No Room for Clio? Digital Approaches to Historical Awareness and Cultural Heritage Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. History Education and Youth Engagement

2.2. Active Methodologies in History Teaching

2.3. Identity, Globalization, and the Loss of Historical Bonds

2.4. Humanities, Tourism and Cultural Sustainability

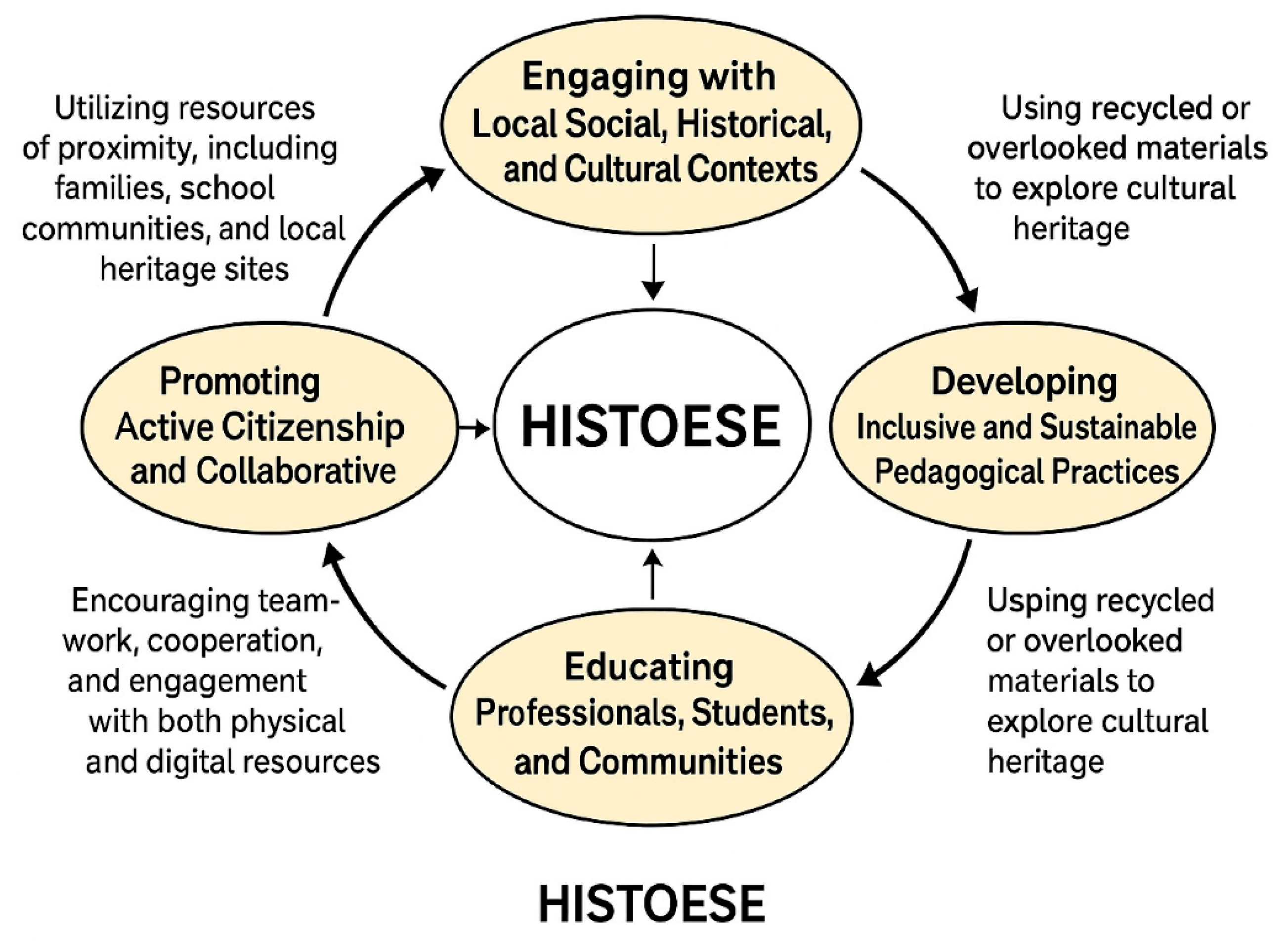

2.5. Towards an Integrated Model: HISTOESE as a Framework for Historical Literacy

3. Methodology

- A questionnaire and survey applied to 65 students enrolled in Tourism (undergraduate) and Education (master’s programmes for teaching qualification), designed to assess levels of historical awareness, cultural consumption habits, and perceptions of heritage.

- A co-creation project conducted with six students from Viana do Castelo and Coimbra polytechnics, using the Demola platform, which engaged participants in collaborative design thinking workshops aimed at developing innovative proposals to motivate young people to reconnect with history and cultural identity.

- Qualitative techniques such as biographical narratives, reflective journals (field notes and logbooks), and document analysis, which enabled a deeper understanding of individual and collective perspectives.

- School of Technology and Management (ESTG)—Tourism undergraduate students.

- School of Education (ESE)—Master’s students enrolled in teaching qualification programmes.

- Tourism (undergraduate): 58% (n ≈ 38);

- Education (Master’s–teaching qualification): 42% (n ≈ 27);

- Gender: Female 68%; Male 32%;

- Age groups: 18–22 (47%); 23–27 (35%); 28+ (18%).

3.1. Research Questions

- To what extent do higher education students demonstrate historical awareness and cultural identity in their personal and professional lives?

- How do young people perceive the role of history and heritage in their education and cultural consumption habits?

- What is the potential of active pedagogical methodologies—particularly the Demola co-creation model and design thinking—to foster meaningful historical learning and heritage engagement?

- How can digital tools, including artificial intelligence, support the development of historical literacy and heritage education in tourism and teacher training contexts?

3.2. Hybrid and Interdisciplinary Design

- Students in Tourism programmes (undergraduate), expected to develop skills in interpreting and communicating heritage in professional contexts.

- Students in Education programmes (master’s level), which will be future teachers responsible for fostering historical literacy and cultural identity from early childhood to basic education.

3.3. Instruments and Data Collection

- Questionnaire and survey (n = 65)

- 2.

- Co-creation (Demola-style) pilot workshops (n = 6)—The pilot followed a structured three-stage design thinking protocol adapted for a semester-long engagement:

- -

- Stage 1—Framing & Ideation (2 sessions, 3 h each): problem framing; stakeholder mapping; brainstorming.

- -

- Stage 2—Prototyping (3 sessions, 3 h each): rapid prototyping with digital tools (Miro boards, low-fidelity interactive prototypes), design of storyboards for AR experiences, and initial mock-ups of gamified flows.

- -

- Stage 3—Testing & Reflection (1 session, 3 h): user-feedback simulation, public presentation, and reflective debrief.

- -

- Creativity and novelty of solution (rubric: 1–4);

- -

- Pedagogical relevance to heritage education (rubric: 1–4);

- -

- Feasibility/technical viability (rubric: 1–4).

- 3.

- Degree of student ownership and collaboration (observational scale 1–4). Qualitative sources—biographical narratives (solicited short reflection essays), reflective journals by participants, and researcher field notes. These were coded for themes: family influence, school experience, digital affordances, motivation, and identity.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

3.5. Pedagogical Experimentation and Active Learning Framework

- Encourage student participation as co-authors of heritage narratives.

- Explore digital storytelling, gamification, and virtual simulations as tools for engaging with history.

- Experiment with AI-driven analysis of historical sources and student feedback, as a way to connect digital innovation with history didactics.

- Foster transversal competences such as collaboration, creativity, and cultural interpretation, in line with the OECD Learning Compass 2030 (OECD, 2019a, 2019b) and the UNESCO frameworks on cultural heritage education (UNESCO, 2015, 2021).

4. Findings

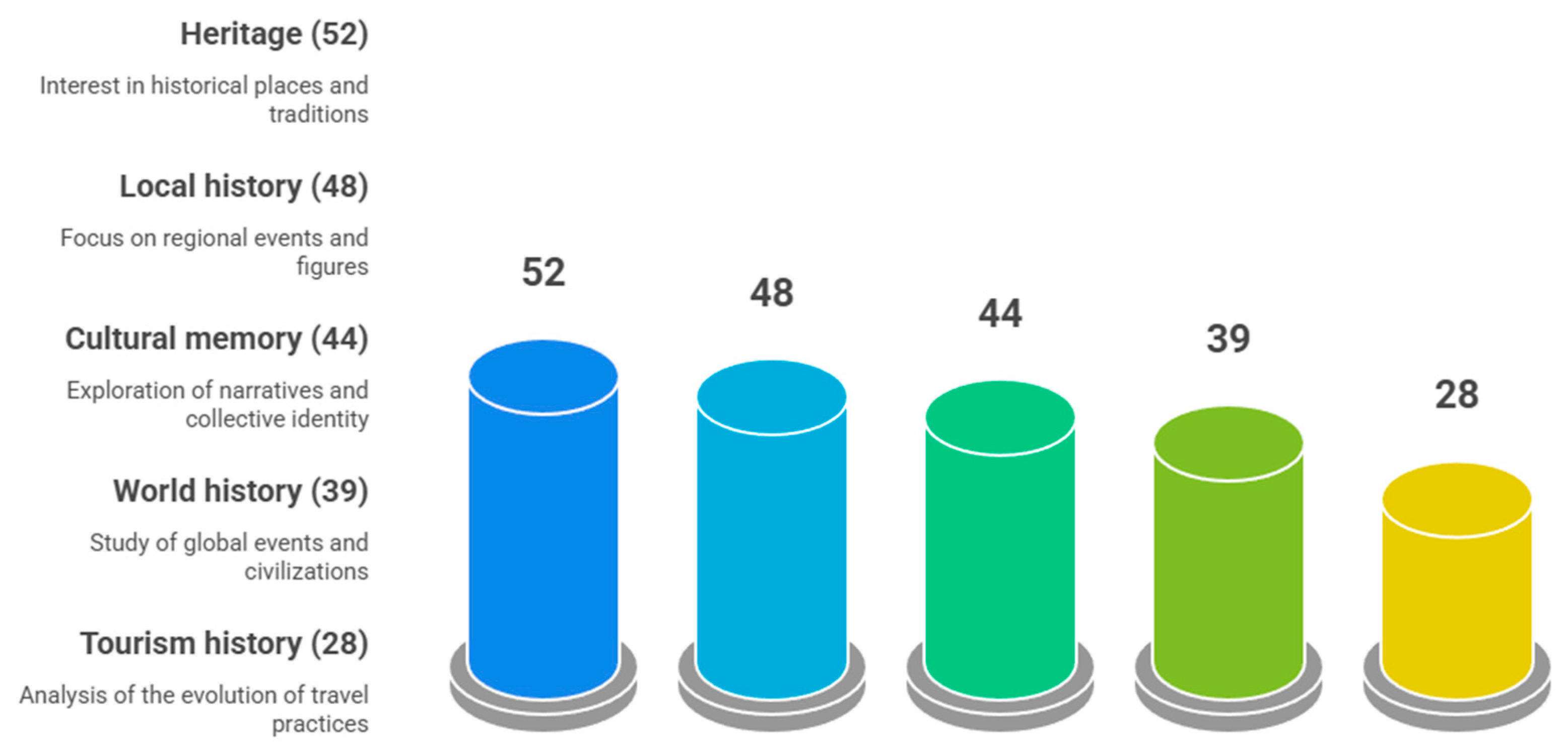

4.1. Survey Results: Historical Awareness and Cultural Consumption

4.2. Qualitative Insights: Narratives and Cultural Identity

- Student A (Tourism, 21): “I’ve always liked history, but at school it felt distant—just dates and names. It was only when I visited local museums that I realized how our past is part of our everyday life.”

- Student B (Education, 25): “We learn about the world’s history, but not enough about our own towns or families. That makes it harder to feel connected to heritage.”

- Student C (Tourism, 23): “When we used digital tools in the workshop, it became more engaging. I could see history as something to explore, not just memorize.”

- Student D (Education, 26): “Heritage is about identity, but if schools don’t make space for it, young people grow up without a sense of belonging. That’s what needs to change.”

4.3. The Demola Co-Creation Project: Active and Digital Pedagogies

- -

- Gamification of heritage learning through digital quizzes and interactive challenges linked to local cultural sites.

- -

- Storytelling platforms where students could narrate their own cultural experiences and link them to broader historical contexts.

- -

- Augmented reality applications to enhance visits to museums and historical landmarks, enabling immersive experiences.

- -

- AI-supported tools for personalizing heritage learning, such as adaptive quizzes or intelligent recommendation systems for cultural activities.

4.4. Intentionality in Pedagogical and Didactic Methodologies: Towards a Pedagogy of Memory

- Gamification: prototypes included location-based quizzes for local heritage routes tied to short narratives; feasibility: medium (requires app development and content curation). Pedagogical value: high—fosters exploration and social competition.

- Storytelling platform: low-tech platform to capture oral histories collected by students; feasibility: high (web platform); pedagogical value: strong for identity building and intergenerational exchange.

- Augmented Reality (AR) applications: AR overlays reconstructing lost features of monuments to enhance on-site interpretation; feasibility: medium-high (requires 3D assets); pedagogical value: strong for contextualisation.

- Digital-personalisation tools: adaptive quizzes and recommendation engines to align heritage activities with interests; feasibility: medium; pedagogical value: supports differentiated pathways.

5. Discussion

5.1. International Perspectives on Co-Creation and Heritage Education

5.2. Sustainability of the Demola Approach in Historical and Heritage Education

5.3. Policy Frameworks and Empirical Convergence

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- Comparative, cross-institutional studies, capturing cultural and educational diversity.

- Longitudinal research, measuring cognitive gains in historical thinking using validated instruments.

- Enhanced use of AI for personalized heritage learning and data analysis.

- Stronger partnerships with museums, heritage institutions, and tourism operators, to co-develop scalable interventions.

5.5. Towards a Pedagogy of Memory in the Digital Age

- Active and participatory methods, such as co-creation and design thinking, to re-engage students with history.

- Digital innovation, including gamification, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence, to provide personalized and immersive learning.

- Institutional and policy support, from both international organizations and national bodies such as CNIPES, to ensure sustainability and integration.

5.6. National Frameworks and the Role of CNIPES

6. Conclusions

6.1. Answering the Research Questions

6.2. Broader Implications

6.3. Towards a Pedagogy of Memory

- Historical literacy and critical reasoning;

- Participatory and community engagement;

- Digital innovation;

- Cultural sustainability.

6.4. Final Considerations

- Stronger curricular integration of heritage education;

- Institutional support at national and international levels;

- Continued experimentation with AI and immersive tools;

- Longitudinal and comparative studies to measure long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| PBL | Problem-based learning |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization |

References

- Airey, D. (2016). Tourism education: Past, present and future. Turisticko Poslovanje, 17, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airey, D., & Tribe, J. (Eds.). (2005). An international handbook of tourism education. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisiah, A., Suhartono, S., & Sumarno, S. (2016). The measurement model of historical awareness. Research and Evaluation in Education, 2(2), 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D. S. d., e Abreu, F. B., & Boavida-Portugal, I. (2025). Digital twins in tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 47, 101133. [Google Scholar]

- Amante, R., & Fernandes, R. (2022). Learning based on co-creation processes: A glimpse of the (Demola) pedagogical innovation training course at IPV. In Proceedings of the 17th European conference on innovation and entrepreneurship (pp. 15–21). Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Brydon-Miller, M., Kral, M., & Ortiz Aragón, A. (2020). Participatory action research: International perspectives and practices. International Review of Qualitative Research, 13(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A., Teixeira, S., Olim, L., Campanella, S., & Costa, T. (2021). Pedagogical innovation in higher education and active learning methodologies—A case study. Education + Training, 63(2), 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá-Pérez, D., Rask, M., & De-Miguel-Molina, M. (2020). The Demola model as a public policy tool boosting collaboration in innovation: A comparative study between Finland and Spain. Technology in Society, 63, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claravall, E. B., & Irey, R. (2022). Fostering historical thinking: The use of document based instruction for students with learning differences. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 46(3), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNIPES—Conselho Nacional da Inovação Pedagógica no Ensino Superior. (2024). Decreto regulamentar n.º 4/2024. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-regulamentar/4-2024-895287961 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Costa, J., Gonçalves, V., & Ferro-Lebres, V. (2022). Processos de cocriação e colaboração no projeto Demola através da plataforma Miro. In V. Gonçalves, A. García-Valcárcel, J. A. Moreira, & M. R. Patrício (Eds.), ieTIC2022: Livro de atas (pp. 83–99). Instituto Politécnico de Bragança. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10198/26307 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Council of Europe. (2005). Convention on the value of cultural heritage for society (Faro Convention). Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Council of Europe. (2016). Presentation of the project "competences for democratic culture". Council of Europe Publishing. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/education/competences-for-democratic-culture (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Demola Global. (2020). Demola co-creation model: From local innovation experiment to global platform. Demola Global. Available online: https://www.demola.net (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Doussot, S. (2019). Case studies in history education: Thinking action research through an epistemological framework. Educational Action Research, 28(2), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D., Airey, D., & Gross, M. J. (2012). The nature and purpose of tourism higher education: A review of curriculum content and learning outcomes. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 12(4), 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J. W., & Maschi, T. (2016). Content analysis. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2018). Innovation in cultural heritage research: For an integrated European research policy. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council. (2017). Competences for democratic culture: Living together as equals in culturally diverse democratic societies. Council of Europe Education Department. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/education/-/competences-for-democratic-culture (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Feekery, A. (2023). The 7 C’s framework for participatory action research: Inducting novice participant-researchers. Educational Action Research, 32(3), 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A., & Andrade, C. (2023). A avaliação e a educação em turismo: Perspetivas no ensino superior português. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 39, 231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villarán, M., Guereño-Omil, B., & Ageitos, M. C. (2024). Embedding sustainability in tourism education: Bridging curriculum Gaps for a sustainable future. Sustainability, 16(21), 9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidgeon, P. R. (2010). Tourism education and curriculum design: A time for consolidation and review? Tourism Management, 31(6), 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M., Matias, R., Alves, V., Bastos, N., Duarte, R. P., Ferreira, B., & Cunha, C. (2021). Professional development for higher education teaching staff: An experience of peer learning in a Portuguese polytechnic. In L. G. Chova, A. L. Martínez, & I. C. Torres (Eds.), INTED2021 proceedings (pp. 6356–6361). IATED. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A. M. (2018). Tourism education: Challenges and innovations. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, T., & Wald, N. (2018). Curriculum, teaching and powerful knowledge. Higher Education, 76(4), 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2005). Participatory action research: Communicative action and the public sphere. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 559–603). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. (2023, June 25–30). Memorialization through metaverse: New technologies for heritage education. 29th CIPA Symposium—Documenting, Understanding, Preserving Cultural Heritage: Humanities and Digital Technologies for Shaping the Future, Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, T., & Durall, E. (2014). Design thinking and collaborative learning. Comunicar, 21(42), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, S. (2008). Thinking historically: Educating students for the twenty-first century. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L., & Pérez, Y. (2021). Cultural tourism and heritage education in the Portuguese way of St. James. In C. Bevilacqua, F. Calabrò, & L. Della Spina (Eds.), New metropolitan perspectives (Smart innovation, systems and technologies, Vol. 178). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B. D., Wang, T., Mannuru, N. R., & Nie, B. (2023). Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News, 40(3), 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricato, D., Aquino, J., & Johanesson, G. (2025). Pedagogical practices in tourism higher education: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Sustainable Tourism, 4, 1720759. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, C., Agostino, D., & Simoni, L. (2022). Co-creating history: The case of WORTHY as a virtual collaborative museum. Journal of Museum Education, 47(3), 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G. M. (2024, May 8–10). No room for clio: Historical and cultural awareness of younger people in liquid times. INVTUR Conference 2024 (pp. 545–548), Aveiro, Portugal. Available online: https://proa.ua.pt/index.php/invtur/article/view/34030 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Marques, G. M. (2025a). Didactic and pedagogical aspects of tourism training programs in Portugal: Conceptual analysis of study plans. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G. M. (2025b). Heritage education, sustainability and community resilience: The HISTOESE PBL model. Sustainability, 17(21), 9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Garcia, E., Coll-Ramis, D., & Horrach-Rossello, R. (2024). Tourism education research: A bibliometric review of emerging themes. Annals of Tourism Research, 101, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2010). You and your action research project (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napkin AI. (2024). Napkin AI [Artificial intelligence–assisted visualisation platform]. Available online: https://www.napkin.ai (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- OECD. (2019a). Future of education and skills 2030: OECD learning compass 2030. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/projects/future-of-education-and-skills-2030.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- OECD. (2019b). The OECD Learning Compass 2030: A framework for education for the future. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. Available online: https://chat.openai.com/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Postareff, L., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Nevgi, A. (2007). The effect of pedagogical training on teaching in higher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(5), 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reche, M., & Janissek-Muniz, R. (2018). Inteligência estratégica e design thinking. Future Studies Research Journal, 10(1), 82–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M.-B. (2015). Conceptualising customer-to-customer co-creation in socially dense tourism contexts. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(4), 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusvitaningrum, Y., Agung, S. L., & Sudiyanto, S. (2018). Strengthening students’ historical awareness in history learning in high school through inquiry method. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 5(5), 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L. (2021). Relationship between students’ historical awareness and their appreciation of local cultural heritage. International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education Research, 2(6), 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, P. (2006). Benchmarks of historical thinking: A framework for assessment in Canada. Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. Available online: https://historicalthinking.ca (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Smith, M. K. (2009). Issues in cultural tourism studies. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U., & Gretzel, U. (2020). Tourism 4.0 technologies and tourist experiences. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, M., Sariyatun, N., & Ardianto, D. T. (2020). The level of students’ historical awareness. International Journal of Education and Social Science Research, 3(5), 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, F. (2007). Interpreting our heritage (4th ed.). University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tøttrup, A. P., Lillemark, M. R., Hansen, J., Svendsen, S. H., Hickinbotham, S., Toftdal, M., & Brandt, L. Ø. (2025). A concept for co-creation in participatory science: Insights from developing the archaeological next generation lab. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 10(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. (2002). The philosophic practitioner: Tourism epistemologies. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Inversini, A., Reichenberger, I., & Schlögl, S. (2017). Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change. Tourism Management, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2003). Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNESCO. (2015). Rethinking education: Towards a global common good? Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232555 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNESCO. (2021). Teaching and learning with living heritage: A resource kit for teachers. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/52066-EN.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNICEF. (2008). Child-friendly schools manual. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/Child-Friendly-Schools-Manual.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNWTO. (2022). Tourism education guidelines. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). [Google Scholar]

- Valduga, T., & Balão, A. (2023). A transdisciplinaridade e a cocriação aplicada ao processo de aprendizagem social. Aprender, (45), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dis, E. A. M., Bollen, J., Zuidema, W., van Rooij, R., & Bockting, C. L. H. (2023). ChatGPT: Five priorities for research. Nature, 614(7947), 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y., Ma, C., & Leung, M. (2024). Digital transformation in tourism higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 35, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, A. M., Green, D. P., & Cooper, J. (2020). A placebo design to detect spillovers. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A, 183(3), 1075–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. (2021). Roles of education in intangible cultural heritage tourism and managerial strategies analysis based on model of contact opportunity. In Proceedings of the 6th international conference on economics, management, law and education (Advances in economics, business and management research, Vol. 165). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | % of Respondents (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Programme of study | Tourism (Undergraduate) | 58% (38) |

| Education (Master’s) | 42% (27) | |

| Gender | Female | 68% (44) |

| Male | 32% (21) | |

| Age group | 18–22 | 47% (31) |

| 23–27 | 35% (23) | |

| 28+ | 18% (11) | |

| Visits to museums/exhibitions (≥once/year) | Yes | 54% (35) |

| Attendance at cultural events | Yes | 46% (30) |

| Reading historical/cultural books monthly | Yes | 31% (20) |

| Watching history-themed films/documentaries | Yes | 63% (41) |

| Self-graded interest in history | High/Very high | 61% (40) |

| Idea | Description | Pedagogical/Heritage Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gamification of Heritage Learning | Development of digital quizzes, interactive challenges and location-based games linked to local cultural sites and museum collections. | Encourages engagement and motivation through play-based learning; facilitates informal learning paths; increases visitation and active exploration of heritage sites. |

| Storytelling Platforms | Online platforms and mobile apps where students and community members record, share and map personal memories and local narratives connected to historical themes. | Fosters identity building and links personal memory to collective history; promotes oral history practices and intergenerational exchange; supports public history and community participation |

| Augmented Reality Applications | Use of AR to overlay historical reconstructions, interpretive layers and multimedia content on-site or in virtual museum tours. | Provides immersive, multisensory experiences that deepen appreciation of material culture; supports experiential learning and contextualized interpretation. |

| AI-Supported Personalization Tools | Adaptive quizzes, intelligent recommendation systems and text-analysis tools that personalize learning pathways and suggest heritage activities based on user profiles. | Promotes personalized learning; makes heritage relevant to individual interests; helps educators identify knowledge gaps and tailor interventions; supports scalable outreach. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marques, G.M.; Martins, R.O. No Room for Clio? Digital Approaches to Historical Awareness and Cultural Heritage Education. Tour. Hosp. 2026, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7010011

Marques GM, Martins RO. No Room for Clio? Digital Approaches to Historical Awareness and Cultural Heritage Education. Tourism and Hospitality. 2026; 7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Gonçalo Maia, and Raquel Oliveira Martins. 2026. "No Room for Clio? Digital Approaches to Historical Awareness and Cultural Heritage Education" Tourism and Hospitality 7, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7010011

APA StyleMarques, G. M., & Martins, R. O. (2026). No Room for Clio? Digital Approaches to Historical Awareness and Cultural Heritage Education. Tourism and Hospitality, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7010011