1. Introduction

The development of digital technologies has led to rapid growth in information devices for various purposes operating without a connection to stationary power systems. Nowadays, the use of wireless sensor networks (WSNs) is one of the main directions of technology development [

1,

2,

3]. However, the organization of WSNs is associated with a number of problems, where one of the most serious is the autonomous power supply of the network nodes. The most appropriate way to construct these networks is to use independent small-sized devices, which are able to generate electrical energy directly at the location of WSN nodes [

4,

5,

6,

7]. One of the most promising types of such microgenerators (or energy harvesters) is the electrostatic microelectromechanical generator (harvester), which converts the energy of mechanical motion or vibrations into electrical energy [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The design of electrostatic microelectromechanical generators (EMGs) typically focuses on maximizing their generated electrical power. Since the energy that can be stored by a capacitor and subsequently extracted from it is proportional to the square of the voltage across the capacitor, the operating voltage in EMGs can be increased up to several hundred volts [

18,

23,

24].

However, most modern electronic devices (EMG energy consumers) use power supply voltages of less than 10 V. As a result, connecting them directly to the “high-voltage” EMGs requires an additional matching device that lowers the EMG’s output voltage [

9,

17,

18,

19,

25].

In the field of power electronics, a large number of AC/DC and DC/DC converters, voltage dividers, and multipliers have been proposed. The characteristic features of their operation are as follows: (1) operation using a primary energy source with infinite power (bus of infinite power), in which the characteristics do not change significantly when the converter is connected, and (2) the use of microprocessor control circuits.

However, the output power produced by typical EMGs is usually only a few tens of microwatts. As a result, when a voltage divider is connected to them, the characteristics of the EMG (as a primary voltage source) change. Therefore, it is not possible to rely on the stability of the primary voltage source characteristics when connecting a divider to an EMG. It should also be noted that the output resistance of energy sources with infinite power, in most cases, has an inductive nature, while the output resistance of EMGs has a capacitive nature.

In addition, in power electronics, during operation at high capacities (from units to hundreds of kilowatts), losses in converter control systems (units of watts) are not very significant. Therefore, in order to achieve good converter performance, complex control circuits are used in power electronics, which are not acceptable during the operation of EMGs. As a result, it is not possible to use circuits designed for power electronics in microsystem engineering without careful analysis and investigation of their operating features. Therefore, the search for new schemes and approaches to solve this problem continues [

9,

10,

17,

18,

19,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

For this purpose, it is proposed to use Zener diodes [

9,

28,

29], the periodic connection of the microgenerator (MG) to the load with an adjustable duty cycle (PWM conversion) [

10,

19], and circuits based on switchable capacitors [

9,

30,

39,

40]. An interesting scheme was proposed and investigated in [

31], where both voltage reduction (Dickson charge-pump) and periodic connection to the load were used, enabling users to change the duration of the MG connection to the load and, consequently, the average voltage across the load during the conversion period.

Unfortunately, these studies have focused on estimates of the output power, but the efficiency of these circuits has not been studied. So, it is not possible to compare the efficiency and losses in the proposed converters without additional investigations.

However, the analysis of circuits with Zener diodes [

9,

28,

29] and switchable capacitors [

9,

30,

39,

40] for voltage reduction shows that, for these circuits, when the load is connected, part of the energy generated by the EMG is not transferred to the load but is instead lost uselessly. Thus, the voltage reduction is mainly achieved by means of the losses of the energy generated by the EMG, and these losses are primarily caused by converter losses.

As for the EMGs, where special control circuits were used to adjust the connection time of the microgenerator to the load [

10,

19], the analysis performed in [

19] showed that the power consumption of the control circuit in the proposed configuration was about 97.2 µW. This value is too high for such a control circuit to be used in microgenerators. In order to reduce energy consumption, the authors suggested reducing the duration of the load connection phase. They showed that when the duration of the load connection phase was reduced to 0.005% of the total cycle duration (the control circuit remained mostly in sleep mode), the power consumption of the control circuit was reduced to 1.03 µW, which can be acceptable for use in EMGs. However, this significantly reduces the power produced by the system.

Thus, for the proposed schemes, in any case, part of the generated energy is lost together with voltage reduction. In our opinion, circuits based on switchable capacitors seem to be the most promising for converting high AC voltage generated by the EMGs into low DC voltage [

32,

33].

The conversion principle of the high AC voltage of a primary power source into a low DC voltage in such circuits is based on voltage division using switchable capacitors. In the conversion process,

N capacitors connected in series are initially charged from the primary voltage source, and then these capacitors are reconfigured into a parallel connection and discharged to the load [

41]. It is assumed in this case that the load voltage will be approximately

N times lower than the amplitude value of the primary voltage source.

In [

32,

33], we have investigated the operation of the diode–capacitor voltage divider with a low-power primary energy source. It was established that, during analysis of the operation of the diode–capacitor voltage divider based on switchable capacitors, it is necessary to consider the reverse capacitances of the discharging diodes, which can significantly affect the divider’s operation. It was found that the division ratio of the diode–capacitor voltage divider did not remain constant, but significantly depended on the load resistance, and the capacitances of the discharging diodes. Therefore, the practical performance of the diode–capacitor voltage divider circuit differs from the “ideal” theoretical analysis and the assumptions commonly made in power electronics. As a result, if the load resistance changes, the parameters of the diode–capacitor voltage divider need to be recalculated. Furthermore, the considered circuit had quite significant energy losses.

In power electronics for reducing losses, instead of a circuit with diode–capacitor commutation of switchable capacitors, a transformerless voltage divider circuit with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors is proposed [

41,

42,

43]. Taking the main features of its operation into account, it still remains unclear how this circuit will operate with a low-power primary energy source.

This paper is dedicated to the study of operation features of the voltage divider circuits with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors designed to work as a part of low-power EMGs, and other low-power autonomous electronic systems, with reduced output voltage.

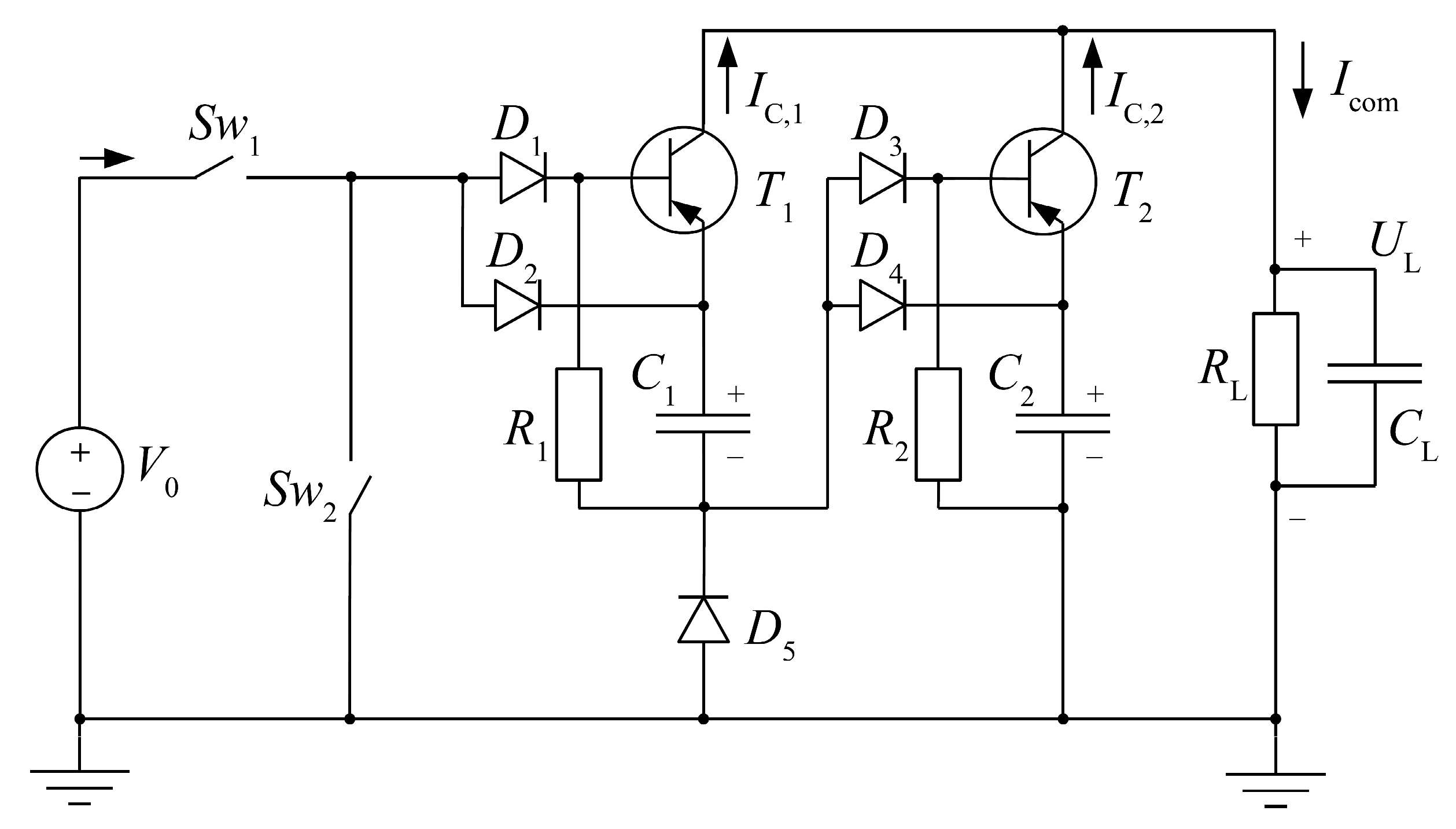

2. Analysis of the Voltage Divider Operation with Transistor–Diode Commutation of Capacitors

An original structure of the three-stage transformerless voltage divider with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors, and one charging switch, which simplifies the control system, was proposed in [

41] (

Figure 1a). Simplification is achieved because the control of the charging

VT2,1 and discharging

VT1,i transistor switches is carried out by the same generator of rectangular pulses

U2,1.

In the operation of this voltage divider, the authors [

41] distinguish two cycles. In the first cycle (transistor

VT2,1 is switched on), the in-series-connected capacitors

Ci are being charged from the primary voltage source

V0 (

Figure 1b). At the same time, since the voltage across the resistors

Ri exceeds the voltage across the capacitors

Ci, the discharging transistors

VT1,i are turned off. In the second cycle (transistor

VT2,1 is switched off), the transistor switches

VT1,i are turned on by the discharging current of capacitors

Ci through their base–emitter junctions and limiting resistors

Ri. At the same time, the capacitors

Ci connected in parallel are discharged through the

RLCL load (

Figure 1c). Then, the two-stroke operation cycle of the divider is repeated.

Such a voltage divider can be used not only in electrostatic microgenerators, but also in other systems where it is necessary to reduce the voltage.

In order to analyze the advantages and disadvantages of this circuit, we consider the operation of this voltage divider, assuming that all the circuit elements of the same type have identical values. Considering that the operation of the diode–capacitor voltage divider is significantly influenced by the reverse capacitances of the discharging diodes [

32,

33] (in this case, the diodes

VD3,1 and

VD3,2), we will take into account that the charge of their barrier capacitances changes when the discharging diodes are reverse-biased. The base–emitter junction barrier capacitances of the transistors will also be taken into account. To simplify the calculations, we will assume that the barrier capacitances do not depend on the applied voltage.

Next, for clarity, we will analyze the two-stage divider circuit and consider three cases. In the first case, we will assume that the divider is connected to an ideal voltage source V0 constantly (i.e., the primary voltage source has infinite power, circuit 1). In the second case, we will assume that the divider is also connected to an ideal voltage source V0, but periodically (circuit 2). In the third case, in comparison with the second one, we will take into account that the primary voltage source has limited power, which is inherent for EMGs (circuit 3).

3. Analysis of Circuit 1 Operation

Figure 2 shows the electrical circuit of the two-stage transformerless voltage divider with transistor–diode commutation and the primary voltage source with unlimited power. In this case, the switch

Sw1 must be permanently switched on, whereas

Sw2 must be switched off.

When the switch Sw1 is initially turned on, the voltage source V0 is connected to the divider, initiating the charging process of the capacitances C1 and C2, along with the base–emitter junction capacitances of the transistors (CBE,1 and CBE,2), and the reverse capacitance of the discharging diode D5 (CD5). Since the capacitances C1 and C2 have much higher values than the capacitances CBE,1, CBE,2, and CD5, the intrinsic capacitances of the base–emitter junctions of the transistors and the discharging diode are charged first. At the same time, the voltage across C1 and C2 remains almost zero and the capacitances CBE,1, CBE,2, and CD5 are charged to the voltages approximately equal to 0.5V0. Transistors operate in the cut-off mode and their collector currents are small. The load voltage is close to zero and increases very slowly.

During the charging process of

C1 and

C2, their voltages increase; as a result, the voltage between the base and the common wire of the first transistor becomes greater than

V0, and for the second one, greater than 0.5

V0. In this case, diodes

D1 and

D3 are reverse-biased, and the capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 begin to discharge through resistors

R1 and

R2; the locking voltages across the base–emitter (B-E) junctions of the transistors decrease, but the collector currents increase (sections

1 and

2 in

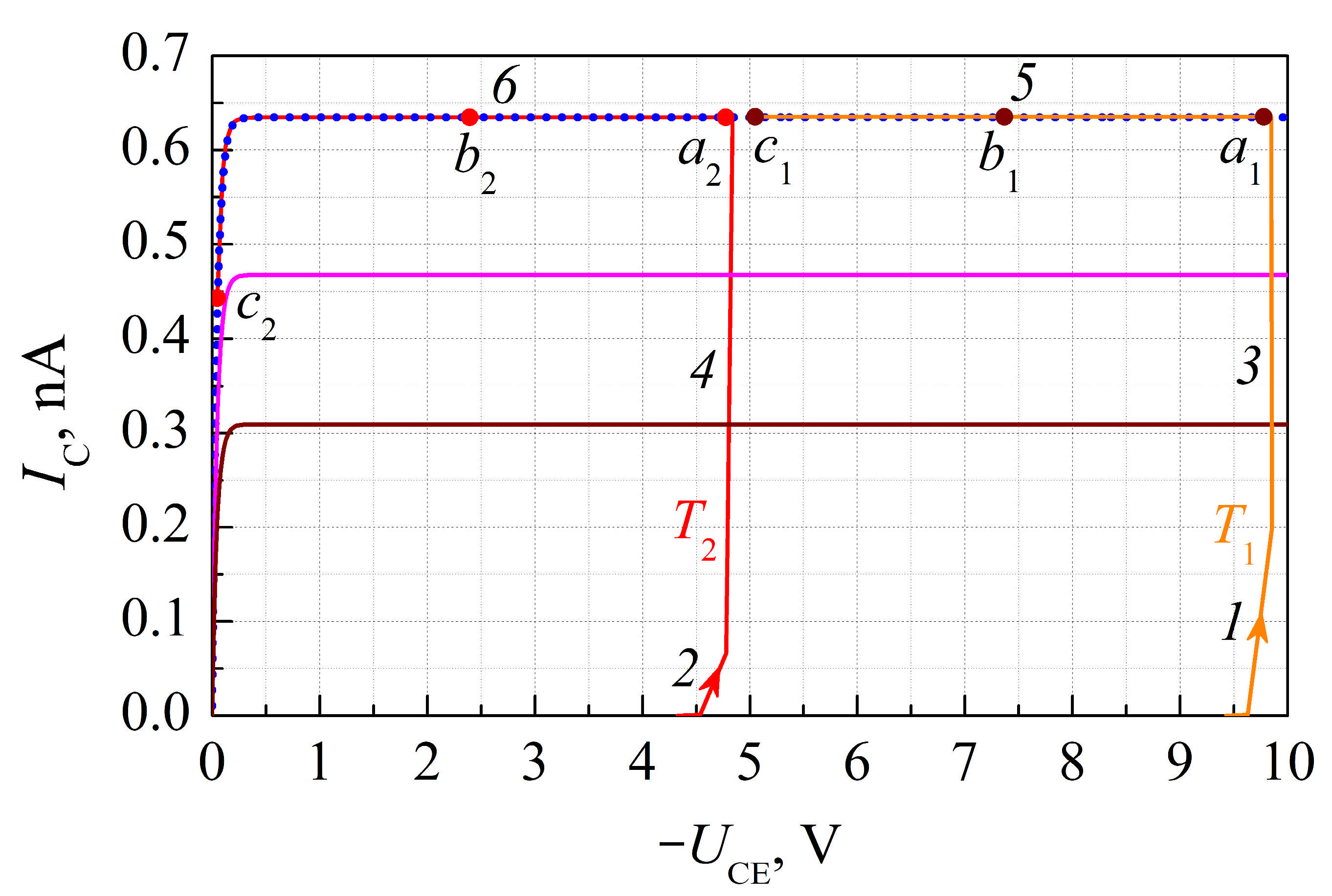

Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows the dependences of the transistor collector currents versus the collector–emitter (C-E) voltages calculated at

C1 =

C2 = 1 nF;

CL = 10 nF;

CBE,1 =

CBE,2 = 2 pF;

CD5 = 40 pF;

R1 =

R2 =

RL = 10 MΩ; and

V0 = 10 V. At the initial stage (sections

1 and

2 in

Figure 3), collector currents grow monotonously. However, on the linear scale, this growth is not immediately visible (sections

1 and

2 have horizontal sections at the beginning). Since the voltage across the load changes slowly at this stage, then, since the main capacitors

C1 and

C2 are charged, the negative C-E voltage of the transistors (

UCE) increases in absolute value.

As the capacitances of the base–emitter junctions

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 discharge, the junctions will begin to open more and more, and the transistors will switch to active mode. In this case, the collector currents of the transistors will increase sharply (sections

3 and

4 in

Figure 3), but the collector–emitter voltage will not change significantly, because the voltage across the load capacitor

CL cannot change quickly. As the capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 are discharged, when the transistor base–emitter voltages change sign, the voltage between the base and the common wire of the first transistor becomes less than

V0, and for the second one is less than 0.5

V0, and the diodes

D1 and

D3 will start to conduct current again. These currents flowing through the resistances

R1 and

R2 will increase the voltage between the base and the common wire, and will prevent the discharge of

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 (transistors will be partially turned off). As a result, equilibrium will be established, and the voltage between the base and the common wire will stop changing. In the steady-state mode, the voltages across the main capacitors

C1 and

C2 and the discharging diode

D5 will remain the same. The base, emitter, and collector currents will also remain the same (sections

5 and

6 in

Figure 3). In this case, the total current to the load

Icom =

IC,1 +

IC,2 will pass through the circuits

V0 →

D2 →

IE,1 →

IC,1 and

V0 →

D1 →

R1 →

D4 →

IE,2 →

IC,2, and will not change significantly due to the weak dependence of the collector current versus the collector–emitter voltage.

As a result, the load voltage will increase according to the following equation

whereas the collector–emitter voltages of the transistors will decrease.

As the voltage across the load increases, the current

through

RL will also increase. When

becomes equal to

Icom, the load voltage reaches the value of

UL,stab =

Icom·

RL and stops changing. It should be noted that if the resistances in the transistor base circuit do not change, the base, emitter, and collector currents also keep their values. As a result, the operating points of the transistors at the dependences

IC,i(

UCE) will remain on the same line when

RL changes, as is shown in

Figure 3, but the values of

R1 and

R2 have to be constant in this case. The operating points

ai,

bi, and

ci, shown in

Figure 3, are calculated at

RL = 100 MΩ, 2 GΩ, and 4.5 GΩ, correspondingly.

When the load voltage increases, the transistor collector–emitter and collector-base voltages will decrease. As a result, saturation mode can occur instead of the active mode, and the collector currents will begin to decrease sharply.

Figure 3 shows that this effect leads to a change in the point

c2 position and to a decrease in the second transistor collector current. In turn, this process also leads to load voltage stabilization. As soon as the load voltage begins to approach the voltage across the capacitor

C2, the collector current of the second transistor will begin to decrease sharply (the collector-base junction of

T2 opens); the total current of the collectors

Icom will also begin to decrease, which slows down and eventually stops the increase in the load voltage.

Figure 4 shows the dependence of the load voltage versus the load resistance measured and calculated at several values of resistances

R1 and

R2 in the transistor base circuits, and

V0 = 10 V.

In order to carry out experimental studies, an experimental setup was designed corresponding to the circuit shown in

Figure 2. The capacitance of capacitors

C1 and

C2 was 1 nF, and for the load capacitor,

CL = 10 nF. Reed relays EDR201A0500 (Excel Cell Electronic, Taichung, Taiwan) were used as the switches. High-voltage diodes 1N4004 (Vishay Intertechnology, Malvern, PA, USA) with a maximum permissible reverse voltage of 400 V and a reverse capacitance of 40 pF at a reverse voltage of 0 V were used as the diodes. The type of bipolar transistors used was BC557A (Fairchild Semiconductor, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Figure 5 shows the photograph of the experimental setup (a) and the block diagram of the setup (b); the numbers indicate the components of the measuring system.

During the experimental study, the dependences of the voltage across the capacitor

CL (

Figure 2) versus the number of conversion cycles at different load resistances were measured. A voltage repeater based on an AD549KHZ (Analog Devices, Wilmington, MA, USA) operational amplifier with an ultra-low input current (0.1 pA) was used to measure the voltage across the capacitor. The primary power supply voltage was varied from 10 to 12.2 V.

The calculation has been carried out under the assumption that when the load resistance increases, the collector currents remain constant, the same as they were at low load resistances. It can be seen from

Figure 4 that the calculation results are in good agreement with the experimental results in the range of low load resistances when the transistors remain in active mode. At the same time, an increase in the resistances

R1 and

R2 in the base circuits shifts the dependences to the range of higher load resistances, because this reduces the currents of the bases, emitters, and collectors.

It follows from the analysis that this circuit (with an unlimited power source) operates as a two-stage voltage divider, where the input voltage division coefficient at high load resistances stops depending on the load resistance and tends to 1/2. At the same time, the load voltage does not change significantly when the load resistance changes and is close to 0.5V0, while the current through the load resistance is close to 0.5V0/RL, i.e., this current decreases when the load resistance increases.

It should be noted, however, that when the divider operates using an ideal constantly connected voltage source V0 with unlimited power, fairly high currents flow through resistors R1 and R2, discharging the source V0 all the time. Therefore, the base currents of the transistors remain low and the transistors remain at the very beginning of the active mode, and, as a result, their collector currents as well as the current through the load RL are also small. Consequently, the efficiency of such a circuit turns out to be low.

4. Analysis of Circuit 2 Operation

In this case, the electric circuit of the system will also correspond to the circuit shown in

Figure 2, where the switches

Sw1 and

Sw2 have to be switched in opposite phases (by turn).

For odd cycles 1, 3, 5 …, when the source

V0 is connected to the divider (

Sw1 is switched on,

Sw2 is switched off), the current and voltage changes in this circuit occur in the same way as shown in the previous section. During these cycles, the charge of the load circuit

RC does not practically occur, and the load capacitor

CL, starting from cycle No. 3 and for further odd cycles, is only discharged through

RL. In this case, the voltage across the load during the

k-th odd cycle will change as

where

is the load voltage at the beginning of the

k-th odd cycle.

When the switch Sw1 is turned off, and the switch Sw2 is turned on (even cycles 2, 4, 6 …), diodes D1, D2, D3, and D4 are reverse-biased, and transistors T1 and T2 are switched on by the discharging current of capacitors C1 and C2 through their base–emitter junctions and limiting resistors R1 and R2. At the same time, the currents of the emitters and collectors of the transistors increase sharply.

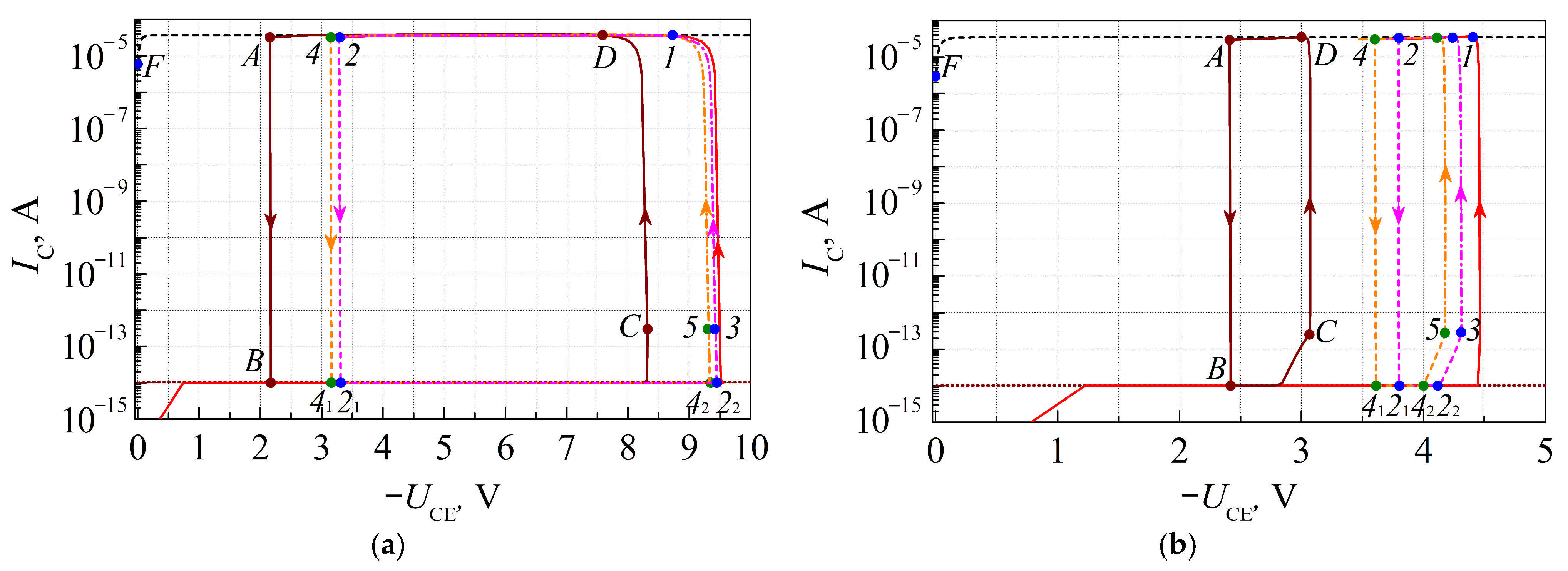

Let us trace the movement of the operating point with coordinates (

IC,

UCE), characterizing the state of the transistors, at the family of output characteristics of

IC(

UCE), shown in

Figure 6. It was assumed in calculations that

C1 =

C2 = 1 nF;

R1 =

R2 = 10 MΩ;

CL = 10 nF;

RL = 50 kΩ;

CBE,1 =

CBE,2 = 2 pF;

CD5 = 40 pF;

V0 = 10 V; and

τ = 2.5·10

−5 s. Here,

τ is the duration of the charge and discharge cycles.

The initial state of the transistors is characterized by the operating point with coordinates (0, 0). When Sw1 is switched on (and Sw2 is switched off), transistors T1 and T2 are switched to the cut-off mode, and the current flows through them; the magnitude of the current is determined by the base potentials of the turned-off transistors.

Upon applying the turn-on signal at the transistor terminals (

Sw1 is off,

Sw2 is on), the operating points will move to positions

1 at the curves with

UBE = const (

Figure 6a,b), since at the first moment, the load capacitor

CL tends to maintain the collector potential constant. Then the capacitor

CL will begin to charge with the time constant

τ1 ≈

CL·

RL.

As the capacitor

CL is charged, the operating points of the transistors

T1 and

T2 will move along the curves with

UBE = const, and if the duration of the even cycle is short enough relative to the time constant

τ1 (in our case,

τ/

τ1 = 0.05), then by the end of the second cycle (the end of the first complete cycle), the operating points will move to positions

2. During this cycle, the expression for estimating the load voltage can be represented as

where

is the voltage across the load resistance at the beginning of the

k-th even cycle and

Icom is the sum of the collector currents of the transistors.

By the end of the second cycle (at the beginning of the third one), the transistors will switch to the cut-off mode, and the operating points will move to position 21. From this moment, the process of the load capacitor discharging begins. In this case, the operating points move towards points 22 and 3. If the duration of the odd cycle (the discharge cycle of the load capacitor) is such that the load capacitor does not have time to fully discharge, then the operating points at the end of this odd cycle will correspond to voltages UCE lower than those at the end of the previous odd cycle.

When the operating points move between

22 and

3, a partial discharge of the base–emitter junction capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 occurs, the junctions will begin to open, and the transistors will switch to the active mode. Position

3 corresponds to the end of the third cycle and to the beginning of the fourth one. The fourth cycle and the second complete cycle will end at point

4. The fifth cycle in

Figure 6a,b will correspond to the movement of the operating points along the trajectory

4 →

41 →

42 →

5. In this case, the time dependence of the load voltage can be represented as

where

F1(

t) and

F2(

t) are defined by Equations (A1)–(A4) (see

Appendix A).

During the derivation of Equation (1), it was taken into account that at the beginning of an even cycle, the transistors

T1 and

T2, which were reverse-biased before the previous odd cycle, do not turn on immediately. It takes some time to discharge the capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2. Moreover,

T2 begins to open only after

T1 has almost completely opened. These delays are taken into account by the parameters

α1 and

α2, and by using the Heaviside step functions Φ(

t −

α1) and Φ(

t −

α2) (see

Appendix A).

After several cycles of operation, a steady-state mode occurs for which the operating points of the transistors will move along the loop

A →

B →

C →

D. In this case, the maximum and minimum output voltages stabilize, and in the steady-state mode, can be evaluated using the following equations:

where

β is the transistor amplification factor and

F3 and

F4 are determined using Equations (A5) and (A6) (see

Appendix A).

The equations obtained show that after reaching the steady-state mode with the periodic connection of the voltage source

V0, the load voltage during the cycle, unlike in the previous circuit (

circuit 1), does not remain constant, but pulsates. In this case, the range of the load voltage fluctuations is equal to

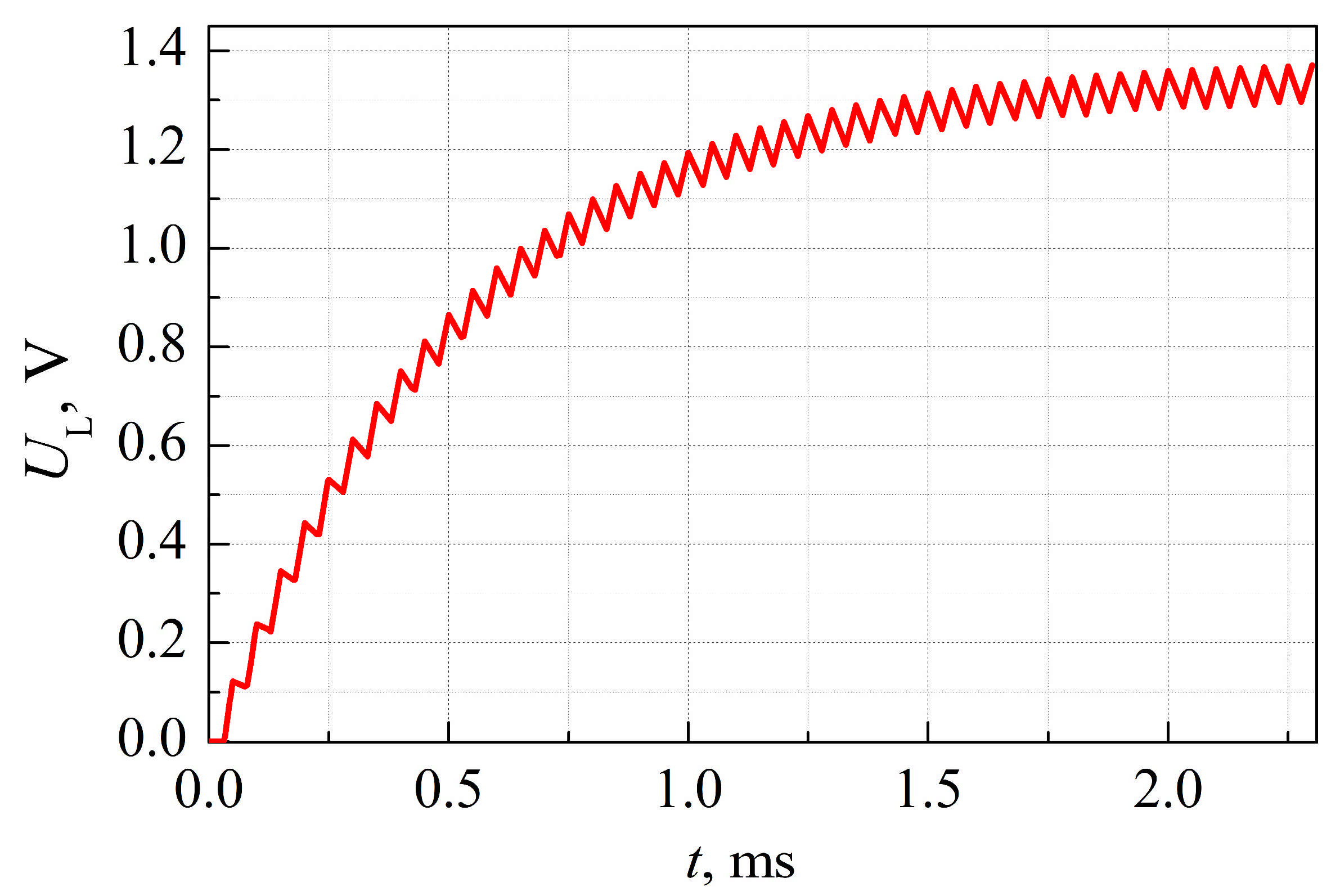

Figure 7 shows the time dependence of the load voltage calculated at the same parameters as the dependences shown in

Figure 6. One can see that the voltage ripples at the load resistance

RL = 50 kΩ remain in the steady-state mode too. According to Equation (2), as the load time constant

CLRL increases, the ripple range decreases.

It should be noted that the considered mode of operation of this circuit is very sensitive to the parameters of the elements used. The variation in the limiting resistances, reverse capacitances of the diodes, and the parameters of the transistors within relatively narrow ranges can significantly change the mode of the divider operation from the near-complete transistor cut-off to the transistor saturation mode. In addition, the studied mode is realized only with a sufficiently short cycle duration. For instance, for the above-presented calculations, the complete cycle duration was 50 μs, i.e., the switching frequency was 20 kHz. At the same time, since for this circuit, the source V0 is periodically disconnected from the divider, and during these cycles it is not discharged through the limiting resistors R1 and R2, the efficiency of this circuit turns out to be significantly higher than that of the previous circuit, and can reach up to 20%.

The high switching frequency significantly narrows the scope of application of such a divider in this mode, especially if it is designed for operation as part of low-power EMGs with low output voltage. The range of mechanical vibrations available in the environment is usually limited to frequencies of a few hundred Hz.

When the switching frequency decreases (the cycle duration increases), the load capacitor can have enough time to charge significantly. In this case, after several switching cycles, the operating point during the even cycles (

Figure 6, points

F) can significantly shift towards the ordinate axis, and the transistors will switch from active mode to saturation mode. In this case, the collector currents (charging the load) will first begin to decrease, and then they can even change direction, which, in general, will lead to a decrease in the load current and, eventually, to stabilization of the output voltage. The saturation mode is achieved faster by increasing the input voltage, reducing the limiting resistances, and increasing the load resistance. Before the collector currents begin to decrease (at the initial cycles), the operation of the circuit will proceed as described earlier.

It should be noted that even with the periodic connection of the source

V0 for

circuit 2 (

Figure 2), the switch

Sw2 can be excluded. Let us call such a circuit

circuit 2m. In the presence of

Sw2 (

circuit 2), during the even cycles (when this switch is on), the diodes

D1 and

D2 are reverse-biased. However, during the even cycles and without

Sw2 (

circuit 2m), when the source

V0 is disconnected from the divider, the diodes

D1 and

D2 are connected towards each other, and one of them will always be reverse-biased, so the current through these diodes will be small in this case too. However, using the switch

Sw2 in the previous analysis of

circuit 2 simplified the analytical calculations, but for the implementation of

circuit 2, it is required to have the control circuit of the switch

Sw2, resulting in additional energy consumption in contrast to

circuit 2m. Furthermore, we will analyze

circuit 2m (

Figure 2), assuming that

Sw2 is turned off all the time.

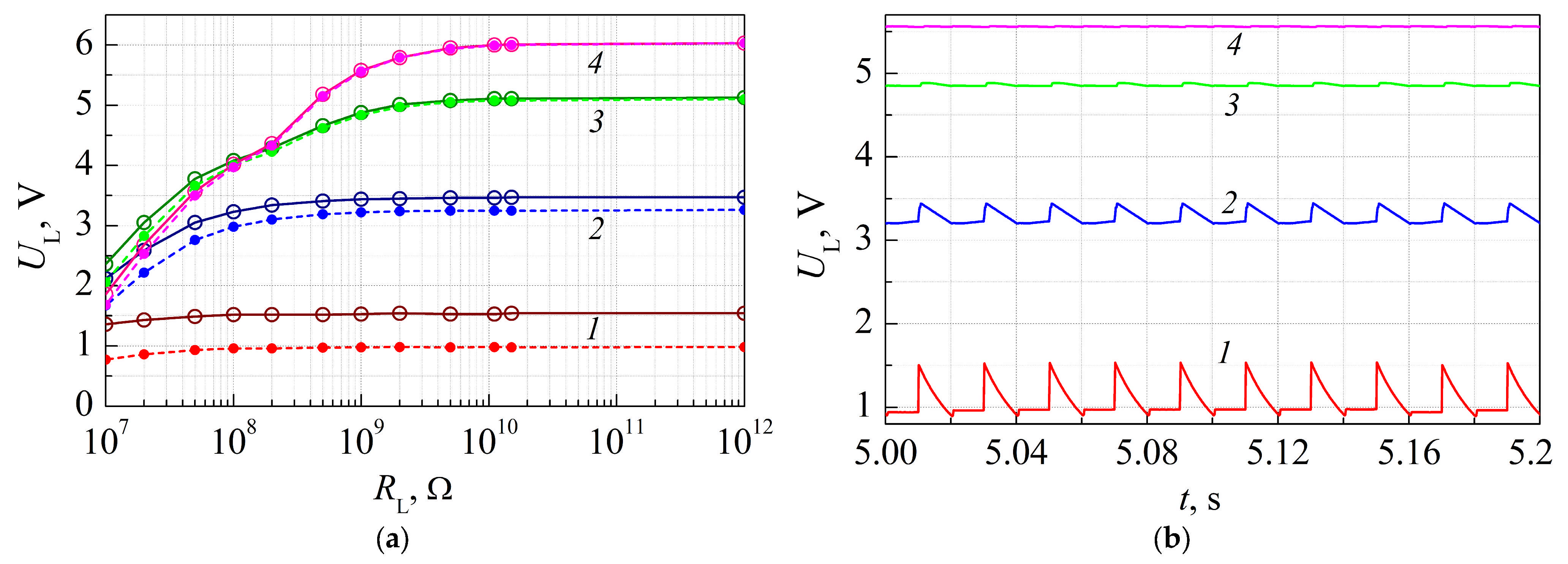

Figure 8a shows the dependences of the maximum (solid lines) and minimum (dashed lines) load voltages for

circuit 2m versus the load resistance measured at several limiting resistance values, and

V0 = 10 V,

τ = 10 ms.

It can be seen from

Figure 8a that as the load resistance increases, the voltage across the load stops increasing, reaching saturation. When the resistance of the limiting resistors increases, the saturation voltage also increases. Thus, the input voltage division coefficient

K =

UL/

V0 increases with increasing limiting resistances, and only at

R1 =

R2 = 80 MΩ and

RL > 1 GΩ the division coefficient

K ≈ 0.5, which corresponds to the expected value for the two-stage voltage divider, when the divider is periodically connected to an electrical energy source with unlimited power.

Thus, during the design of such a divider for operation as part of EMGs with a low output voltage, it is necessary to carry out appropriate preliminary estimations, and not just assume that the number of the divider stages N guarantees the division coefficient K = 1/N.

Figure 8b shows the time dependences of the load voltage measured at

RL = 1 GΩ for different values of

R1 and

R2. It is obvious from

Figure 8 that as the values of the limiting resistors

R1 and

R2, and the load resistance

RL, increase, the output voltage ripple (the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the load voltage) decreases and becomes almost unnoticeable when

RL > 800 MΩ and

R1 =

R2 ≥ 80 MΩ.

Figure 9 shows the dependences of the maximum (a) and minimum (b) voltages across the divider load for

circuit 2m versus the load resistance measured and calculated when the divider is periodically connected to the electric power source with unlimited power; the data are presented for several values of the limiting resistances. It is evident that the experiment and the calculations, using the made assumptions, agree well. Thus, it can be assumed that such calculations adequately describe the operation of this divider, and they can be used at the preliminary design stage to find the necessary parameters of the circuit elements.

5. Analysis of Circuit 3 Operation

In order to analyze the operation of the two-stage voltage divider with a primary energy source with limited power (

circuit 3), we will use the circuit shown in

Figure 10.

For this circuit, the switches

Sw1 and

Sw2 also operate in the opposite phase. During the time intervals when the switch

Sw1 is turned on, the switch

Sw2 is turned off (even cycles). In this case, the capacitor

C0 is charged from the ideal voltage source up to the voltage

V0. Then the switch

Sw1 is turned off, whereas the switch

Sw2 is turned on (odd cycles), and the charged capacitor

C0 is connected to the divider and gives it part of its charge. As a result, during the charging process of the divider, the voltage of its power supply (now it is

C0) will not remain constant. In addition, the voltage which is reached by the divider during the charging phase (odd cycles) will now also depend on the residual charge on the divider (the charge remaining on the divider at the end of its discharging phase to the load during the even cycles). Calculations show that when the divider is connected to the voltage source with limited power (odd cycles), the voltage across the capacitor

C0 will change according to the law

where

and

are the voltages across the capacitors

C1 and

C2 at the end of the even cycle and

and

are the voltages across the diodes

D1 and

D3 at the end of the even cycle before

C0 is connected to the divider. In the derivation of Equation (3), it is taken into account that when the divider is connected (

Sw1 is switched off,

Sw2 is switched on), the capacitor

C0 is at the first moment partly discharged almost instantly to the in-series-connected capacitors

C1 and

C2, and only then does it continue to discharge through the in-series-connected limiting resistors

R1 and

R2.

The main difference between circuit 3 and the above-discussed circuit 2m, where the voltage source V0 was stable, is in the instability of the power supply voltage (C0 voltage).

The process of the divider discharging to the load (when Sw2 is turned off, in even cycles) in this circuit will occur similarly to circuit 2m. It should be noted that, also in this case, at the beginning of the even cycle, the transistors that were turned off during the previous odd cycle do not turn on immediately. It takes some time to discharge the capacitances CBE,1 and CBE,2, and this fact was taken into account in deriving Equation (1).

Figure 11 shows the time dependences of the load voltage calculated for

circuit 2m and

circuit 3, with two values of the load capacitor

CL = 1 nF and 10 nF, resistances

R1 =

R2 = 200 MΩ, and

RL = 10 MΩ. The odd cycle corresponds to the time from 0 to 0.01 s, and the even cycle, from 0.01 to 0.02 s.

During the even cycle, the delay of the voltage growth across the load due to the discharge of the capacitances CBE,1 and CBE,2 for the first transistor is about 1.5 ms, and for the second one is about 3.5 ms. As the load capacitance CL decreases, the voltage oscillations range increases, and the discharge of CBE,1 and CBE,2 becomes more pronounced.

It is obvious from

Figure 11 that for the same circuit elements, the maximum value of the load voltage for

circuit 2m is greater than that for

circuit 3. This effect is more evident for values of the limiting resistors

R1 and

R2 in the range from 10 MΩ to 200 MΩ, and the load resistance

RL in the range from 10 MΩ to 100 MΩ. For lower resistances, the currents through the circuits become so high, and the discharge time of the capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 is so short, that the delay becomes barely noticeable and only one (common) extremum appears. At higher resistances in steady-state mode, the voltage across the load changes weakly, and the charge on the capacitances

CBE,1 and

CBE,2 almost does not change as well. The appearance of two extrema (

Figure 11) during the even cycles changes the spectral composition of the output voltage, which must be taken into account during subsequent filtration design.

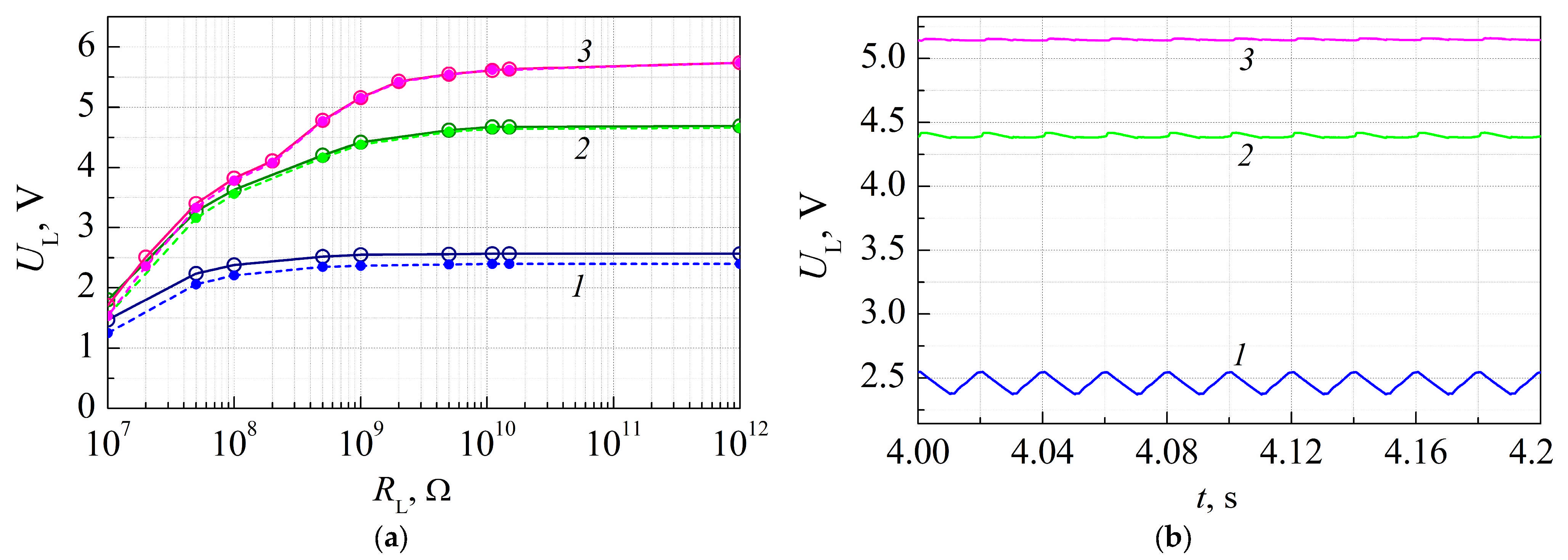

Figure 12a shows the experimental dependences of the maximum

UL,max and minimum

UL,min load voltages versus the load resistance for

circuit 3 measured at

C0 = 1 nF,

R1 =

R2 = 10 MΩ, 80 MΩ, and 200 MΩ. In general, these dependences are similar to the corresponding dependences for

circuit 2m, shown in

Figure 8a, but they are located a bit lower. As the load resistance increases, the dependences of the maximum and minimum voltages across the load for

circuit 3 also reach the saturation level. The value of the saturation voltage depends on the resistances

R1 and

R2 in the transistor base circuit, and when the resistance of the limiting resistors increases, the saturation voltage increases too.

Figure 12b shows the time dependences of the load voltage measured at

RL = 1 GΩ and

R1 =

R2 = 10 MΩ, 80 MΩ, and 200 MΩ for

circuit 3. It is obvious from

Figure 12 that as the values of the limiting resistors

R1 and

R2 and the load resistance

RL increase, the output voltage ripple decreases.

Figure 13 shows the dependence of the ratio between the maximal load voltages for the circuits with periodic connection of

C0 (

circuit 3) and

V0 (

circuit 2m) versus the load resistance measured at

R1 =

R2 = 10 MΩ, 80 MΩ, and 200 MΩ. It is obvious from

Figure 13 that as the resistances in the transistor’s base circuit decrease, the difference between the maximal voltages for circuits

2m and

3 increases, and can reach 30%. This is because (for

circuit 3) the decrease in the limiting resistances leads to an increase in discharge in the capacitor

C0, which directly affects the voltage across it according to Equation (3), while for

circuit 2m, the voltage applied to the divider does not change and remains equal to

V0.

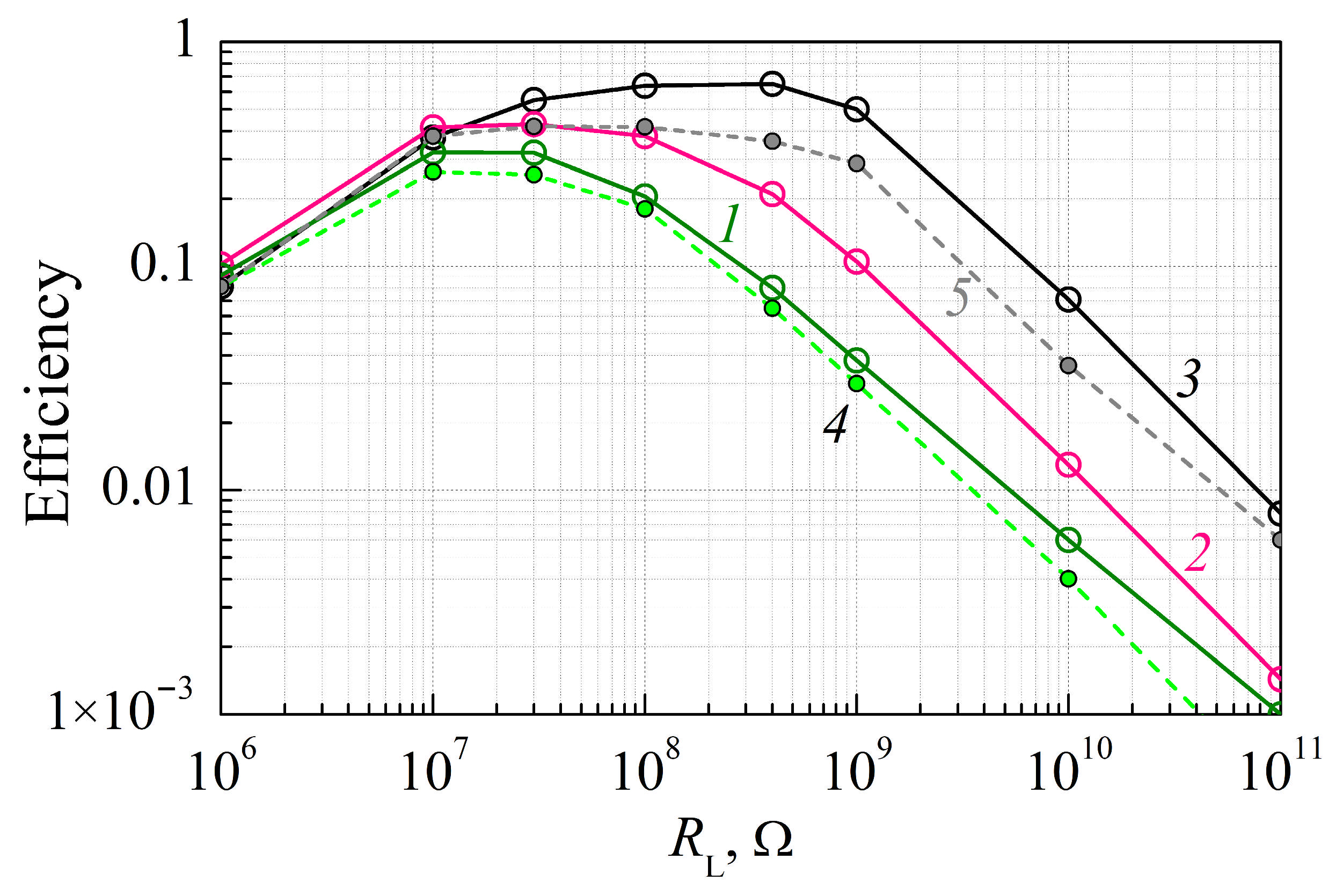

The limited power of the primary voltage source also affects the divider efficiency.

Figure 14 shows the dependence of the ratio between the average energy transfer rate to the load (output power) per cycle, and the average energy extraction rate from the primary source

V0 or

C0 per cycle, calculated using experimental data for

circuit 2m (solid lines) and

circuit 3 (dashed lines), respectively.

It can be seen from

Figure 14 that the efficiency can reach 60% for

circuit 2m and 40% for

circuit 3. Thus,

circuit 3 performs the conversion less efficiently than

circuit 2m. Also, as the resistance of the limiting resistors increases, the efficiency increases for both circuits. This is due to the decrease in the current through these resistors during the odd cycles.

Moreover, an increase in the limiting resistances

R1 and

R2 leads to an increase in the load resistances

RL, for which the division coefficient of the divider stops changing (

Figure 8 and

Figure 12).

The analysis shows that it is possible to reduce the effect of the power supply discharge by reducing the odd cycles duration, keeping the complete cycle duration unchanged. Calculations show that for the complete cycle duration of 0.02 s, the reduction in the odd cycles duration from 0.01 s to 0.002 s can increase the efficiency by 5%, and to 0.001 s, by 8%.

Thus, in the process of the voltage divider design, it is necessary to simultaneously take into account the dependence of the load voltage on the load resistance, the dependence of the efficiency on the load and limiting resistances, as well as the dependence of the efficiency on the cycle duration.

In order to verify the adequacy of the developed concepts regarding the operation of the divider circuits with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors, an analysis of the three-stage voltage divider operation was carried out. The electrical circuit of such a divider corresponds to the circuit shown in

Figure 1, but with the voltage source (

C0) with limited power, similar to that shown in

Figure 10.

Within the framework of the developed theory about the operation of the divider circuits with transistor–diode commutation, the following analytical expressions were obtained for the three-stage voltage divider in order to calculate the dependence of the load voltage versus the resistances of the limiting and the load resistors:

where

and

are the maximal load voltages for high and low resistances, respectively,

is the minimal load voltage,

C is the charge accumulated in the transistor base during the saturation mode,

VD is the voltage drop across the opened (forward-biased) diode, and the values of

F*,

C1,L,

CL,1,

CD,1,

Csum,

Ceq,

R1,L,

Kq,

Kτ,ch,

Kdis,1,

Kdis,2,

Kdis,3,

Kdis are defined by Equations (A7)–(A19) (see

Appendix B). The values

UBE = −0.51 V and

UCE = −0.015 V are the voltages of the transistor base–emitter and collector–emitter junctions during the saturation mode and Δ

τch and Δ

τdis are the durations of the charge (odd cycle) and discharge (even cycle) cycles of the divider.

Similarly to the case of the diode-switching divider [

32,

33], in this case, it is not possible to obtain one general equation for

VL,max at an arbitrary load resistance. This is because at high load resistances, the discharging diodes

VD3,1 and

VD3,2 (

Figure 1) remain reverse-biased throughout the conversion cycle. The voltage across the capacitances of the reverse-biased discharging diodes does not change sign and the entire cycle adds to the voltage across the capacitors

C1 and

C2. However, at low load resistances, when a significant charge is taken from the divider during connection to the load, the capacitances of the discharging diodes have more time to discharge, the voltage across the discharging diodes changes sign, and it is then subtracted from the voltages across the capacitors

C1 and

C2. In the first case, the maximum voltage across the load asymptotically approaches the sum, while in the second case, it approaches the difference between the voltages across the capacitors

C1 and

C2 and the forward-biased discharging diodes

VD3,1 and

VD3,2. The transition from Equation (6) to Equation (4) takes place at

, for which

.

It should be noted that because in circuits with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors the stabilization effect (transition of transistors to saturation mode) is much stronger than in circuits with diode commutation of switchable capacitors, the excess of VL,max over the value of V0/N is significantly less.

Figure 15 shows the dependences of the maximum and minimum load voltages versus the load resistance during the periodical connection of the capacitor

C0 to the three-stage voltage divider measured and calculated using Equations (4)–(6) at

V0 = 10 V,

R1 =

R2 =

R3 = 80 MΩ,

C1 =

C2 =

C3 =

CL = 1 nF, for diodes 1N4149 with the reverse capacitance of 5 pF for different values of

C0, Δ

τch, and Δ

τdis.

One can see from

Figure 15 that the maximum values (curves

1) of the load voltage at

C0 = 4.7 nF are higher than the corresponding voltages at

C0 = 1 nF, especially at low resistances.

The decrease in the maximum voltage across the load resistance, when the capacitance C0 is decreased, for circuit 3, is due to the fact that when the capacitor C0 (initially charged up to V0) is connected to the divider, the voltage across C0 does not remain constant, but it decreases.

At the same time, the voltage, which the divider reaches during the charging phase (odd cycles), will also depend on the residual charge on the divider. This residual charge remains on the divider (on the discharging capacitors) at the end of the discharging phase of the divider to the load (even cycles). This can be seen from

Figure 1b, where instead of the unlimited power source

V0, the limited power source

C0 should be connected.

Since the total charge in the system does not change during the transfer of a part of the charge from

C0 to the divider (odd cycles), assuming

C1 =

C2 =

C3, we have

where

N is the number of the divider charged capacitors (the number of the divider stages) and

Vres is the residual voltage on each of the capacitors

C1,

C2, and

C3 at the end of the previous (even) cycle. It follows that, in an ideal case, during the charging phase, the voltage across

N series-connected capacitors

C1,

C2, and

C3 will be equal to

At low load resistances, when the load capacitor is rapidly discharged, and the voltages across the load and

Vres decrease, the value of

Vch also decreases. If

Vres drops to zero, then

Thus, it can be found that with a decrease of

C0, the voltage (and charge) across each of the capacitors

C1,

C2, and

C3 decreases. As a result, during the subsequent even cycle, when the divider is connected to the load (

Figure 1c), a smaller charge is transferred to the load and the maximum voltage across the load is also reduced:

It has been taken into account here that during the odd cycle, an additional discharge of C0 occurs through the limiting resistors.

Our analysis has revealed that within the framework of the developed concepts regarding the operation features of the voltage divider with transistor–diode commutation of switchable capacitors, the calculation results are in good agreement with the experimental data for a wide range of circuit parameters.