The Hidden Challenge: Male Eating Disorders in the Middle East: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Cultural Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

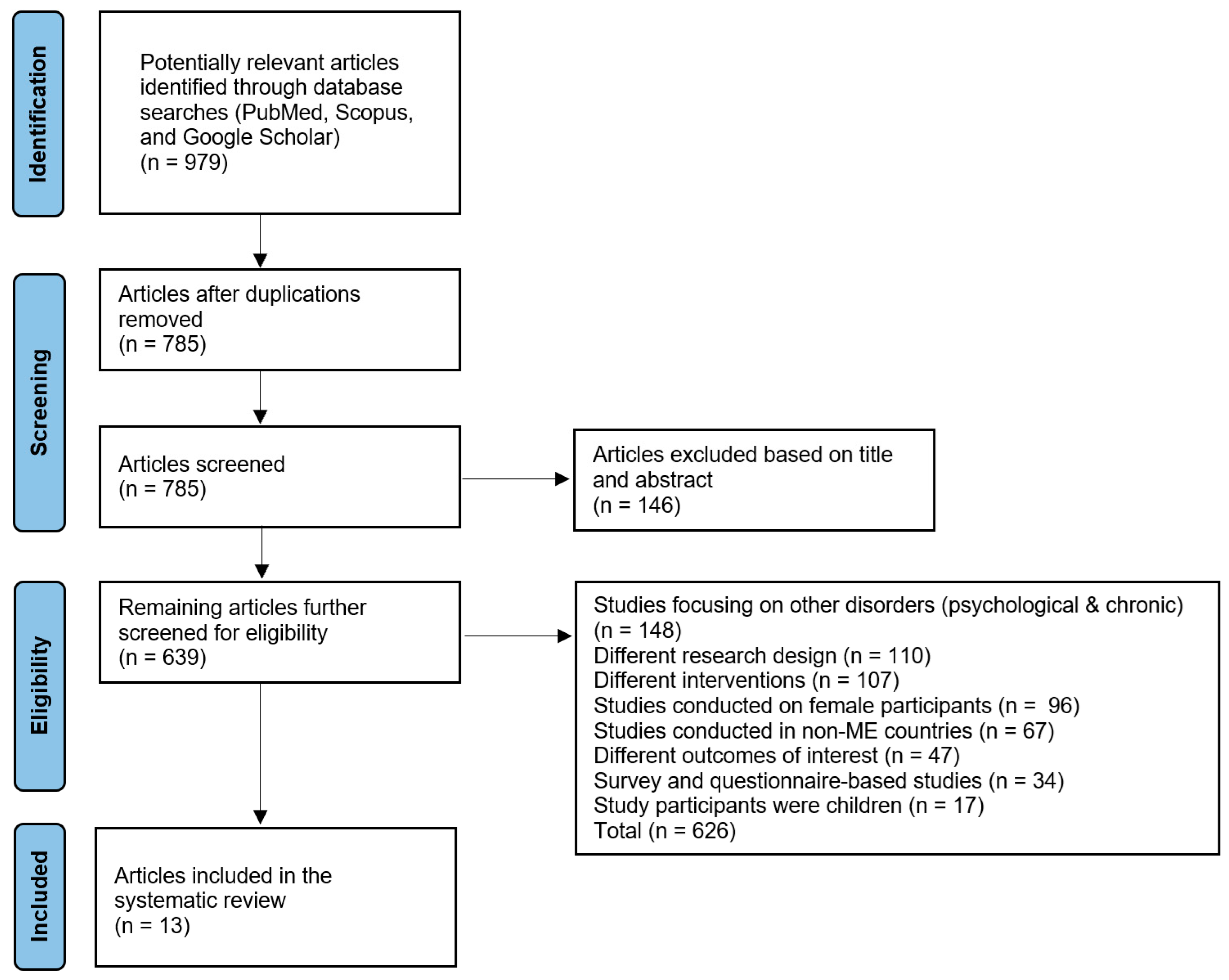

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

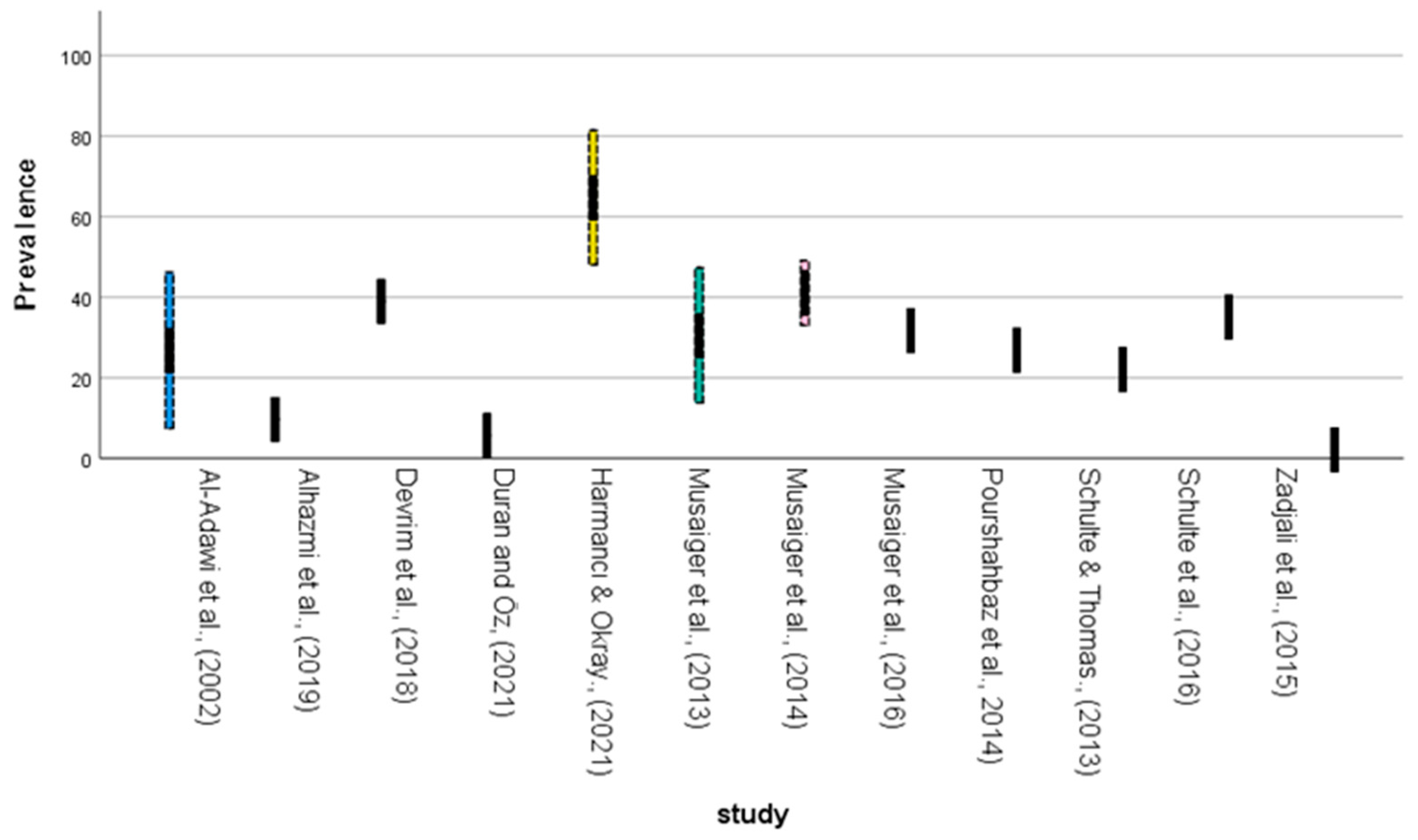

3.2. Prevalence Distribution and Geographic Patterns

3.2.1. Regional Prevalence Variations

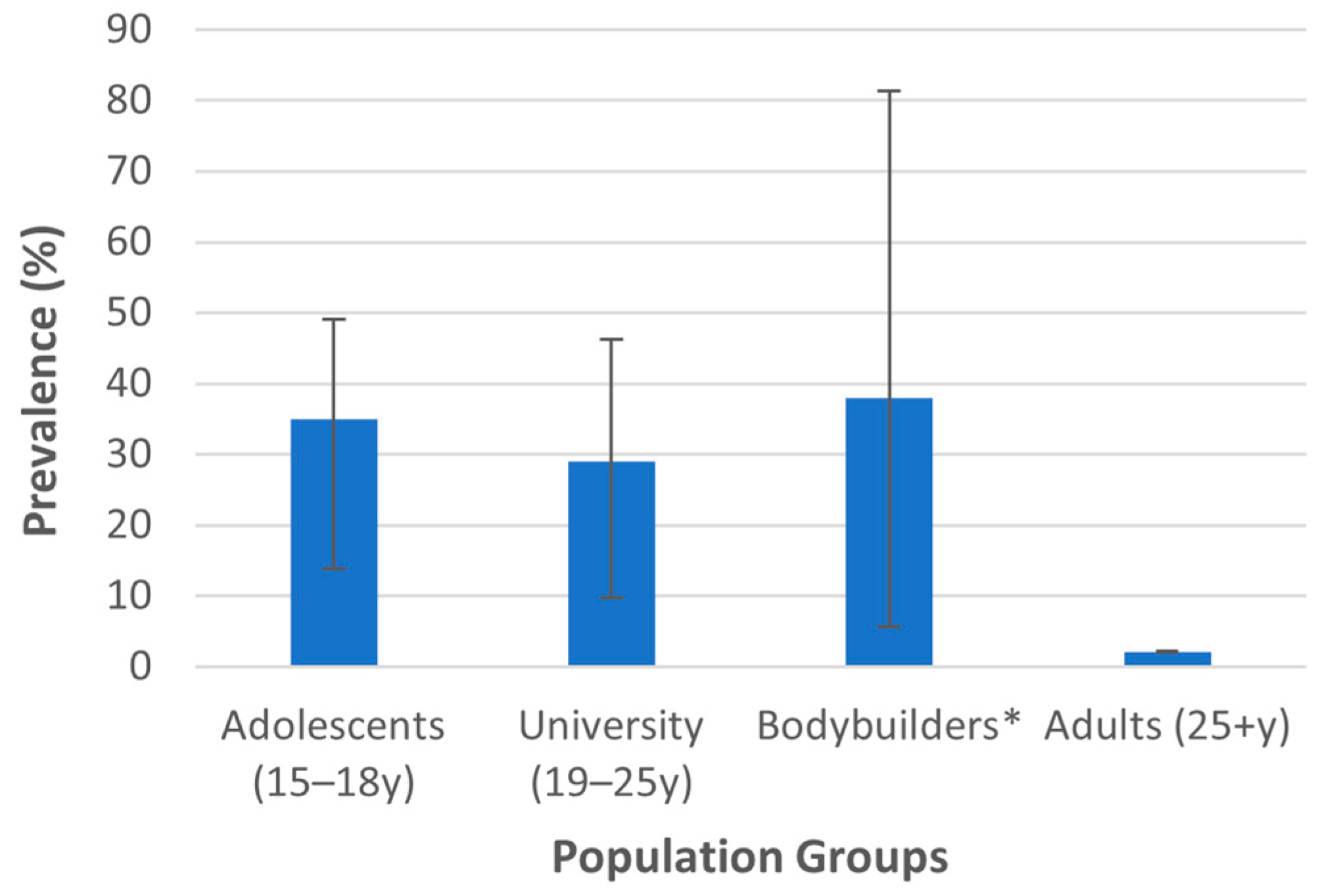

3.2.2. Population-Specific Prevalence Patterns

3.2.3. Age-Specific Prevalence Patterns

3.3. Diagnostic Categories and Clinical Presentations

3.3.1. Traditional Eating Disorders

3.3.2. Muscle Dysmorphia and Body Image Disorders

3.4. Assessment Methodology and Diagnostic Considerations

3.5. Risk Factors and Associated Variables

3.5.1. Demographic and Clinical Correlates

3.5.2. Psychological and Cultural Factors

3.6. Temporal Trends and Emerging Patterns

3.6.1. Increasing Prevalence over Time

3.6.2. Evolving Clinical Recognition

3.7. Quality and Limitations of Available Evidence

3.8. Summary of Key Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence Patterns and Regional Variations

4.2. Neurobiological Implications and Male-Specific Presentations

4.3. Cultural Transformation and Societal Influences

4.4. Risk Factors and Comorbidity Patterns

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Culturally Adapted Clinical Strategies and Prevention Programs

4.7. Methodological Quality and Diagnostic Consistency

4.8. Study Limitations

4.9. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AN | Anorexia nervosa |

| BED | Binge eating disorder |

| BN | Bulimia nervosa |

| ED | Eating disorder |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| MD | Muscle dysmorphia |

| NES | Night eating syndrome |

References

- Melisse, B.; de Beurs, E.; van Furth, E.F. Eating Disorders in the Arab World: A Literature Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devrim-Lanpir, A.; Zare, R.; Ali Redha, A.; Sandgren, S.S. Muscle Dysmorphia and Associated Psychological Features of Males in the Middle East: A Systematic Review. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2023, 11, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienke, C. Negotiating the Male Body: Men, Masculinity, and Cultural Ideals. J. Men’s Stud. 1998, 6, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Al Marzooqi, F.H.; Tahboub-Schulte, S.; Furber, S.W. Changing Physical Appearance Preferences in the United Arab Emirates. Ment. Heal. Relig. Cult. 2014, 17, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.M.; Hoek, H.W.; Dunne, P.E. Cultural Trends and Eating Disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.N.; Pumariega, A.J. Culture and Eating Disorders: A Historical and Cross-Cultural Review. Psychiatry 2001, 64, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, J.Y.; Cheon, B.K.; Pornpattananangkul, N.; Mrazek, A.J.; Blizinsky, K.D. Cultural Neuroscience: Progress and Promise. Psychol. Inq. 2013, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, C.O.; Scarpatto, C.; Garizábalo-Davila, C.M.; Valencia, P.A.D.; Irigaray, T.Q.; Cañon-Montañez, W.; Mattiello, R. Assessing Eating Disorder Symptoms in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Psychometric Studies of Commonly Used Instruments. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, B.; Poku, O.; Attoh-Okine, N.D.; Presskreischer, R. The Need for Epidemiological Research on Eating Disorders in Africa and the Caribbean. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 1688–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Duarte, T.A.; Schmidt, U. Eating Disorders. Lancet 2020, 395, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C.M.; Blake, L.; Austin, J. Genetics of Eating Disorders: What the Clinician Needs to Know. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, W.H.; Wierenga, C.E.; Bailer, U.F.; Simmons, A.N.; Bischoff-Grethe, A. Nothing Tastes as Good as Skinny Feels: The Neurobiology of Anorexia Nervosa. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinglass, J.E.; Berner, L.A.; Attia, E. Cognitive Neuroscience of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 42, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W. Advances from Neuroimaging Studies in Eating Disorders. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, B.; Touyz, S.; Hay, P.; Burton, A.; Russell, J.; Caterson, I. Neuroimaging in Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silén, Y.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Worldwide Prevalence of DSM-5 Eating Disorders among Young People. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z. Eating Disorders, DSM–5 and Clinical Reality. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerniglia, L. Neurobiological, Genetic, and Epigenetic Foundations of Eating Disorders in Youth. Children 2024, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinasz, K.; Accurso, E.C.; Kass, A.E.; Le Grange, D. Does Sex Matter in the Clinical Presentation of Eating Disorders in Youth? J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornborrow, T.; Onwuegbusi, T.; Mohamed, S.; Boothroyd, L.G.; Tovée, M.J. Muscles and the Media: A Natural Experiment Across Cultures in Men’s Body Image. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 501704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Brun, D.; Pescarini, E.; Calonaci, S.; Bonello, E.; Meneguzzo, P. Body Evaluation in Men: The Role of Body Weight Dissatisfaction in Appearance Evaluation, Eating, and Muscle Dysmorphia Psychopathology. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, T.M.; Neumann, D.L.; Seekis, V.; Dunn, M. Understanding Muscularity, Physique Anxiety, and the Experience of Body Image Enhancement among Men and Women: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 34, e2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, T.; Menchon, J.M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Fernandez-Aranda, F. Neural Network Alterations Across Eating Disorders: A Narrative Review of FMRI Studies. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 16, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, F.; Vignapiano, A.; Di Gruttola, B.; Landi, S.; Panarello, E.; Malvone, R.; Palermo, S.; Marenna, A.; Collantoni, E.; Celia, G.; et al. Neuroimaging and Machine Learning in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2025, 30, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.B.; Rieger, E.; Touyz, S.W.; García, Y.D.L.G. Muscle Dysmorphia and the DSM-V Conundrum: Where Does It Belong? A Review Paper. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganson, K.T.; Mitchison, D.; Rodgers, R.F.; Murray, S.B.; Testa, A.; Nagata, J.M. Prevalence and Correlates of Muscle Dysmorphia in a Sample of Boys and Men in Canada and the United States. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronleigh, M.; Baumann, O.; Stapleton, P. Neural Correlates Associated with Processing Food Stimuli in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa: An Activation Likelihood Estimation Meta-Analysis of FMRI Studies. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Fabris, M.A.; Longobardi, C. The Association between Muscle Dysmorphia and Eating Disorder Symptomatology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Gutchess, A. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Aging and Culture. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, A.; Berardi, N.; Maffei, L. Environment and Brain Plasticity: Towards an Endogenous Pharmacotherapy. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 189–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herb, M. The Wages of Oil: Parliaments and Economic Development in Kuwait and the UAE; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, A.; Bhatia, K. The Social Media Diet: A Scoping Review to Investigate the Association between Social Media, Body Image and Eating Disorders amongst Young People. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C. Exploring the Gene–Environment Nexus in Eating Disorders. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acle, A.; Cook, B.J.; Siegfried, N.; Beasley, T. Cultural Considerations in the Treatment of Eating Disorders among Racial/Ethnic Minorities: A Systematic Review. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2021, 52, 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.M. Special Report: Precision Psychiatry—Are We Getting Closer? Psychiatr. News 2022, 57, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, L.; Hubel, C.; Bulik, C.M. Updates on Genome-Wide Association Findings in Eating Disorders and Future Application to Precision Medicine. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, K.; Ceccarini, M.R.; Dhuli, K.; Bonetti, G.; Medori, M.C.; Marceddu, G.; Precone, V.; Xhufi, S.; Bushati, M.; Bozo, D.; et al. Gene Variants in Eating Disorders. Focus on Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, S.M.; Barnett, J.A.; Gibson, D.L. A Critical Analysis of Eating Disorders and the Gut Microbiome. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ai, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G. Neuroimaging Studies of Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Eating Disorders. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Kirmayer, L.J. Cultural Neuroscience and Psychopathology: Prospects for Cultural Psychiatry. Prog. Brain Res. 2009, 178, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erriu, M.; Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L. The Role of Family Relationships in Eating Disorders in Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshamy, F.; Hamadeh, A.; Billings, J.; Alyafei, A. Mental Illness and Help-Seeking Behaviours among Middle Eastern Cultures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Data. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambleton, A.; Pepin, G.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; Byrne, S.; et al. Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidities of Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review of the Literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaka, S.; Pokhrel, S.; Patel, A.; Sejdiu, A.; Taneja, S.; Vashist, S.; Arisoyin, A.; Bachu, A.K.; Rajaram Manoharan, S.V.R.; Mogallapu, R.; et al. Demographics, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Hospital Outcomes across Eating Disorder Types in Adolescents and Youth: Insights from US Hospitals Data. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 3, 1259038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, R.; Hyam, L.; Schmidt, U. Early Intervention for Eating Disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2024, 37, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, D.; Knoll, L.J.; Blakemore, S.J. Adolescence as a Sensitive Period of Brain Development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, D.A.; Mena, M.P. Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents: A Tailored and Integrative Treatment for Hispanic Youth. Fam. Process. 2009, 48, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, M.; Saeidi, P.; Naeim, M.; Kavand, R.; Shojaei, B.; Imannezhad, S.; Dehghani, D. Improving Mental Health Infrastructure across the Middle East. Asian J. Psychiatry 2024, 93, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender, J.M.; Brown, T.A.; Murray, S.B. Men, Muscles, and Eating Disorders: An Overview of Traditional and Muscularity-Oriented Disordered Eating. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Keel, P.K. Eating Disorders in Boys and Men. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 19, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadati, C.e.K.; Kassie, S.A.; Bertl, B.; Sidani, M.F.; Melad, M.A.W.; Ammar, A. Psychometric Properties of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) and the Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) Using a Heterogenous Clinical Sample from Arab Countries. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adawi, S.; Dorvlo, A.S.S.; Burke, D.T.; Al-Bahlani, S.; Martin, R.G.; Al-Ismaily, S. Presence and Severity of Anorexia and Bulimia among Male and Female Omani and Non-Omani Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, S.J.; Thomas, J. Relationship between Eating Pathology, Body Dissatisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Male and Female Adolescents in the United Arab Emirates. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Mannai, M.; Tayyem, R.; Al-Lalla, O.; Ali, E.Y.A.; Kalam, F.; Benhamed, M.M.; Saghir, S.; Halahleh, I.; Djoudi, Z.; et al. Risk of Disordered Eating Attitudes among Adolescents in Seven Arab Countries by Gender and Obesity: A Cross-Cultural Study. Appetite 2013, 60, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Mannai, M.; Al-Lalla, O. Risk of Disordered Eating Attitudes among Male Adolescents in Five Emirates of the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Kandari, F.I.; Al-Mannai, M.; Al-Faraj, A.M.; Bouriki, F.A.; Shehab, F.S.; Al-Dabous, L.A.; Al-Qalaf, W.B. Disordered Eating Attitudes among University Students in Kuwait: The Role of Gender and Obesity. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, E.M.; Grilo, C.M.; Gearhardt, A.N. Shared and Unique Mechanisms Underlying Binge Eating Disorder and Addictive Disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 44, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, A.H.; Al Johani, A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Eating Disorders among Students in Taiba University, Saudi Arabia: A Cross Sectional Study. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2019, 19, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, M.; Alkazemi, D.; Zafar, T.A.; Kubow, S. Disordered Eating Attitudes Correlate with Body Dissatisfaction among Kuwaiti Male College Students. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadjali, F.; Al-Bulushi, A.; AlHassani, F.; Al Hinai, M. Proportion of Night Eating Syndrome in Arab Population of Oman. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourshahbaz, A.; Nonahal, S.; Dolatshahi, B.; Omidian, M. The Role of the Media, Perfectionism, and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation in Prediction of Muscle Dysmorphia Symptoms. Pract. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 2, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Devrim, A.; Bilgic, P.; Hongu, N. Is There Any Relationship Between Body Image Perception, Eating Disorders, and Muscle Dysmorphic Disorders in Male Bodybuilders? Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 1746–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, S.; Öz, Y.C. Examination of the Association of Muscle Dysmorphia (Bigorexia) and Social Physique Anxiety in the Male Bodybuilders. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 1720–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subaşı Harmancı, B.; Okray, Z. Body Image, Muscle Dysmorphia and Narcissistic Characteristics of Bodybuilder Males in Trnc. Cyprus Turk. J. Psychiatry Psychol. 2021, 3, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official World Bank GDP per Capita Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Mahmood, H.; Asadov, A.; Tanveer, M.; Furqan, M.; Yu, Z. Impact of Oil Price, Economic Growth and Urbanization on CO2 Emissions in GCC Countries: Asymmetry Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, E. Cultural-Based Challenges of the Westernised Approach to Development in Newly Developed Societies. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Sharma, R.B.; Adow, A.H.E. An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship between Economic Growth, Urbanization, Energy Consumption, and CO2 Emission in GCC Countries: A Panel Data Analysis. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Scotto Rosato, M.; Desousa, A.; Cotrufo, P. Cultural Differences in Body Image: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Laveway, K.; Campos, P.; de Carvalho, P.H.B. Body Image as a Global Mental Health Concern. Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, U.R. Labor Migration, Remittances, and the Economy in the Gulf Cooperation Council Region. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSadrah, S.A. Social Media Use for Public Health Promotion in the Gulf Cooperation Council. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduosari, M.; Albuloshi, T.; Alsaber, A.; Al Saeed, F.; Alkandari, A.; Anbar, A.; Alboloushi, B.; Helmy, Y. Influence of Social Media on Cosmetic Facial Surgeries among Individuals in Kuwait: Employing the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1546128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, M.N.; Moustafa, A.R.A.; Azzam, H.; Bshar, A.M.; Ismail, I.S.; Elhadidy, O.Y. Association between Beauty Standards Shaped by Social Media and Body Dysmorphia among Egyptian Medical Students. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayan-Fadlelmula, F.; Sellami, A.; Abdelkader, N.; Umer, S. A Systematic Review of STEM Education Research in the GCC Countries: Trends, Gaps and Barriers. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalkrishnan, N. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Mousavi, S.E.; Karamzad, N.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Pirotta, S.; Collins, G.S.; Abdollahi, M.; Kolahi, A.A. Comparison of the Burden of Anorexia Nervosa in the Middle East and North Africa Region between 1990 and 2019. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C.M.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Hardaway, J.A.; Breithaupt, L.; Watson, H.J.; Bryant, C.D.; Breen, G. Genetics and Neurobiology of Eating Disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Park, J. Cultural Neuroscience of the Self: Understanding the Social Grounding of the Brain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2010, 5, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.C.; Huang, C.M. Culture Wires the Brain: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, L.A.; Brown, T.A.; Lavender, J.M.; Lopez, E.; Wierenga, C.E.; Kaye, W.H. Neuroendocrinology of Reward in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa: Beyond Leptin and Ghrelin. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 497, 110320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W.; Shott, M.E.; Stoddard, J.; Swindle, S.; Pryor, T.L. Association of Brain Reward Response with Body Mass Index and Ventral Striatal-Hypothalamic Circuitry among Young Women with Eating Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimerson, D.C.; Lesem, M.D.; Kaye, W.H.; Hegg, A.P.; Brewerton, T.D. Eating Disorders and Depression: Is There a Serotonin Connection? Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 28, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisman, H.; Merali, Z.; Poulter, M.O. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Involvement in Depressive Illness Interactions with Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone and Serotonin. In The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonderlich, J.A.; Bershad, M.; Steinglass, J.E. Exploring Neural Mechanisms Related to Cognitive Control, Reward, and Affect in Eating Disorders: A Narrative Review of FMRI Studies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmeed, M.B.; Almutawa, M.A.; Naguib, Y.M. The Prevalence of and the Effect of Global Stressors on Eating Disorders among Medical Students. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1507910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakhil, L.O.; Abaalkhail, B.A.; Abu, I.I. Influence of Sociocultural Factors on the Risk of Eating Disorders among King Abdulaziz University Students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2022, 29, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoez, J. Muscles, Moustaches and Machismo: Narratives of Masculinity by Egyptian English-Language Media Professionals and Media Audiences. Masculinities J. Identity Cult. 2018, 9–10, 198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, B.J.; Cornelissen, P.L.; Maalin, N.; Mohamed, S.; Kramer, R.S.S.; McCarty, K.; Tovée, M.J. The Degree to Which the Cultural Ideal Is Internalized Predicts Judgments of Male and Female Physical Attractiveness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 980277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasson, J.; Johansson, T. The Fitness Revolution: Historical Transformations in the Global Gym and Fitness Culture. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 23, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaidan, M.S.; Altayar, N.S.; Alshmmari, S.H.; Alshammari, M.M.; Alqahtani, F.T.; Mohajer, K.A. The Prevalence and Determinants of Body Dysmorphic Disorder among Young Social Media Users: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol. Rep. 2020, 12, 8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Cocks, A.J.; Hills, L.; Kerner, C. Active and Passive Social Media Use: Relationships with Body Image in Physically Active Men. New Media Soc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Hobiger, S.; Jungbauer, A. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Extracts from Fruits, Herbs and Spices. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Zanetti, A.M.; Riva, G.; Colmegna, F.; Volpato, C.; Madeddu, F.; Clerici, M. Male Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disorder Symptomatology: Moderating Variables Among Men. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.B.; Haynos, A.F.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Fifteen-Year Prevalence, Trajectories, and Predictors of Body Dissatisfaction From Adolescence to Middle Adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawed, A.; Harrison, A.; Dimitriou, D. The Presentation of Eating Disorders in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 586706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, C.L.; Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Kvalem, I.L.; Wennersberg, A.L.; Wisting, L. Further Evidence of the Association between Social Media Use, Eating Disorder Pathology and Appearance Ideals and Pressure: A Cross-Sectional Study in Norwegian Adolescents. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbeisen, G.; Laskowski, N.; Brandt, G.; Waschescio, U.; Paslakis, G. Eating Disorders in Men: An Underestimated Problem, an Unseen Need. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2024, 121, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaba, L.; D’Arripe-Longueville, F.; Scoffier-Mériaux, S.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V. Investigation of Eating and Deviant Behaviors in Bodybuilders According to Their Competitive Engagement. Deviant Behav. 2019, 40, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, T.A.; Mandeel, Q.A.; Al-Sarhani, L. Traditional Plant-Based Foods and Beverages in Bahrain. J. Ethn. Foods 2017, 4, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, M.; Henry, D.B. Shared Understanding as a Gateway for Treatment Engagement: A Preliminary Study Examining the Effectiveness of the Culturally Enhanced Video Feedback Engagement Intervention. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, L.E.; Hook, J.N.; Hoyt, W.; Davis, D.E.; McElroy-Heltzel, S.E.; Worthington, E.L. Integrating Clients’ Religion and Spirituality within Psychotherapy: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Dawes, A.J.; Rice, S.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, H.M. The Role of Masculinity in Men’s Help-Seeking for Depression: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.B.; Plasencia, M.; Kilpela, L.S.; Briggs, M.; Stewart, T. Changing the Course of Comorbid Eating Disorders and Depression: What Is the Role of Public Health Interventions in Targeting Shared Risk Factors? J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.K.D.; Barendregt, J.J.; Hay, P.; Mihalopoulos, C. Prevention of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 53, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlett, C.P.; Vowels, C.L.; Saucier, D.A. Meta-Analyses of the Effects of Media Images on Men’s Body-Image Concerns. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 27, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Druss, B.G.; Perlick, D.A. The Impact of Mental Illness Stigma on Seeking and Participating in Mental Health Care. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2014, 15, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Eating Disorders in Athletes: Overview of Prevalence, Risk Factors and Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; McManus, S.; Jessop, C.; John, A.; Hotopf, M.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Wessely, S.; Abel, K.M. Says Who? The Significance of Sampling in Mental Health Surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifman, S.; DeVost, M.A.; Digitale, J.C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Morris, M.D. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A Sampling Method for Hard-to-Reach Populations and Beyond. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2022, 9, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assa’ad, A.; Hershko, A.Y.; Irani, C.; Mahdavinia, M.; Khan, D.A.; Bernstein, J.A. Health Disparities in the Middle East: Representative Analysis of the Region. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2025, 4, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, P.K.; Klump, K.L. Are Eating Disorders Culture-Bound Syndromes? Implications for Conceptualizing Their Etiology. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.E.; Basten, C.J.; McAloon, J. The Development of Disordered Eating in Male Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Prospective Longitudinal Studies. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2024, 9, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Males aged ≥ 15 years in Middle East countries |

| Intervention | EAT-26, BES, PSS, ESS, WEB-SG, OCI-R, ZSRDS, FRS, BDI-II, NEQ, MDDI, DFS, AI, FI, MPS, SATAQ-3, DERS, EAT-40, BIG, MDI, NPI, BITE, and BIS |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcome | ED prevalence (AN, BN, BED, MD, NES, UFED, and other ED presentations) |

| Study design | Cross-sectional, original articles, and reviews |

| First Author, Year | Country | Population Type | n (Males) | Assessment Tools | ED Type | Male Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Adawi, 2002 [53] | Oman | Students & adults | 145 | EAT-26, BITE | AN, BN | EAT-26: 36.4% (Omani), 7.5% (Non-Omani); BITE: 10.9% (Omani), 32.5% (Non-Omani); Adults: 2% |

| Schulte, 2019 [54] | UAE | Undergraduates | 71 | EAT-26, FRS, BDI-II | ED | 22% |

| Musaiger, 2013 [55] | Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Palestine, Syria, UAE | Adolescents (15–18 y) | 2240 | EAT-26 | ED | 13.8% to 47.3% |

| Musaiger, 2014 [56] | UAE | Students (15–18 y) | 731 | EAT-26 | ED | 33.1% to 49.1% |

| Musaiger, 2016 [57] | Kuwait | University students | 203 | EAT-26 | ED | 31.8% |

| Schulte, 2016 [58] | UAE | Undergraduates | 236 | BES, PSS, ESS, WEB-SG, OCI-R, ZSRDS | BED | 35.2% |

| Alhazmi, 2019 [59] | Saudi Arabia | University students | 171 | EAT-26 | ED | 9.7% |

| Ebrahim, 2019 [60] | Kuwait | Undergraduates (84.8% Kuwaiti) | 400 | EAT-26 | ED | 46.2% |

| Zadjali, 2015 [61] | Oman | Staff & students (≥20 y) | 231 | NEQ | NES | 2.2% |

| Pourshahbaz, 2014 [62] | Iran | Bodybuilders | 240 | MDDI, MPS, SATAQ-3, DERS | MD | 26.9% |

| Devrim, 2018 [63] | Turkey | Bodybuilders | 120 | EAT-40, BIG, MDDI | ED | 39% |

| Duran, 2022 [64] | Turkey | Bodybuilders | 384 | MDDI, DFS, AI, FI, Social Physique Anxiety | MD | 5.7% |

| Harmancı, 2021 [65] | Turkey | Bodybuilders vs. controls | 128 (63 BB, 65 controls) | MDI, NPI, BIS | MD | BBs: 81.4%; Controls: 48.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alalwan, T.A.; Perna, S.; Rafique, A.; Allehdan, S.; Cioffi, I.; Rondanelli, M. The Hidden Challenge: Male Eating Disorders in the Middle East: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Cultural Factors. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030115

Alalwan TA, Perna S, Rafique A, Allehdan S, Cioffi I, Rondanelli M. The Hidden Challenge: Male Eating Disorders in the Middle East: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Cultural Factors. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030115

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlalwan, Tariq A., Simone Perna, Ayesha Rafique, Sabika Allehdan, Iolanda Cioffi, and Mariangela Rondanelli. 2025. "The Hidden Challenge: Male Eating Disorders in the Middle East: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Cultural Factors" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030115

APA StyleAlalwan, T. A., Perna, S., Rafique, A., Allehdan, S., Cioffi, I., & Rondanelli, M. (2025). The Hidden Challenge: Male Eating Disorders in the Middle East: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Cultural Factors. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030115