1. Introduction

Mine hoisting equipment is the most popular way to transport cargo in mines [

1,

2,

3]. With the development of scientific and technological progress and the growing demands of mining companies, the design and control systems of such machines are constantly being improved. This paper discusses the development history, current status, and trend of improving mine hoisting equipment in order to ensure more efficient, safe, and reliable operation [

4,

5,

6].

High-grade electro-hydraulic gate control systems, medium-voltage three-level high-power frequency-conversion systems, and other technologies have reached maturity and are widely used.

Mine hoisting equipment plays a vital role in the mining industry, responsible not only for lifting minerals and transporting personnel, but also for transporting materials and equipment. Current technological development [

7,

8,

9] focuses on the optimization of structural design, improvements to hydraulic braking systems, and technological innovation in control and transmission systems, and these achievements contribute to key technological breakthroughs in heavy-duty and ultra-deep hoists [

10,

11,

12]. Energy storage technologies such as flywheel energy storage [

13,

14,

15], supercapacitors, and hydraulic energy storage [

16,

17,

18] show great potential in energy conservation and environmental protection. The transition from automated control to automatic control [

19,

20,

21] improves the safety and reliability of the system through intelligent network control. Thus, the design trends of these machines are aimed at energy saving and environmental protection, intelligent control [

22,

23,

24], intelligent operation and the development of hoisting equipment for ultra-deep wells, the intelligent control system of which will allow the machine to achieve self-adaptation of the load [

25,

26,

27], self-regulation of torque, flexibility, and fully autonomous operation. Market analysis shows that the mine hoist market is expected to grow significantly, which is explained by the growing demand for energy resources and metallic and non-metallic minerals worldwide. Future research and development will continue to advance mine hoist technology, making it more efficient, intelligent, and environmentally friendly.

In mine hoists, protecting the motor and extending its service life can save significant costs. From the perspective of the motor’s motion trajectory, the acceleration jump will damage the motor structure. Therefore, in order to protect the motor, the use of a seventh-order S-curve can optimize the motor’s motion trajectory and achieve the purpose of protecting the motor. First, in terms of energy conservation and consumption reduction, its exceptional smoothness significantly suppresses abrupt changes in motor torque and current, directly reducing peak power demand and ineffective energy consumption during startup, shutdown, and speed adjustment processes. This enhances overall energy efficiency and reduces carbon emissions during operation. Second, in extending equipment lifespan, the curve effectively minimizes dynamic stress and fatigue wear on transmission systems (such as steel cables and gears). This not only reduces resource consumption and waste generated from manufacturing and replacing components but also lowers the carbon footprint associated with equipment maintenance over its entire lifecycle. The study includes information on the protection of machinery materials, which indirectly serves as evidence of its environmental benefits.

This paper establishes a hoist model in MATLAB 2024a 64 bit, which utilizes a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM) model as the primary power source. A PID control algorithm is employed, where the control system employs a cascade structure. The speed PID controller takes the velocity error (the difference between the reference speed from the seventh-order S-curve and the actual motor speed) as its input and outputs the reference for the q-axis current (i_q_ref). The current PID controllers then use the error between the reference and measured dq-axis currents to generate the voltage commands for the motor. After proportional, integral, and derivative operations, the controller outputs the control signals for the PMSM, namely the d-axis and q-axis voltages. These voltages then undergo inverse Park and inverse Clarke transformations to generate three-phase voltages, which are converted into PWM waves. These PWM waves serve as the input signals to the PMSM, controlling its rotational speed. To ensure smoother motor operation, a seventh-order velocity profile algorithm is used as the reference speed signal for the PID controller, optimizing the motor’s motion trajectory. In the article, a comparative analysis of energy savings is conducted through a combination of theoretical modeling, intelligent algorithm optimization, and case simulations. Based on the dynamics of the hoisting system, an energy consumption mathematical model is established. The traditional five-stage speed curve is upgraded to a smoother seven-stage S-shaped speed curve during acceleration and deceleration phases to reduce start-stop impacts and peak energy consumption.

By constraining these high-order physical quantities, the seventh-order S-curve ensures exceptionally smooth variations in motor torque commands (directly corresponding to the drive current). This fundamentally mitigates “impact” and “excitation” on both mechanical and electrical systems. The performance improvements brought by the seventh-order S-curve are substantial, and these enhancements themselves represent innovation. Mining equipment is typically characterized by large scale and high power, such as mine hoists, belt conveyors, large pumps, ventilation fans, and heavy-duty mining trucks. The severe mechanical shocks during startup, shutdown, and speed regulation processes are the primary root causes of equipment failure. In mine hoists, conventional trapezoidal or standard S-curves exhibit discontinuous jerk (rate of change of acceleration) during startup and braking, generating flexible impact. This impact induces severe longitudinal vibrations and lateral oscillations in the steel wire ropes, exacerbating friction with the drum. Long-term exposure to such conditions can lead to “rope biting” (mutual squeezing and wear of wire ropes), posing serious safety risks. The seventh-order S-curve ensures complete smoothness from acceleration to its higher-order derivatives. This means tension variations in the wire rope are extremely gradual, fundamentally suppressing longitudinal elastic vibrations. Consequently, it significantly reduces the risk of rope biting and slippage between the ropes and linings, directly enhancing intrinsic safety levels.

2. Analysis of the Design of a Mine Hoisting System

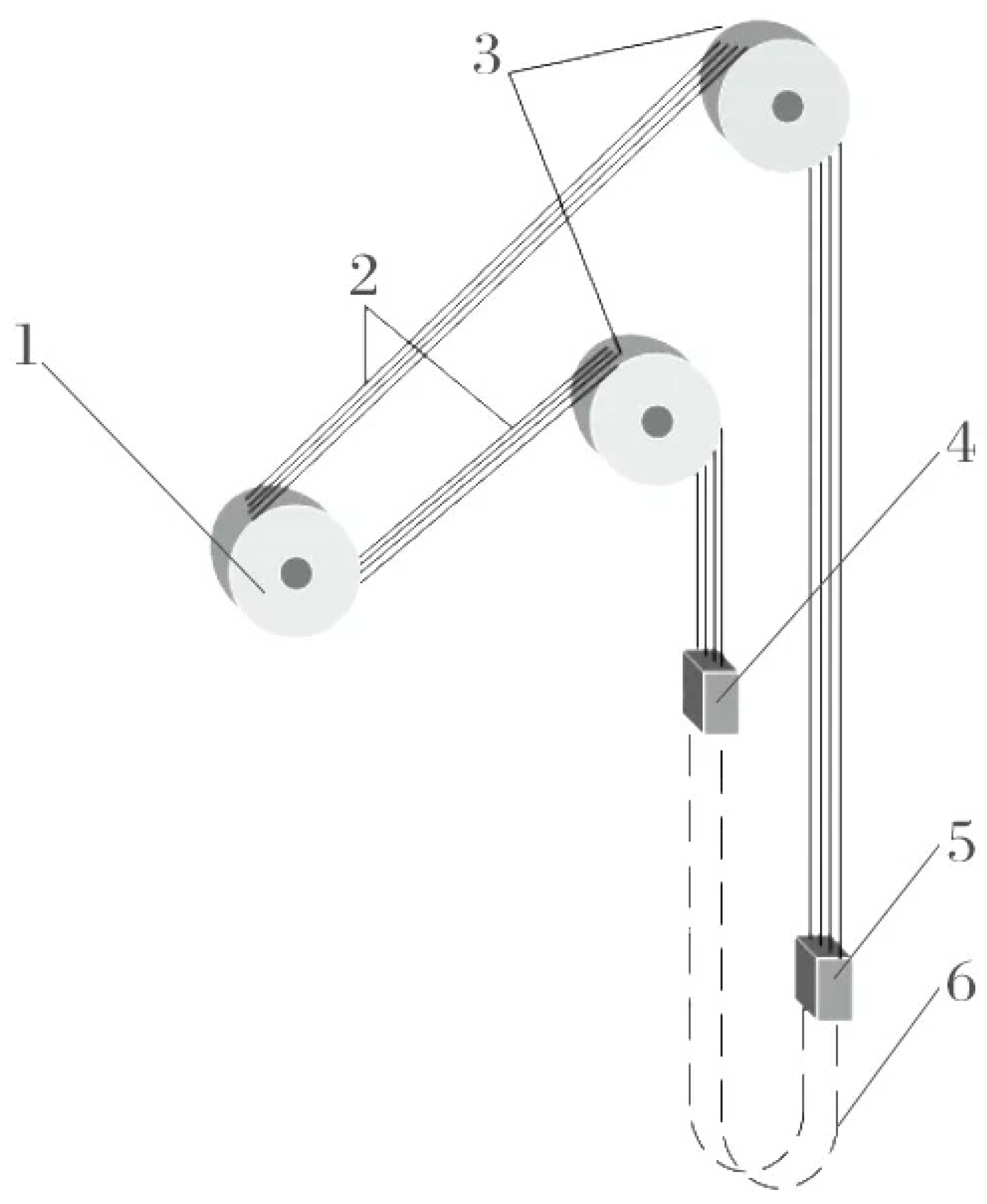

Figure 1 shows the design of a mine hoisting installation, including a friction pulley 1, hoisting ropes 2, steering pulleys 3, cargo vessels 4–5, and tail rope 6.

The hoist is a large electromechanical-hydraulic and electrical complex that contains an electric motor, spindle unit, depth indicator, braking device, control system, and operator’s console. Currently, two types of mine hoists are widely used—winding and friction. The friction pulley serves as the driving force, and its controlled acceleration and deceleration via a smooth S-shaped velocity curve are crucial for avoiding operational shocks. The hoisting ropes act as the primary load-bearing element, transmitting force through their mechanical strength and elasticity, providing the foundation for safety. The tail ropes provide a balancing function by compensating for weight disparities, minimizing tension differences across the friction pulley, thereby preventing slip, ensuring reliable frictional force transmission, and significantly reducing fluctuations in drive power. By employing specialized linings with a high friction coefficient and designing rational rope grooves to optimize the contact mechanics, the system works in deep synergy with the S-shaped velocity curve. This integration ultimately achieves smooth, stable, and uniform power transmission. As a result, it fundamentally prevents destructive slippage and impact wear, minimizes the wear rate during normal operation, and significantly extends the equipment’s service life.

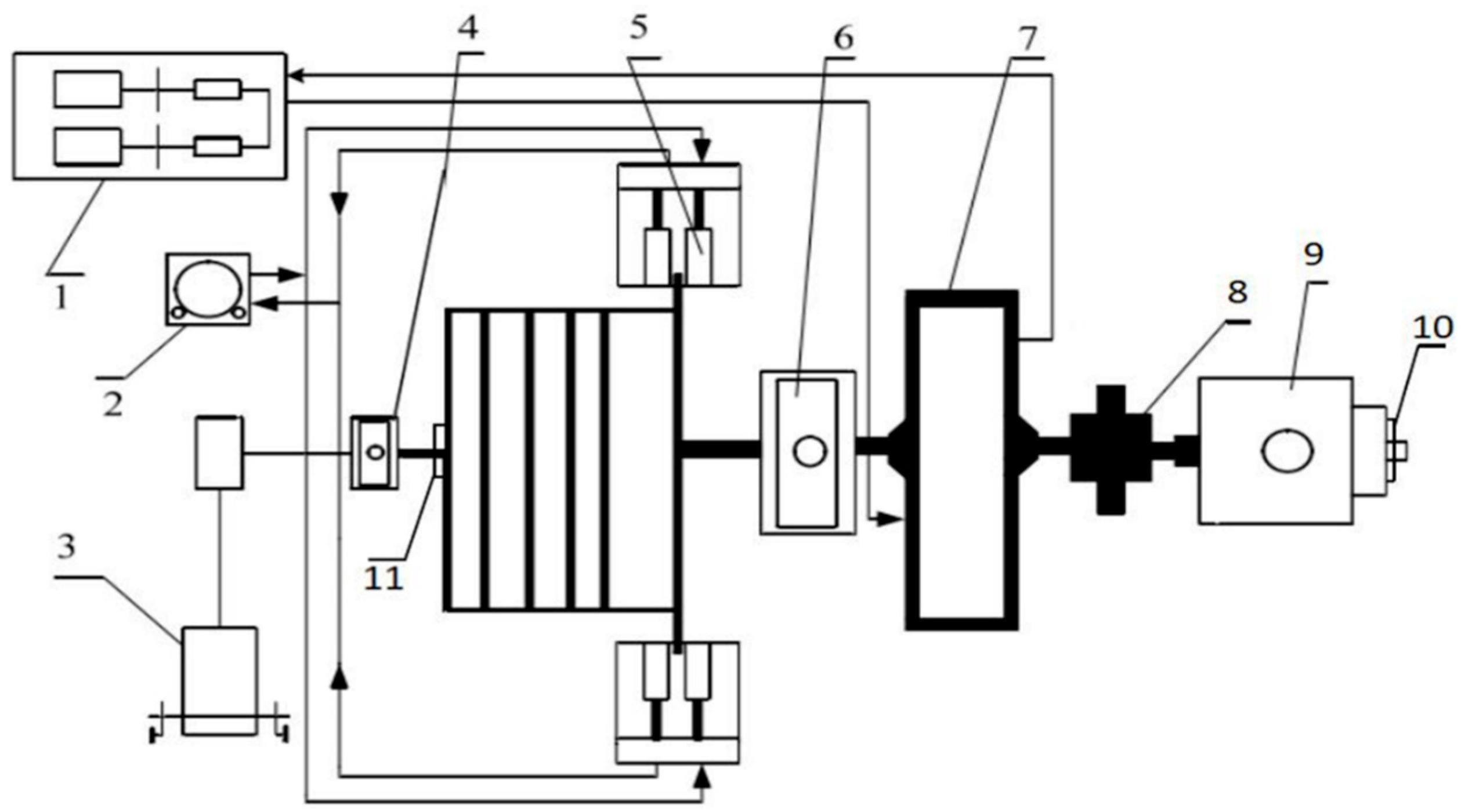

The electromechanical part (

Figure 2) comprises a lubrication pump (1), a hydraulic station (2), a depth indicator (3), a spindle unit (4), a disk brake (5), a main bearing (6), a gearbox (7), an electric motor (9), and angle sensors (10 and 11).

The working mechanism consists of a main bearing and a main shaft unit. The main shaft unit consists of six parts: a main shaft, a support pulley, a drum, rolling bearings, a brake pulley, and a rope adjustment clutch. Together with the main bearings, these parts provide winding and unloading of the rope, which allows the hoist to withstand all loads for transportation.

The hydraulic brake system includes a hydraulic transmission device and a brake. In case of emergency braking or slowing down and stopping, the hydraulic brake system can brake the drum in time and quickly stop the machine for safe braking of the cargo vessel. The lubrication system consists of a pump station and pipelines. During the operation of the hoist, the lubrication system continuously supplies lubricant to the gears and bearings, ensuring their normal operation. The lubrication system is connected to the engine and the automatic protection system. If the lubrication system fails, the main engine is de-energized, which ensures the safety of personnel when working with the unit.

The mechanical transmission consists of a reducer and a clutch. When transporting a cargo vessel, the reducer is responsible for slowing down and transmitting power, and the clutch is responsible for connecting rotating parts and transmitting power. The reducer and clutch are key components for reducing speed, connecting, and transmitting power from the hoist, thereby increasing the hoist’s service life.

The detection and maneuvering system consists of an operator panel, a shaft sensor, a drive, and a depth indicator. It is mainly used to control the hoisting system, detect speed, lift and lower, display depth, etc. At the same time, the operator panel displays the current status of the main characteristics of the hoisting unit.

The automatic control system consists of an alarm system, an automatic protection system, and an electric motor control system. The main purpose of the system is to provide the power required for elevator lifting and lowering during operation. The alarm system mainly collects operating data from the elevator’s detection sensors and transmits it to the control system, enabling accurate elevator operation control. The motor control system controls the elevator according to the data transmitted by the alarm system to accurately carry out the commands of the transportation task. In case of failure, the automatic protection system stops the main motor and applies the safety brake to ensure the safe and stable operation of the lifting device [

28,

29,

30].

3. Analysis of the Simulation Model of the Electric Motor of the Installation

This article discusses the control of an electric motor using a proportional–differential–integral controller (PID controller) MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

To create a mathematical model, we will use the following: basic physical relationships.

The mechanical equations of the motor’s motion are specified by the moment balance equation:

where

is the moment of inertia;

is the damping coefficient;

and

are the rotation angle and angular velocity of the electric motor shaft, respectively,

and

are the electromagnetic torque and load torque, respectively.

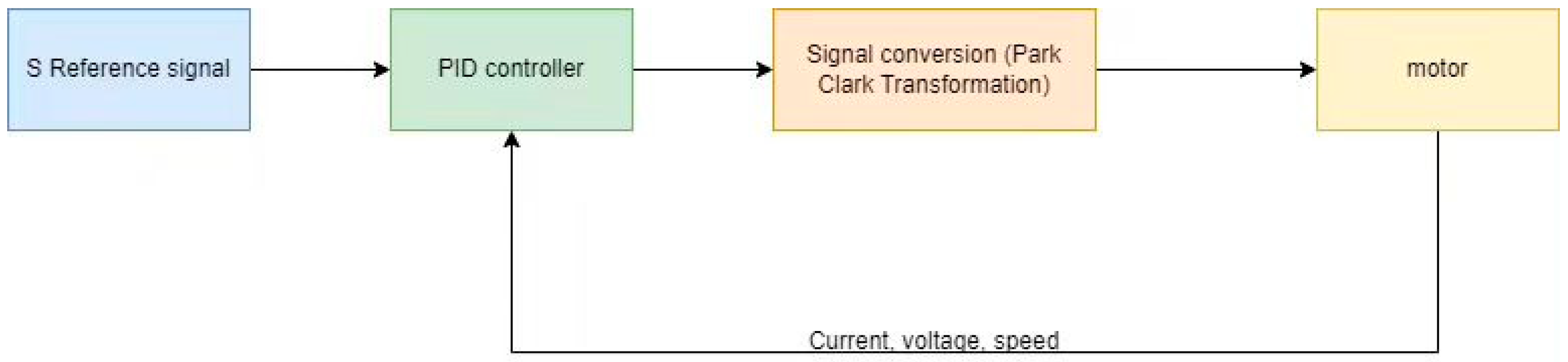

Figure 3 shows the hoist control flow chart. The article uses PID control. The PID’s high inner loop bandwidth allows for rapid tracking of changes in the q-axis reference current, suppressing torque fluctuations caused by sudden load changes. Anti-integral windup is also implemented in the PID to prevent excessive integration and large overshoots during sudden load changes.

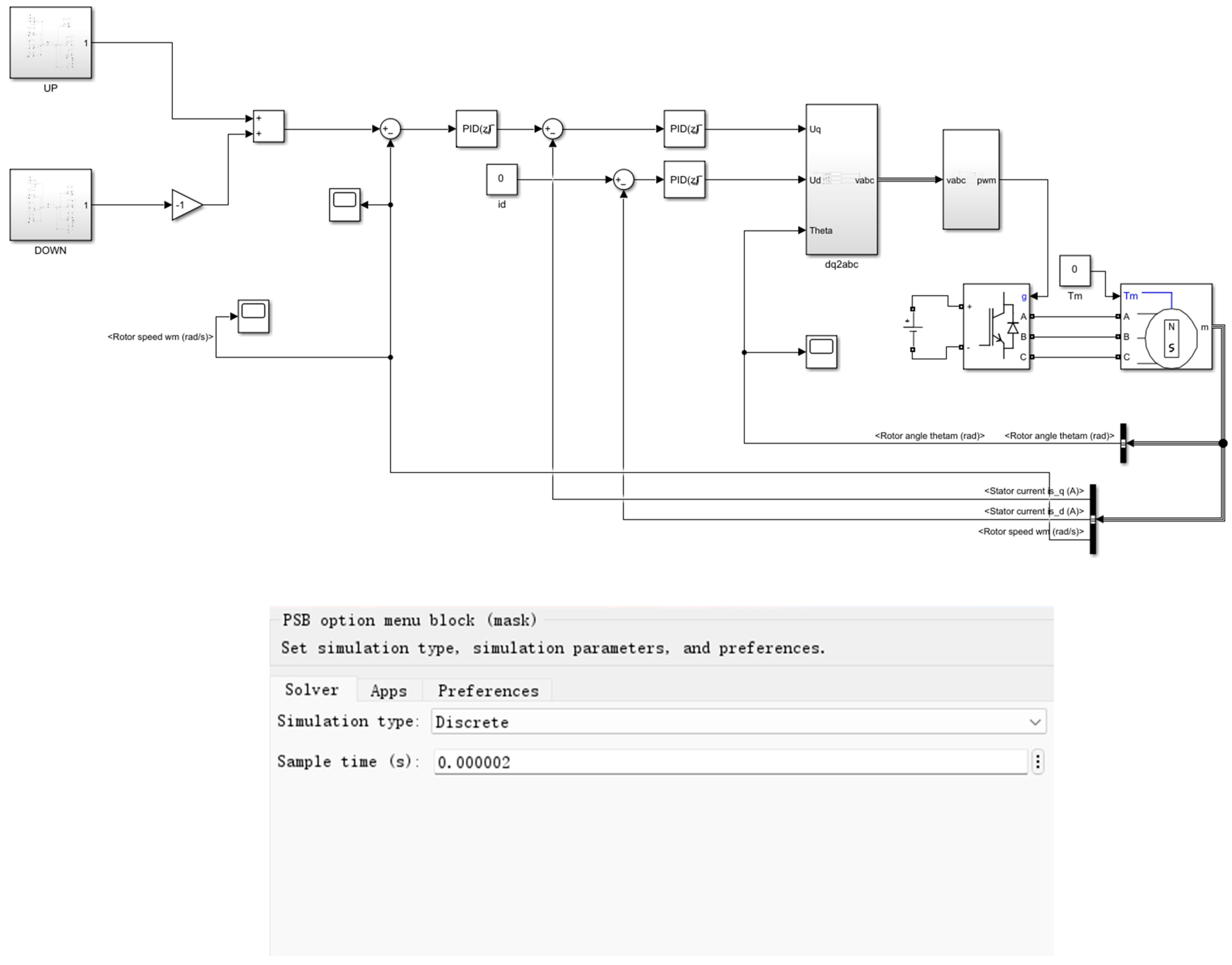

The “up” module represents the section in

Figure 4 where the velocity is positive, while the “down” module corresponds to the portion with negative velocity. The parameters of the PID Controller in the diagram are as follows: P = 10, I = 100, D = 0. The parameters of PID Controller2 are as follows: P = 2.5, I = 40, D = 0. The parameters of PID Controller1 are as follows: P = 4, I = 45, D = 0. The motor control circuit includes an S signal module, a PID module, a motor module, a parking module, and a Clark module. The S signal module contains an S wave, which is mainly used to provide the motor reference signal, the PID module implements the proportional-integral-derivative (PID) algorithm to control the motor speed, and the Park module transforms the variables of the three-phase stationary coordinate system (ABC or αβ) into the variables under the rotating coordinate system (dq axis). The Clark Transform module transforms the three-phase stationary coordinate system (ABC) to the two-phase stationary coordinate system (αβ). The permanent magnet synchronous motor module outputs the dynamic response of torque, speed, and rotor position angle (θ), and supports seamless connection with the Park/Clark transform, PID controller, inverter, and other modules to achieve closed-loop control.

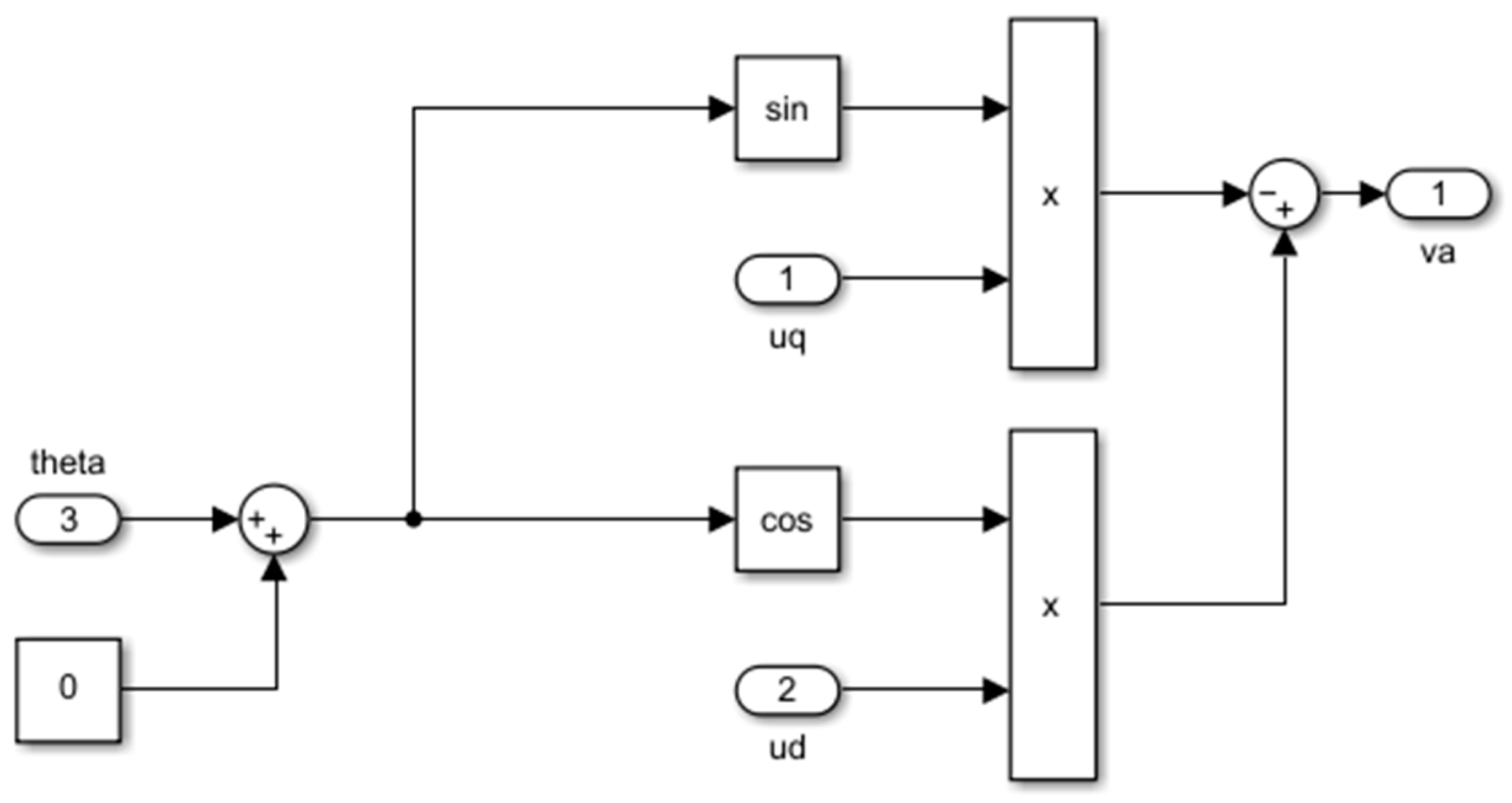

Figure 5 shows the partial Inverse Park transform, and the formula is as follows:

The module in

Figure 5 transforms the currents from a three-phase AC motor through a mathematical conversion, ultimately creating an equivalent process for control on a rotating DC motor model.

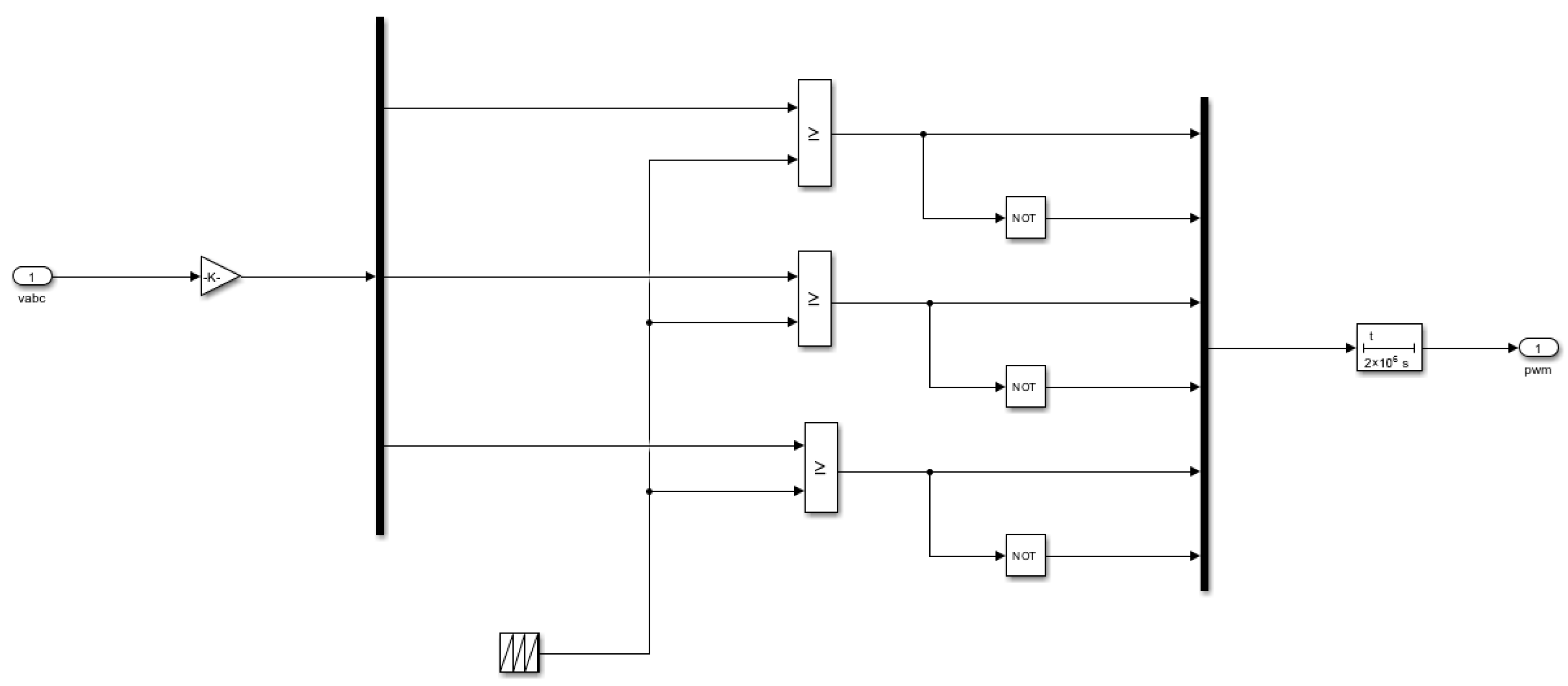

Figure 6 converts the transformed voltage into a PWM wave, which is then used as the input signal for the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM).

4. S-Shaped Control Curve

At present, the S-shaped speed curve is mainly used to control the running of the mine hoist. In this paper, to further improve the performance of the hoist, a seventh-order S-curve will be used to control its operation. In the traditional five-stage speed curve, the maximum values of speed, acceleration, and momentum of the cargo vessel are fixed based on interval data and expert experience, which meet the basic operating requirements but are difficult to reduce system energy consumption. Unlike traditional third- and fifth-order curves, this curve further suppresses sudden jumps and jerks, meeting the strict requirements for vibration protection and smooth operation of hoisting equipment, especially in deep mine workings.

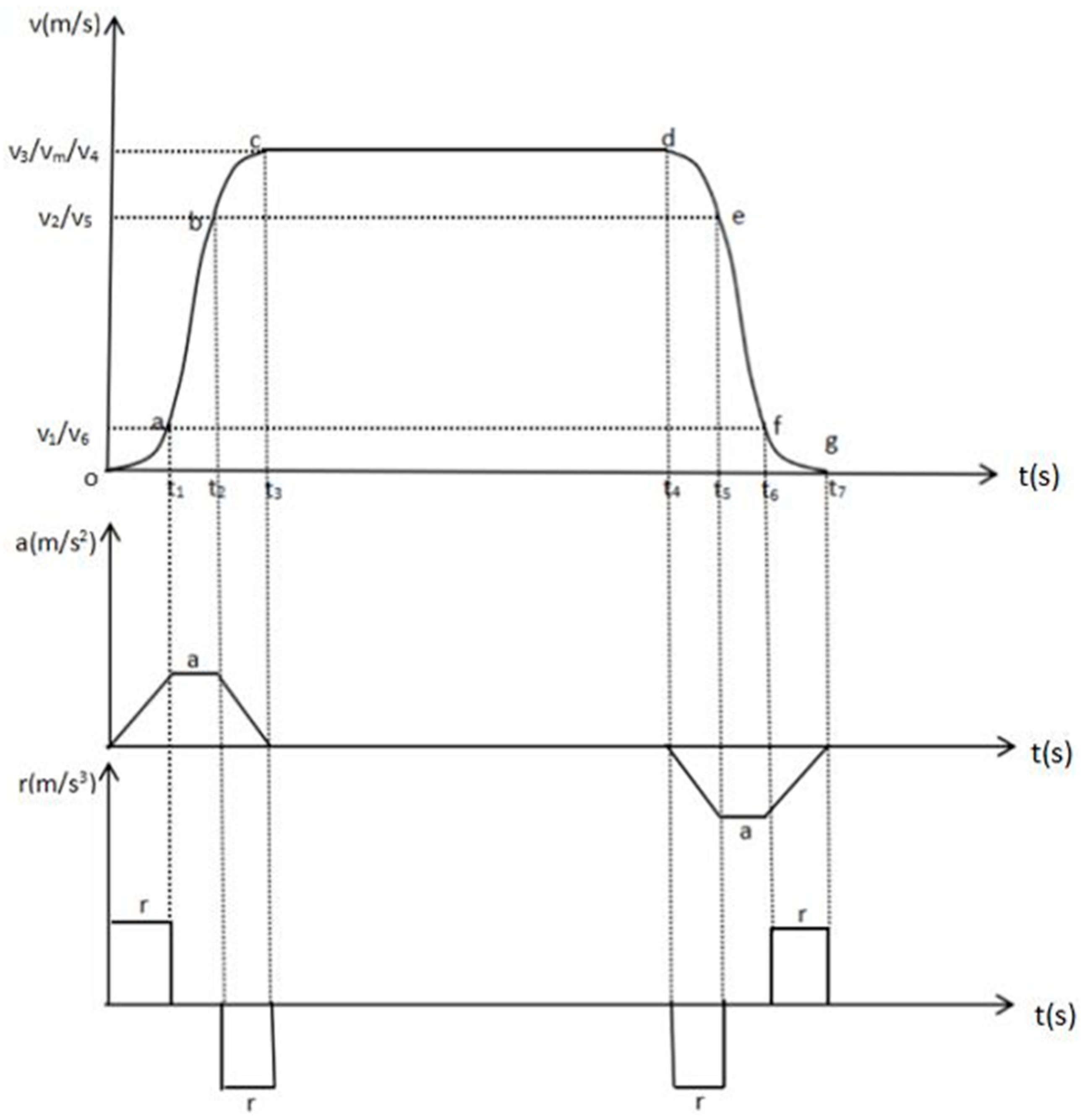

The jerk of a fifth-order curve is linear; its graph is a straight line with a slope. However, at the start and end of the motion segment, this line begins and ends abruptly, creating a step (mutation). This mutation is equivalent to an infinitely high-frequency shock signal. The jerk of a seventh-order curve is a smooth quadratic curve that begins and ends smoothly at zero without any abrupt changes. From

Figure 7 is clear that r is the jerk (the derivative of acceleration); a is the acceleration; and v is the velocity. The X-axis represents time in seconds. In the ascent cycle, the S-shaped velocity curve is divided into a section of initial acceleration (oa), a section of equal acceleration (ab), a section of final acceleration (bc), a section of uniform velocity (cd), a section of initial deceleration (de), a section of equal deceleration (ef), a section of final deceleration (fg), where the deceleration section is symmetrical to the acceleration section, The absence of segments like a–b and e–f in the fifth-order curve does not represent a loss of function but rather a qualitative leap in performance and the expressions for each section are as follows:

Initial acceleration of section oa at 0 <

≤

, where

In the formula is the winch speed, m/s; is the distance traveled in this stage, m; is the operating time, ; r is the impulse value, m/s3, a is the acceleration of the lift, m/s2.

Uniformly accelerated section ab, when

<

t ≤

time is known:

In the formula is the winch speed, m/s; s2 is the distance of the given stage, m; − is the operating time, s.

The end of the variable acceleration of the b–c section, when

<

t ≤

when it is known:

where

is the speed of the lift, m/s;

s3 for this stage is the travel distance, m;

−

is the travel time, s.

Equation for a uniform speed section

The uniform speed on the section c–d, when

≤

t ≤

time is known:

In the formula is the maximum speed of the lifting curve, as well as the speed of the uniform section, m/s; is the speed of the lift, m/s; s4 is the distance of the run of this stage, m; s is the total distance of the run, m; − is the operating time, s.

Formula for the deceleration section

The initial section of variable deceleration (d–e), when

<

t ≤

is known:

In the formula is the winch speed, m/s; s5 is the distance of the run of this stage, m; is the operating time, s.

Uniformly decelerating section e–f, when

<

t ≤

. When

In the formula,

v6t is the winch speed, m/s;

s6 is the distance of the run of this stage, m;

is the operating time, s. The final variable section of deceleration (f–g), when

<

t ≤

is known when

In the formula. is the speed of the lift, m/s; s7 is the distance of the run of this stage, m; is the operating time.

The total lifting cycle is as follows:

The seventh-order S-curve serves as the reference speed input to the PID controller of the permanent magnet synchronous motor, enabling optimized speed control of the motor. The relevant motor parameters are as follows: Stator phase resistance Rs (Ohm): 0.0485; Armature inductance (H): 0.000395; Inertia, viscous damping, pole pairs, static friction [J(kg·m2) F(N·m·s) p() Tf(N·m)]: [0.0027, 0.0504924, 1, 0]. The motor operates stably when the rotational speed reaches 500 revolutions per second.

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM). According to the different arrangements of permanent magnets on the rotor, PMSM can be divided into internal and surface. In this paper, an internal PMSM (hereinafter referred to as permanent magnet synchronous motor) is selected as the main traction motor of the mine hoist, which has the following advantages compared with other types of motors:

Small size, light weight, and easy installation.

PMSM uses permanent magnets instead of excitation windings to generate a magnetic field, so there is no resistance loss, resulting in a decrease in the amount of reactive power received, and therefore higher energy efficiency and low heating.

The mechanical characteristics of PMSM are more rigid than other types of motors, and they have a high ability to withstand load changes.

There is no rotor resistance and hysteresis loss, so the motor efficiency is greatly improved.

The power factor is high, and under full load, the power factor can be close to 1, which can further reduce the energy consumption βof the motor. Basic structure, which is mainly composed of the saddle, bearing, stator winding, stator core, rotor core, permanent magnet, rotor shaft, end cover, and other parts. The basic working principle is to generate a rotating magnetic field through the stator winding, and then, based on the interaction between the magnetic field of the permanent magnet and the magnetic field of the stator, an electromagnetic torque is generated to drive the rotor of the PMSM. When the frequency of the stator winding current is kept constant in the permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM), the rotor speed is also kept constant and is proportional to the frequency of the stator winding current.

where

n is the rotor speed (also known as synchronous speed);

f is the stator winding current frequency (i.e., the frequency of three-phase sinusoidal AC);

is the number of pole pairs of PMSM.

There is relative motion between the stator and the rotor of PMSM, and the stator and rotor are coupled to each other through the air gap magnetic field, so its internal electromagnetic coupling is very complex. In the ABC coordinate system, the electric and magnetic structures of the rotor of a synchronous motor are not symmetric, and the mathematical model of PMSM is a set of nonlinear time-varying differential equations, which makes its dynamic performance analysis and control strategy study very complex [

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, the mathematical model of PMSM can be greatly simplified by using coordinate transformation to create a two-phase coordinate system, i.e., a dq coordinate system that rotates synchronously with the rotor of PMSM and such that the dq axis of the coordinate system always coincides with the pole axis of the rotor of PMSM [

34,

35].

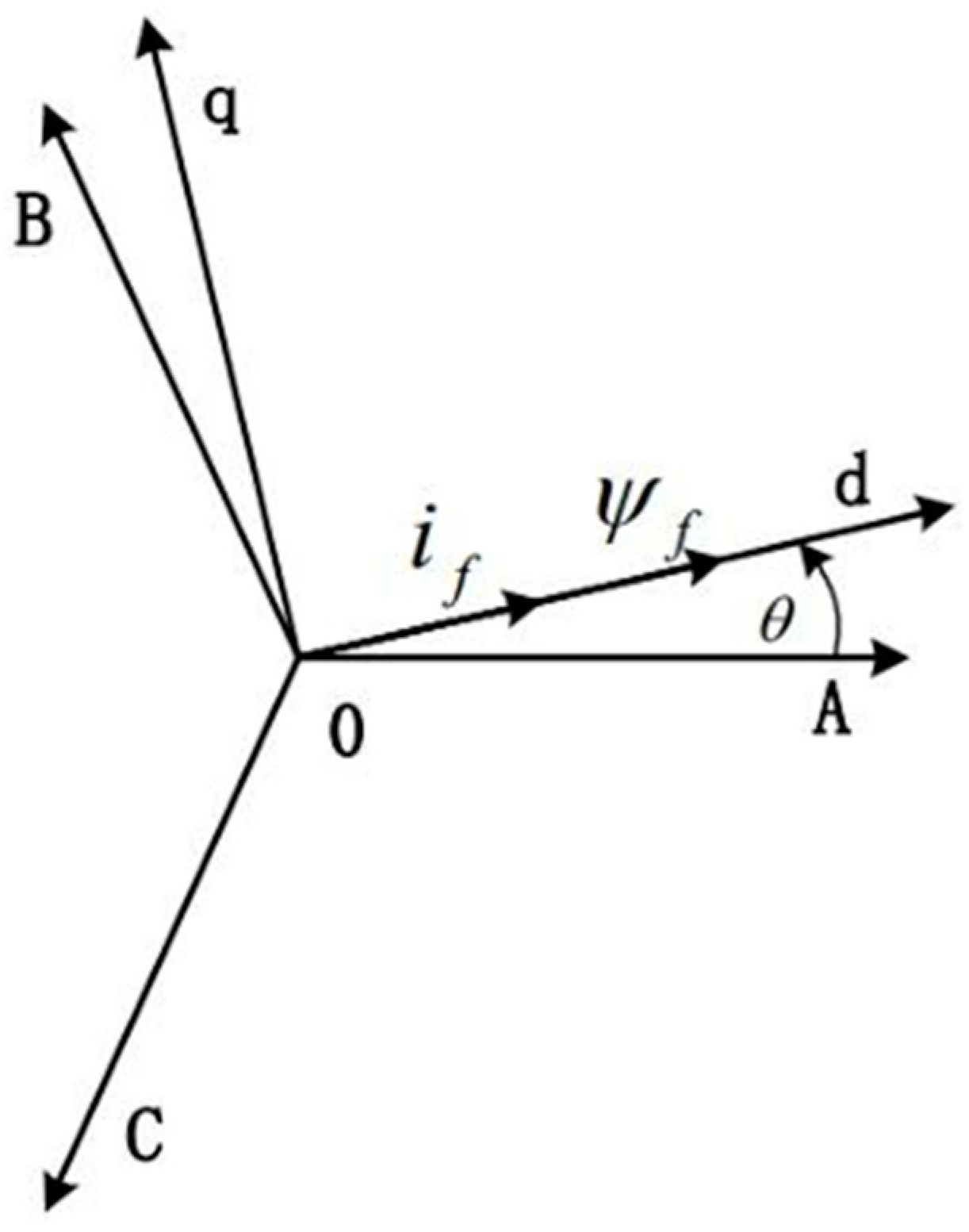

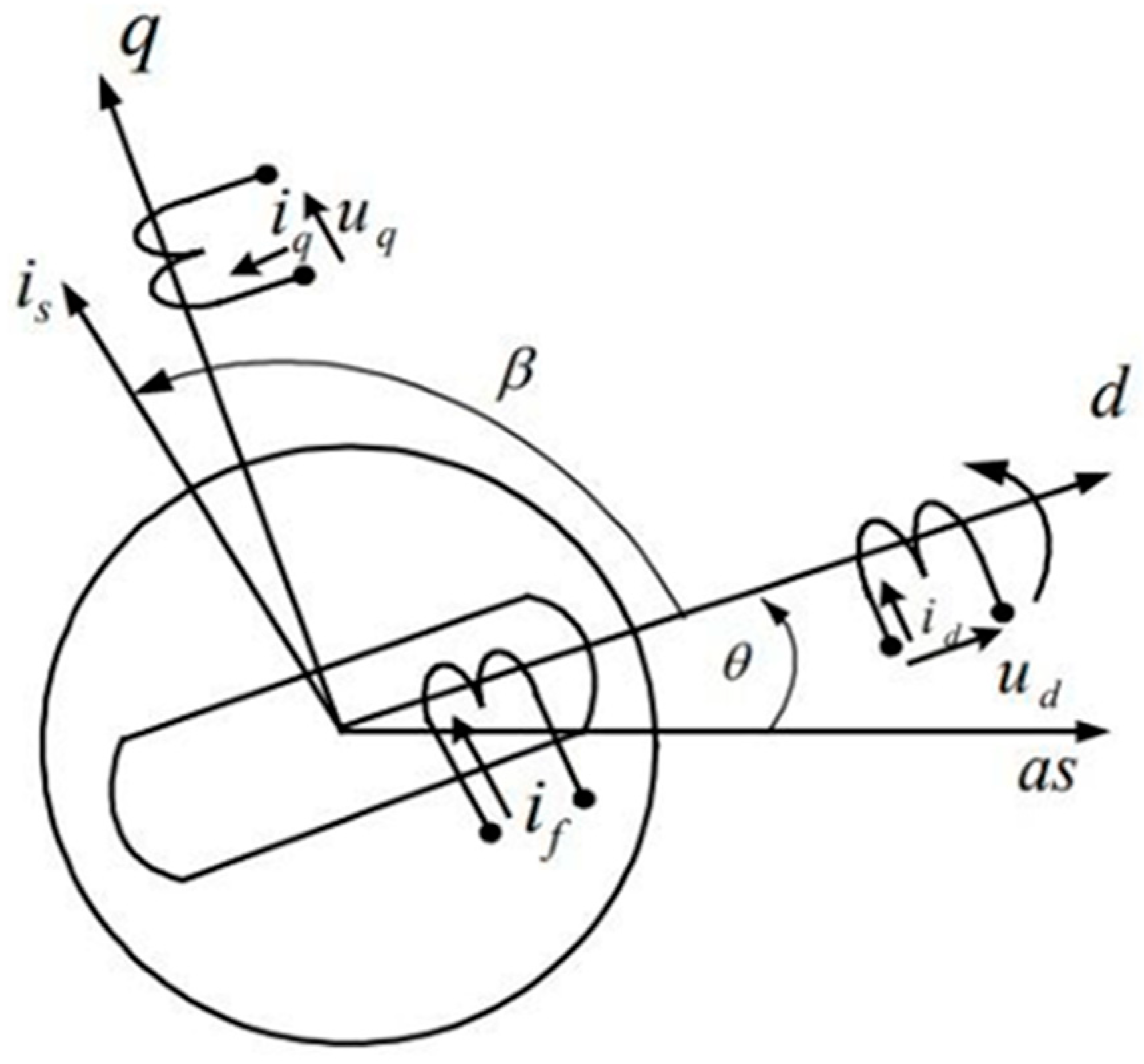

As shown in

Figure 8, the dq coordinate system is a coordinate system rotating synchronously with the stator magnetic field of the PMSM, since the d-axis always coincides with the pole axis of the PMSM rotor, so the direction of the d-axis coincides with the direction of the rotor magnetic circuit of the PMSM, and the q-axis always leads the d-axis by 90°. The equivalent model of the PMSM in the dq coordinate system is shown in

Figure 8.

In

Figure 9: β is the moment angle: the angle between the spatial vector formed by the three-phase stator currents of the PMSM and the magnetic field axis of the permanent magnet; θ is the angle between the magnetic field axis of the permanent magnet (d axis) and the magnetic field axis A, the magnetic field axis of the phase winding;

is the excitation circuit of the poles of the rotor permanent magnet;

is the spatial vector formed by the three-phase stator current;

is the stator excitation component of the winding current;

is the torque component of the stator winding current. The transformation matrix from the ABC coordinate system to the dq coordinate system has the form:

Formula (17) is the Park transformation, which converts the three-phase stator current from the fixed three-phase stationary coordinate system to the two components in the rotating coordinate system dq. , , is the three-phase stator current, and are two components in the rotating coordinate system.

Based on the given transformation matrix, a mathematical model of PMSM can be obtained in the dq coordinate system.

The stator voltage equation has the form:

where

,

are the components of the stator voltage vector along the dq axis;

,

are the components of the stator winding current vector along the dq axis,

,

are the components of the stator flux linkage along the dq axis;

ω is the electrical angular velocity of the rotor (rotor angular frequency);

β is the differential operator.

The equation of the stator magnetic circuit has the form:

where

,

are the equivalent synchronous inductances of the dq axis. It is seen that when the alternating magnetic field generated by the permanent magnet of the PMSM rotor is transformed into the dq coordinate system, the magnetic field creates a flux linkage only with the d-axis winding of the stator winding, i.e.,

, and the inductance coefficient does not depend on the angle.

The equation of the electromagnetic torque is as follows:

where

is the output torque of the PMSM (electromagnetic torque);

is the number of pairs of magnetic poles of the PMSM.

The equation of the balance of motion is as follows:

where

is the total load moment on the motor shaft;

J is the rotational inertia on the motor shaft;

np is the number of pairs of magnetic poles of the PMSM;

ω is the electrical angular velocity of the rotor (rotor angular frequency).

It can be seen from the above equation that the output torque of PMSM can be divided into two parts: one part is the torque of permanent magnets arising from the interaction of the flux linkage

of the rotor permanent magnet poles and the stator current vector along the q axis, and the other part is the torque of resistance arising from the interaction of the stator excitation current component

and the stator current component

. Obviously, both parts of the torque are proportional to the torque component

. Since the amplitude of the rotor permanent magnet flux linkage is constant, the magnitude of the output torque of PMSM depends only on the magnitude of the stator current torque component

, PMSM can be controlled by the orientation of the magnetic circuit of the rotor permanent magnets in the dq coordinate system. On the other hand, the direct axis component

(the excitation component of the stator current) also affects the magnitude of the flux linkage, according to which the effect of weak magnetic acceleration can be achieved. As a result, representing the PMSM stator current in the rotor magnetic field rotation coordinate system dq makes the PMSM speed control relatively simple [

36,

37].

5. Simulation Results

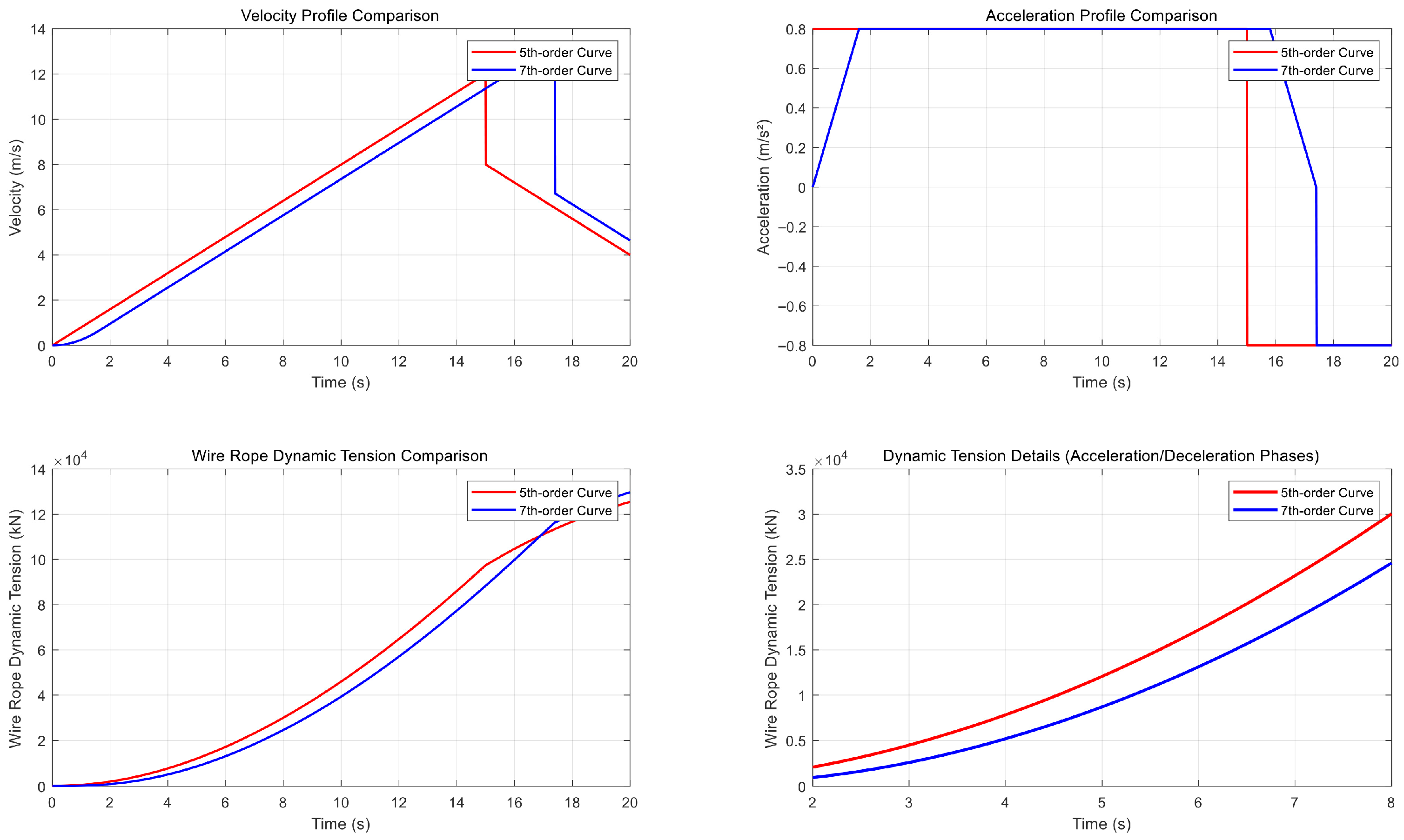

Figure 10 clearly shows that the seventh-order S-curve, by virtue of its smooth acceleration transitions, significantly suppresses the dynamic tension fluctuations in the wire rope. Quantitatively, compared to the fifth-order curve, the seventh-order S-curve reduces the peak dynamic tension by approximately 24% and decreases the tension fluctuation amplitude by about 34%. This data directly validates that the seventh-order S-curve effectively mitigates wire rope vibration intensity and dynamic stress, thereby mechanistically quantifying its contribution to reducing wear risk and extending equipment service life.

The 7th-order S-curve velocity profile significantly reduces wire rope dynamic stress, effectively minimizing vibration and wear risk, thereby extending equipment service life.

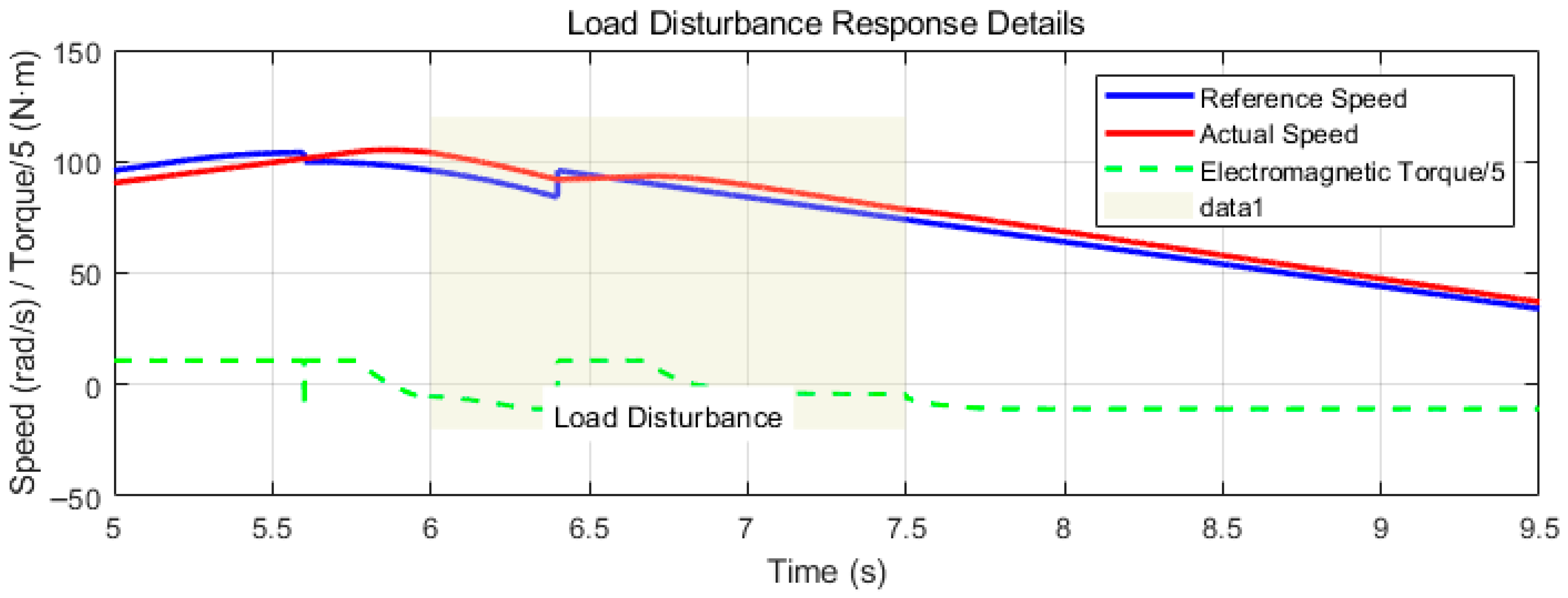

Figure 11 verifies the robustness of the PID controller based on seventh-order S-curve velocity planning against sudden load disturbances during the constant-speed phase through simulation. As shown in the figure, when a 35 N·m step load torque is applied at t = 6 s, the motor speed exhibits only a minor and brief undershoot (approximately 3.5%) and quickly and smoothly recovers to the target speed within 0.25 s. The immediate response of the electromagnetic torque (corresponding to the q-axis current) effectively compensates for the load variation, demonstrating that this control strategy can reliably ensure the stable operation of mine hoists under load fluctuations.

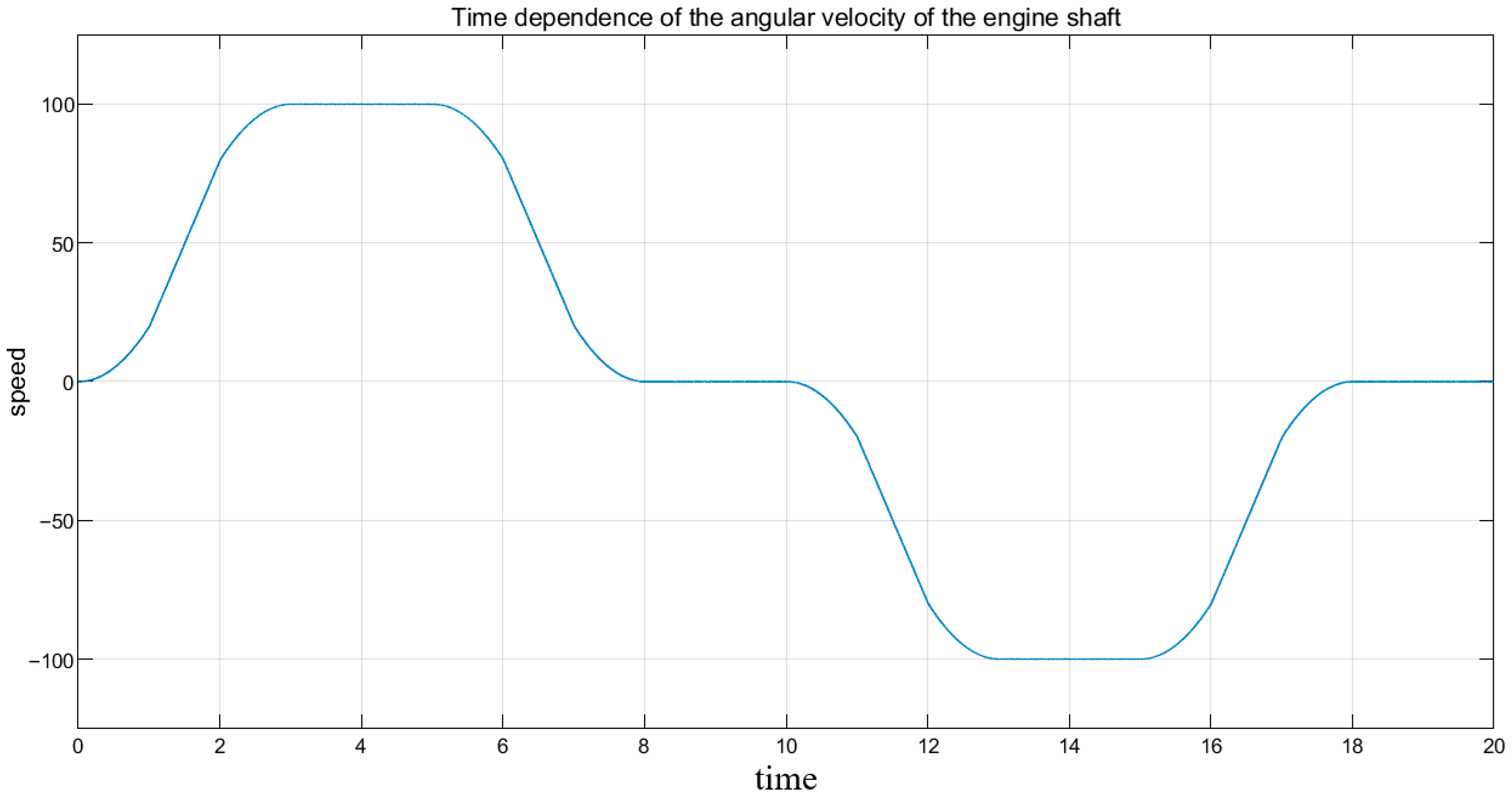

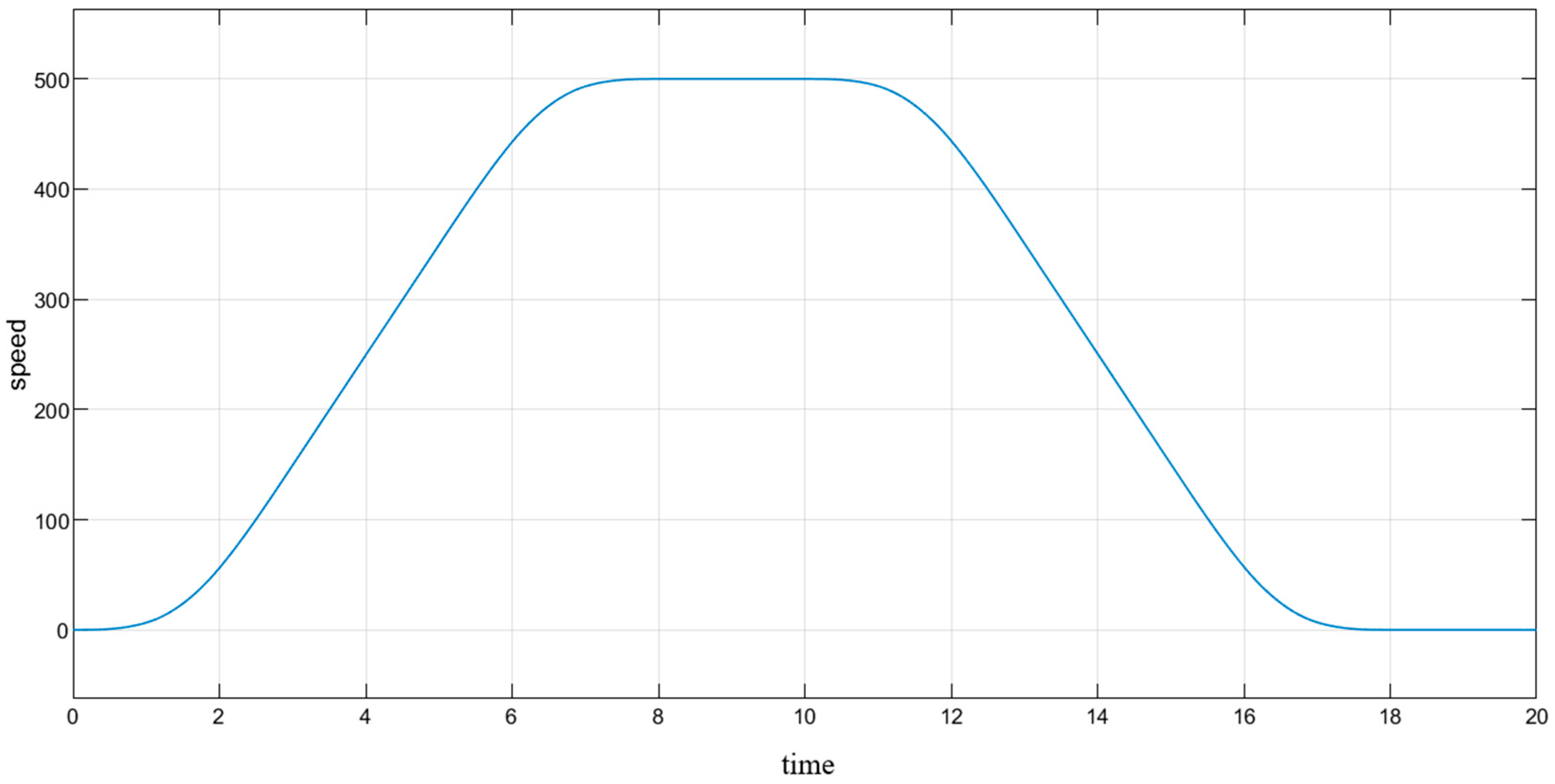

The smooth, continuous S-shaped angular velocity profile in

Figure 12 provides visual validation of its alignment with the high-order S-curve theory. The absence of sharp corners during transitions between acceleration, constant velocity, and deceleration phases proves that acceleration varies smoothly, without sudden jumps. Consequently, the jerk, which is paramount for motion smoothness, is maintained within a finite and controlled range. This control strategy, based on smooth phase transitions, effectively addresses the key challenges associated with ultra-deep mine hoisting. Primarily, it suppresses severe rope vibration and container sway at the source by eliminating abrupt force changes, thereby ensuring the stability and safety of long-distance lifting operations. Secondly, it significantly reduces the impact of stress on both mechanical structures and electrical systems, extending equipment service life while optimizing energy consumption by avoiding power peaks.

This graph is obtained using the S-shaped formula. Positive values correspond to the speed during the ascent phase, and negative values correspond to the speed during the descent phase. In

Figure 12, the x-axis is time, the y-axis is the engine speed, 0–1 s is the slow acceleration phase, 1–2 s is the constant acceleration phase, 2–3 s is the slow acceleration phase, 4–5 s is the constant ascent phase, 5–6 s is the slow deceleration phase, 6–7 s is the constant deceleration phase, 7–8 s is the slow deceleration phase, 8–10 s is the mineral unloading time, 10–18 s is the descent phase.

In

Figure 13: X-axis (time)—time interval of the lifting machine operation (unit: seconds). Y-axis (angle)—change in the rotation speed of the mechanism (unit: rad/s).

Acceleration and deceleration dynamics:

The initial section (0–100 s) shows a smooth increase in angular velocity up to 500 rad/s, which corresponds to the acceleration stage of the lifting system. After reaching the peak, the speed decreases to 0, which indicates the braking or stopping phase of the mechanism.

Curve character:

The shape of the curve is a trapezoidal speed profile, typical for industrial lifts: Linear increase—uniform acceleration. Plateau—stable operating speed. Linear decline—controlled braking. Its continuous jerk effectively suppresses elastic vibrations at the drive end of long wire ropes; Smooth torque control enables gradual management of substantial kinetic/potential energy, reducing mechanical and electrical stress; Gradual power variations facilitate stable recovery of regenerative energy. During implementation, the curve needs to be regenerated and the controllers tuned based on specific equipment parameters, while the core control architecture remains unchanged. Therefore, this strategy provides a viable technical pathway for addressing critical challenges in ultra-deep mine hoisting, including vibration suppression, safe operation, and energy efficiency optimization.

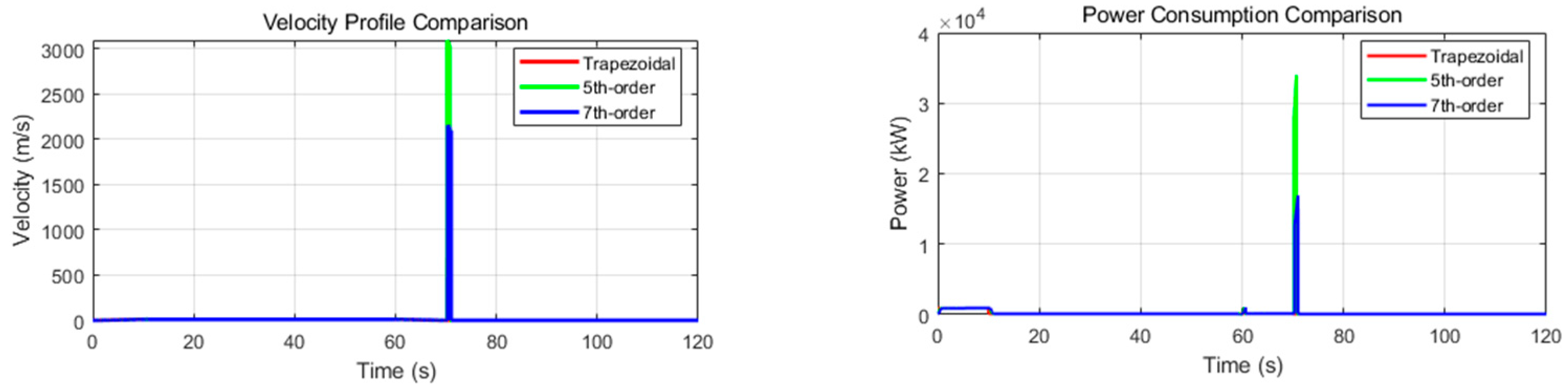

The left

Figure 14 illustrates the velocity profiles of the three algorithms over the same time range. It can be observed that the trapezoidal velocity profile exhibits distinct inflection points during the acceleration and deceleration phases, resulting in more abrupt changes in velocity. In contrast, the 5th-order and 7th-order polynomial curves demonstrate smoother transitions, particularly during the start and stop phases, which helps reduce mechanical shock and vibration.

The right

Figure 14 further compares the system power consumption of the three algorithms during operation. Overall, due to abrupt acceleration changes, the trapezoidal profile leads to significant power fluctuations and higher peak power consumption. In comparison, the 5th-order and 7th-order curves, benefiting from their smoother motion profiles, exhibit more stable power consumption and lower overall energy usage, demonstrating superior energy efficiency, especially over prolonged operation.

6. Conclusions

Technological advances have led to the development of hoisting mechanisms—from steam to modern electric hoisting mechanisms—focusing on large-scale production, design optimization, improvements to the hydraulic braking system, and technological innovation in control and transmission systems. The application of energy storage and maintenance-free technologies has improved the safety and reliability of the system. Market analysis shows that the mine hoist market size is expected to grow significantly due to increasing demand for energy, metallic, and non-metallic minerals. Future research and development will continue to drive the development of mine hoist technology towards higher efficiency, intelligence, and environmental friendliness. Energy Storage and Smart Power Systems, including emergency backup and novel technologies like gravity storage, provide a reliable foundation for safe operation. System Intelligence and Collaborative Control, featuring intelligent speed regulation and advanced braking, transforms the hoist into a truly “smart” system. These technologies synergize for a “1 + 1 > 2” effect. For instance, the seventh-order S-curve generates smooth motion commands. When executed by high-performance drives, this not only minimizes mechanical shock and vibration—extending component life—but also allows associated energy storage systems to efficiently recover regenerative braking energy. According to the S-N fatigue life curve, this stress reduction can potentially double or even more than double the service life of these components. Key assumptions: fatigue is the primary failure mode of components; loads are of constant amplitude; materials are homogeneous and free of initial defects; the linear cumulative damage rule is applied; environmental conditions are stable; and simulated stresses accurately reflect actual stresses. However, practical operating conditions may introduce the following limitations: randomness of load spectra, size effects, surface conditions, mean stress, multiaxial stress states, scatter in fatigue data, and non-uniform reduction in dynamic stresses. Consequently, these predictions should be regarded as theoretical potential, and the actual lifespan extension may vary due to the aforementioned factors. Overall, the system’s energy efficiency improves by 3–8%, which not only lowers operating costs but also directly translates to a proportional 3–8% reduction in Scope 2 (purchased electricity) carbon emissions.