A New and Smart Gas Meter with Blockchain Validation for Distributed Management of Energy Tokens

Abstract

1. Introduction

- •

- The measuring system, together with pressure and temperature transmitters to convert the gas volume to reference conditions. All measured variables are communicated to the Central Processing Unit (CPU) via a digital signal.

- •

- A Central Processing Unit (CPU) that processes, records, and prepares the data for transmission to the Central Data Acquisition System via a dedicated communication protocol.

- •

- A communication device required to transmit the measured parameters to the Central Data Acquisition System.

- •

- A remote-controlled valve, required to remotely shut off the gas supply in the event of anomalous data (possible leaks) in residential applications.

- •

- Power supply, since electronic components are used. For safety reasons, battery power should be used.

- •

- The absence of moving parts that make this kind of device not subject to wear and tear, allowing it to operate in a wide variety of environmental conditions with minimal maintenance;

- •

- The compact size that makes them suitable for installation in confined spaces;

- •

- A direct electrical output that does not require special devices for remote readings, significantly reducing data collection times;

- •

- Good accuracy;

- •

- Capability to detect reverse flow;

- •

2. Materials and Methods

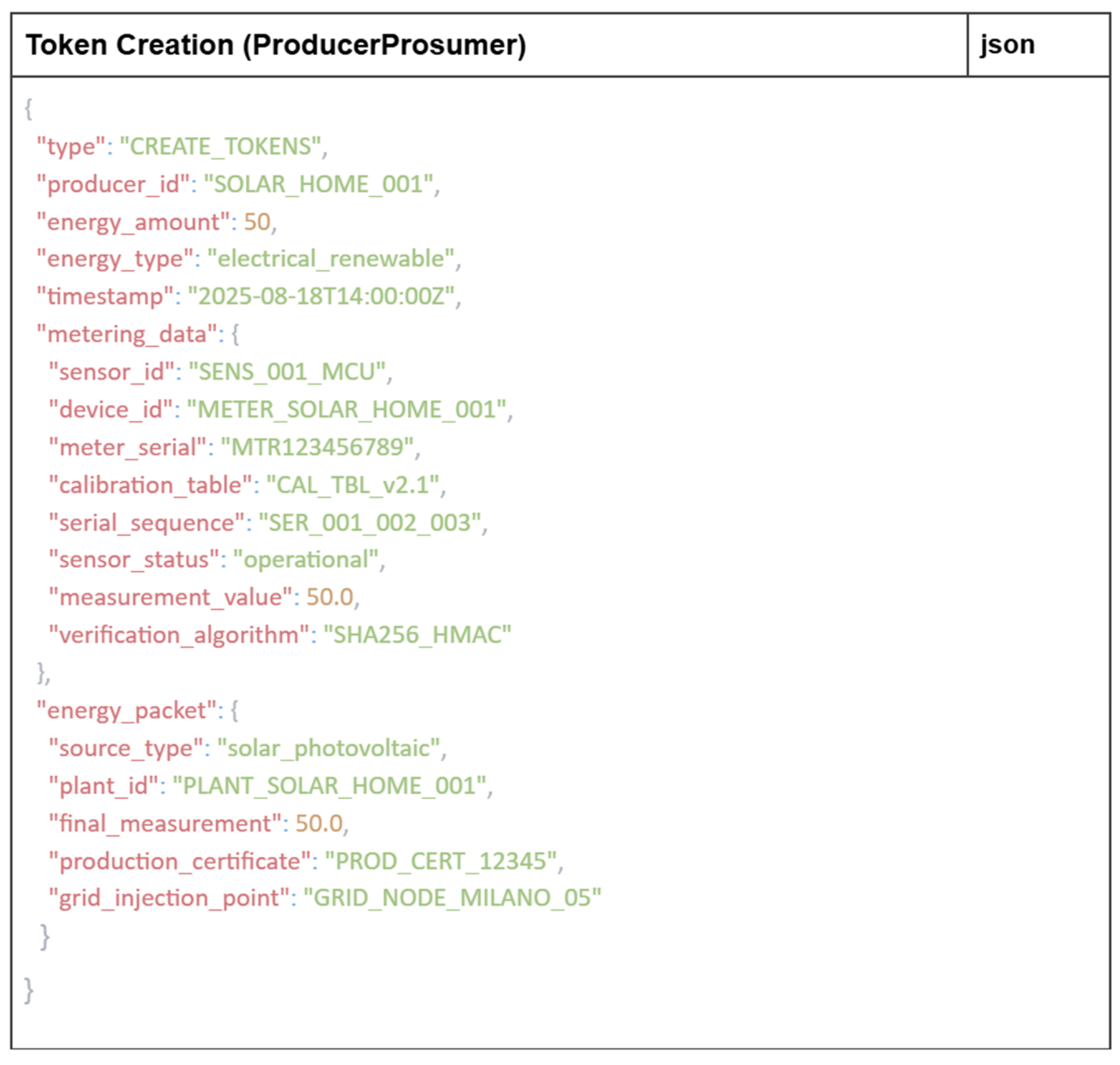

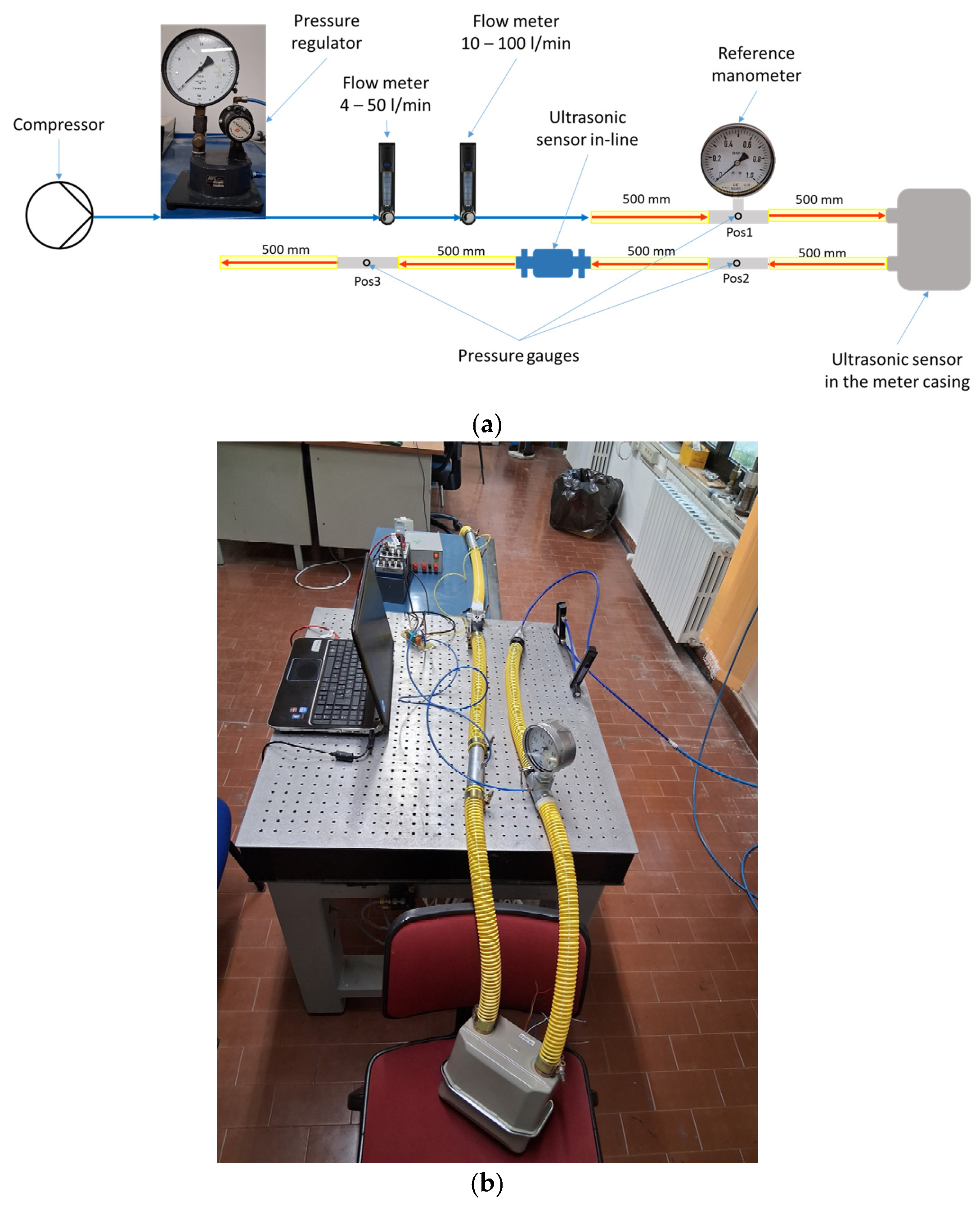

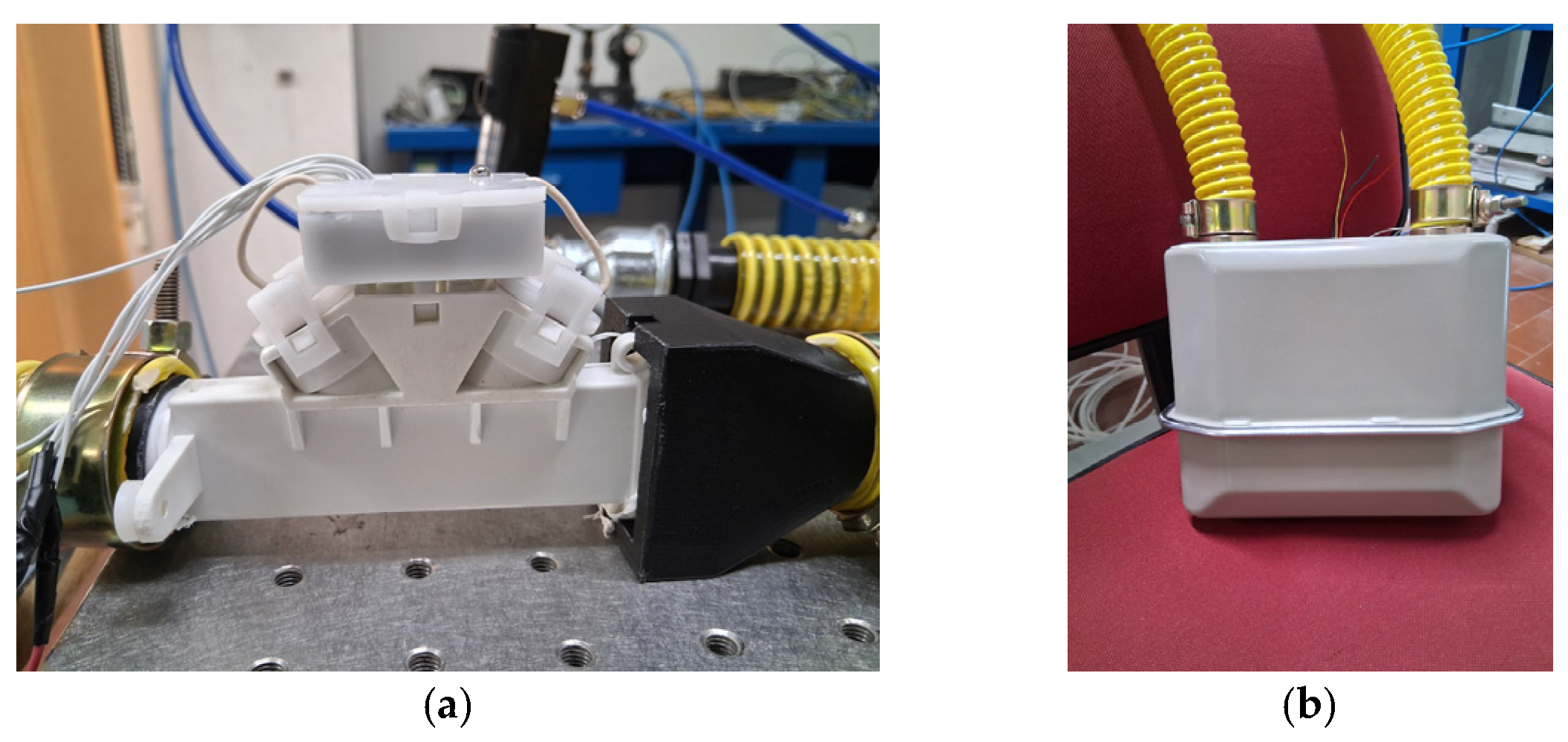

2.1. Flow Measurement Validation

2.2. LoRa-NB IoT Structure

- •

- NB-IoT coverage is limited, so data is sent through LoRa to the nearest covered point;

- •

- When many gas meters of this type are installed in a neighborhood.

2.3. Data Security and Transparency

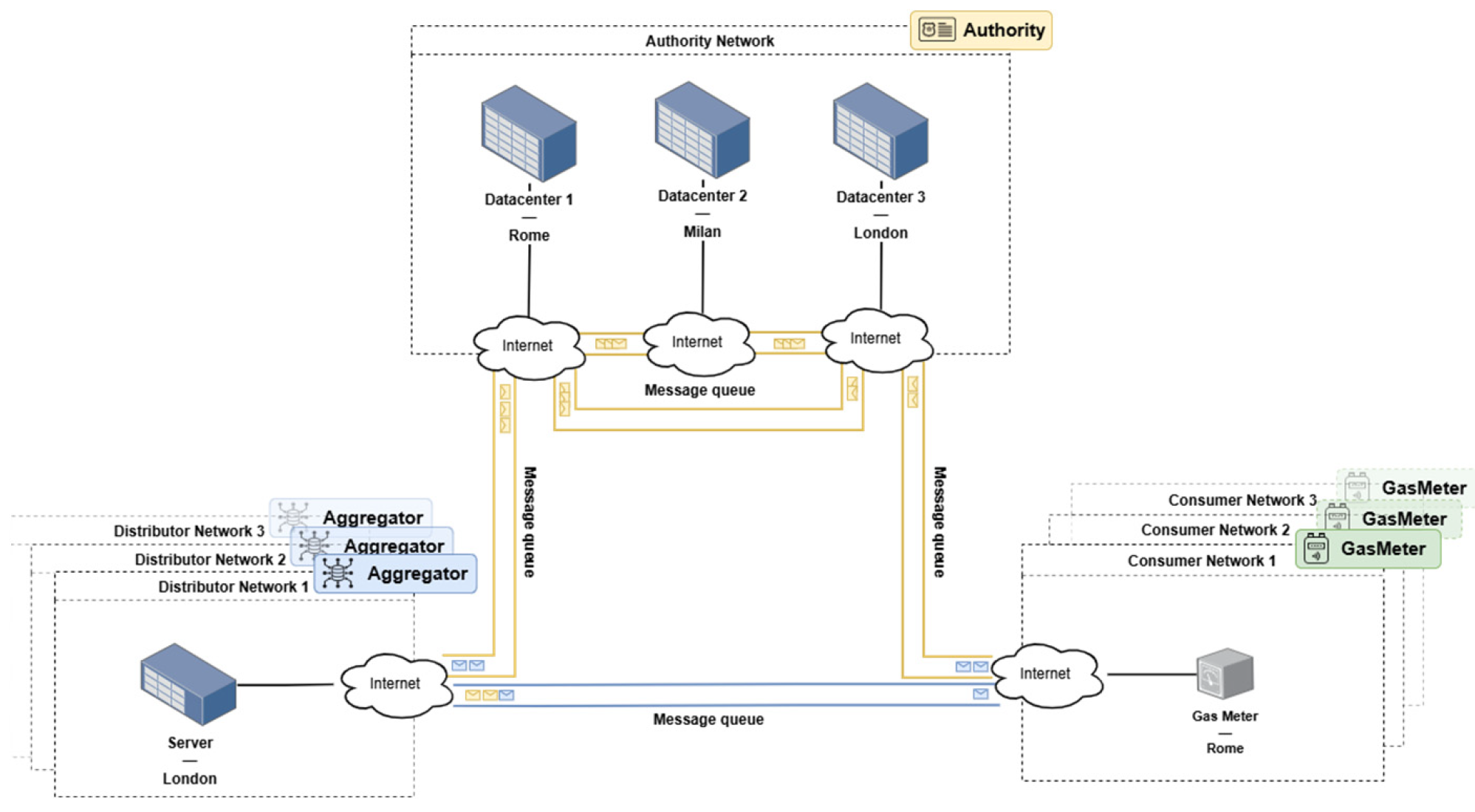

2.3.1. The Proposed Infrastructure

- •

- Authority nodes, responsible for system validation and supervision;

- •

- Aggregating nodes, for acquisition, processing and transmission of data originating from edge nodes;

- •

- Edge/gas meter nodes, corresponding to the in situ devices performing local measurements.

- •

- Network Type: Private permissioned (Hyperledger Besu with Proof of Authority consensus algorithm);

- •

- Mechanism: Proof of Authority (PoA) with pre-authorized validators;

- •

- Network ID: 1337 (custom private network identifier);

- •

- Block Time: ~5 s in test configuration;

- •

- Block Gas Limit: 8,000,000 gas units;

- •

- Theoretical Capacity: ~4–5 batches per block (with optimal batches of 50 tx), equivalent to ~200–250 energy transactions per block.

- •

- Only consumer: the domestic gas meters in basic configuration;

- •

- Only producer: for meters installed at production sites;

- •

- Prosumer: domestic sites with hybrid characteristics (local production and use of energy).

| # | Communication Path | Interval/Frequency | Payload Size (Bytes) | Average Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edge → Aggregator | Consumer (60 s) | 775–835 | 50–150 ms |

| 2 | Aggregator → Authority | Batch interval (30 s) | 30,750–41,750 (batch of 50 tx) | 800–1200 ms |

| 3 | Authority ↔ Authority | Continuous during block cycle (~5 s) | 2000–5000 | <5 ms (LAN) |

| 4 | Authority → Aggregator | On block confirmation (~5 s) | 256–512 | 10–50 ms |

| 5 | Aggregator → Edge | On tx confirmation (~6–37 s after submission) | 180–250 | 50–150 ms |

2.3.2. Simulation of the Infrastructure

- •

- A 64 GB RAM capacity;

- •

- Two CPUs and 12 cores, with nested virtualization enabled;

- •

- Many Ethernet interfaces for configuration and simulation flexibility purposes.

- Transaction Generation Frequency:

- •

- Consumer node: 1 transaction every 60 s (average consumption 2–8 kWh);

- •

- Producer node: 1 transaction every 45 s (average production 5–15 kWh);

- •

- Prosumer node: 1 transaction every 90 s (production/consumption/transfer mix).

- MQTT Broker Load (Aggregator):

- •

- Concurrent Connections: Tested from 3 edge devices (PoC) up to 500 simultaneous connections in stress tests;

- •

- Message Throughput: 100–200 msg/s in stress test scenarios;

- •

- QoS Used: QoS 1 (at least once) to ensure reliable delivery of critical energy transactions;

- •

- Keep-alive: 60 s;

- •

- Average Payload Size: 775–835 bytes (JSON signed with Ed25519).

- Batch Configuration and Throughput:

- •

- Batch Interval: 30 s (configurable via BATCH_INTERVAL_SECONDS in the 10–120 s range);

- •

- Batch Size: Min 1 tx, max 50 tx (adaptive based on network load);

- •

- Theoretical Blockchain Throughput: ~240 transactions/minute with optimal batches (48 tx/batch × 5 blocks/min);

- •

- Observed Blockchain Throughput: ~100 transactions/minute in nominal test scenarios.

- •

- Edge → Aggregator (MQTT): 50–150 ms (dependent on simulated network latency);

- •

- Batch processing: 200–500 ms (a function of batch size and Merkle tree construction);

- •

- Smart contract execution: 800–1200 ms (dependent on gas used and batch complexity);

- •

- Block confirmation: ~5 s (PoA block time);

- •

- Total End-to-End Latency: 6–37 s (average 20 s).

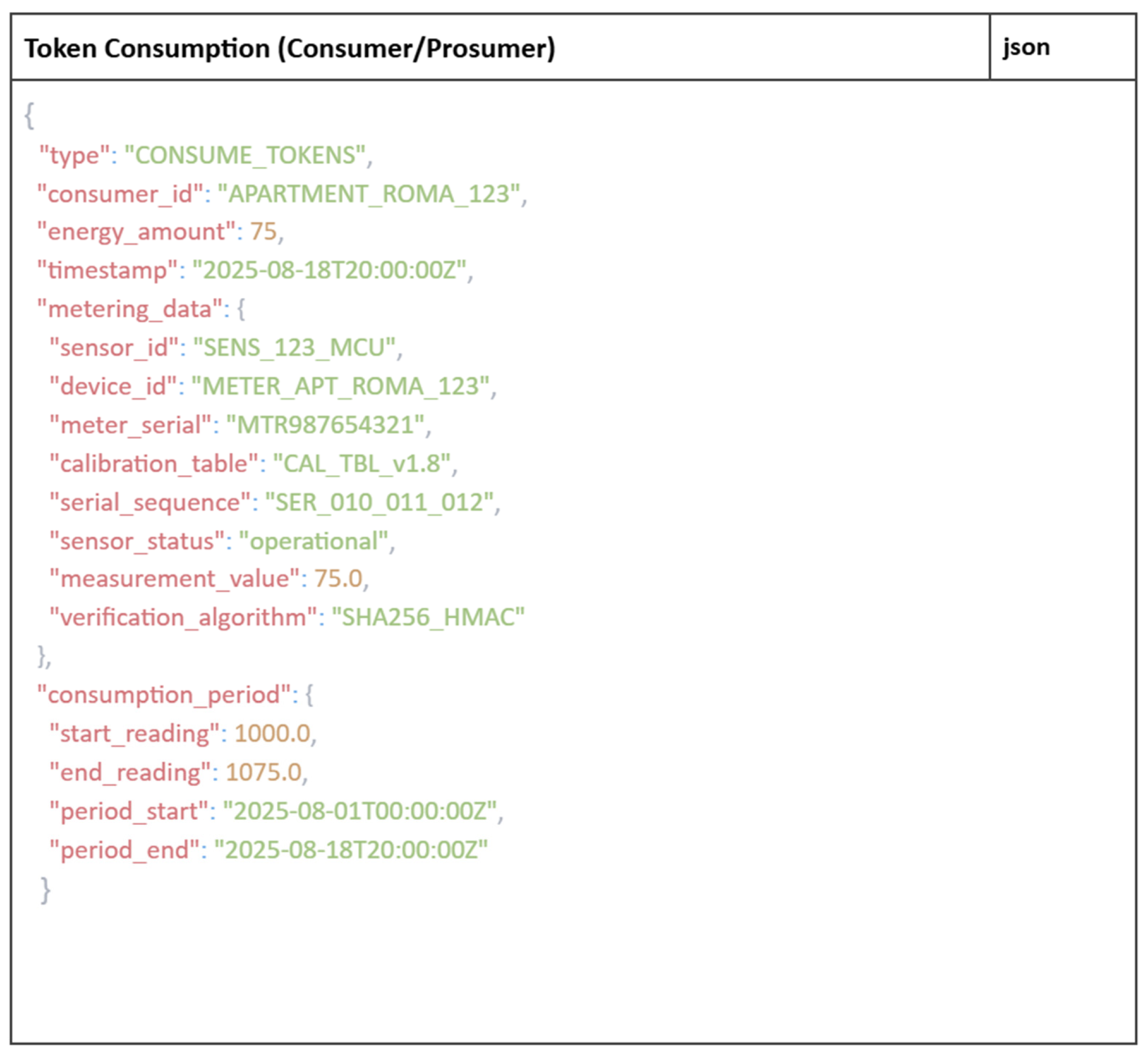

2.3.3. Data Management

- •

- Metering package (gas meter):

- Data concerning the measuring sensor;

- ID sensor (microcontroller);

- ID measurement device (and reference to the calibration);

- Serial number of metering device;

- Calibration data.

- •

- Data of the Meter:

- ID meter (serial number);

- Pool/set data for meter configuration;

- Timestamp.

- •

- Data of the Firmware Measurement block:

- Pool/set of progressive pre-charged serial numbers;

- Sensor status;

- Measurement value;

- Algorithm parameters concerning acknowledgement serial reception.

- •

- Energy data:

- ID production plant;

- Production certificate;

- Site of production;

- Energy source type (solar, hydroelectric, etc.);

- Energy measurement data;

- Measurement unit (kWh, m3, etc.).

- •

- Preamble: a fixed value representing the beginning of the string, without an associate value;

- •

- Corp: the data to be sent in this string;

- •

- CRC: standard control for data integrity check;

- •

- Termination characters: characters indicating the end of the segment.Table 3 describes the payload string structure.

| Segment | Data Type | Identifier | Bytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Data concerning the measuring sensor | Preamble | AA01 | 4 |

| 1—Data concerning the measuring sensor | ID Sensor | IDM01 | 10 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 1—Data concerning the measuring sensor | CRC | CRC | 4 |

| 1—Data concerning the measuring sensor | Escape Sequence | \n\r | 2 |

| 2—Data of the meter | Preamble | AA02 | 4 |

| 2—Data of the meter | ID Meter | IDM02 | 10 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 2—Data of the meter | Escape Sequence | \n\r | 2 |

| 3—Data of the firmware measurement block | Preamble | AA03 | 4 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 3—Data of the firmware measurement block | Escape Sequence | \n\r | 2 |

| 4—Energy data | Preamble | AA04 | 4 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 4—Energy data | Escape Sequence | \n\r | 2 |

| //END | //END | //END | //END |

2.3.4. Blockchain System Authentication

- •

- The company, which is a sensor producer, asks to be qualified, based on an audit of the Certification Authority.

- •

- After qualification, the company obtains a set of cryptographic keys and proprietary algorithms (for each sensor and/or measurement system) to generate a pool of serial codes to be pre-charged into the firmware.

- •

- The generation algorithm will block the serial codes during the installation phase into the firmware; they will be needed for authentication of each measurement datum to be transmitted. In fact, their function is to univocally individuate the authorized single device. Furthermore, these codes will be used to preserve the sequence of transactions; this way, each transaction could be recovered in the case of transmission problems.

- •

- Network validation during each communication: The message payload also includes one pre-charged code to be validated by challenge–response techniques and cryptographic ones based on public/private keys; only after this step will the blockchain consider this communication authenticated.

2.3.5. Communication Protocol

- •

- Communication between nodes:

- Authority ↔ Data logger: MQTT with dedicated topics for sending batch and reception block confirmation;

- Data logger ↔ Data logger: MQTT with publish–subscribe function for synchronization of the local status;

- Authority ↔ Authority: MQTT with private topic for consensus communications.

- •

- Communication between Gas meter and Server:

- Protocol: MQTT over TLS to improve the energy efficiency at the edge devices;

- Topic Structure: Different topics between transactions and heartbeats;

- Local buffer: Transaction queue in the case of temporary disconnection with automatic retry.

- •

- Communication between Distributor and Server:

- Protocol: MQTT for architectural compliance;

- Batch Processing: Topic for sending aggregate;

- Real-time Alerts: MQTT retains messages for immediate notification of critical events.

3. Results

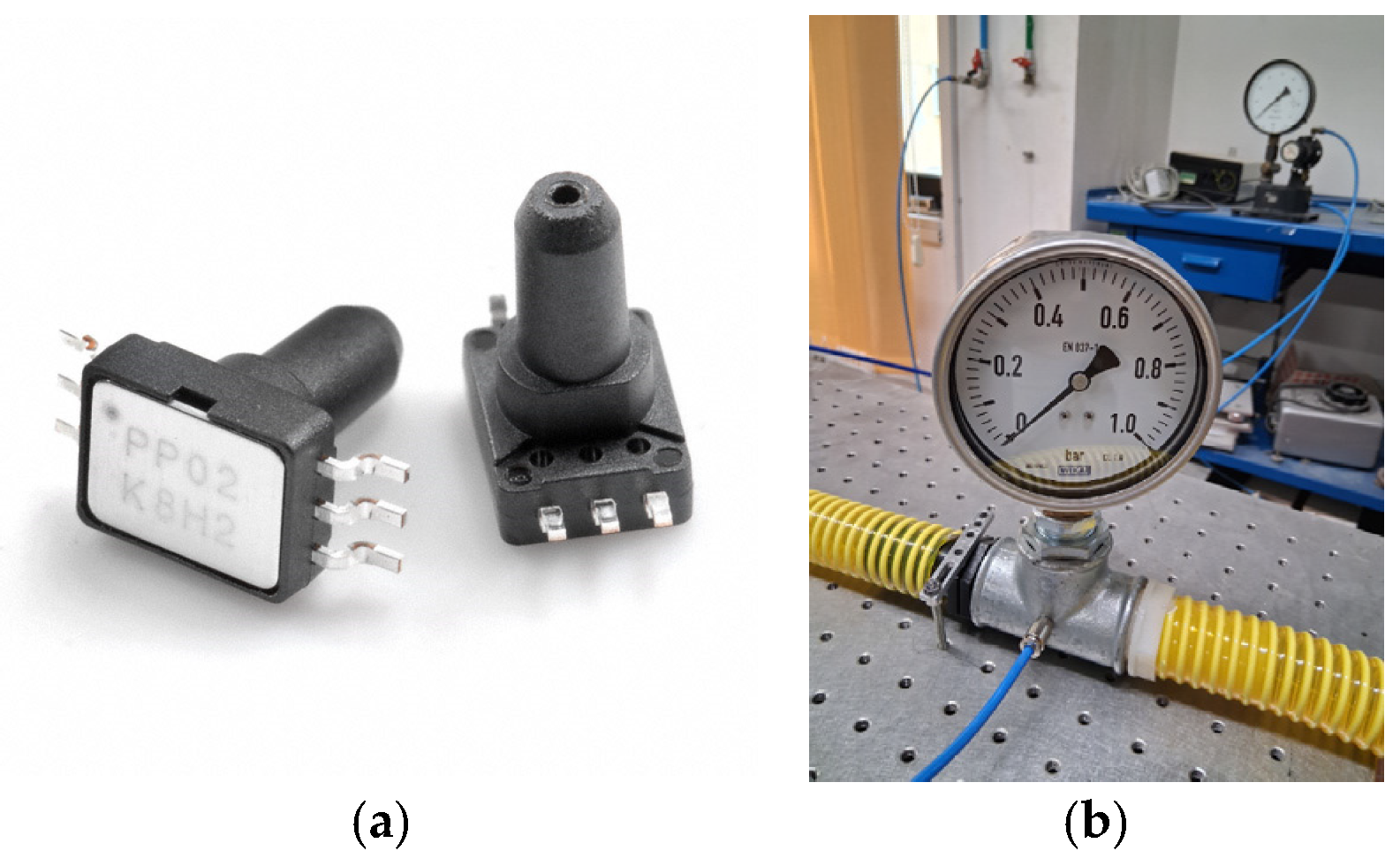

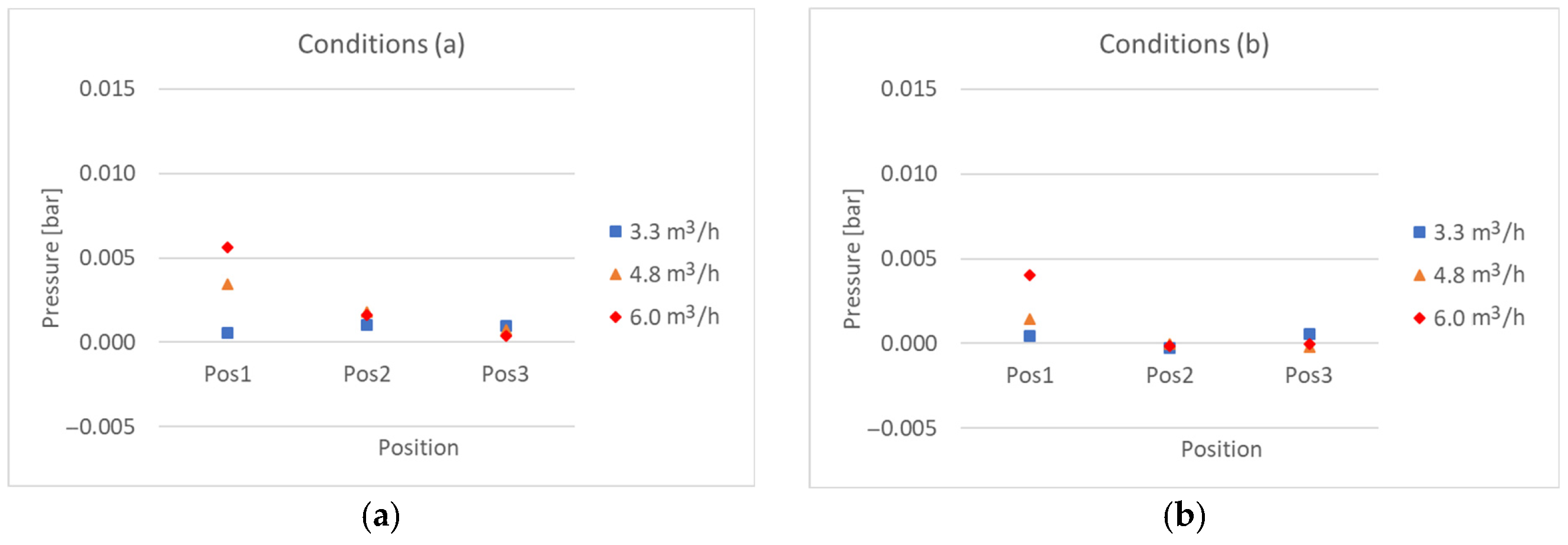

3.1. Metering Validation

- •

- For the fluid dynamic aspects, validation of the pressure behavior throughout the gas loop, upstream and downstream of the meter;

- •

- For the gas metering, validation of the flow rate, cumulative volume, and environmental quantity measurements (temperature, pressure).

- •

- Condition (a): atmospheric pressure: 884 mbar; temperature: 27.0 °C.

- •

- Condition (b): atmospheric pressure: 889 mbar; temperature: 25.5 °C.

3.2. Communication and Blockchain Architecture

3.2.1. The Energy Market

- •

- Cash flow and liquidity pool: All the available energy tokens are recorded in the ledger;

- •

- Deposit: All the producers deposit energy tokens;

- •

- Withdrawals: All the consumers withdraw tokens according to the energy use;

- •

- Arbitration: The distributor acquires tokens from a prosumer, selling them to a final consumer;

- •

- Immediate settlement: All transactions are irreversible and immediately recorded.

3.2.2. The Mechanism of Distributed Validation

- •

- Authority minimum number: three nodes (to avoid single failure points);

- •

- Consensus threshold: + 0.01 (almost 67% of the authorities approve);

- •

- Blockage time: 30 s (trade-off between reaction time and stability).

- •

- Anti-Double Spending:

- Univocal cryptographic UUID for each token;

- A distributed database tracks the status of each token (created/consumed/transferred);

- Atomic lock during concurrent transactions.

- •

- Validation of Production

- Digital certification of the production plant;

- Compliance with the allowed ranges;

- Optional integration of other monitoring systems.

3.2.3. Transactions and Token Flow

- •

- Token creation;

- •

- Token consumption (final consumer/prosumer);

- •

- Token transfer (between actors).

3.2.4. Token Life Cycle

- Edge Layer (GasMeter Node → Aggregator): Edge nodes generate transactions signed with Ed25519 (average payload 775–835 bytes) and transmit them via MQTT to the aggregator node. Average latency measured in the GNS3 test environment: 50–150 ms on a simulated local network.

- Aggregation Layer (Batch Processing): The aggregator collects transactions into batches with a configurable interval via the BATCH_INTERVAL_SECONDS environment variable (set to 30 s in the tests). The service constructs the Merkle root and validates the data structure. The average batch processing time is 200–500 ms for sizes varying from 5 to 50 transactions (MIN_BATCH_SIZE and MAX_BATCH_SIZE).

- Blockchain Layer (Smart Contract Execution): The smart contract’s submitBatch () function executes the following atomic operations:

- Batch parameter validation (presence of at least one transaction, correctness of arrays);

- Registration of the batch in the blockchain with block.timestamp;

- Iteration over all transactions in the batch with an anti-duplication check via mapping;

- On-chain storage of cryptographic hashes and transaction metadata;

- Emission of BatchSubmitted and TransactionRecorded events for traceability.

3.2.5. Management of the Distributed Ledger

- •

- Created: Token generated and available for use;

- •

- Transferred: Token transferred between actors (it is available);

- •

- Consumed: Token used to assess consumption (final status).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Montuori, L.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Vargas-Salgado, C.; Mansó-Borràs, I. Enabling the Natural Gas System as Smart Infrastructure: Metering Technologies for Customer Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 Global Congress on Electrical Engineering (GC-ElecEng), Valencia, Spain, 5–7 August 2020; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- D’Emilia, G.; Gaspari, A.; Natale, E.; Adduce, G.; Vecchiarelli, S. All-Around Approach for Reliability of Measurement Data in the Industry 4.0. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2021, 24, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascetta, F.; Rotondo, G.; Piccato, A.; Spazzini, P.G. Calibration Procedures and Uncertainty Analysis for a Thermal Mass Gas Flowmeter of a New Generation. Measurement 2016, 89, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celenza, L.; Dell’Isola, M.; Ficco, G.; Vigo, P.; Bertoli, E.; Incerti, L.; Zocchi, T. Critical Aspects of New Domestic Static Gas Meter. In Proceedings of the 2015 XVIII AISEM Annual Conference, Trento, Italy, 3–5 February 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ficco, G.; Dell’Isola, M.; Graditi, G.; Monteleone, G.; Gislon, P.; Kulaga, P.; Jaworski, J. Reliability of Domestic Gas Flow Sensors with Hydrogen Admixtures. Sensors 2024, 24, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, R.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, K. Signal Processing Method of Ultrasonic Gas Flowmeter Based on Transit-Time Mathematical Characteristics. Measurement 2025, 239, 115485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gan, Q.; He, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L. Research on the Influence of Sensor Installation Arrangement on Online Measurement of External Clamp-on Ultrasonic Flowmeter. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC), Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2024; Volume 6, pp. 1547–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Bekraoui, A.; Hadjadj, A. Thermal Flow Sensor Used for Thermal Mass Flowmeter. Microelectron. J. 2020, 103, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, J.; Dudek, A. Study of the Effects of Changes in Gas Composition as Well as Ambient and Gas Temperature on Errors of Indications of Thermal Gas Meters. Energies 2020, 13, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficco, G.; Frattolillo, A.; Malengo, A.; Puglisi, G.; Saba, F.; Zuena, F. Field Verification of Thermal Energy Meters through Ultrasonic Clamp-on Master Meters. Measurement 2020, 151, 107152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sammak, K.A.; Al-Gburi, S.H.; Marghescu, I.; Drăgulinescu, A.-M.C.; Marghescu, C.; Martian, A.; Al-Sammak, N.A.H.; Suciu, G.; Alheeti, K.M.A. Optimizing IoT Energy Efficiency: Real-Time Adaptive Algorithms for Smart Meters with LoRaWAN and NB-IoT. Energies 2025, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhari, M.; Saeed, N.; Alouini, M.-S.; Amhoud, E.M. A Survey on Scalable LoRaWAN for Massive IoT: Recent Advances. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1841–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Spinozzi, P.; Natale, E.; D’Emilia, G.; Ferri, G.; Stornelli, V. A LoRa-based Smart Gas Meter for Civil and Industrial Applications. In Proceedings of the SIE 2024, LV Annual Meeting of the Italian Society of Electronics, Genoa, Italy, 26–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Divya, G.; Supraja, P. Bids and Asks: Blockchain-Based Peer-to-Peer Trading Platform. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 119, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, J.M.; Sadat, S.A.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. Using a Ledger to Facilitate Autonomous Peer-to-Peer Virtual Net Metering of Solar Photovoltaic Distributed Generation. Sol. Energy Adv. 2024, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrea, D.; Toderean, L.; Cioara, T.; Anghel, I.; Antal, M. Smart Contracts and Homomorphic Encryption for Private P2P Energy Trading and Demand Response on Blockchain. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickhoff, M.; Exner, A.; Busboom, A. Energy Consumption Tokens for Blockchain-Based End-to-End Trading of Green Energy Certificates. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES GTD International Conference and Exposition (GTD), Istanbul, Turkey, 22–25 May 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Merrad, Y.; Habaebi, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Gunawan, T.S.; Elsheikh, E.A.A.; Suliman, F.M.; Mesri, M. Machine Learning-Blockchain Based Autonomic Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading System. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEN EN 14236:2018; Ultrasonic Domestic Gas Meters. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- European Parliament and Council. 2014/32/EU—Directive 2014/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the Harmonisation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to the Making Available on the Market of Measuring Instruments; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC Guide 98-3:2008; Uncertainty of Measurement—Part 3: Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

| Property | Diaphragm Meter [1,5] | Thermal Meter [1,4,5,8,9,10] | Ultrasonic Meter [1,3,5,6,7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Medium | High | Very high |

| Pressure Loss | High (due to mechanical parts) | Very low | Very low |

| Durability | High (mechanical, long lifespan) | Medium (sensor drift over time) | High (no moving parts) |

| Size | Bulky (especially for high flow rates) | Compact | Compact |

| Dependence on Gas Composition | Low | Very high (based on thermal properties of the gas) | Low (if the gas is homogeneous) |

| Maintenance Requirements | Medium (moving parts require periodic checks) | Medium–high (sensor recalibration) | Low (no moving parts) |

| Response time | Slow | Fast | Very fast |

| Ease of conversion to smart meter | Low | High | Very high |

| Step N# | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Token generation | All authorized actors (distributor, prosumer, domestic user) assess energy production and require token creation |

| Step 2 | Validation and registration | A consensus is issued following validation by the network, registering the relevant tokens in the ledger |

| Step 3 | Trading/allocation | Tokens are exchanged between actors or allocated for direct consumption |

| Step 4 | Consumption and extinction | The final users “fire” tokens after their use |

| N# | Role | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Domestic producer “DP” (with some solar panels) | Deposits 100 tokens |

| 2 | Distributor | Buys 100 from “DP” |

| 3 | A group of consumers | Buys 80 tokens from distributor as a unique consumer |

| 4 | Distributor | Keeps 20 tokens in the ledger |

| N# | Role | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Distributor (photovoltaic plant) | Deposits 10,000 tokens |

| 2 | Industrial user | Buys 3000 tokens from the distributor |

| 3 | Domestic customer | Buys 5000 tokens from distributor |

| 4 | Distributor | Keeps 2000 tokens in the ledger |

| N# | Role | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edge Node | Sends transaction to an aggregator |

| 2 | Aggregator | Pre-validates and aggregates in batch |

| 3 | Aggregator | Sends batch to 3 + nodes and authority |

| 4 | Authority 1/5 | Independently validates the batch given its outcome |

| 5 | Authority 2/5 | Independently validates the batch given its outcome |

| 6 | Authority 4/5 | Independently validates the batch given its outcome |

| 7 | Authority | If 67%+ of the authority outcomes are positive, the batch is created and shared |

| 8 | All nodes | Update their local site |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiominto, L.; D’Emilia, G.; Esposito, P.; Ferri, G.; Natale, E.; Polverini, D.; Spinozzi, P.; Stornelli, V.; Chiavaroli, L. A New and Smart Gas Meter with Blockchain Validation for Distributed Management of Energy Tokens. Eng 2025, 6, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6110290

Chiominto L, D’Emilia G, Esposito P, Ferri G, Natale E, Polverini D, Spinozzi P, Stornelli V, Chiavaroli L. A New and Smart Gas Meter with Blockchain Validation for Distributed Management of Energy Tokens. Eng. 2025; 6(11):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6110290

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiominto, Luciano, Giulio D’Emilia, Paolo Esposito, Giuseppe Ferri, Emanuela Natale, Dario Polverini, Paolo Spinozzi, Vincenzo Stornelli, and Luca Chiavaroli. 2025. "A New and Smart Gas Meter with Blockchain Validation for Distributed Management of Energy Tokens" Eng 6, no. 11: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6110290

APA StyleChiominto, L., D’Emilia, G., Esposito, P., Ferri, G., Natale, E., Polverini, D., Spinozzi, P., Stornelli, V., & Chiavaroli, L. (2025). A New and Smart Gas Meter with Blockchain Validation for Distributed Management of Energy Tokens. Eng, 6(11), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6110290