Port-Wine Stains’ Orodental Manifestations and Complications: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration and Validation of Study Protocol

2.2. Question of Study

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection Process and Data Extraction

- -

- General data about the studies (title, main authors, geographical area, DOI, year of publication, study design);

- -

- Population (number of subjects, age/gender distribution);

- -

- Exposure and controls (pathology diagnosed, controls—when available);

- -

- Outcomes (oral, dental, or cranio-facial manifestations reported in studies, complications of treatments).

2.6. Risk of Bias/Quality Assessment

3. Results

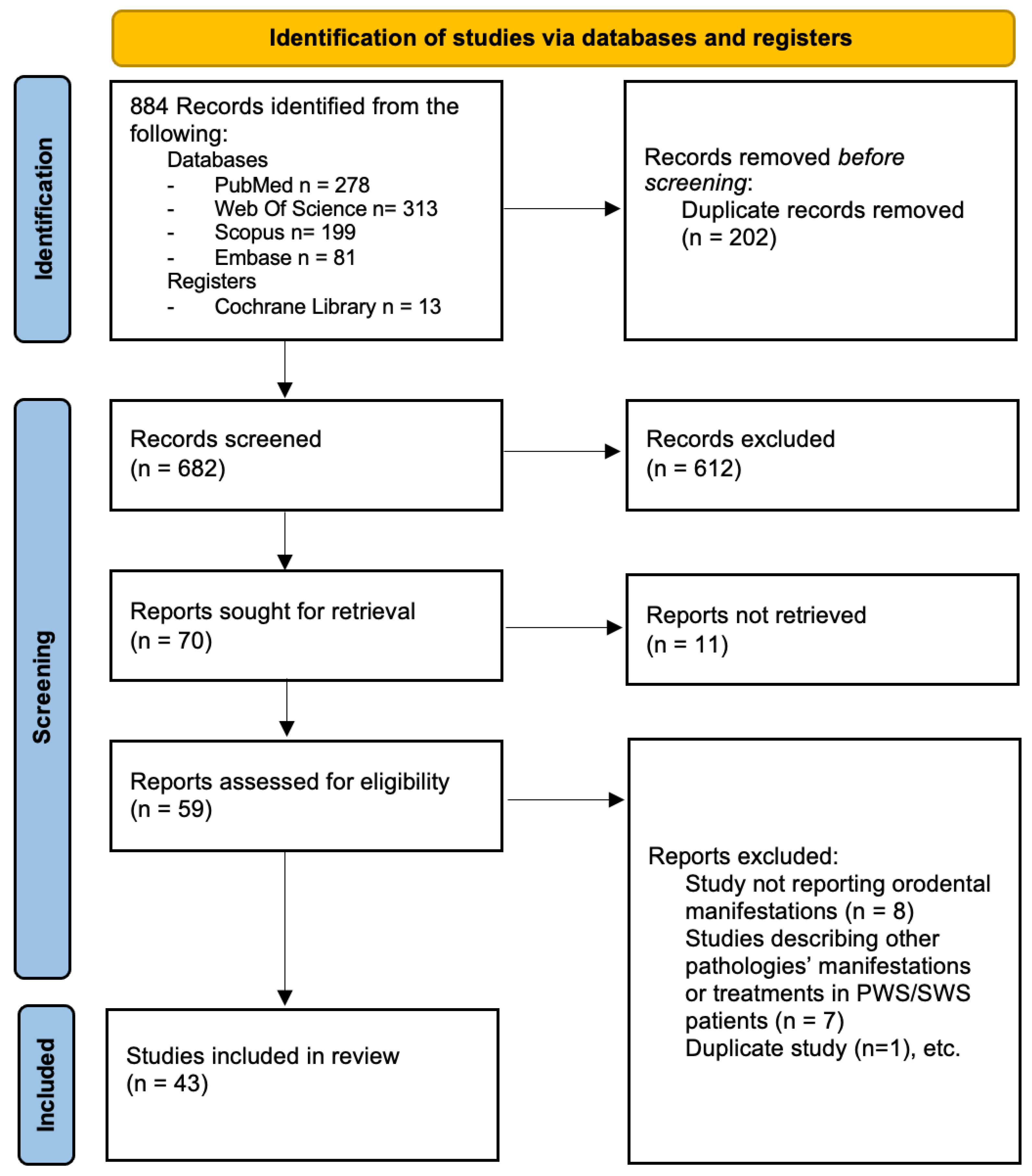

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Description of Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment of the Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X. Pathogenesis of Port-Wine Stains: Directions for Future Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alper, J.C.; Holmes, L.B. The Incidence and Significance of Birthmarks in a Cohort of 4641 Newborns. Pediatr. Dermatol. 1983, 1, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassef, M.; Blei, F.; Adams, D.; Alomari, A.; Baselga, E.; Berenstein, A.; Burrows, P.; Frieden, I.J.; Garzon, M.C.; Lopez-Gutierrez, J.-C.; et al. Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e203–e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo, J.; Gómez-Tellado, M.; López-Gutiérrez, J.C. Vascular Malformations in Childhood. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012, 103, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Hochman, M.; Mihm, M.C.; Nelson, J.S.; Tan, W. The pathogenesis of port wine stain and sturge weber syndrome: Complex interactions between genetic alterations and aberrant MAPK and PI3K activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Hernandez Salas, A.; Fay, A. Trigeminal dermatome distribution in patients with glaucoma and facial port wine stain. Dermatology 2009, 219, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waelchli, R.; Aylett, S.E.; Robinson, K.; Chong, W.K.; Martinez, A.E.; Kinsler, V.A. New vascular classification of port-wine stains: Improving prediction of Sturge-Weber risk. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 171, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, B.; Tan, O.T.; Trainor, S.; Morelli, J.G.; Weston, W.L.; Piepenbrink, J.; Stafford, T.J. Location of Port-Wine Stains and the Likelihood of Ophthalmic and/or Central Nervous System Complications. 1991. Available online: https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/87/3/323/75111 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Dutkiewicz, A.-S.; Ezzedine, K.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Lacour, J.-P.; Barbarot, S.; Vabres, P.; Miquel, J.; Balguerie, X.; Martin, L.; Boralevi, F.; et al. A prospective study of risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome in children with upper facial port-wine stain. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zallmann, M.; Mackay, M.T.; Leventer, R.J.; Ditchfield, M.; Bekhor, P.S.; Su, J.C. Retrospective review of screening for Sturge-Weber syndrome with brain magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography in infants with high-risk port-wine stains. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennedige, A.A.; Quaba, A.A.; Al-Nakib, K. Sturge-Weber syndrome and dermatomal facial port-wine stains: Incidence, association with glaucoma, and pulsed tunable dye laser treatment effectiveness. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M.D.; Tang, H.; Gallione, C.J.; Baugher, J.D.; Frelin, L.P.; Cohen, B.; North, P.E.; Marchuk, D.A.; Comi, A.M.; Pevsner, J. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas-Sohl, K.A.; Vaslow, D.F.; Maria, B.L. Sturge-Weber syndrome: A review. Pediatr. Neurol. 2004, 30, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagtap, S.; Srinivas, G.; Harsha, K.J.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Radhakrishnan, A. Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J. Child Neurol. 2013, 28, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, N.; Wu, Y.; Guo, W. GNAQ R183Q somatic mutation contributes to aberrant arteriovenous specification in Sturge–Weber syndrome through Notch signaling. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Mercado Nadora, D.; Gao, L.; Wang, G.; Mihm, M.C.; Stuart Nelson, J. The somatic GNAQ mutation (R183Q) is primarily located within the blood vessels of port wine stains. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.G.; Sholl, L.M.; Zakka, L.R.; O, T.M.; Liu, C.; Xu, S.; Stanek, E.; Garcia, E.; Jia, Y.; MacConaill, L.E.; et al. Novel genetic mutations in a sporadic port-wine stain. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliner, A.; Fernandez Faith, E.; Blieden, L.; Kelly, K.M.; Metry, D. Port-wine Birthmarks: Update on Diagnosis, Risk Assessment for Sturge-Weber Syndrome, and Management. Pediatr. Rev. 2022, 43, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, M.D.; Bozarth, X.L.; Sidbury, R.; Cooper, A.B.; Perez, F.; Chon, C.; Paras, G.; Amlie-Lefond, C. Forehead location and large segmental pattern of facial port-wine stains predict risk of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Drooge, A.M.; Beek, J.F.; Van Der Veen, J.P.W.; Van Der Horst, C.M.A.M.; Wolkerstorfer, A. Hypertrophy in port-wine stains: Prevalence and patient characteristics in a large patient cohort. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W.; Lyu, D.; Ma, G.; Lin, X. Imaging and Pathological Characteristics of Port-Wine Stain Patients with Tissue Hypertrophy Before Laser Therapy: Retrospective Data. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeron, T.; Salhi, A.; Mazer, J.-M.; Lavogiez, C.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Galliot, C.; Collet-Villette, A.-M.; Labreze, C.; Boon, L.; Hardy, J.-P.; et al. Prognosis and response to laser treatment of early-onset hypertrophic port-wine stains (PWS). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.D.M.; Gailloud, P.; Mccarthy, E.F.; Comi, A.M. Oromaxillofacial Osseous Abnormality in Sturge-Weber Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2006, 27, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pontes, F.S.C.; Neto, N.C.; Da Costa, R.M.B.; Loureiro, A.M.; Do Nascimento, L.S.; Pontes, H.A.R. Periodontal growth in areas of vascular malformation in patients with sturge-weber syndrome: A management protocol. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014, 25, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T.; Frederick Groff, W.; Chan, H.H.; Sakurai, H.; Yamaki, T. Long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser treatment for hypertrophic port-wine stains on the lips. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2009, 11, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedittis, M.; Petruzzi, M.; Pastore, L.; Inchingolo, F.; Serpico, R. Nd:YAG Laser for Gingivectomy in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.B.; Zhao, Y.; Darrow, D.H. Orodental manifestations of facial port-wine stains. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Dhawan, P.; Gaurav, V.; Chandail, K. Alarming skin tatoo with periodontal link: Sturge weber syndrome. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZJ01–ZJ02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, I.S.; Esteves, T.C.; Rocha, A.C.; Chaves, M.; Fabri, G.M.C. Impact of Periodontal Therapy in Patients with Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, ED04–ED06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrati, E.W.; Teresa, M.O.; Binetter, D.; Chung, H.; Waner, M. Surgical Treatment of Head and Neck Port-Wine Stains by Means of a Staged Zonal Approach. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 134, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pithon, M.M.; de Andrade, A.C.D.V.; de Andrade, A.P.D.V.; dos Santos, R.L. Sturge-Weber syndrome in an orthodontic patient. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 140, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Furusho, H.; Matsumura, T.; Nakano, M.; Sawaki, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Akashi, S.; Miyauchi, M.; Mizukawa, N.; Iida, S. Sturge-Weber syndrome with cemento-ossifying fibroma in the maxilla and giant odontoma in the mandible: A case report. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Lonic, D.; Chen, C.; Lo, L.J. Correction of Facial Deformity in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, A.K.; Taber, S.F.; Ball, K.L.; Padwa, B.L.; Mulliken, J.B. Sturge-Weber syndrome: Soft-tissue and skeletal overgrowth. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2009, 20, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.; Kataria, A.; Puri, G.; Konidena, A. Dental considerations of capillary malformation. Indian J. Multidiscip. Dent. 2015, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.C.Q.; Maia, V.N.; Franco, J.B.; De Melo Peres, M.P.S. Emergency Dental Treatment of a Patient with Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, e305–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G.L.; Lima, B.C.; Pinto, L.M.C.; Da Silva, L.M.F.; Cavalcante, M.A.D.A. Computed tomography angiography-assisted embolization of arteriovenous malformation prior to dental extractions in a patient with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2022, 134, e39–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.L.; Letieri, A.D.S.; Lenzi, M.M.; Agostini, M.; Castro, G.F. Oral healthcare management of a child with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis associated with bilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome. Spec. Care Dent. 2019, 39, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagin, O.; Del Neri, N.B.; Battisti, M.d.P.L.; Capelozza, A.L.A.; Santos, P.S.d.S. Periodontal manifestations and ambulatorial management in a patient with Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2012, 23, 1809–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, R.; Saimbi, C.S. Sturge-Weber syndrome: Oral and extra-oral manifestations. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014207663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhi, C.; Anuj, C. Sturge Weber Syndrome: An Unusual Case with Multisystem Manifestations. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2016, 26, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Neerupakam, M.; Reddy, P.S.; Babu, B.A.; Krishna, G.V. Sturge weber syndrome: A case study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZD12–ZD14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Tewari, S.; Tewari, N.; Ghosh, T. Cryotherapy as a conservative treatment modality for gingival enlargement in a patient with Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2017, 6, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Qi, Z.; Jin, X. Surgical correction for patients with port-wine stains and facial asymmetry. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 3307–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaji, P.; Bansal, A.; Choudhury, G.K.; Nayak, R.; Prabhakar, A.K.; Suratkal, N.; Raju, V.; Kamble, S.S. Sturge-Weber Syndrome with Osteohypertrophy of Maxilla. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2013, 2013, 964596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, D.K.; Ng, Z.Y.; Holzer, P.W.; Waner, M.; Cetrulo, C.L.J.; Fay, A. One-Stage Supramaximal Full-Thickness Wedge Resection of Vascular Lip Anomalies. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ Publ. Group 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G.A. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. In Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Systemic Review Methodology, Oxford, England, 3–5 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J. Metaanal. 2017, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.M.P.F.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mopagar, V.P.; Choudhari, S.; Subbaraya, D.K.; Peesapati, S. Sturge-Weber syndrome with pyogenic granuloma. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2013, 4, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.D.; Silva, C.A.B.; De Camargo Moraes, P.; Thomaz, L.A.; Furuse, C.; De Araújo, V.C. Recurrent oral pyogenic granuloma in port-wine stain. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 2356–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deore, G.D.; Gurav, A.N.; Patil, R.; Shete, A.R.; NaikTari, R.S.; Khiste, S.V.; Inamdar, S. Sclerotherapy: A novel bloodless approach to treat recurrent oral pyogenic granuloma associated with port-wine stain. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 28, 1564.e9–1564.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, S.; Shakuntala, G.K.; Rajeshwari, G.A.; Mamata, G.P. Pyogenic Granuloma in a Patient of Sturge-Weber Syndrome with Bilateral Port Wine Stain- A Rare Case Report. J. Krishna Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2014, 3, 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio, A.; Tan, O.T. Laser applications for benign oral lesions. Lasers Surg. Med. 2015, 47, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eivazi, B.; Roessler, M.; Pfützner, W.; Teymoortash, A.; Werner, J.A.; Happle, R. Port-wine stains are more than skin-deep! Expanding the spectrum of extracutaneous manifestations of nevi flammei of the head and neck. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2012, 22, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Ying, H.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, M.; Yang, X. Abnormal tooth maturation associated with port wine stains. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Chung, H.Y.; Cerrati, E.W.; O, T.M.; Waner, M. The Natural History of Soft Tissue Hypertrophy, Bony Hypertrophy, and Nodule Formation in Patients with Untreated Head and Neck Capillary Malformations. Dermatol. Surg. 2015, 41, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary R, I.J.; Sargurunathan, E.A.V.; Venkatesha, R.R.G.; Mohan, K.R.; Fenn, S.M. Port-Wine Stains and Intraoral Hemangiomas: A Case Series. Cureus 2024, 16, e63532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.; Mohan, K.R.; Thangavelu, R.P.; Fenn, S.M.; Appusamy, K. Concurrent Occurrence of Lobular Capillary Haemangioma and Port-Wine Stain: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus J. Med. Sci. 2023, 15, e38642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakonda, B.; Pradeep, K.; Mishra, A.; Reddy, K.; Muralikrishna, T.; Lakshmi, V.; Challa, R. Periodontal Management of Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Case Rep. Dent. 2013, 2013, 517145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.C.; Kwon, J.G.; Jeong, W.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kwon, S.M.; Choi, J.W. Three-dimensional Photogrammetric Analysis of Facial Soft-to-Hard Tissue Ratios After Bimaxillary Surgery in Facial Asymmetry Patients with and Without Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 81, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kado, I.; Ogashira, S.; Ono, S.; Koizumi, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Yoshimi, Y.; Kunimatsu, R.; Ito, S.; Koizumi, Y.; Ogasawara, T.; et al. Surgical Orthodontic Treatment for Skeletal Maxillary Protrusion in Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus J. Med. Sci. 2024, 16, e59964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, S.; Iijima, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Kaneko, T.; Horie, N.; Shimoyama, T. Tooth extraction with Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2017, 29, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, N.; Bhaskar, N. Sturge-Weber syndrome: A case report. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2010, 1, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manivannan, N.; Gokulanathan, S.; Ahathya, R.; Gubernath Daniel, R.; Shanmugasundaram. Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012, 4, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Akhade, S.N.; Chandak, R.; Shaikh, F. Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int. J. Sci. Study 2015, 2, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram Mohan, K.; Fenn, S.M.; Pethagounder Thangavelu, R. Concurrent Occurrence of Port-Wine Stain and Glaucoma in Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e37451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhansali, R.S.; Yeltiwar, R.K.; Agrawal, A.A. Periodontal Management of Gingival Enlargement Associated with Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S. Sturge-Weber syndrome: A case report. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2008, 26, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.E.C.; Pereira Neto, J.S.; Graner, E.; Lopes, M.A. Sturge-Weber syndrome in a 6-year-old girl. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2005, 15, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Rani, K.; Indumathy, P.; Rajashree, D. Gingival overgrowth associated with port-wine stains: A case report of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Dr. NTR Univ. Health Sci. 2014, 3, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwani, O.A.; Patra, P.C.; Ahmad, S.A.; Hasan, S. Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Report of a Rare Case. Cureus 2023, 15, e51110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprabha, B.S.; Baliga, M. Total oral rehabilitation in a patient with portwine stains. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2005, 23, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronemus, R.G.; Ashinoff, R. The Medical Necessity of Evaluation and Treatment of Port-Wine Stains. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1991, 17, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapman, M.H.; Yao, J.F. Thickening and nodules in port-wine stains. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 44, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.; Bernstein, L.J.; Belkin, D.A.; Ghalili, S.; Geronemus, R.G. Pulsed Dye Laser Treatment of Port-Wine Stains in Infancy Without the Need for General Anesthesia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederhandler, M.H.; Pomerantz, H.; Orbuch, D.; Geronemus, R.G. Treating pediatric port-wine stains in aesthetics. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 40, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightman, L.A.; Geronemus, R.G.; Reddy, K.K. Laser treatment of port-wine stains. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Minkis, K.; Geronemus, R.G.; Hale, E.K. Port wine stain progression: A potential consequence of delayed and inadequate treatment? Lasers Surg. Med. 2009, 41, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinkara, G.; Langbroek, G.B.; van der Horst, C.M.A.M.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Horbach, S.E.R.; Ubbink, D.T. Therapeutic Strategies for Untreated Capillary Malformations of the Head and Neck Region: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, S.; Ball, K.L.; Burkhart, C.; Eichenfield, L.; Faith, E.F.; Frieden, I.J.; Geronemus, R.; Gupta, D.; Krakowski, A.C.; Levy, M.L.; et al. Consensus Statement for the Management and Treatment of Port-Wine Birthmarks in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Horst, C.M.A.M.; De Borgie, C.A.J.M.; Knopper, J.L.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. Psychosocial adjustment of children and adults with port wine stains. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1997, 50, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Shao, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, N.; Liu, J.; Li, Z. Influence of Port-wine Stains on Quality of Life of Children and Their Parents. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanitphakdeedecha, R.; Sudhipongpracha, T.; Ng, J.N.C.; Yan, C.; Jantarakolica, T. Self-stigma and psychosocial burden of patients with port-wine stain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 2203–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masnari, O.; Schiestl, C.; Rössler, J.; Gütlein, S.K.; Neuhaus, K.; Weibel, L.; Meuli, M.; Landolt, M.A. Stigmatization predicts psychological adjustment and quality of life in children and adolescents with a facial difference. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, S.L.; Grey, K.R.; Korta, D.Z.; Kelly, K.M. Quality of life in adults with facial port-wine stains. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 76, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Yao, X.-H.; Zhang, L.-F.; Lv, H.; Zhang, S.-P.; Hu, B. Analysis of quality of life and influencing factors in 197 Chinese patients with port-wine stains. Medicine 2017, 96, e9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Baghaie, H.; Lalloo, R.; Siskind, D.; Johnson, N.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and severe mental illness. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Sawyer, E.; Siskind, D.; Lalloo, R. The oral health of people with anxiety and depressive disorders—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, A.; Cakmak, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Cebi, T.; Gurgan, C. Relationship Between Psychological Factors and Oral Health Status and Behaviours. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2015, 13, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgner, S.; Dreger, M.; Henschke, C. Reasons for (not) choosing dental treatments—A qualitative study based on patients’ perspective. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settineri, S.; Rizzo, A.; Liotta, M.; Mento, C. Clinical Psychology of Oral Health: The Link Between Teeth and Emotions. Sage Open 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, T.; Kelly, A.; Randall, C.L.; Tranby, E.; Franstve-Hawley, J. Association Between Mental Health and Oral Health Status and Care Utilization. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 732882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Silva, C.O.; Tatakis, D.N. Plaque-induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S44–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrup, P.; Plemons, J.; Meyle, J. Non–plaque-induced gingival diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S28–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altayeb, W.; Hamadah, O.; Alhaffar, B.A.; Abdullah, A.; Romanos, G. Gingival depigmentation with diode and Er,Cr:YSGG laser: Evaluating re-pigmentation rate and patient perceptions. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 5351–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, P.; Daing, A.; Azam, I.; Miglani, R.; Bhardwaj, A. Impact of altered gingival characteristics on smile esthetics: Laypersons’ perspectives by Q sort methodology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 82–90.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.H.; Yang, W.S.; Nahm, D.S. Effects of upper lip closing force on craniofacial structures. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentim, A.; Furlan, R.; Amaral, M.; Martins, F. Can Orofacial Structures Affect Tooth Morphology? In Human Teeth—Key Skills and Clinical Illustrations; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/68734 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Priede, D.; Roze, B.; Parshutin, S.; Arkliņa, D.; Pircher, J.; Vaska, I.; Folkmanis, V.; Tzivian, L.; Henkuzena, I. Association between malocclusion and orofacial myofunctional disorders of pre-school children in Latvia. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raath, M.I.; Bambach, C.A.; Dijksman, L.M.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Heger, M. Prospective analysis of the port-wine stain patient population in the Netherlands in light of novel treatment modalities. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2018, 20, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, P.H.L.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; van der Horst, C.M.A.M.; Gijsbers, G.H.M.; van Gemert, M.J.C. Characterization of Portwine Stain Disfigurement. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Author | Year | Study Type | Geographic Area | Sample Size | Orodental Manifestations | Treatments | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frigerio et al. [55] | 2015 | Retrospective study | USA | 26–7 with PWSs (port-wine stains) | Gingival hypertrophy, gingival bleeding, gingival staining, and lip hypertrophy | Laser photocoagulation of vascular lesions | Recurrence of PWSs in some cases |

| Eivazi et al. [56] | 2012 | Retrospective study | Germany | 9 | Lip hypertrophy, gingival bleeding, dysphonia, dysphagia parotidean inflammation, tongue hypertrophy, gingival staining, facial asymmetry due to soft tissue involvement, and ulcerations | None | - |

| Liu et al. [57] | 2024 | Retrospective study | China | 21 | Gingival hypertrophy, early tooth eruption, stained gingiva, and malocclusion, | None | Malocclusion |

| Zhou et al. [44] | 2020 | Retrospective study | China | 2 | Buccal hypertrophy, maxillary hypertrophy, malocclusion, occlusal canting, lip hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, gingival staining, excessive gingival display, mandibular hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, and excessive gingival display | Osteotomies and soft tissue reductive surgery | None |

| Dowling et al. [27] | 2012 | Cross-sectional study | USA | 30 | Lip hypertrophy, stained gingiva, gingival bleeding, gingivitis, malocclusion, tooth spacing, maxillary or mandibular hypertrophy, gingival hypertrophy, tongue hypertrophy, prolonged inflammation after dental interventions, and excessive bleeding | None | Rare haemorrhage after dental procedures |

| Lee et al. [58] | 2015 | Retrospective study | South Korea | 160 | Gingival hypertrophy, lip hypertrophy, buccal hypertrophy, maxillary and mandibular hypertrophy, tongue hypertrophy, and facial asymmetry | None | None |

| De Castro et al. [46] | 2017 | Retrospective study | USA | 18–6 with PWS | Lip hypertrophy and ulcerations | Full-thickness wedge resection for lip size reduction | None |

| Deore et al. [53] | 2014 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival staining and recurrent pyogenic granuloma | Sclerotherapy with sodium tetradecyl sulfate, scaling, and root planing | None |

| Mary R et al. [59] | 2024 | Case series | India | 2 (1 with PWS) | Gingival staining | Oral prophylaxis | None |

| Patil et al. [35] | 2015 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival staining | None | Risk of excessive bleeding on probing |

| Priya et al. [60] | 2023 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival staining | Excision of gingival growth | Bleeding tendency and discomfort |

| Main Author | Year Published | Study Type | Geographic Area | Sample Size | Orodental Manifestations | Treatments | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greene et al. [34] | 2009 | Retrospective study | USA | 155 | Lip hypertrophy, buccal hypertrophy, maxillary and mandibular hypertrophy, and facial asymmetries | Surgical corrections of soft and hard tissues hypertrophy | Persistent facial asymmetry |

| Kalakonda et al. [61] | 2013 | Case series | India | 3 | Gingival hypertrophy, gingival bleeding, gingivitis, lip hypertrophy, and gingival staining | Scaling, root planing, gingivectomy, and laser gingivectomy | None |

| Kim et al. [62] | 2018 | Retrospective study | South Korea | 10–5 with SWS (Sturge–Weber syndrome) | Malocclusion, occlusal canting, facial asymmetry, maxillary hypertrophy, drooping labial commissure on affected side, lip hypertrophy, and buccal hypertrophy | Osteotomies, soft tissue reductive surgery, and plastic surgery | None |

| Yamaguchi et al. [33] | 2016 | Case series | Taiwan | 2 | Maxillary hypertrophy, malocclusion, lip hypertrophy, buccal hypertrophy, occlusal canting, excessive gingival display, and excessive bleeding after dental interventions | Osteotomies and soft tissue reductive surgery | None |

| Babaji et al. [45] | 2013 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, maxillary hypertrophy, gingival staining, and malocclusion | Maxillectomy and dental extractions | None |

| Arunkumar et al. [54] | 2014 | Case report | India | 1 | Pyogenic granuloma, gingival hypertrophy, lip hypertrophy, and gingival staining | Pyogenic granuloma excision | Difficulty in mastication, bleeding, and recurrent swelling |

| De Oliveira et al. [36] | 2015 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Gingivitis | Endodontic treatment with non-surgical approach | None |

| De Oliveira et al. [29] | 2019 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Facial asymmetry, lip hypertrophy, and gingival hypertrophy | Scaling, root planing, and laser therapy | None |

| Kado et al. [63] | 2024 | Case report | Japan | 1 | Lip hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, gingival hypertrophy, and lip incompetence | Sagittal split ramus osteotomy and orthodontic treatment | None |

| Hino et al. [64] | 2017 | Case report | Japan | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, malocclusion, and gingival staining | Tooth extraction with sedation | None |

| Gill and Bhaskar [65] | 2010 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, gingival bleeding, and gingival staining | Tooth extraction | None |

| Dutt et al. [28] | 2016 | Case report | India | 1 | Facial asymmetry, gingival staining, malocclusion, gingival hypertrophy, and gingival bleeding | Scaling, root planing, and gingivectomy | None |

| Manivannan et al. [66] | 2012 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival bleeding, gingival hypertrophy, gingival staining, and malocclusion | Scaling, root planing, and gingivectomy | Gingival bleeding |

| Kulkarni et al. [67] | 2015 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival staining, maxillary hypertrophy, gingival hypertrophy, and lip hypertrophy | Gingivectomy, extractions, and prophylaxis | None |

| Pagin et al. [39] | 2012 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, gingival staining, and gingival bleeding | Scaling, root planing, and chlorhexidine mouthwash | None |

| Mopagar et al. [51] | 2013 | Case report | India | 1 | Pyogenic granuloma, gingival bleeding, malocclusion, facial asymmetry, and gingival staining | Scaling and laser surgery | None |

| Mohan et al. [68] | 2023 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival staining and tongue hypertrophy | None | None |

| Nidhi and Anuj [41] | 2016 | Case report | India | 1 | Facial asymmetry, lip hypertrophy, gingival hypertrophy, gingival staining, and malocclusion | Scaling and root planing | None |

| Neerupakam et al. [42] | 2017 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, pyogenic granuloma, and gingival staining | Surgical excision of pyogenic granuloma, scaling, root planning, and gingivectomy | Recurrence of pyogenic granuloma |

| Martins et al. [38] | 2019 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Maxillary hypertrophy, malocclusion, gingival staining, lip incompetence, and lip hypertrophy | Minimally invasive restorative treatment | None |

| Bhansali et al. [69] | 2008 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, lip hypertrophy, lip incompetence, gingival staining, and maxillary hypertrophy | Scaling, root planning, tooth extraction, and gingivectomy | Recurrent gingival hypertrophy |

| Lin et al. [23] | 2006 | Case report | USA | 1 | Lip hypertrophy, maxillary hypertrophy, and malocclusion | Maxillectomy and reconstruction | Difficulty in mastication and breathing issues |

| Mukhopadhyay [70] | 2008 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, gingival staining, malocclusion, and gingival bleeding | None | Bleeding and difficulty in speech |

| Perez et al. [71] | 2005 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, malocclusion, lip hypertrophy, and lip incompetence | Prophylaxis and orthodontic treatment | None |

| Pithon et al. [31] | 2011 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, early tooth eruption, malocclusion, and occlusal canting | None | None |

| Pontes et al. [24] | 2014 | Case report | Brazil | 1 | Bone resorption, lip hypertrophy, and gingival hypertrophy | Flap surgery, gingivectomy, osteotomy, osteoplasty, and extraction of teeth | None |

| Reddy et al. [72] | 2014 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, lip hypertrophy, lip incompetence, and alveolar bone loss | Scaling, root planning, prophylaxis, and gingivectomy | None |

| Sherwani et al. [73] | 2023 | Case report | India | 1 | Lip hypertrophy, gingival hypertrophy, mucosal staining, and gingival bleeding | Scaling, root planning, and prophylaxis | None |

| Suprabha and Baliga [74] | 2005 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, facial asymmetry, lip hypertrophy, malocclusion, and mucosal staining | Oral prophylaxis | None |

| Tripathi et al. [40] | 2015 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy and alveolar bone loss | Oral prophylaxis | None |

| Yadav et al. [43] | 2017 | Case report | India | 1 | Gingival hypertrophy, mucosal staining, gingival bleeding, and facial asymmetry | Oral prophylaxis | None |

| De Benedittis [26] | 2007 | Case report | Italy | 1 | Soft tissue hypertrophy, gingival hypertrophy, lower lip hypertrophy, macroglossia, and gingivitis | Laser gingivectomy | None |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | NOS Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Definition | Representativeness | Controls | Control Definition | Ascertainment | Methods | Non-Response Rate | |||

| Frigerio et al. [55] | * | - | * | - | * | * | * | - | 5/9 |

| Eivazi et al. [56] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | - | 8/9 |

| Liu et al. [57] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | - | 8/9 |

| Zhou et al. [44] | * | * | - | - | * | * | - | - | 4/9 |

| Dowling et al. [27] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Lee et al. [58] | * | * | - | - | ** | * | - | - | 5/9 |

| De Castro et al. [46] | * | - | * | - | * | * | * | * | 6/9 |

| Greene et al. [34] | * | * | * | - | ** | * | - | * | 7/9 |

| Kalakonda et al. [61] | * | * | - | - | - | * | - | - | 3/9 |

| Kim et al. [62] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | - | 8/9 |

| Yamaguchi et al. [33] | * | * | - | - | - | * | - | - | 3/9 |

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were Patient’s Demographic Characteristics Clearly Described? | Was the Patient’s History Clearly Described and Presented as a Timeline? | Was the Current Clinical Condition of the Patient on Presentation Clearly Described? | Were Diagnostic Tests or Assessment Methods and the Results Clearly Described? | Was the Intervention(s) or Treatment Procedure(s) Clearly Described? | Was the Post-intervention Clinical Condition Clearly Described? | Were Adverse Events (Harms) or Unanticipated Events Identified and Described? | Does the Case Report Provide Takeaway Lessons? | |

| Deore et al. [53] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Mary R et al. [59] | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Patil et al. [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | Unclear |

| Priya et al. [60] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Babaji et al. [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Arunkumar et al. [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| De Oliveira et al. [36] | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| De Oliveira et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Kado et al. [63] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hino et al. [64] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Gill and Bhaskar [65] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dutt et al. [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Manivannan et al. [66] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Kulkarni et al. [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Pagin et al. [39] | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear |

| Mopagar et al. [51] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mohan et al. [68] | No | No | Yes | Unclear | NA | NA | NA | No |

| Nidhi and Anuj [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neerupakam et al. [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Martins et al. [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bhansali et al. [69] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lin et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Mukhopadhyay [70] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | Yes |

| Perez et al. [71] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pithon et al. [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | Yes |

| Pontes et al. [24] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Reddy et al. [72] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sherwani et al. [73] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Suprabha and Baliga [74] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tripathi et al. [40] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear |

| Yadav et al. [43] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| De Benedittis [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kui, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Buduru, S.; Condor, A.-M.; Chira, D.; Condor, D.C.; Lucaciu, O.P. Port-Wine Stains’ Orodental Manifestations and Complications: A Systematic Review. Oral 2025, 5, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010016

Kui A, Negucioiu M, Buduru S, Condor A-M, Chira D, Condor DC, Lucaciu OP. Port-Wine Stains’ Orodental Manifestations and Complications: A Systematic Review. Oral. 2025; 5(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleKui, Andreea, Marius Negucioiu, Smaranda Buduru, Ana-Maria Condor, Daria Chira, Daniela Cornelia Condor, and Ondine Patricia Lucaciu. 2025. "Port-Wine Stains’ Orodental Manifestations and Complications: A Systematic Review" Oral 5, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010016

APA StyleKui, A., Negucioiu, M., Buduru, S., Condor, A.-M., Chira, D., Condor, D. C., & Lucaciu, O. P. (2025). Port-Wine Stains’ Orodental Manifestations and Complications: A Systematic Review. Oral, 5(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010016