Underground Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: A Simulation Case Study in the Midwest United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Geological Model

2.3. Reservoir Simulation

2.3.1. Grid Size Refinement and Selection

2.3.2. Hysteresis, Solubility, and Diffusivity Parameters

- ‣

- Sgrh is the residual gas saturation after hysteresis;

- ‣

- Sgh is the current gas saturation;

- ‣

- Sgic is the gas saturation at the start of the imbibition cycle;

- ‣

- C is a land specific trapping constant;

- ‣

- (Sgr)max is the maximum residual gas saturation.

2.3.3. Simulation Setup

3. Results and Discussion

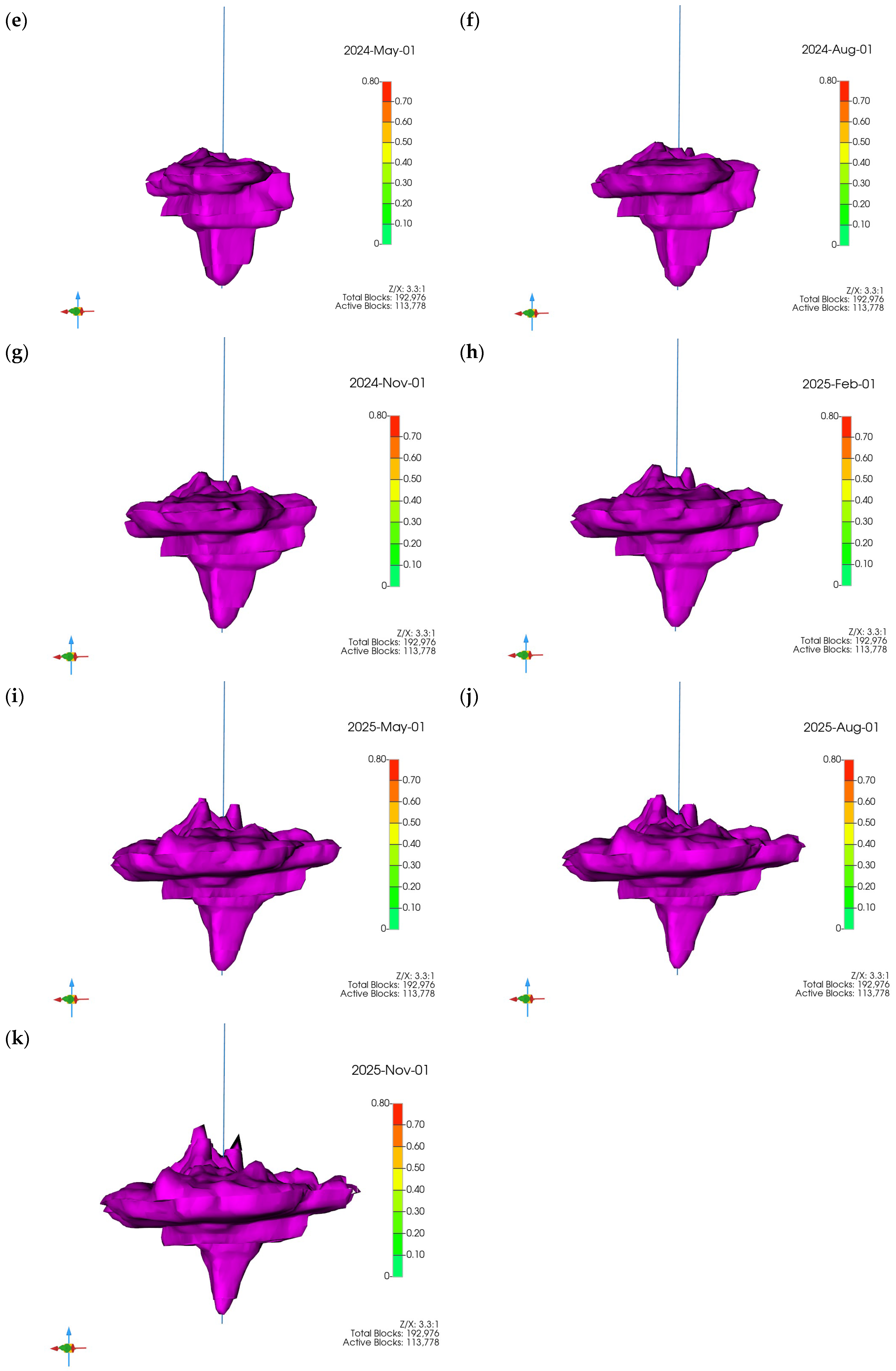

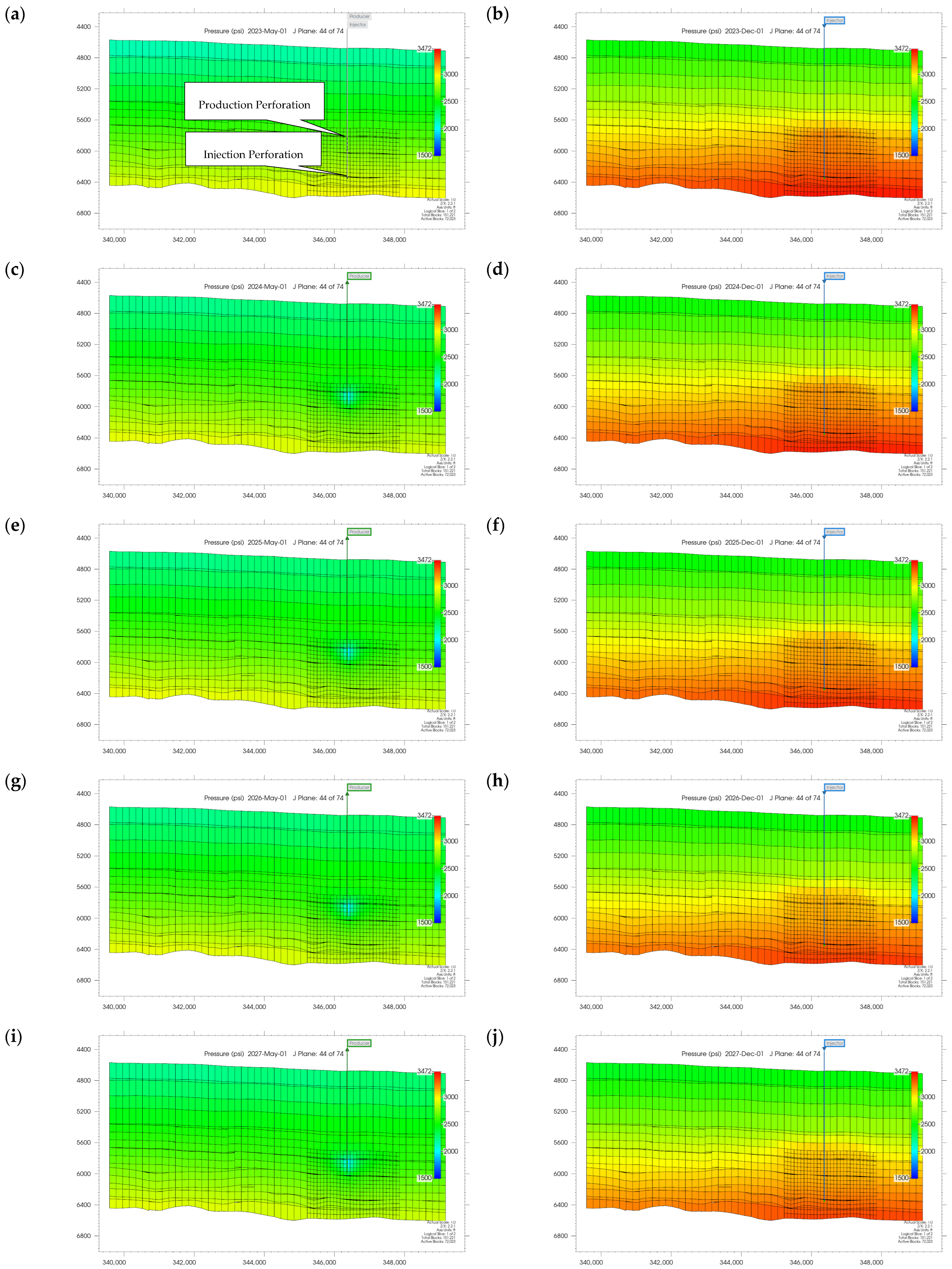

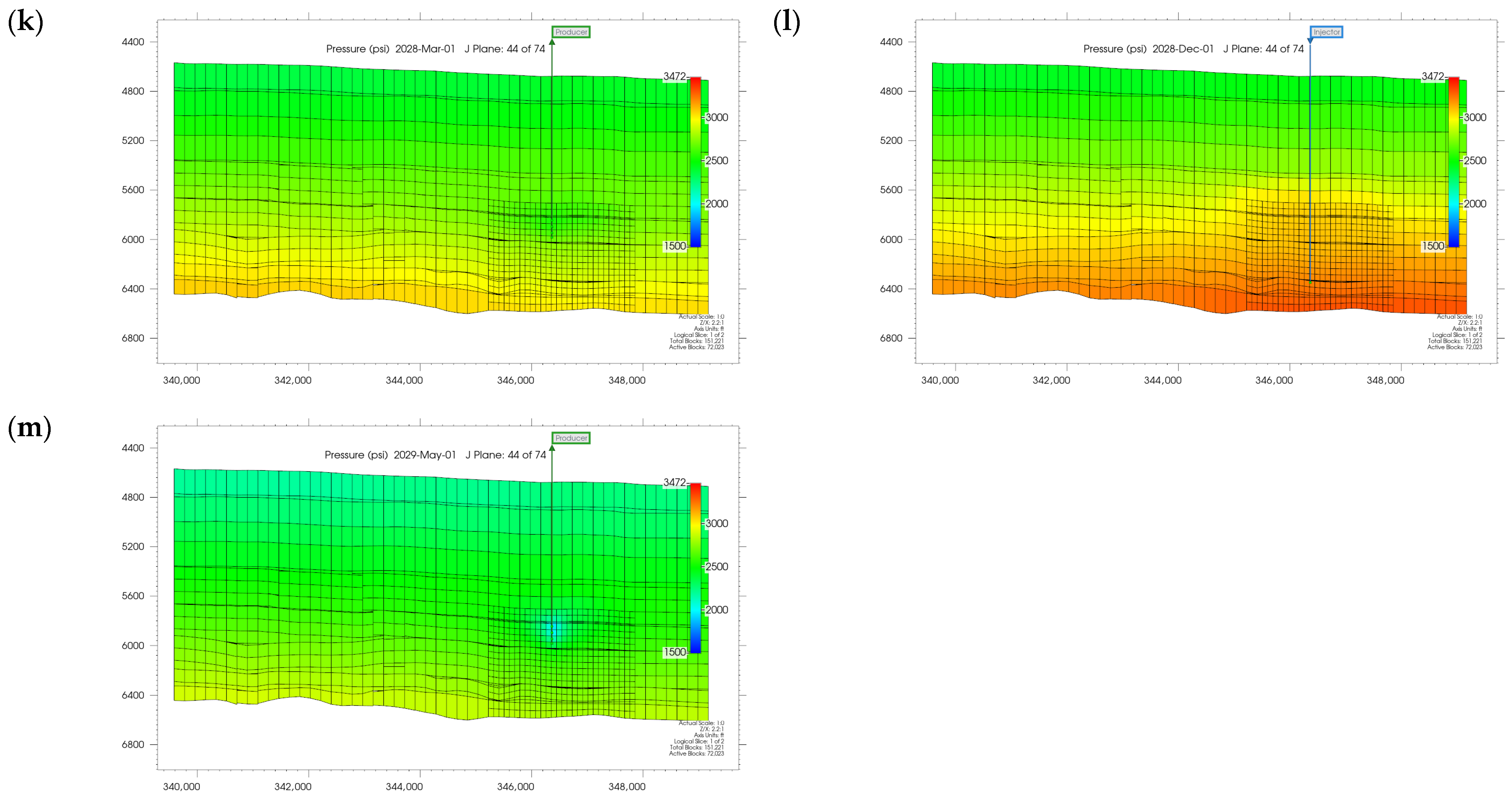

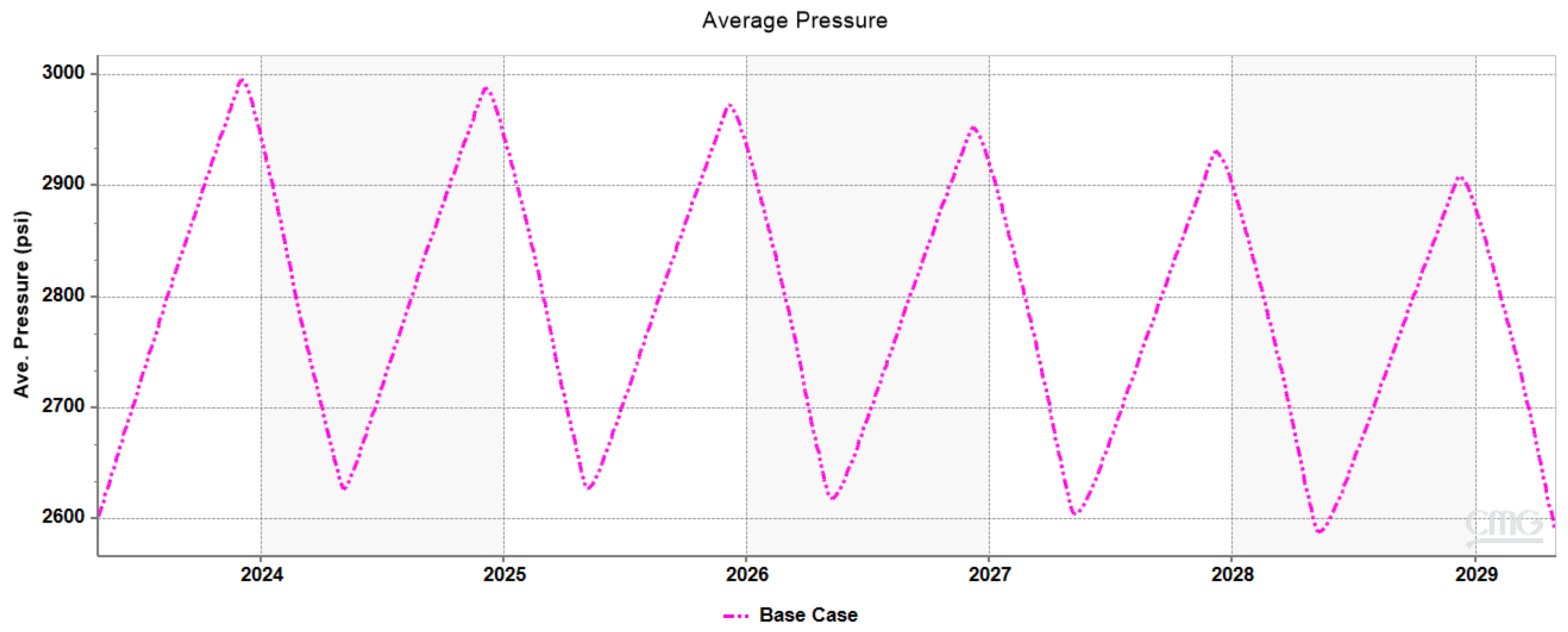

3.1. Plume Stability Analysis

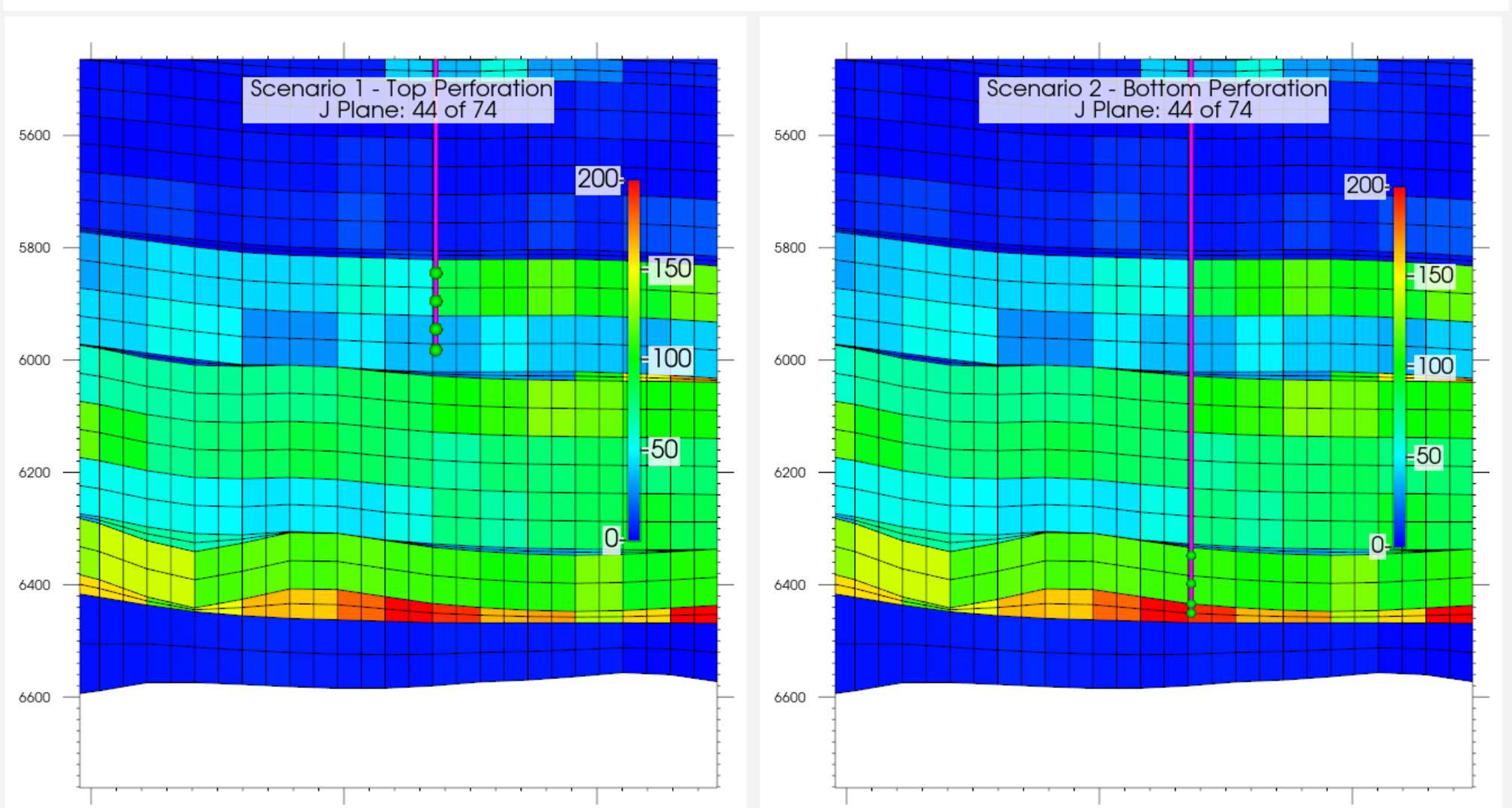

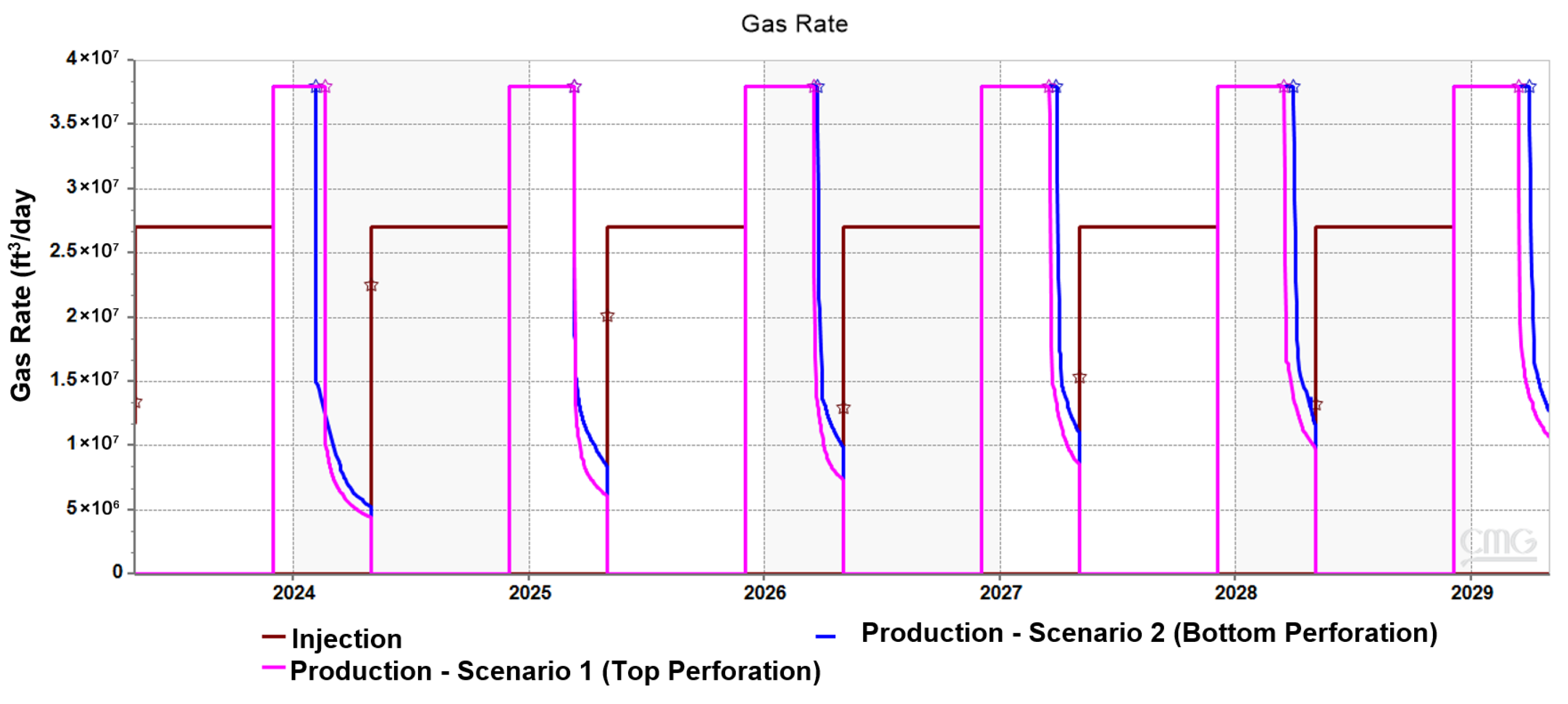

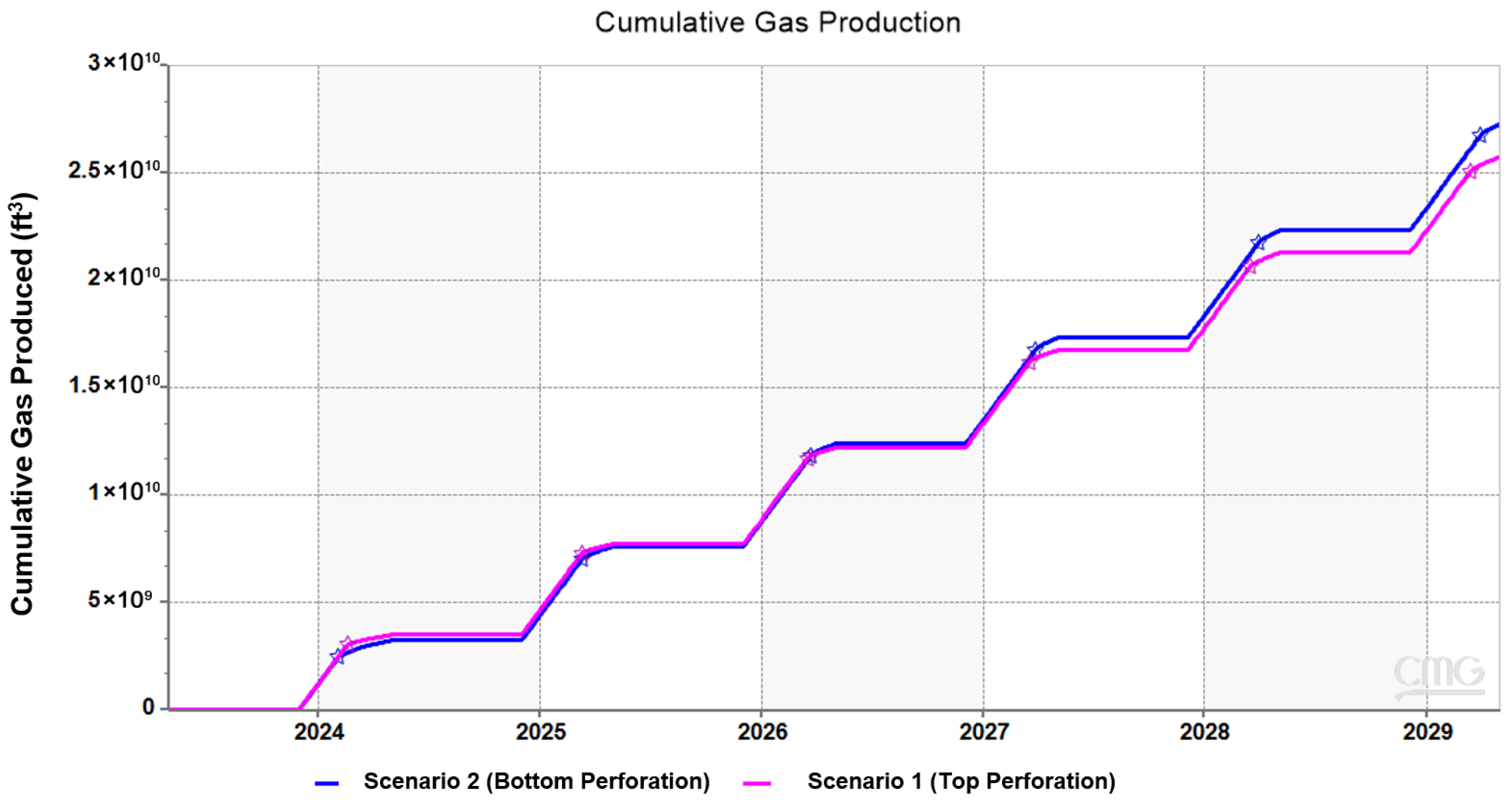

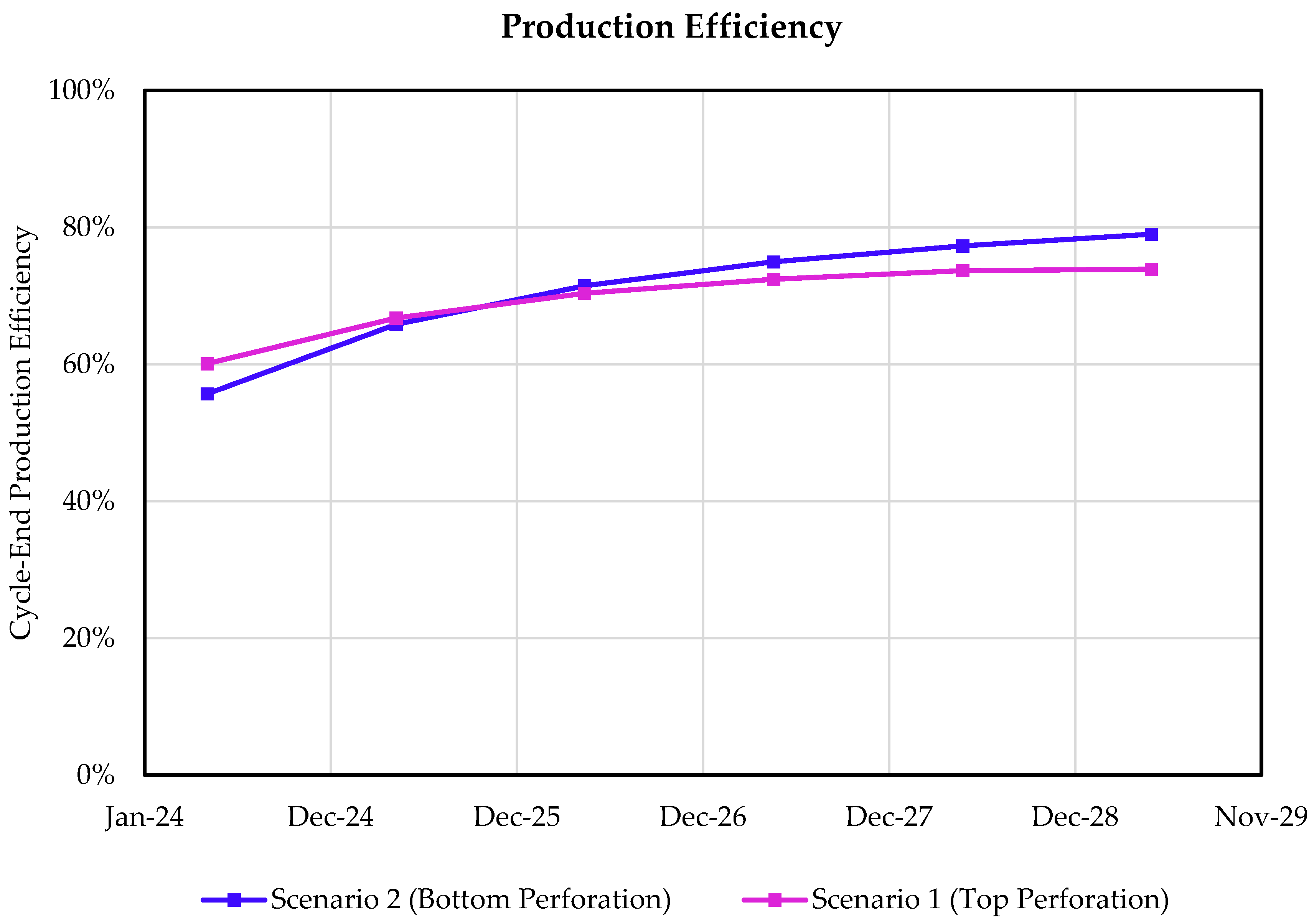

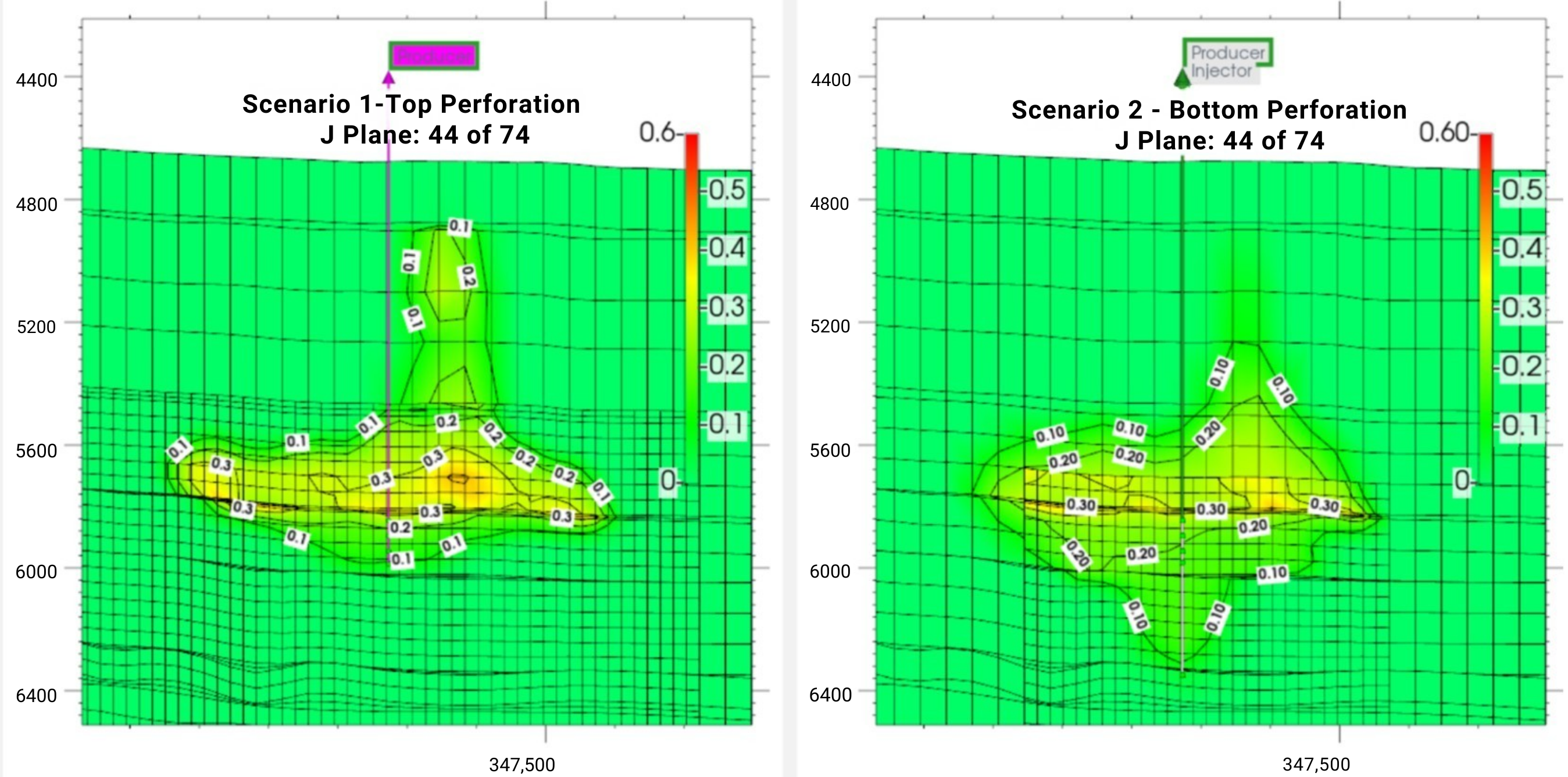

3.2. Effect of Injection Well Perforation Location on Withdrawal Efficiency

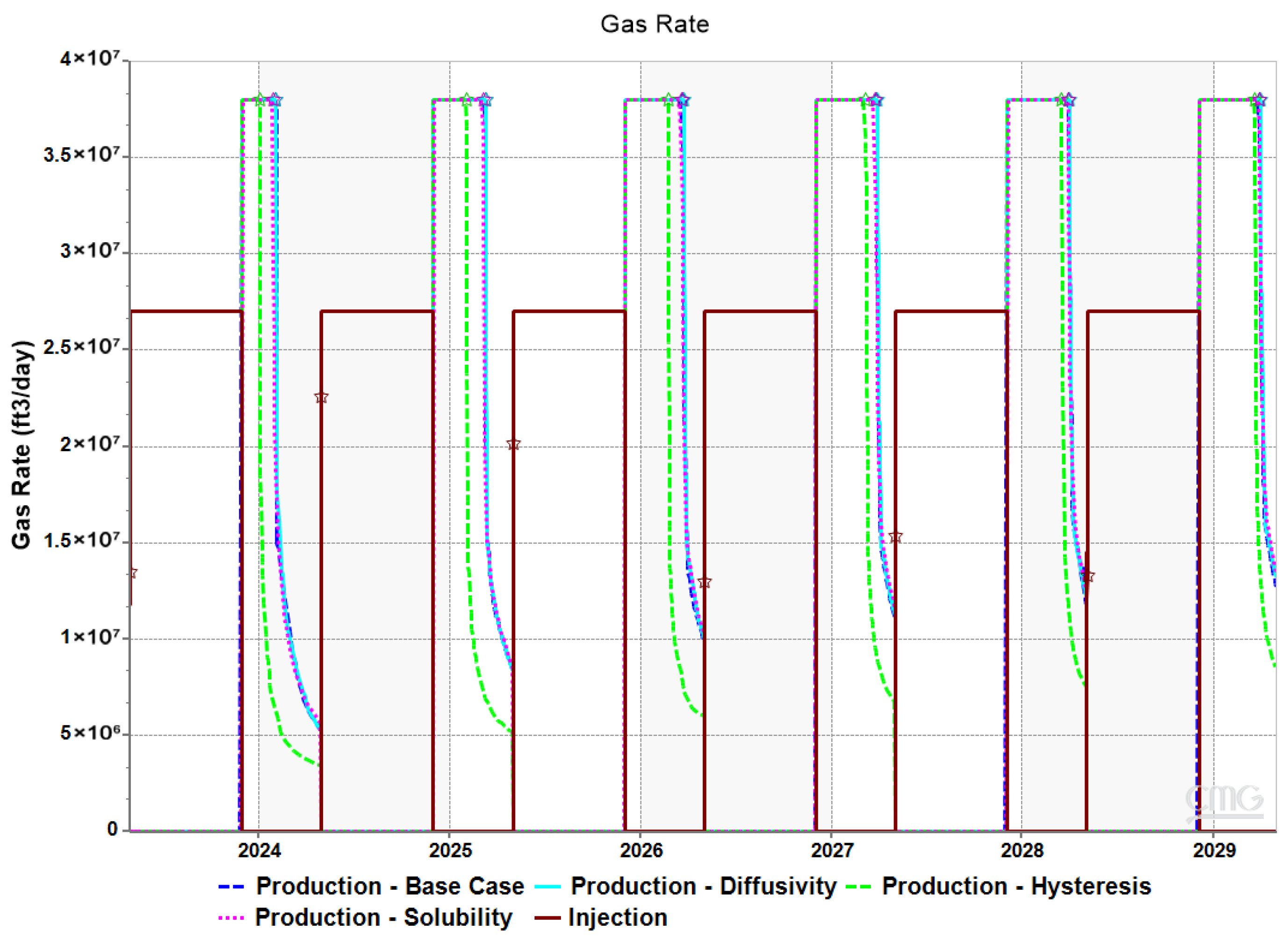

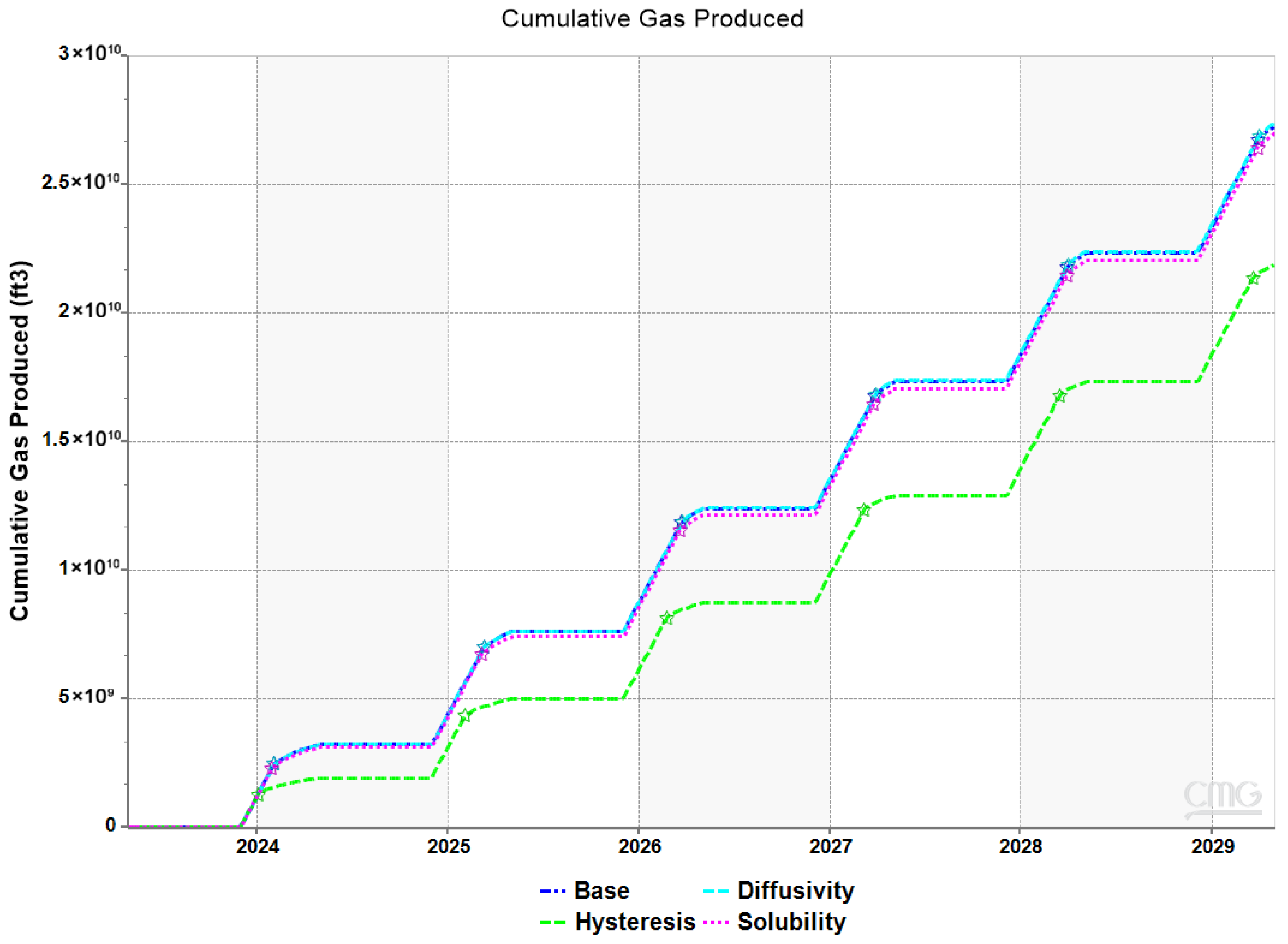

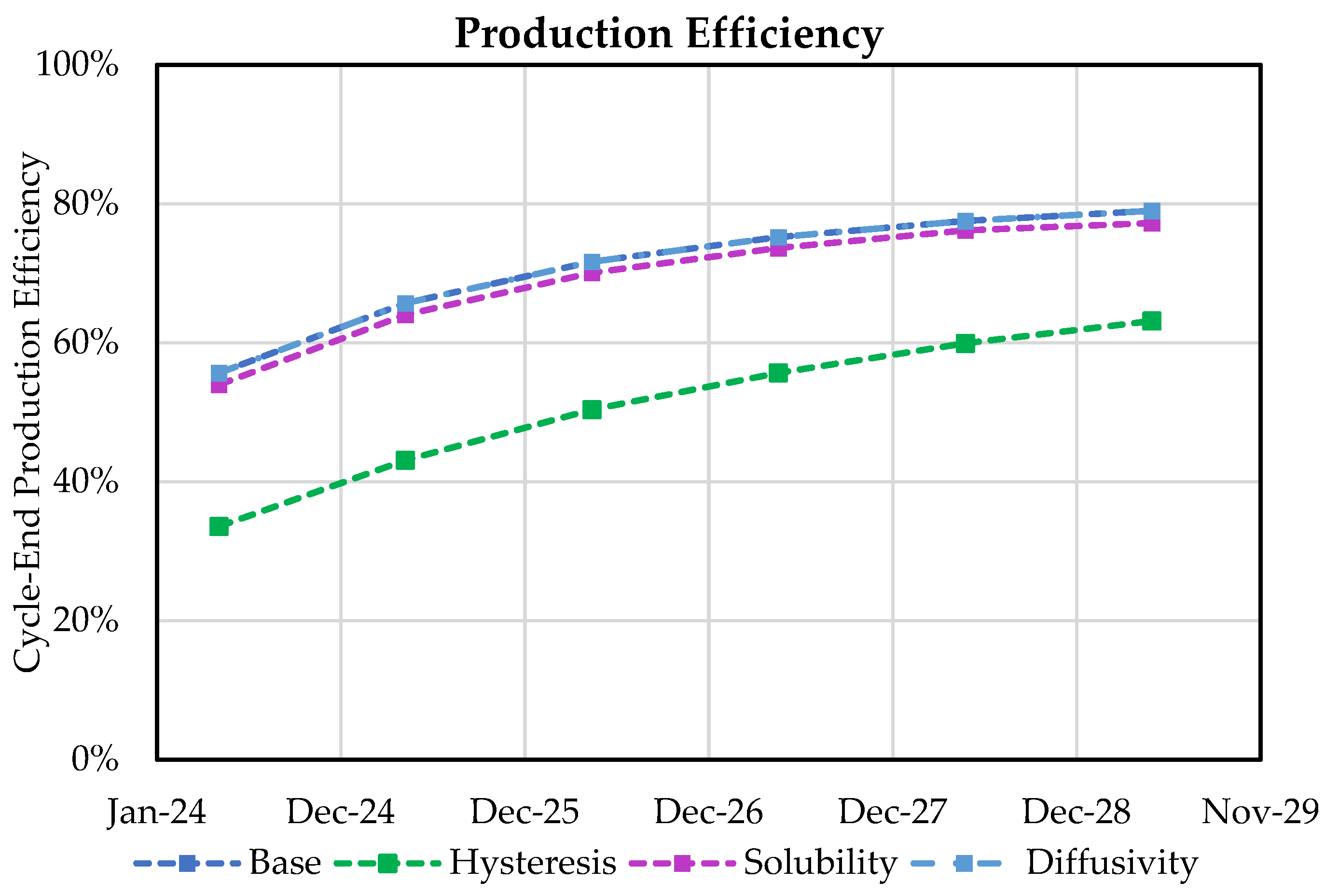

3.3. Impact of Hysteresis, Diffusivity, and Solubility on Withdrawal Efficiency

3.4. From Reservoir Simulation to Field Deployment: Practical UHS Targets and Usable Energy Measures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBDP | Illinois Basin–Decatur Project |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| UHS | Underground Hydrogen Storage |

| BTU | British Thermal Units |

| UGS | Underground Gas Storage |

References

- Allen, M.; Dube, O.P.; Solecki, W.; Aragón-Durand, F.; Cramer, W.; Humphreys, S.; Kainuma, M. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Intergov. Panel Clim. Change 2018, 677, 393. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Jiang, J.; Shi, S.; Raftery, A.E. Mitigation efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and meet the Paris Agreement have been offset by economic growth. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrae, A.S.G. Hypotheses for primary energy use, electricity use and CO2 emissions of global computing and its shares of the total between 2020 and 2030. WSEAS Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 15, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Summary—World Energy Outlook—Analysis-IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023/executive-summary (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Borowski, P.F. Renewable Energy Sources Towards a Zero-Emission Economy. Energies 2025, 18, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanayake, K.; Wickramage, I.; Samarasinghe, U.; Ranmini, Y.; Ehalapitiya, S.; Jayathilaka, R.; Yapa, S. Renewable energy as a solution to climate change: Insights from a comprehensive study across nations. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, D.; Verikios, G.; Whitten, S.; Brinsmead, T.S.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Rodriguez, S. Early transition to near-zero emissions electricity and carbon dioxide removal is essential to achieve net-zero emissions at a low cost in Australia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Smith, S.M.; Allen, M.; Axelsson, K.; Hale, T.; Hepburn, C.; Kendall, J.M.; Khosla, R.; Lezaun, J.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; et al. The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubi, E.A. Experimental and Simulation Study of Underground Hydrogen Storage; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=Pr4A0QEACAAJ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ericson, S.; Engel-Cox, J.; Arent, D. Approaches for Integrating Renewable Energy Technologies in Oil and Gas Operations; The Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis: Golden, CO, USA, 2015. Available online: www.nrel.gov/publications (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Ferro, P.; Wentz, H.; Oyen, S.; Viger, M.; Ngan, C.; Frager, C.; Mulvaney, K.; Lira, S.; Rawson, M. Imagining the hydrogen future of 2050. Interdiscip. Environ. Rev. 2015, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Acharya, S.K.; Patnaik, P.P.; Panda, B.S.; Roy, A.; Saha, S.; Singh, K.A. Low-pressure hydrogen storage using different metal hydrides: A review. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2025, 35, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahman, N.; Naser, N.; Khan, E.; Mahmood, T. Environmental science, policy, and industry nexus: Integrating Frameworks for better transport sustainability. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Alvarado, R.; Ali, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Meo, M.S. Transport infrastructure, economic growth, and transport CO2 emissions nexus: Does green energy consumption in the transport sector matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 40094–40106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolge, K.; Barisa, A.; Kirsanovs, V.; Blumberga, D. The status quo of the EU transport sector: Cross-country indicator-based comparison and policy evaluation. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck, G.S.; Hache, E.; Sabathier, J.; Guedes, F.; Reigstad, G.A.; Straus, J.; Wolfgang, O.; Ouassou, J.A.; Askeland, M.; Hjorth, I.; et al. Hydrogen and the decarbonization of the energy system in europe in 2050: A detailed model-based analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbeleye, I.; Oguntona, O.; Elegbeleye, F. Green Hydrogen: Pathway to Net Zero Green House Gas Emission and Global Climate Change Mitigation. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Oko, E.; Kuang, B.; Bello, A.; Onwualu, A.P.; Oyagha, S.; Whidborne, J. The prospects of hydrogen in achieving net zero emissions by 2050: A critical review. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 2, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.E.Q.; Santos, D.M.F. Technical and Economic Viability of Underground Hydrogen Storage. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 975–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Agarwal, S.; Jain, A. Significance of Hydrogen as Economic and Environmentally Friendly Fuel. Energies 2021, 14, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Mollaamin, F.; Monajjemi, M.; Dang, C.M. A review of 2019 fuel cell technologies: Modelling and controlling. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 17, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Dosapati, S.H. Hydrogen storage system integrated with fuel cell. Prog. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedani, E.A.; Alenabi, S.A.; Talebi, S. Hydrogen as an energy source: A review of production technologies and challenges of fuel cell vehicles. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3778–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooni, I.K.; Dzogbewu, T.C. Hydrogen Economy and Climate Change: Additive Manufacturing in Perspective. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, C.; Soliman, I.; Panthi, D.; Tandler, P.; Fatani, O.; Ghulamullah, N.A.; Marasinghe, D.; Farhath, M.; Madhujith, T.; Conrad, K.; et al. A comprehensive review on hydrogen production, storage, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 10900–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinkumar, T.M.; Bharatiraja, C. Sustainable hydrogen energy fuel cell electric vehicles: A critical review of system components and innovative development recommendations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 215, 115601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethia, H.; Priyam, A. Review on hydrogen fuel cells as an alternative fuel. Next Energy 2025, 9, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.H.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, J.; Cañas-Carretón, M.; Carrión, M.; Hernández-Labrado, G.R.; Merino, C.; Muñoz, J.I.; Zárate-Miñano, R. Integrating Hydrogen into Power Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, N.; Fereidani, N.A.; Cardoso, B.J.; Martinho, N.; Gaspar, A.; da Silva, M.G. Advances in hydrogen blending and injection in natural gas networks: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.; Deane, P.; Yousefian, S.; Monaghan, R.F.D. The hydrogen storage challenge: Does storage method and size affect the cost and operational flexibility of hydrogen supply chains? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekwe, I.M.S.; Mustapha, S.I.; Akpasi, S.O.; Tetteh, E.K.; Joel, A.S.; Isa, Y.M. The hydrogen challenge: Addressing storage, safety, and environmental concerns in hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ospino, R.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Strategies to recover and minimize boil-off losses during liquid hydrogen storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.M.; Khaira, A.M. A mini-review on liquid air energy storage system hybridization, modelling, and economics: Towards carbon neutrality. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 26380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati, S.; Gomari, S.R.; Gasanzade, F.; Bauer, S.; Pak, T.; Orr, C. Underground hydrogen storage to balance seasonal variations in energy demand: Impact of well configuration on storage performance in deep saline aquifers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 26894–26910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girhe, P.; Barai, D.P.; Bhanvase, B.A.; Gharat, S.H. A Review on Functional Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Energy Storage 2025, 7, e70218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baru, A.M.; Eyitayo, S.I.; Okere, C.J.; Baru, A.; Watson, M.C. Large-Scale Hydrogen Storage in Deep Saline Aquifers: Multiphase Flow, Geochemical–Microbial Interactions, and Economic Feasibility. Materials 2025, 18, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdin, Z.; Khalilpour, K.; Catchpole, K. Projecting the levelized cost of large scale hydrogen storage for stationary applications. Energy Convers Manag. 2022, 270, 116241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 3: LCI Hydrogen—Connecting Infrastructure. In Harnessing Hydrogen: A Key Element of the U.S. Energy Future. National Petroleum Council, 2025. Available online: https://harnessinghydrogen.npc.org/documents/H2-Ch_3-Connecting_Infrastructure-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Małachowska, A.; Łukasik, N.; Mioduska, J.; Gębicki, J. Hydrogen Storage in Geological Formations—The Potential of Salt Caverns. Energies 2022, 15, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, M.F.; Khanal, A.; Khan, M.I.; Pandey, R. Current status of underground hydrogen storage: Perspective from storage loss, infrastructure, economic aspects, and hydrogen economy targets. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zandanel, A.; Liu, S.; Neil, C.W.; Germann, T.C.; Gross, M.R. Temperature dependence of hydrogen diffusion in reservoir rocks: Implications for hydrogen geologic storage. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 2051–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstad, D.; Gardarsdottir, S.; Roussanaly, S.; Voldsund, M.; Ishimoto, Y.; Nekså, P. Liquid hydrogen as prospective energy carrier: A brief review and discussion of underlying assumptions applied in value chain analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, E.R.; Salehi, S. A Review on Well Integrity Issues for Underground Hydrogen Storage. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. ASME 2021, 144, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duartey, K.O.; Ampomah, W.; Rahnema, H.; Mehana, M. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Transforming Subsurface Science into Sustainable Energy Solutions. Energies 2025, 18, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, L.; Hidalgo, J.C.; Strąpoć, D.; Moretti, I. H2 Transport in Sedimentary Basin. Geosciences 2025, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta, E.; Kovács, T.; Herrera-Franco, G.; Caicedo-Potosí, J.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Ordóñez-Casado, B.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Carneiro, J. Laboratory Studies on Underground H2 Storage: Bibliometric Analysis and Review of Current Knowledge. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglauer, S.; Ali, M.; Keshavarz, A. Hydrogen Wettability of Sandstone Reservoirs: Implications for Hydrogen Geo-Storage. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, L.K.; Kiran, R.; Okoroafor, E.R.; Wood, D.A. Review of reservoir challenges associated with subsurface hydrogen storage and recovery in depleted oil and gas reservoirs. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, C. Title Investigation of CO2 Plume Behavior for a Large-Scale Pilot Test of Geologic Carbon Storage in a Saline Formation Investigation of CO2 Plume Behavior for a Large-Scale Pilot Test of Geologic Carbon Storage in a Saline Formation. Transp. Porous Media 2010, 82, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemme, C.; Berk, W. Hydrogeochemical Modeling to Identify Potential Risks of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Fields. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Park, H.; Shi, J.; Kiyama, T.; Lei, X.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Y. Tracking CO2 Plumes in Clay-Rich Rock by Distributed Fiber Optic Strain Sensing (DFOSS): A Laboratory Demonstration. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, C.; Patwardhan, S.D.; Iglauer, S.; Mahmud, H.B.; Ali, M.F.J. A Critical Review on Parameters Affecting the Feasibility of Underground Hydrogen Storage. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11658–11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Homoud, R.; Machado, M.V.B.; Daigle, H.; Sepehrnoori, K.; Ates, H. Enhancing Hydrogen Recovery from Saline Aquifers: Quantifying Wettability and Hysteresis Influence and Minimizing Losses with a Cushion Gas. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S.P.; Barnett, M.J.; Field, L.P.; Milodowski, A.E. Subsurface Microbial Hydrogen Cycling: Natural Occurrence and Implications for Industry. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, Q.T.; Keshavarz, A.; Behrenbruch, P.; Iglauer, S. Hydrogen diffusion into water and cushion gases—Relevance for hydrogen geo-storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 98, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Isah, A.; Yekeen, N.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Okoroafor, E.R.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Mahmoud, M.; Vahrenkamp, V.; Hoteit, H. Recent progress in underground hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 5740–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchev, M.; Martinez-Morales, A.A.; Lim, T.; Raju, A.S.K.; Yilmaz, M.; Akinci, T.C. Leakage rates of hydrogen-methane gas blends under varying pressure conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 143, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubi, E.A.; Rahnema, H.; Koray, A.-M.; Shabani, B. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Steady-State Measurement of Hydrogen–Brine Relative Permeability with Gas Slip Correction. Gases 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Song, Z.; Wang, J. Stability Analysis on the Long-Term Operation of the Horizontal Salt Rock Underground Storage. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6674195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yu, S.; Wong, L.N.Y. Long-term stability forecasting for energy storage salt caverns using deep learning-based model. Energy 2025, 319, 134854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati, S.; Gomari, S.R. Designing Geometrically Stable Salt Caverns for Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Case Study from Northeast England. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 17067–17082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. Research on the Stability of Salt Cavern Hydrogen Storage and Natural Gas Storage under Long-Term Storage Conditions. Processes 2024, 12, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, L.; Blunt, M.; Hajibeygi, H. Pore-scale modelling and sensitivity analyses of hydrogen-brine multiphase flow in geological porous media. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chakrapani, T.H.; Wen, Z.; Hajibeygi, H. Pore-Scale Simulation of H2-Brine System Relevant for Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Lattice Boltzmann Investigation. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 190, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Numerical simulation of the impact of different cushion gases on underground hydrogen storage in aquifers based on an experimentally-benchmarked equation-of-state. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 50, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Chen, Z.; Nourozieh, H.; Yang, M. Numerical simulation of large-scale seasonal hydrogen storage in an anticline aquifer: A case study capturing hydrogen interactions and cushion gas injection. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, N.; Scafidi, J.; Pickup, G.; Thaysen, E.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Satterley, A.; Booth, M.; Edlmann, K.; Haszeldine, R. Hydrogen storage in saline aquifers: The role of cushion gas for injection and production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39284–39296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rhouma, S.; Dos Santos, A.; Veloso, F.d.M.L.; Smai, F.; Chiquet, P.; Masson, R.; Broseta, D. H2 storage with CO2 cushion gas in aquifers: Numerical simulations and performance influences in a realistic reservoir model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 110, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Moridis, G.J.; Blasingame, T.A.; Abdulkader, A.M.; Yan, B. Compositional reservoir simulation of underground hydrogen storage in depleted gas reservoirs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 36035–36050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Muhammed, N.S.; Okolie, J.A.; Epelle, E.I. A sensitivity study of hydrogen mixing with cushion gases for effective storage in porous media. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 1353–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBDP. Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS), Illinois Basin—Decatur Project (IBDP) Well Information, 30 April 2021. Midwest Geological Sequestration Consortium (MGSC) Phase III Data Sets. DOE Cooperative Agreement No. DE-FC26-05NT42588. Submissions—EDX. Available online: https://edx.netl.doe.gov/dataset/illinois-state-geological-survey-isgs-illinois-basin-decatur-project-ibdp-well-information (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Freiburg, J.T.; Morse, D.G.; Leetaru, H.E.; Hoss, R.P.; Yan, Q. A Depositional and Diagenetic Characterization of the Mt. Simon Sandstone at the Illinois Basin-Decatur Project Carbon Capture and Storage Site, Decatur, Illinois, USA. 2014. Available online: http://www.isgs.illinois.edu (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- NETL. Illinois Basin-Decatur Project. 2017. Available online: https://www.netl.doe.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/Illinois-Basin-Decatur-Project.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Jones, R.A.; McKaskle, R.W. Design and operation of compression system for one million tonne CO2 sequestration test. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.H.; Ii, R.A.L.; Keating, E.; Carroll, S.; Iranmanesh, A.; Mansoor, K.; Wimmer, B.; Zheng, L.; Shao, H.; Greenberg, S.E. Application of the Aquifer Impact Model to support decisions at a CO2 sequestration site. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leetaru, H.E.; McBride, J.H. Reservoir uncertainty, Precambrian topography, and carbon sequestration in the Mt. Simon Sandstone, Illinois Basin. Environ. Geosci. 2009, 16, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, B.; Lu, P.; Kammer, R.; Zhu, C. Effects of Hydrogeological Heterogeneity on CO2 Migration and Mineral Trapping: 3D Reactive Transport Modeling of Geological CO2 Storage in the Mt. Simon Sandstone, Indiana, USA. Energies 2022, 15, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.R.; Rupp, J.A. Reservoir characterization and lithostratigraphic division of the Mount Simon Sandstone (Cambrian): Implications for estimations of geologic sequestration storage capacity. Environ. Geosci. 2012, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, C.S. Calculation of Imbibition Relative Permeability for Two- and Three-Phase Flow From Rock Properties. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1968, 8, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, E.J.; Juanes, R.; Blunt, M.J.; Orr, F.M. A New Model of Trapping and Relative Permeability Hysteresis for All Wettability Characteristics. SPE J. 2008, 13, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, W. Experiments on the quantity of gases absorbed by water, at different temperatures, and under different pressures. Abstr. Pap. Print. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1832, 1, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Babarinde, O.O.; Okwen, R.; Frailey, S.M.; Whittaker, S.G. Modeling commercial-scale CO2 injection in Mt. Simon Sandstone near Decatur, IL storage sites. In Proceedings of the 14th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference Melbourne 21–26 October 2018 (GHGT-14), Melbourne, Australia, 21–26 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, N.; Alcalde, J.; Miocic, J.M.; Hangx, S.J.T.; Kallmeyer, J.; Ostertag-Henning, C.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Thaysen, E.M.; Strobel, G.J.; Schmidt-Hattenberger, C.; et al. Enabling large-scale hydrogen storage in porous media—The scientific challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Birkholzer, J.T.; Mehnert, E.; Lin, Y.F.; Zhang, K. Modeling basin- and plume-scale processes of CO2 storage for full-scale deployment. Ground Water 2010, 48, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, M.; Zheng, F.; Jha, B. Hydrogen leakage via caprock fracturing and fault reactivation during subsurface porous media storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 149, 149786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Jensen, J.; Duncan, I.; Lake, L. Buoyant Flow of H2 Vs. CO2 in Storage Aquifers: Implications to Geological Screening. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2023, 26, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development. Energies 2025, 18, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakulin, A.; Swaminadhan, S.; Shuster, M. Instrumenting the Devine Site as a Field Laboratory for Hydrogen Injection: Characterization and Monitoring Feasibility Assessment. In Proceedings of the International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy (IMAGE 2025), Houston, TX, USA, 25–28 August 2025; Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA; Boris Gurevich, Curtin University: Bentley, WA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Pei, P. Evaluation of the Influencing Factors of Using Underground Space of Abandoned Coal Mines to Store Hydrogen Based on the Improved ANP Method. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 7506055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysyy, M.; Fernø, M.A.; Ersland, G. Effect of relative permeability hysteresis on reservoir simulation of underground hydrogen storage in an offshore aquifer. J. Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Liu, K.; Ren, B.; Zhang, M.; Ju, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhang, X.; Clarkson, C.R.; Edlmann, K.; Zhu, W.; et al. Impacts of relative permeability hysteresis, wettability, and injection/withdrawal schemes on underground hydrogen storage in saline aquifers. Fuel 2022, 333, 126516. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016236122033403?casa_token=YS9NxjJB3pIAAAAA:7wtJ8-YMMmSTp01X5Jy2wlXYI9BS45m253TNqRsguj17O6MSJLkc3tabfKxMTrC6Asy-mXwPIi8 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Nazari, F.; Nafchi, S.A.; Asbaghi, E.V.; Farajzadeh, R.; Niasar, V.J. Impact of capillary pressure hysteresis and injection-withdrawal schemes on performance of underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 50, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, D.S.; Al-Khdheeawi, E.A.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Iglauer, S. Hydrogen underground storage efficiency in a heterogeneous sandstone reservoir. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2021, 5, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Arif, M.; Glatz, G.; Mahmoud, M.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Alafnan, S.; Iglauer, S. A holistic overview of underground hydrogen storage: Influencing factors, current understanding, and outlook. Fuel 2022, 330, 125636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, I.I.; Zivar, D.; Ayatollahi, S.; Mahani, H. The effect of gas solubility on the selection of cushion gas for underground hydrogen storage in aquifers. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.S.A. A review of underground hydrogen storage in depleted gas reservoirs: Insights into various rock-fluid interaction mechanisms and their impact on the process integrity. Fuel 2022, 334, 126677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, M.; Salina Borello, E.; Bocchini, S.; Pirri, C.F.; Verga, F.; Coti, C.; Scapolo, M.; Barbieri, D.; Viberti, D. Solubility of H2-CH4 mixtures in brine at underground hydrogen storage thermodynamic conditions. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1356491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina Borello, E.; Bocchini, S.; Chiodoni, A.; Coti, C.; Fontana, M.; Panini, F.; Peter, C.; Pirri, C.F.; Tawil, M.; Mantegazzi, A.; et al. Underground Hydrogen Storage Safety: Experimental Study of Hydrogen Diffusion through Caprocks. Energies 2024, 17, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, C. Multiscale experimental and numerical study on hydrogen diffusivity in salt rocks and interlayers of salt cavern hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 79, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, S.R.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Patange, P.; Watson, M. A comprehensive review of the mechanisms and efficiency of underground hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Pilot STorage for Large Ecosystem Replication. Available online: https://www.era.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/02_Leadbetter_Storengy.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Glöckner, M.; Hevin, G. Model Qualification of Test Caverns on Field Test Data. Available online: https://hypster-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/D2.6_Model_qualification.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Boon, M.; Hajibeygi, H. Experimental characterization of H2/water multiphase flow in heterogeneous sandstone rock at the core scale relevant for underground hydrogen storage (UHS). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaseri, A.; Esteban, L.; Giwelli, A.; Sarout, J.; Lebedev, M.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Initial and residual trapping of hydrogen and nitrogen in Fontainebleau sandstone using nuclear magnetic resonance core flooding. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 22482–22494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.K.; Al-Yaseri, A.; Ghasemi, M.; Al-Bayati, D.; Lebedev, M.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Pore scale investigation of hydrogen injection in sandstone via X-ray micro-tomography. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021, 46, 34822–34829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangda, Z.; Menke, H.; Busch, A.; Geiger, S.; Bultreys, T.; Lewis, H.; Singh, K. Pore-scale visualization of hydrogen storage in a sandstone at subsurface pressure and temperature conditions: Trapping, dissolution and wettability. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 629, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIA. Electricity Use in Homes—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/electricity-use-in-homes.php (accessed on 2 October 2025).

| System | Group | Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Ordovician | Maquoketa | Brainard |

| Ft. Atkinson | ||

| Scales | ||

| Galena | Kimmswick | |

| Decorah | ||

| Platteville | ||

| Ancell | Joachim | |

| St. Peter | ||

| Praire du Chien | Shakoppee | |

| New Richmond | ||

| Oneota | ||

| Gunter | ||

| Cambrian | Knox | Eminence |

| Potosi | ||

| Franconia | ||

| Ironton-Galesville | ||

| Eau Claire | ||

| Mt. Simon | ||

| Precambrian |

| Grid Size, ft | Simulation Time, s |

|---|---|

| 50 × 50 | 97,181 |

| 100 × 100 | 1361 |

| 200 × 200 | 819 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Appiah Kubi, E.; Rahnema, H.; Koray, A.-M.; Shabani, B. Underground Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: A Simulation Case Study in the Midwest United States. Eng 2026, 7, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010024

Appiah Kubi E, Rahnema H, Koray A-M, Shabani B. Underground Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: A Simulation Case Study in the Midwest United States. Eng. 2026; 7(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleAppiah Kubi, Emmanuel, Hamid Rahnema, Abdul-Muaizz Koray, and Babak Shabani. 2026. "Underground Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: A Simulation Case Study in the Midwest United States" Eng 7, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010024

APA StyleAppiah Kubi, E., Rahnema, H., Koray, A.-M., & Shabani, B. (2026). Underground Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: A Simulation Case Study in the Midwest United States. Eng, 7(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010024