. | An investigation of geography and climate induced distresses patterns on airfield pavements at US Air Force installations | Analyzing climate-induced distress patterns on U.S. Air Force airfield pavements |

| [69]; 2016; United States | Dabbiru, L.; Wei, P.; Harsh, A.; White, J.; Ball, J.E.; Aanstoos, J.; Donohoe, P.; Doyle, J.; Jackson, S.; Newman, J. | Runway assessment via remote sensing | Assessing runway surface roughness using microwave remote-sensing techniques |

| [70]; 2016; United States | Parsons, T.A.; Pullen, B.A. | Relationship between climate type and observed pavement distresses | Correlating climate regions with pavement distress types on USAF airfields |

| [71]; 2015; China | Ling, J.-M.; Du, Z.-M.; Yuan, J.; Tang, L. | Airfield pavement maintenance and rehabilitation management: Case study of Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport | Developing a decision-tree approach for maintenance and rehabilitation planning at Shanghai International Airport |

| [72]; 2013; United States | Graves, S.W. | Electro-optical sensor evaluation of airfield pavement | Integrating electro-optical FOD detection systems for pavement condition monitoring |

| [73]; 2004; Canada and Singapore | Huang, B; Fwa, T.; Chan, W.T. | Pavement-distress data collection system based on mobile geographic information system | Designing a mobile GIS-based data-collection system for airport pavement distress surveys |

| [74]; 2003; Singapore | Fwa, T.F.; Liu, S.B.; Teng, K.J. | Airport pavement condition rating and maintenance-needs assessment using fuzzy logic | Developing a fuzzy logic-based system for pavement condition rating and maintenance needs |

| [75]; 1992; United States | Rada, G.R.; Schwartz, C. W.; Witczak, M.W.; Rabinow, S. D. | Integrated pavement management system for Kennedy International Airport | Implementing an Integrated Airport Pavement Management System at John F. Kennedy Airport |

| [76]; 1992; United States | Hall, J.W.; Grau, R.W.; Grogan, W.P.; Hachiya, Y. | Performance indications from army airfield pavement management program | Evaluating pavement condition and maintenance alternatives for U.S. Army airfields |

| [77]; 1992; United States | Eckrose, R.A.; Reynolds, W.G. | Implementation of a pavement management system for Indiana airports—a case history | Developing a statewide Airport Pavement Management System for Indiana airports |

| [78]; 1991; United States | Beaucham, E.B. | Evaluating army airfields | Assessing pavement strength using nondestructive testing (FWD) and PCI evaluation |

| [53]; 1982; United States | Shahin, M.Y.; Kohn, S.D. | Airfield pavement performance prediction and determination of rehabilitation needs | Predicting airfield pavement performance and rehabilitation needs |

| Ref.; Pavement Type | Research Maturity/ Technical Focus | Inspection Method | Inspection Tools | Type of Pavement Distress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7]; AC | Initial: data processing & analysis; change detection; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Image recording, ruler | Cracking (alligator, LT, block, slippage); rutting; raveling; weathering; patching; bleeding; depression |

| [54]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; change detection; pavement management | Multifunctional vehicle | Automated Road Survey System (ARSS), Pavement Surface Imaging System (PSIS) | Cracking; raveling; weathering; corrugation; rutting; depression |

| [55]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; predictive modeling | Traditional on-foot | NDT/Geotechnical: rotary drilling rigs, automatic weather stations | Permafrost settlement; thermal and frost-related cracking; rutting; drainage distress; joint and edge deterioration |

| [44]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and UAV-based | UAV: DJI Mavic 2 Pro (RGB, 20 MP), 2 x M2EA (Quad Bayer RGB, 48 MP), FLIR thermal sensor, Bergen Hexacopter, Tarot X6 (Nikon D850, 45.7 MP), GPS tablets | Cracking (alligator, corner, block, LTD, D-cracking, shrinkage); joint damage; patching; spalling; popouts; scaling; shattered slabs; ASR; settlement/faulting; raveling; weathering; swelling; depression; shoving |

| [45]; AC and PCC | Advanced: database; data processing; change detection; pavement management | UAV-based | DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Advanced (RGB, 48 MP/Thermal sensor) | Cracking (corner, LTD); shattered slabs |

| [46]; AC and PCC | Advanced: database; data processing & analysis; change detection; pavement management | UAV-based | High-resolution geospatial sensors | Spalling (joint/corner); joint seal damage; depression; raveling; weathering; swell; ASR |

| [47]; AC and PCC | Advanced: database; data processing & analysis; change detection | UAV-based | Silent Falcon platform | Cracking (block, joint, LT); rutting; raveling |

| [28]; PCC (virtual) | Initial: data processing & analysis | UAV-based virtual | AirSim simulated UAV (physical hardware: NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier) | Cracking; other minor surface distress |

| [56]; PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management; validation study | UAV-based | DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual (RGB/Thermal), DJI Pilot v2.5.1.10 | Transverse cracking |

| [57]; AC and PCC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management; validation study | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking (block, corner, LT, D-cracking; map); scaling; ASR; spalling |

| [32]; AC | Advanced: database; data processing & analysis; change detection; validation study; pavement management | UAV-based | Custom MAV Hexcopter (FLIR Duo Pro R camera, Mission Planner 1.3.74 software) | LT cracking; patching; rutting; raveling |

| [58]; PCC | Advanced: database; data processing & analysis; validation study; pavement management. | Multifunctional vehicle | Van-type vehicle, LCMS, HD camera | Cracking (block, LT); roughness; scaling; spalling |

| [59]; PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; change detection; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Grayscale camera | Cracking, patching; repair marks |

| [60]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: Data processing & analysis; pavement management | Multifunctional vehicle | DAQ tools (handheld/vehicle-based), control software (DAQ), lighting system, GPS | Not specified |

| [61]; AC and PCC | Initial: data processing; validation study | UAV-based | DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual (RGB/Thermal), DJI Pilot application (version V01.00.0860) | Cracking (unspecified) |

| [62]; PCC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Patching; joint damage; subsidence/faulting; punchout |

| [63]; PCC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management; validation study | Multifunctional vehicle | 3D LCMS, HD cameras, LiDAR (LDTM), AID-ITV (Integrated Testing Vehicle) | Not specified |

| [64]; AC | Intermediate: database; data processing & analysis; change detection; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and multifunctional vehicle | Measuring wheel, chalk/ruler, metallic structure, pickup vehicle, 20 mW laser beams, Garmin Elite video camera, GPS setup (Trimble 4000SSi, GeoXT), laptop | Cracking (alligator, LT); patching; weathering; raveling; depression |

| [65]; AC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and NDT (HWD; GPR) | NDT: Dynatest HWD 8081, GPR (400 MHz antenna), ELMOD 6 software | Cracking (alligator, fatigue, block); raveling; patching; depression; rutting; corrugation; potholes |

| [49]; PCC | Initial: database; data analysis | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking (slotted, edge, corner); spalling; joint damage; scaling; deep cavities |

| [16]; AC | Initial: database; data analysis | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking, chipping; rutting; fracturing; raveling |

| [9]; AC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and multifunctional vehicle (IRI) | Survey vehicle (tri-laser sensor system—one central, two lateral sensors) | Cracking (alligator, block, LT); patching; raveling; rutting; corrugation; depression |

| [66]; AC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and multifunctional vehicle | Measuring wheel, chalk/ruler, metallic structure, pickup vehicle, 2 × 20 mW laser generators, Garmin Elite video camera, GPS setup (2 Trimble 4000SSi), laptop | Cracking (alligator, LT); patching; rutting; raveling; depression; corrugation |

| [50]; AC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and multifunctional vehicle | Multifunctional vehicle (FWD; HWD, laser texture scanner, high-resolution cameras, crack scale, laser profilers) | Cracking (alligator, block, LT) |

| [67]; AC and PCC | Initial: database; data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking (block, LTD, D-cracking, corner, shrinkage); depression; raveling; weathering; patching; oil spillage; polished aggregate; joint damage; scaling; spalling; ASR; popouts; bleeding |

| [51]; AC (implicit) | Initial: database; data analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Distress and repair (types not specified) |

| [68]; AC and PCC | Initial: data analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking (alligator, corner, D-cracking, shrinkage, linear); raveling; joint damage; patching; scaling; shattered slab; spalling |

| [69]; AC | Initial: data processing & analysis; validation study | Remote sensing (SAR satellite + LiDAR) | SAR (TerraSAR-X, TanDEM-X, X-band), LiDAR (Leica ALS70), GPS (Leica 500 dual-frequency), DEM (Grafnet/Leica Office) | Not specified |

| [70]; AC and PCC | Initial: data analysis; validation study | Traditional on-foot | Not specified | Cracking (alligator, block, corner, D-cracking, joint reflection); bleeding; raveling; popouts; scaling; rutting; swelling; ASR |

| [71]; PCC | Initial: data analysis; pavement management | Not specified | Not specified | Cracking (transverse, corner); joint damage; spalling; popouts; scaling; patching |

| [72]; AC and PCC | Initial: database; data processing; validation study; pavement management | Traditional on-foot and electro-optical sensor | iFerret sensor system, standard camera, steel strips (simulated cracks), ImageJ software | LT cracking; joint spalling; patching; shattered slab; faulting |

| [73]; AC | Initial: database; data processing; pavement management | Traditional on-foot with mobile GIS (GPS/PDA-based) | PDA: DGPS receiver (Topcon Turbo G2), Spectec SD digital camera, mobile GIS (ArcPad), Pocket PC (Compaq iPAQ H3700) | Cracking; raveling |

| [74]; AC | Intermediate: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler and standardized forms | Cracking; potholes |

| [75]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler and standardized forms | Cracking; rutting; spalling |

| [76]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler, standardized forms, FWD/NDT | Cracking; rutting |

| [77]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler, standardized forms, APMS software | Cracking; raveling; rutting; spalling |

| [78]; AC and PCC | Initial: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler, standardized forms, NDT | Not specified |

| [53]; AC and PCC | Intermediate: data processing & analysis; pavement management | Traditional on-foot | Ruler and standardized forms | Cracking (alligator, LT, block, joint reflection, edge); raveling; bleeding; patching; weathering |

| Ref. | Data Processing Technique(s) | Accuracy | Statistical Analysis/ Validation | Big Data/ Volume | Quality Index | 3D Modelling | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Not specified | - | Regression; standard deviation analysis; and scenario comparison | No: not specified | PCI CDF | - | - |

| [54] | GIS-based and PAVER | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [55] | PAVER; statistical modeling; climatic and geotechnical data analysis | - | Correlation analysis between pavement distress and environmental factors; predictive modeling for deterioration trends | Yes: data from 4 airfields; climatic/ geotechnical data (no quantify) | PCI | - | - |

| [44] | Photogrammetry (Agisoft Metashape); DEM and hillshade generation; GIS-based spatial alignment; PCI calculation (FAA PAVEAIR) | Pearson correlation R = 0.79–0.90 | PCI comparison (UAV-based vs. FOG) and correlation analysis | No: not specified | PCI | DEM; hillshade (3D surface view) | - |

| [45] | Image annotation (LabelImg); data augmentation; YOLOv8 (nano to large); Roboflow platform; Python-based image splitting | mAP50: 0.65–0.69; precision up to 0.74; recall up to 0.72 | - | No: 5.273 images; high-resolution (8000 × 6000 px); real-time processing possible (nano/ small models) | - | - | DL with YOLOv8 |

| [46] | AI (DL) and change detection software | - | Comparison with traditional methods (not specified) | Yes: data from over 100 airports (no quantity) | PCI | - | DL (not specified) |

| [47] | Orthorectification of images and 3D modelling | - | Correlation analysis between UAV-derived PCI and manual inspections | Yes: data from over 80 airports (no quantity) | PCI | Orthoimage; 3D modelling | - |

| [28] | DNN-based image segmentation (EfficientNet + Feature Pyramid Network—FPN) | F1-score; IoU; ODS; and OIS | Performance comparison on synthetic and real datasets | Yes: multiple public datasets (no quantity) | - | Unreal Engine 5 (virtual 3D simulation); DAQ | CNN |

| [56] | Orthoimage generation (Agisoft); image annotation/ labeling (Matlab Image Labeler); DL segmentation/ detection (Matlab DL Toolbox). | Detection performance evaluated using Precision, Recall, F1-score, AP, IoU, LAMR | - | No: 3.279 images | - | Orthomosaic (Agisoft Metashape); DEM; sparce/dense point cloud | YOLOv2; ResNet-50 (MATLAB) |

| [57] | RPC software developed by the authors; comparison with MicroPaver 5.3.2; and EPCM | R2 | Regression model (PCI vs. IRI) and coefficient of determination (R2) | No: not specified | PCI; PSI/PSR-reg. (indirect data) | - | - |

| [32] | Orthoimage generation (Agisoft); data augmentation; semantic segmentation (DeepLabV3+); IoU evaluation | ≤94% GA and 0.72 IoU in distress detection | - | No: not specified | PCI | Orthoimage mapping; 3D-printed mount (SolidWorks CAD) | DeepLabV3 (CNN); ResNet-18/-50; Xception; Inception-ResNet-V2 (MATLAB) |

| [58] | LCMS data processing with MATLAB | R2 | Non-linear regression analysis (Levenberg- Marquardt); R2 validation | Yes: 24.825 images | PCI; IRI | LCMS–3D surface profiling | - |

| [59] | DWT; semantic segmentation; channel attention mechanism; and feature fusion branch | CPA: 82.67%; IoU: 49.17% (best:69.96% for light, worst:11.59% for crack) | Model comparison: U-Net, DeepLabv3, DeepLabv3+, BiSeNet, BiSeNetv2; and ablation study | No: 3.467 images | - | - | CNNs: ResNet; MTSSN-WT; PyTorch; SGD |

| [60] | DL; GIS; and image processing software | - | - | Not specified | PCI; SCI | - | DL (not specified) |

| [61] | Digital photogrammetry (Agisoft); sparse/dense point cloud reconstruction; ortho-mosaic/DEM generation; MATLAB | MSE; RMSE; R2; and adjusted R2 | Regression; theoretical vs. actual spatial resolution (GRD & GSD) validation | No: 3.361 images | - | Point cloud reconstruction; surface mesh; DEM | - |

| [62] | JSON-OBJ conversion; PCI view (color/height); WebGL and Three.js. | Not specified | - | Not specified | PCI | BIM (Autodesk Revit); parametric 3D modelling | - |

| [63] | Image stitching; GPS alignment correction; point cloud analysis; DI; PCI; export to Paver/XML and GIS/KML | Not specified | - | Yes: 50 units—LCMS and point cloud (moderate volume) | PCI | 3D laser scan; point cloud data | - |

| [64] | GNSS-based image processing; GIS-based visualization; distress digitization; and PCI calculation | Strong correlation with on-foot inspection (R2 = 0.8993) | Normal tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, Shapiro–Wilk), paired t-test; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; PCI; distress metric comparison (on-foot vs. vehicle) | No: 2.000 images | PCI | - | - |

| [65] | Back calculation (HWD/ELMOD 6); GPR thickness analysis; deflection bowl analysis; PCI calculation; and fuzzy AHP for section prioritization | - | - | No: 22.000 data points (HWD; GRP; on-foot inspection) | ACN/PCN; PCI; layer moduli-BC | - | - |

| [49] | - | - | - | No: not specified | PCI; APCI | - | - |

| [16] | - | - | - | No: not specified | PCI; APCI | - | - |

| [9] | Regression; statistical significance testing; and residual analysis | High for PCI models (adjusted R2 ≤ 88%); low for IRI models (data/fit issues) | Regression; hypothesis testing (t-test); residual analysis; model comparison; data interpolation | No: not specified | PCI; IRI | - | - |

| [66] | GNSS-based image processing; GIS-based visualization; distress digitization; and PCI calculation | PCI variation ≤ 5 points between methods | PCI comparison in-vehicle vs. on-foot inspections | No: 2.000 images | PCI | - | - |

| [50] | Back-calculation (HWD); laser-based ETD/PCI; chromatic mapping; profilograph analysis; MFV-based IRI, RUT, and skid resistance processing | Not specified | Based on reference thresholds | No: not specified | PCI; IRI; RUT; EDT; ACN/PCN | - | - |

| [67] | MicroPAVER 5.2 software | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [51] | Statistical analysis with distress indices | Not specified | Histograms; regression; probability analysis (distress indices/condition classification) | No: not specified | Degree Index (D) | - | - |

| [68] | Statistical analysis and geostatistical modeling (kriging via ArcMap) | - | Weighted averaging; normalization; regression; hypothesis testing (t-/Mann–Whitney tests); comparison between zones; kriging; spatial trend analysis | Yes: 50.000+ distress records from 77 USAF installations | - | - | - |

| [69] | LiDAR-based DEM; TRI calculation; linear and polynomial regression | R2 ≤ 0.46 (radar vs. TRI) | Regression; R2 as fit metric; correlation analysis (radar backscatter vs. TRI; validated with ground-truth LiDAR) | No: high- resolution data with localized scope | TRI | DEM from LiDAR-based | - |

| [70] | PAVER database and statistical analysis | - | ANOVA; main effect analysis; interaction effect analysis | Yes: 17.565 extrapolated records from >435 k distresses data points | - | - | - |

| [71] | Not specified | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [72] | Image processing: background subtraction, image subtraction, feature measurement (RGB error, pixel sizing, contrast plots) | - | PCI manual comparison; image inspection; and crack simulation with physical targets | No: 39 slabs analyzed; simulated images (iFerret) | PCI | - | - |

| [73] | Real-time GPS conversion; chainage mapping; spatial indexing; GIS query | Location accuracy ≈ 0.5 m (DGPS) | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [74] | Fuzzy logic inference system (fuzzifier, rule engine, defuzzifier); decision rules | - | No; only expert review | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [75] | Database-driven PMS with forecasting and analysis tools; GIS integration | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [76] | PCI vs. age trends; core evaluation; decision criteria | - | No; qualitative comparisons (PCI vs. age trends; core–design; method-based decisions) | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [77] | PCI-based condition scoring; capital improvement program via software; forecasting | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [78] | Not specified | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

| [53] | Empirical modeling with PCI methodology (precursor to PAVER) | - | - | No: not specified | PCI | - | - |

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. Airport Pavement Inspection Methods

On-Foot Visual Inspection

Multifunctional Vehicle Inspection

UAV-Based Inspection

4.3.2. Functional and Structural Indexes

4.3.3. Emerging Technologies in Pavement Inspection

Data Processing

Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

| Category | Size Criterion | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| Small data | ≤1.000 records/images | Pilot studies, tests, spot inspections |

| Moderate data | 1.000 to 10.000 records/images | Local or single-task datasets |

| Large data | 10.000 to 100.000 records | Regional studies, multivariate models |

| Big Data | >100.000 records or featuring the 5Vs 1 | Integrated sources, sensor networks, real-time data, high variety |

4.3.4. Results Achieved in Terms of Cost, Time, Accuracy, and Complexity

| Technology/Platform | On-Foot Visual | Multifunctional Vehicle | UAV (RGB) | UAV (LiDAR) | AI/DL Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Sensors | Digital camera, ruler, GPS | LCMS + RGB + DMI + GNSS | RGB 20–100 MP | LiDAR + RGB + GNSS + SAR | CNN/YOLO/DeepLab/FPN pipelines |

| Typical Ground Resolution (mm/pixel) | 0.5–1.0 [9,16,50,59,64,66,77] | Transverse laser resolution ≈ 1 mm; depth ≈ 0.5 mm; profile spacing ≈ 150 mm [58,63] | 1.0–3.0 (consolidated) 0.7–7.3 [44]; 1.5 [46]; 6.4–8.6 [56]; High-res RGB [28,45] | 5.0–10.0 mm UAV LiDAR (point spacing); (SAR: ~500 mm/pixel; airborne Lidar: ~180 mm) [69] | Varies according to dataset [28,32,56,59] |

| Average Inspection Speed (km/h) | 0.25–0.35 [9,16] | 10.0–15.0 [58] | 3.0–6.0 [28,44] | Minor fix 3.0–5.0 km/h (consistent with UAV LiDAR surveys) [69] | Depending on image acquisition platform |

| Crack Detection (F1/IoU) | – | – | F1 = 0.81–0.90 [28,32,56]; IoU = 0.70–0.75 [28,32] | – | F1 = 0.81 [56]; IoU = 0.72 [32]; Acc > 90% [28,45] |

| Correlation with PCI (R2) | – | R2 ≈ 0.89 [63] | R2 ≈ 0.79–0.90 [44] | – | – |

| Implementation Costs (10 km) | Low | High | Medium | High | Medium-High |

| Operational Cost (10 km) | High | Medium | Low | Medium | Low |

| Field Time (1 km) | 6–10 h [9,16] | 8–12 min [58,63] | 15–25 min [28,44,45,46,56] | 20–30 min [69] | – |

| Notes/Key Limitations | Subjectivity; operational disruption | High accuracy, high upfront cost | Limited battery; regulatory constraints | High cost; superior 3D data | Depending on dataset & validation protocol |

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Methodological standardization, through the development of integrated protocols covering data collection, processing, and validation, particularly for AI-based methods, where heterogeneous practices hinder result comparability.

- Gradual and hybrid adoption of technologies, combining well-established traditional methods with low-cost automated solutions. This strategy enables scalable transitions, allowing airports with technical or budgetary constraints to progressively adopt innovations.

- Strengthening statistical validation, through robust inferential testing and cross-validation, to ensure reliable, generalizable, and replicable results.

- Integration of Big Data sources to enhance AI applications, enable more accurate predictive modeling, and support better-informed decisions.

- Customization of inspection solutions, tailored to local operational and budgetary contexts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orabi, J.; Shatila, W. Life cycle assessment and life cycle cost analysis for airfield pavement: A review article. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šabić, M.; Šimić, E.; Damir, D. Airport Pavement Maintenance and Repair. In New Technologies, Development and Application VI; Karabegovic, I., Kovačević, A., Mandzuka, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 707, pp. 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, I. Validation of an Indirect Auscultation Method for Assessing the Quality of Airport Pavements. Master’s Thesis, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 2020. Available online: https://ubibliorum.ubi.pt/entities/publication/e62c3c86-8df3-465d-8ba8-ba7d72980334 (accessed on 23 April 2025). (In Portuguese).

- Fernandes, C.I. Airport Pavement Management System: Characterization and Applicability. Master’s Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. Available online: https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/395142226863/Tese_CF.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025). (In Portuguese).

- Pittenger, D.M. Sustainable Airport Pavements. In Climate Change, Energy, Sustainability and Pavements; Gopalakrishnan, K., Steyn, W., Harvey, J., Eds.; Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, I.R.; Silva, F.J.S.; Costa, L.H.G.; Neto, E.D.; Viana, H.R.G. Airport pavement evaluation systems for maintenance strategies development: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Subagio, B.S.; Rahman, H.; Frazila, R.B. Evaluation of the airport pavement condition index in the aircraft lateral wander area. Int. J. GEOMATE 2024, 27, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, H.; Gagnon, J. Comparison analysis of airfield pavement life estimated from different pavement condition indexes. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2021, 147, 04021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.F.C.; Picado Santos, L.G. Maintenance of airport pavements: The use of visual inspection and IRI in the definition of degradation trends. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2019, 20, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chai, G.; Oh, E.; Bell, P. A review of PCN determination of airport pavements using FWD/HWD test. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 16, 908–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeni, A.; Loizos, A. Preliminary evaluation of the ACR-PCR system for reporting the bearing capacity of flexible airfield pavements. Transp. Eng. 2022, 8, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roginski, M.J. Effects of aircraft tire pressures on flexible pavements. In Proceedings of the 23rd World Road Congress of the World Road Association (PIARC), Paris, France, 17–21 September 2007; Volume 2, pp. 1473–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, L.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, Z. Improvement of Boeing bump method considering aircraft vibration superposition effect. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, I.; Santos, B.; Gama, J.; Almeida, P.G. Statistical analysis of an in-vehicle image-based data collection method for assessing airport pavement condition. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Graziano, A.; Ragusa, E.; Marchetta, V.; Palumbo, A. Analysis of an airport pavement management system during the implementation phase. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, M.; Iwanowski, P. Evaluation of asphalt concrete airport pavement conditions based on the airfield pavement condition index (APCI) in scope of flight safety. Aerospace 2020, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, M.; Iwanowski, P. Evaluation of natural airfield pavements condition based on the airfield pavement condition index (APCI). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, P.; Ragnoli, A.; Portas, S.; Santoni, M. Monitor activity for the implementation of a pavement-management system at Cagliari Airport. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.T.; Oh, E.; Chai, G.; Bell, P. An overview of the airport pavement management systems (APMS). Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babashamsi, P.; Khahro, S.H.; Omar, H.A.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Memon, A.M.; Milad, A.; Khan, M.I.; Sutanto, M.H.; Yusoff, N.I.M. Perspective of life-cycle cost analysis and risk assessment for airport pavement in delaying preventive maintenance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babashamsi, P.; Khahro, S.H.; Omar, H.A.; Rosyidi, S.A.P.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Milad, A.; Bilema, M.; Sutanto, M.H.; Yusoff, N.I.M. A comparative study of probabilistic and deterministic methods for the direct and indirect costs in life cycle cost analysis for airport pavements. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizona Department of Transportation—Aeronautics Group. Airport Pavement Management System (APMS) Executive Summary; Arizona Department of Transportation: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2013. Available online: https://azdot.gov/sites/default/files/2018/06/2010-apms-update-executive-summary.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Guidelines and Procedures for Maintenance of Airport Pavements, AC 150/5380–6C; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/airports/resources/advisory_circulars/index.cfm/go/document.current/documentnumber/150_5380-6 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Airport Pavement Management Program (PMP), AC 150/5380–7B; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/150-5380-7B.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Transportation Research Board (TRB). Common Airport Pavement Maintenance Practices: A Synthesis of Airport Practice; Airport Cooperative Research Program Synthesis 22; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Applied Pavement Technology, Inc. Washington Airport Pavement Management Manual; Prepared for the WSDOT Aviation Division and FAA Northwest Mountain Region; Applied Pavement Technology: Urbana, IL, USA, 2019; Available online: https://idea.appliedpavement.com/hosting/washington/reports/2025_WA_APMS_PM_Manual.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Baldo, N.; Rondinella, F.; Celauro, C. Prediction of airport pavement moduli by machine learning methodology using non-destructive field testing data augmentation. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 306, pp. 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Gordoa, J.A.I.; Ortega, J.D.; García, S.; Iriarte, F.J.; Nieto, M. Automatic UAV-based airport pavement inspection using mixed real and virtual scenarios. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Machine Vision (ICMV 2022)—SPIE, Rome, Italy, 18–20 November 2022; Volume 12701, p. 1270118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.A.; Pullen, A. Identification of pavement issues using latent Dirichlet allocation machine learning. In Airfield and Highway Pavements 2023; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, I.; Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G. Pavement inspection in transport infrastructures using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Sustainability 2024, 16, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Studart, A.; Almeida, P. Assessment of Airport Pavement Condition Index (PCI) Using Machine Learning. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietersen, R.A.; Beauregard, M.S.; Einstein, H.H. Automated method for airfield pavement condition index evaluations. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noruzoliaee, M.; Zou, B. Airfield infrastructure management using network-level optimization and stochastic duration modeling. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stache, J.M.; Doyle, J.D.; Hodo, W.D.; Tingle, J.S. Consideration of asphalt viscoelastic behavior effects for airfield flexible pavement evaluation. In Airfield and Highway Pavements 2023; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Advisory Circular 150/5320-6G: Airport Pavement Design and Evaluation; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/150-5320-6G-Pavement-Design.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Parsons, T.A.; Murrell, S.D. Relationship between foreign object debris, roughness, and friction. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2024, 150, 04024035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, H.; Sarkar, R. Airport pavement distress analysis. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2024, 48, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5340-12; Standard Test Method for Airport Pavement Condition Index Surveys. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–54. [CrossRef]

- UFC 3-260-16; Pavement Condition Index Distress Identification Manual for Airfield Pavements. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. House of Representatives, Drone Infrastructure Inspection Grant Act, House Report 117-460; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/committee-report/117th-congress/house-report/460/1 (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Skydio. 2024 FAA Reauthorization and Drones: What You Need to Know. Skydio Blog, 2023. Available online: https://www.skydio.com/blog/2024-faa-reauthorization-and-drones-what-you-need-to-know (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Chase, M.; Gunness, K.; Morris, K.; Berkowitz, S.; Purser, B. Emerging Trends in China’s Development of Unmanned Systems; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR990.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Sourav, M.A.A.; Ceylan, H.; Brooks, C.; Dobson, R.; Kim, S.; Peshkin, D.; Brynick, M. Use of small unmanned aircraft systems in airfield pavement inspection: Implementation and potential. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2401630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourav, M.A.A.; Ceylan, H.; Kim, S.; Brynick, M. Integration of small unmanned aircraft systems and deep learning for efficient airfield pavement crack detection and assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 June 2024; pp. 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, M.T.; Bishop, G.; Saur, V. Using AI and change detection in geospatial UAS airfield pavement inspection for pavement management. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 June 2024; pp. 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, M.T.; Bishop, G.; Saur, V. Experiences gained and benefits from using uncrewed aerial systems to calculate pavement condition index at over 80 airports in the United States. In Proceedings of the Airfield and Highway Pavements 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 14–17 June 2023; pp. 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, M.T.; Bishop, G.; Saur, V.; Lu, S.; Naputi, J.; Serna, D.; Popko, D. Detailed pavement inspection of airports using remote sensing UAS and machine learning of distress imagery. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, 31 July–3 August 2022; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowski, M.; Iwanowski, P. Evaluation of the cement concrete airfield pavement’s technical condition based on the APCI index. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2020, 66, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, P.; Moretti, L. Implementation of a pavement management system for maintenance and rehabilitation of airport surfaces. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieja, M.; Blacha, K.; Wesołowski, M. Assessment method of the deterioration degree of asphalt concrete airport pavements. In Safety and Reliability—Safe Societies in a Changing World; Haugen, S., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018; p. 62018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, M.T. Remaining service life analysis of concrete airfield pavements at Denver International Airport using the FACS method. In Proceedings of the Airfield and Highway Pavements: Efficient Pavements Supporting Transportation’s Future, Bellevue, WA, USA, 30 April–3 May 2008; pp. 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.Y.; Kohn, S.D. Airfield pavement performance prediction and determination of rehabilitation needs. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, Delft, The Netherlands, 23–26 August 1982; Volume 1, pp. 637–652. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Gowda, S.; Gupta, A. Implementation of airfield pavement management system in India. In Recent Advances in Traffic Engineering (RATE 2022); Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 377, pp. 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, J.J. Climate change impacts to arctic airfields. In Proceedings of the Cold Regions Engineering 2024: Sustainable and Resilient Engineering Solutions for Changing Cold Regions, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 27–30 August 2024; pp. 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslan, J.; Cicmanec, L. A system for the automatic detection and evaluation of the runway surface cracks obtained by unmanned aerial vehicle imagery using deep convolutional neural networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, N.M.; Ibraheem, A.T. Developing a frame design for airport pavements maintenance management system. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Cereceda, D.; Medel-Vera, C.; Ortiz, M.; Tramon, J. Roughness and condition prediction models for airfield pavements using digital image processing. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Multi-task learning for pavement disease segmentation using wavelet transform. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, P. Research on airport pavement condition information system. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 15–17 April 2022; pp. 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslan, J.; Cicmanec, L. Setting the flight parameters of an unmanned aircraft for distress detection on the concrete runway. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Military Technologies (ICMT), Brno, Czech Republic, 23–25 June 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gui, X.; Dong, Q.; Tu, S.; Li, S. 3D visualization of airport pavement quality based on BIM and WebGL integration. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2021, 147, 04021024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, A.; Celaya, M.; Jha, V.; Frabizzio, M. Semi-automated method to determine pavement condition index on airfields. In Proceedings of the Airfield and Highway Pavements 2021, Austin, TX, USA, 8–11 June 2021; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G.; Feitosa, I.; Lima, D. Validation of an indirect data collection method to assess airport pavement condition. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V.; Singh, A.P.; Srivastava, A. Quantification of airfield pavement condition using soft-computing technique. World J. Eng. 2020, 17, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.; Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G. Methodology to assess airport pavement condition using GPS, laser, video image and GIS. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Pavement Asset Management (WCPAM 2017), Baveno, Italy, 12–16 June 2017; pp. 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fathalla, S.; El-Desouky, A. Evaluation of pavement surface conditions for Luxor International Airport. Eng. Res. J. 2019, 162, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahagun, L.K.; Karakouzian, M.; Paz, A.; Fuente-Mella, H.D.L. An investigation of geography and climate induced distresses patterns on airfield pavements at US air force installations. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 8721940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbiru, L.; Wei, P.; Harsh, A.; White, J.; Ball, J.E.; Aanstoos, J.; Donohoe, P.; Doyle, J.; Jackson, S.; Newman, J. Runway assessment via remote sensing. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop (AIPR), Washington, DC, USA, 13–15 October 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.A.; Pullen, B.A. Relationship between climate type and observed pavement distresses. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2016, Houston, TX, USA, 26–29 June 2016; pp. 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.-M.; Du, Z.-M.; Yuan, J.; Tang, L. Airfield pavement maintenance and rehabilitation management: Case study of Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport. In Advances in Civil Engineering and Building Materials IV; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.W. Electro-optical sensor evaluation of airfield pavement. In Proceedings of the Airfield and Highway Pavement 2013: Sustainable and Efficient Pavements, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 June 2013; pp. 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Fwa, T.; Chan, W.T. Pavement-distress data collection system based on mobile geographic information system. Transp. Res. Rec. 2004, 1889, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fwa, T.F.; Liu, S.B.; Teng, K.J. Airport pavement condition rating and maintenance-needs assessment using fuzzy logic. In Proceedings of the Airfield Pavements: Challenges and New Technologies, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5–8 August 2003; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, G.R.; Schwartz, C.W.; Witczak, M.W.; Rabinow, S.D. Integrated pavement management system for Kennedy International Airport. J. Transp. Eng. 1992, 118, 666–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.W.; Grau, R.W.; Grogan, W.P.; Hachiya, Y. Performance indications from army airfield pavement management program. In Pavement Management Implementation; ASTM STP 1121; American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Eckrose, R.A.; Reynolds, W.G. Implementation of a pavement management system for Indiana airports—A case history. In Pavement Management Implementation; ASTM STP 1121; American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Beaucham, E.B. Evaluating army airfields. Mil. Eng. 1991, 83, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Covalt, M.R.; Raczkowski, L.; Fisher, M.; Truschke, C.; Brynick, M. Status of airport pavement conditions in the United States. In Pavement and Asset Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; p. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R.; McArdle, G. What Makes Big Data, Big Data? Exploring the Ontological Characteristics of 26 Datasets. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 2053951716631130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, M. Research Challenges of Big Data. Serv. Oriented Comput. Appl. 2019, 13, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, J. A Brief Introduction on Big Data 5Vs Characteristics and Hadoop Technology. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 48(C), 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, G.L.; O’Leary, D.E. V-Matrix: A Wave Theory of Value Creation for Big Data. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2022, 47, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nateghinia, E.; Miranda-Moreno, L.F.; Sun, L. Pavement distress detection using convolutional neural networks (CNNs): A case study in Montreal, Canada. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeagyei, A.; Ademolake, T.E.; Adom-Asamoah, M. Evaluation of deep learning models for classification of asphalt pavement distresses. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2180641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, Z. Optimizing CNN for pavement distress detection via edge-enhanced multi-scale feature fusion. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bei, Z.; Ling, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L. Research on high-precision recognition model for multi-scene asphalt pavement distresses based on deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Phase | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Initial search in the Scopus database was conducted using terms extracted from the titles, abstracts, and keywords of relevant articles. The following combined search expressions were applied: (“pavement inspection” OR “pavement condition” OR “pavement evaluation” OR “machine learning” OR “big data” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “multifunctional vehicles” OR “laser scanning” OR “Pavement Condition Index” OR “PCI”) AND (“airport pavement” OR “airfield pavement” OR “runway pavement management”). |

| 2 | Refined of results by subject areas (engineering, materials science, computer science), document type (article, conference paper, conference review, review), publication status (final stage), and language (English). |

| 3 | Abstract screening was performed to exclude studies focused solely on structural evaluation (e.g., deflectometer tests) or non-airport pavements. |

| 4 | Full-text review of the screened documents, with retrieval of non-open-access articles through author contact when necessary. |

| 5 | Final selection of documents that explicitly describe inspection activities or data collection procedures related to airport pavements (e.g., case studies). |

| Technique Type | Data Processing Techniques | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric and visual techniques | Photogrammetry/Orthoimage/DEM | High |

| Georeferencing and spatial indexing | Moderate | |

| AI and computer vision techniques | Deep learning (e.g., CNNs, YOLO, etc.) | High 1 |

| Semantic segmentation (e.g., DeepLab, FPN, etc.) | High | |

| Statistical and model-based methods | Basic statistical modeling (e.g., linear regression) | Moderate |

| Advanced and intermediate statistical modelling (e.g., multivariate analysis, ANOVA, etc.) | Low | |

| Fuzzy logic/Soft computing/AHP | Moderate | |

| PAVER/MicroPAVER/GIS | High 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feitosa, I.; Santos, B.; Almeida, P.G. Automated and Intelligent Inspection of Airport Pavements: A Systematic Review of Methods, Accuracy and Validation Challenges. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040183

Feitosa I, Santos B, Almeida PG. Automated and Intelligent Inspection of Airport Pavements: A Systematic Review of Methods, Accuracy and Validation Challenges. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040183

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeitosa, Ianca, Bertha Santos, and Pedro G. Almeida. 2025. "Automated and Intelligent Inspection of Airport Pavements: A Systematic Review of Methods, Accuracy and Validation Challenges" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040183

APA StyleFeitosa, I., Santos, B., & Almeida, P. G. (2025). Automated and Intelligent Inspection of Airport Pavements: A Systematic Review of Methods, Accuracy and Validation Challenges. Future Transportation, 5(4), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040183