Antibiotic-Mediated Microbiota Depletion of Aedes aegypti Gut Bacteria Modulates Susceptibility to Entomopathogenic Fungal Infection and Modifies Developmental Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mosquito Collection and Maintenance

2.2. Fungal Isolate

2.3. Preparation of Conidia

2.4. Antibiotic Treatments

2.5. Evaluation of Aedes aegypti Mid-Gut Bacterial Populations Following Antibiotic Treatment

- Sucrose (control);

- Sucrose + antibiotic for 3 days;

- Sucrose + antibiotic (for 3 days) and then 3 days offering sucrose without antibiotic;

- Sucrose + antibiotic (for 3 days) and then 6 days offering sucrose without antibiotic;

- Sucrose + antibiotic (for 3 days) and then 9 days offering sucrose without antibiotic.

2.6. Blood Feeding

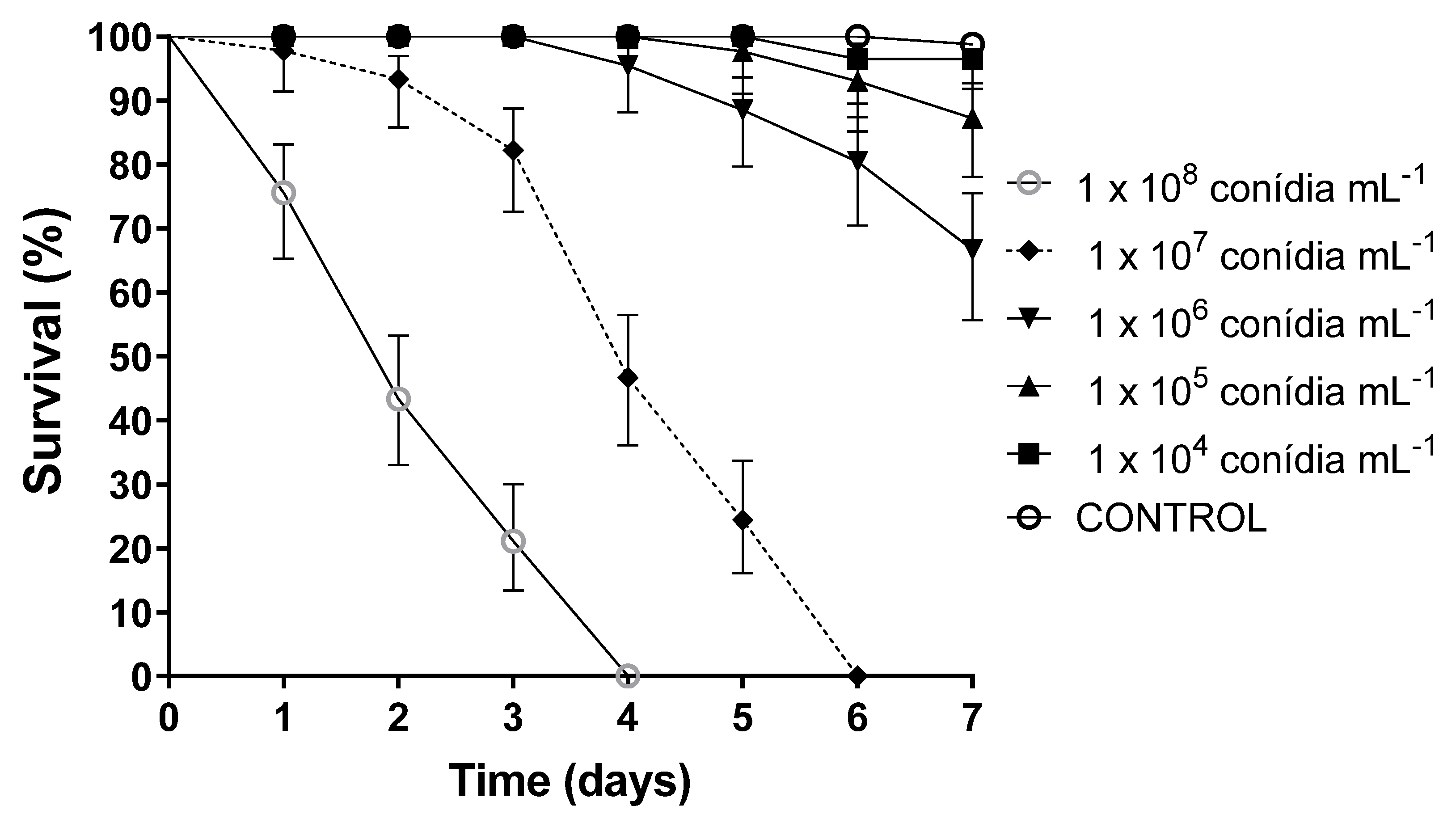

2.7. Selection of Fungal Concentrations for Use in Subsequent Bioassays

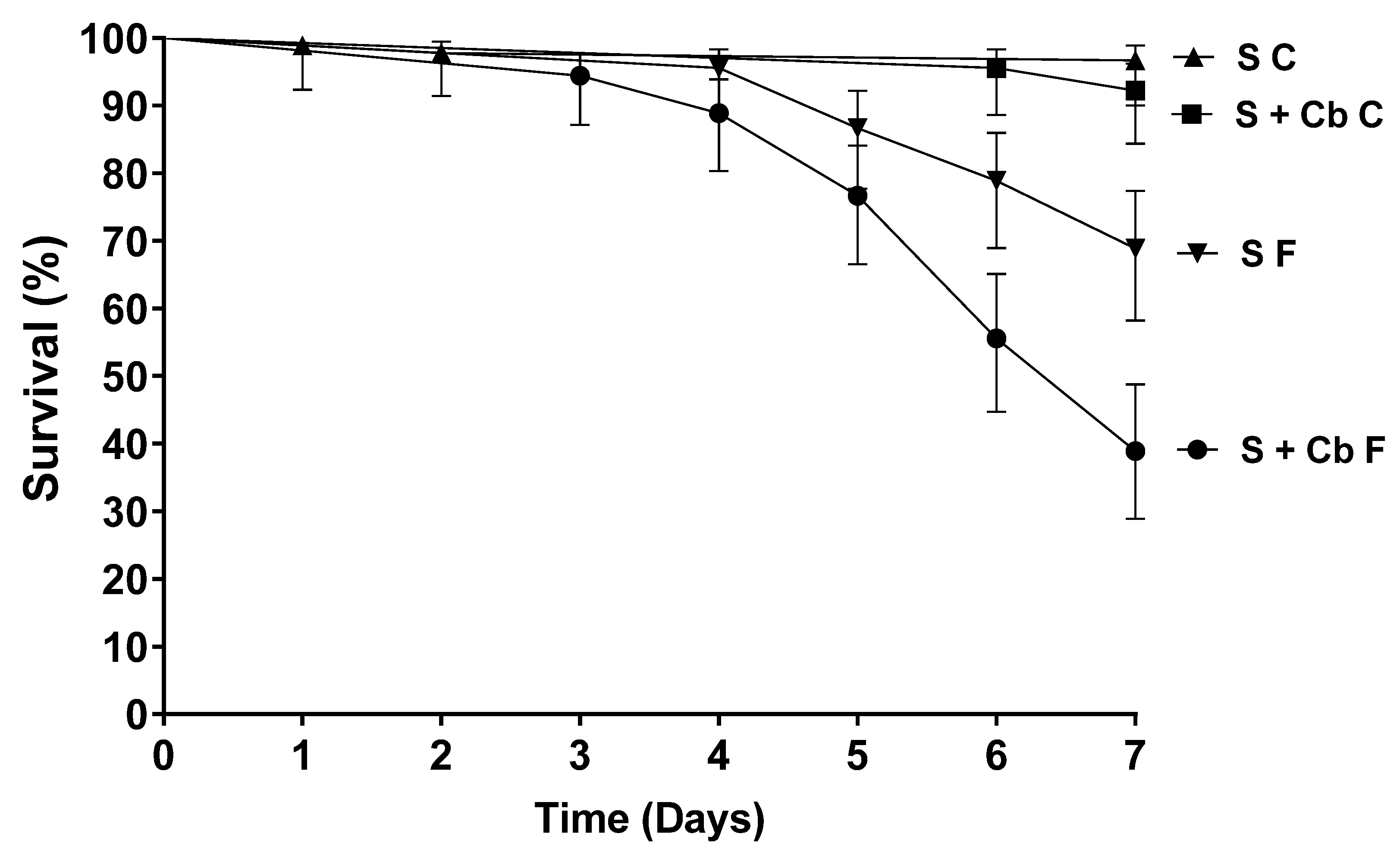

2.8. Virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae When Tested Against Female Aedes aegypti Previously Treated with Antibiotics

- Females offered S + Cb and then sprayed with the fungus (F) (S + Cb F);

- Females offered S and then sprayed with the fungus (S + F);

- Females offered S + Cb and then sprayed with TW (Tween control = C) (S + Cb C);

- Females offered S and sprayed with TW (S C).

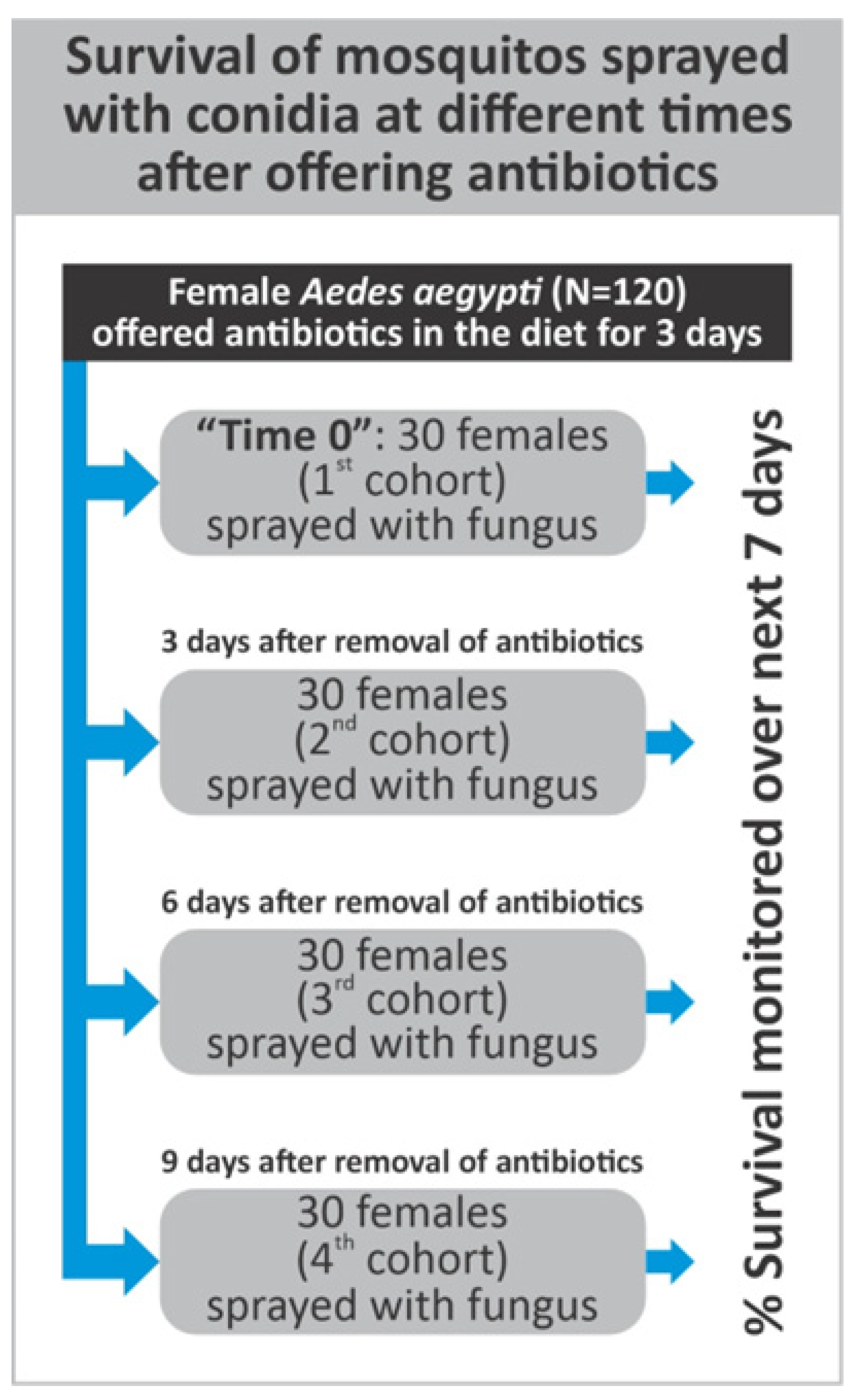

2.9. Survival of Aedes aegypti Females Exposed to Metarhizium anisopliae at Different Periods After Antibiotic Treatment

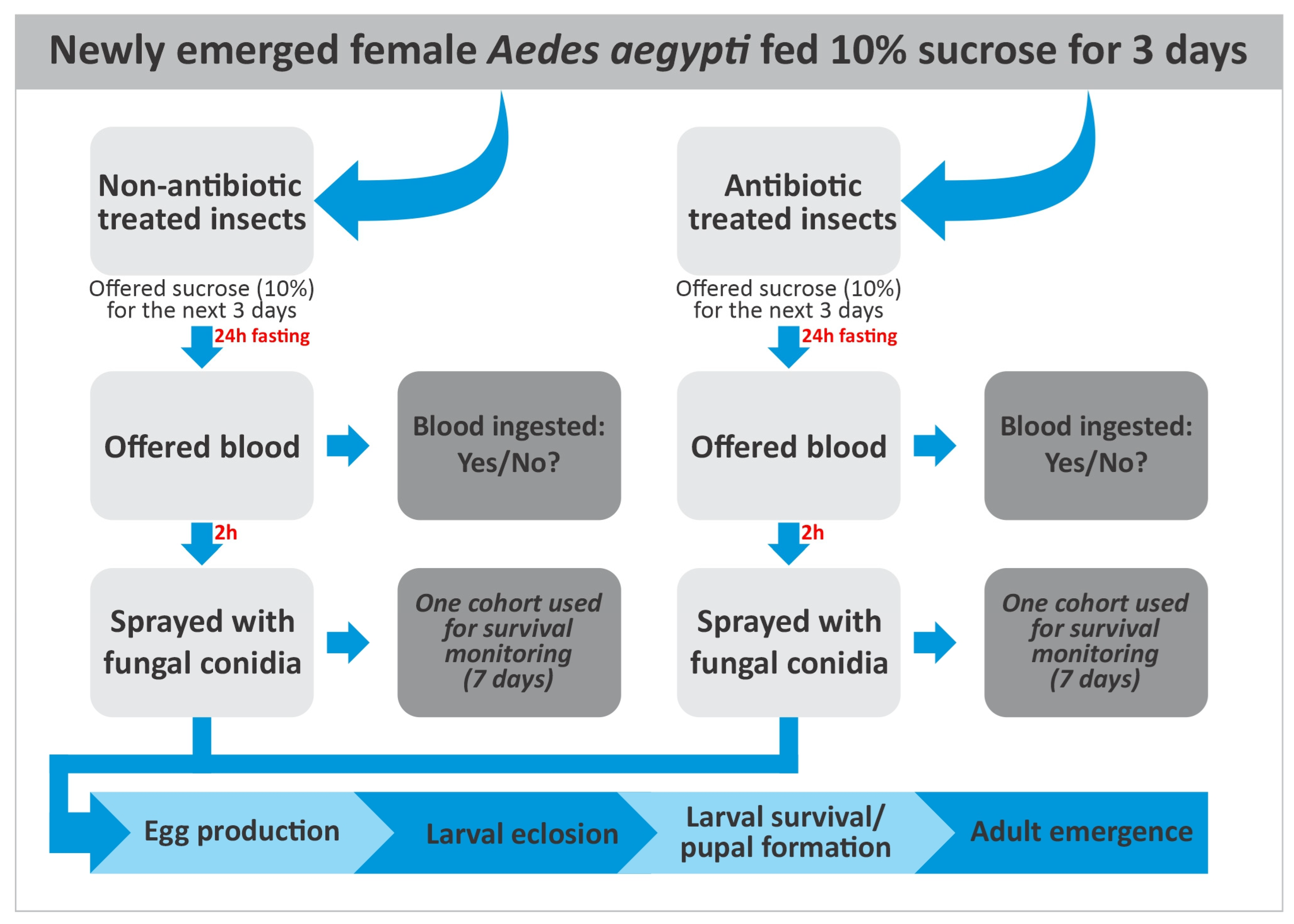

2.10. The Effect of Antibiotics on Aedes aegypti Blood-Feeding Propensity

2.11. The Effects of Fungal Infection and Antibiotic Treatment on Egg Production

- Females offered S + Cb + B and then sprayed with fungus;

- Females offered S + B and then sprayed with fungus;

- Females offered S + Cb + B and then sprayed with TW;

- Females offered S + B and then sprayed with TW.

2.12. Egg, Larval, and Pupal Viability

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Presence of Antibiotics in the Diet Did Not Affect the Blood-Feeding Propensity of Aedes aegypti Females

3.2. Antibiotics Reduce Bacterial Populations in the Mosquito Intestine

3.3. Virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae Against Aedes aegypti Females

3.4. Increased Susceptibility of Aedes aegypti to Metarhizium Anisopliae After Females Had Been Offered Antibiotics

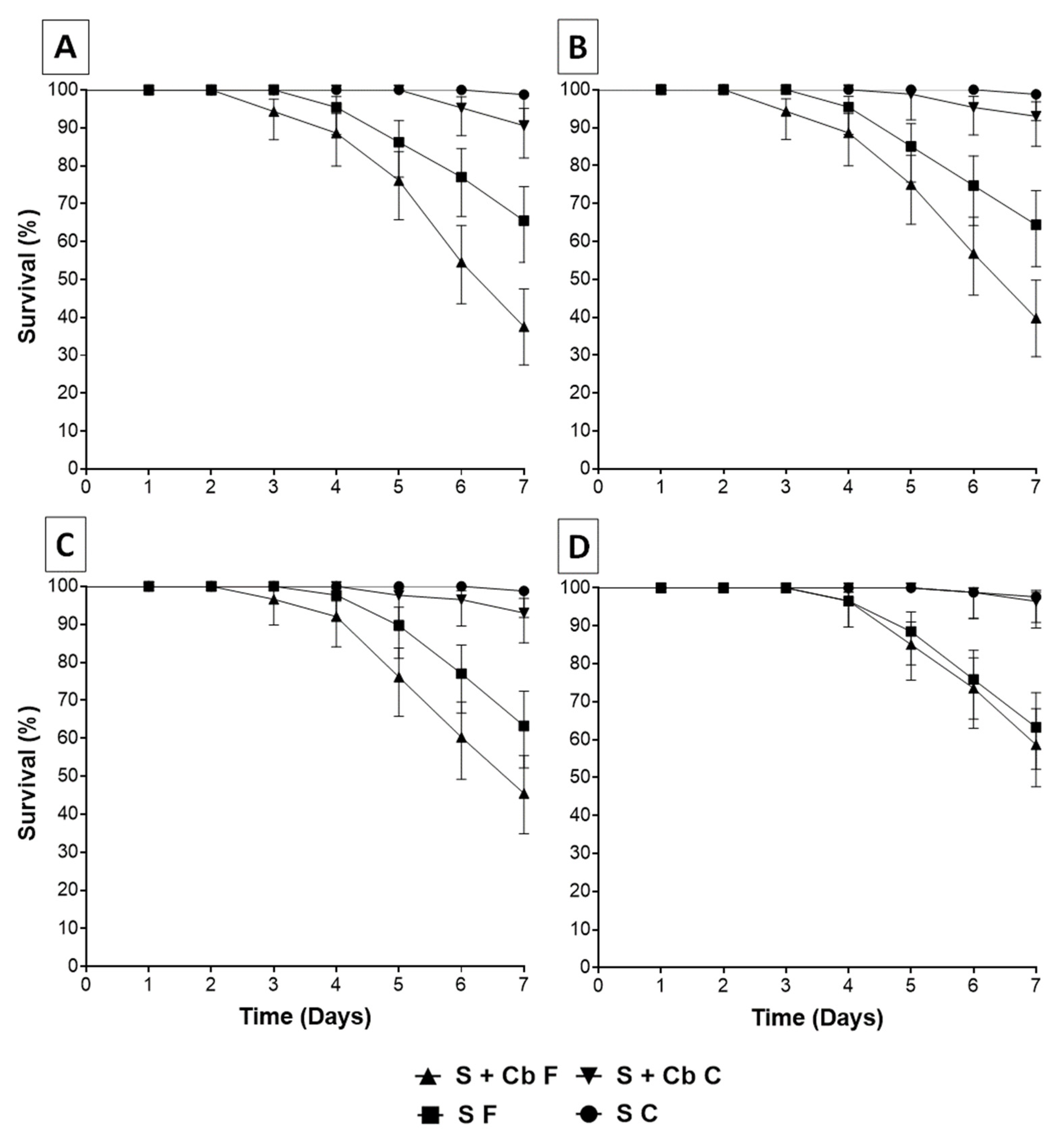

3.5. Survival of Aedes aegypti Females Sprayed with Metarhizium anisopliae Conidia at Different Periods After Antibiotic Treatment

3.6. Aedes aegypti Oviposition Rates Following Different Treatments

3.7. Development from Eggs to Adults Following Different Treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bti | Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis |

| EPF | Entomopathogenic fungi |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| LED | lllumination light-emitting diode |

| SDA | Sabouraud dextrose agar |

| MR-5 | Mycoharvester® |

| S | Sucrose |

| Cb | Carbenicillin |

| F | Fungus |

| TW | Tween 80 |

| C | Control |

| B | Blood |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| BHI | Brain and heart infusion media |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| S50 | Median survival time in days |

| glm | Generalized linear model |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| NA | Not applicable |

| REL2 | Defense gene |

| AMP | Antimicrobial peptides |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Dengue—Global Situation. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON518 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Yellow Fever Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/yellow-fever (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Chikungunya Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Zika Virus Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zika-virus (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Powell, J.R.; Tabachnick, W.J. History of domestication and spread of Aedes aegypti: A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, M.U.; Sinka, M.E.; Duda, K.A.; Mylne, A.Q.; Shearer, F.M.; Barker, C.M.; Moore, C.G.; Carvalho, R.G.; Coelho, G.E.; Wim Van Bortel, W.G.; et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. eLife 2015, 4, e08347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, L.; Scott, T.W.; Gubler, D.J. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukiato, F.; Shriram, A.N.; Sugumaran, M. Eggs of the mosquito Aedes aegypti survive desiccation by rewiring their polyamine and lipid metabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Neto, J.A.; Powell, J.R.; Bonizzoni, M. Aedes aegypti vector competence studies: A review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 67, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatem, A.J.; Hay, S.I.; Rogers, D.J. Global traffic and disease vector dispersal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 6242–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue, urbanization and globalization: The unholy trinity of the 21st century. Trop. Med. Health 2011, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macoris, M.L.G.; Andrighetti, M.T.M.; Takaku, L.; Glasser, C.M.; Garbeloto, V.C.; Bracco, J.E. Resistance of Aedes aegypti from the state of São Paulo, Brazil, to organophosphate insecticides. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, I.R.; Martins, A.J.; Viana-Medeiros, P.F.; Lima, J.B.P.; Braga, I.A.; Valle, D. Insecticide resistance mechanisms of Brazilian Aedes aegypti populations from 2001 to 2004. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 77, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.P.; Paiva, M.H.; de Araujo, A.P.; Silva, E.V.; Silva, U.M.; Oliveira, L.N.; Santana, A.E.G.; Barbosa, C.N.; Neto, C.C.P.; Goulart, M.O.F.; et al. Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti populations from Ceará, Brazil. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazato, B.M.; Macoris, M.L.G.; Urbinatti, P.R.; Lima-Camara, T.N. Locomotor activity in Aedes aegypti with different insecticide resistance profiles. Rev. Saude Publica 2021, 55, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lenteren, J.C.; Bolckmans, K.; Köhl, J.; Ravensberg, W.J.; Urbaneja, A. Biological control using invertebrates and microorganisms: Plenty of new opportunities. BioControl 2018, 63, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becnel, J.J.; White, S.E.; Moser, B.A.; Fukuda, T.; Rotstein, M.J.; Undeen, A.H.; Cockburn, A. Epizootiology and transmission of a newly discovered baculovirus from the mosquitoes Culex nigripalpus and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; Paula, A.R.; Gomes, S.A.; Pedra, J.P.; Samuels, R.I. The potential of Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana isolates for the control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2009, 19, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setha, D.; Chantha, N.; Benjamin, S.; Socheat, D. Bacterial larvicide, Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis strain AM65-52 water dispersible granule formulation impacts both dengue vector Aedes aegypti (L.) population density and disease transmission in Cambodia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.; Tangudu, C.S.; Hurt, S.L.; Tumescheit, C.; Firth, A.E.; Garcia-Rejon, J.E.; Machain-Williams, C.; Blitvich, B.J. Discovery of a novel Tymoviridae-like virus in mosquitoes from Mexico. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruszynski, C.A.; Hribar, L.J.; Mickle, R.; Leal, A.L. A large scale biorational approach using Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (strain AM65-52) for managing Aedes aegypti populations to prevent dengue, chikungunya and Zika transmission. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A. Bacillus thuringiensis serovariety israelensis and Bacillus sphaericus for mosquito control. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2007, 23, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigott, C.R.; Ellar, D.J. Role of receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Dov, E. Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis and its mosquitocidal proteins. Toxins 2014, 6, 1222–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaki, Z.A.; Dom, N.C.; Alhothily, I.A. Efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis treatment on Aedes population using different applications at high-rise buildings. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, E.J.; Knols, B.G.; Takken, W. The potential of entomopathogenic fungi for mosquito control: A review. J. Insect Sci. 2004, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.A.; Paula, A.R.; Ribeiro, A.; Moraes, C.O.P.; Santos, J.W.A.B.; Silva, C.P.; Samuels, R.I. Neem oil increases the efficiency of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae for the control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imad-Silva, L.E.; Paula, A.R.; Ribeiro, A.; Butt, T.M.; Silva, C.P.; Samuels, R.I. A new method of deploying entomopathogenic fungi to control adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J. Appl. Entomol. 2017, 142, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, R.O.B.; Mallet, J.R.S.; Mesquita, E.; Gôlo, P.S.; Fiorotti, J.; Bittencourt, V.R.E.P.; Pontes, E.G.; Angelo, I.C. Larvicidal activity, route of interaction and ultrastructural changes in Aedes aegypti exposed to entomopathogenic fungi. Acta Trop. 2021, 213, 105732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, R.I.; Paula, A.R.; Carolino, A.T.; Gomes, S.A.; Morais, C.O.P.; Cypriano, M.B.C. Entomopathogenic organisms: Conceptual advances and real-world applications for mosquito biological control. Open Access Insect Physiol. 2016, 6, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, R.O.B.; de Sousa Queiroz, R.R.; Ribeiro, A.; Ribeiro, Y.R.d.S.; Boechat, M.S.B.; Carolino, A.T.; Santa-Catarina, C.; Samuels, R.I. Encapsulation of Beauveria bassiana conidia as a new strategy for the biological control of Aedes aegypti larvae. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 31894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley, A.K. Fungal pathogens of insects: Cuticle degrading enzymes and toxins. Adv. Bot. Res. 2003, 40, 241–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.M.; Coates, C.J.; Dubovskiy, I.M.; Ratcliffe, N.A. Entomopathogenic fungi: New insights into host-pathogen interactions. Adv. Genet. 2016, 94, 307–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.O.; Silva, H.H.G.; Luz, C. Effect of Metarhizium anisopliae isolated from soil samples of the central Brazilian Cerrado against Aedes aegypti larvae under laboratory conditions. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2004, 33, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, R.O.B.; Farias, F.S.; Freitas, M.C.; Balduino, C.J.R.; Mesquita, E.S.; Corval, A.R.C.; Golo, P.S.; Pontes, E.G.; Bittencourt, V.R.E.P.; Angelo, I.C. In vitro control of Aedes aegypti larvae using Beauveria bassiana. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 12, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolino, A.T.; Teodoro, T.B.P.; Gomes, S.A.; Silva, C.P.; Samuels, R.I. Production of conidia using different culture media modifies the virulence of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium against Aedes aegypti larvae. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2021, 58, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, T.; Middelman, A.; Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Takken, W.; Knols, B.G.L. Factors affecting fungus-induced larval mortality in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles stephensi. Malar. J. 2010, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolino, A.T.; Gomes, S.A.; Teodoro, T.B.P.; Mattoso, T.C.; Samuels, R.I. Aedes aegypti pupae are highly susceptible to infection by Metarhizium anisopliae blastospores. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, E.; Takken, W.; Knols, B.G. Infection of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae with the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae reduces blood feeding and fecundity. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006, 91, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnyone, L.L.; Kirby, M.J.; Mpingwa, M.W.; Lwetoijera, D.W.; Knols, B.G.; Takken, W.; Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Russell, T.L. Infection of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes with entomopathogenic fungi: Effect of host age and blood-feeding status. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, A.R.; Imad-Silva, L.E.; Ribeiro, A.; Silva, G.A.; Silva, C.P.; Butt, T.M. Metarhizium anisopliae blastospores are highly virulent to adult Aedes aegypti, an important arbovirus vector. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbro, J.M.; Johnson, P.H.; Thomas, M.B.; Ritchie, S.A.; Kay, B.H.; Ryan, P.A. Effects of Beauveria bassiana on survival, blood-feeding success, and fecundity of Aedes aegypti in laboratory and semi-field conditions. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanford, S.; Chan, B.H.K.; Jenkins, N.; Sim, D.; Turner, R.J.; Read, A.F.; Thomas, M.B. Fungal pathogen reduces potential for malaria transmission. Science 2005, 308, 1638–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, R.J.; Dillon, V.M. The gut bacteria of insects: Nonpathogenic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2004, 49, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N.A. The gut microbiota of insects: Diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, A.O.; Gusmão, D.S.; Santos, A.V.; Berbert-Molina, M.A.; Pimenta, P.F.P.; Lemos, F.J. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.). Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, C.; Moran, N.A. Molecular interactions between bacterial symbionts and their hosts. Cell 2006, 126, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakrishnan, L.; Sudhikumar, A.V.; Aneesh, E.M. Role of gut inhabitants on vectorial capacity of mosquitoes. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2018, 55, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Shi, P.; Li, J.; Niu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Wu, L.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; et al. A naturally isolated symbiotic bacterium suppresses flavivirus transmission by Aedes mosquitoes. Science 2024, 384, eadn9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.A.; Christophides, G.K. Immune interactions between mosquitoes and microbes during midgut colonization. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2024, 63, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Lai, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, H.; Li, F.; Wang, S. Insect pathogenic fungus interacts with the gut microbiota to accelerate mosquito mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5994–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.X.; Zhang, X.C.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Xia, Y.M.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, X.J. The interactions between gut microbiota and entomopathogenic fungi: A potential approach for biological control of Blattella germanica (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gichuhi, J.; Khamis, F.; Van den Berg, J.; Mohamed, S.; Ekesi, D.; Herren, J.K. Influence of inoculated gut bacteria on the development of Bactrocera dorsalis and on its susceptibility to the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, A.R.; Brito, E.S.; Pereira, C.R.; Carrera, M.P.; Samuels, R.I. Susceptibility of adult Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to infection by Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana: Prospects for dengue vector control. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2008, 18, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valência, M.D.; Miller, L.H.; Mazur, P. Permeability of intact and dechorionated eggs of the Anopheles mosquito to water vapor and liquid water: A comparison with Drosophila. Cryobiology 1996, 33, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forattini, O.P. Culicidologia Médica. 1º Edição; Edusp: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002; Volume 2, p. 864. ISBN 13: 9788531406997. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouache, K.; Raharimalala, F.N.; Raquin, V.; Tran-Van, V.; Raveloson, L.H.; Ravelonandro, P.; Maving, P. Bacterial diversity of field-caught mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, from different geographic regions of Madagascar. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 75, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Manfredini, F.; Dimopoulos, G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demko, A.M.; Patin, N.V.; Jensen, P.R. Microbial diversity in tropical marine sediments assessed using culture-dependent and culture-independent techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 6859–6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samuels, R.I.; Charnley, A.K.; Reynolds, S.E. The role of destruxins in the pathogenicity of three strains of Metarhizium anisopliae for the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. Mycopathologia 1998, 104, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcinskas, A.; Götz, P. Parasitic fungi and their interactions with the insect immune system. Adv. Parasitol. 1999, 43, 267–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, A.B.; Nascimento-Silva, M.C.L.; Talyuli, O.A.C.; Oliveira, J.H.M.; Pereira, L.O.R.; Oliveira, P.L.; Sorgine, M.H.F. Microbiota activates IMD pathway and limits Sindbis infection in Aedes aegypti. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Brayner, A.B.; Alves, L.C.; Dixit, R.; Barillas-Mury, C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science 2010, 329, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.M.; Maier, W.A.; Rottok, M.; Becker-Feldmann, H. Concomitant infections of Anopheles stephensi with Plasmodium berghei and Serratia marcescens: Additive detrimental effects. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A 1987, 266, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M.S.; Pumpuni, C.B.; Beier, J.C.; Davis, J.R. Effects of para-aminobenzoic acid, insulin, and gentamicin on Plasmodium falciparum development in anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1994, 31, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Z.; Ramirez, J.L.; Dimopoulos, G. The Aedes aegypti Toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusmão, D.S.; Santos, A.V.; Marini, D.C.; Bacci, M.; Berbert-Molina, M.A.; Lemos, F.J.A. Culture-dependent and culture-independent characterization of microorganisms associated with Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.) and dynamics of bacterial colonization in the midgut. Acta Trop. 2010, 115, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.D.S.; Campbell, J.A. The production of symbiont-free Glossina morsitans and an associated loss of female fertility. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 67, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogge, G. Sterility in tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans Westwood) caused by loss of symbionts. Experientia 1976, 32, 995–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Shi, W.; Zhen, Q.; et al. Engineered Metarhizium fungi produce longifolene to attract and kill mosquitoes. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 3075–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Bacterial Colonies (CFU) |

|---|---|

| S | 220 ± 2.86 a |

| S + Cb | 2 ± 0.55 b |

| S + Cb 3D | 9 ± 0.84 c |

| S + Cb 6D | 116 ± 2.17 d |

| S + Cb 9D | 218 ± 2 a |

| Conidial Concentration | Mean % Survival ± SD | S50 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 × 108 conidia mL−1 | 0 a | 2 |

| 1 × 107 conidia mL−1 | 0 a | 4 |

| 1 × 106 conidia mL−1 | 66.7 ± 1 b | NA |

| 1 × 105 conidia mL−1 | 87.8 ± 0.58 c | NA |

| 1 × 104 conidia mL−1 | 96.7 ± 0.1 d | NA |

| Control | 98.9 ± 0.58 d | NA |

| Treatments | Survival ± SD | S50 |

|---|---|---|

| S + Cb F | 38.9 ± 1.15 a | 7 |

| S F | 68.9 ± 0.58 b | NA |

| S + Cb C | 91.1 ± 1.15 c | NA |

| S C | 96.7 ± 1 c | NA |

| Time Zero | 3 Days | 6 Days | 9 Days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Survival (%) ±SD | Survival (%) ±SD | Survival (%) ±SD | Survival (%) ±SD |

| S + Cb F | 37.8 ± 1.15 aA | 38.8 ± 1.53 aA | 45.6 ± 1.53 aB | 58.9 ± 1.53 aC |

| S F | 65.5 ± 1.53 bA | 64.4 ± 0.58 bA | 63.3 ± 0.58 bA | 63.3 ± 1 aA |

| S + Cb C | 90 ± 0.2 cA | 91.1 ± 1.15 cA | 93.3 ± 0.1 cA | 96.7 ± 0.58 bB |

| S C | 98.9 ± 0.58 dA | 96.7 ± 1 cA | 96.7 ± 0.58 cA | 97.8 ± 0.58 bA |

| TREATMENTS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | S + Cb B F | S B F | S + Cb B C | S B C |

| Eggs | 532 ± 2.89 a | 824 ± 3.06 b | 981 ± 3,61 c | 1185 ± 6.24 d |

| Larvae | 255 ± 2.65 a (47.9%) | 556 ± 3.79 b (67.5%) | 943 ± 404 c (96,1%) | 1142 ± 9.61 c (96.4%) |

| Pupae | 134 ± 1.53 a (52.5%) | 427 ± 5.13 b (76.8%) | 934 ± 4.04 c (99%) | 1142 ± 9.61 c (100%) |

| Adults | 134 (100%) | 427 (100%) | 934 (100%) | 1142 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, J.P.; Paula, A.R.d.; Silva, L.E.I.; Silva, G.A.; Silva, C.P.; Butt, T.M.; Samuels, R.I. Antibiotic-Mediated Microbiota Depletion of Aedes aegypti Gut Bacteria Modulates Susceptibility to Entomopathogenic Fungal Infection and Modifies Developmental Factors. Parasitologia 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010004

Ribeiro JP, Paula ARd, Silva LEI, Silva GA, Silva CP, Butt TM, Samuels RI. Antibiotic-Mediated Microbiota Depletion of Aedes aegypti Gut Bacteria Modulates Susceptibility to Entomopathogenic Fungal Infection and Modifies Developmental Factors. Parasitologia. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Josiane Pessanha, Adriano Rodrigues de Paula, Leila Eid Imad Silva, Gerson Adriano Silva, Carlos Peres Silva, Tariq M. Butt, and Richard Ian Samuels. 2026. "Antibiotic-Mediated Microbiota Depletion of Aedes aegypti Gut Bacteria Modulates Susceptibility to Entomopathogenic Fungal Infection and Modifies Developmental Factors" Parasitologia 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010004

APA StyleRibeiro, J. P., Paula, A. R. d., Silva, L. E. I., Silva, G. A., Silva, C. P., Butt, T. M., & Samuels, R. I. (2026). Antibiotic-Mediated Microbiota Depletion of Aedes aegypti Gut Bacteria Modulates Susceptibility to Entomopathogenic Fungal Infection and Modifies Developmental Factors. Parasitologia, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia6010004