1. Introduction

In the mining industry, the main focus is on occupational safety and process quality. Particular attention is given to the most hazardous workplaces, such as tunnel surfaces. Frequent accidents and fatalities in tunnels [

1,

2,

3] highlight the need for automation in such environments. The primary goal should be to minimize human involvement in mining operations, with machines taking on a significant role in tasks such as excavation and material transport. The most widely used mining equipment in coal mines is the boom-type roadheader [

4,

5,

6]. Studies have demonstrated that using a boom-type roadheader increases the efficiency of fully mechanized mining, reduces labor costs and intensity, and improves working conditions for miners [

7,

8,

9]. Accordingly, there is a need to further improve the roadheader to ensure effective control under various operating conditions.

A significant research area concerns selecting the optimal cutting head rotation speed, depending on the mechanical properties of the rock. However, increasing the cutting head speed leads to excessive rock crushing, resulting in higher energy consumption, accelerated cutting blade wear, and increased vibration levels [

10,

11,

12]. Numerous studies [

13,

14,

15] have shown that rock strength and geological structure significantly influence mining efficiency. When selecting parameters, it is necessary to consider the machine’s operating environment, as well as parameters determined by the rotation speed and torque measured by the machine’s sensors.

The Geological Strength Index (GSI) is a comprehensive rock classification system that incorporates various geomechanical properties, including Hoek–Brown constants, deformation modulus, strength, and Poisson’s ratio. The system was developed using multiple methods to assess weak or strongly bonded rock masses. Determining these parameters is essential for the effective design of tunnels, caverns, and other engineering structures.

In [

16], the authors developed a robust controller for electrohydraulic position servo systems, using a roadheader cutting mechanism model and a high-gain disturbance observer verified through Lyapunov theory. They applied a backstepping-based sliding mode controller with saturation to reduce chattering, enhanced the Eel-Foraging optimization algorithm for tuning, and validated the controller via simulation and experiment. Separately, ref. [

17] proposed an intelligent joint cutting strategy combining LSTM deep learning with fuzzy inference control to improve energy efficiency by accurately identifying load conditions and adaptively adjusting cutting parameters. An adaptive cutting trajectory planning method for axial robotic roadheaders was developed using ant colony optimization to overcome the limitations of conventional spiral or reciprocating patterns in variable geological conditions. The method employs machine vision to detect fractures on the tunnel face, generates a grid map, and extracts fracture parameters (number, length, width, density) for each cell. These parameters are fed into a Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) to estimate the Geological Strength Index (GSI), which then guides an improved ant colony optimization algorithm in determining optimal cutting paths. Testing demonstrated that this approach reduces energy consumption, increases cutting efficiency, extends equipment lifespan, and enhances the overall intelligence of coal-mining robots [

18].

Previous studies have demonstrated that effective roadheader control strategies should prioritize optimizing energy efficiency while maintaining stable operation and rapid response. These findings lay the groundwork for the further development of advanced, energy-efficient control systems for mining machinery.

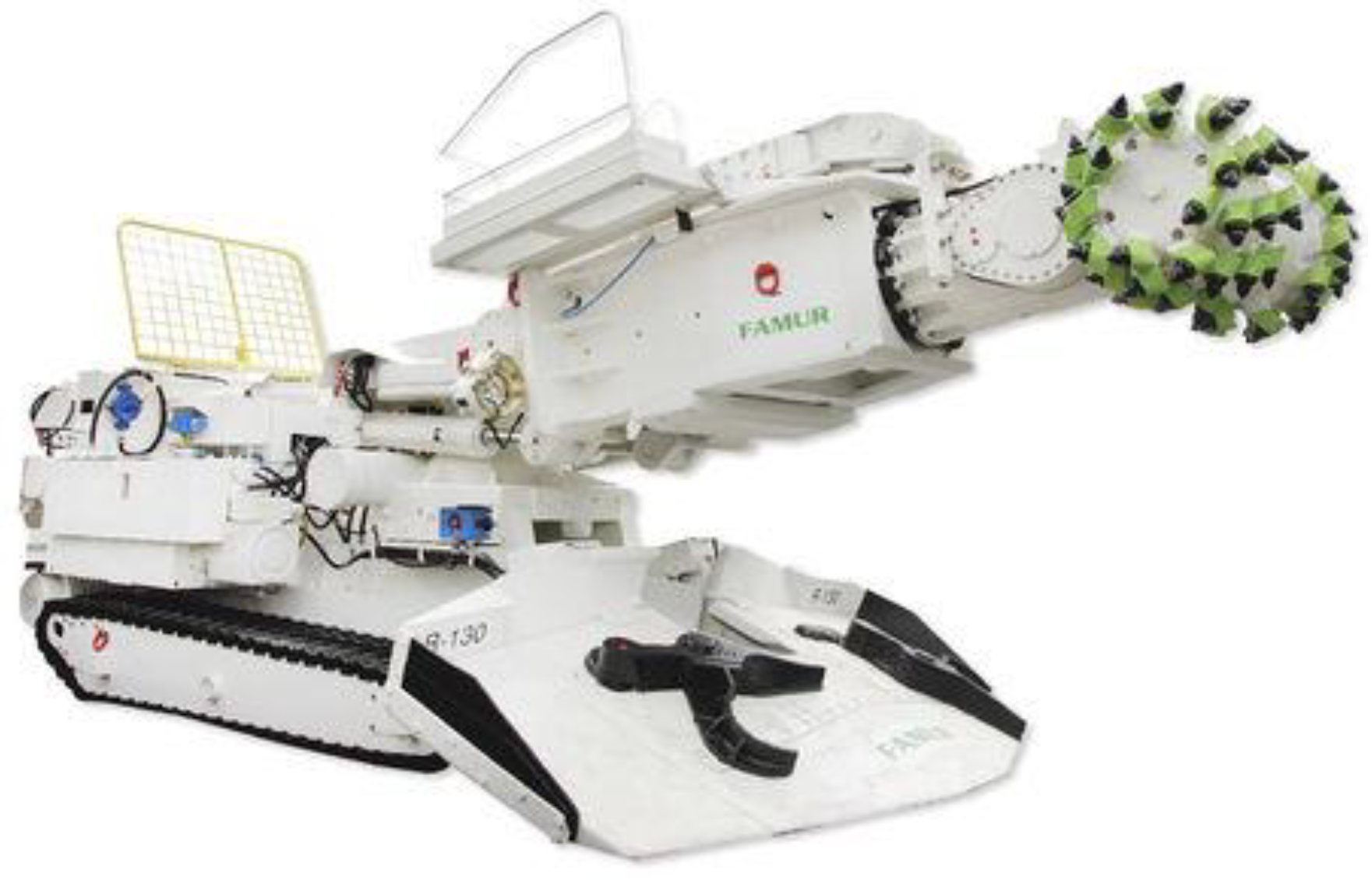

2. Roadheader Control Strategy

The control strategies employed by the roadheader should seek to maximize the energy efficiency of the mining process while also ensuring stable operation and a fast response time. Consequently, the ability of the cutting head to complete the task within the specified time must be balanced with its stability on the desired trajectory and its energy consumption. Various studies [

19,

20,

21] describe the concept of a cutting head speed control system and present the results of research conducted on a laboratory test bench equipped with a special R-130 roadheader with an inverter drive for the cutting head (

Figure 1). Closed-loop speed control is achieved using a PI controller. Various input signals—torque, speed, and current—are processed through the control unit, representing the entire control system as three cascaded feedback loops.

Accordingly, this work obtained optimal settings by simulating the electric drive system in the circuit. This represents the ITAE (Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error), which is the time integral multiplied by the absolute value of the error criterion.

The integral is computed as a discrete sum. Discrete Calculation (for simulations/data):

A distinctive feature of drive controllers calibrated according to the ITAE criterion is that the parameters are typically adjusted during fine tuning, resulting in a relatively short settling time. In addition, overshoot is quite modest, as shown in [

22,

23,

24].

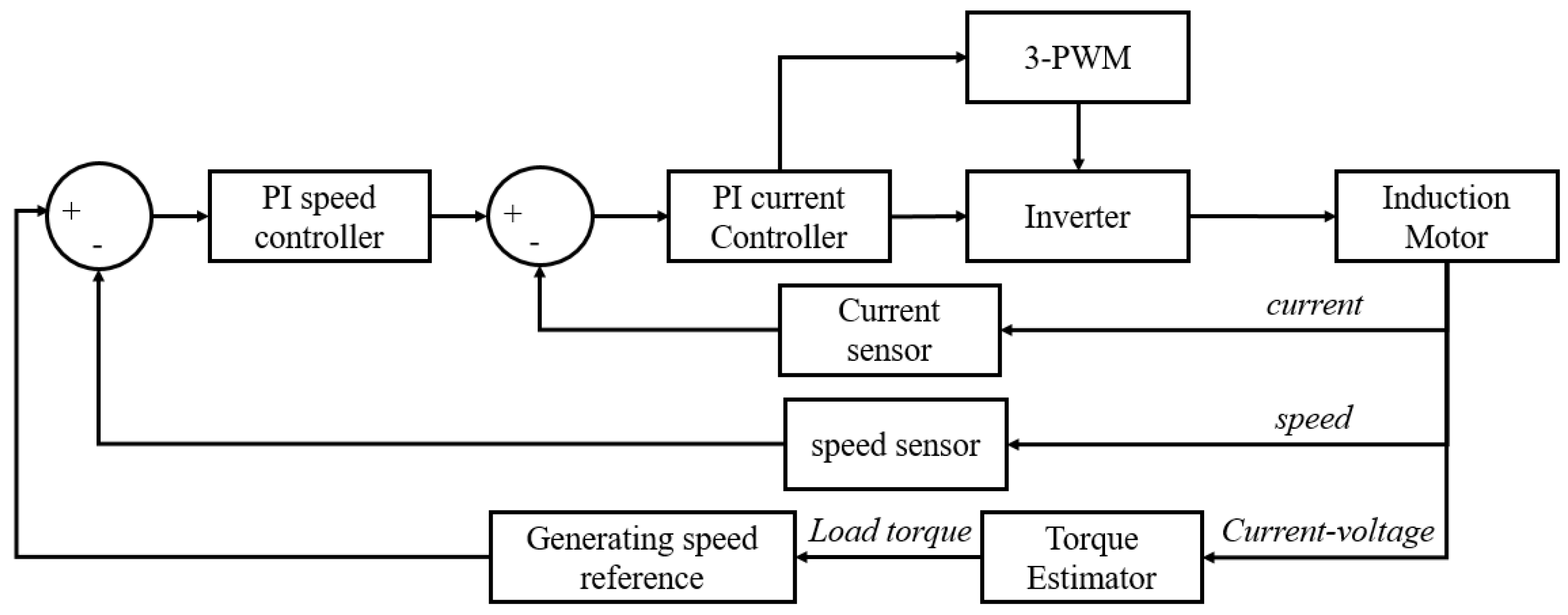

Figure 2 shows a complex control diagram consisting of two internal control loops: speed and current.

Laboratory experiments have shown that the developed control system, when combined with optimized controller parameters, ensures stability across a wide range of operating conditions [

25,

26]. The dynamic load on the cutting head drive, which is an indicator of the dynamic load on the roadheader, can be classified into one of five categories: overload, underload, nominal load, dynamic overload and low energy consumption. Consequently, the cutting process parameters are selected to achieve the useful load. The main characteristics of the automatic control method for cutting process parameters are given below [

27,

28].

Cutting width z [mm]—formed as a result of the displacement of the roadheader towards the cutting face (

Figure 3).

Cutting height h [mm] is understood as the height of the cut layer.

Angular velocity of the cutting heads [rad/s].

Cutting head travel speed vow [mm/s].

Figure 3.

Parameters of the cutting process using the boom roadheader.

Figure 3.

Parameters of the cutting process using the boom roadheader.

Recent studies have demonstrated the significant advantages of automating the cutting heads of roadheaders [

29]. The results showed that the developed control algorithm increased cutting efficiency considerably compared to manual control. This improvement was due to the optimization of the roadheader’s dynamic load, leading to a substantial reduction in energy consumption during the cutting process. Cutting efficiency in automatic mode was found to be three times higher than in manual mode, with energy consumption for cutting reduced by 50%. The study demonstrated that effectively controlling process parameters, combined with adjustable changes in the angular velocity of the cutting heads, contributes to achieving high cutting speeds on the workpiece surface while minimizing the duration of excessive dynamic loads.

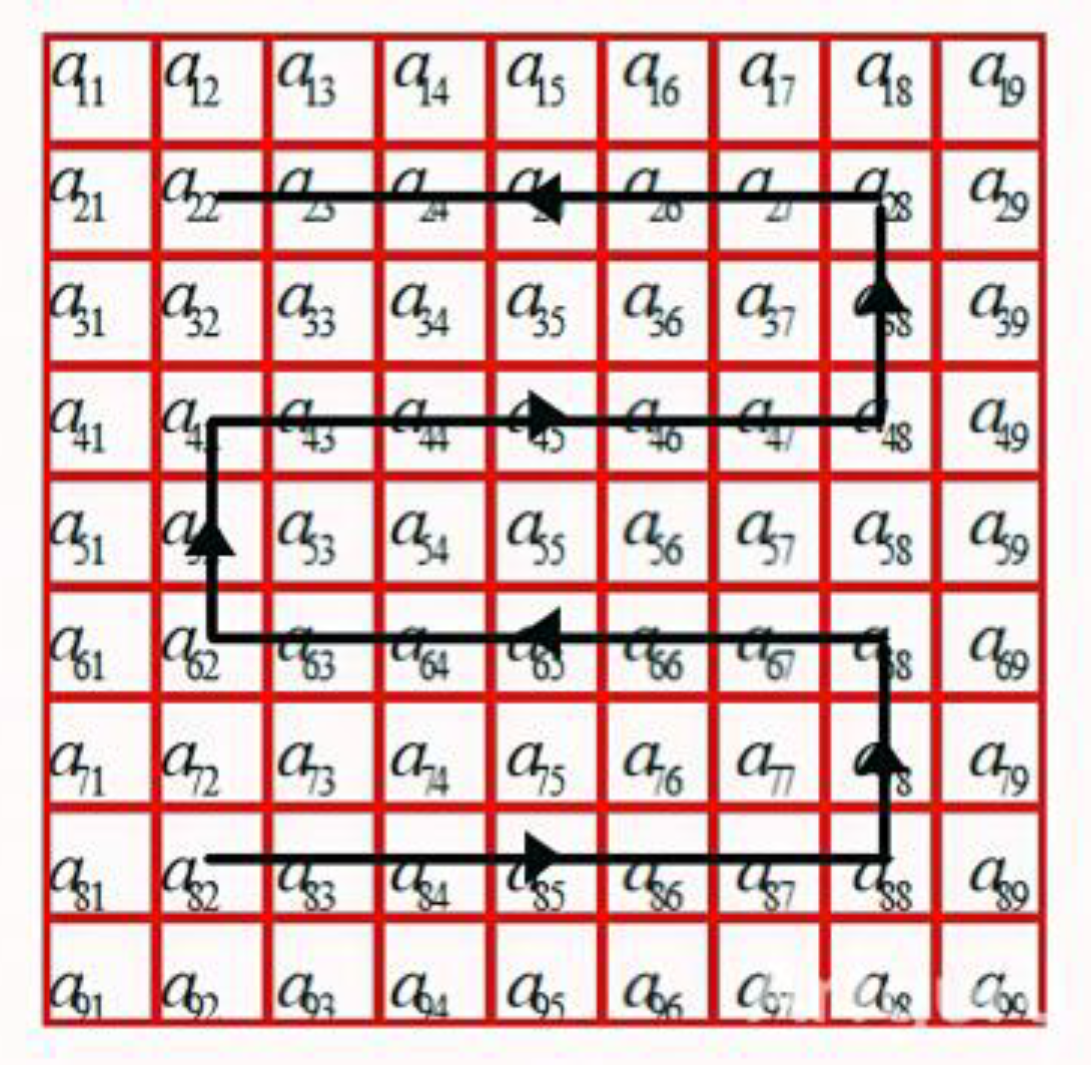

Dong et al. [

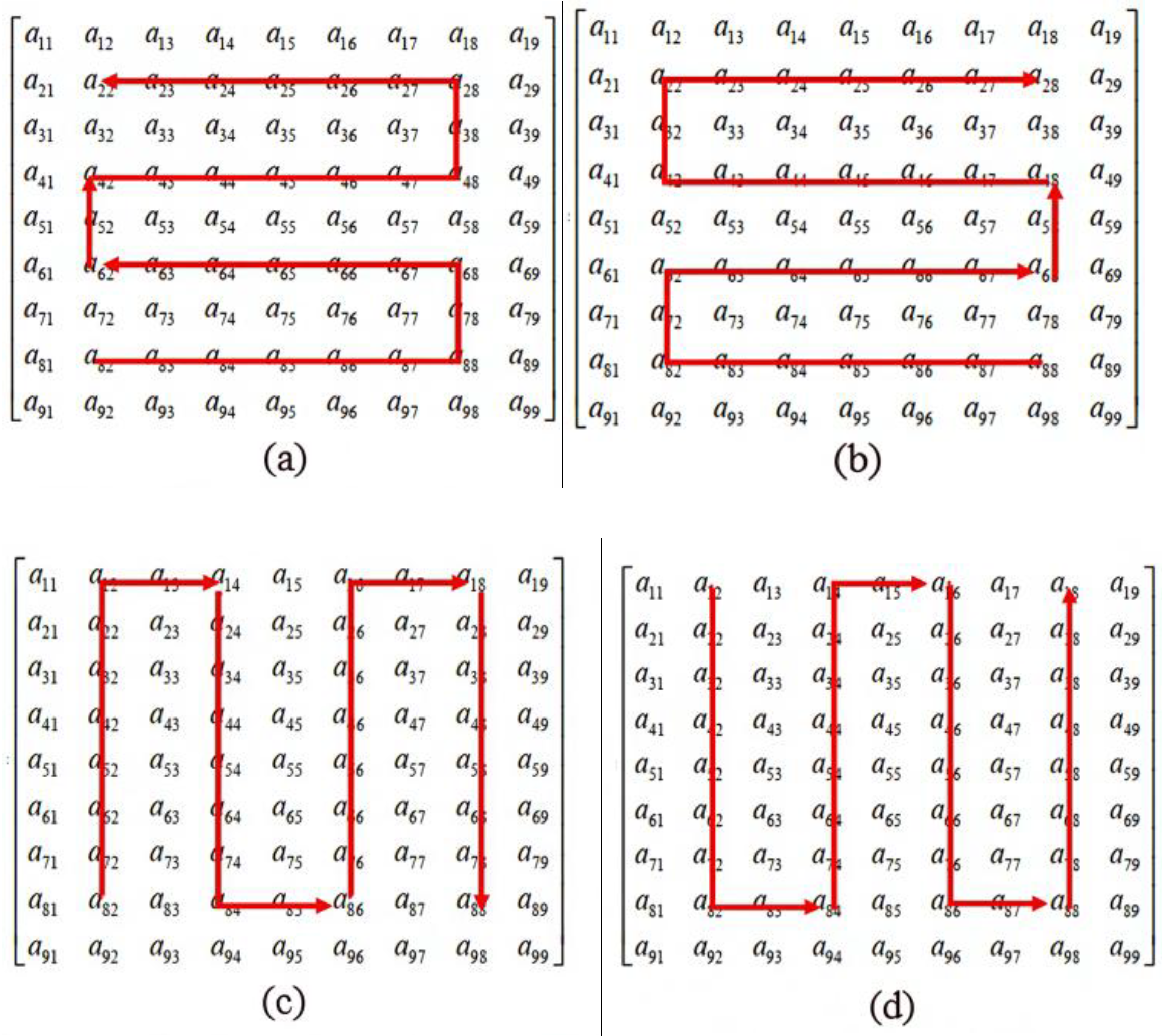

18] proposed an image-processing method to detect seam characteristics in palisade cracks, presenting a quantitative model of the Geological Strength Index (GSI). Fractal dimension was used to determine the GSI distribution in the coal seam, and the roadheader’s cutting head was automatically adjusted to set the speed. This concept determines geological strength in order to overcome the limitations of a constant cutting head speed and allows the speed to be adaptively adjusted according to the strength of the coal and rock. In this application, the GSI is based on image processing using 1 m × 1 m images. First, the image is divided into 81 squares in a 9 × 9 matrix. Then, a series of image-processing operations are performed, including edge detection, binarization, noise removal, structure merging, and other steps. After processing, cracks and edges become clearly visible, and rock hardness is determined from the width and length of the cracks.

Once the GSI coefficient has been determined, the reference speed is set according to the degree of hardness, i.e., depending on the coefficient value. A high coefficient value indicates greater hardness. It is important to select the cutting head trajectory based on geological data and to ensure that both the cutting head speed and the trajectory are adaptive to the environment. The traditional cutting trajectories used for axial robotic roadheaders (spiral or reciprocating) are too simple to meet the requirements of adaptive planning. Planning the cutting trajectory of an axial robotic roadheader using ant colony optimization enables the machine to automatically adapt to the rock characteristics of the tunnel face. This addresses the problems of high energy consumption and low cutting efficiency in existing methods [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

The following (

Figure 4) shows how the image was divided into 99 parts, and the trajectory of the cutting head was determined in the shape of the letter S.

To improve results and achieve maximum efficiency and energy savings, based on research findings.

We can choose the best path based on the sum of GSI values. There are several options for where the path of the letter ‘S’ begins:

From left to right.

From right to left.

From bottom to top.

From top to bottom.

Then we take the smaller sum, which corresponds to a lower speed and therefore lower energy consumption. These four paths are shown in

Figure 5.

Accurately determining the Geological Strength Index (GSI) under poor lighting and environmental conditions remains a key challenge. To address this, the DIS-Mine algorithm was developed to enhance image quality in low-visibility settings, effectively reducing noise, distortion, and contrast loss while outperforming existing methods [

33]. Further advancements in image optimization have integrated traditional image signal processing (ISP) with convolutional neural networks, improving metrics such as PSNR by 2.9–4.9%, SSIM by 4.3–11.4%, and VIF by 4.9–17.8% compared to state-of-the-art approaches, enabling real-time enhancement in simulated mining environments [

34].

In parallel, robust speed control of three-phase motors under disturbances and sudden loads is critical. Integral Sliding Mode Control (ISMC) has been shown to achieve faster convergence and eliminate steady-state error compared to conventional SMC, offering improved robustness [

35]. While studies vary based on sliding surface design, the overarching aim is to identify control laws that optimize response and performance under nonlinear conditions [

36].

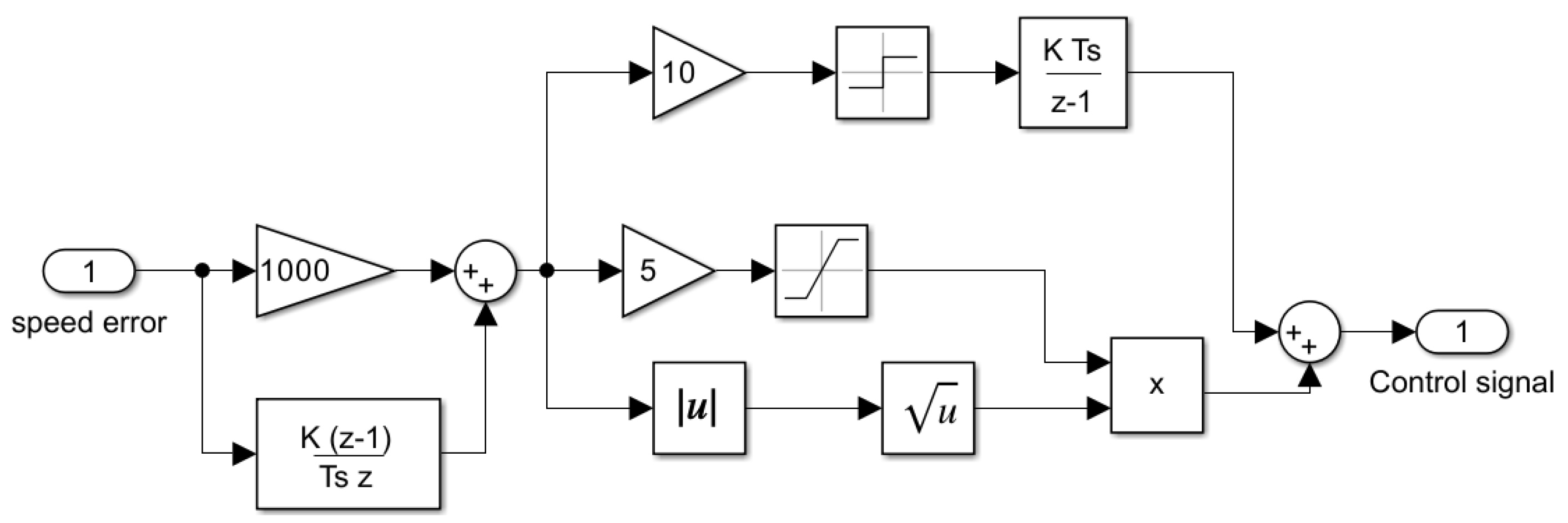

Building on these foundations, this article implements Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Control (STSMC) within a Field-Oriented Control (FOC) framework for the speed loop, with parameters tuned to achieve optimal performance in comparison to the traditional PI controller.

3. Implementation of Super-Twisting SMC and PI for Speed Loop Controller in FOC-Based Asynchronous Motors

The speed loop design of an asynchronous motor can be implemented using several strategies. The classic case of an asynchronous induction motor includes a PI controller; however, this method has limitations when it comes to overcoming disturbances and sudden loads. Nonlinear controllers, especially sliding mode control (SMC), are highly effective in overcoming disturbances. There are many control laws that can be applied in SMC, but the sensitivity of the system and the nature of the environment make the choice of control law more challenging. Super-twisted sliding mode control (STSMC) is a powerful and highly efficient method of overcoming nonlinear phenomena. The selection and application of the control law to our control object, and its comparison with the PI controller in different operating conditions, are important.

3.1. Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Control (STSMC)

Sliding mode control is a robust nonlinear control method that drives the system state to a predefined sliding surface and maintains it there despite uncertainties or disturbances.

Sliding mode control is a robust control method that can overcome disturbances and the inaccuracy of the mathematical model. It is characterized by its ability to overcome nonlinearity, uncertainty, and unknown disturbances. The sliding surface for the speed loop is given by the following equation:

where

Here,

is the current speed,

is the desired speed, and

is a positive constant. The control equation is as follows:

where

and

are positive constants. A trial-and-error method was used to achieve the desired speed response.

The finite-time reaching (convergence) property of the Super-Twisted Algorithm (STA)/STSMC and related proof techniques (Lyapunov/homogeneity proofs, reaching-time estimates, gain design).

To guarantee the finite-time stability of the proposed Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Controller (STSMC), two standard assumptions are imposed. First, the time derivative of the lumped disturbance acting on the speed dynamics—comprising load torque variations and model uncertainties—is bounded, i.e., ; this is physically justified as mechanical loads cannot change with an arbitrarily high rate. Second, the sliding variable dynamics can be expressed in the canonical form , where the control coefficient is bounded and strictly positive, satisfying . Under these assumptions, finite-time convergence is established using the Lyapunov function , and representing the internal state of the integral term and disturbance. The time derivative of V satisfies the inequality for some , provided the controller gains and are selected to fulfill the sufficient conditions dependent on and . This proof rigorously ensures the sliding variable converges to zero in finite time, thereby guaranteeing the robustness and dynamic performance of the induction motor speed control system.

3.2. PI Controller

A PI controller is an inexpensive and reliable way to control the speed of an asynchronous motor [

35]. It works by achieving a minimum tracking error between the setpoint and the actual value by applying proportional and integral actions to the controller gain on the motor speed when the load torque changes. The optimal gain coefficient settings (

and

) are then selected to balance sensitivity, stability and accuracy, and to obtain the desired value

The PI controller generates a control signal u(t) based on the speed error:

where

: Proportional gain coefficient.

: Integral gain coefficient.

: Speed error at time t.

: Integral of speed error over time.

The control equation can be written in discrete form as follows, depending on the method of direct Euler transformation to obtain the PI(z) controller used:

Then,

Sampling time s.

In induction motor drives, PI controllers adjust the inverter’s frequency and voltage to maintain the required motor speed under various load conditions. PI controllers are highly effective in situations involving dynamic load changes, such as sudden torque variations in mining and conveyor systems, where stringent speed variation requirements are in place.

3.3. Parameter Tuning Methodology

This study employed a multi-criteria approach to evaluate and optimize controller performance. Key transient response metrics were monitored during the tuning process, with the following design targets: a maximum settling time (within ±2% of the final value) of 0.5 s to ensure rapid stabilization, a maximum percent overshoot of 20% to limit mechanical stress and vibrations. Additionally, steady-state error was minimized to below 0.5 RPM to guarantee long-term tracking precision essential for accurate cutting head positioning. Controller parameters were iteratively adjusted to achieve a balanced performance across all these criteria, with the ITAE value serving as the primary quantitative objective function for optimization.

Controller parameters for both STSMC and PI controllers were systematically tuned to minimize the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) performance criterion. The tuning process involved iteratively adjusting parameters within specified ranges:

STSMC: [1–20], [500–2000], [2–20].

PI: [500–5000], [500–5000].

Parameters were evaluated under standardized test conditions (100 N·m load, 5-s simulation window) until the ITAE value was minimized ensuring optimal tracking performance with minimal overshoot and fast settling.

3.4. Technical Specifications

The technical specifications of the induction motor used in the model are given in

Table 1 below.

The desired modeling speed corresponds to the values in the table below, since the motor operates at low speeds of 20 to 50 RPM.

Table 2 shows the different GSI calculation speeds.

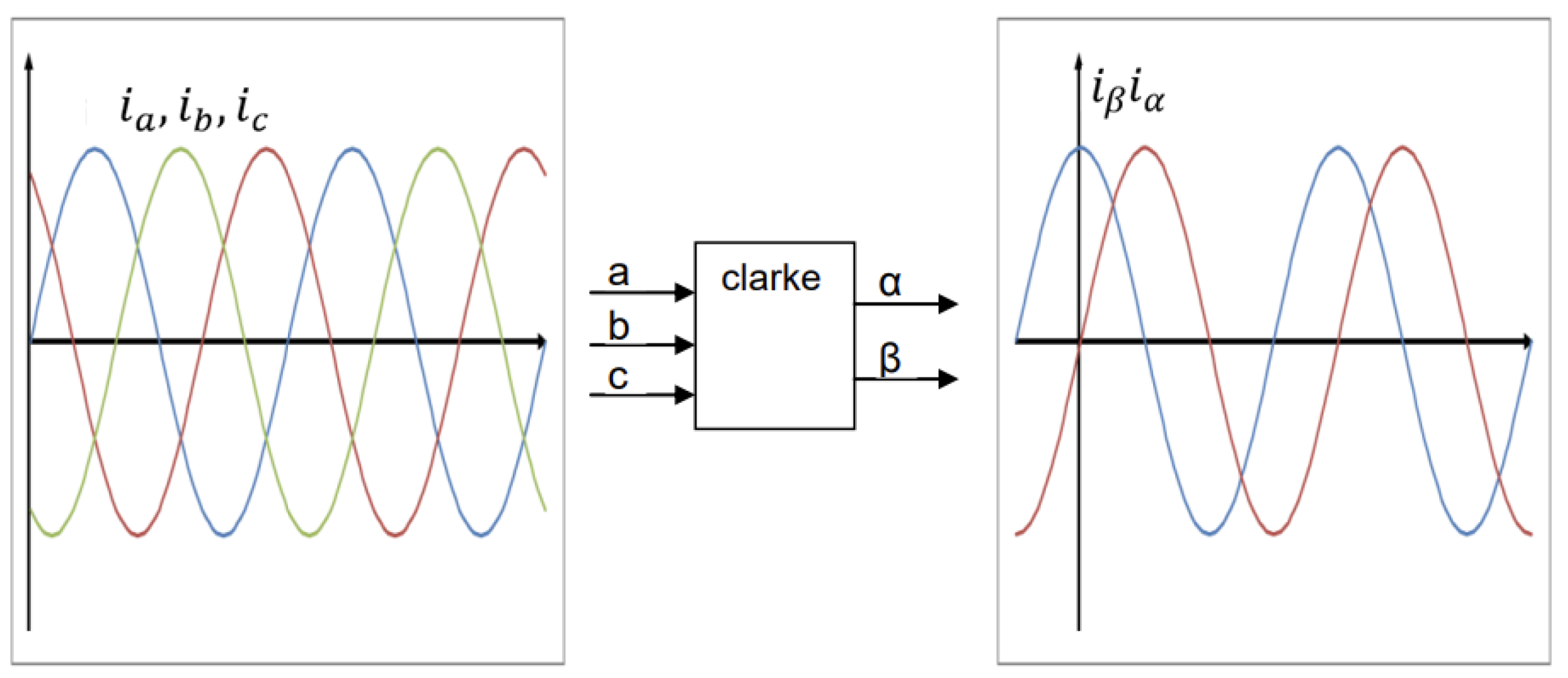

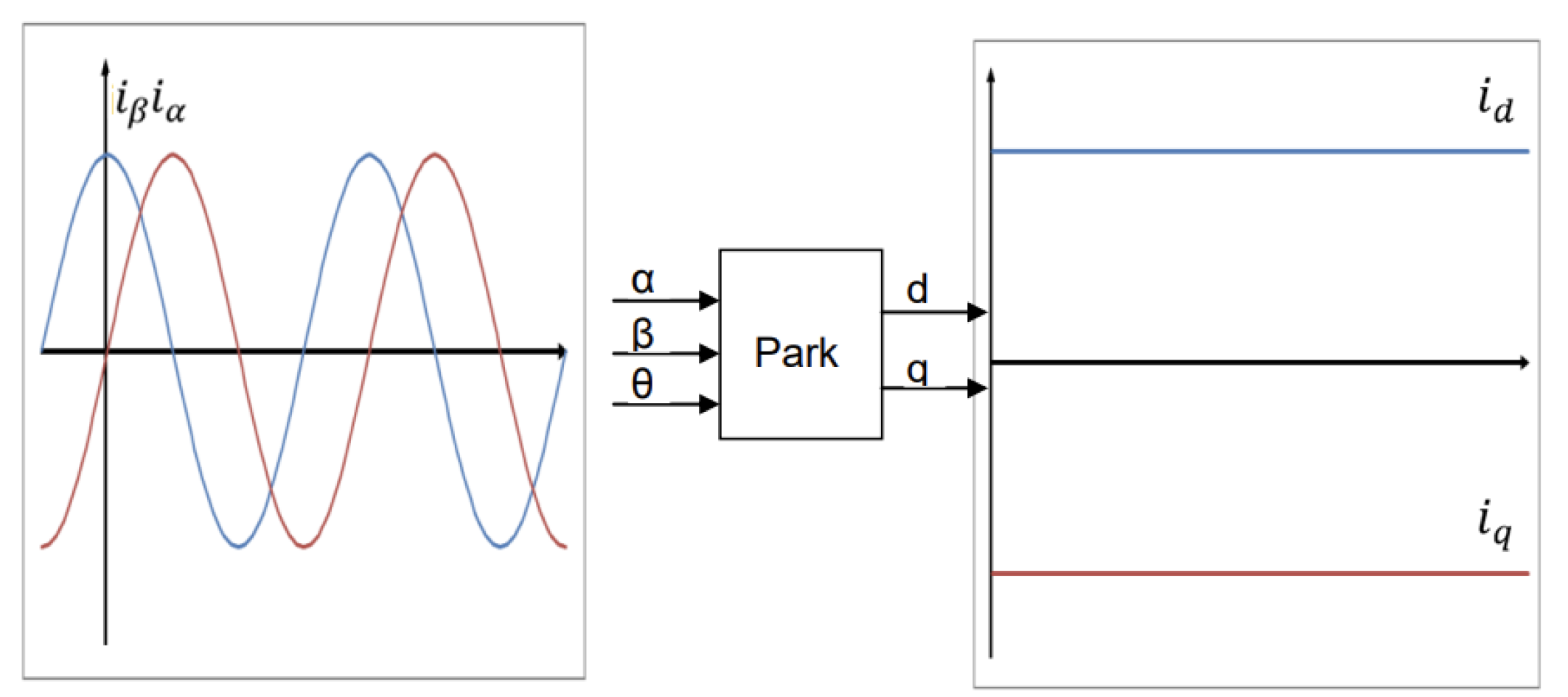

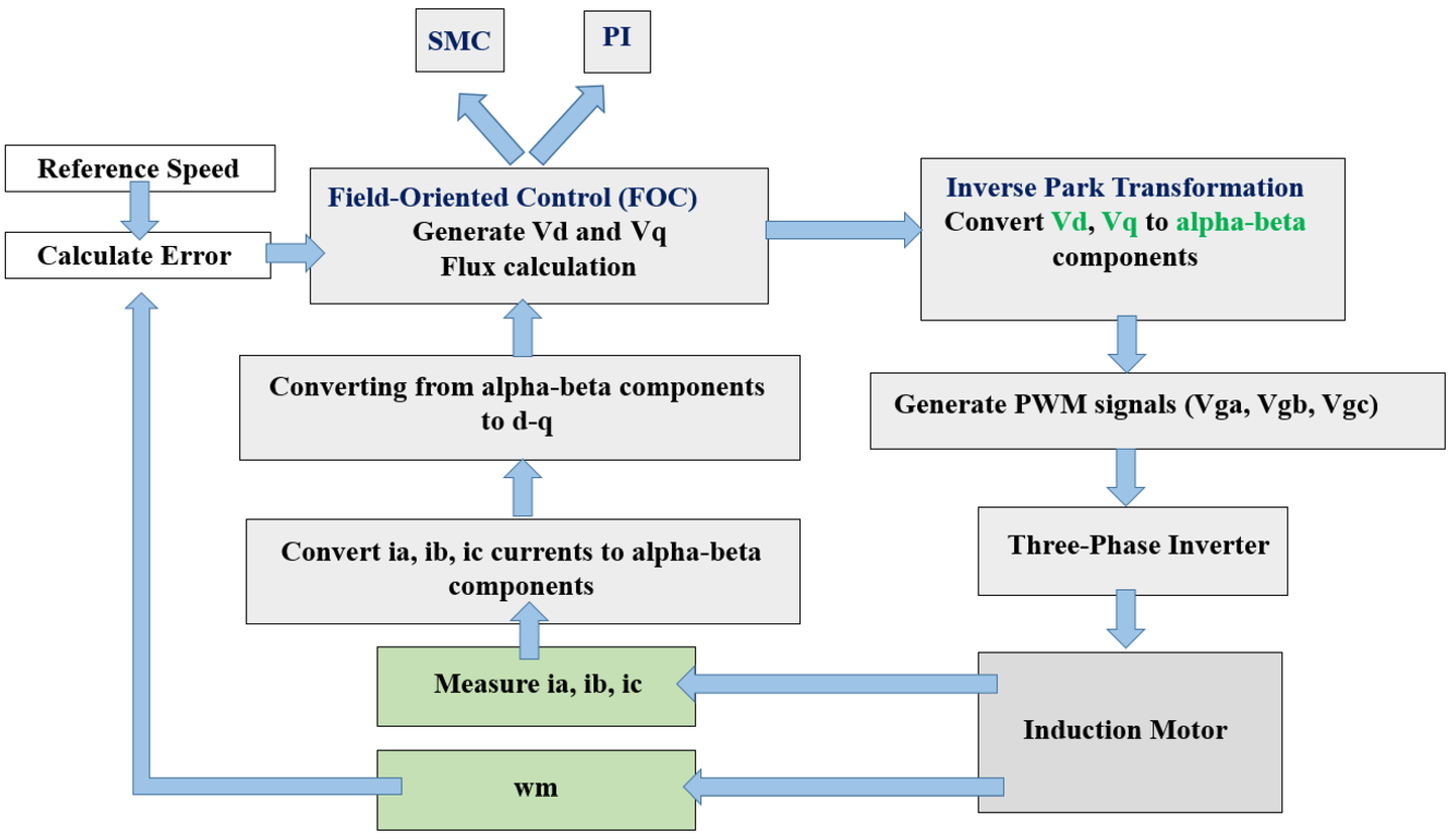

4. Speed Loop Control of an Asynchronous Motor Using Field-Oriented Control (FOC)

Field-oriented control (FOC) is a well-known method of achieving high-precision speed control of an asynchronous motor. It allows independent control of torque and flux, providing a similar performance to that of a DC motor. This improves efficiency in both dynamic and steady-state modes. The principle of FOC involves converting the three-phase currents in the stator into a rotating d-q axis system via the Clarke transformation (see

Figure 6).

where

: the instantaneous currents of the three-phase electrical system.

Figure 6.

Clark transformation.

Figure 6.

Clark transformation.

After applying Park transformations (

Figure 7).

After performing the transformation of currents and obtaining the currents, they can be entered into the algorithm execution block to generate control signals.

The following (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) shows the internal diagram of the FOC method for generating control signals (

d-axis voltage, q-axis voltage, and electrical angle)

by using PI and STSMC.

The simulation equations for obtaining control signals are given below:

Calculation of the reference value

:

where

is the desired rotor flux:

Calculation of the rotor magnetic flux:

where

is the rotor time constant:

Using the Forward Euler method

We obtain the following equation:

Calculation of the reference value

and electromagnetic moment

:

Calculation of the electric angle of the flux (electric angle):

Rotor rotation speed:

—mechanical speed of the rotor (rad/s).

Park’s inverse transformation:

The signals are fed into the inverter’s PWM signal calculation unit for motor control.

In field-oriented control (FOC), the d-q axis system independently regulates rotor flux along the d-axis and torque along the q-axis. Implementation involves measuring the three-phase motor currents and transforming them into the d-q reference frame. The d-axis current is controlled to maintain the desired rotor flux, while the q-axis current is adjusted to regulate torque. Motor speed is controlled via a PI controller that modulates the torque-generating current. The resulting d-q signals are filtered, inverse-transformed back to three-phase quantities, and used to generate pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals for the inverter [

31]. FOC offers high dynamic response, improved efficiency, minimal torque ripple, and effective control across a wide speed range—including low and zero speeds. These attributes make it suitable for applications such as electric vehicles, CNC machines, conveyors, robotics, and wind turbines.

Figure 10 shows a model of an asynchronous motor. This Simulink model illustrates the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) implementation for an asynchronous motor (IM). FOC, also known as vector control, is a widely used control strategy for achieving highly efficient control of AC induction motors. This strategy separates the torque and flux components of the motor, causing it to act as a separately excited DC motor.

The model in MATLAB/Simulink 2023b is represented by a set of blocks, each of which classifies it as an induction motor equipped with an efficient control system. The command input block provides the desired rotor speed . The actual rotor speed is subtracted from it; the difference is then processed in the FOC block. The input elements of the block are the stator current components and and the rotor speed . The block calculates the necessary stator voltage components in the d_q frame to provide effective torque and flux control without decoupling.

The components are converted to α-β components using a Park inverse transformation block, which forms the basis of space vector PWM. This input feeds a signal to the SVPWM block, which converts it into six PWM voltage signals () that control the three-phase inverter. Now the 780 V DC voltage is converted into a three-phase AC voltage that powers a 50 HP, 460 V induction motor, generating output signals such as stator currents (), rotor speed and electromagnetic torque .

To ensure correct feedback, the Forward Clark conversion block converts the α-β components back to components. This block is designed to correctly track the motor’s operation. The phase and line voltage control block measures and sends data on the voltage supplied to the motor for analysis. Finally, the constant torque load unit applies a constant mechanical torque to the motor, approximating the actual load applied to it for performance evaluation.

This model (

Figure 10) is an asynchronous motor drive with vector control, which is based on field-oriented control using PI and STSMC with space vector PWM. High motor control performance and smooth operation can only be achieved by ensuring accurate torque-speed control.

5. Results

FOC-PI and FOC-STSMC were applied. The control object was a three-phase induction motor operating under different conditions to simulate working conditions in mines. The two methods were first compared in ideal conditions, then in the presence of noise on the measured speed signal from the sensor, and finally under sudden or variable load in the form of a ramp. The power consumption of the engine under load was also compared when using a variable speed according to GSI or a constant speed.

The controller parameters were selected manually using the FOC method (tuning error-trial method) until the best response was obtained, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4:

The simulation tests conducted in this study—including step response, rejection of white noise, and response to sudden and ramp loads—were specifically designed to replicate the challenging operational conditions of a roadheader in a coal mining environment. The step response evaluates the machine’s ability to quickly and smoothly transition between different rock hardness layers, as determined by the GSI-based speed strategy. The sudden load application simulates the impact when the cutting head encounters a hard inclusion or a pocket of very dense material. The ramp load test represents the gradual increase in resistance experienced when the cutting head engages more deeply into the coal seam or when moves from a soft to a harder stratum. Finally, the injection of measurement noise directly models the real-world sensor inaccuracies caused by EMI, vibration, and dust in an underground mine. Therefore, the superior performance of the FOC-STSMC controller in these tests, particularly in handling transient loads, demonstrates its strong potential to enhance cutting efficiency, reduce equipment wear, and ensure stable operation in real mining scenarios.

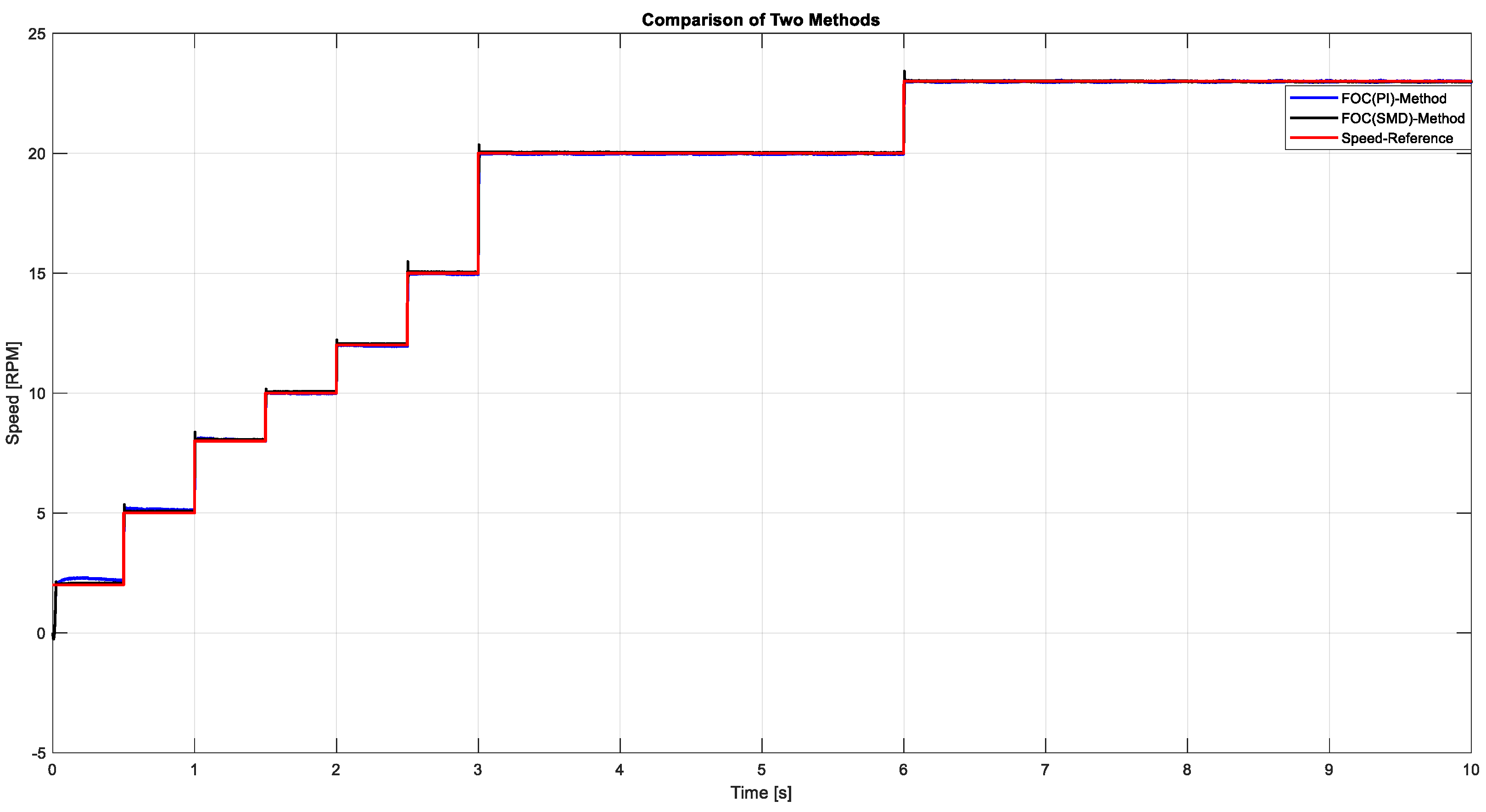

Figure 11 shows the motor’s controlled acceleration to 23 RPM via incremental steps. Both controllers achieved stable responses, with FOC-STSMC demonstrating tighter tracking at each step.

Figure 12 provides a detailed visualization of the dynamic speed transition of the roadheader’s induction motor to 30 RPM under two control schemes: Field-Oriented Control with a Proportional-Integral (FOC-PI) controller and Field-Oriented Control with Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Control (FOC-STSMC). The figure highlights the superior transient and steady-state performance of the FOC-STSMC controller, which achieves a faster settling time, a lower steady-state error, and reduced overshoot (less than 17%) compared to the conventional FOC-PI approach. While PI controllers are often favored for their simplicity and stability in low-speed, undisturbed environments, their performance deteriorates significantly under external disturbances and load variations—conditions that are common in real mining operations. In contrast, the FOC-STSMC not only maintains tighter speed regulation but also demonstrates enhanced robustness and disturbance rejection due to its nonlinear control structure, which actively compensates for model uncertainties and sudden load changes. The figure thus serves as empirical evidence that the advanced STSMC algorithm offers a more reliable and responsive control solution for roadheader operation, particularly in the challenging and variable geological conditions encountered in underground coal mining.

The quantitative performance comparison between (FOC-PI) and (FOC-STSMC) is summarized in

Table 5. Key metrics include settling time, percentage overshoot, and steady-state error.

To provide quantitative performance metrics, the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) was calculated over a 5-s simulation window. As shown in

Table 6, the FOC-STSMC controller demonstrates significantly lower accumulated error across both no-load and loaded conditions. The result demonstrates that the FOC-STSMC controller improves tracking performance by 43% compared to the standard FOC-PI under no-load conditions., while the 15.15% improvement under 100 N·m load demonstrates enhanced robustness to disturbances.

In the harsh and complex environment of an underground coal mine, the accuracy of the roadheader’s engine speed measurements is critically compromised by a confluence of factors. Dense dust clouds from cutting operations can obscure optical encoders, while persistent, high-amplitude mechanical vibrations from the cutting head and other machinery induce significant jitter in sensor readings. Furthermore, confined tunnels act as a conduit for intense electromagnetic interference (EMI) from high-power Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) and adjacent motors, corrupting signal integrity. The composite effect of these independent disturbances—dust, vibration, and EMI—manifests as high-frequency noise and random fluctuations in the speed feedback signal. To rigorously test the controller’s robustness, these real-world perturbations were modeled as additive white Gaussian noise with an amplitude of ±0.01 RPM. The Gaussian distribution was selected because the cumulative impact of numerous independent random disturbances tends toward a normal distribution, as dictated by the Central Limit Theorem. The amplitude was justified based on the performance of industrial-grade encoders; relative to a typical operating speed of 30 RPM, it creates a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 3000:1. This represents a conservative and realistic level of signal degradation, ensuring the control system is validated against a challenging yet plausible noise profile.

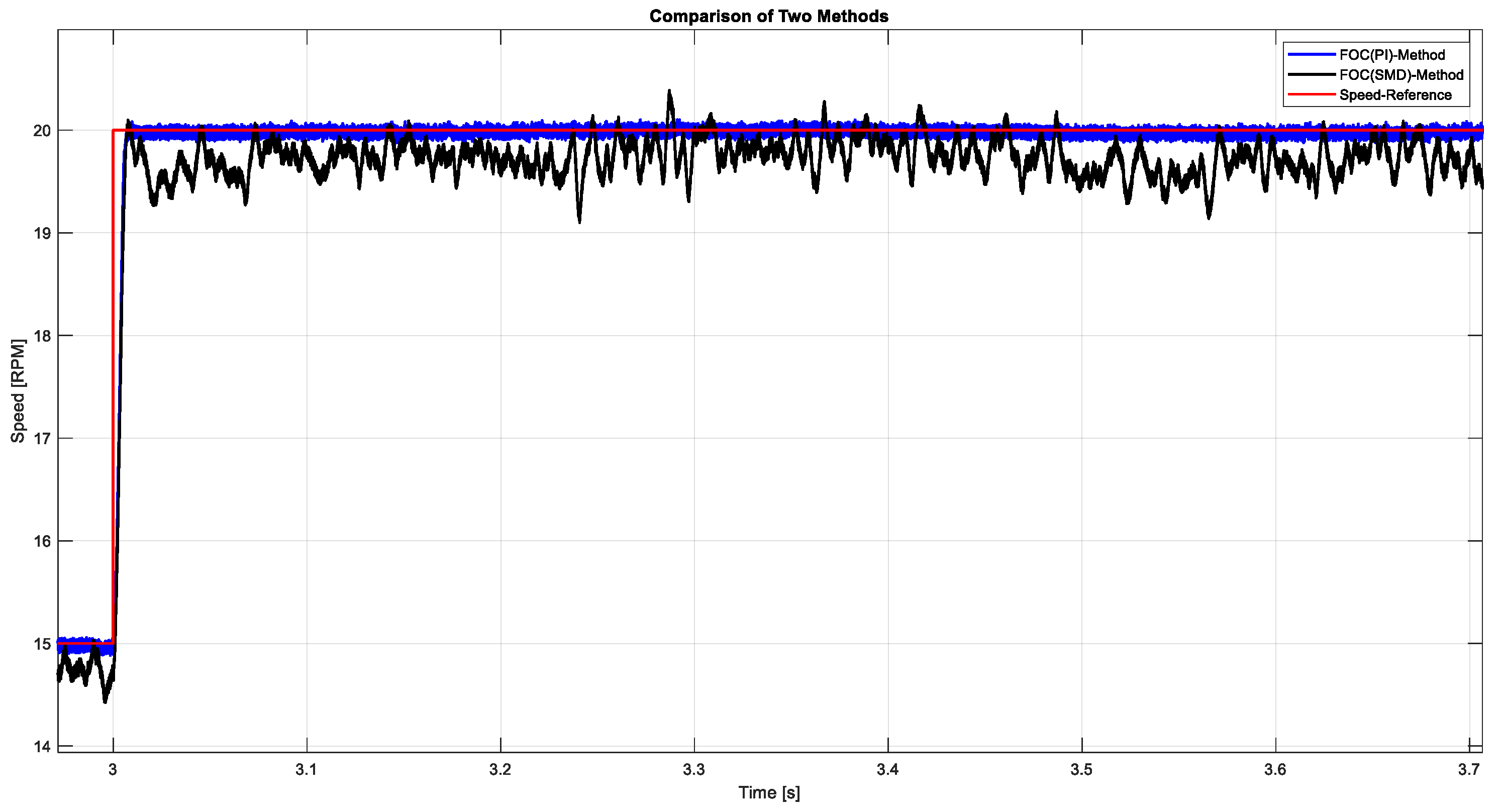

Figure 13 illustrates the impact of simulated measurement noise—representing real-world disturbances such as electromagnetic interference, vibration, and dust—on the motor’s speed feedback signal under FOC-PI and FOC-STSMC. The injected noise exhibits rapid fluctuations and contains high-frequency components, conditions under which the Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Controller (STSMC) demonstrates its inherent sensitivity. This sensitivity arises from the discontinuous signum (SGN) function within the STSMC algorithm, which can induce high-frequency chattering in the control signal when exposed to noise. In contrast, the PI controller exhibits a natural low-pass filtering effect, effectively attenuating the high-frequency noise and resulting in a smoother, more stable speed response. This suggests that while STSMC offers superior disturbance rejection in terms of load variations, its performance in noisy signal environments may require additional filtering or signal conditioning to mitigate chattering. Thus,

Figure 13 underscores a key trade-off in controller selection: robustness to mechanical disturbances versus susceptibility to measurement noise, highlighting the practical need for integrated sensor fusion or advanced filtering strategies in mining applications.

Data processing of sensors to avoid chattering can be achieved through digital processing with appropriate filters, after studying the nature of the noise measured with the sensor’s speed signal. However, overcoming sudden disturbances and loads is more effective with STSMC.

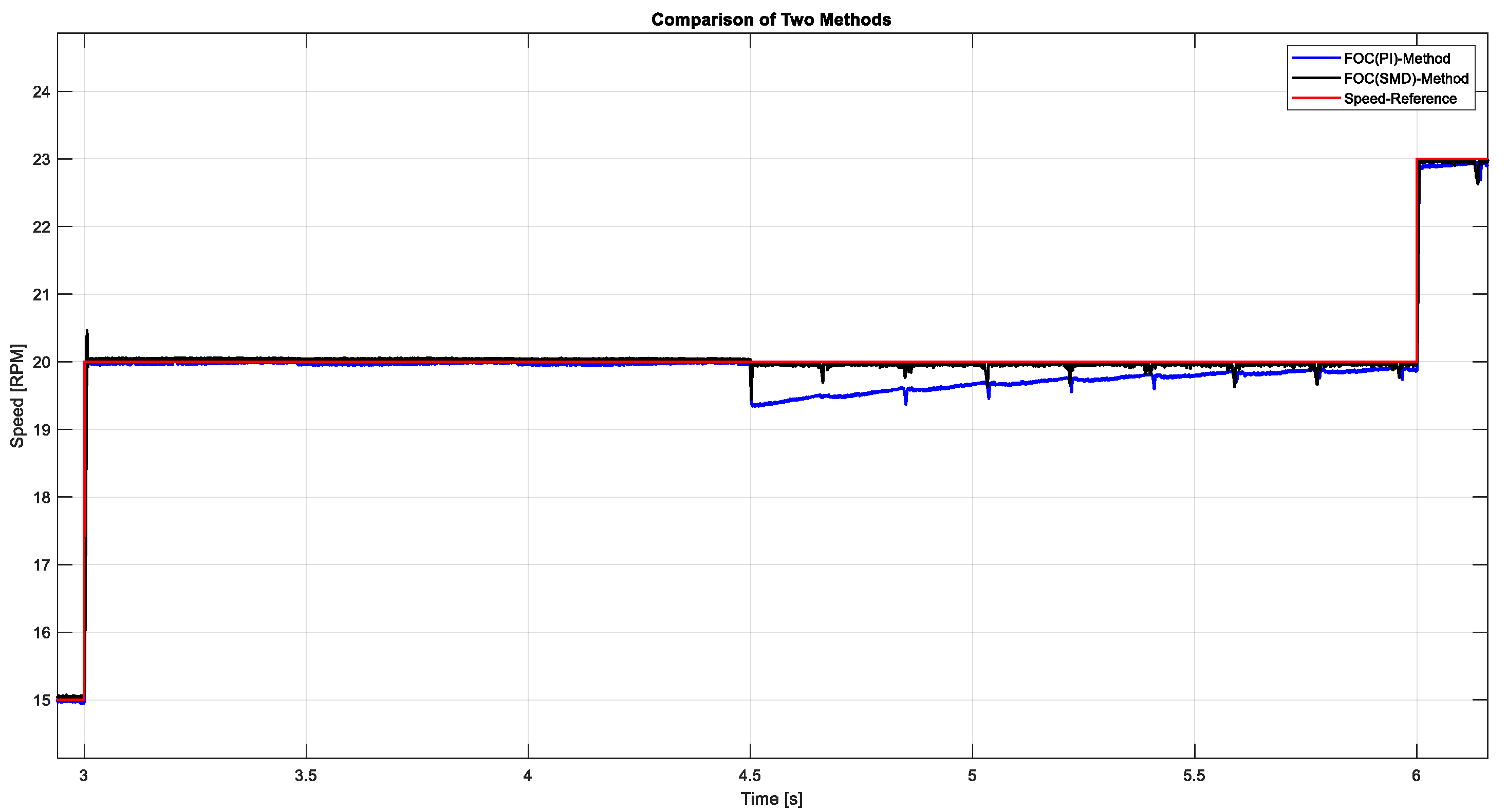

Figure 14 shows the speed response to a step input using the classic FOC method and the FOC method with SMC. The results show the speed response to a sudden load of 50 N·m at 4.5 s The results clearly demonstrate the superior adaptability and robustness of the nonlinear SMC controller. Following the load application, the FOC-SMC system exhibits a significantly smaller speed drop, faster recovery, and minimal oscillation, quickly returning to the target speed with negligible steady-state error. In contrast, the FOC-PI controller experiences a more pronounced speed deviation, a longer settling period, and noticeable oscillatory behavior before stabilizing.

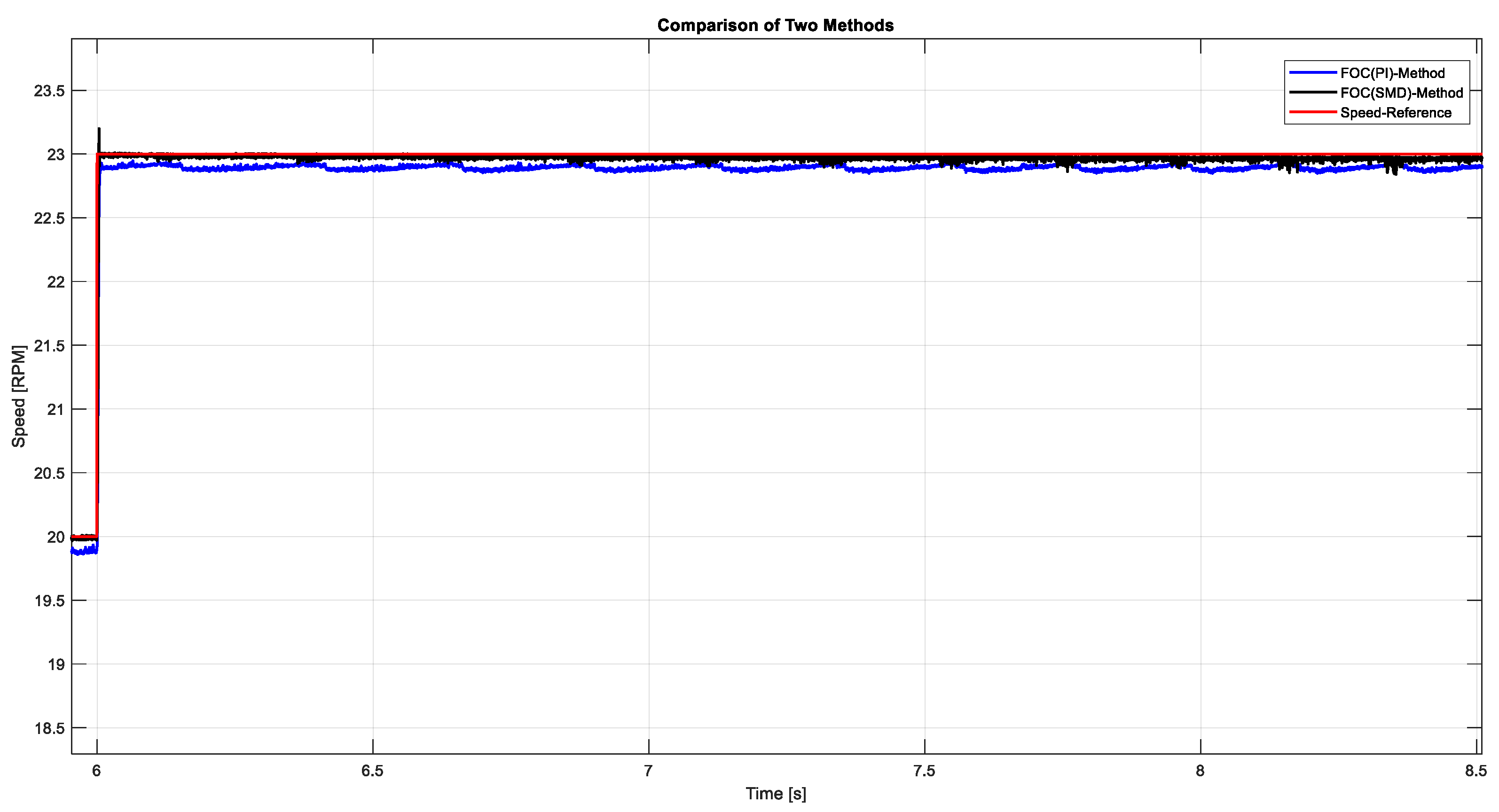

Figure 15 illustrates the motor speed response under a gradually increasing ramp load, which rises from 0 to 60 N·m, simulating the progressive engagement of the cutting head into a coal seam or a transition from soft to harder geological strata. The figure compares the performance of Field-Oriented Control with Proportional-Integral (FOC-PI) and FOC with Sliding Mode Control (FOC-SMC).

As the load ramps upward—particularly within the critical range of 20 to 50 N·m—the SMC-based controller demonstrates significantly greater rigidity and robustness, maintaining the target speed with minimal deviation and a consistently steady response. In contrast, the FOC-PI controller exhibits a gradual but clear speed droop as the load increases, reflecting its limited ability to compensate for slowly varying disturbances without integral wind-up or loss of precision.

If the speed is set to a constant value without regulation, two situations will arise: either the rocks will require a lower speed than the current setting, resulting in higher energy consumption than expected, or the rocks will require a higher speed than the current setting, resulting in higher time consumption. The following table shows the power consumed at a constant speed of 35 RPM with a torque of 150 N·m and at variable speeds proportional to the hardness of the rocks, according to the GSI standard (

Table 5), within 100 s. Using the FOC method with SMC, we can see that the energy consumed at a constant speed is higher than at variable speeds. This method saved almost 3.3% of energy (

Table 7).

In comparison with previous research [

36,

37], it was confirmed that energy savings could be obtained by using a controlled speed pattern on the track. Results showed energy savings ranging from 3.3% to 6.6%.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and validated an advanced control system for a roadheader cutting head, integrating a Geological Strength Index (GSI)-based adaptive speed strategy with high-performance Field-Oriented Control (FOC). The system’s core innovation is the real-time adjustment of cutting head speed (23–46 RPM) based on estimated rock hardness, optimizing the process for efficiency and energy use.

Comparative simulations demonstrated the clear superiority of the Super-Twisted Sliding Mode Control (FOC-STSMC) over the conventional Proportional-Integral (FOC-PI) approach. FOC-STSMC achieved a significantly faster settling time (0.05 s vs. 0.3 s), lower steady-state error, and exhibited superior robustness against sudden and ramp load disturbances typical of heterogeneous coal seams. Quantitative analysis using the ITAE criterion confirmed improvements of 43.7% (no-load) and 15.15% (under load). Furthermore, the GSI-driven variable speed strategy yielded consistent energy savings of 3.3–3.95% compared to constant-speed operation. While FOC-STSMC showed expected sensitivity to high-frequency measurement noise—a challenge addressable with standard filtering—its overall robustness makes it highly suitable for harsh mining environments.

In summary, the synergy of real-time geological assessment and robust FOC-STSMC presents a transformative solution for roadheader automation, promising enhanced cutting efficiency, reduced energy consumption, extended equipment life, and improved safety. Future work will focus on hardware-in-the-loop validation and refining image-processing algorithms for low-visibility conditions to enable field deployment.