Animal Skin Attenuation in the Millimeter Wave Spectrum

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the dependence of S21 (transmission) and S11 (reflection) on “skin + fat” thickness?

- What is the variation in the dependence of S21 and S11 on “skin + fat” thickness, given that real samples are not uniformly thick with respect to neither the components of skin nor of fat?

- What is the dependence of S21 and S11 on polarization, given the direction of hair with respect to the said polarization?

- What is the dependence of S21 and S11 on frequencies in the 75–110 GHz spectral range?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Experimental Plan

2.2. Preliminary Preparations

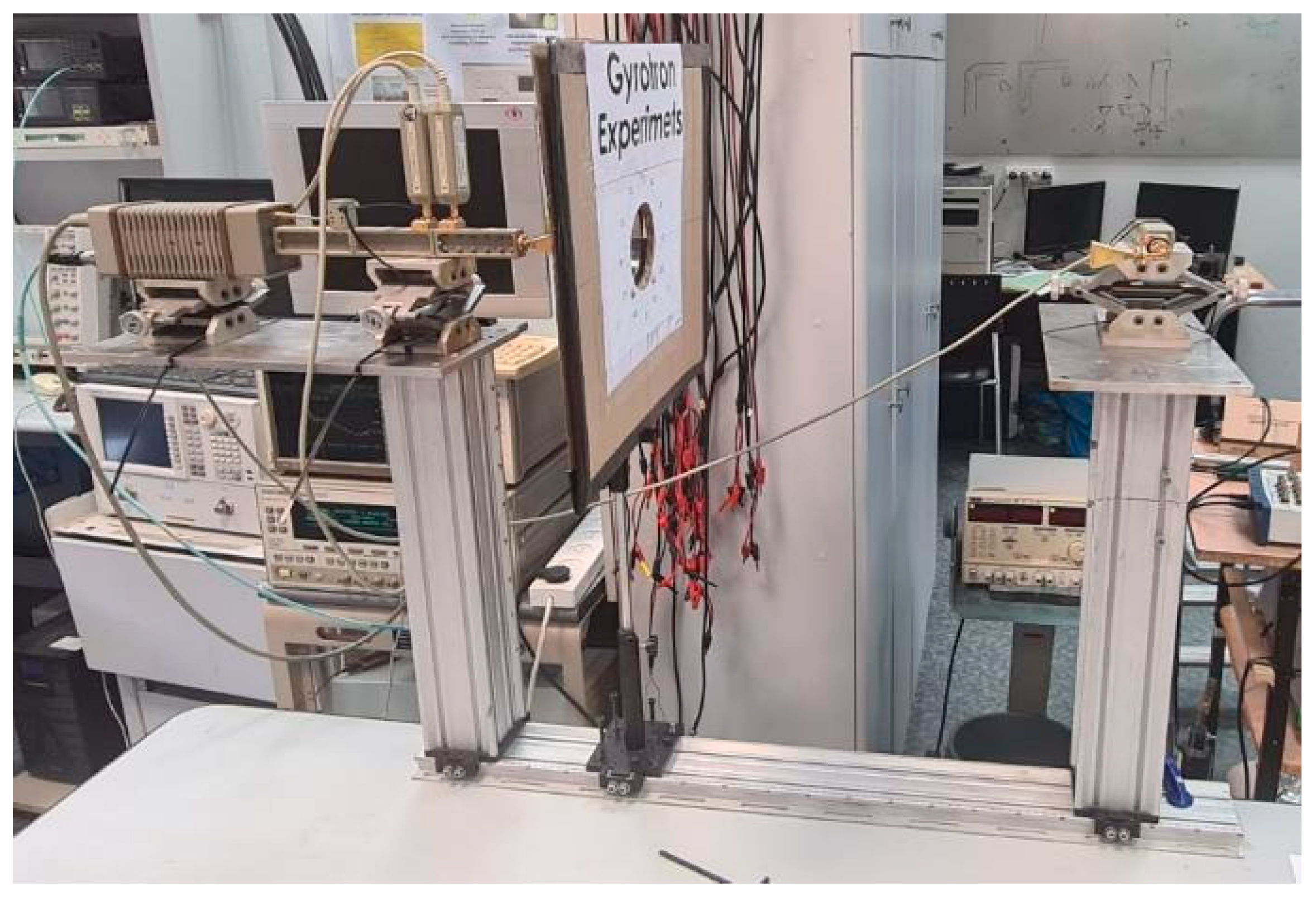

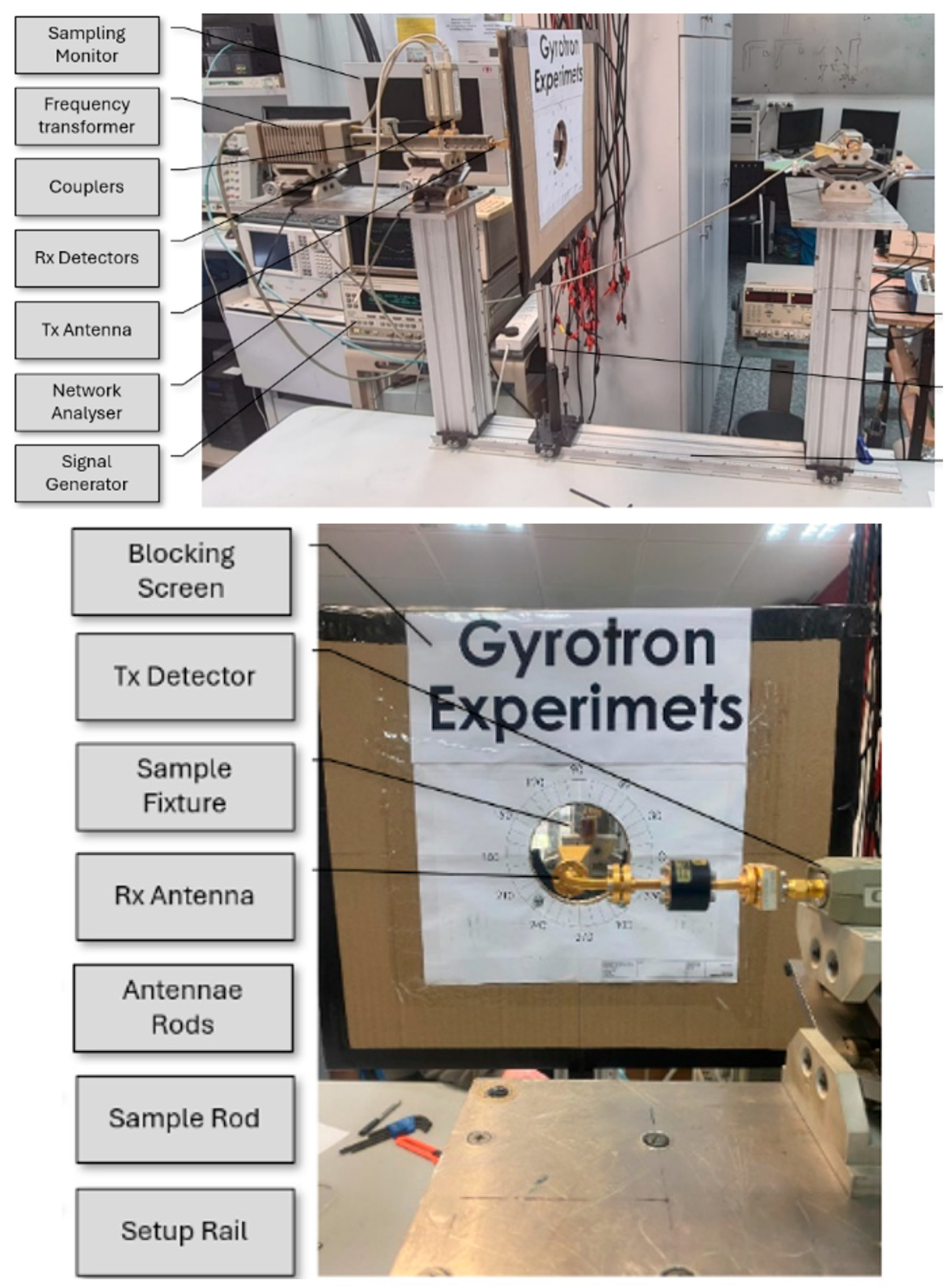

2.3. Array for Near-Field Measurements

2.4. Design of the Array for Far-Field Measurements

2.5. Main Points of the Experiment

2.6. Sensitivity Calculations

- Given the experimental geometry (Tx at 350 mm from the sample and Rx at 700 mm from the Tx antenna), the sample is illuminated by a beam in the Radiative Near-Field [21] (Fresnel) for the entire spectral band. The Rx antenna is placed at the Far-Field Boundary.

- Beam on the sample: At the sample plane ( mm), the calculated mode field radius () is approximately 32 mm slightly more than the size of the antenna aperture. The horn illuminates a spot of ~64 mm diameter (at 1/e2) on the sample. The half-power spot (−3 dB) is ~59% of the spot size, which is 37 mm [23]. The rest of the 85 mm diameter Petri dish does not contribute to the measurement.

- The receiving antenna was positioned in the far-field at mm to ensure phase planarity. At the receiver plane, the transmitted beam radius expands to mm. It acts as a spatial filter, coupling only the central mm core of the beam that passed through the sample center. This rejects edge scattering and peripheral thickness variations, ensuring S21 is due to bulk central tissue properties. Consequently, the “field non-uniformity” effectively acts as a constant weighting function of a Fundamental Gaussian pattern rather than a source of random error.

- Prior to the S-parameters measurements, the setup was calibrated according to the actual distances and the alignment of the antennas to ensure the relative measurement of power attenuation and reflection S-parameters as described in Section 2.7. Conservatively, assuming ±1 mm sample positioning tolerance, lateral misalignment loss [23,25]:

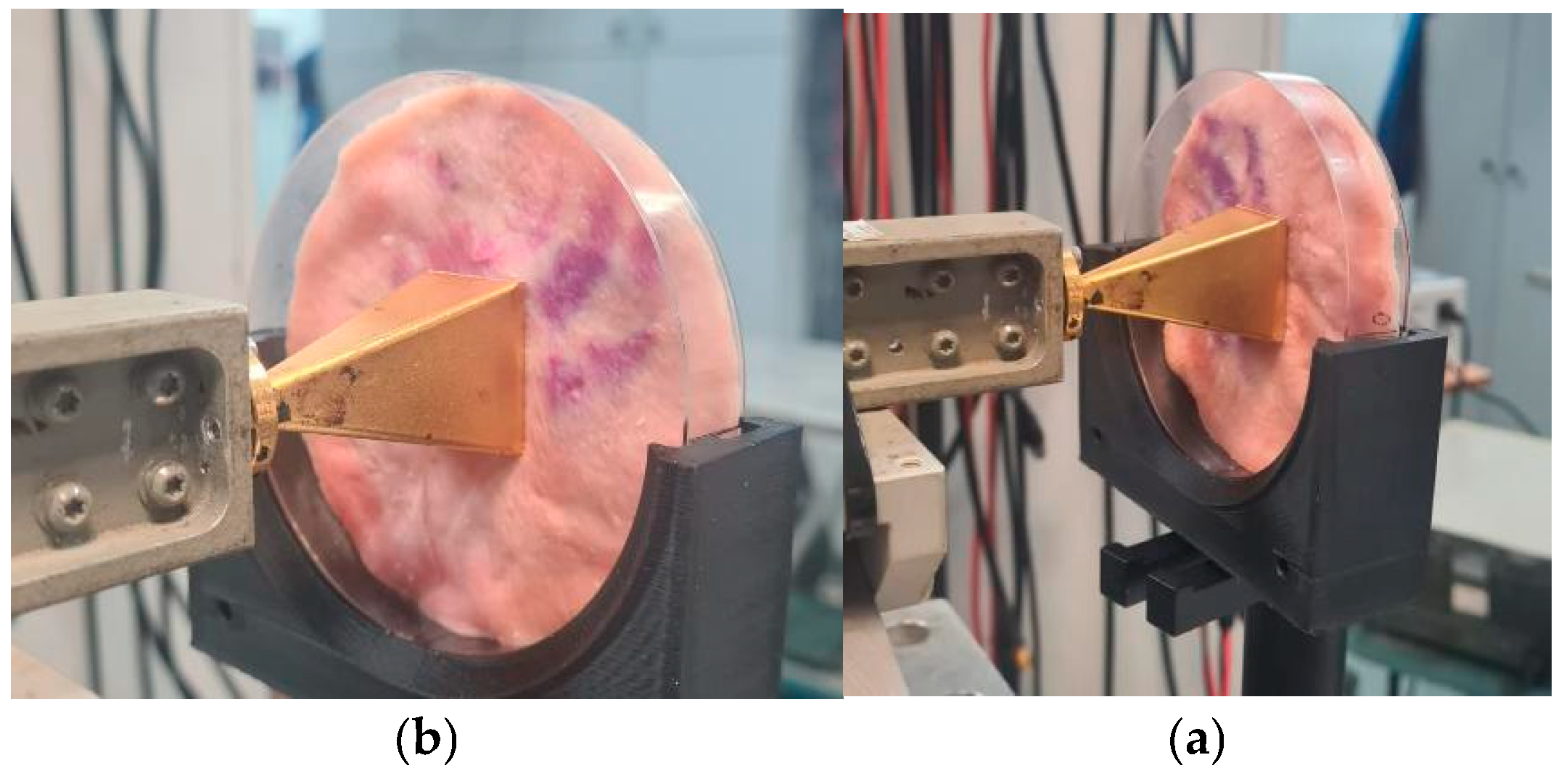

2.7. Preparation of the Samples

2.8. Performing Measurements

- 0-degree central position.

- 90-degree central position (by rotating the Petri dish around the zero point).

- Two laterally displaced positions by two-thirds of the diameter as depicted in Figure 14.

- 0-degree central position.

- 90-degree central position (by rotating the Petri dish around the zero point).

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Results and Initial Data Analysis

3.2. Raw S21 Measurements

3.3. Raw S11 Measurements

3.4. Attenuation Segmentation by Sample Thickness at the Measurement Frequency

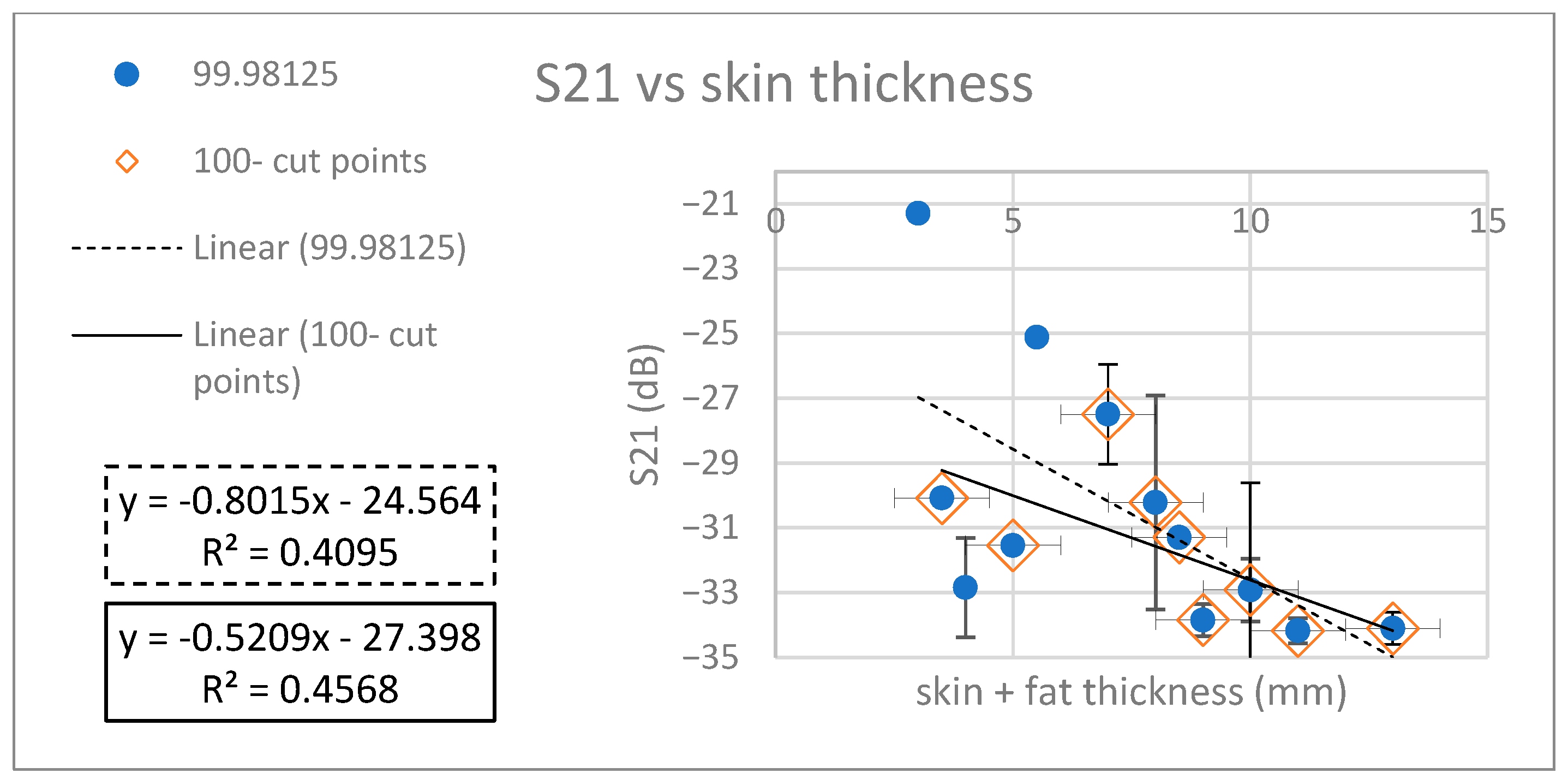

3.5. Absorption as Function of Sample Thickness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Recommendations for Further Action

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.; Ward, E.; Hao, Y.; Xu, J.; Thun, M.J. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2009, 59, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.; Xu, J.; Ward, E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wao, H.; Mhaskar, R.; Kumar, A.; Miladinovic, B.; Djulbegovic, B. Survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer without treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, N.; Idehara, T.; Khutoryan, E.; Fukunaga, Y.; Bibin, A.B.; Ito, S.; Sabchevski, S.P. Combined Hyperthermia and Photodynamic Therapy Using a Sub-THz Gyrotron as a Radiation Source. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2016, 37, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, W.R. Tissue Interactions with Nonionizing Electromagnetic Fields. Physiol. Rev. 1981, 61, 435–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, F.; Liberti, M.; Paffi, A.; Merla, C.; Marracino, P.; Denzi, A.; Marino, C.; D’Inzeo, G. Feasibility for Microwaves Energy to Affect Biological Systems Via Nonthermal Mechanisms: A Systematic Approach. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2013, 61, 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Akyel, Y.; Pakhomova, O.N.; Stuck, B.E.; Murphy, M.R. Current state and implications of research on biological effects of millimeter waves: A review of the literature. Bioelectromagnetics 1998, 19, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffi, A.; Apollonio, F.; Lovisolo, G.A.; Marino, C.; Pinto, R.; Repacholi, M.; Liberti, M. Considerations for Developing an RF Exposure System: A Review for in vitro Biological Experiments. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2010, 58, 2702–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, H. Long-range coherence and energy storage in biological systems. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1968, 2, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojavin, M.A.; Ziskin, M.C. Medical application of millimetre waves. Int. J. Med. 1998, 91, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, X. Advances in Millimeter-Wave Treatment and Its Biological Effects Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logani, M.K.; Szabo, I.; Makar, V.; Bhanushali, A.; Alekseev, S.; Ziskin, M.C. Effect of millimeter wave irradiation on tumor metastasis. Bioelectromagnetics 2006, 27, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Luo, T.; Zhong, G.Y.; Liu, A.; Zeng, Q.; Xin, S.X. Apoptosis-Promoting Effects on A375 Human Melanoma Cells Induced by Exposure to 35.2-GHz Millimeter Wave. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 19, 1533033820934131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Komoshvili, K.; Levitan, J.; Aronov, S.; Kapilevich, B.; Yahalom, A. Millimeter Waves Non-Thermal Effect on Human Lung Cancer Cells. In Proceedings of the 3rd International IEEE Conference on Microwaves, Communications, Antennas and Electronic Systems (COMCAS 2011), Tel Aviv, Israel, 7–9 November 2011; p. 1D2-2. [Google Scholar]

- Komoshvili, K.; Becker, T.; Levitan, J.; Yahalom, A.; Barbora, A.; Liberman-Aronov, S. Morphological Changes in H1299 Human Lung Cancer Cells Following W-Band Millimeter-Wave Irradiation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, O.; Komoshvili, K.; Levitan, J.; Yahalom, A.; Marks, H.; Borodin, D.; Liberman-Aronov, S. The Lack of Toxic Effect of High-Power Short-Pulse 101 GHz Millimeter Waves on Healthy Mice. Bioelectromagnetics 2020, 41, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoshvili, K.; Israel, K.; Levitan, J.; Yahalom, A.; Barbora, A.; Liberman-Aronov, S. W-Band Millimeter Waves Targeted Mortality of H1299 Human Lung Cancer Cells without Affecting Non-Tumorigenic MCF-10A Human Epithelial Cells In Vitro. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbora, A.; Rajput, S.; Komoshvili, K.; Levitan, J.; Yahalom, A.; Liberman-Aronov, S. Non-Ionizing Millimeter Waves Non-Thermal Radiation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—Insights and Interactions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruszowiec, M.; Czarczyński, W.; Pliński, E.F.; Więckowski, T. Gyrotron Technology. J. Telecommun. Inf. Technol. 2014, 1, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, S.R.; Aragón-Zavala, A.A. Antennas and Propagation for Wireless Communication Systems, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2024; 752p, ISBN 978-1-119-33219-0. [Google Scholar]

- Capozzoli, A.; Curcio, C.; D’agostino, F.; Liseno, A. A Review of the Antenna Field Regions. Electronics 2024, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, V.F. Foundations of Antenna Theory and Techniques; Pearson India: Pallavaram Chennai, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, P.F. Chap. 2: Gaussian Beam Propagation. In Quasioptical Systems: Gaussian Beam Quasioptical Propagation and Applications; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.A.; McCabe, M.; Withington, S. Murphy, Gaussian beam mode analysis of the coupling of power between horn antennas. Int. J. Infrared Millim. Waves 1997, 18, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, P.F. Chap. 4: Gaussian Beam Coupling, eq. 4.25, 4.30, 4.32. In Quasioptical Systems: Gaussian Beam Quasioptical Propagation and Applications; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aronov, S.; Einat, M.; Furman, O.; Pilossof, M.; Komoshvili, K.; Ben-Moshe, R.; Yahalom, A.; Levitan, J. Millimeter-wave insertion loss of mice skin. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2017, 32, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.H.; Wu, D.L. Ice and Water Permittivities for Millimeter and Sub-millimeter Remote Sensing Applications. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2004, 5, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einat, M.; Pilossof, M.; Ben-Moshe, R.; Hirshbein, H.; Borodin, D. 95 GHz gyrotron with ferroelectric cathode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 185101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilossof, M.; Einat, M. A 95 GHz mid-power gyrotron for medical applications measurements. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 86, 016113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilossof, M.; Einat, M. 95-GHz Gyrotron With Room Temperature Dc Solenoid. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2018, 65, 3474–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, L.S.; Marsay, K.S.; Shevchenko, S.; Pilossof, M.; Levi, N.; Einat, M.; Oren, M.; Gerlitz, G. Corona and polio viruses are sensitive to short pulses of W-band gyrotron radiation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3967–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteinman, A.; Anker, Y.; Einat, M. Hard Rock Absorption Measurements in the W-Band. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2024, 45, 808–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A.; Faingersh, A.; Eliran, A.; Volshonok, M.; Kleinman, H.; Wolowelsky, S.; Yakover, Y.; Kapilevich, B.; Lasser, Y.; Seidov, Z.; et al. Radiation measurements in the new tandem accelerator FEL. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2004, 528, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socol, Y.; Gover, A.; Eliran, A.; Volshonok, M.; Pinhasi, Y.; Kapilevich, B.; Yahalom, A.; Lurie, Y.; Kanter, M.; Einat, M.; et al. Coherence limits and chirp control in long pulse free electron laser oscillator. Phys. Rev. Spéc. Top.—Accel. Beams 2005, 8, 080701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Qi, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Kong, L.; Chen, J. Real-Time Global Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Connected PHEVs Based on Traffic Flow Information. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 20032–20042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Lan, P.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, F.; Hong, J. Multi-U-Style micro-channel in liquid cooling plate for thermal management of power batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 256, 123984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency (GHz) | Wavelength (mm) | Far-Field Limit (mm) | Reactive Near-Field Limit (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 4 | 477.6 | 53.27 |

| 95 | 3.158 | 605 | 59.95 |

| 110 | 2.727 | 700 | 64.51 |

| Frequency (GHz) | BW (Degrees) | Far-Field Limit (mm) | Spot Size (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 10.35 | 477.6 | 86.54 |

| 95 | 8.17 | 605 | 86.46 |

| 110 | 7.06 | 700 | 86.35 |

| Sort by Skin Width | Average | Average | Average | Average | Average | Average | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_00_L | M_00_R | ||||||||||||

| S_00_C | C_00_L | M_00_C | M_00_L | O_00_L | O_00_C | ||||||||

| D_00_L | D_00_C | S_00_R | A_00_C | A_00_R | A_00_L | B_00_R | B_00_C | C_00_R | B_00_L | C_00_C | O_00_R | ||

| Skin Width [mm] | 1 | 2 | 2.125 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.75 | 2.5 | 3.25 | |

| Fat Width [mm] | 2 | 1.5 | 1.875 | 3 | 3 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.25 | 8.5 | 9.75 | |

| Skin + Fat Width [mm] | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 | 5.5 | 7 | 8 | 8.5 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | |

| Name Reference | D | D | S | A | A | A | B+C | B | M+C | M+B | O+C | O | |

| avg | 79.9875 | −22.175 | −28.276 | −31.065 | −22.529 | −24.342 | −27.153 | −30.081 | −22.659 | −32.276 | −29.042 | −31.096 | −31.797 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.009 | 0.097 | 1.979 | 0.031 | 0.122 | 0.050 | 1.522 | 0.017 | 0.210 | 1.001 | 0.995 | 0.107 | |

| avg | 85.01875 | −22.395 | −26.385 | −31.659 | −22.571 | −23.041 | −27.075 | −28.847 | −24.292 | −32.659 | −28.960 | −32.046 | −32.546 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.045 | 0.126 | 1.328 | 0.042 | 0.027 | 0.117 | 2.679 | 0.165 | 0.333 | 0.677 | 0.218 | 0.050 | |

| avg | 90.00625 | −23.211 | −25.526 | −31.934 | −24.102 | −24.268 | −25.055 | −28.277 | −28.647 | −32.468 | −28.834 | −32.385 | −33.034 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.041 | 0.028 | 1.080 | 0.151 | 0.064 | 0.119 | 2.724 | 0.318 | 0.464 | 0.019 | 0.478 | 0.035 | |

| avg | 94.99375 | −23.188 | −27.158 | −32.488 | −28.011 | −25.248 | −25.117 | −29.578 | −32.487 | −33.111 | −30.514 | −33.929 | −33.823 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.075 | 0.130 | 1.895 | 0.310 | 0.035 | 0.093 | 2.803 | 0.063 | 0.713 | 0.541 | 0.013 | 0.047 | |

| avg | 99.98125 | −21.293 | −30.078 | −32.844 | −31.538 | −25.109 | −27.491 | −30.214 | −31.294 | −33.844 | −32.917 | −34.172 | −34.102 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.155 | 0.130 | 1.537 | 0.143 | 0.073 | 0.165 | 3.305 | 0.187 | 0.497 | 0.975 | 0.390 | 0.149 | |

| avg | 105.0125 | −18.364 | −30.402 | −31.656 | −31.785 | −23.726 | −28.647 | −28.263 | −28.989 | −32.090 | −31.246 | −31.934 | −32.375 |

| Sta.Dev | 0.179 | 0.178 | 0.767 | 0.054 | 0.093 | 0.039 | 3.127 | 0.164 | 0.147 | 0.297 | 0.117 | 0.033 |

| Freq [GHz] | Slope [dB/GHz] | Relative Update [%] | Constant Term [dB] | Relative Update [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Points Data Set | 9 Points Data Set | 12 Points Data Set | 9 Points Data Set | |||

| 80 | −0.65 | −0.81 | 24.92 | −23.00 | −22.20 | 3.48 |

| 85 | −1.01 | −0.79 | 21.74 | −19.70 | −21.95 | 11.42 |

| 90 | −0.81 | −0.98 | 21.47 | −22.26 | −20.34 | 8.63 |

| 95 | −0.82 | −1.01 | 23.26 | −23.49 | −21.94 | 6.60 |

| 100 | −0.80 | −0.52 | 35.01 | −24.56 | −27.40 | 11.56 |

| 105 | −0.68 | −0.58 | 15.27 | −24.14 | −24.88 | 3.07 |

| average | 23.61 | 7.46 | ||||

| STD | 4.24 | 3.08 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shay, Y.; Shteinman, A.; Einat, M.; Yahalom, A.; Tuchinsky, H.; Liberman-Aronov, S. Animal Skin Attenuation in the Millimeter Wave Spectrum. Eng 2026, 7, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7020067

Shay Y, Shteinman A, Einat M, Yahalom A, Tuchinsky H, Liberman-Aronov S. Animal Skin Attenuation in the Millimeter Wave Spectrum. Eng. 2026; 7(2):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7020067

Chicago/Turabian StyleShay, Yarden, Alex Shteinman, Moshe Einat, Asher Yahalom, Helena Tuchinsky, and Stella Liberman-Aronov. 2026. "Animal Skin Attenuation in the Millimeter Wave Spectrum" Eng 7, no. 2: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7020067

APA StyleShay, Y., Shteinman, A., Einat, M., Yahalom, A., Tuchinsky, H., & Liberman-Aronov, S. (2026). Animal Skin Attenuation in the Millimeter Wave Spectrum. Eng, 7(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7020067