Complications and Comorbidities in Individuals >80 Years with Diabetes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Types of Studies and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Process of Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

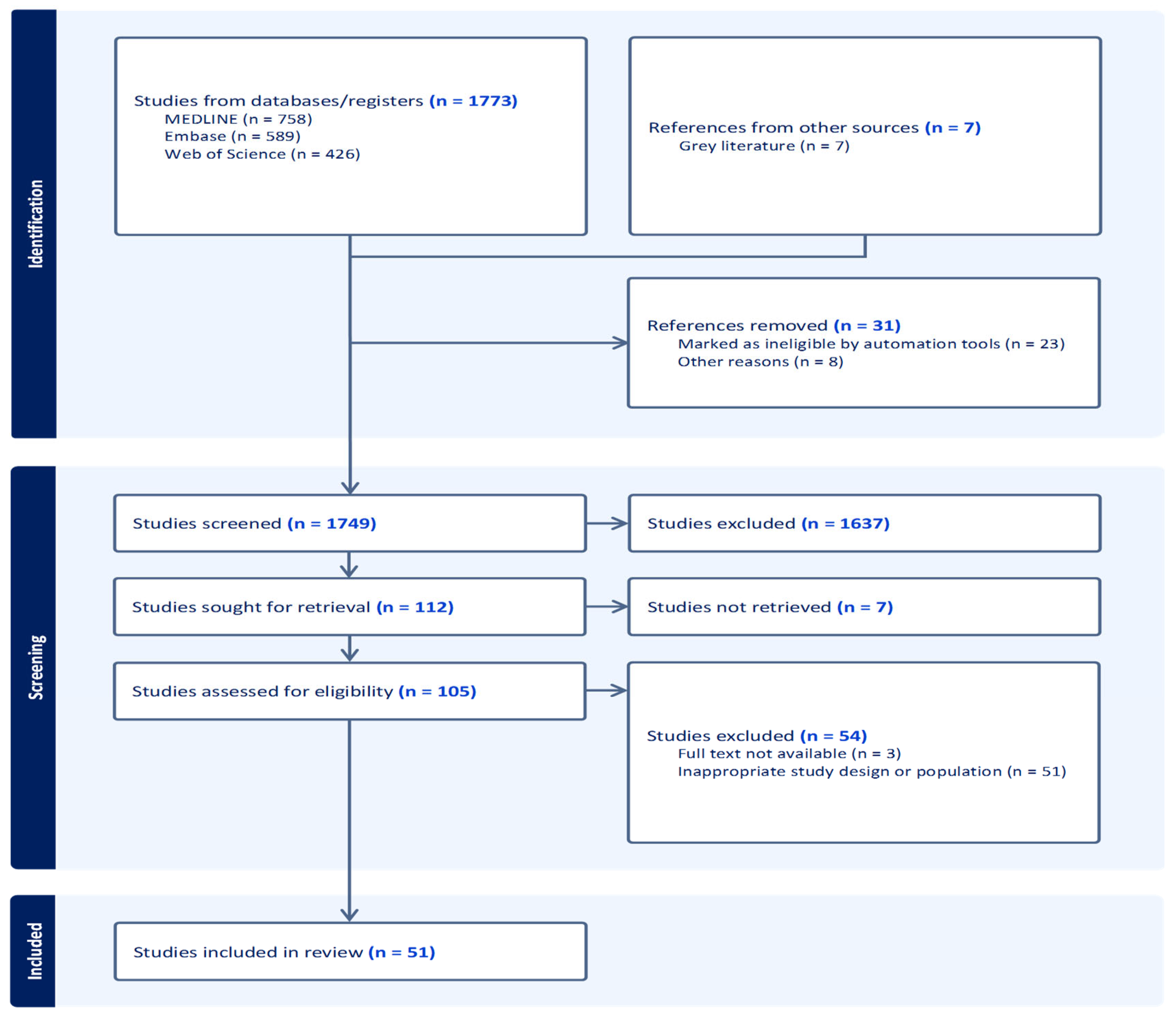

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Macrovascular Complications

3.4. Microvascular Complications

3.5. Peripheral Complications

3.6. Other Comorbidities

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Interpretation

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| DN | Diabetic Neuropathy |

| ESRD | End-Stage Renal Disease |

| HIC | High-Income Country |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| ISH | Isolated Systolic Hypertension |

| LMIC | Low-Middle Income Country |

| TIA | Transient Ischaemic Attack |

| T1DM | Type-1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T2DM | Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

Appendix A

| Authors | Country | Study Design | Mean Age (Years) | Total Sample Size | Participants Aged 80+ with Diabetes (Overall) | Reported Outcomes in Study (T1DM, T2DM) | Complication (%) |

| Sinclair 2008 [19] | UK | Population-based case–control study | 75 | 806 | 90 | Both | CVD(15.5%) Stroke(17.1%) PAD(28.2%) HTN(30.1%) DN(35.1%) |

| Chang 2021 [59] | South Korea | Retrospective cohort study | 70 | 18,567 | 2708 | Both | Stroke(10%) |

| Jie 2021 [60] | Malaysia | Retrospective cohort study | 65.6 | 179,210 | 3325 | Both | CVD(8.7%) Stroke(1.2%) HTN(63%) |

| Sukkar 2020 [61] | Australia | Retrospective cohort study | 65.4 | 9313 | 80 | Both | Stroke(4.8%) HTN(73.4%) Obesity(43.5%) |

| Gershater 2021 [43] | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study | 81 | 1008 | 500 | Both | CVD(13.7%) DR(13.2%) Amputation(2.6%) DN(6.6%) |

| Yotsapon 2016 [62] | Thailand | Retrospective cohort study | 87 | 2859 | 266 | Both | Stroke(18%) PAD(19.5%) DR(16.5%) CKD(55%) |

| Tanasescu 2023 [63] | Romania | Retrospective cohort study | n/A | 228 | 20 | Both | CVD(45%) Stroke(10%) Obesity(55%) Amputation(70%) |

| Sattar 2019 [64] | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study | 61.8 | 241,278 | 5449 | Both | CVD(1.3%) Stroke(1.43%) Amputations(0.1%) |

| Kissela 2005 [65] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 72 | 4664 | 4264 | Both | CVD(22%) Stroke(100%) HTN(79%) |

| Bertoni 2005 [66] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 74 | 144,115 | 32,040 | Both | CVD(20.7%) DR(17.1%) HTN(71.5%) DN(17%) |

| Hangaard 2019 [67] | Denmark | Retrospective cohort study | n/A | 12,701 | 836 | Both | CVD(30.5%) Foot ulcer (0.5%) Obesity (54%) |

| Chima 2017 [68] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | n/A | 82,767,321 | 16,557,870 | Both | CVD(27%)(38.9%) * HTN(55%)(75%) * CKD(17.3%)(19.1%) * |

| Clau-Espuny 2017 [69] | Spain | Retrospective cohort study | 81.2 | 932 | 315 | Both | HTN(84.1%) PAD(13.9%) Stroke(28.3%) |

| Huang 2014 [70] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 71 | 72,310 | 10,846 | T2DM | CVD(87.3%) Stroke(21%) PAD(22.2%) DN(3.4%) |

| DPV Initiative 2012 [71] | Germany; Austria | Retrospective cohort study | 67.1 | 120,183 | 17,353 | T2DM | DR(15.6%) HTN(26.9%) |

| Wong 2024 [72] | Malaysia | Retrospective cohort study | 81.1 | 384 | 384 | T2DM | CVD(27.2%) Stroke(100%) HTN(90.8%) |

| Win 2016 [73] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 72.6 | 1014,879 | 265,766 | T2DM | CVD(25.3%) |

| Alonso-Moran 2014 [74] | Spain | Retrospective cohort study | n/A | 134,421 | 48,407 | T2DM | CVD(4.3%) Stroke(7%) DR(7.2%) DN(1.3%) |

| C. LI. Morgan 1999 [75] | UK | Retrospective cohort study | 61.5 | 10,287 | 112 | T2DM | CVD(40%) Stroke(20%) DR(19%) Diabetic Foot(21%) Nephropathy(4%) |

| Bong-Ki Lee 2016 [76] | South Korea | Retrospective cohort study | 83.2 | 289 | 289 | T2DM | HTN(75.1%) Stroke(17%) DR(33.5%) |

| Tang 2020 [77] | USA | Prospective cohort study | 75.5 | 5791 | 852 | Both | CVD(36.4%) HTN(91.8%) Obesity(49.2%) |

| Gual 2020 [78] | Spain | Prospective cohort study | 63.1 | 12,792 | 1720 | Both | CVD(11.1%) Stroke(4.4%) HTN(27.6%) |

| Regidor 2012 [79] | Spain | Prospective cohort study | n/A | 4008 | 132 | Both | CVD(18.1%) Stroke(6.6%) HTN(71%) |

| Apelqvist 1992 [80] | Sweden | Prospective cohort study | 70 | 314 | 47 | Both | DR(29.6%) Nephropathy(22.2%) |

| Andrew J. Karter 2015 [81] | USA | Prospective cohort study | 72 | 115,538 | 22,058 | Both | Stroke(1%) DR(21%) ESRD(2%) |

| Huang 2023 [82] | USA | Prospective cohort study | 74.3 | 105,786 | 23,273 | T2DM | CVD(18.2%) Stroke(4.9%) PAD(17.4%) HTN(91.1%) DN(8%) Obesity(44.2%) |

| Morton 2022 [83] | Australia | Prospective cohort study | n/A | 1,235,759 | 246,261 | T2DM | CVD(45.5%) Stroke(3.6%) PAD(6.2%) ESRD(14%) |

| Beard 2009 [84] | USA | Population-based study | 81 | 2034 | 540 | Both | CVD(74%) DR(55.1%) HTN(71.4%) Obesity(70%) |

| Huang 2015 [85] | Taiwan | Population-based study | 71 | 13,551 | 1290 | Both | Stroke(17.2%) HTN(59%) |

| MacDonald 2008 [86] | UK | Population-based study | 75 | 116,556 | 6504 | Both | CVD(53.4%) Stroke(32.9%) PAD(38%) |

| Klein 2002 [87] | USA | Population-based study | 78.5 | 296 | 81 | Both | DR(16%) |

| Wang 2020 [88] | China | Population-based study | 67 | 3205 | 119 | T2DM | Stroke(21.9%) |

| Wingard 1993 [89] | USA | Population-based study | 70 | 2234 | 335 | T2DM | CVD(51.1%) Stroke(29.5%) PAD(12.6%) |

| Jedidiah I. Morton 2022 [90] | Australia | Population-based study | 70.2 | 1,160,155 | 253,336 | T2DM | CVD(13.9%) Stroke (3.5%) |

| Olesen 2022 [91] | Denmark | Population-based study | 59 | 383,325 | 34,996 | T2DM | CVD(6.3%) Stroke(5%) Obesity(21%) |

| Lee 2023 [92] | South Korea | Cross-sectional study | 72 | 116 | 24 | Both | CVD(50%) HTN(79%) DR(100%) |

| Ferrer 2012 [93] | Spain | Cross-sectional study | 85 | 328 | 328 | Both | CVD(30.6%) Stroke(14%) HTN(89.4%) |

| Kalyani 2010 [94] | USA | Cross-sectional study | 70.4 | 6097 | 156 | Both | CVD(45%) Stroke(14%) PAD(21%) HTN(71.8%) DN(34%) CKD(74%) |

| Barrio-Cortes 2024 [95] | Spain | Cross-sectional study | 70 | 1063 | 439 | Both | CVD (12.2%) Stroke(6.1%) HTN(70%) Obesity(32.4%) CKD(5.8%) |

| VanMark 2020 [96] | Germany | Cross-sectional study | 70.8 | 396,719 | 80,643 | T2DM | Stroke(25.1%) PAD(17.1%) DR(28.8%) HTN(77%) DN(40.8%) Obesity(31.7%) CKD(73.1%) |

| Sazlina 2014 [97] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional study | 71.3 | 10,363 | 875 | T2DM | CVD(11.4%) Stroke(12%) DR(9%) HTN(41.6%) Nephropathy(12.3%) |

| Mok 2019 [98] | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional study | 65.3 | 35,109 | 4134 | T2DM | DR(36%) HTN(81%) DN(9.7%) Obesity(53.2%) Nephropathy(31.6%) |

| Yau 2012 [99] | USA | Longitudinal cohort study | 80 | 367 | 367 | Both | CVD(34%) ESRD(5%) |

| Weiss 2009 [100] | Israel | Longitudinal cohort study | 79 | 121 | 60 | Both | CVD(6.7%) Stroke(36.7%) HTN(56.7%) |

| Rodriguez-Saldana 2002 [101] | Mexico | Longitudinal cohort study | n/A | 785 | 11 | Both | Stroke(8.4%) HTN(74%) Obesity(32%) |

| Sinclair 2000 [102] | UK | Case–control study | n/A | 770 | 40 | Both | DR(40%) |

| Shen 2023 [103] | China | Case–control study | 81.5 | 231 | 231 | Both | CVD(35%) Stroke(22%) HTN(86.6%) CKD(37%) |

| Hirakawa 2017 [29] | Japan | Observational cohort study | 58 | 38,854 | 417 | Both | CVD(8%) Stroke(3%) |

| Benbow 1997 [104] | UK | Observational cohort study | 80.9 | 1611 | 109 | Both | Stroke(21%) PAD(33.1%) DN(18.3%) |

| Orces 2018 [105] | Ecuador | Cross-sectional, population-based survey | 71.6 | 2298 | 308 | T1DM | HTN(53.8%) |

| Schutt 2012 [106] | Germany and Austria | Observational, cross-sectional analysis | 22.8 | 64,609 | 377 | T1DM | CVD(10.1%) Stroke(7.7%) DR(41.4%) HTN(31.2%) |

References

- Dall, T.M.; Yang, W.; Gillespie, K.; Mocarski, M.; Byrne, E.; Cintina, I.; Beronji, K.; Semilla, P.A.; Iacobucci, W.; Hogan, P.F. The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2017: Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Coon, J.T.; Bethel, A.; Rogers, M.; Whear, R.; Orr, N.; Garside, A.; Goodwin, V.; Mahmoud, A.; Lourida, I.; et al. PROTOCOL: Health and social care interventions in the 80 years old and over population: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2023, 19, e1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Crus, J.A.; Hagins, H.; Lindstedt, P.A.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/5174879e-b0dc-43fc-b3a8-b1db31c51d4c/content (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Bradley, D.; Hsueh, W.A. Type 2 Diabetes in the Elderly: Challenges in a Unique Patient Population. J. Geriatr. Med. Gerontol. 2016, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Ke, C.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellary, S.; Kyrou, I.; Brown, J.E.; Bailey, C.J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: Clinical considerations and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakaryılmaz, F.D.; Öztürk, Z.A. Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly. World J. Diabetes 2017, 8, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouhi, N.G.; Wareham, N.J. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine 2014, 42, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Halter, J.B. The Pathophysiology of Hyperglycemia in Older Adults: Clinical Considerations. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M. Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, G.M. Role of Insulin Resistance in Human Disease. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Vallejo, S.; Peiró, C.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F.; Podríguez-Mañas, L. Mechanisms Involved in the Aging-Induced Vascular Dysfunction. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rask-Madsen, C.; King, G.L. Vascular Complications of Diabetes: Mechanisms of Injury and Protective Factors. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D.; Scantlebury, T.; Cianflone, K. Hypertriglyceridemic HyperapoB: The Unappreciated Atherogenic Dyslipoproteinemia in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 135, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chentli, F.; Azzoug, S.; Mahgoun, S. Diabetes mellitus in elderly. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 19, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Abdelhafiz, A.H. Challenges and Strategies for Diabetes Management in Community-Living Older Adults. Diabetes Spectr. 2020, 33, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Conroy, S.; Bayer, A. Impact of Diabetes on Physical Function in Older People. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, E.; Wongrakpanich, S.; Munshi, M. Diabetes Management in the Elderly. Diabetes Spectr. 2018, 31, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, M.S.; Briscoe, V.J.; Clark, N.; Flórez, H.; Haas, L.B.; Halter, J.B.; Huang, E.S.; Korytkowski, M.T.; Munshi, M.N.; Odegard, P.S.; et al. Diabetes in Older Adults. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2650–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, P.; Jani, B.D.; Butterly, E.; Nicholl, B.I.; Lewsey, J.; McAllister, D.A.; Mair, F.S. An analysis of frailty and multimorbidity in 20,566 UK Biobank participants with type 2 diabetes. Commun. Med. 2021, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriere, M.D.; Rooparinesingh, N.; Kalyani, R.R. Epidemiology of Diabetes and Diabetes Complications in the Elderly: An Emerging Public Health Burden. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013, 13, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, P.; Fauré, I.; Corcoran, N.; Butterly, E.; Lewsey, J.; McAllister, D.; Mair, F.S. Frailty measurement, prevalence, incidence, and clinical implications in people with diabetes: A systematic review and study-level meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020, 1, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, K.A.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mehran, R.; Nissen, S.E.; Wiviott, S.D.; Dunn, B.; Soloman, S.D.; Marler, J.R.; Teerlink, J.R.; Farb, A.; et al. 2017 Cardiovascular and Stroke Endpoint Definitions for Clinical Trials. Circulation 2018, 137, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Kiyohara, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Saitoh, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Okayama, K.; Tamakoshi, A.; Sakata, K.; Miura, K.; et al. Age-specific impact of diabetes mellitus on the risk of cardiovascular mortality: An overview from the evidence for Cardiovascular Prevention from Observational Cohorts in the Japan Research Group (EPOCH-JAPAN). J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Lou, Y.; Gu, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Ning, X.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; et al. Mortality, Recurrence, and Dependency Rates Are Higher after Acute Ischemic Stroke in Elderly Patients with Diabetes Compared to Younger Patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, J.; Mykkänen, L.; Pyörälä, K.; Laakso, M. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes and its metabolic control are important predictors of stroke in elderly subjects. Stroke 1994, 25, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajati, F.; Rajati, M.; Rasulehvandi, R.; Kazeminia, M. Prevalence of stroke in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2023, 32, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, A.; Barber, P.A. The Cognitive Sequelae of Transient Ischemic Attacks—Recent Insights and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, M.J.; Khan, S.K.A.; Pappachan, J.M.; Jeeyavudeen, M.S. Diabetes and cognitive function: An evidence-based current perspective. World J. Diabetes 2023, 14, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Lu, P. Correlations among Diabetic Microvascular Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umanath, K.; Lewis, J.B. Update on Diabetic Nephropathy: Core Curriculum 2018. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.; Yu, M.; Chee, M.L.; Rim, T.H.; Cheung, N.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, H.; MacGilchrist, C.; Kirwan, E.; McIntosh, C. Prevalence and risk factors of painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 205, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Lan, H.H.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Cao, P. Diabetic neuropathy: Cutting-edge research and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropp, M.; Golubnitschaja, O.; Mazuráková, A.; Koklesová, L.; Sargheini, N.; Vo, T.-T.K.S.; de Clark, E.; Polivka Jr, J.; Potuznik, P.; Polivka, J.; et al. Diabetic retinopathy as the leading cause of blindness and early predictor of cascading complications—Risks and mitigation. EPMA J. 2023, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzatvar, Y.; García-Hermoso, A. Global estimates of diabetes-related amputations incidence in 2010–2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 195, 110194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershater, M.A.; Apelqvist, J. Elderly individuals with diabetes and foot ulcer have a probability for healing despite extensive comorbidity and dependency. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2021, 21, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyoye, D.; Abiodun, O.O.; Ikem, R.T.; Kolawole, B.; Akintomide, A.O. Diabetes and peripheral artery disease: A review. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.S.M.; Saratzis, A.; Sayers, R.; Haunton, V.J. New Horizons in Peripheral Artery Disease. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.G.R.; Thorogood, M.; Connor, M.; Lewando-Hundt, G.; Tzoulaki, I.; Tollman, S. Distribution of a subclinical marker of cardiovascular risk, the ankle brachial index, in a rural African population: SASPI study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2006, 13, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehler, M.R.; Duval, S.; Diao, L.; Annex, B.H.; Hiatt, W.R.; Rogers, K.; Zakharyan, A.; Hirsch, A.T. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Evans, J.C.; Levy, D. Hypertension in Adults Across the Age Spectrum. JAMA 2005, 294, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, E.L. Vascular stiffening and arterial compliance: Implications for systolic blood pressure. Am. J. Hypertens. 2004, 17, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimploulis, A.; Sheriff, H.; Lam, P.H.; Dooley, D.J.; Anker, M.S.; Papademetriou, V.; Fletcher, R.S.; Faselis, C.; Fonarow, G.C.; Deedwania, P.; et al. Systolic–diastolic hypertension versus isolated systolic hypertension and incident heart failure in older adults: Insights from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 235, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravender, R.; Roumelioti, M.; Schmidt, D.W.; Unruh, M.; Argyropoulos, C. Chronic Kidney Disease in the Older Adult Patient with Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Juncos, L.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, M.E.; do Carmo, J.; da Silva, A.A. Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2014, 7, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Karabetian, C.; Naugle, K.M.; Buford, T.W. Obesity and diabetes as accelerators of functional decline: Can lifestyle interventions maintain functional status in high risk older adults? Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagenais, G.R.; Gerstein, H.C.; Zhang, X.; McQueen, M.; Lear, S.A.; López-Jaramillo, P.; Mohan, V.; Mony, P.; Gupta, R.; Kutty, V.R.; et al. Variations in Diabetes Prevalence in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: Results From the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.E.; Wijeweera, C.; Wijeweera, A. Lifestyle and socioeconomic determinants of diabetes: Evidence from country-level data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mybanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanakis, E.K.; Golden, S.H. Race/Ethnic Difference in Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013, 13, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.Y.; Kim, W.J.; Kwon, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.T.; Lee, J.; Cha, J.K.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, Y.J.; et al. Association of Prestroke Glycemic Control With Vascular Events During 1-Year Follow-up. Neurology 2021, 97, e2030–e2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Salowi, M.A.; Adnan, T.H.; Anuar, N.A.; Ngah, N.F.; Choo, M.M. Visual outcomes after Phacoemulsification with Intraocular Implantation surgeries among patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus. Med. J. Malays. 2021, 76, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sukkar, L.; Kang, A.; Hockham, C.; Young, T.K.; Jun, M.; Foote, C.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Neuen, B.; Rogers, K.; Pollack, C.; et al. Incidence and Associations of Chronic Kidney Disease in Community Participants With Diabetes: A 5-Year Prospective Analysis of the EXTEND45 Study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewjitcharoen, Y.; Krittiyawong, S.; Ekgaluck, W.; Vongterapak, S.; Tawee, A.; Worawit, K.; Soontaree, N.; Tawee, A.; Worawit, K.; Soontaree, N.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of the oldest old people with type 2 diabetes—Perspective from a tertiary diabetes center in Thailand. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2016, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tănăsescu, D.; Sabău, D.; Moisin, A.; Gherman, C.; Fleacă, R.; Băcilă, C.; Mohor, C.; Tanasescu, C. Risk assessment of amputation in patients with diabetic foot. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 25, 11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Rawshani, A.; Franzén, S.; Rawshani, A.; Svensson, A.; Rosengren, A.; McGuire, D.K.; Eliasson, B.; Gudbjornsdottir, S. Age at Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Associations With Cardiovascular and Mortality Risks. Circulation 2019, 139, 2228–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissela, B.; Khoury, J.; Kleindorfer, D.; Woo, D.; Schneider, A.; Alwell, K.; Miller, R.; Ewing, I.; Moomaw, C.J.; Szaflarski, J.P.; et al. Epidemiology of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoni, A.G.; Kirk, J.K.; Case, L.D.; Kay, C.; Goff, D.C.; Narayan, K.M.V.; Bell, R.A. The Effects of Race and Region on Cardiovascular Morbidity Among Elderly Americans With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2620–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangaard, S.; Rasmussen, A.; Almdal, T.; Nielsen, A.A.; Nielsen, K.E.; Siersma, V.; Holstein, P. Standard complication screening information can be used for risk assessment for first time foot ulcer among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 151, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chima, C.C.; Salemi, J.L.; Wang, M.; Grubb, M.C.M.; Gonzalez, S.J.; Zoorob, R. Multimorbidity is associated with increased rates of depression in patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in the United States. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clua-Espuny, J.L.; González-Henares, M.A.; Queralt-Tomas, M.L.; Campo-Tamayo, W.; Muria-Subirats, E.; Panisello-Tafalla, A.; Lucas-Noll, J. Mortality and Cardiovascular Complications in Older Complex Chronic Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6078498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, E.S.; Laiteerapong, N.; Liu, J.Y.; John, P.M.; Moffet, H.H.; Karter, A.J. Rates of Complications and Mortality in Older Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, W.L.; Fach, E.-M.; Krakow, D.; Welp, R.; Kunder, J.; Voll, A.; Zeyfang, A.; Wagner, C.; Schutt, M.; Boehm, B.; et al. Type 2 diabetes from pediatric to geriatric age: Analysis of gender and obesity among 120,183 patients from the German/Austrian DPV database. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 167, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.J.; Tan, K.M.; Harrison, C.; Ng, C.C.; Lim, W.C.; Nguyen, T.N. Diabetes, frailty and burden of comorbidities among older Malaysians with stroke. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2024, 45, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, T.T.; Davis, H.; Laskey, W.K. Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure and Diabetes Mellitus. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e003023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Morán, E.; Orueta, J.F.; Esteban, J.I.F.; Axpe, J.M.A.; González, M.L.M.; Polanco, N.T.; Loiola, P.E.; Gaztambide, S.; Nuno-Solinis, R. The prevalence of diabetes-related complications and multimorbidity in the population with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Basque Country. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.L.; Currie, C.J.; Stott, N.C.H.; Smithers, M.; Butler, C.; Peters, J.R. The prevalence of multiple diabetes-related complications. Diabet. Med. 2000, 17, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kim, S.; Choi, D.H.; Cho, E.-H. Comparison of Age of Onset and Frequency of Diabetic Complications in the Very Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 31, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, O.; Matsushita, K.; Coresh, J.; Sharrett, A.R.; McEvoy, J.W.; Windham, B.G.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Selvin, E. Mortality Implications of Prediabetes and Diabetes in Older Adults. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gual, M.; Arizá-Solé, A.; Formiga, F.; Carrillo, X.; Bañeras, J.; Tizón-Marcos, H.; Garcia-Picart, J.; Cardenas, M.; Regueiro, A.; Tomas, C.; et al. Diabetes mellitus is not independently associated with mortality in elderly patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Insights from the Codi Infart registry. Coron. Artery Dis. 2019, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regidor, E.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Seguí, M.; Serrano, R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Artola, S. Traditional Risk Factors Alone Could Not Explain the Excess Mortality in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2503–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apelqvist, J.; Agardh, C. The association between clinical risk factors and outcome of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 1992, 18, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karter, A.J.; Laiteerapong, N.; Chin, M.H.; Moffet, H.H.; Parker, M.M.; Sudore, R.L.; Adams, A.S.; Schillinger, D.; Adler, N.S.; Whitmer, R.A.; et al. Ethnic Differences in Geriatric Conditions and Diabetes Complications Among Older, Insured Adults With Diabetes. J. Aging Health 2015, 27, 894–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.S.; Liu, J.Y.; Lipska, K.J.; Grant, R.W.; Laiteerapong, N.; Moffet, H.H.; Schumm, L.P.; Karter, A.J. Data-driven classification of health status of older adults with diabetes: The diabetes and aging study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.I.; Sacre, J.W.; McDonald, S.P.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E. Excess all-cause and cause-specific mortality for people with diabetes and end-stage kidney disease. Diabet. Med. 2021, 39, e14775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, H.A.; Ghatrif, M.A.; Samper-Ternent, R.; Gerst, K.; Markides, K.S. Trends in Diabetes Prevalence and Diabetes-Related Complications in Older Mexican Americans From 1993–1994 to 2004–2005. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2212–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Weng, S.; Tsai, K.-T.; Chen, P.; Lin, H.-J.; Wang, J.-J.; Su, S.-B.; Choc, W.; Guo, H.R.; Hsu, C.H. Long-term Mortality Risk After Hyperglycemic Crisis Episodes in Geriatric Patients With Diabetes: A National Population-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.R.; Jhund, P.S.; Petrie, M.C.; Lewsey, J.; Hawkins, N.M.; Bhagra, S.; Munoz, N.; Varyani, F.; Redpath, A.; Chalmers, J.; et al. Discordant Short- and Long-Term Outcomes Associated With Diabetes in Patients With Heart Failure: Importance of Age and Sex. Circ. Heart Fail. 2008, 1, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. The relation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease to retinopathy in people with diabetes in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wei, W.B.; Xu, L.; Jonas, J.B. Prevalence, risk factors and associated ocular diseases of cerebral stroke: The population-based Beijing Eye Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e024646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingard, D.L.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; McPhillips, J.B. Prevalence of Cardiovascular and Renal Complications in Older Adults With Normal or Impaired Glucose Tolerance or NIDDM: A population-based study. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.I.; Lazzarini, P.A.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. Trends in the Incidence of Hospitalization for Major Diabetes-Related Complications in People With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Australia, 2010–2019. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, S.S.; Viggers, R.; Drewes, A.M.; Vestergaard, P.; Jensen, M.H. Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, Severe Hypoglycemia, and All-Cause Mortality in Postpancreatitis Diabetes Mellitus Versus Type 2 Diabetes: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.W.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.G. Association of advanced chronic kidney disease with diabetic retinopathy severity in older patients with diabetes: A retrospective cross-sectional study. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2022, 40, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, A.; Padrós, G.; Formiga, F.; Rojas-Farreras, S.; Perez, J.; Pujol, R. Diabetes Mellitus: Prevalence and Effect of Morbidities in the Oldest Old. The Octabaix Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, R.R.; Saudek, C.D.; Brancati, F.L.; Selvin, E. Association of Diabetes, Comorbidities, and A1C With Functional Disability in Older Adults. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cortes, J.; Mateos-Carchenilla, M.P.; Martínez-Cuevas, M.; Beca-Martínez, M.T.; Herrera-Sancho, E.; López-Rodríguez, M.C.; Jaime-Siso, M.A.; Ruiz-Lopez, M. Comorbidities and use of health services in people with diabetes mellitus according to risk levels by adjusted morbidity groups. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2024, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mark, G.; Tittel, S.R.; Sziegoleit, S.; Putz, F.J.; Durmaz, M.; Bortscheller, M.; Buschmann, I.; Seufert, J.; Holl, R.W.; Bramlage, P. Type 2 diabetes in older patients: An analysis of the DPV and DIVE databases. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 11, 2042018820958296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazlina, S.G.; Mastura, I.; Ahmad, Z.; Cheong, A.T.; Adam, B.; Haniff, J.; Lee, P.-Y.; Syed-Alwi, S.-A.-R.; Chew, B.-H.; Sriwahya, T. Control of glycemia and other cardiovascular disease risk factors in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Data from the Adult Diabetes Control and Management. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014, 14, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, K.Y.; Chan, P.F.; Lai, L.K.P.; Chow, K.L.; Chao, D.V.K. Prevalence of diabetic nephropathy among Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and different categories of their estimated glomerular filtration rate based on the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in primary care in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2019, 18, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, C.K.; Eng, C.; Cenzer, I.; Boscardin, W.J.; Rice-Trumble, K.; Lee, S.J. Glycosylated Hemoglobin and Functional Decline in Community-Dwelling Nursing Home–Eligible Elderly Adults with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.; Boaz, M.; Beloosesky, Y.; Kornowski, R.; Grossman, E. Body mass index and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hospitalized elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2009, 26, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Saldaña, J.; Morley, J.E.; Reynoso, M.T.M.; Medina, C.A.; Salazar, P.; Cruz, E.; Nayeli Torres, A.L. Diabetes Mellitus in a Subgroup of Older Mexicans: Prevalence, Association with Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Functional and Cognitive Impairment, and Mortality. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Bayer, A.; Girling, A.; Woodhouse, K.W. Older adults, diabetes mellitus and visual acuity: A community-based case-control study. Age Ageing 2000, 29, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Feng, B.; Fan, L.; Jiao, Y.; Ying, L.; Liu, H.; Hou, X.; Su, Y.; Li, D.; Fu, L. Triglyceride glucose index predicts all-cause mortality in oldest-old patients with acute coronary syndrome and diabetes mellitus. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbow, S.J.; Walsh, A.; Gill, G. Diabetes in institutionalised elderly people: A forgotten population? BMJ 1997, 314, 1868–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orces, C.H.; Lorenzo, C. Prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes among older adults in Ecuador: Analysis of the SABE survey. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2018, 12, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütt, M.; Fach, E.-M.; Seufert, J.; Kerner, W.; Lang, W.; Zeyfang, A.; Welp, R.; Holl, R.W. Multiple complications and frequent severe hypoglycaemia in ‘elderly’ and ‘old’ patients with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, e176–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| EMBASE (1974–2024) | Medline All (1946–2024) | Web of Science Core (All Fields, No Data Restriction) |

|---|---|---|

|

| (Comorbidity or “multiple chronic conditions” or “cardiovascular disease” or stroke or “isolated systolic hypertension”) AND (“Diabetes mellitus” or neuropathy or “diabetic retinopathy” or “Diabetes complications”) AND (“Aged 80 or over” or “very elderly” or “80+ years”) |

| * n = 589 | * n = 758 | * n = 426 |

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Human participants aged >80 years with a primary diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (any type) | Human participants aged <80 years Human participants categorised as ‘oldest-old’ with no details on actual age of participants Non-human subjects |

| Context | Studies reporting on diabetes-related complications and comorbidities including: CVD 1, PAD 2, Stroke, Nephropathy, Neuropathy, Retinopathy, Foot ulceration, Amputation, HTN 3, Obesity or CKD 4/ESRD 5 | Studies where diabetes is not the primary exposure Studies reporting only general comorbidity without diabetes diabetes-specific focus |

| Concept | Studies conducted in any healthcare setting or country All income settings (higher, middle, lower-income countries) | Non-English language publications Review articles, editorials, opinion pieces Studies without full-text availability |

| Types of Evidence | Original research including: Retrospective/prospective cohort studies Cross-sectional studies Case–control studies Randomised controlled trials Grey literature where full data was available | Systematic reviews Scoping reviews Meta-analysis Narrative reviews |

| Complication Comorbidity | Number of Studies (n) | Individuals ≥ 80 Years (×103) | Number Affected (×103) | Mean Prevalence (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrovascular | Cardiovascular Disease | n = 33 | 17,538 | 6577 | 37.5% |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | n = 11 | 36,369 | 38 | 10.4% | |

| Stroke | n =37 | 751 | 55 | 7.3% | |

| Microvascular | Nephropathy | n = 5 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 26.7% |

| Neuropathy | n = 9 | 200 | 42 | 20.9% | |

| Retinopathy | n = 17 | 208 | 42 | 20.1% | |

| Peripheral | Foot ulcer | n = 2 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 9.3% |

| Amputation | n = 3 | 6.0 | 0.03 | 0.5% | |

| Other Comorbidities | Hypertension | n = 28 | 16,731 | 12,465 | 74.5% |

| Obesity | n = 11 | 146 | 53 | 36.5% | |

| CKD/ESRD | n = 9 | 16,662 | 3250 | 19.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ward-Bradley, C.; Erwin, A.; Peto, T.; Cushley, L.N.; Curran, K. Complications and Comorbidities in Individuals >80 Years with Diabetes: A Scoping Review. Diabetology 2025, 6, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120152

Ward-Bradley C, Erwin A, Peto T, Cushley LN, Curran K. Complications and Comorbidities in Individuals >80 Years with Diabetes: A Scoping Review. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120152

Chicago/Turabian StyleWard-Bradley, Christian, Adam Erwin, Tunde Peto, Laura N. Cushley, and Katie Curran. 2025. "Complications and Comorbidities in Individuals >80 Years with Diabetes: A Scoping Review" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120152

APA StyleWard-Bradley, C., Erwin, A., Peto, T., Cushley, L. N., & Curran, K. (2025). Complications and Comorbidities in Individuals >80 Years with Diabetes: A Scoping Review. Diabetology, 6(12), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120152