Smartphone Addiction Among Greek University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the SAS-SV Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

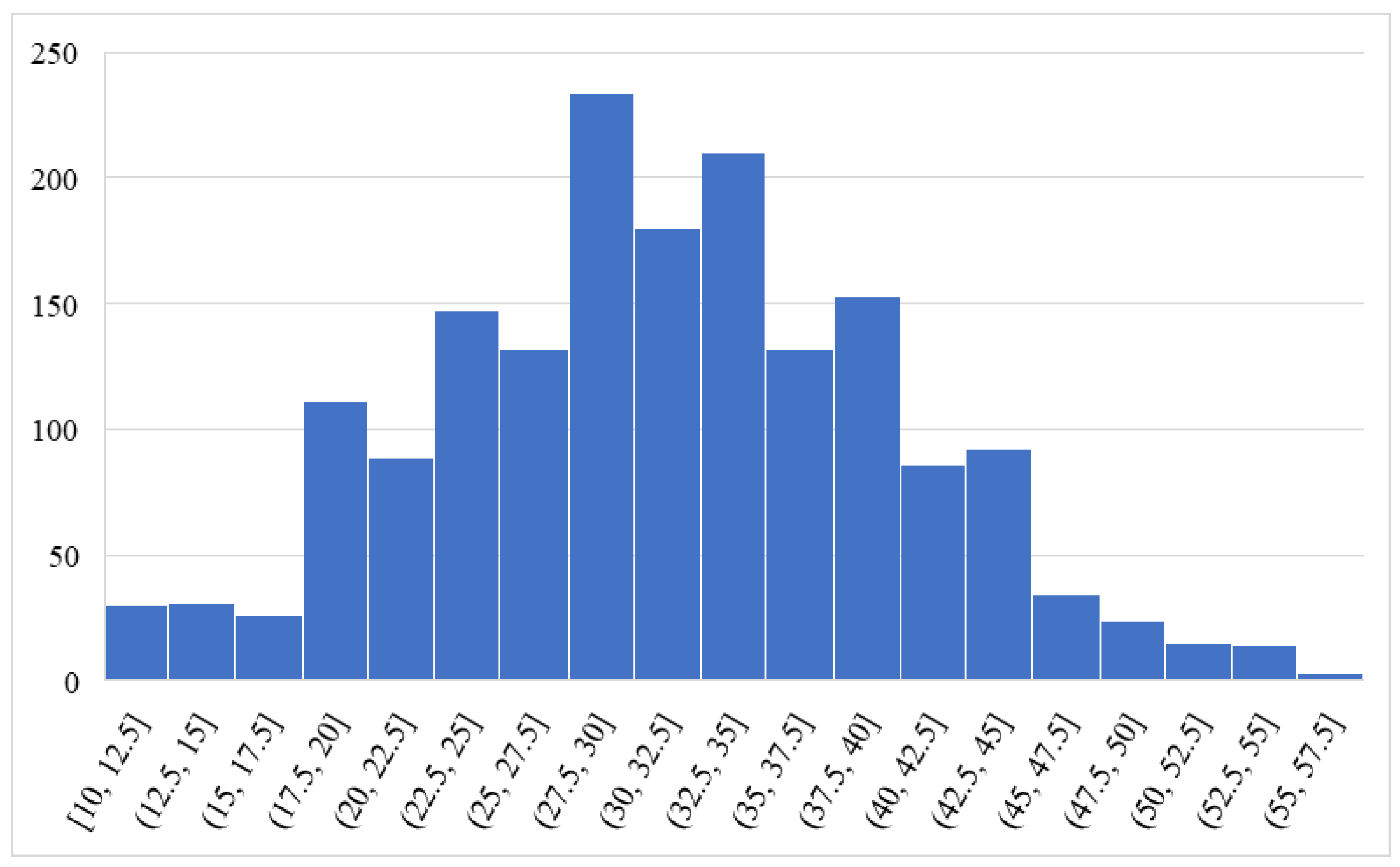

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sunday, O.J.; Adesope, O.O.; Maarhuis, P.L. The Effects of Smartphone Addiction on Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, J.; Marmet, S.; Wicki, M.; Khazaal, Y.; Gmel, G. Associations between Smartphone Use and Mental Health and Well-Being among Young Swiss Men. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, M.S.; Fox, M.; Coman, R.; Ratan, Z.A.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Perspectives and Experiences of Smartphone Overuse among University Students in Umm Al-Qura University (UQU), Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Garg, S.; Arora, K. Pattern of Mobile Phone Usage and Its Effects on Psychological Health, Sleep, and Academic Performance in Students of a Medical University. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J. Problematic Smartphone Usage and Subjective and Psychological Well-Being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.A.; McCarthy, S. Antecedents and Consequences of Problematic Smartphone Use: A Systematic Literature Review of an Emerging Research Area. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salepaki, A.; Zerva, A.; Kourkouridis, D.; Angelou, I. Unplugging Youth: Mobile Phone Addiction, Social Impact, and the Call for Digital Detox. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panova, T.; Carbonell, X. Is Smartphone Addiction Really an Addiction? J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Wegmann, E.; Sariyska, R.; Demetrovics, Z.; Brand, M. How to Overcome Taxonomical Problems in the Study of Internet Use Disorders and What to Do with “Smartphone Addiction”? J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.; Griffiths, M. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. The Relationship between Anxiety Symptom Severity and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Review of the Literature and Conceptual Frameworks. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 62, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J. Personality and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Facet-Level Analysis Using the Five Factor Model and HEXACO Frameworks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Li, J.; Barkley, J.E. College Students’ Cell Phone Use and Attachment to Parents and Peers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, T.; Xie, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Network Analysis of the Association between Social Anxiety and Problematic Smartphone Use in College Students. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1508756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soraci, P.; Demetrovics, Z.; Bevan, N.; Pisanti, R.; Servidio, R.; Di Bernardo, C.; Griffiths, M.D. FoMO and Psychological Distress Mediate the Relationship between Life Satisfaction, Problematic Smartphone Use, and Problematic Social Media Use. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E.; Svoli, H. The Association between Internet User Characteristics and Dimensions of Internet Addiction among Greek Adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2013, 11, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hesselle, L.C.; Montag, C. Effects of a 14-Day Social Media Abstinence on Mental Health and Well-Being: Results from an Experimental Study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadiotis, A.; Bacopoulou, F.; Kokka, I.; Vlachakis, D.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C.; Roussos, P. Validation of the Greek Version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale in Undergraduate Students. EMBnet J. 2021, 26, e975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Won, W.-Y.; Park, J.-W.; Min, J.-A.; Hahn, C.; Gu, X.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, D.-J. Development and Validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Makai, A.; Gyuró, M.; Komáromy, M.; Császár, G. The Validity and Reliability of the Hungarian Version of Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version (SAS-SV-HU) among University Students. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fuentes, S.; Martínez-Álvarez, I.; Llamas-Salguero, F.; Pineda-Zelaya, I.S.; Merino-Soto, C.; Chans, G.M. Psychometric Properties of the Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short Version (SAS-SV) in Honduran University Students. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateno, M.; Kim, D.J.; Teo, A.R.; Skokauskas, N.; Guerrero, A.P.S.; Kato, T.A. Smartphone Addiction in Japanese College Students: Usefulness of the Japanese Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale as a Screening Tool for a New Form of Internet Addiction. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, A.; Bukurov, B.; Kocic, I.; Soldatovic, I.; Mihajlovic, S.; Nesic, D.; Vukovic, M.; Ladjevic, N.; Grujicic, S.S. The Validity and Reliability of the Serbian Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale—Short Version. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escalera-Chávez, M.E.; Rojas-Kramer, C.A. SAS-SV Smartphone Addiction Scale in Mexican University Students. Educ. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8832858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Lust, K.; Chamberlain, S.R. Problematic Smartphone Use Associated with Greater Alcohol Consumption, Mental Health Issues, Poorer Academic Performance, and Impulsivity. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumosleh, J.-M.; Jaalouk, D. Depression, Anxiety, and Smartphone Addiction in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, N.O.; Almasaad, J.M.; Busaeed, R.B.; Aljafari, D.A.; Khan, M.A. Smartphone Addiction, Stress, and Depression among University Students. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R. Self-Control and Problematic Smartphone Use among Italian University Students: The Mediating Role of the Fear of Missing Out and of Smartphone Use Patterns. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4101–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A “Components” Model of Addiction within a Biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, M.M.; Krishnan, B.; Mokal, S.J.; Latti, R.G. An Analysis of Smartphone Addiction among MBBS Students. Indian J. Clin. Anat. Physiol. 2020, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescollotto, F.F.; Castro, E.M.; Pelai, E.B.; Pertille, A.; Bigaton, D.R. Translation of the Short Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale into Brazilian Portuguese: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Testing of Measurement Properties. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, X. The Prevalence and Psychosocial Factors of Problematic Smartphone Use among Chinese College Students: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 877277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okasha, T.; Saad, A.; Ibrahim, I.; Elhabiby, M.; Khalil, S.; Morsy, M. Prevalence of Smartphone Addiction and Its Correlates in a Sample of Egyptian University Students. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Borda-Mas, M. Problematic Smartphone Use and Specific Problematic Internet Uses among University Students and Associated Predictive Factors: A Systematic Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 28, 7111–7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.A.; Sandra, D.A.; Veissière, S.P.; Langer, E.J. Sex, Age, and Smartphone Addiction across 41 Countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 23, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.Y.C.; Ismail, M.A.A.; Mohammad, J.A.M.; Yusoff, M.S.B. The Relationship of Smartphone Addiction with Psychological Distress and Neuroticism among University Medical Students. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.M.; Balica, R.Ș.; Lazăr, E.; Bușu, V.O.; Vașcu, J.E. Smartphone Addiction Risk, Technology-Related Behaviors and Attitudes, and Psychological Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 997253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numanoğlu-Akbaş, A.; Suner-Keklik, S.; Yakut, H. Investigation of the Relationship between Smartphone Addiction and Physical Activity in University Students. Baltic J. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon Júnior, L.J.F.; Ribeiro, C.H.T.; de Sousa Fortes, L.; Barbosa, B.T.; da Silva Neto, L.V. Smartphone Addiction Is Associated with Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, Stress, Tension, Confusion, and Insomnia: A Cross-Sectional and Comparative Study with Physically and Non-Physically Active Adults in Self-Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Salud Ment. 2021, 44, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, A.; Alboali, R.; Alharbi, W.; Saleh, O. Smartphone Addiction and Its Complications Related to Health and Daily Activities among University Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multicenter Study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 3220–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, K.; Akgönül, M.; Akpinar, A. Relationship of Smartphone Use Severity with Sleep Quality, Depression, and Anxiety in University Students. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M.; Hawi, N.S. Relationships among Smartphone Addiction, Stress, Academic Performance, and Satisfaction with Life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, S.; Shahnawaz, M.G.; Griffiths, M.D. Smartphone Addiction in Students: A Qualitative Examination of the Components Model of Addiction Using Face-to-Face Interviews. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chang, L.-R.; Lee, Y.-H.; Tseng, H.-W.; Kuo, T.B.J.; Chen, S.-H. Development and Validation of the Smartphone Addiction Inventory (SPAI). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Cagigal, A.; Kealy, C.; Potts, C.; Mulvenna, M.D.; Byrne, M.; Barry, M.M.; Donohoe, G. Digital Mental Health Interventions for University Students with Mental Health Difficulties: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2025, 19, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Fialho, P.M.; Wenig, V.; Heumann, E.; Müller, M.; Stock, C.; Pischke, C.R. Digital Public Health Interventions for the Promotion of Mental Well-Being and Health Behaviors among University Students: A Rapid Review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Weakly Agree (%) | Weakly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly Disagree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Missing planned work due to smartphone use | 2.01 | 7 | 14 | 15.95 | 27.71 | 33.33 |

| 2 | Having a hard time concentrating in class, while doing assignments, or while working due to smartphone use | 4.93 | 17.33 | 24.67 | 16.98 | 22.89 | 13.2 |

| 3 | Feeling pain in the wrists or at the back of the neck while using a smartphone | 1.78 | 8.2 | 11.65 | 13.77 | 26.8 | 37.81 |

| 4 | Won’t be able to stand not having a smartphone | 18.07 | 28.17 | 20.02 | 13.88 | 13.14 | 6.71 |

| 5 | Feeling impatient and fretful when I am not holding my smartphone | 2.58 | 10.5 | 17.56 | 21.86 | 29.66 | 17.84 |

| 6 | Having my smartphone in my mind even when I am not using it | 3.16 | 9.58 | 16.47 | 20.37 | 31.33 | 19.1 |

| 7 | I will never give up using my smartphone even when my daily life is already greatly affected by it. | 5.85 | 14.29 | 19.56 | 21.29 | 23.52 | 15.49 |

| 8 | Constantly checking my smartphone so as not to miss conversations between other people on Twitter or Facebook | 10.73 | 22.38 | 24.1 | 16.29 | 17.1 | 9.41 |

| 9 | Using my smartphone longer than I had intended | 16.35 | 32.76 | 22.32 | 14.69 | 9.47 | 4.42 |

| 10 | The people around me tell me that I use my smartphone too much. | 6.71 | 14.11 | 16.81 | 16.52 | 26.45 | 19.39 |

| Variable | Spearsman’s Rho | p-Value | Benjamini–Hochberg Threshold | Sig. After BH Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen time | 0.147 | <0.001 | 0.009 | correlated |

| Sex | −0.120 | <0.001 | 0.014 | correlated |

| Age | −0.060 | 0.012 | 0.027 | correlated |

| Household members | 0.039 | 0.104 | 0.050 | uncorrelated |

| Average Grade | −0.043 | 0.089 | 0.045 | uncorrelated |

| Smoking | 0.045 | 0.060 | 0.041 | uncorrelated |

| Alcohol | 0.163 | <0.001 | 0.005 | correlated |

| Exercise | −0.097 | <0.001 | 0.023 | correlated |

| BMI | −0.050 | 0.038 | 0.036 | uncorrelated |

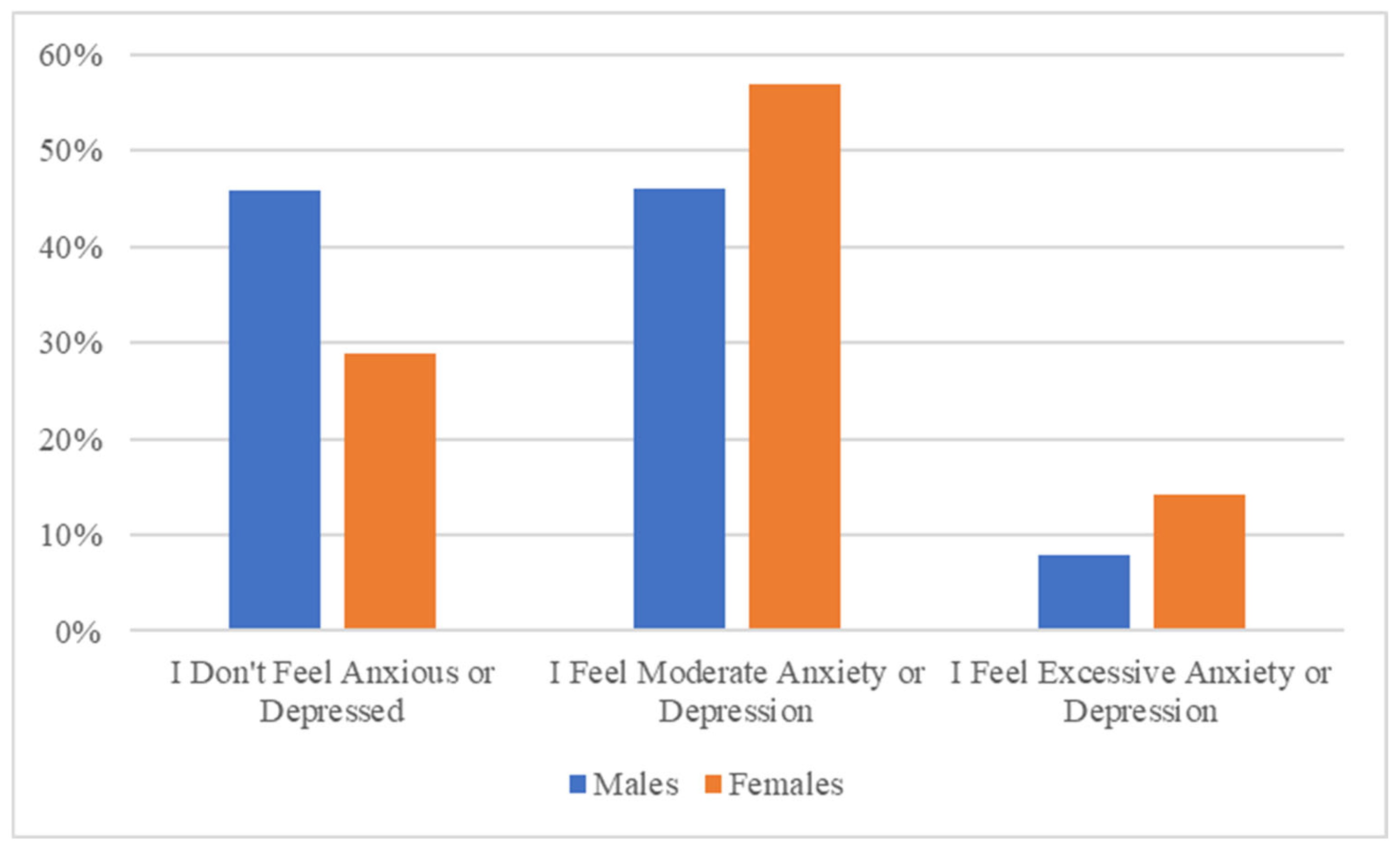

| Anxiety/Depression | 0.099 | <0.001 | 0.018 | correlated |

| Self-rated health | −0.055 | 0.023 | 0.032 | correlated |

| Variable | β | Std Err | t Stat | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 35.457 | 3.31 | 10.70 | 0.000 | |

| Screen time | 0.096 | 0.01 | 7.39 | 0.000 | 1.02 |

| Sex | −1.998 | 0.48 | −4.15 | 0.000 | 1.29 |

| Age | −0.355 | 0.08 | −4.41 | 0.000 | 1.06 |

| Average grade | −0.306 | 0.25 | −1.21 | 0.226 | 1.06 |

| Household members | 0.388 | 0.18 | 2.13 | 0.033 | 1.01 |

| BMI | 0.003 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.972 | 1.14 |

| Smoking | 0.097 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.722 | 1.26 |

| Alcohol | 1.399 | 0.21 | 6.63 | 0.000 | 1.17 |

| Exercise | −0.423 | 0.23 | −1.81 | 0.070 | 1.12 |

| Anxiety/depression | 0.823 | 0.35 | 2.35 | 0.019 | 1.13 |

| Self-rated health | −0.001 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.964 | 1.13 |

| Mann–Whitney U Tests | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean Rank (PSU) | Mean Rank (Non-PSU) | U | Raw p-Value | BH Threshold | Effect (r) | Sig. (BH) |

| Screen Time | 896.7 | 790.4 | 305,559.5 | <0.0001 | 0.0091 | 0.127 | Yes |

| Age | 851.6 | 891.8 | 362,150 | 0.0850 | 0.0273 | 0.046 | Νο |

| Average grade | 753.9 | 789.9 | 283,713 | 0.1124 | 0.0364 | 0.047 | Νο |

| Household members | 876.6 | 867.6 | 375,753.5 | 0.6944 | 0.0500 | 0.010 | Νο |

| Smoking | 891.4 | 853.2 | 362,995 | 0.0644 | 0.0182 | 0.044 | Νο |

| Alcohol | 966.5 | 848.5 | 354,322 | <0.0001 | 0.0045 | 0.131 | Yes |

| Exercise | 850.7 | 892.7 | 361,376.5 | 0.0691 | 0.0227 | 0.048 | Νο |

| BMI | 878.5 | 865.7 | 374,056.5 | 0.4757 | 0.0455 | 0.015 | Νο |

| Anxiety/depression | 904.1 | 840.9 | 352,123 | 0.0036 | 0.0136 | 0.073 | Yes |

| Self-rated health | 852.2 | 891.2 | 362,698.5 | 0.1041 | 0.0318 | 0.045 | Νο |

| Chi-Square Test of Independence | |||||||

| Variable | Males (PSU/Non-PSU) | Females (PSU/Non-PSU) | χ2 (df) | Raw p-value | BH Threshold | Effect (φ) | Sig. (BH) |

| Sex | 445/437 | 413/448 | 1.08 (1) | 0.299 | 0.041 | 0.025 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karali, E.; Briola, K.; Emmanouil-Kalos, A.; Sidiropoulos, S.; Ginis, A.; Vozikis, A. Smartphone Addiction Among Greek University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the SAS-SV Scale. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040152

Karali E, Briola K, Emmanouil-Kalos A, Sidiropoulos S, Ginis A, Vozikis A. Smartphone Addiction Among Greek University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the SAS-SV Scale. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(4):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040152

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarali, Evangelia, Konstantina Briola, Alkinoos Emmanouil-Kalos, Symeon Sidiropoulos, Alexandros Ginis, and Athanassios Vozikis. 2025. "Smartphone Addiction Among Greek University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the SAS-SV Scale" Psychiatry International 6, no. 4: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040152

APA StyleKarali, E., Briola, K., Emmanouil-Kalos, A., Sidiropoulos, S., Ginis, A., & Vozikis, A. (2025). Smartphone Addiction Among Greek University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the SAS-SV Scale. Psychiatry International, 6(4), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040152