Visual Acuity and Beyond: Sociodemographic Determinants of Quality of Life in Diabetic Retinopathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics and Transparency

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

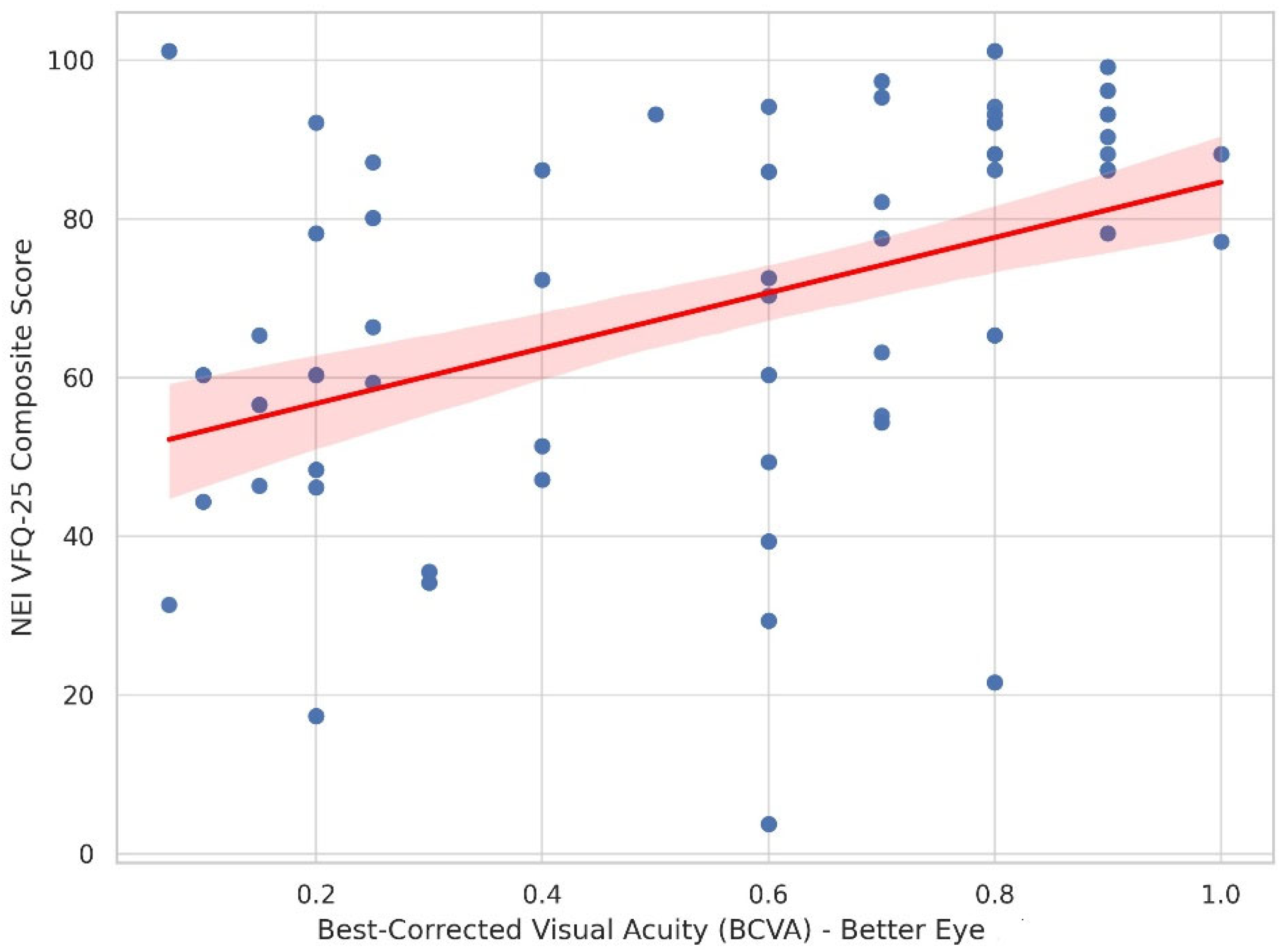

3.2. Correlation Analyses

3.3. Group Comparisons

- By DR subtype: A trend toward lower VRQoL with more advanced DR was observed (Kruskal–Wallis H(2) = 5.386, p = 0.067), corresponding to a small effect size (ε2 ≈ 0.023). Additionally, BCVA differed significantly across DR subtypes. A Kruskal–Wallis test showed a large effect (χ2(2) = 47.4, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.316). Post hoc Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner comparisons demonstrated significantly worse BCVA in PDR compared with NPDR (p < 0.001), in DME compared with NPDR (p < 0.001), and in DME compared with PDR (p = 0.009).

- By gender: An independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test showed no significant difference between males and females (U = 2740, p = 0.711), with a negligible effect size (rank-biserial r = −0.035). Median (IQR) VFQ-25 scores were 72.4 (33.8) in males and 78.2 (38.8) in females.

- By educational level: The Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a statistically significant difference across six education categories (master’s degree, bachelor’s degree, secondary, lower secondary, primary, no formal education; χ2(5) = 37.3, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.249). Multiplicity-adjusted post hoc comparisons showed higher NEI VFQ-25 composite scores in participants with university education (master’s/bachelor’s) compared with those with secondary or lower educational attainment.

- For the comparison across DR subtypes, the Kruskal–Wallis test yielded a small-to-moderate effect size (Cohen’s w = 0.19), with an estimated post hoc power of approximately 0.46 for the observed χ2 = 5.386 (df = 2, n = 151). By contrast, the effect of educational level on NEI VFQ-25 composite scores was large (w = 0.50) for χ2 = 37.3 (df = 4, n = 151), corresponding to very high observed power (>0.99).

3.4. Multivariate Regression Analysis

Model Diagnostics and Robustness

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| VRQoL | Vision-Related Quality of Life |

| NEI VFQ-25 | National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 |

| BCVA | Best-Corrected Visual Acuity |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| NPDR | Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| PDR | Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Yau, J.W.Y.; Rogers, S.L.; Kawasaki, R.; Lamoureux, E.L.; Kowalski, J.W.; Bek, T.; Chen, S.-J.; Dekker, J.M.; Fletcher, A.; Grauslund, J.; et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N.; Mitchell, P.; Wong, T.Y. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet 2010, 376, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenwick, E.K.; Xie, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Pesudovs, K.; Finger, R.P.; Wong, T.Y.; Lamoureux, E.L. The Impact of Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema on Health-Related Quality of Life in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenwick, E.K.; Pesudovs, K.; Khadka, J.; Dirani, M.; Rees, G.; Wong, T.Y.; Lamoureux, E.L. The impact of diabetic retinopathy on quality of life: Qualitative findings from an item bank development project. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Mukundan, A.; Liu, Y.S.; Tsao, Y.M.; Lin, F.C.; Fan, W.S.; Wang, H.C. Optical identification of diabetic retinopathy using hyperspectral imaging. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatarova, Z.; Hristova, E.; Bliznakova, K.; Atanasova, V.; Yaneva, Z.; Koseva, D.; Zaduryan, L.; Vasileva, G.; Stefanova, D.; Dokova, K. Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy Among Diabetic Patients from Northeastern Bulgaria. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangione, C.M.; Lee, P.P.; Gutierrez, P.R.; Spritzer, K.; Berry, S.; Hays, R.D. Development of the 25-list-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finger, R.P.; Fenwick, E.; Marella, M.; Dirani, M.; Holz, F.G.; Chiang, P.P.-C.; Lamoureux, E.L. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 3613–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemsma, R.; Boogaart, A.; Rees, A. Systematic review of the reliability and validity of the NEI VFQ-25. Health Technol. Assess. 2003, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoureux, E.L.; Tai, E.S.; Thumboo, J.; Wee, H.L.; Saw, S.M.; Wong, T.Y. Impact of diabetic retinopathy on vision-specific function. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 117, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenwick, E.K.; Rees, G.; Pesudovs, K.; Dirani, M.; Kawasaki, R.; Wong, T.Y.; Lamoureux, E.L. Social and emotional impact of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2366–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, K.W.; Bosworth, H.B.; Lee, P.P. Predicting vision-related quality of life in patients with glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.M.; Brown, G.C.; Sharma, S. Utility values and diabetic retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 128, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nispen, R.M.; de Boer, M.R.; Hoeijmakers, J.G.; Ringens, P.J.; van Rens, G.H. Co-morbidity and visual acuity are risk factors for health-related quality of life decline: Five-month follow-up EQ-5D data of visually impaired older patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujosevic, S.; Midena, E. Retinopathy in diabetes. In Textbook of Diabetes, 5th ed.; Holt, R.I.G., Cockram, C.S., Flyvbjerg, A., Goldstein, B.J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 723–738. [Google Scholar]

- Lamoureux, E.L.; Hassell, J.B.; Keeffe, J.E. The impact of diabetic retinopathy on participation in daily living. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004, 122, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, D.B.P.; Yang, K.C.H.O.; Whitaker, D. Visual acuity changes throughout adulthood in normal, healthy eyes: Seeing beyond 6/6. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1995, 72, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Predictor | B (Unstandardized) | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better eye (BCVA) | 35.38 | 25.81 | 44.95 | <0.001 |

| Education Level | −10.15 | −13.92 | −6.38 | <0.001 |

| DR Subtype | 6.63 | 1.91 | 11.36 | 0.007 |

| Age | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.31 | 0.212 |

| Sex (Male) | −2.11 | −6.78 | 2.56 | 0.381 |

| HbA1c (Categorical) | −1.24 | −4.12 | 1.64 | 0.398 |

| Duration of Diabetes | −0.04 | −0.36 | 0.28 | 0.821 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hristova, E.; Zaduryan, L.; Vasileva, G.; Petkova, I.; Radeva, M.; Zlatarova, Z. Visual Acuity and Beyond: Sociodemographic Determinants of Quality of Life in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetology 2025, 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120153

Hristova E, Zaduryan L, Vasileva G, Petkova I, Radeva M, Zlatarova Z. Visual Acuity and Beyond: Sociodemographic Determinants of Quality of Life in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120153

Chicago/Turabian StyleHristova, Elitsa, Lidiya Zaduryan, Gabriela Vasileva, Iliyana Petkova, Mladena Radeva, and Zornitsa Zlatarova. 2025. "Visual Acuity and Beyond: Sociodemographic Determinants of Quality of Life in Diabetic Retinopathy" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120153

APA StyleHristova, E., Zaduryan, L., Vasileva, G., Petkova, I., Radeva, M., & Zlatarova, Z. (2025). Visual Acuity and Beyond: Sociodemographic Determinants of Quality of Life in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetology, 6(12), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120153