1. Introduction

The increasing global energy demand, coupled with the progressive depletion of conventional light crude oils, has driven the petroleum industry towards the increased utilization of heavy crude oils, bitumen, and residual fractions [

1,

2]. These heavy feedstocks pose significant challenges for refining due to their high concentrations of impurities, particularly heteroatoms and metal compounds, with vanadium being one of the most abundant and detrimental [

3,

4]. A substantial portion of these vanadium compounds exists in the form of vanadyl porphyrins, where the metal ion is chelated within a macrocyclic porphyrin structure. Vanadium deposits irreversibly on the catalyst, leading to pore blockage, active site poisoning, and catalyst deactivation during crucial catalytic cracking and hydrotreating processes [

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, the development of efficient methods for removing vanadium from heavy oils is a critical topic in the petrochemical industry.

The conventional technologies that are applied to remove vanadium from heavy oils mainly include solvent deasphalting [

8] and hydrodemetallization (HDM) [

3]. Solvent deasphalting, while effective, often results in a loss of valuable oil components due to the nonselective separation [

9]. Although HDM can selectively remove vanadium from heavy oils, the technology still has several limitations, including severe operating conditions (high temperature and pressure), high hydrogen consumption, and catalyst deactivation due to metal deposition [

10]. Adsorptive demetallization (ADM) is considered a promising alternative due to its potential for lower energy consumption, operational simplicity, and the possibility of adsorbent regeneration. The central challenge for an adsorptive process, however, lies in achieving high selectivity for vanadyl porphyrins against a complex background of competing species in heavy oils.

A wide variety of solid adsorbents have been explored for metalloporphyrin removal, such as silica gel [

11], alumina [

12,

13], clay minerals [

14], activated carbons [

15,

16], graphene [

17], zeolite [

18,

19], etc. In addition to the single adsorbent, composite adsorbent such as chitosan/zeolite was also reported for metal porphyrins adsorption from crude oils [

20]. Most of these studies only focus on the adsorption of metalloporphyrin itself. However, petroleum contains a large number of compounds with structures similar to metalloporphyrins, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The adsorption effects of these compounds on metalloporphyrins remain underexplored in the literature.

Conventional adsorbents, such as silica gel and alumina, are widely employed as stationary phases for separating and enriching vanadyl porphyrins in petroleum [

21]. However, their lack of specificity often leads to the co-adsorption of other polar compounds. To address this limitation and improve selectivity, researchers have turned to the strategic functionalization of adsorbent surfaces with specific chemical groups designed for preferential interaction with metalloporphyrins. Given that the central vanadium (V

4+) and nickel (Ni

2+) in metalloporphyrins are Lewis acidic, the introduction of Lewis basic sites, such as nitrogen-containing functional groups, onto the adsorbents provides a pathway for selective adsorption through coordinated interaction [

22,

23]. Xu et al. [

24] reported the separation of vanadyl and nickel porphyrins on an aminopropyl column (aminopropyl groups chemically bonded to silica gel), which provides better selectivity compared to silica columns. The author points out that this high selectivity may be due to hydrogen bonding as well as Van der Waals interactions between metalloporphyrins and the amino group on the column surface [

24]. However, in our previous research, we found that metalloporphyrins are more likely to axially coordinate with alkaline groups compared to hydrogen bonding interactions [

22,

23], which indicates that the high selectivity of the aminopropyl column towards metalloporphyrin may be mainly influenced by axial coordination interactions. This interaction provides an important foundation for designing highly selective metalloporphyrin adsorbents.

A deep understanding of the adsorption process necessitates a systematic investigation into its kinetics, equilibrium, and thermodynamics. Kinetic models are essential for identifying the adsorption rate and potential rate-controlling steps [

25]. Isotherm models provide insights into adsorption capacity, surface heterogeneity, and the nature of the adsorbate–adsorbent interactions [

26]. Furthermore, thermodynamic parameters reveal the spontaneity and energy exchange of the process. An integrated analysis using these tools is crucial for elucidating the fundamental mechanisms and for guiding the optimization of the adsorption process.

Here in this study, vanadyl octaethylporphyrin (VOOEP) and 1-methylpyrene (1-MP) were selected as model compounds. The adsorption efficiency and selectivity of VOOEP on different solid adsorbents were investigated in the presence of 1-MP to evaluate the effect of PAHs on VOOEP adsorption. The adsorbents used in this work include silica gel, alumina, graphene, molecular sieve, activated carbon, etc., and chemical group-modified adsorbents (aminated graphene and primary secondary amine (PSA) adsorbent). Some adsorbents showing high performance were further tested using a real heavy deasphalted oil (HDAO) to validate their practical applicability. The most promising adsorbent, PSA, was then selected for an in-depth mechanistic investigation. The effects of PSA dosage, temperature, and initial adsorbate concentration on the adsorption process of VOOEP and 1-MP were examined, and the data were fitted to four kinetic models, including pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intraparticle diffusion models. Additionally, adsorption isotherms were determined and modeled by applying the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) models to gain further insight into the adsorption mechanisms. Thermodynamic studies were also conducted to elucidate the nature of the adsorption process.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Reagents and Samples

Vanadyl octaethylporphyrin (VOOEP) and 1-methylpyrene (1-MP) were purchased from J&K Chemical Ltd. (Beijing, China). N-heptane, methanol, toluene, and dichloromethane solvents were obtained from the Beijing Chemical Reagents Company (Beijing, China). They were purified by distillation before use. A heavy deasphalted oil (HDAO) derived from Venezuela Orinoco vacuum residue through the solvent deasphalting process was used in this study.

The adsorbents used in the experiment are detailed in

Table 1. Silica gel, molecular sieve, activated carbon, and alumina (Al

2O

3, neutral, acidic, and basic) were dehydrated in an oven at 120 °C for 3.5 h before use. Activated alumina was activated at 350 °C for 4 h.

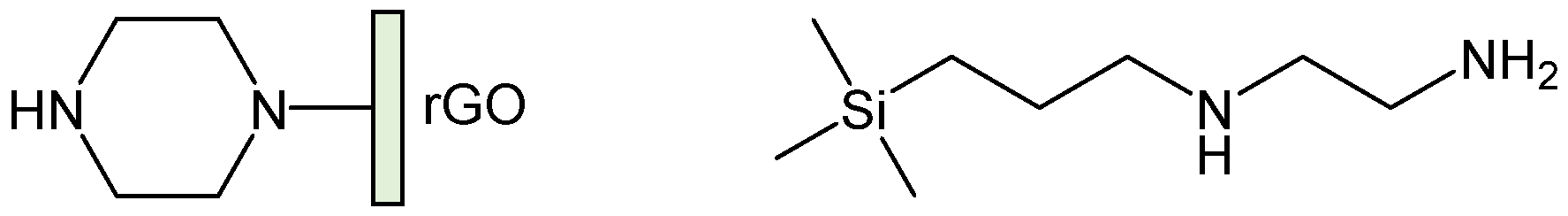

The structure of aminated graphene and primary secondary amine adsorbent (PSA) is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Adsorption Experiment of VOOEP/1-MP Mixed Standard

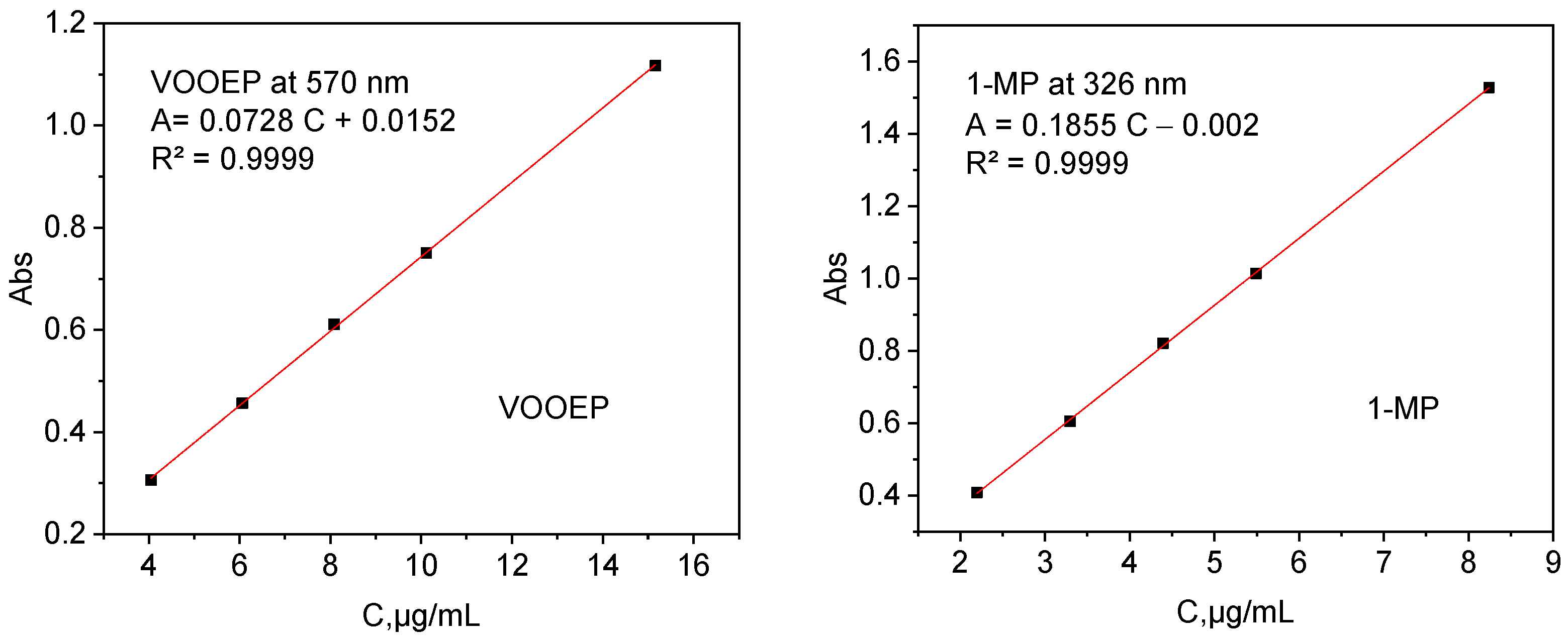

A mixed standard solution of VOOEP and 1-MP, denoted as VOOEP/1-MP, was prepared in n-heptane with concentrations of 15.16 μg/mL for VOOEP and 8.25 μg/mL for 1-MP. The primary reason for using non-equivalent concentrations was to compensate for the difference in their molar absorptivity (extinction coefficient) at our chosen detection wavelengths (~570 nm for VOOEP and ~326 nm for 1-MP), to simultaneously quantify both VOOEP and 1-MP in the mixture. The individual UV-Vis spectra of VOOEP and 1-MP are shown in the

Supplementary Information Figure S1. The concentrations of VOOEP and 1-MP in the mixture were determined using standard curves (as shown in

Figure 2), which show high correlation coefficients (R

2 > 0.999).

Approximately 0.8 g of adsorbent was weighed into a 50 mL conical flask, followed by the addition of 10 mL VOOEP/1-MP solution. The flask was placed in a constant-temperature water bath shaker at 20 °C for 24 h. The UV-Vis absorbance of the mixed solution after adsorption was measured, and the concentrations of VOOEP and 1-MP were calculated from the standard curves.

The adsorption percentage (

η), equilibrium adsorption capacity (

qe), and the adsorption selectivity (

α) of VOOEP relative to 1-MP for different adsorbents were calculated using Equations (1)–(3), respectively:

Here, qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity of the adsorbent for the model compound (mg/g), C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of the model compound (mg/L), V is the volume of the mixed solution (L), and m is the dosage of the adsorbent used (g).

2.3. HDAO Adsorption–Desorption Experiments

Approximately 0.8 g of HDAO was weighed into a 50 mL conical flask and fully dissolved in 40 mL of n-heptane via ultrasonication. A pre-weighed amount of adsorbent was then added to achieve adsorbent-to-oil mass ratios of approximately 0.33. The flask was placed in a constant-temperature water bath shaker at 20 °C for 24 h. Then the remaining oil and the adsorbent were separated by centrifuge. The separated adsorbent was transferred to a solid phase extraction (SPE) column. Sequential elution was performed using n-heptane, toluene, a toluene/methanol mixture (50:50, v/v), and finally methanol to obtain the adsorbed oil. Both the remaining oil and the adsorbed oil were analyzed by positive-ion electrospray ionization (+ESI) Orbitrap mass spectrometry (MS) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) for elemental analysis. The HDAO samples were diluted by a toluene/methanol mixture (50:50, v/v) to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL to infuse into MS. The +ESI MS operating conditions were as follows: spray voltage 3600 V, ion transfer tube temperature 300 °C, nitrogen sheath gas flow rate 8.0 arbitrary units (au), auxiliary gas flow rate 3.0 au, mass range m/z 200–1000. Regarding the ICP-OES analysis, the detailed procedure was as follows: The HDAO samples were first burned at 750 °C for 5 h, and the resulting ash was dissolved in a HNO3–HCl mixture solution (acid digestion), then diluted to 10 mL with water to be analyzed by ICP-OES. The quantification of vanadium was performed using ICP-OES at the V emission line of 292.460 nm.

A blank experiment, following the same procedure but without the addition of adsorbent, was conducted concurrently.

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics Experiments

The adsorption kinetics of the VOOEP/1-MP mixed solution onto PSA were investigated by examining the effects of initial adsorbate concentration, PSA dosage, and adsorption temperature. PSA masses of 10 mg, 10 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, and 20 mg were weighed into sealed quartz cuvettes. Then, 3 mL of the VOOEP/1-MP mixed solution was added, with initial VOOEP concentrations of 6, 10, 14, 14, and 14 μg/mL, respectively. The quartz cuvettes were placed in a constant-temperature water bath shaker and agitated at 150 rpm, maintaining a temperature of 20 °C. The UV-Vis absorbance of the mixed solution was analyzed at regular intervals to determine the concentrations of VOOEP and 1-MP at different times using the standard curves. The adsorption capacity (

qt) of PSA for VOOEP and 1-MP at different times was calculated using Equation (4). The procedure was repeated at temperatures set to 15 °C and 25 °C.

Here, qt is the adsorption capacity of PSA for the model compound at time t (mg/g); C0 is the initial concentration of the model compound (mg/L); Ct is the concentration of the model compound in the solution at time t (mg/L); V is the volume of the mixed solution (L); and m is the dosage of PSA used (g).

2.5. Adsorption Thermodynamics Experiments

Briefly, 20 mg PSA was added to each of five 50 mL conical flasks containing 10 mL VOOEP/1-MP mixed solution with initial VOOEP concentrations of 4, 6, 8, 10, and 14 μg/mL, respectively. The flasks were placed in a constant-temperature water bath shaker and agitated at 150 rpm for 24 h at 20 °C to reach adsorption equilibrium. The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) of PSA for VOOEP and 1-MP was calculated using Equation (2). The procedure was repeated at temperatures set to 25 °C and 30 °C.

2.6. Theoretical Models

This study primarily employed four common kinetic models (listed in

Table 2) for data fitting: pseudo-first-order [

27], pseudo-second-order [

28,

29], Elovich [

30], and intraparticle diffusion models [

31,

32]. Three adsorption isotherm models were used to fit the experimental data in this study: the Langmuir [

33], Freundlich [

34,

35], and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) [

36] isotherm models. The thermodynamic parameters such as enthalpy change (ΔH; kJ/mol), entropy change (ΔS; J/(mol K)), and Gibbs free energy change (ΔG; kJ/mol), were determined to evaluate the energy variation during the adsorption process. ΔH, ΔS, and ΔG can be calculated using the equations in

Table 3.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption Results of Different Adsorbents for VOOEP/1-MP

The adsorbents used in the adsorption process included silica gel, alumina, graphene, molecular sieve, activated carbon, PSA, aminated graphene, etc. Based on the experimental results in our previous study [

22], VOOEP readily undergoes strong axial coordination with basic nitrogen compounds. Adsorbents (e.g., PSA and aminated graphene) modified with basic amine functional groups were selected to investigate the effect of these groups on VOOEP adsorption.

The initial phase of this study involved a systematic screening of different adsorbents to evaluate their efficiency and, more importantly, their selectivity in adsorbing VOOEP from a solution containing a competing PAH, such as 1-MP. The adsorption results of different adsorbents for VOOEP and 1-MP are summarized graphically in

Figure 3 (left: adsorption percentage; right: adsorption selectivity for VOOEP relative to 1-MP). An effective adsorbent should have high adsorption capacity for VOOEP and low adsorption for 1-MP. As shown in

Figure 3, the order for adsorption percentage and selectivity differed significantly. The order of adsorption percentage for VOOEP among different adsorbents is as follows: graphene ≈ molecular sieve ≈ silica gel ≈ PSA ≈ NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst ≈ activated alumina ≈ neutral Al

2O

3 ≈ acidic Al

2O

3 ≈ activated carbon > basic Al

2O

3 > GSH > aminated graphene. The adsorption selectivity of VOOEP has the following order: basic Al

2O

3 > GSH > molecular sieve ≈ PSA > NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst > silica gel > neutral Al

2O

3 > acidic Al

2O

3 > activated alumina > activated carbon > graphene > aminated graphene. The PSA, molecular sieve, and NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst simultaneously exhibited relatively high VOOEP adsorption percentage and selectivity, making them more effective adsorbents for VOOEP. Basic Al

2O

3 has the highest adsorption selectivity, but with a much lower adsorption capacity. Compared to graphene, the sharp decrease in adsorption for both VOOEP and 1-MP on aminated graphene implies that piperazine modification introduces steric hindrance, blocking adsorbates’ access to the adsorption sites. It also indicates that VOOEP and 1-MP mainly interact with the polyaromatic structure of graphene and aminated graphene, which is consistent with literature results [

17]. In contrast, functionalizing silica gel (PSA) with primary and secondary amine groups markedly improved adsorption selectivity without sacrificing VOOEP capacity. The amine groups introduced into the silica surface are strong Lewis bases, which can coordinate with the Lewis acidic V

4+ center of VOOEP [

22]. This specific coordination competes effectively against non-specific interactions, thereby suppressing 1-MP co-adsorption and making PSA with its high selectivity, second only to basic Al

2O

3.

In the above experiments, the concentrations of VOOEP and 1-MP in the prepared mixed solution did not match the actual concentration in heavy oil in order to compare the adsorption performance of different adsorbents for both VOOEP and 1-MP. The content of PAHs in heavy oils is much higher than that of metalloporphyrins. To simulate this condition, we conducted adsorption experiments where the concentration ratio of 1-MP to VOOEP was increased to 260, far exceeding the actual ratio in many heavy oils.

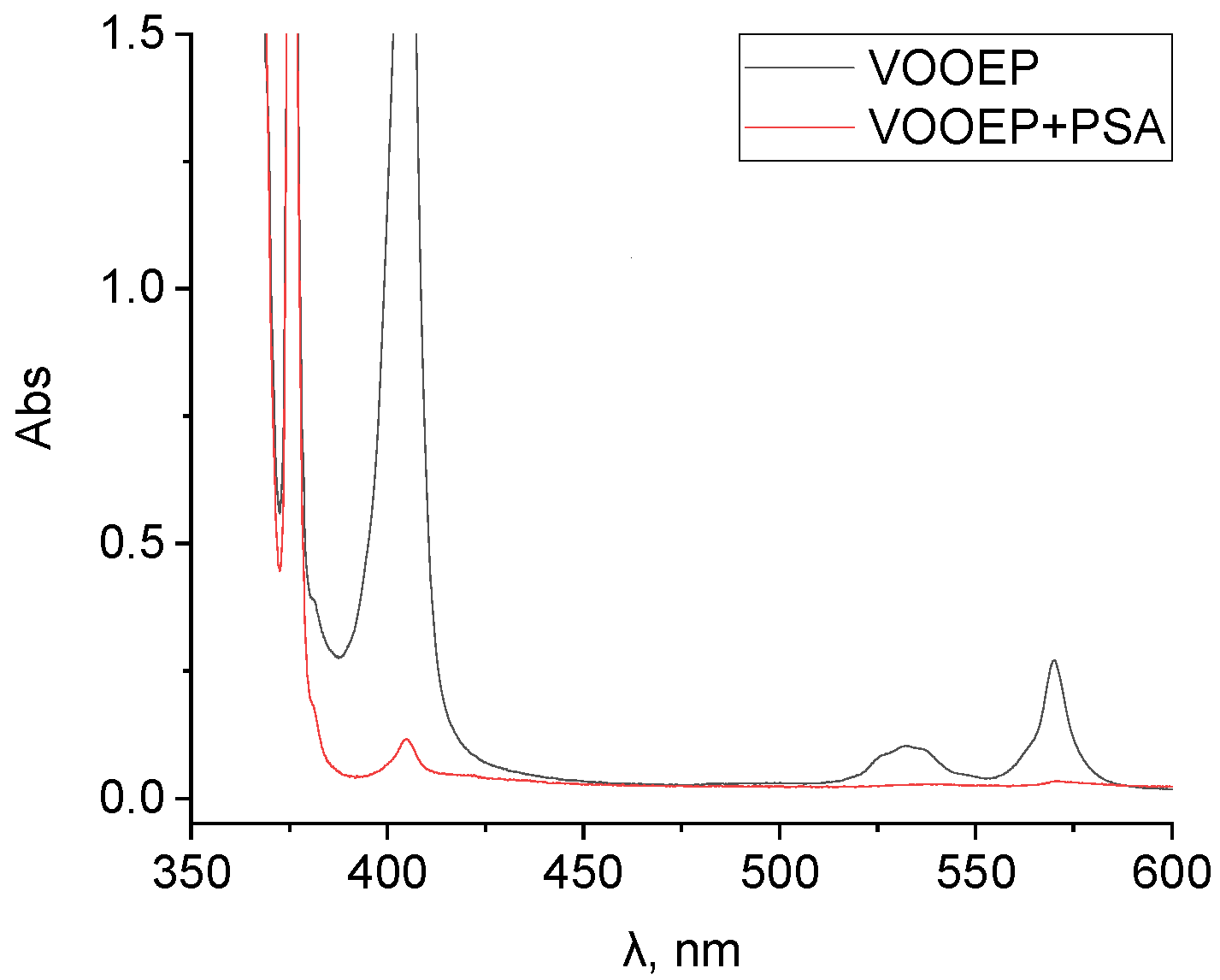

The UV-Vis spectra of the VOOEP/1-MP solution before and after PSA adsorption are shown in

Figure 4. After PSA adsorption, the absorption band of VOOEP was basically undetectable. The adsorption percentage of VOOEP on PSA remained exceptionally high (99.37%) even at this extreme 1-MP to VOOEP concentration ratio of 260, nearly identical to its performance (99.80%) at a much lower ratio of 0.55. This demonstrates that the adsorption of VOOEP onto PSA is virtually unaffected by a large excess of 1-MP, confirming its superior selectivity. This excellent performance is attributed to the strong axial coordination between the amine groups on PSA and the VOOEP molecule, which enables PSA to preferentially capture vanadyl porphyrins even in the presence of high concentrations of competing PAHs.

3.2. Adsorption of Vanadium Compounds in HDAO

To assess practical applicability, the adsorption was extended from model compound systems to a real heavy deasphalted oil (HDAO). Molecular sieve, PSA, NiMo/Al2O3 catalyst, and basic Al2O3 (which showed the highest selectivity) were selected for adsorption experiments targeting vanadium compounds in HDAO. The adsorption performance of each adsorbent was compared based on the mass yield, V content of the remaining oil, and the molecular composition of vanadyl porphyrins.

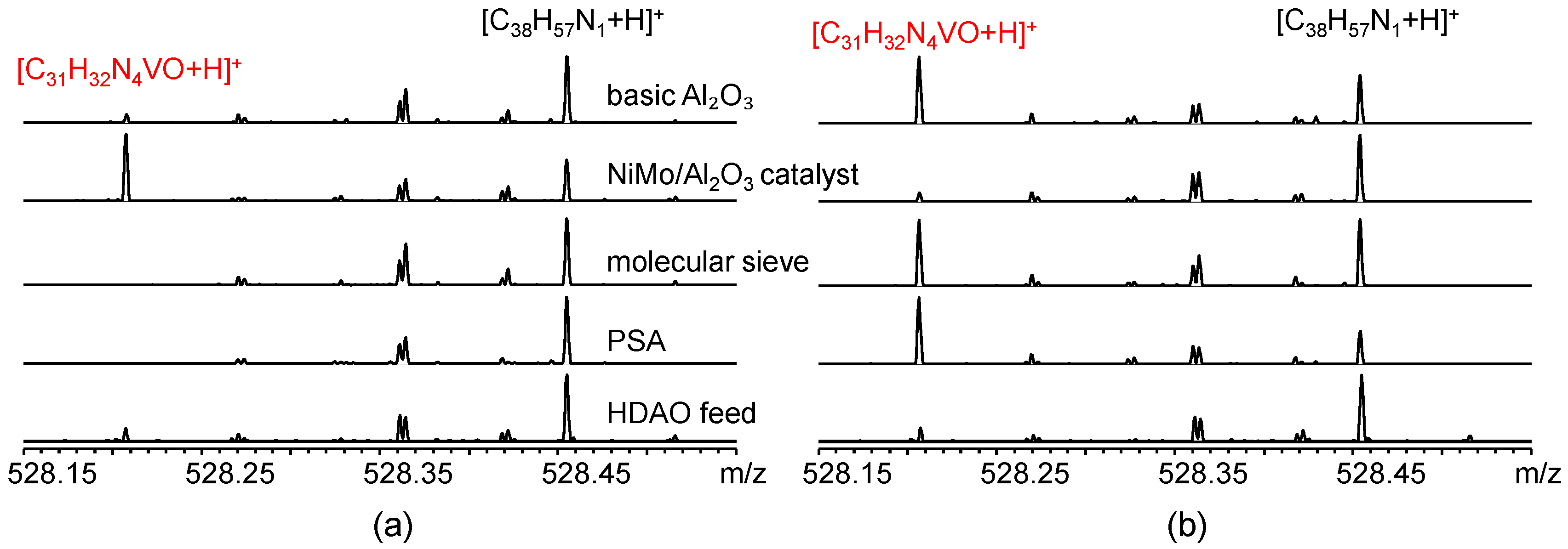

Figure 5 shows the +ESI Orbitrap MS spectra at

m/

z 528 of the remaining oil and adsorbed oil by various adsorbents. The peak at

m/

z 528 corresponds to the [M+H]

+ ion of a common vanadyl porphyrin species (C

31H

32N

4VO) present in HDAO. This species is representative of the N

4VO class and is abundant in the mass spectra, making it a suitable marker for tracking vanadyl porphyrin adsorption. N

4VO class compounds were detected with a certain abundance in the remaining oil after adsorption on basic Al

2O

3 and NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst. The result of the NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst was very different from the model system observed in

Section 3.1. NiMo/Al

2O

3 hydrogenated desulfurization catalyst has high-affinity active sites for sulfur compounds. In the model system (VOOEP/1-MP in n-heptane), the NiMo/Al

2O

3 catalyst can adsorb a significant amount of VOOEP, leading to the relatively high adsorption percentage. However, when applied to the real HDAO feedstock, which has a high complexity and a sulfur content of 4.5 wt%, the situation changes dramatically. The catalyst is likely oversaturated by the abundant sulfur-containing compounds (e.g., thiophenes, sulfides) present in the oil. These sulfur compounds compete very effectively for the limited active sites, thereby suppressing the adsorption of vanadyl porphyrins. In contrast, these vanadyl porphyrin compounds were barely detected in the remaining oil after adsorption on PSA and molecular sieve. Instead, they were abundantly detected in the corresponding adsorbed oils obtained by solvent elution of the spent PSA and molecular sieve. Comparatively, molecular sieve and PSA are better adsorbents for vanadyl porphyrins in HDAO.

The quantitative results from ICP-OES analysis were summarized in

Table 4. After PSA adsorption, the mass yield of the remaining oil (78.13%) is close to the n-heptane soluble fraction (81.13%) of HDAO obtained without adsorbent (blank). However, the V content in the remaining oil decreased to 222 µg/g, and the V mass yield was only 54.07%. This means nearly 46% of the total vanadium was removed by PSA and concentrated in the adsorbed oil, which had a very high V content of 707 µg/g.

At the same adsorbent-to-oil ratio, the mass yield of the remaining oil after adsorption on molecular sieve was about 22% lower than that after PSA adsorption, indicating that molecular sieve adsorbed a large quantity of non-metallic components (e.g., large aromatics). The V content in its adsorbed oil (547 µg/g) was lower than that for PSA, and the V mass yield in the remaining oil was 31.91%, meaning 68.09% of V was removed. While this removal efficiency is high, the low remaining oil yield represents a significant loss of desirable oil.

The comparison indicated that PSA has higher adsorption selectivity for vanadium compounds, removing them efficiently with lower adsorption of other components in oil. Molecular sieve, while it can effectively remove vanadium compounds, is less selective, leading to a higher loss of heavy oil. In addition, the total mass yield (remaining oil + adsorbed oil) of both adsorbents exceeded 98%, indicating that adsorption is largely reversible, and the adsorbed compounds can be effectively recovered through solvent elution, thereby minimizing irreversible adsorbent contamination.

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics Study

The results from model compounds and HDAO adsorption indicated that PSA shows strong adsorption capacity and selectivity for vanadium compounds. To further investigate the adsorption mechanism of PSA for vanadium compounds, the effects of PSA dosage, temperature, and initial adsorbate concentration on the adsorption process of VOOEP/1-MP mixed standard were examined. The data were fitted to kinetic models for a more detailed analysis of the adsorption mechanism and the rate-determining step.

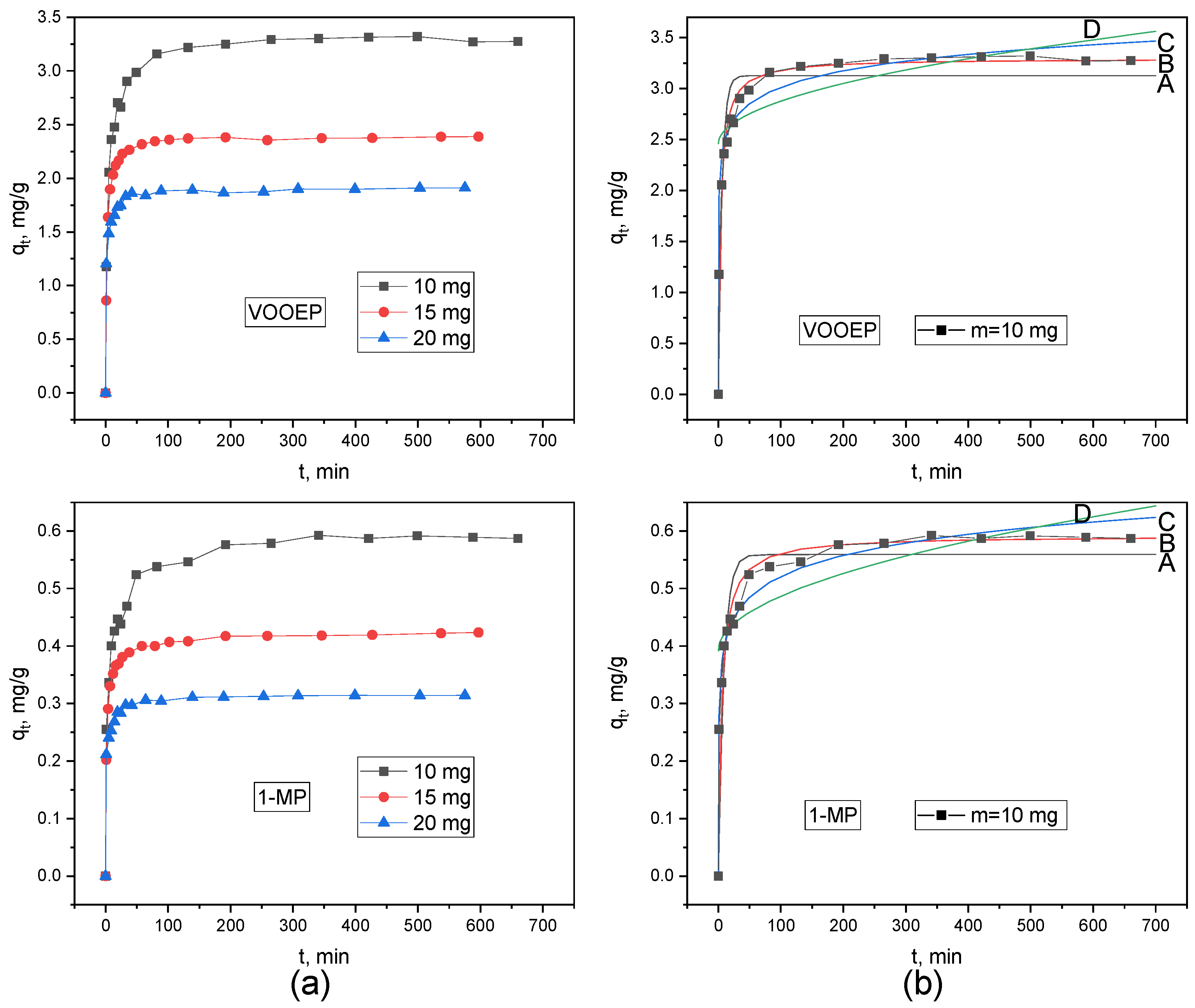

3.3.1. Effect of PSA Dosage

Figure 6a shows the experimental curves for the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA at different adsorbent dosages. The overall trends of all curves are similar. At the beginning of adsorption (t < 100 min), the adsorption rate for both VOOEP and 1-MP is fast, and the adsorption capacity increases rapidly due to the abundance of vacant adsorption sites on PSA. As adsorption proceeds, the number of available sites on PSA gradually decreases, slowing down the adsorption rate for VOOEP and 1-MP. The increase in adsorption capacity gradually slows and eventually reaches equilibrium. As the PSA dosage increased from 10 mg to 20 mg, the equilibrium adsorption capacity (

qe) for both VOOEP and 1-MP decreased (from 3.28 to 1.91 mg/g for VOOEP; from 0.59 to 0.31 mg/g for 1-MP). For a fixed initial adsorbate concentration and volume, increasing the adsorbent dosage provides more total sites but reduces the amount adsorbed per unit mass because the adsorbate-to-adsorbent ratio is lower. Crucially, at every dosage, the

qe of VOOEP was significantly higher than that of 1-MP, indicating the preferential adsorption of PSA for VOOEP.

The experimental data were fitted using the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intraparticle diffusion models. The fitting results are shown in

Figure 6 and

Supporting Information Figure S2. The fitting parameters and correlation coefficients (R

2) are listed in

Table 5. Comparing the fitting results, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model yielded the highest R

2 values for the adsorption of both VOOEP and 1-MP. The calculated equilibrium adsorption capacities (

qe,cal) from this model agreed well with the experimental equilibrium adsorption capacities (

qe,exp). This indicates that the adsorption process of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA was well described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, suggesting that the adsorption process involves electron sharing or exchange between PSA and the VOOEP/1-MP model compounds [

37,

38]. Furthermore, the pseudo-second-order rate constant (

k2) for both VOOEP and 1-MP increased with increasing PSA dosage. The available adsorption sites on the PSA surface were limited at low PSA dosage. A higher PSA dosage provides a greater surface area and more available active sites, reducing the diffusion path length and thus accelerating the overall adsorption rate for VOOEP and 1-MP.

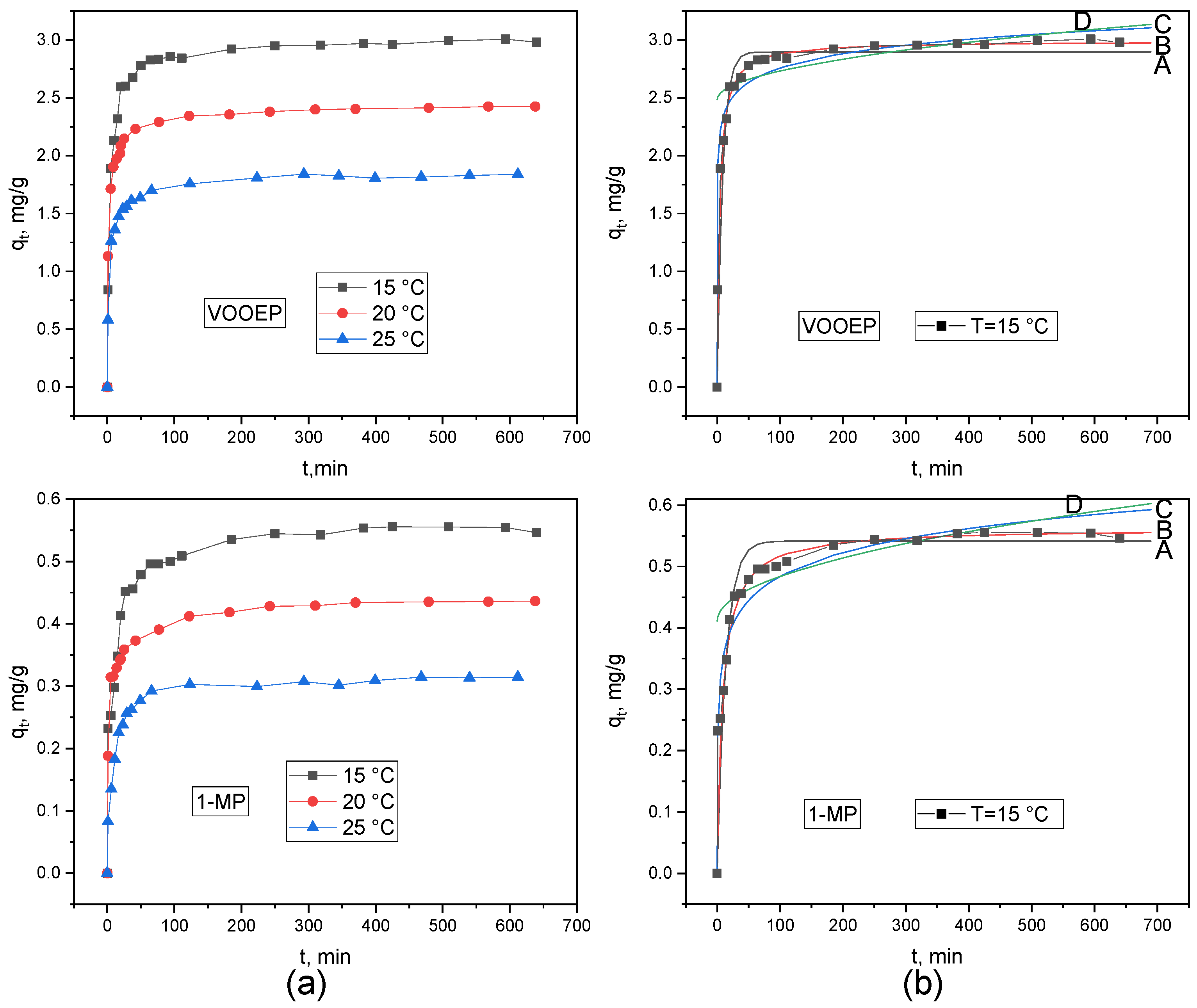

3.3.2. Effect of Temperature

The effect of temperature on the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA is shown in

Figure 7a. The overall trends of all curves are similar to those in

Figure 6. As the temperature increased from 15 °C to 25 °C, the

qe for VOOEP decreased from 2.98 mg/g to 1.84 mg/g, and for 1-MP it decreased from 0.55 mg/g to 0.32 mg/g. The increase in temperature led to a decrease in the adsorption capacity for both compounds, indicating that the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA is an exothermic process. Lower temperatures favor the adsorption reaction. Consistent with the results at different PSA dosages, the

qe of PSA for VOOEP was consistently higher than that for 1-MP at different temperatures.

The experimental data at different temperatures were fitted using the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intraparticle diffusion models. The fitting results are depicted in

Figure 7 and

Supporting Information Figure S3, and the fitting parameters are given in

Table 6. Consistent with the results at different PSA dosages, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model fits the adsorption process of both VOOEP and 1-MP well. The

qe,cal obtained from this model agreed well with the

qe,exp. As the temperature increased, the

k2 for the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP also increased. Higher temperatures accelerate the diffusion and collision frequency between adsorbate and PSA, thereby increasing their adsorption rate on PSA, which favors faster adsorption.

3.3.3. Effect of Initial Adsorbate Concentration

The effect of the initial adsorbate concentration on the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA was also studied, and the results were illustrated in

Figure 8a. The overall trends of all curves are similar to those in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. As the initial adsorbate concentration increased, the

qe of PSA for both VOOEP and 1-MP also increased. The increase in the initial concentration of VOOEP and 1-MP provides a greater mass transfer driving force (concentration gradient) to some extent. The mass transfer resistance from the bulk solution to the adsorbent surface decreases, allowing more VOOEP and 1-MP to be adsorbed onto the adsorbent. Throughout all kinetic studies—varying PSA dosage, temperature, and initial adsorbate concentration—the adsorption capacity of VOOEP was consistently and significantly higher than that of 1-MP, demonstrating the strong selectivity of PSA for VOOEP.

The experimental data at different initial concentrations were fitted to the kinetic models. The fitting results are shown in

Figure 8 and

Supporting Information Figure S4, and the fitting parameters are outlined in

Table 7. The experimental data at different initial concentrations were again best described by the pseudo-second-order model. The

qe,cal obtained from this model agreed well with the

qe,exp. The

k2 was observed to decrease with increasing initial concentration. A higher initial concentration reduces mass transfer resistance from the bulk solution to the adsorbent surface, leading to more VOOEP and 1-MP molecules being adsorbed. However, at higher concentrations, the limited number of active sites on a fixed mass of PSA becomes saturated more quickly, leading to more intense competition for these sites, which may reflect as a decrease in the rate constant.

The effects of PSA dosage, temperature, and initial adsorbate concentration on the adsorption of VOOEP in the binary mixture system by PSA were consistent with the trends reported in the literature [

17,

39,

40] for the adsorption of single-component VOOEP on graphene and asphaltenes. The presence of 1-MP did not alter these trends.

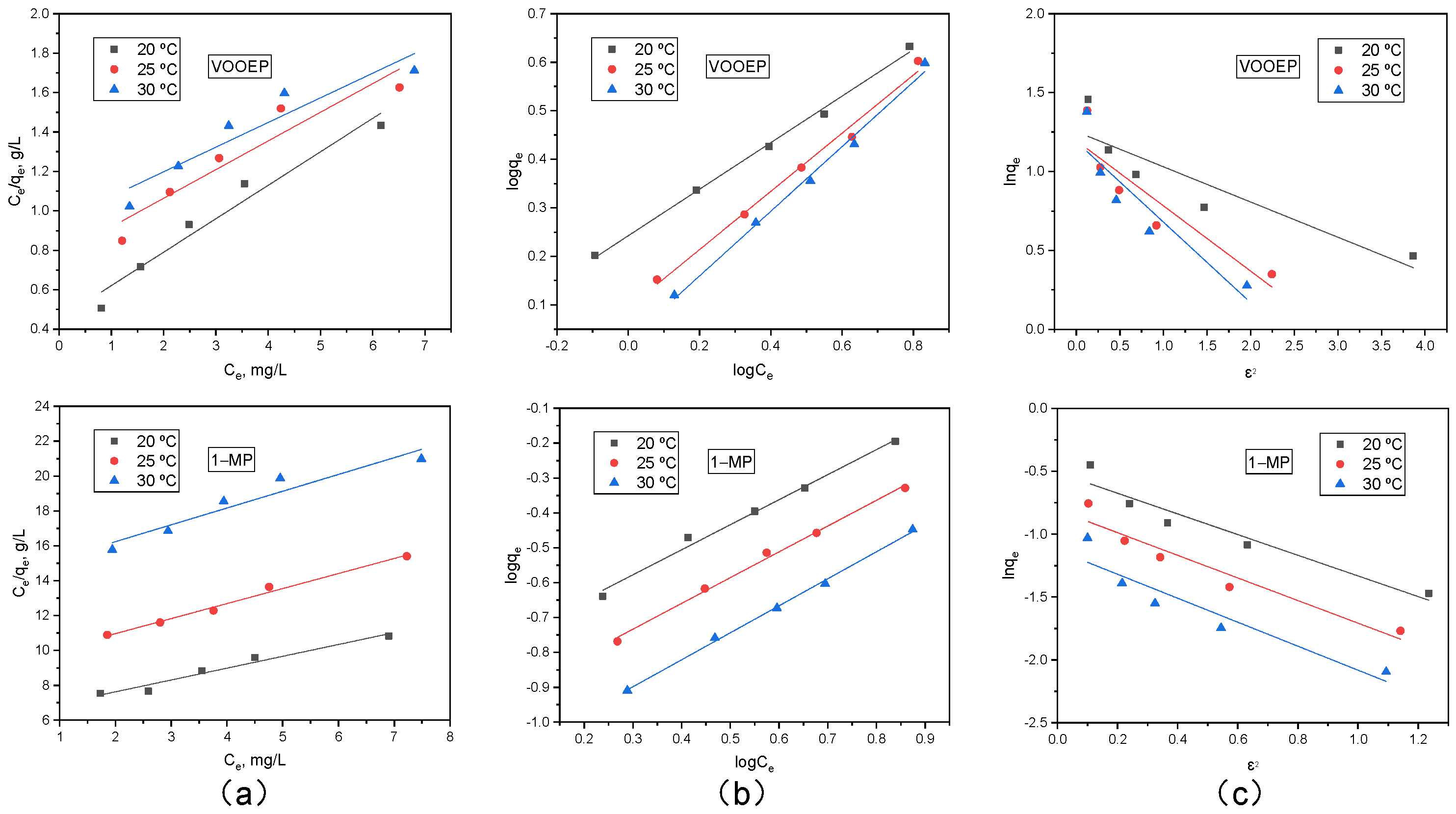

3.4. Adsorption Equilibrium and Isotherm Analysis

To gain deeper insight into the interaction between the adsorbates and PSA, the experimental data for VOOEP and 1-MP at three different temperatures (20, 25, 30 °C) were fitted using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) adsorption isotherm equations. The resulting fitting curves are presented in

Figure 9, with the corresponding parameters listed in

Table 8.

From

Figure 9 and

Table 8, it can be observed that at different temperatures, the Freundlich isotherm provided a better fit for the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA, exhibiting the highest correlation coefficients (R

2 > 0.99), compared to the Langmuir and D-R isotherms. This indicates that the adsorption isotherms of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA are better described by the Freundlich model, consistent with the adsorption results of asphaltenes for single metalloporphyrin components [

39,

40]. The good fit of the experimental data to the Freundlich isotherm suggests that PSA has a heterogeneous surface, and the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA is not uniform monolayer adsorption but also involves multilayer adsorption.

The Freundlich model parameters

KF and 1/

n are indicative of adsorption capacity and intensity, respectively [

35]. The

KF value for VOOEP was consistently and significantly higher than that for 1-MP at any given temperature, indicating PSA’s greater affinity and capacity for VOOEP [

41]. This is mainly attributed to the strong axial coordination between the amine functional groups on the PSA surface and V

4+ in VOOEP [

22]. For both compounds,

KF values decreased with increasing temperature, reconfirming the exothermic nature of the adsorption process and the lower adsorption capacity at higher temperatures. The parameter 1/

n is a measure of the adsorption intensity or the adsorbent surface heterogeneity. A value below unity indicates a chemisorption process [

35]. A smaller 1/

n value means more favorable adsorption. The 1/

n values for both VOOEP and 1-MP were less than 1 and increased with temperature, suggesting that the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA is a chemisorption process, and higher temperatures are less favorable for the adsorption.

Although the D-R isotherm fitting results were not as good as the Freundlich isotherm, the D-R parameter

E value can be used to estimate the type of adsorption. For all temperatures and both adsorbates, the

E values were less than 8 kJ/mol (ranging from 0.72 to 1.50 kJ/mol). According to the literature, [

42,

43] the

E values less than 8 kJ/mol are characteristic of physical adsorption governed by weak forces such as van der Waals interactions or hydrogen bonding. Values between 8 and 16 kJ/mol suggest ion-exchange mechanisms.

The E values here point towards a physical adsorption process. This seems to contradict the Freundlich isotherm and the kinetic results, which favored the pseudo-second-order (chemisorption) model. This apparent contradiction can be resolved by considering the nature of the interaction. The coordination bond between the amine group and the V4+ ion, while strong and specific, did not involve full covalent bond formation as in classic chemisorption. It can be considered a strong physical interaction or a coordinative physical adsorption. The energy associated with this interaction was classified as physical adsorption by the D-R isotherm criterion.

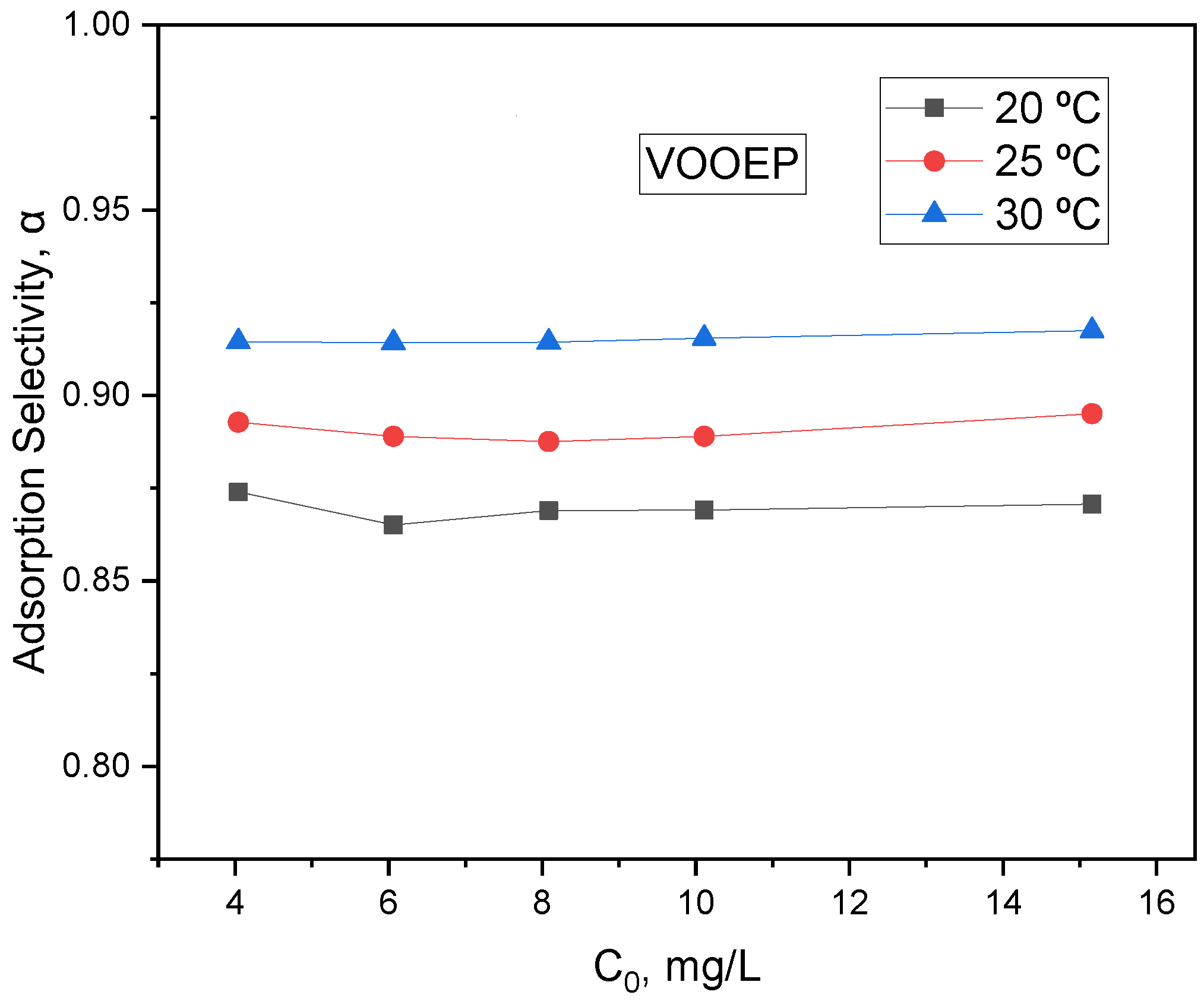

For the adsorption of metalloporphyrins on PSA, besides adsorption capacity, adsorption selectivity is also an important indicator.

Figure 10 shows the adsorption selectivity of PSA for VOOEP at different temperatures. It can be seen that the selectivity (α) of PSA for VOOEP relative to 1-MP actually increases with increasing temperature. Higher temperatures favor the selective adsorption of VOOEP on PSA. However, the adsorption capacity for VOOEP decreases with increasing temperature (due to exothermicity); thus, higher temperatures are unfavorable for VOOEP adsorption. Therefore, for the adsorption of metalloporphyrins in real samples, both adsorption capacity and selectivity should be considered to determine the appropriate adsorption temperature and other conditions.

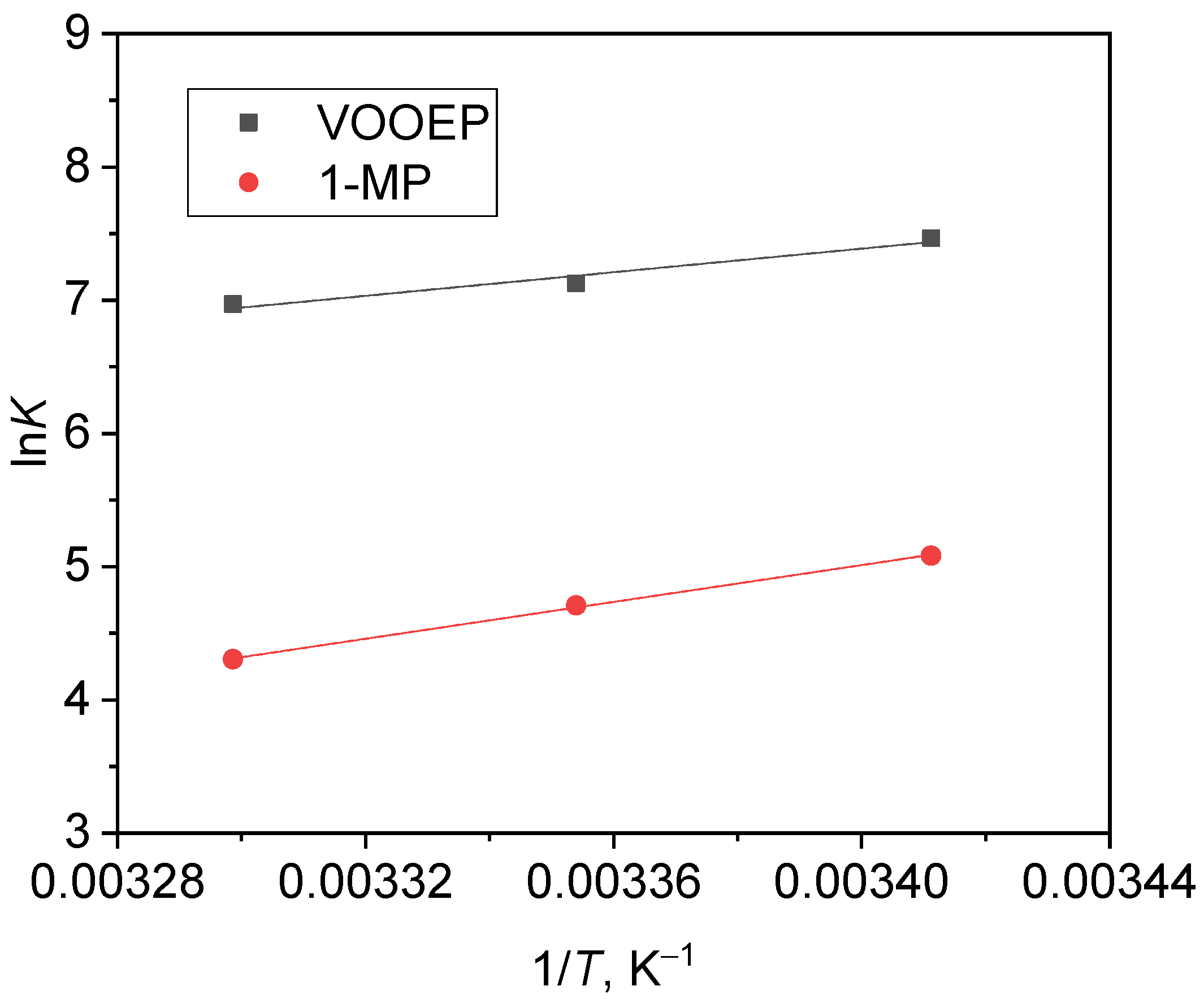

3.5. Adsorption Thermodynamics Study

The corresponding ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS values were calculated based on the Freundlich isotherm parameter

KF at different temperatures and the Equations listed in

Table 4. The plots of ln

K versus 1/

T and the obtained thermodynamic parameters are given in

Figure 11 and

Table 9.

The values of ΔG for the adsorption of both VOOEP and 1-MP onto PSA were negative at all temperatures studied, confirming that the process is spontaneous and thermodynamically favorable. The magnitude of ΔG became less negative as the temperature increased, indicating that the spontaneity decreases with rising temperature, which shows that lower temperatures are more favorable for adsorption. Furthermore, the ΔG values for VOOEP were more negative than those for 1-MP at each corresponding temperature. This verifies that the adsorption of VOOEP on PSA is more spontaneous and favorable than that of 1-MP, directly explaining the observed selectivity. The ΔS values for VOOEP and 1-MP were all negative, indicating the decrease in randomness at the solid-solution interface during the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA.

The negative values of ΔH suggest that the adsorption of both VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA is an exothermic process. The absolute value of ΔH for the adsorption of 1-MP on PSA was higher than that for VOOEP, indicating that more heat is released during the adsorption of 1-MP on PSA. The absolute value of ΔH can be used to infer whether the adsorption is physical or chemical. Physical adsorption is caused by weak interactions, including electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, charge transfer, etc. Chemical adsorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between the adsorbent and adsorbate, typically covalent bonds [

44]. The magnitude of the ΔH value for physical adsorption generally ranges from 2.1 to 20.9 kJ/mol, while for chemical adsorption it ranges from 80 to 200 kJ/mol [

32,

45]. The absolute values of ΔH for VOOEP and 1-MP were less than 80 kJ/mol, indicating that the adsorption of VOOEP and 1-MP on PSA does not involve chemical bond formation, and the process is physical adsorption. This adsorption process may involve a combination of forces such as hydrogen bonding (adsorption heat range: 2–40 kJ/mol), dipole–dipole forces (2–29 kJ/mol), and coordination bond exchange (~40 kJ/mol) [

44]. This is consistent with the conclusion from the D-R isotherm model.