Perinatal Outcomes of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy: A 10-Year Single-Centre Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Maternal Characteristics

3.2. Neonatal Characteristics

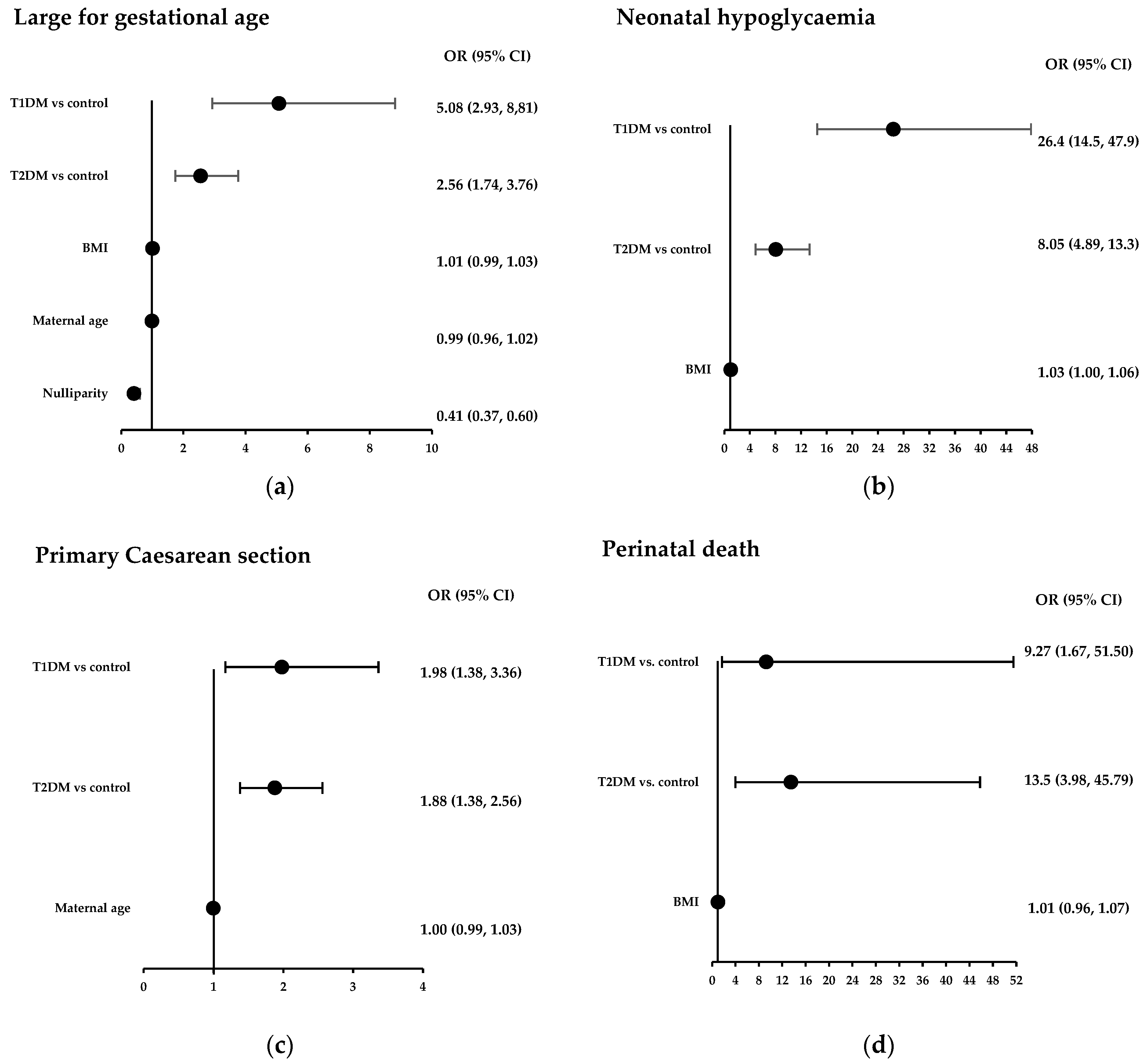

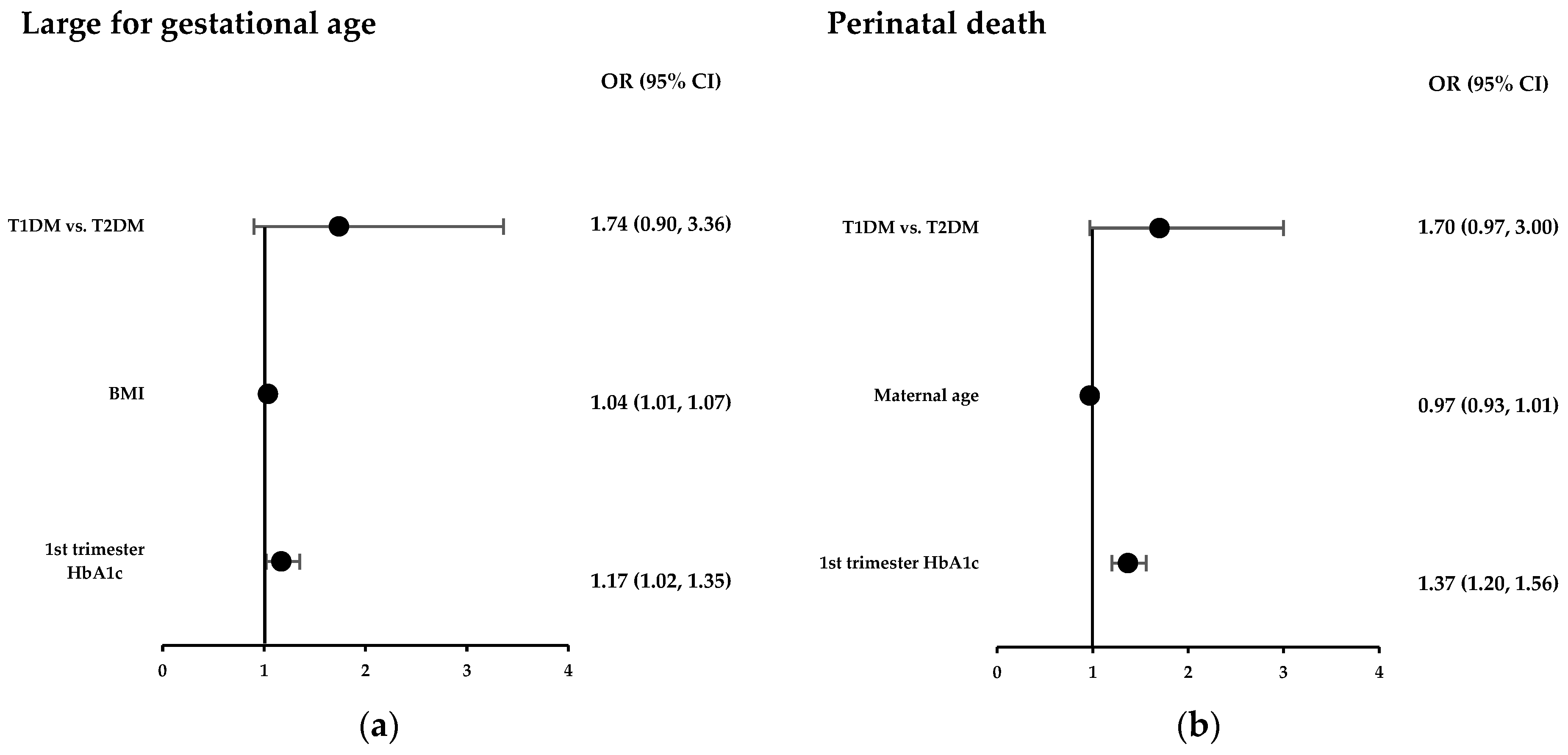

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T1DM | Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| LGA | Large for gestational age |

| CS | Caesarean section |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| BOS | Birthing Outcomes System |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Indicators for the Australian National Diabetes Strategy 2016–2020: Data Update; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, K.J.; Schuller, K.L. The increasing prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 34, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feig, D.S.; Hwee, J.; Shah, B.R.; Booth, G.L.; Bierman, A.S.; Lipscombe, L.L. Trends in incidence of diabetes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: A large, population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 1996–2010. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.; Bailey, K.; Cresswell, T.; Hawthorne, G.; Critchley, J.; Lewis-Barned, N. Trends in prevalence and outcomes of pregnancy in women with pre-existing type I and type II diabetes. BJOG 2008, 115, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzeid, M.; Versace, V.L.; Janus, E.D.; Davey, M.A.; Philpot, B.; Oats, J.; Dunbar, J.A. A population-based observational study of diabetes during pregnancy in Victoria, Australia, 1999–2008. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheme, N.D.S. Diabetes Australia: Diabetes Map. 2021. Available online: https://map.ndss.com.au (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Wändell, P.E.; Carlsson, A.C. Time trends and gender differences in incidence and prevalence of type 1 diabetes in Sweden. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2013, 9, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, J.; Yates, C.J.; Hamblin, P.S.; Kevat, D.; Shahid, I.; Teale, G.; Lee, I. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal obesity and associated perinatal outcomes over 10 years in an Australian tertiary maternity provider. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 203, 110793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, E.A.; Williamson, R.; Shub, A. Pregnancy outcomes for women with pre-pregnancy diabetes mellitus in Australian populations, rural and metropolitan: A review. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElduff, A.; Ross, G.P.; Lagström, J.A.; Champion, B.; Flack, J.R.; Lau, S.M.; Moses, R.G.; Seneratne, S.; McLean, M.; Cheung, N.W. Pregestational diabetes and pregnancy: An Australian experience. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, S.K.; Boyle, J.A.; de Courten, B.; Knight, M.; Ranasinha, S.; Regan, J.; Soldatos, G.; Wallace, E.M.; Zoungas, S.; Teede, H.J. Contemporary type 1 diabetes pregnancy outcomes: Impact of obesity and glycaemic control. Med. J. Aust. 2016, 205, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, S.K.; Boyle, J.A.; de Courten, B.; Soldatos, G.; Wallace, E.M.; Zoungas, S.; Teede, H.J. Impact of type 2 diabetes, obesity and glycaemic control on pregnancy outcomes. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 57, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, M.; García-Patterson, A.; Gich, I.; Corcoy, R. Maternal and fetal outcome in women with type 2 versus type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4284–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, H.R.; Howgate, C.; O’Keefe, J.; Myers, J.; Morgan, M.; Coleman, M.A.; Jolly, M.; Valabhji, J.; Scott, E.M.; Knighton, P.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A 5-year national population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zeng, X.L.; Cheng, M.L.; Yang, G.Z.; Wang, B.; Xiao, Z.W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, B.F.; Xiao, D.W.; Zhang, S.; et al. Quantitative assessment of the effect of pre-gestational diabetes and risk of adverse maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcomes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 61048–61056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer Care Victoria. Maternity Dashboard User Handbook; Safer Care Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, H.R.; Bell, R.; Cartwright, C.; Curnow, P.; Maresh, M.; Morgan, M.; Sylvester, C.; Young, B.; Lewis-Barned, N. Improved pregnancy outcomes in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes but substantial clinic-to-clinic variations: A prospective nationwide study. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, D.S.; Davern, R.; Rutter, E.; Coveney, C.; Devine, H.; Walsh, J.M.; Higgins, M.; Hatunic, M. Pre-Gestational Diabetes and Pregnancy Outcomes. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 2873–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, H.R.; Steel, S.A.; Roland, J.M.; Morris, D.; Ball, V.; Campbell, P.J.; Temple, R.C. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes: Influences of glycaemic control, obesity and social disadvantage. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin No. 201: Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, e228–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, N.; Herranz, L.; Vaquero, P.M.; Villarroel, A.; Fernandez, A.; Pallardo, L.F. Is Pregnancy Outcome Worse in Type 2 Than in Type 1 Diabetic Women? Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2557–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seah, J.-m.; Kam, N.M.; Wong, L.; Tanner, C.; Shub, A.; Houlihan, C.; Ekinci, E.I. Risk factors for pregnancy outcomes in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, M.; Ternynck, C.; Bourry, J.; Baudoux, F.; Subtil, D.; Vambergue, A. Association Between HbA1c Levels on Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes During Pregnancy in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e1117–e1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.D.; Mathiesen, E.; Ekbom, P.; Hellmuth, E.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T.; Damm, P. Poor Pregnancy Outcome in Women With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Mothers and Babies. 2025. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Cundy, T.; Morgan, J.; O’Beirne, C.; Gamble, G.; Budden, A.; Ivanova, V.; Wallace, M. Obstetric interventions for women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 123, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abalos, E.; Cuesta, C.; Grosso, A.L.; Chou, D.; Say, L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.; Lemoine, E.; Granger, J.P.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1094–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, M.C.; Fleming, K.M.; Bailey, J.A.; Doyle, P.; Modder, J.; Acolet, D.; Golightly, S.; Miller, A. Perinatal mortality and congenital anomalies in babies of women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland: Population based study. BMJ 2006, 333, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Controls | T2DM | T1DM | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | n = 1641 | n = 317 | n = 92 | |

| 29.5 (6.5) | 33.4 (5.1) | 29.7 (5.8) | * <0.001 † 0.95 ‡ <0.001 | |

| Country of birth (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 661 (40.3) | 149 (47) | 71 (77.2) | <0.001 |

| Southeast Asia | 342 (20.8) | 50 (15.8) | 11 (11.9) | |

| South Asia | 293 (17.8) | 34 (10.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Africa | 106 (6.5) | 26 (8.2) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Pacific Islands | 82 (5.0) | 43 (13.6) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Others | 157 (9.6) | 13 (4.1) | 2 (2.1) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | n = 1319 | n = 269 | n = 72 | |

| 25.3 (22.0, 31.0) | 34.5 (29.6, 40.4) | 26.8 (22.9, 31.6) | * <0.001 † 0.17 ‡ <0.001 | |

| Parity (%) | ||||

| 0 | 650 (39.6) | 78 (24.6) | 41 (44.6) | * <0.001 |

| >1 | 991 (60.4) | 239 (75.4) | 51 (55.4) | † 0.35 |

| ‡ <0.001 | ||||

| Duration of diabetes (years) | - | n = 303 | n = 87 | |

| 3.2 (3.5) | 11.7 (7.9) | ‡ <0.001 | ||

| HbA1c (First in pregnancy) mmol/L % | - | n = 304 | n = 86 | |

| 49 (41, 61) 6.6 (5.9, 7.7) | 61 (50, 78) 7.75 (6.7, 9.3) | ‡ <0.001 | ||

| HbA1C (3rd trimester) mmol/L % | - | n = 295 | n = 89 | |

| 41 (36, 51) 5.9 (5.4, 6.8) | 52 (44, 62) 6.9 (6.2, 7.8) | ‡ <0.001 | ||

| Mode of Delivery (%) | n = 1618 | n = 317 | n = 92 | |

| Vaginal delivery | 918 (56.7) | 105 (33.1) | 19 (20.7) | * <0.001 |

| Forceps/Vacuum | 190 (11.7) | 15 (10.8) | 9 (9.8) | † <0.001 |

| Elective caesarean section | 241 (14.9) | 107 (33.8) | 37 (40.2) | ‡ 0.05 |

| Emergency caesarean section | 269 (16.6) | 90 (28.3) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Primary caesarean section (%) | 234 (17.2) | 78 (28.9) | 21 (29.2) | * <0.001 † 0.009 ‡ 0.94 |

| Gestational hypertension (%) | 37 (2.3) | 30 (9.5) | 8 (8.7) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.35 |

| Pre-eclampsia (%) | 24 (1.5) | 15 (4.7) | 6 (6.5) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.49 |

| Characteristic | Controls | T2DM | T1DM | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | n = 1641 | n = 317 | n = 92 | |

| 811 (49.4%) | 166 (52.4%) | 41 (44.6%) | 0.99 | |

| Gestation at birth (weeks) | 39.2 (38.4, 40) | 37.6 (37.0, 38.2) | 37.0 (36.1, 37.6) | * <0.001 † < 0.001 ‡ <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3302.5 (560) | 3291 (873) | 3390 (747) | * 0.42 † 0.02 ‡ 0.207 |

| Birth weight z-score | −0.1 (−0.8, 0.5) | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.29, 1.9) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.007 |

| Large for gestational age (%) | 137 (8.4%) | 77 (24.3%) | 33 (35.9%) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.03 |

| SCN admission (%) | 58 (3.5%) | 37 (11.7%) | 18 (19.6%) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.05 |

| Neonatal hypoglycaemia (%) | 40 (2.4%) | 66 (20.8%) | 35 (38.0) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.003 |

| Jaundice with phototherapy (%) | 83 (5.1%) | 39 (12.3%) | 23 (25.0%) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.15 |

| Respiratory morbidity (%) | 74 (4.5%) | 37 (11.7%) | 16 (17.4%) | * <0.001 † <0.001 ‡ 0.001 |

| Birth trauma (%) | 360 (21.9%) | 70 (22.1%) | 23 (25.0%) | * 0.95 † 0.49 ‡ 0.56 |

| Shoulder dystocia (%) | 28 (1.7%) | 9 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | * 0.18 † 0.21 ‡ 0.10 |

| Congenital anomaly (%) | 73 (4.5%) | 35 (11.0%) | 10 (10.9%) | * <0.001 † 0.005 ‡ 0.96 |

| Perinatal death (%) | 8 (0.5%) | 13 (4.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | * <0.001 † 0.04 ‡ 0.39 |

| Stillbirth (%) | 3 (0.2%) | 9 (2.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | * <0.001 † 0.002 ‡ 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lawton, P.; Lu, J.; Endall, R.; Luo, J.; Foskey, R.; Kevat, D.; Hamblin, P.S.; Said, J.M.; Teale, G.; Yates, C.J.; et al. Perinatal Outcomes of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy: A 10-Year Single-Centre Cohort Study. Diabetology 2025, 6, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120151

Lawton P, Lu J, Endall R, Luo J, Foskey R, Kevat D, Hamblin PS, Said JM, Teale G, Yates CJ, et al. Perinatal Outcomes of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy: A 10-Year Single-Centre Cohort Study. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120151

Chicago/Turabian StyleLawton, Paul, Jean Lu, Ryan Endall, Jing Luo, Rebecca Foskey, Dev Kevat, Peter S. Hamblin, Joanne M. Said, Glyn Teale, Christopher J. Yates, and et al. 2025. "Perinatal Outcomes of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy: A 10-Year Single-Centre Cohort Study" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120151

APA StyleLawton, P., Lu, J., Endall, R., Luo, J., Foskey, R., Kevat, D., Hamblin, P. S., Said, J. M., Teale, G., Yates, C. J., & Lee, I.-L. (2025). Perinatal Outcomes of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy: A 10-Year Single-Centre Cohort Study. Diabetology, 6(12), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120151