Abstract

Mental health problems are widespread in prison populations and can negatively affect inmates’ well-being. Although physical activity (PA) is known to benefit mental health in the general population, less is known about this relationship in correctional settings. This study examined the association between PA levels, symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as coping strategies among 130 male prisoners at Prison No. 1 in Wroclaw, Poland. Data were collected using validated self-report tools: the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Mini-COPE inventory. Inmates who met the criteria for Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA) reported fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression than less active participants. Individuals showing signs of mental health difficulties were also more likely to rely on avoidant coping strategies, though no clear link was found between coping style and activity level. Cluster analysis further supported the observed association between low PA and higher psychological distress. These findings suggest a potential role for PA in supporting mental health in prison settings. They also highlight the importance of identifying individuals who may be at risk due to maladaptive coping strategies. Given its exploratory nature, the study’s findings should be interpreted with caution and verified in future research with larger and more diverse samples.

1. Introduction

Mental health disorders constitute one of the most pressing public health challenges of the 21st century, affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Depression, recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the leading cause of disability globally, affects approximately 280 million individuals, whilst anxiety disorders impact the lives of over 300 million people [1]. Prevalence of these disorders in Poland reflects global trends—the prevalence of depressive episodes ranges from 4 to 6% of the adult population. Anxiety and depression create a major health risk, reaching beyond psychiatric symptoms, increasing chances of developing coronary heart disease and affecting social life, causing absenteeism from work, and social withdrawal [2].

The positive impact of regular physical activity (PA) on mental health has been proven by many studies. Liguori and Calella (2024) [3], in their scoping review, emphasize that physical exercise can serve as an effective intervention in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety while simultaneously improving overall psychological well-being. The mechanisms underlying these benefits include both neurobiological changes, such as the release of endorphins and neurotransmitters responsible for mood improvement, and psychological factors, including increased self-efficacy and enhanced self-esteem. The psychological aspect of PA includes social interactions and acquiring new abilities, both of which have a positive effect on patients suffering from high levels of anxiety, as they strengthen self-esteem and increase confidence [3].

Mental health conditions are also one of the greatest issues of current penitentiary systems. The prevalence of anxiety and depression is much higher in the offender population in comparison to the general population [4]. A systematic review on the prevalence of mental health issues in prisons in 12 Western countries estimated depression rates to be 10% for men and 12% for women [5]. In the US, two in five prisoners have a history of mental illness, which is almost twice that of the general population. The presence of depression and anxiety also creates a high risk of self-harm and suicide [4]. A survey in a UK prison found that 20% of sentenced men had suicidal thoughts and 7% had a suicide attempt [4]. The prison environment is often associated with social isolation, overcrowding, and autonomy restriction, which may not only intensify already existing mental health issues but also create a risk of the development of further conditions due to chronic stress and often limited access to proper healthcare. In prisoners, long sentence length, high criminal risk, lack of social support, and substance misuse are risk factors for suicide [2]. Due to those various social factors and high levels of environmental stress, the types of interventions that are effective in a community setting may not be appropriate for offenders [2]. That leads towards looking for alternative solutions that are not only effective but also widely available.

Although recent studies on the general population have shown a correlation between PA and mental well-being, as well as reducing the risk of depression and lowering levels of anxiety, there are not many focusing on the prisoner population.

Appropriate exercise interventions have been reported to be as effective as traditional forms of treatment. It has been shown that offenders who reported even intermediate PA during the week had scored lower levels on anxiety scales [6]. Exercise routines centered around endurance, strength, and flexibility training, including cardiovascular plus resistance training and high-intensity strength training are an important component in reducing the psychological distress of prisoners, as well as lowering depression and anxiety scale scores [6]. Clouse et al. (2012) [7] highlight the need for further research on the effectiveness of wellness programs in prison environments, while simultaneously emphasizing the importance of adapting interventions to the specific needs of this population [7].

The buffering effect of regular PA on stress, loneliness, and frustration, along with its ability to break the monotony of the sentence, makes it a potentially important tool in the management of mental health issues in prisons. The relationship between exercise and reduced feelings of hopelessness in prison populations has been demonstrated, showing the psychological benefits of PA in correctional settings [8]. Additionally, comprehensive programs combining mindfulness and PA have shown promising results in reducing anxiety, depression and stress levels in people with mental health problems in prison environments [9]. Identifying the most effective interventions for high anxiety levels and depression for prisoners could help reduce general health consequences of these conditions, as well as improve the quality of sentence and help with further resocialization. In Poland, the prison system is divided into several types, depending on the level of security and the category of inmates. These include facilities for men serving their first sentence, either in closed or semi-open conditions, as well as institutions for juveniles and repeat offenders [10]. The present study was conducted in Prison No. 1 in Wroclaw, which functions both as a closed and a semi-open prison for first-time male prisoners. Such a setting provides a relevant context for examining prisoners’ well-being, yet there is still a lack of comprehensive research on the impact of PA on mental health in Polish prisons. This represents a significant gap in scientific knowledge and penitentiary practice, highlighting the need for adjustment of treatments to the prison environment. This study aims to determine whether regular PA can serve as an appropriate intervention for high anxiety levels and depression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was conducted as a survey among inmates at Prison No. 1 in Wroclaw, Poland, one of the region’s largest correctional facilities. Its primary objective was to explore the relationship between the level of PA, the presence of anxiety or depression symptoms, and coping strategies for stress. Data were collected over two years, from 2016 to 2017, using paper-based questionnaires completed by the participants. All prisoners were invited to participate in the anonymous survey, with counselors playing a key role in informing inmates about the study and encouraging voluntary participation.

A total of 167 participants took part in this study. The mean age of participants was 30.3 years. The inmates chosen to participate in the study were the ones who chose to participate in Dr. Kosendiak’s health program, available to all inmates. Only those who fully completed the questionnaires were included in the final analysis, incomplete responses were excluded. Participation required providing informed consent, and inmates were assured that their decision to participate or withdraw at any time would not affect their status within the facility.

The study followed established ethical guidelines to ensure data confidentiality and participant rights and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University (permission no. Kb-362/2016), and permission to conduct the study was granted by the Director of the Prison.

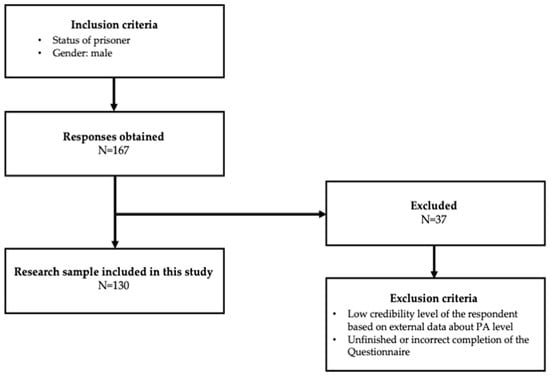

A detailed description of the study with inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

2.2. IPAQ Scale

Levels of PA were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), a validated self-reported tool designed to quantify the frequency and duration of various types of PA. The IPAQ includes questions on walking, moderate-intensity activities, vigorous-intensity activities, and sitting time, with all activities assessed over the previous seven days. To minimize the risk of overreporting, participants received clear and precise instructions on how to complete the questionnaire accurately [11].

PA data were processed by calculating the total metabolic equivalent of task (MET) minutes per week (MET-m/w) for each type of activity. The corresponding MET values applied were 3.3 for walking, 4.0 for moderate-intensity activity, and 8.0 for vigorous-intensity activity [12]. The reliability and validity of the IPAQ have been extensively verified, including in studies conducted on Polish populations [13,14,15].

2.3. HADS

Levels of depression and anxiety that a participant is experiencing were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [16]. The scale consists of 14 items, with 7 items relating to anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 relating to depression (HADS-D) [17]. Each item on the questionnaire is scored from 0 to 3.

Based on their score in separate categories, respondents were classified as follows: a score of 0–7 indicates a normal state and denotes no anxiety or depression; 8–10 means borderline abnormal case; and a score of 11 or more suggests abnormal case in terms of depression and anxiety separately [18]. The HADS’s scale reliability and validity have been verified [19].

2.4. Mini-COPE Scale

Coping strategies used by participants were assessed using the Mini-COPE inventory [20]. The tool consists of 28 items, grouped into 14 subscales that measure different strategies of coping with stress. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“I haven’t been doing this at all”) to 3 (“I’ve been doing this a lot”). These strategies can be further categorized into three main domains: problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidant coping. The results for each domain are presented as a percentage of the maximum possible score, ranging from 0 to 100%.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All collected data were compiled using Microsoft Excel (version 16.77, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed with Statistica 13 software (StatSoft, Kraków, Poland). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution and revealed that the data did not follow a normal distribution.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including frequency counts for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. For comparisons involving two independent groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. When comparing a continuous variable across three or more independent groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. The k-means clustering method was applied, utilizing Euclidean distance. Given that some variables were skewed, the stability and interpretability of the resulting clusters were carefully considered, and the optimal number of clusters was determined through v-fold cross-validation. The following variables were used in the model: Total MET m/w, HADS-D, HADS-A. All statistical tests were conducted with a significance level set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of the study participants. All participants were male. The majority came from large cities, and over two-thirds met the criteria for HEPA (Health-Enhancing Physical Activity). Anxiety disorders were more prevalent than depressive symptoms—over one-quarter of the participants had abnormal levels of anxiety, while 14.6% showed abnormal levels of depression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

Table 2 displays the main characteristics of IPAQ, HADS, and mini-COPE. For the IPAQ, nearly half of the total PA was attributed to Vigorous PA, while Moderate PA constituted the smallest share. On the HADS, scores for the anxiety subscale were higher than for depression. In the mini-COPE, the most frequently used coping strategy was problem-focused; emotion-focused and avoidant strategies were used less frequently and at similar levels.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of study variables.

3.3. Differences Between Study Variables and IPAQ Levels

Table 3 shows the differences between PA levels and the results of the mini-COPE and HADS questionnaires. A statistically significant association was observed in the HADS: minimally active individuals had the highest scores in both anxiety and depression, while those with HEPA-level activity had the lowest. No statistically significant associations were found for the mini-COPE variables.

Table 3.

Differences between study variables and IPAQ levels.

3.4. Differences Between HADS Levels for Different Subscales and Study Variable

Table 4 presents associations between HADS subscale levels, PA, and mini-COPE strategies. Participants without clinically significant depressive symptoms had higher Total and Vigorous PA, which decreased with increasing depression scores. A similar trend was observed between anxiety levels and Total PA. Other associations did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4.

Differences between HADS levels for different subscales and study variables.

3.5. Differences Between Study Variables and Mental Health State

Table 5 presents the relationship between PA and a dichotomous classification of mental health status (normal vs. abnormal). Participants classified as having abnormal mental health had significantly lower levels of Vigorous and Total PA. They also exhibited a higher tendency to use Avoidant coping strategies.

Table 5.

Differences between study variables and mental health state.

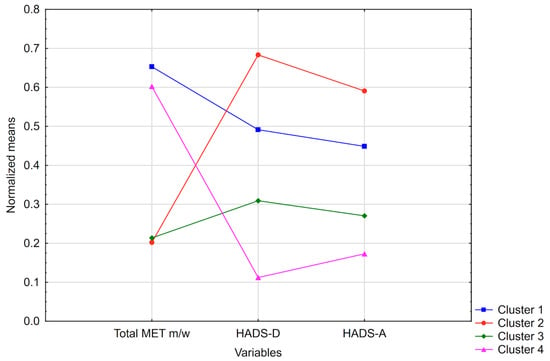

3.6. Cluster Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates cluster analysis involving Total PA and raw HADS scores for anxiety and depression. Cluster 2, characterized by the highest levels of depression and anxiety, showed the lowest PA. Cluster 3, despite similarly low PA as Cluster 2, had relatively low levels of depression and anxiety. Clusters 1 and 4 had similarly high PA but showed notable differences in psychological symptoms. Moreover, Cluster 4 was the only group where anxiety levels were higher than depression.

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis.

4. Discussion

This study explored the relationship between PA, mental health, and coping strategies among a group of male prisoners at Prison No. 1 in Wroclaw, Poland. The focus on men reflects the reality of the prison population in Poland, where women make up only a small minority. According to Eurostat, just 5.4% of prisoners across Europe are female, and in Poland, this number is even lower at only 3.68% as of 2024 [21,22]. While this narrows the scope of the study and limits gender-based comparisons, it also allows for a more targeted examination of male-specific patterns of coping and psychological health, which remain understudied, especially in Central and Eastern Europe.

One of the most notable findings was that over two-thirds of the participants met the criteria for HEPA [23]. Although this number may seem unusually high, it is not without precedent. For instance, a French study found that 41.2% of male inmates were highly active [24]. Similarly, research from Germany reported that 74% of prisoners engaged in at least five hours of sport per week [23]. These results suggest that PA may play a more significant role in prison routines than is often assumed. In Poland, this may be partly due to formal policies. According to a national regulation issued by the Director General of the Prison Service in 2016, PA is encouraged and organized through general fitness sessions, team sports, and other recreational activities during inmates’ free time [25]. Moreover, the European Prison Rules regard well-organized fitness activities and recreational opportunities as an integral part of the prison regime [26].

Mental health problems are a well-documented concern in prison systems. According to the WHO, prisoners are up to seven times more likely to experience mental health disorders than the general population [27]. As Baranyi et al. emphasize, many prisoners come from disadvantaged backgrounds, have experienced childhood trauma, or have struggled with substance use, all of which increase the risk of psychological disorders [28]. On top of that, difficult prison environments marked by poor living conditions or exposure to violence can make mental health worse [29]. In our study, more than 25% of participants showed abnormal levels of anxiety, while 14.6% had symptoms of clinical depression. Anxiety appeared to be more prevalent than depression, which is consistent with findings from other prison studies. For example, a large-scale survey in French prisons found anxiety disorders in 44.4% of new inmates, compared to 27.2% with depressive disorders [30]. These elevated rates likely reflect the day-to-day stress of prison life, including unpredictability, restricted freedom, and difficult social dynamics. These conditions can easily lead to heightened alertness and persistent worry. Research shows that such stressors, including lack of autonomy, overcrowding, isolation, and unpredictability of release, significantly contribute to mental distress among inmates [31].

Although many studies confirm the mental health benefits of PA [32], our findings extend this evidence to the prison context, demonstrating that the same association applies to inmates. In our sample, inmates with the lowest levels of PA reported the highest levels of both anxiety and depression. In contrast, those who met HEPA criteria scored lowest on these mental health indicators. These observations are consistent with international findings. For instance, Spanish inmates who maintained regular PA during their incarceration reported significantly better physical and mental health, as well as fewer anxiety or depressive symptoms compared to inactive inmates [33]. Similarly, the Hessian Prison Sport Study in Germany found that prisoners engaging in ≥5 h of PA per week, both organized and informal, reported substantially better mental health and life satisfaction than less active peers [23]. A systematic review of 14 studies further concluded that prison-based sport programs can significantly improve psychological well-being [34]. Taken together, these findings support that PA in prison settings should be treated. While the cross-sectional nature of the data means the direction of the relationship between PA and mental health cannot be firmly established, the results should still be interpreted carefully. Overall, they support the growing perspective that PA in prison settings should be considered not just as a leisure option, but as a structured therapeutic tool with substantial mental health benefits.

According to Endler and Parker’s model, people tend to use one of three broad coping styles: problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidant coping [35]. Problem-focused strategies aim to reduce or remove the source of stress by taking practical steps to solve the problem or by adapting to the situation when the stressor cannot be eliminated [36]. In our study, the problem-focused strategy was the most reported approach among participants, which is consistent with previous research conducted in penitentiary settings. For instance, another study found that incarcerated individuals most frequently relied on active forms of coping, such as planning and problem-solving [37].

In contrast, emotion-focused and especially avoidant coping strategies were reported less frequently. However, avoidant coping revealed noteworthy and statistically significant results in our analysis. Participants with symptoms of poor mental health, either anxiety or depression, were significantly more likely to rely on avoidance. This could take the form of denial, distraction, or even maladaptive behaviors such as substance use [37]. Previous studies have consistently shown that avoidant coping is associated with poorer mental health outcomes and may contribute to the onset or worsening of psychological symptoms [36]. This was also reflected in a Polish prison study, where individuals with lower perceived well-being tended to use avoidant and disengaged strategies, while those with better quality of life more often engaged in active coping [38]. These findings highlight the importance of identifying inmates who lean toward avoidant coping early on and offering interventions to promote more adaptive approaches.

It is worth noting that, despite associations between coping styles and mental health outcomes, we found no statistically significant differences in coping strategies between groups with different PA levels. This suggests that PA and coping mechanisms may operate as independent dimensions in the psychological functioning of incarcerated individuals. In line with previous research, certain coping styles, such as avoidance or emotion-focused strategies, are associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety, whereas problem-focused coping tends to relate to lower symptom levels [38,39]. Currently, there is a lack of research examining the link between PA and coping styles in prison settings, which highlights the need for further investigation into how behavioral and psychological resources interact under conditions of incarceration.

To further explore these dynamics, we conducted a cluster analysis that revealed four distinct subgroups within the sample, each characterized by unique combinations of psychological symptoms and PA levels.

Cluster 2 included individuals with both the highest levels of depression and anxiety, and simultaneously the lowest levels of PA. This pattern is consistent with the well-documented protective effect of PA against psychological distress, particularly among incarcerated individuals [6]. This group may reflect a cycle in which low activity contributes to mental health problems, which in turn reduce motivation to engage in PA. Biological mechanisms, such as reduced production of endorphins or dysregulation of the stress hormone cortisol, may help explain this association [40].

Interestingly, Cluster 3 presented a more unexpected pattern: participants reported low levels of PA but also relatively low levels of anxiety and depression. This suggests that the relationship between PA and mental health may not be strictly linear. It is possible that individuals in this group had access to other psychological resources, such as strong coping skills, emotional resilience, or social support, which helped buffer the negative effects of inactivity. However, more targeted research is needed to clarify this profile.

Cluster 4 featured participants with high levels of PA, but relatively elevated anxiety symptoms. This pattern may reflect a compensatory use of PA as an emotion-regulation strategy, where individuals engage in PA to manage anxiety without fully resolving underlying psychological issues. In contrast, Cluster 1 included individuals with both high PA and low psychological symptoms, representing the most favorable profile. This comparison suggests that while PA can support emotional regulation, its impact varies across individuals, and high activity levels alone may not be sufficient to prevent elevated anxiety.

Taken together, these findings support the idea that the relationship between PA and mental health is complex and likely moderated by individual, contextual, and psychological factors. They underscore the need for personalized approaches when designing interventions in prison settings and suggest that PA, while broadly beneficial, may serve different psychological functions depending on the individual’s emotional state and coping capacities.

The findings of this study underline the importance of integrating structured PA as a central component of prison health programs. Given the association between high levels of PA and improved mental health outcomes, prison authorities should consider expanding access to organized fitness sessions, sport-based programs, and recreational opportunities. Additionally, screening inmates for coping styles, particularly the use of avoidant strategies, could help identify individuals at higher risk of mental health problems and allow for early, targeted psychosocial support. It is equally important that prison staff and authorities are adequately informed about the potential psychological difficulties faced by inmates and are provided with appropriate training on how to recognize early warning signs and implement effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Despite the valuable insights offered by this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample consisted exclusively of male prisoners, which limits the ability to generalize findings across genders. Differences in how men and women respond to stress, engage in PA, and use coping strategies should be explored in future studies. The mean age of participants was 30.3 years, which is slightly lower than the average age reported for the general male prison population in Poland, which may limit the generalizability of our findings [41]. Additionally, all data were self-reported, which raises the possibility of bias, particularly in a prison setting where responses may overreport positive behaviors or underreport negative experiences due to social desirability or misunderstanding of the questions. This is especially relevant for PA, as the IPAQ is known to systematically overestimate activity levels, particularly vigorous PA. Notably, the high proportion of inmates meeting HEPA criteria in our sample is substantially above rates reported in comparable prison and community samples and should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, given the exploratory nature of the study and the large number of statistical tests conducted, there is an increased risk of Type I error. Although targeted post hoc tests following significant Kruskal–Wallis results were performed to reduce the number of comparisons, marginally significant findings should still be interpreted with caution, and replication in larger samples is needed to confirm these associations. PA and mental health symptoms were measured over a single 7-day period, providing only a snapshot of participants’ typical behavior and psychological state, which may fluctuate over time. Additionally, the study had a relatively small sample size. In future studies, we will consider improved distribution and monitoring of questionnaire completion, which will allow for a larger sample size. The study also lacked data on other relevant factors, such as sentence length, time served, prior psychiatric diagnoses, and access to social support, all of which could influence mental health outcomes. Future studies should aim to address these gaps using longitudinal designs and objective measurement tools to strengthen validity and expand generalizability. Additionally, Mini-COPE subscales were aggregated into three broader domains to simplify interpretation and accommodate the limited sample size. While this approach allowed examination of general coping patterns in relation to PA and mental health, it may have obscured more specific relationships that could be detected at the subscale level. Cluster analysis was performed using v-fold cross-validation; however, no formal indices of cluster validity were reported, and the data were skewed, which could have influenced the stability and interpretability of the identified clusters. Finally, standardized effect sizes were not reported. Future studies could include them to provide additional insight into the magnitude and practical significance of the observed associations. This work is exploratory in nature; thus the interpretations are limited.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine whether PA can be an effective intervention for improving mental health in prison settings. The results showed that inmates with the lowest levels of PA reported the highest levels of anxiety and depression, while those who met the HEPA guidelines demonstrated the most favorable mental health outcomes. This association was both statistically significant and clinically relevant. Furthermore, participants with symptoms of poor mental health were more likely to rely on avoidant coping strategies, highlighting the importance of early detection and targeted psychological support for this group.

The findings suggest an association between PA and mental health among prisoners, highlighting the potential relevance of PA in correctional facilities. These results indicate that further research, particularly longitudinal or interventional studies, could explore whether structures and individualized PA interventions might benefit psychological well-being in this population. The study also underscores the importance of considering inmates’ specific psychological needs and coping styles when designing such programs.

By focusing on the Polish penitentiary system, this research addresses a notable gap in current knowledge and offers a valuable foundation for future studies aimed at developing evidence-based rehabilitation programs in the prison environment.

Ultimately, these findings show the potential for future findings that could significantly improve the quality of life of incarcerated individuals and may potentially support their successful reintegration into society. Future research should continue exploring the broader context and contributing factors influencing the effectiveness of such interventions within the Polish correctional system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.K. and B.B.C.; methodology, A.A.K.; validation, A.A.K. and B.B.C.; formal analysis, B.B.C. and D.K.; investigation, A.A.K. and B.B.C.; resources, A.A.K. and B.B.C.; data curation, B.B.C. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.K., B.B.C., D.K., A.W.T. and W.H.; writing—review and editing, B.B.C. and W.H.; visualization, B.B.C. and W.H.; supervision, A.A.K., B.B.C. and W.H.; project administration, B.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of WROCLAW MEDICAL UNIVERSITY (permission No. KB-362/2016, approval date: 15 March 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to the inclusion of information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants in accordance with the decision of the Ethics Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PA | Physical activity |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent of Task |

| MET-m/w | Metabolic Equivalent of Task minutes per week |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HADS-A | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (the Anxiety subscale) |

| HADS-D | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (the Depression subscale) |

| IQR | Interquartile Ranges |

| HEPA | Health-Enhancing Physical Activity |

| MH | Mental Health |

References

- GBD Results. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Perry, A. A Systematic Review of Interventions for Anxiety, Depression, and PTSD in Adult Offenders. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2015, 59, 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, F.; Calella, P. Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Prisoners: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Prison. Health 2024. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, N.; Meltzer, H.; Gatward, R.; Coid, J.; Deasy, D. Psychiatric Morbidity Among Prisoners: Summary Report; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S.; Danesh, J. Serious Mental Disorder in 23000 Prisoners: A Systematic Review of 62 Surveys. Lancet 2002, 359, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, C.; di Cagno, A.; Fiorilli, G.; Giombini, A.; Borrione, P.; Baralla, F.; Marchetti, M.; Pigozzi, F. Participation in a 9-Month Selected Physical Exercise Programme Enhances Psychological Well-Being in a Prison Population. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2015, 25, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, M.L.; Mannino, D.; Curd, P.R. Investigation of the Correlates and Effectiveness of a Prison-Based Wellness Program. J. Correct. Health Care 2012, 18, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cashin, A.; Potter, E.; Butler, T. The Relationship between Exercise and Hopelessness in Prison. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 15, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.; Cangas, A.J.; Mañas, I.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Langer, Á.I.; Navarro, N.; Lirola, M.-J. Effects of a Mindfulness and Physical Activity Programme on Anxiety, Depression and Stress Levels in People with Mental Health Problems in a Prison: A Controlled Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustawa z Dnia 6 Czerwca 1997 r.—Kodeks Karny Wykonawczy. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19970900557 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Biernat, E.; Stupnicki, R.; Gajewski, A. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Polish Version. Phys. Educ. Sport 2007, 51, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hagströmer, M.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): A Study of Concurrent and Construct Validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, B.B.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S.; Wasilewski, A.; Kosendiak, A.A. Physical Activity, Alcohol, and Cigarette Use in Urological Cancer Patients over Time since Diagnosis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergier, J.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L.; Biliński, P.; Paprzycki, P.; Wojtyła, A. Physical Activity of Polish Adolescents and Young Adults According to IPAQ: A Population Based Study. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 19, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.; Marshall, A.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.; Booth, M.; Ainsworth, B.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.A.; Muzzatti, B.; Altoè, G. Defining Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Structure by Confirmatory Factor Analysis: A Contribution to Validation for Oncological Settings. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2330–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemła, A.; Nowicka-Sauer, K.; Jarmoszewicz, K.; Wera, K.; Batkiewicz, S.; Pietrzykowska, M. Measures of Preoperative Anxiety. Anestezjol. Intensywna Ter. 2019, 51, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An Updated Literature Review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu i Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; ISBN 978-83-60733-47-9. [Google Scholar]

- Prison Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Prison_statistics (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Poland: Persons in Prisons and Remand Centers by Sex. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1337257/poland-persons-in-prisons-and-remand-centers-by-sex/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Hilpisch, C.; Müller, J.; Mutz, M. Physical, Mental, and Social Health of Incarcerated Men: The Relevance of Organized and Informal Sports Activities. J. Correct. Health Care 2023, 29, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagarrigue, A.; Ajana, S.; Capuron, L.; Féart, C.; Moisan, M.-P. Obesity in French Inmates: Gender Differences and Relationship with Mood, Eating Behavior and Physical Activity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowalska-Kapuścik, D.; Libor, G. Sport i Czas Wolny w Perspektywie Interdyscyplinarnej; e-bookowo: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-7859-988-3. [Google Scholar]

- de l’Europe, C. (Ed.) Règles Pénitentiaires Européennes; Editions du Conseil de l’Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2006; ISBN 978-92-871-5981-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Figueroa, H.; Camino-Proaño, A. Mental and Behavioral Disorders in the Prison Context. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2022, 24, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, G.; Scholl, C.; Fazel, S.; Patel, V.; Priebe, S.; Mundt, A.P. Severe Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders in Prisoners in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Studies. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e461–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertie, A.; Bourey, C.; Stephenson, R.; Bautista-Arredondo, S. Connectivity, Prison Environment and Mental Health among First-Time Male Inmates in Mexico City. Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fovet, T.; Plancke, L.; Amariei, A.; Benradia, I.; Carton, F.; Sy, A.; Kyheng, M.; Tasniere, G.; Amad, A.; Danel, T.; et al. Mental Disorders on Admission to Jail: A Study of Prevalence and a Comparison with a Community Sample in the North of France. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, W.; Irfan, S.; Nawab, S. Amtullah Quality of Life as a Predictor of Psychological Distress and Self Esteem among Prisoners. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, G.E.; Colquhoun, L.; Lancastle, D.; Lewis, N.; Tyson, P.J. Review: Physical Activity Interventions for the Mental Health and Well-Being of Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 26, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penado Abilleira, M.; Ríos-de-Deus, M.-P.; Tomé-Lourido, D.; Rodicio-García, M.-L.; Mosquera-González, M.-J.; López-López, D.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Relationship between Sports Practice, Physical and Mental Health and Anxiety–Depressive Symptomatology in the Spanish Prison Population. Healthcare 2023, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.; Breslin, G.; Hassan, D. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sport-Based Interventions on the Psychological Well-Being of People in Prison. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 12, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional Assessment of Coping: A Critical Evaluation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszko, M.; Iwański, R.; Jarzębińska, A. The Relationship Between Personality Traits and Coping Styles Among First-Time and Recurrent Prisoners in Poland. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziej, K.; Kurowska, A.; Majda, A. Intensification of Type D Personality Traits and Coping Strategies of People Staying in Polish Penitentiary Institutions-Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowroński, B.; Talik, E. Coping with stress and the sense of quality of life in inmates of correctional facilities. Psychiatr. Pol. 2018, 52, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarchuk, O.; Balakhtar, V.; Pinchuk, N.; Pustovalov, I.; Pavlenok, K. Coping with Stressfull Situations Using Coping Strategies and Their Impact on Mental Health. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, 2024spe034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, N.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Mastorakos, G. Endocrine Responses of the Stress System to Different Types of Exercise. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statystyka Roczna—Służba Więzienna. Available online: http://www.sw.gov.pl/strona/statystyka-roczna (accessed on 6 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).