Molecular Detection of Helminths in Stool Samples: Methods, Challenges, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Helminth Detection by PCR and the Identification of Resistance

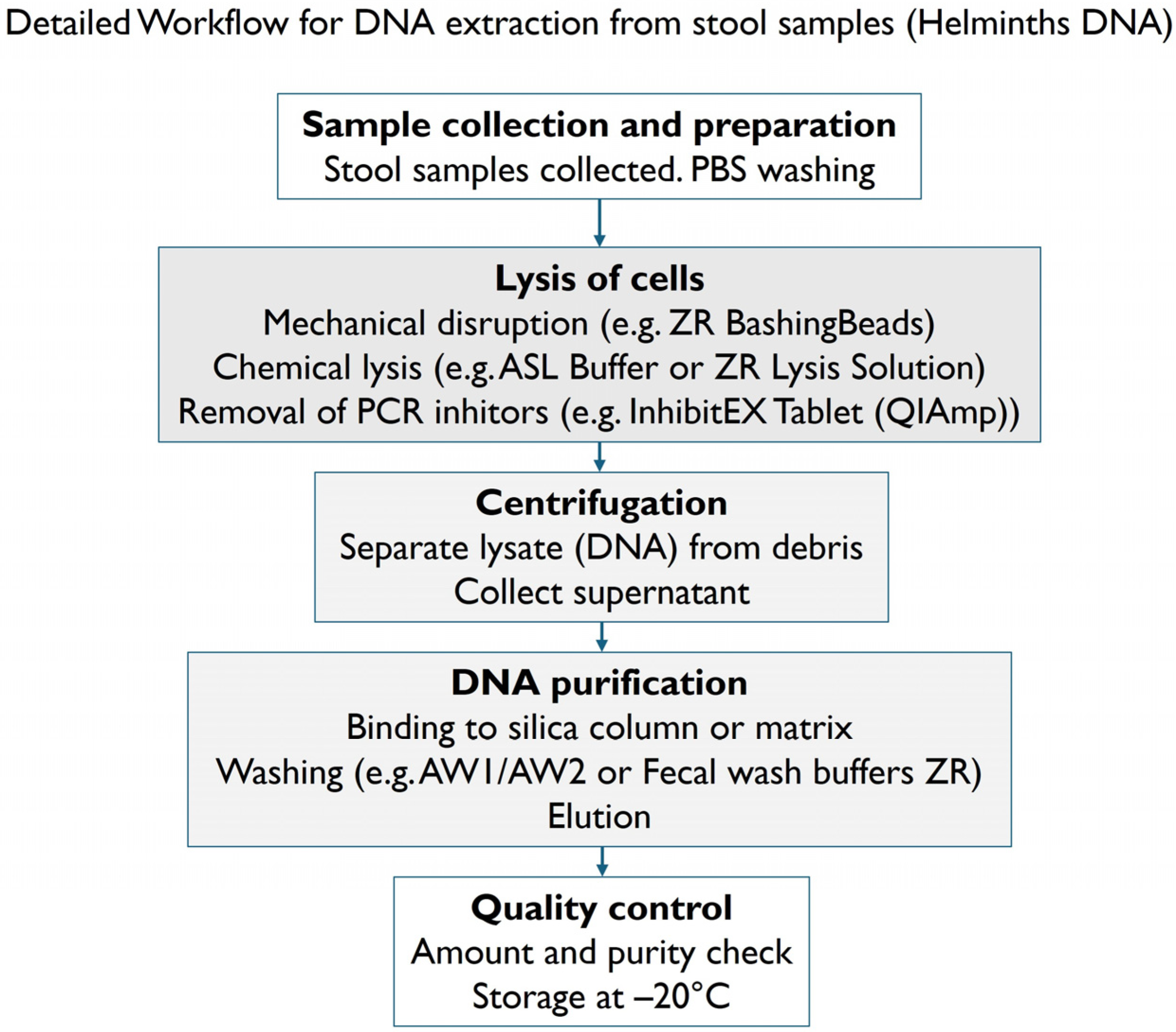

3.2. Methodological Challenges for Helminth DNA Extraction from Stool Samples

3.3. Helminth qPCR Reagents

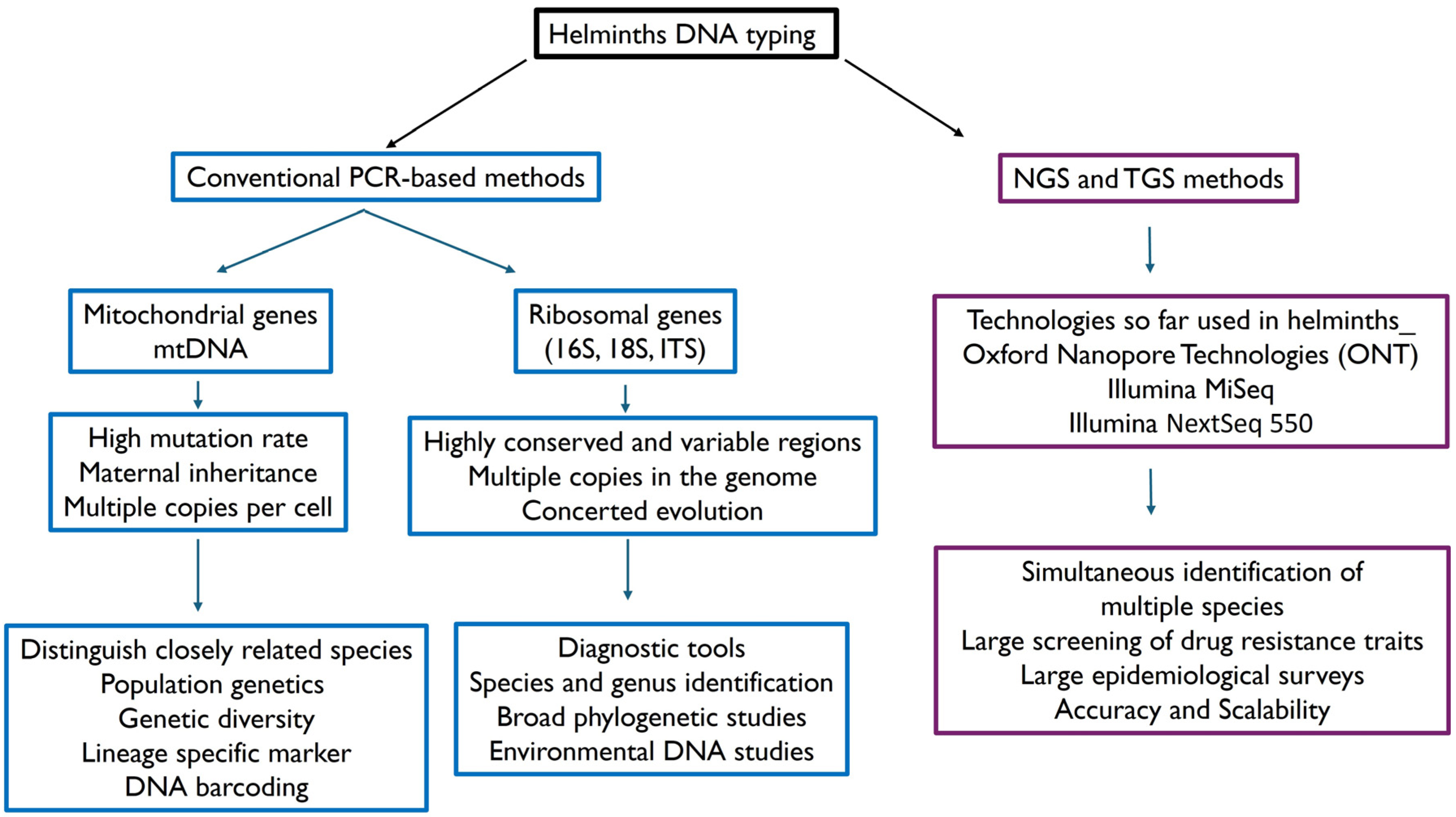

3.4. Some Examples of Molecular Typing of Helminth DNA: Opportunities and Novel Approaches

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tarafder, M.R.; Carabin, H.; Joseph, L.; Balolong, E.; Olveda, R.; McGarvey, S. Estimating the sensitivity and specificity of Kato-Katz stool examination technique for detection of hookworms, Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura infections in humans in the absence of a ‘gold standard’. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacad, J.L.J.; Yurlova, N.I.; Tanabe-Hosoi, S.; Urabe, M. Trematode species detection and quantification by environmental dna-qpcr assay in lake chany, russia. J. Parasitol. 2024, 110, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletzky, L.; Eberhardt, K.A.; Hergeth, J.; Stelzl, D.R.; Manego, R.Z.; Kreuzmair, R.; Burger, G.; Mischlinger, J.; McCall, M.B.B.; Mombo-Ngoma, G.; et al. Analysis of diagnostic test outcomes in a large loiasis cohort from an endemic region: Serological tests are often false negative in hyper-microfilaremic infections. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshipour, F.; Zibaei, M.; Rokni, M.B.; Miahipour, A.; Firoozeh, F.; Beheshti, M.; Beikzadeh, L.; Alizadeh, G.; Aryaeipour, M.; Raissi, V. Comparative evaluation of real-time PCR and ELISA for the detection of human fascioliasis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessler, M.J.; Cyrs, A.; Krenzke, S.C.; Mahmoud, E.S.; Sikasunge, C.; Mwansa, J.; Lodh, N. Detection of duo-schistosome infection from filtered urine samples from school children in Zambia after MDA. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyan, W.K.; Pulkkila, B.R.; Dyra, C.E.; Price, M.; Naples, J.M.; Quartey, J.K.; Anang, A.K.; Lodh, N. Assessment of dual schistosome infection prevalence from urine in an endemic community of Ghana by molecular diagnostic approach. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2020, 9, e00130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvi, S.; Jacob, J.; Mina, A.; Lyons, M. Detection of rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) infection by real-time PCR from the peripheral blood of animals: A preliminary study. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasser, R.B.; Chilton, N.B.; Hoste, H.; Beveridge, I. Rapid sequencing of rDNA from single worms and eggs of parasitic helminths. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 2525–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanova, E.A.; Semenova, S.K.; Benediktov, I.; Ryskov, A.P. Use of polymerase chain reaction for identifying helminth DNA from the species Trichinella, Fasciola, Echinococcus, Nematodirus, Taenia. Parazitologiia 1997, 31, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, L.A.; Dias-Neto, E.; Rabello, A. Detection by polymerase chain reaction of Schistosoma mansoni DNA in human serum and feces. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuphisut, O.; Yoonuan, T.; Sanguankiat, S.; Chaisiri, K.; Maipanich, W.; Pubampen, S.; Komalamisra, C.; Adisakwattana, P. Triplex polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of major soil-transmitted helminths, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, in fecal samples. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 45, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tun, S.; Ithoi, I.; Mahmud, R.; Samsudin, N.I.; Heng, C.K.; Ling, L.Y. Detection of Helminth Eggs and Identification of Hookworm Species in Stray Cats, Dogs and Soil from Klang Valley, Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilotte, N.; Papaiakovou, M.; Grant, J.R.; Bierwert, L.A.; Llewellyn, S.; McCarthy, J.S.; A Williams, S. Improved PCR-Based Detection of Soil Transmitted Helminth Infections Using a Next-Generation Sequencing Approach to Assay Design. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.A.; Chua, K.H. A conventional multiplex PCR for the detection of four common soil-transmitted nematodes in human feces: Development and validation. Trop. Biomed. 2022, 39, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, S.K.; A Romanova, E.; Ryskov, A.P. Genetic differentiation of helminths on the basis of data of polymerase chain reaction using random primers. Genetika 1996, 32, 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Tatonova, Y.V.; Chelomina, G.N.; Besprosvannykh, V.V. Genetic diversity of nuclear ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA sequence in Clonorchis sinensis Cobbold, 1875 (Trematoda: Opisthorchidae) from the Russian Far East. Parasitol. Int. 2012, 61, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, J.J.; Canales, M.; Polman, K.; Ziem, J.; Brienen, E.A.; Polderman, A.M.; van Lieshout, L. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, F.; Mora, N.; Incani, R.N.; Jesus, J.; Méndez, N.; Mujica, R.; Trosel, H.; Ferrer, E. Comparison of different PCR amplification targets for molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis. J. Helminthol. 2023, 97, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, S.; Pantano, M.L.; Kamenetzky, L.; Malandrini, J.B.; Soria, C.C.; Velásquez, J.N. Molecular diagnosis of natural fasciolosis by DNA detection in sheep faeces. Acta Parasitol. 2015, 60, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Hove, R.J.; Verweij, J.J.; Vereecken, K.; Polman, K.; Dieye, L.; van Lieshout, L. Multiplex real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium infection in stool samples collected in northern Senegal. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 102, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, C.A.; Blouin, M.S.; Yowell, C.A.; Dame, J.B. Suitability of mitochondrial DNA for assaying interindividual genetic variation in small helminths. J. Parasitol. 1992, 78, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Blair, D.; McManus, D.P. Mitochondrial genomes of human helminths and their use as markers in population genetics and phylogeny. Acta Trop. 2000, 77, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diawara, A.; Drake, L.J.; Suswillo, R.R.; Kihara, J.; Bundy, D.A.P.; Scott, M.E.; Halpenny, C.; Stothard, J.R.; Prichard, R.K. Assays to detect beta-tubulin codon 200 polymorphism in Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, L.F.V.; Medeiros, C.D.S.; Zuccherato, L.W.; Alves, W.P.; De Oliveira, V.N.G.M.; Da Silva, V.J.; Miranda, G.S.; Fujiwara, R.T.; Rabelo, É.M.L. First identification of the benzimidazole resistance-associated F200Y SNP in the beta-tubulin gene in Ascaris lumbricoides. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Oliveira, V.N.G.; Zuccherato, L.W.; Dos Santos, T.R.; Rabelo, É.M.L.; Furtado, L.F.V. Detection of Benzimidazole Resistance-Associated Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Beta-Tubulin Gene in Trichuris trichiura from Brazilian Populations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 107, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotte, N.; Maasch, J.R.M.A.; Easton, A.V.; Dahlstrom, E.; Nutman, T.B.; Williams, S.A. Targeting a highly repeated germline DNA sequence for improved real-time PCR-based detection of Ascaris infection in human stool. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño, C.; Patarroyo, M.A. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification as point-of-care diagnosis for neglected parasitic infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.; Ahmad, F.J.; Kar, S. Recent advances in loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for rapid and efficient detection of pathogens. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodh, N.; Mikita, K.; Bosompem, K.M.; Anyan, W.K.; Quartey, J.K.; Otchere, J.; Shiff, C.J. Point of care diagnosis of multiple schistosome parasites: Species-specific DNA detection in urine by loop-mediated iso-thermal amplification (LAMP). Acta Trop. 2017, 173, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuera, A.; Villamizar, X.; Herrera, G.; Giraldo, J.C.; Vasquez-A, L.R.; Urbano, P.; Villalobos, O.; Tovar, C.; Ramírez, J.D. Molecular detection and genotyping of intestinal protozoa from different biogeographical regions of Colombia. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, R.; Johansen, M.V.; Utzinger, J. Diagnostic dilemmas in helminthology: What tools to use and when? Trends Para-Sitol. 2009, 25, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirungruang, S.; Mahajindawong, B.; Nimitpanya, P.; Bunkasem, U.; Ayuyoe, P.; Nuchprayoon, S.; Sanprasert, V. Comparative Study of DNA Extraction Methods for the PCR Detection of Intestinal Parasites in Human Stool Samples. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsepasi, H.; Persson, S.; Struve, C.; Andersen, L.O.B.; Petersen, A.M.; Krogfelt, K.A. Microbial diversity in fecal samples depends on DNA extraction method: easyMag DNA extraction compared to QIAamp DNA stool mini kit extraction. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illiano, S.; Ciuca, L.; Bosco, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Maurelli, M.P. Comparison of different molecular protocols for the detection of Uncinaria stenocephala infection in dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2024, 330, 110249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.; Hahn, A.; Verweij, J.J.; Leboulle, G.; Landt, O.; Strube, C.; Kann, S.; Dekker, D.; May, J.; Frickmann, H.; et al. Differing Effects of Standard and Harsh Nucleic Acid Extraction Procedures on Diagnostic Helminth Real-Time PCRs Applied to Human Stool Samples. Pathogens 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devyatov, A.A.; Davydova, E.E.; Luparev, A.R.; Karseka, S.A.; Shuryaeva, A.K.; Zagainova, A.V.; Shipulin, G.A. Design of a Protocol for Soil-Transmitted Helminths (in Light of the Nematode Toxocara canis) DNA Extraction from Feces by Combining Commercially Available Solutions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayana, M.; Cools, P.; Mekonnen, Z.; Biruksew, A.; Dana, D.; Rashwan, N.; Prichard, R.; Vlaminck, J.; Verweij, J.J.; Levecke, B. Comparison of four DNA extraction and three preservation protocols for the molecular detection and quantification of soil-transmitted helminths in stool. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, D.; Pokhrel, N. Effect of incorporation of bead-beating during DNA extraction for quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Trichuris trichiura in stool samples in community settings: A systematic review. J. Helminthol. 2023, 97, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, K.J.L.; Calegar, D.; Carvalho-Costa, F.; Jaeger, L. Kato-Katz thick smears as a DNA source of soil-transmitted helminths. J. Helminthol. 2018, 94, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuni, M.; Muhi, J.; Othman, N.; Verweij, J.J.; Ahmad, M.; Miswan, N.; Rahumatullah, A.; Aziz, F.A.; Zainudin, N.S.; Noordin, R. A pentaplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of four species of soil-transmitted helminths. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; Blair, D.; McManus, D.P. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992, 54, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.M.; Dias, A.K.K.; Dias, F.E.F.; Aoki, S.M.; de Paula, H.B.; Lima, L.G.F.; Garcia, J.F. Taenia saginata: Differential diagnosis of human taeniasis by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay. Exp. Parasitol. 2005, 110, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autier, B.; Gangneux, J.P.; Robert-Gangneux, F. Evaluation of the Allplex GI-Helminth(I) Assay, the first marketed multiplex PCR for helminth diagnosis. Parasite 2021, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areekul, P.; Putaporntip, C.; Pattanawong, U.; Sitthicharoenchai, P.; Jongwutiwes, S. Trichuris vulpis and T. trichiura infections among schoolchildren of a rural community in northwestern Thailand: The possible role of dogs in disease transmission. Asian Biomed. 2010, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massolo, A.; Valli, D.; Wassermann, M.; Cavallero, S.; D’AMelio, S.; Meriggi, A.; Torretta, E.; Serafini, M.; Casulli, A.; Zambon, L.; et al. Unexpected Echinococcus multilocularis infections in shepherd dogs and wolves in south-western Italian Alps: A new endemic area? Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2018, 7, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandasegui, J.; Grau-Pujol, B.; Cambra-Pelleja, M.; Escola, V.; Demontis, M.A.; Cossa, A.; Jamine, J.C.; Balaña-Fouce, R.; van Lieshout, L.; Muñoz, J.; et al. Improving stool sample processing and pyrosequencing for quantifying benzimidazole resistance alleles in Trichuris trichiura and Necator americanus pooled eggs. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, L.G.; Atapattu, U.; Young, N.D.; Traub, R.J.; Colella, V. Development and validation of a long-read metabarcoding platform for the detection of filarial worm pathogens of animals and humans. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, G.; Ghafar, A.; Bauquier, J.; Beasley, A.; Ling, E.; Gauci, C.G.; El-Hage, C.; Wilkes, E.J.; McConnell, E.; Carrigan, P.; et al. Prevalence and diversity of ascarid and strongylid nematodes in Australian Thoroughbred horses using next-generation sequencing and bioinformatic tools. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 323, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, E.; Masu, G.; Chisu, V.; Cappai, S.; Masala, G.; Loi, F.; Piseddu, T. Environmental Contamination by Echinococcus spp. Eggs as a Risk for Human Health in Educational Farms of Sardinia, Italy. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramenko, R.W.; Redman, E.M.; Lewis, R.; Yazwinski, T.A.; Wasmuth, J.D.; Gilleard, J.S. Exploring the Gastrointestinal “Nemabiome”: Deep Amplicon Sequencing to Quantify the Species Composition of Parasitic Nematode Communities. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaiakovou, M.; Littlewood, D.T.J.; Doyle, S.R.; Gasser, R.B.; Cantacessi, C. Worms and bugs of the gut: The search for diagnostic signatures using barcoding, and metagenomics–metabolomics. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaiakovou, M.; Waeschenbach, A.; Ajibola, O.; Ajjampur, S.S.; Anderson, R.M.; Bailey, R.; Benjamin-Chung, J.; Cambra-Pellejà, M.; Caro, N.R.; Chaima, D.; et al. Global diversity of soil-transmitted helminths reveals population-biased genetic variation that impacts diagnostic targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Mewara, A.; Lakshmi, P.; Guleria, S.; Khurana, S. Evaluation of loop mediated isothermal amplification, quantitative real-time PCR, conventional PCR methods for identifying Ascaris lumbricoides in human stool samples. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 112, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, M.; Ramanujam, K.; Ajjampur, S.S.R. Molecular Tools for Diagnosis and Surveillance of Soil-Transmitted Helminths in Endemic Areas. Parasitologia 2021, 1, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Locus | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) regions | ITS1 and ITS2 | ITS regions are found in ribosomal DNA and provide high species specificity. These regions are commonly used for differentiating species like Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale [14]. ITS has been typed in Trichinella, Fasciola hepatica, Cysticerus ovis, Echinococcus granulosus, Nematodirus spathiger [15] and Clonorchis sinensis [16]. |

| 18S rRNA gene | 18S rRNA | This gene is highly conserved across eukaryotes but contains enough variation to distinguish between species. It is used in assays detecting Strongyloides stercoralis and other helminths [17,18]. |

| Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I | COI | The COI gene is part of the mitochondrial DNA and frequently used for species identification due to its high level of sequence variability among different species. Largely used in first assays for cestode identification and Schistosoma mansoni [19,20]. |

| NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 | ND1 | The ND1 gene is part of the mitochondrial genome and is particularly useful for distinguishing closely related species. It is used in targeted assays for detecting Ascaris, Onchocerca, Schistosoma and others [21,22]. |

| Beta tubulin gene | β-tubulin genes | The beta tubulin gene is used to detect helminths such as Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides [23]. Mutations in this gene are also associated with resistance to benzimidazole drugs [24,25]. |

| High copy Number Non-Coding Repetitive DNA Elements | Various | High copy non-coding repetitive DNA sequences enhance the sensitivity of detection since they are present in multiple copies in the genome. There are highly sensitive PCR and qPCR assays for detecting soil-transmitted helminths as Ascaris lumbricoides and other helminths [13,26]. |

| Step | Factor | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DNA extraction | Sample heterogeneity | Stool contains a complex mixture of substances including dietary residues, bacteria and other organic materials which can interfere with DNA extraction |

| DNA extraction/PCR amplification | Inhibitory substances | Bile salts, complex polysaccharides, humic acids and phenolic compounds can inhibit the PCR reaction leading to false-negative results |

| PCR amplification | Genetic variability | Helminths exhibit genetic variability which can affect the specificity of PCR primers and probes. Incorrect primer design can lead to cross-reactivity with non-target species. |

| PCR amplification | High amounts of non-target DNA | Feces contains a vast amount of microbial DNA and RNA derived from gut microbiota. The presence of non-target DNA can overwhelm the PCR reaction reducing sensitivity. Specificity in primer design and the use of qPCR can help to differentiate target DNA from background DNA. |

| Brand/Kit Name | Manufacturer | Sample Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Stool | Fast processing time, high DNA yield, inhibitor removal. Enrich host DNA |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kits | QIAGEN | Stool | Fast processing time, high DNA yield, inhibitor removal. Enrich microbial DNA |

| ZR Fecal DNA MiniPrep | Zymo Research | Stool, gut material | Inhibitor removal, bead-beating step, easy to use spin column format |

| NucleoSpin Soil | Macherey-Nagel | Soil, stool | Effective inhibitor removal, broad sample compatibility |

| Stool DNA Isolation Kit | Norgen Biotek | Stool | High sensitivity for low-DNA samples |

| GeneJET Genomic DNA purification kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Various including stool | Simple protocol, broad compatibility with various sample type |

| PowerSoil DNA isolation kit | QIAGEN | Soil, stool | Ideal for samples with high inhibitor content. Bead-beating step designed to lyse tough cells. |

| MAgNA Pure LC DNA isolation kit | Roche | Stool | Employs bead beating for the mechanical disruption of cells in faecal samples. High throughput, automation compatible |

| Parasite Name | Target Gene/Region | PCR Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris lumbricoides | Internal Transcribed Spacer 1 (ITS1) | Multiplex | Phuphisut et al., 2014 [11] |

| Trichuris trichiura | Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 (ITS2) | Multiplex | Phuphisut et al., 2014 [11] |

| Necator americanus | 18S rRNA | Multiplex | Phuphisut et al., 2014 [11] |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 18S rRNA | Singleplex | Verweij et al., 2009 [17] |

| Schistosoma mansoni | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) | Singleplex | Pontes et al., 2002 [10] |

| Echinococcus granulosus | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) | Singleplex | Bowles et al., 1992 [41] |

| Taenia solium | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) | Singleplex | Nunes et al., 2005 [42] |

| Kit Name | Manufacturer | Target Helminths | Description | PCR Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastTrack Helminth Detection Kit | FastTrack Diagnostics | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, Strongyloides stercoralis | Multiplex PCR kit designed for the detection of common soil-transmitted helminths in stool samples. | Multiplex PCR |

| RIDA®GENE Parasitic Stool Panel | R-Biopharm AG | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Strongyloides stercoralis | Multiplex real-time PCR kit for the detection of multiple helminth species in stool samples. | Multiplex Real-Time PCR |

| GeneXpert® Strongyloides | Cepheid | Strongyloides stercoralis | Real-time PCR test for the detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in stool samples, using the GeneXpert system. | Singleplex Real-Time PCR |

| BioGene Helminth Panel | BioGene | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus | A comprehensive multiplex PCR panel for the detection of common soil-transmitted helminths in stool samples. | Multiplex PCR |

| RealStar® Helminth PCR Kit | Altona Diagnostics | Schistosoma spp., Fasciola spp., Opisthorchis spp. | Real-time PCR kit for the detection of various helminths in stool and tissue samples. | Multiplex Real-Time PCR |

| Amplidiag® Bacterial and Parasite Panel | Mobidiag | Schistosoma spp., Strongyloides stercoralis, Ascaris lumbricoides | Multiplex PCR kit for simultaneous detection of bacteria and helminths in stool samples. | Multiplex PCR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

De Vivero, M.M.; Acevedo, N.; Cavallero, S.; D’Amelio, S. Molecular Detection of Helminths in Stool Samples: Methods, Challenges, and Applications. Parasitologia 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010003

De Vivero MM, Acevedo N, Cavallero S, D’Amelio S. Molecular Detection of Helminths in Stool Samples: Methods, Challenges, and Applications. Parasitologia. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Vivero, María M., Nathalie Acevedo, Serena Cavallero, and Stefano D’Amelio. 2026. "Molecular Detection of Helminths in Stool Samples: Methods, Challenges, and Applications" Parasitologia 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010003

APA StyleDe Vivero, M. M., Acevedo, N., Cavallero, S., & D’Amelio, S. (2026). Molecular Detection of Helminths in Stool Samples: Methods, Challenges, and Applications. Parasitologia, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010003