C–H Annulation in Azines to Obtain 6,5-Fused-Bicyclic Heteroaromatic Cores for Drug Discovery

Abstract

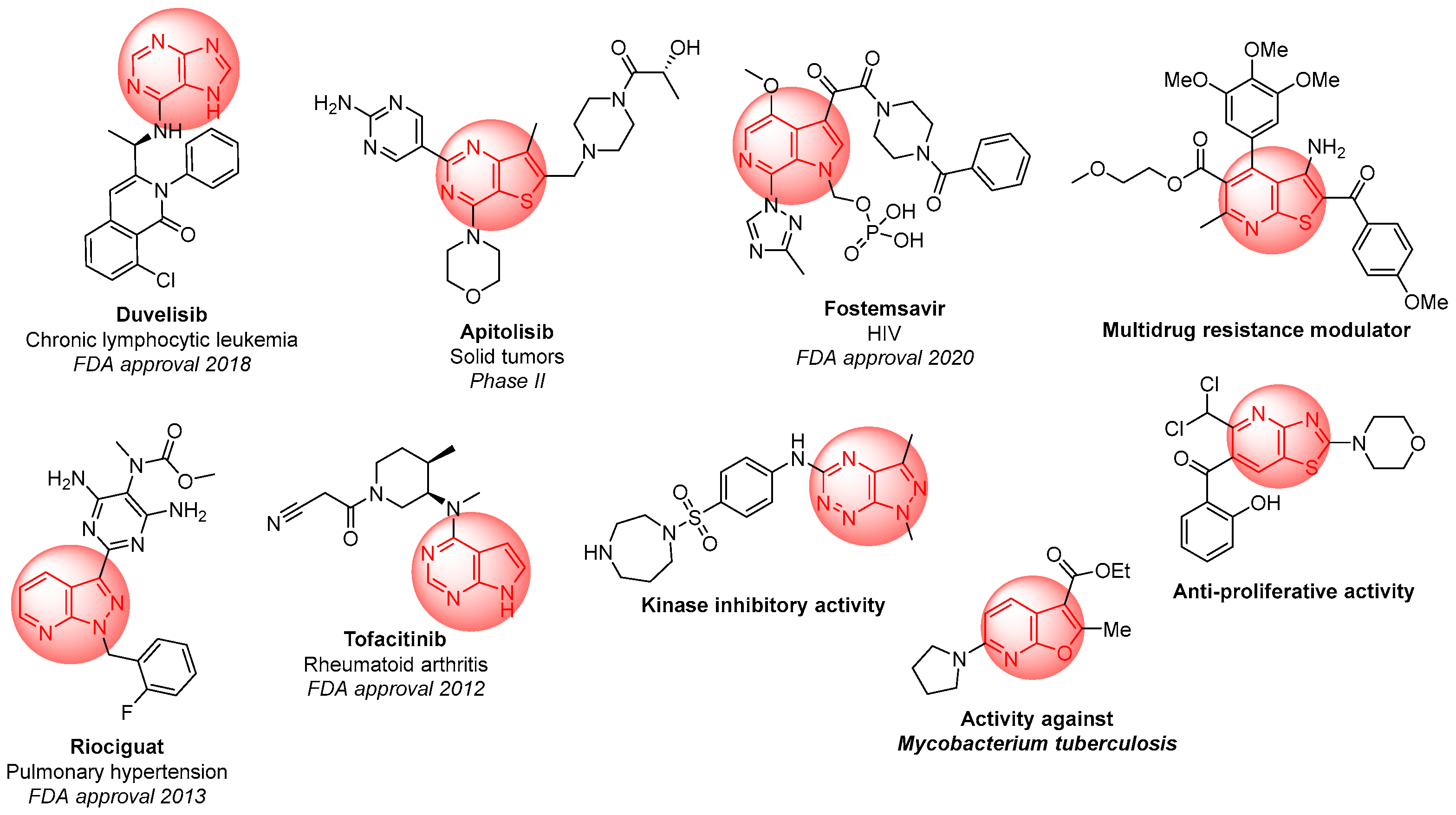

1. Introduction

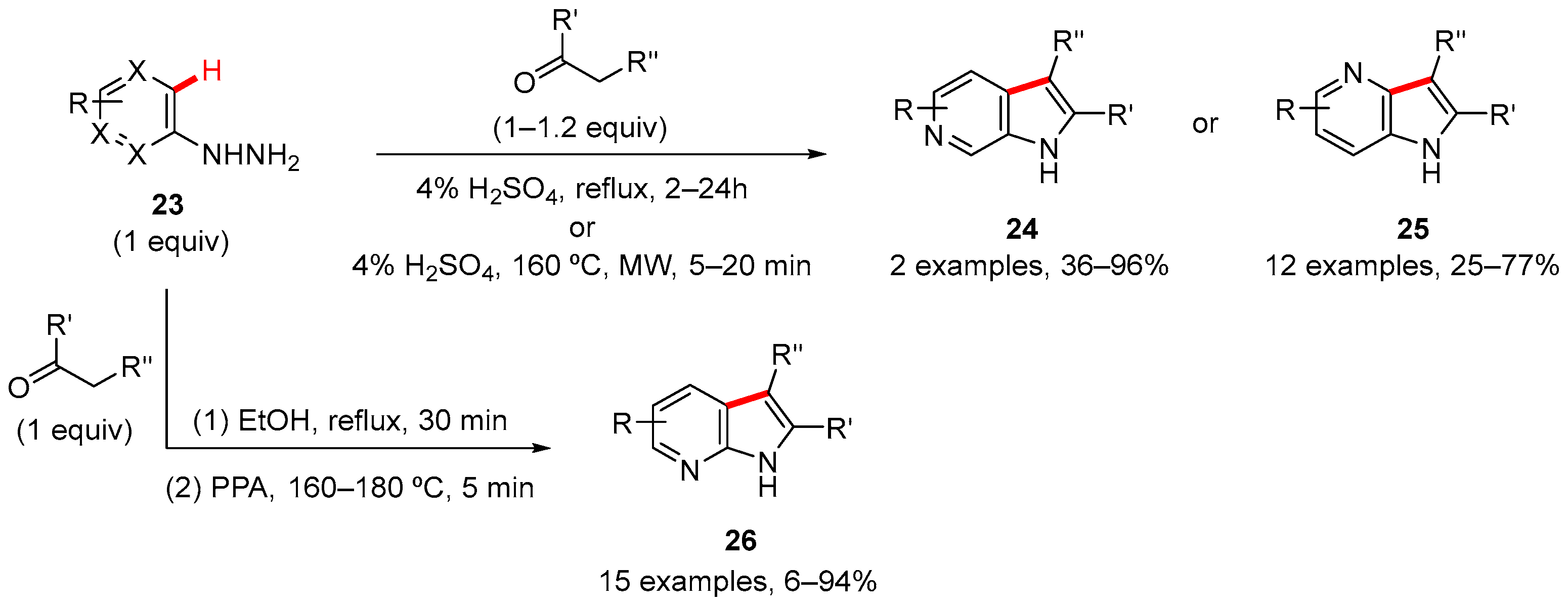

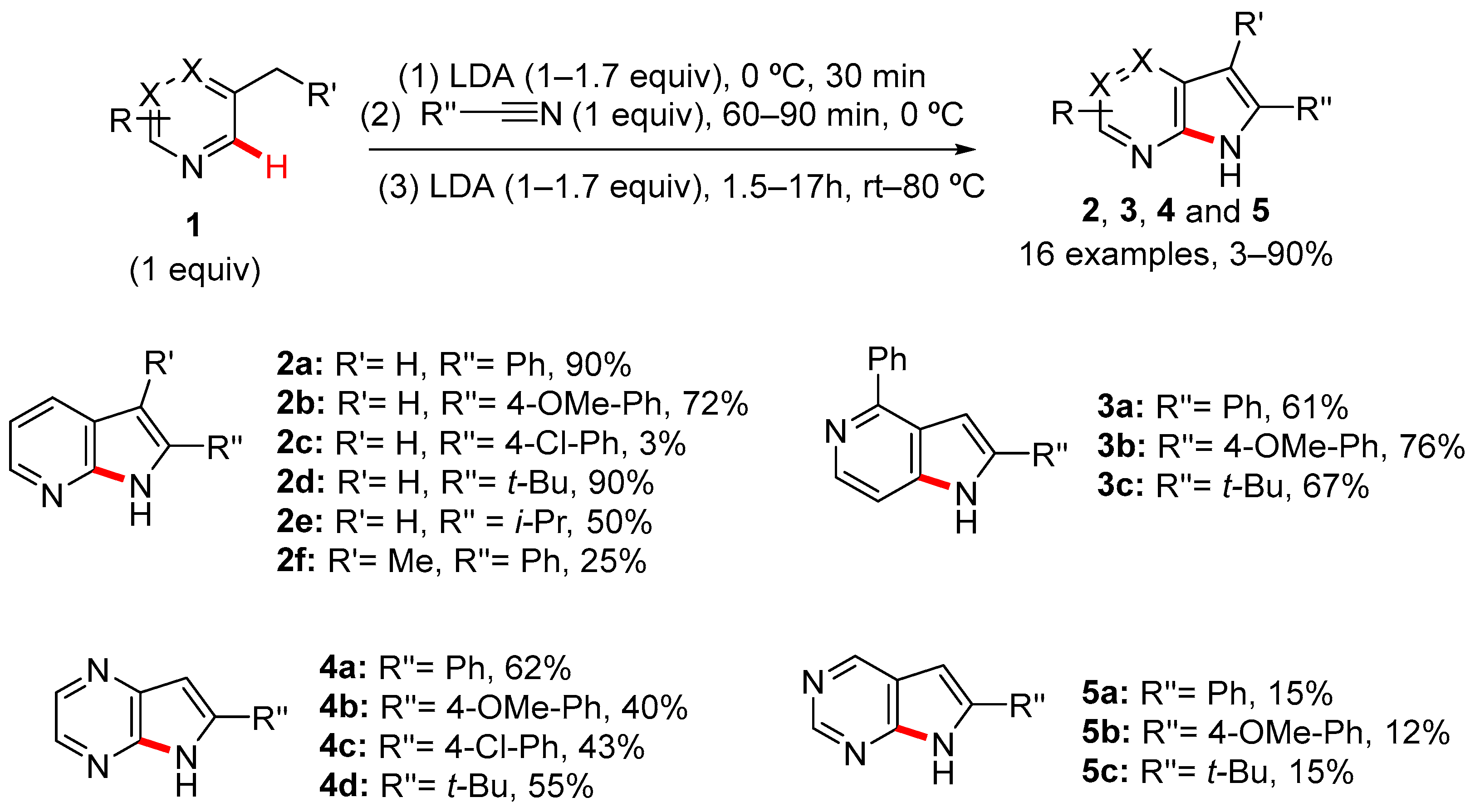

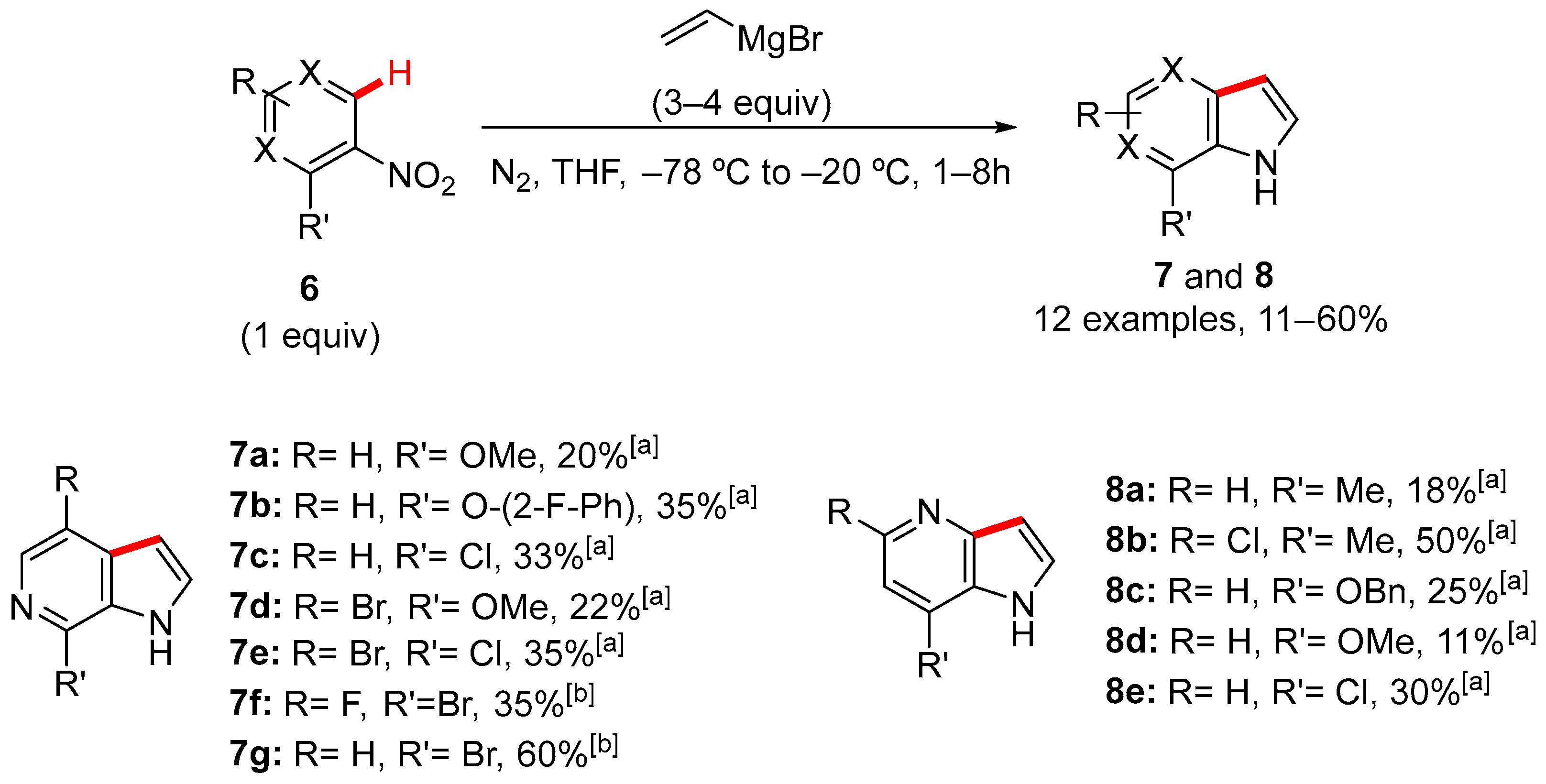

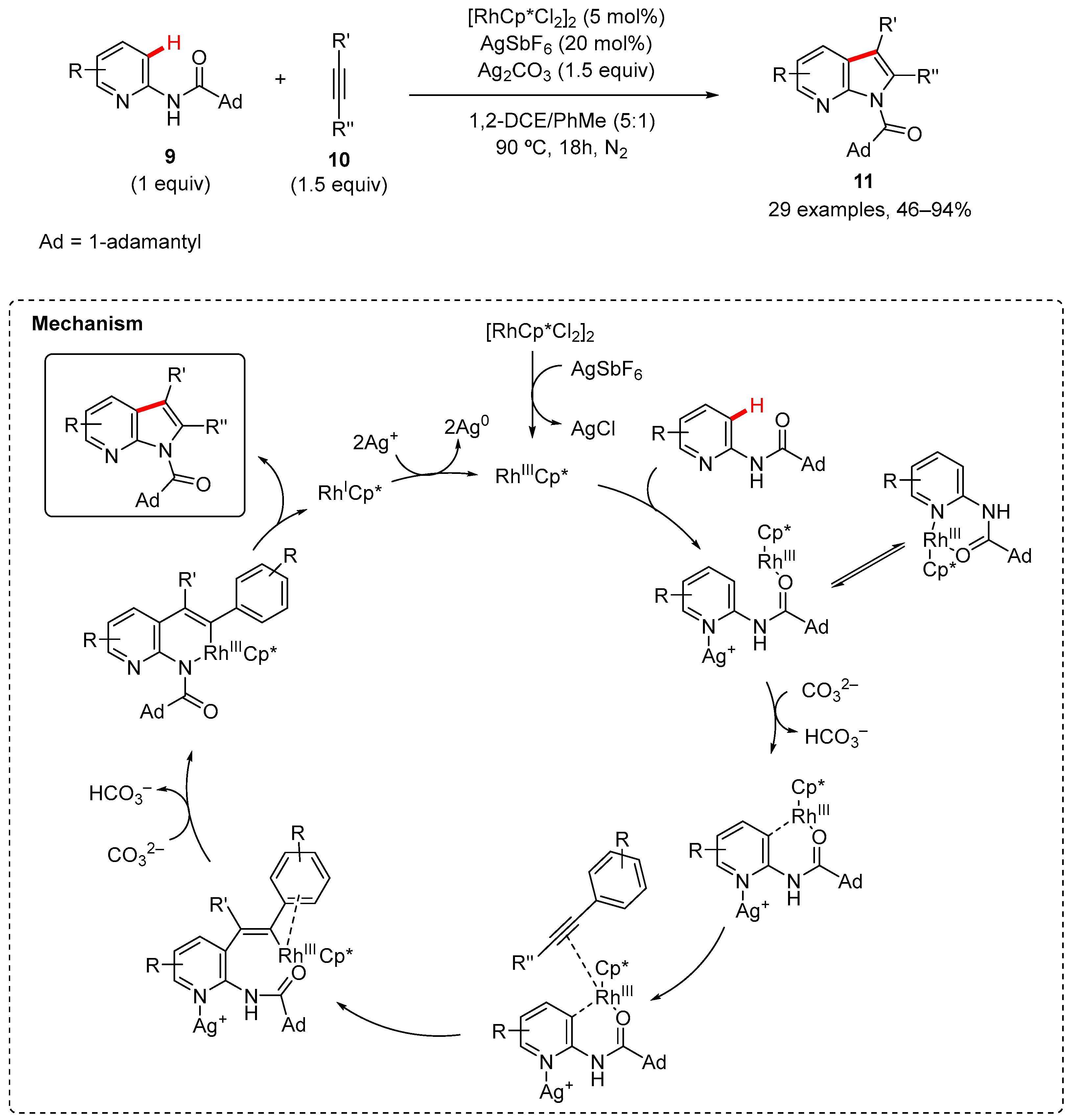

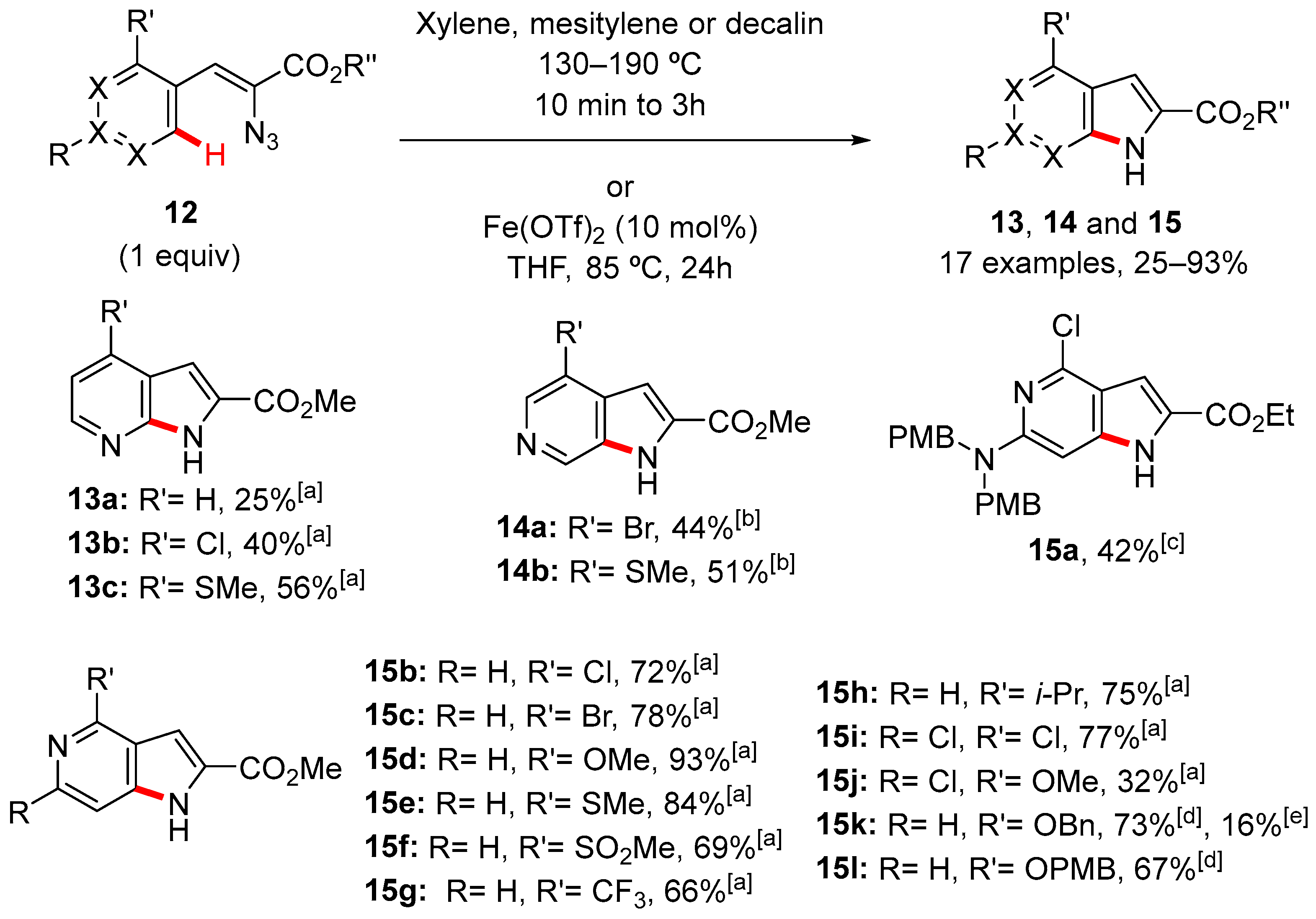

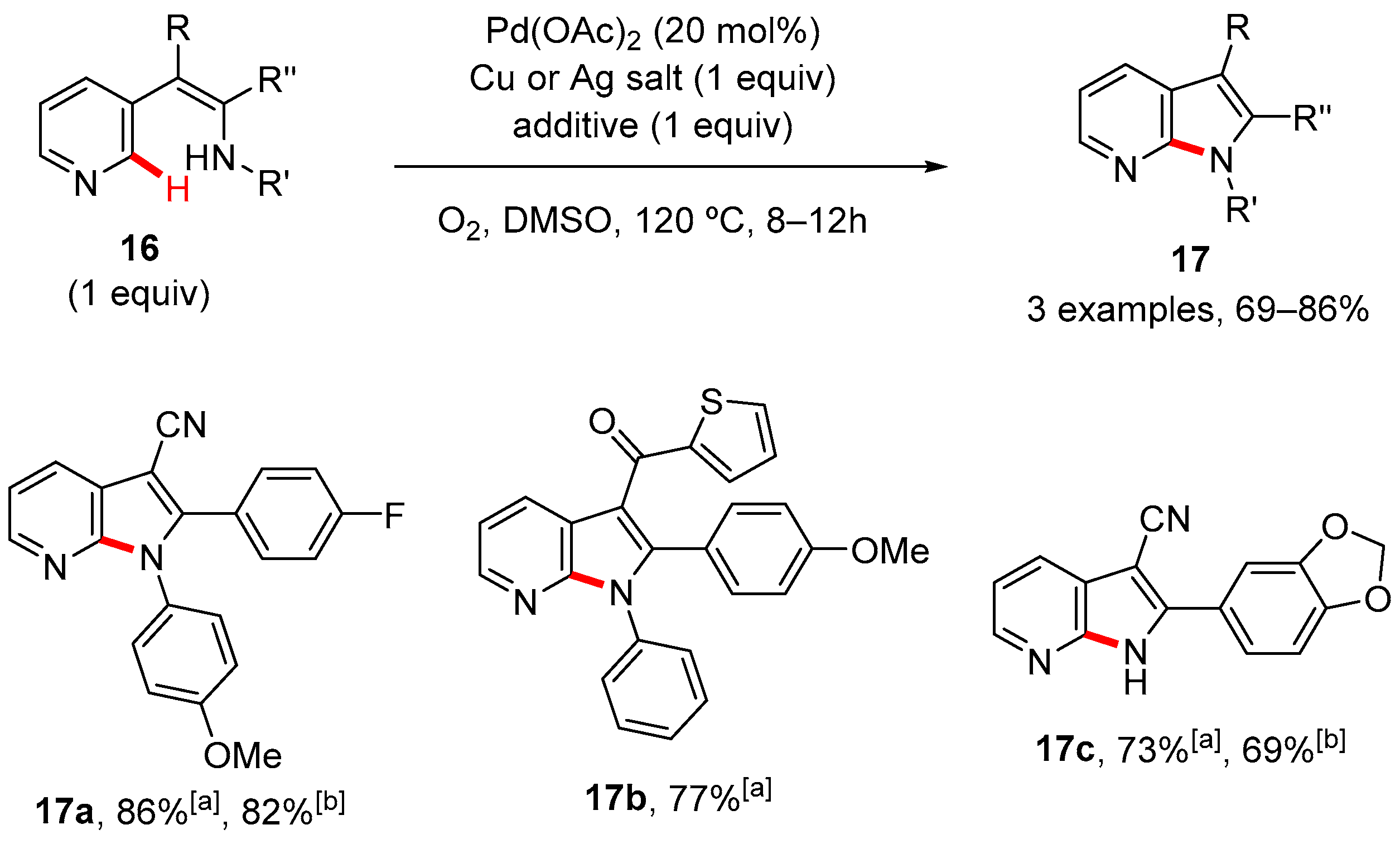

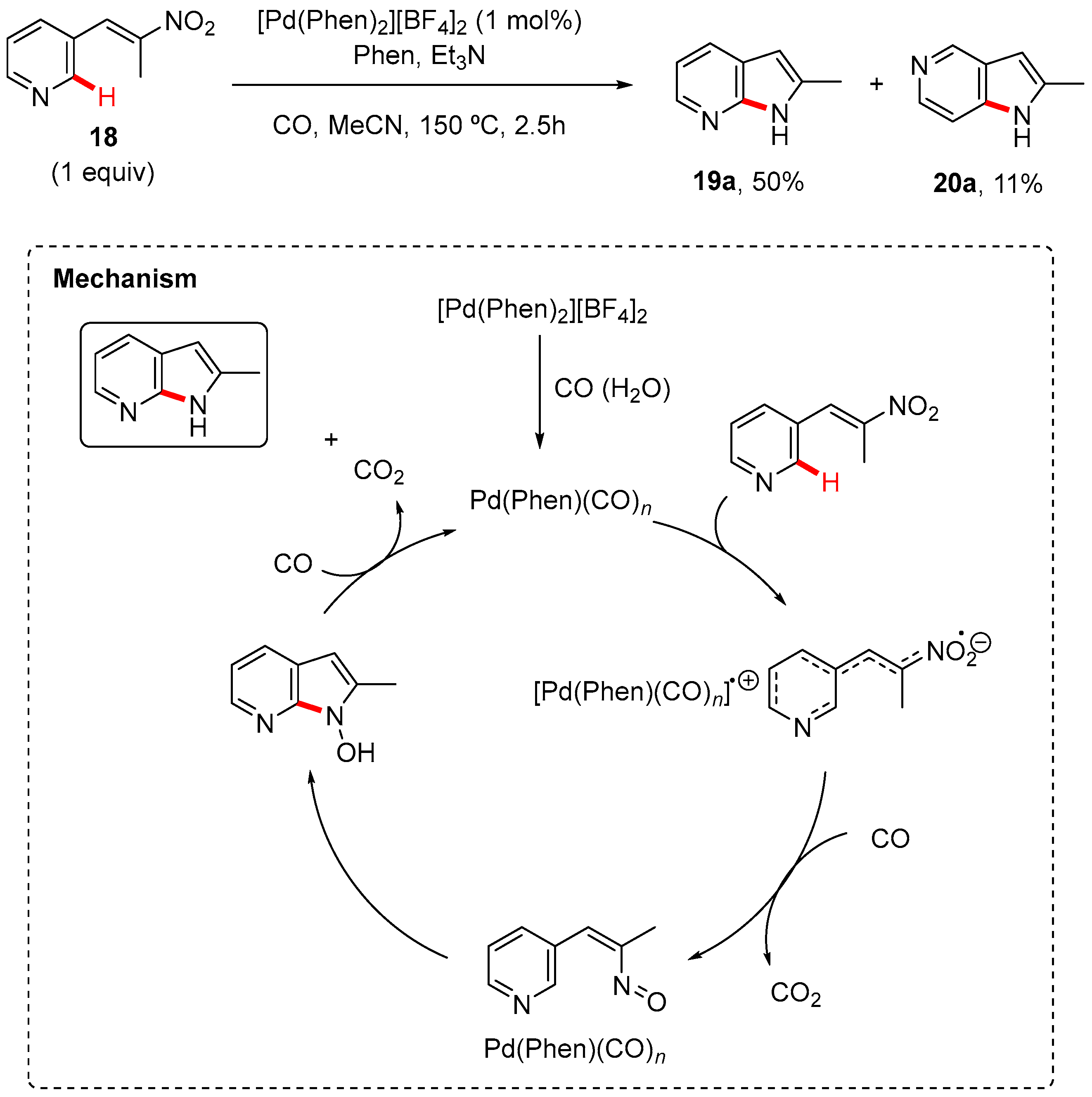

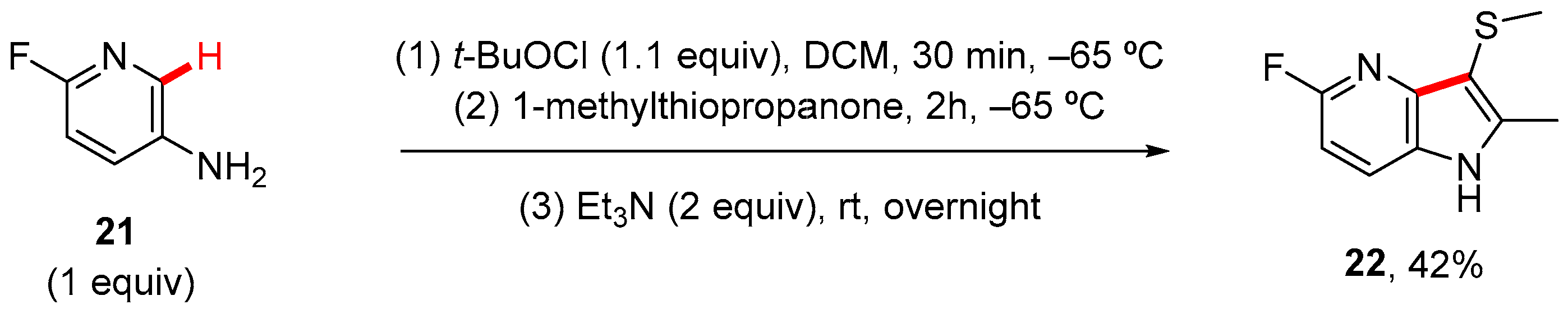

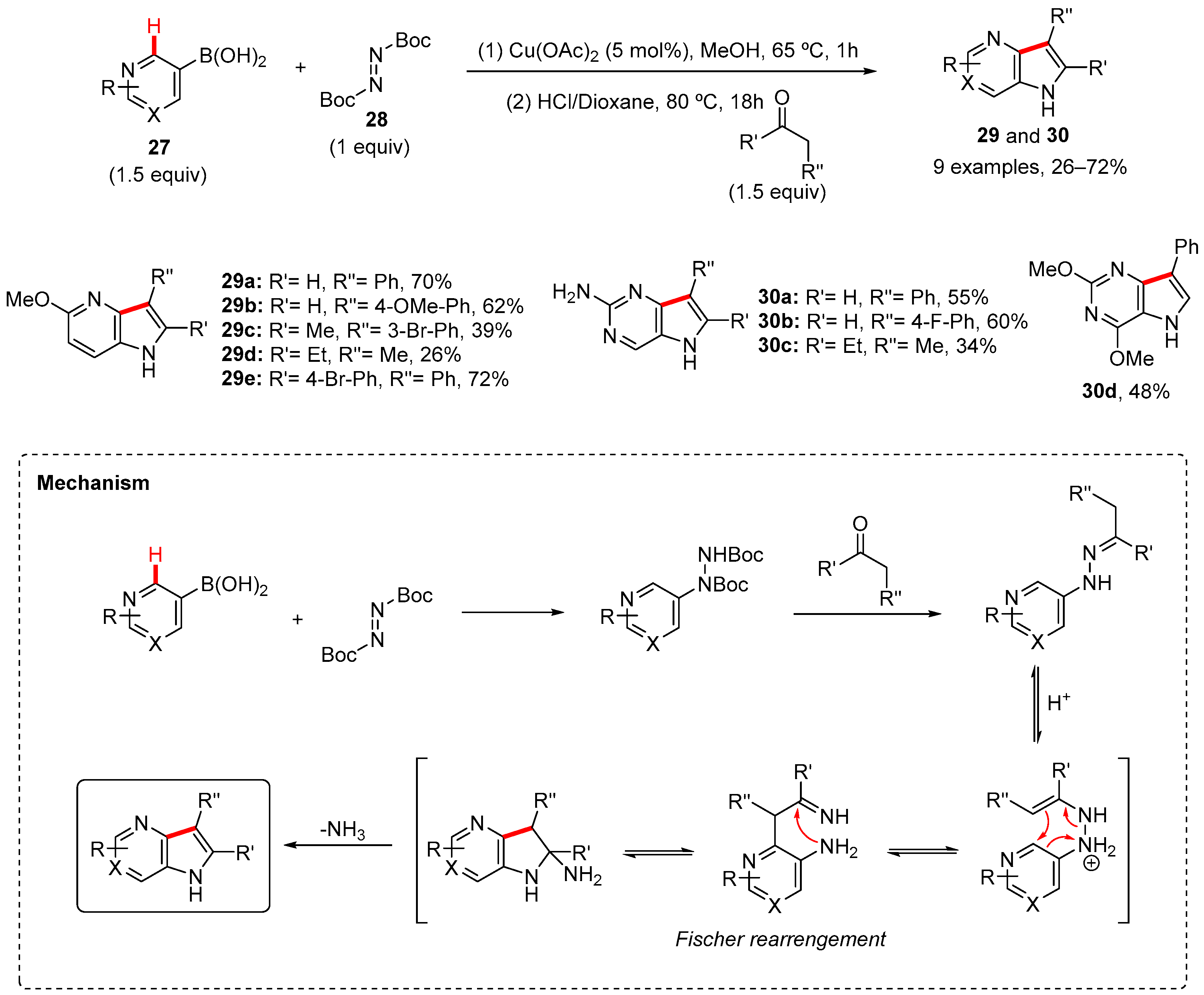

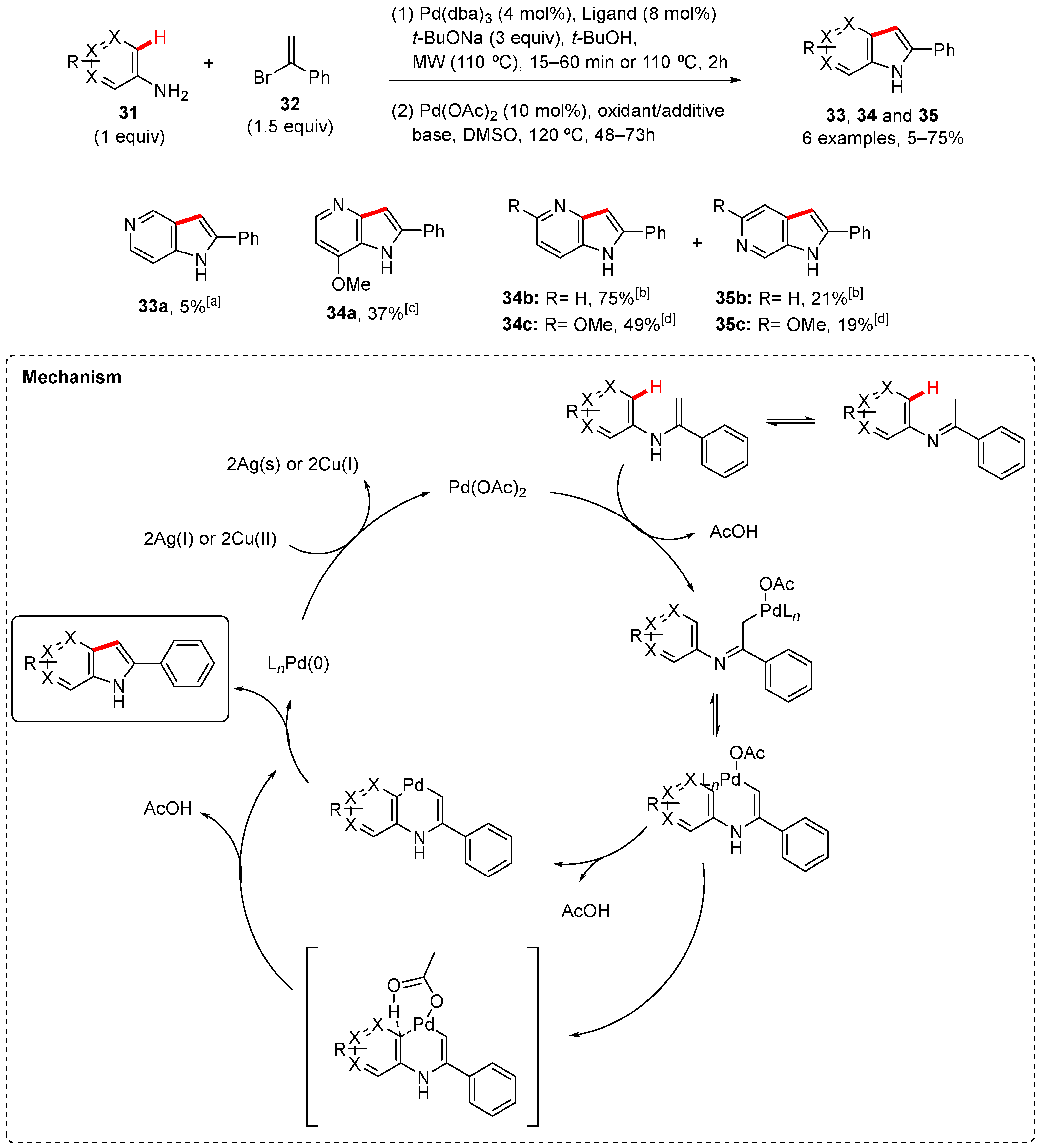

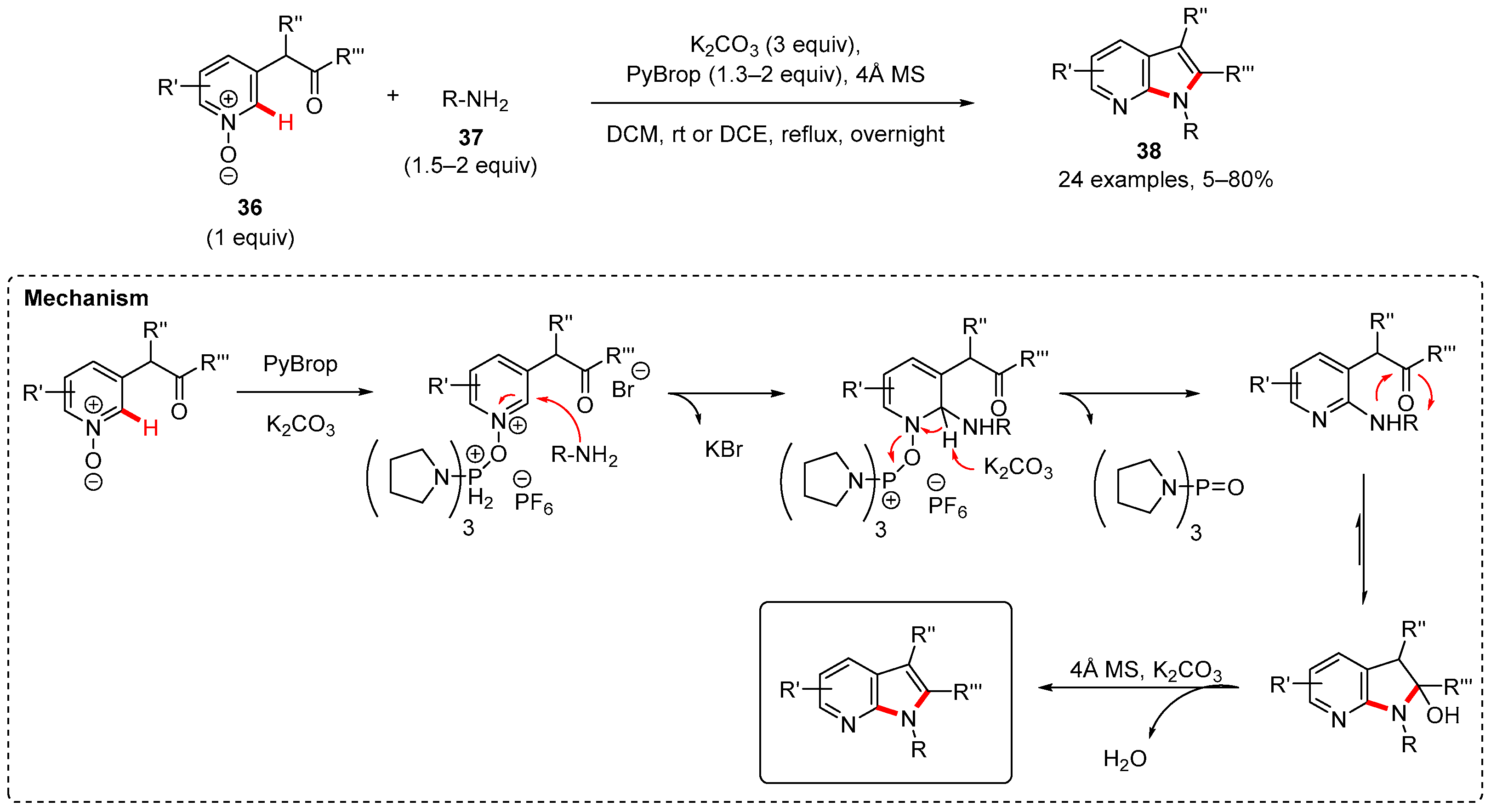

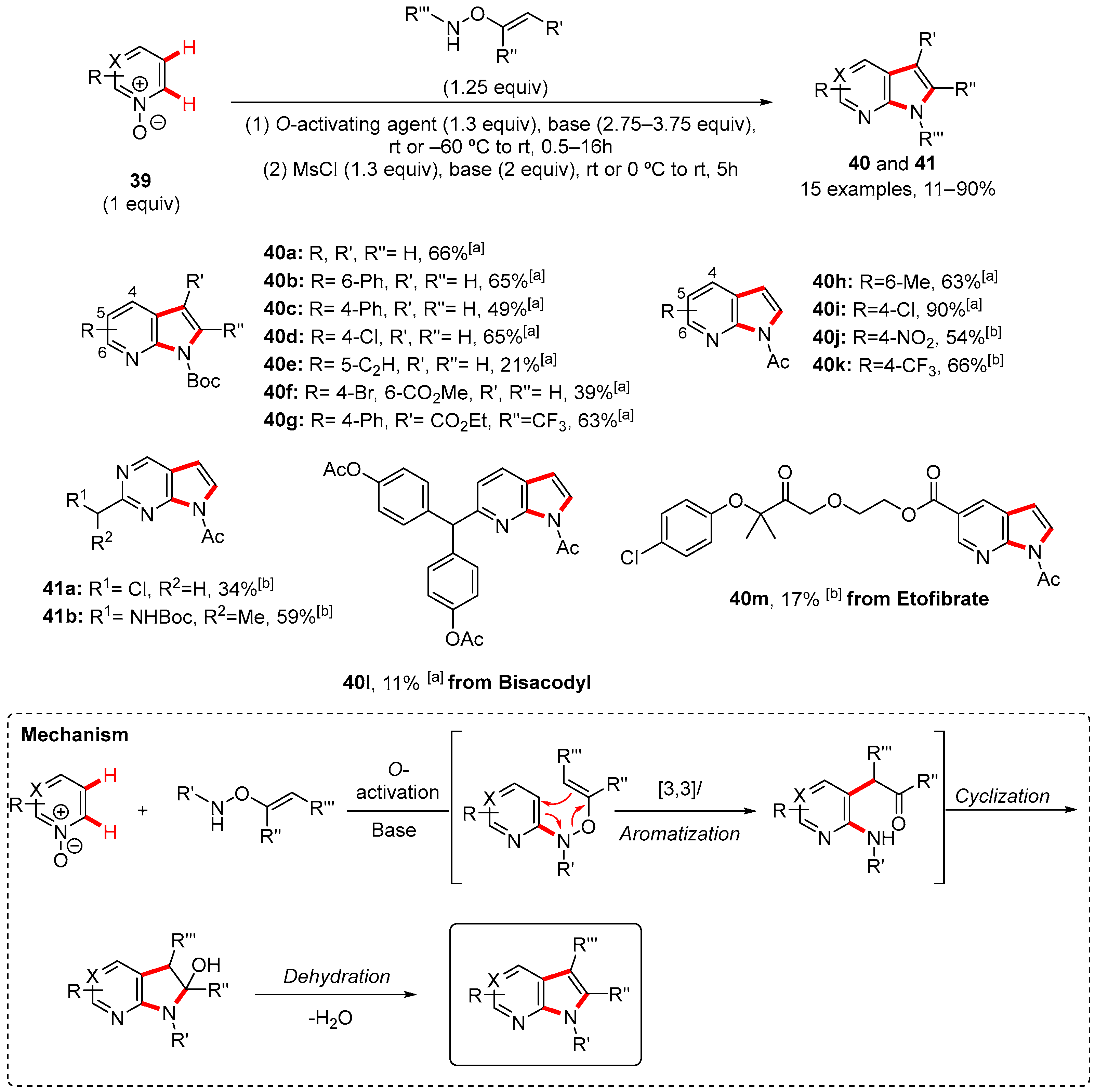

2. Pyrrole-Fused to Azines

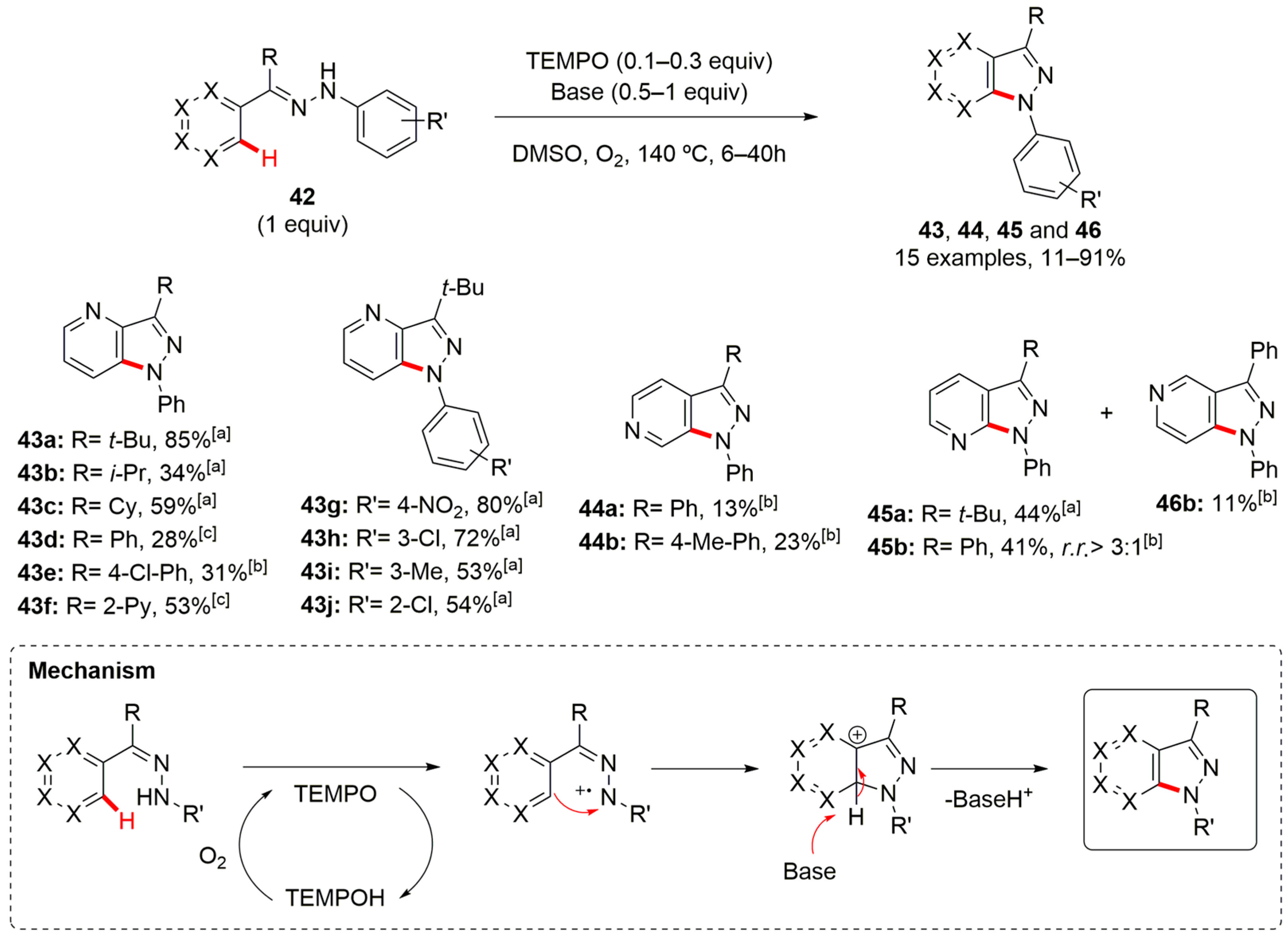

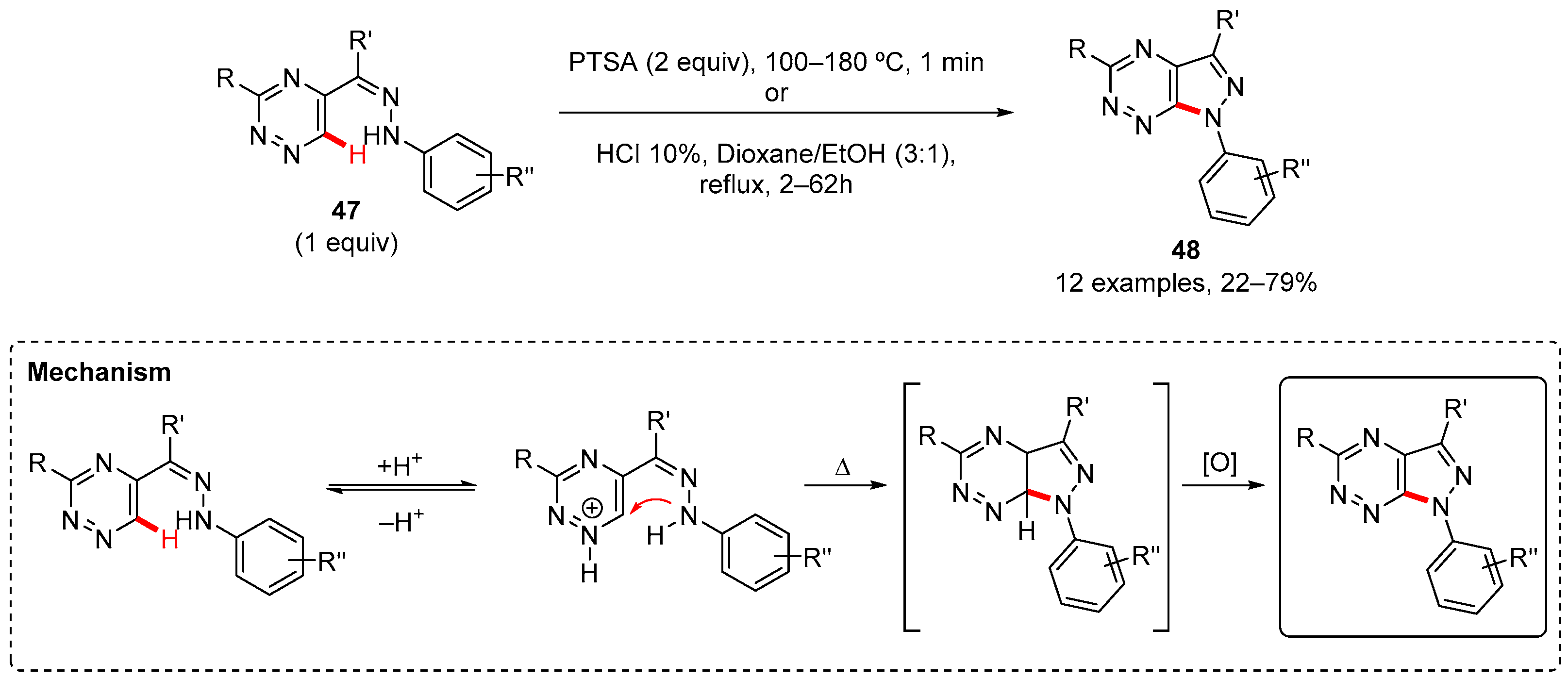

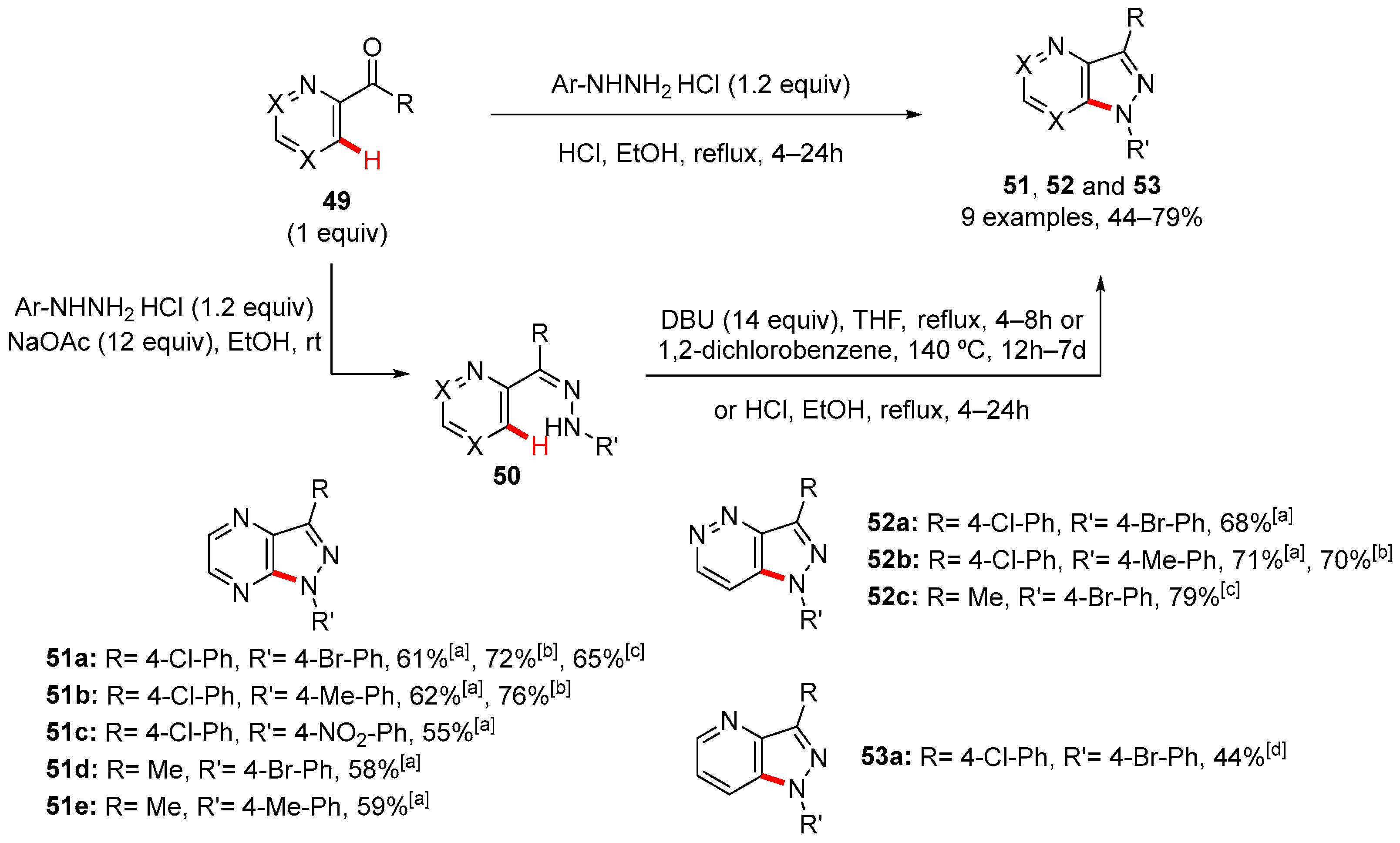

3. Pyrazole-Fused to Azines

4. Imidazole-Fused to Azines

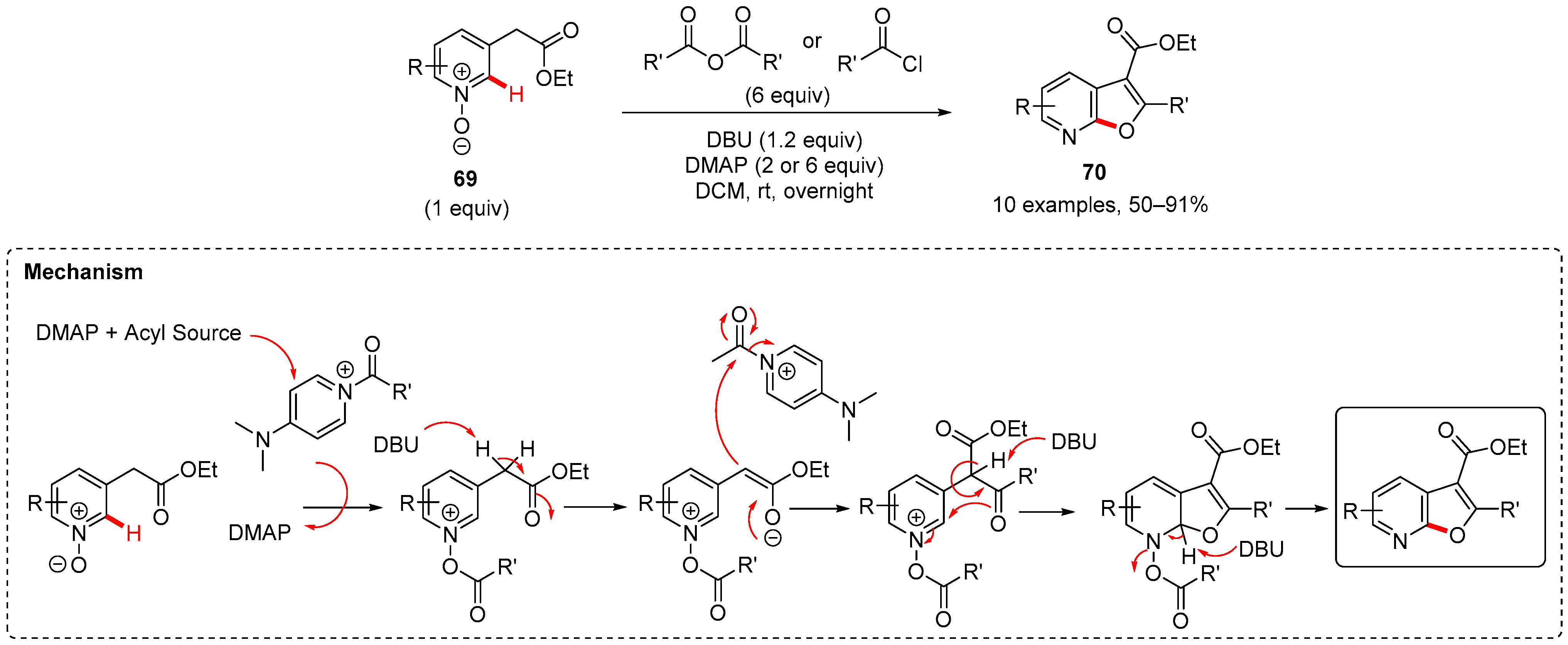

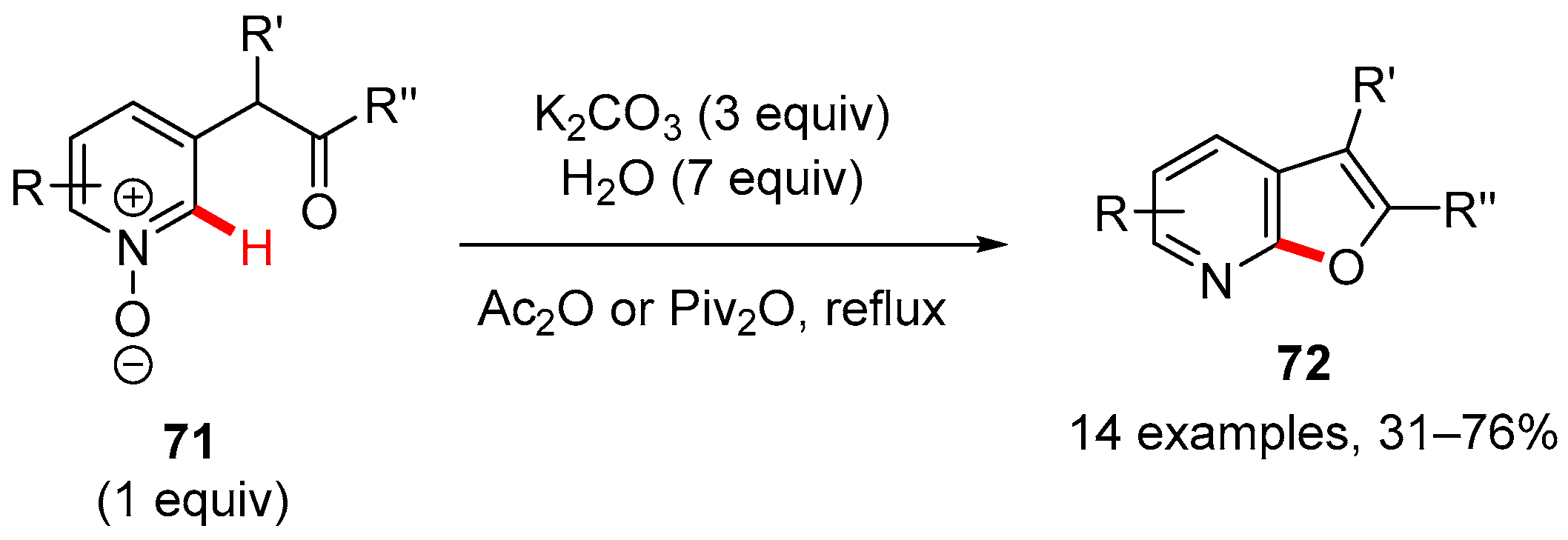

5. Furan-Fused to Azines

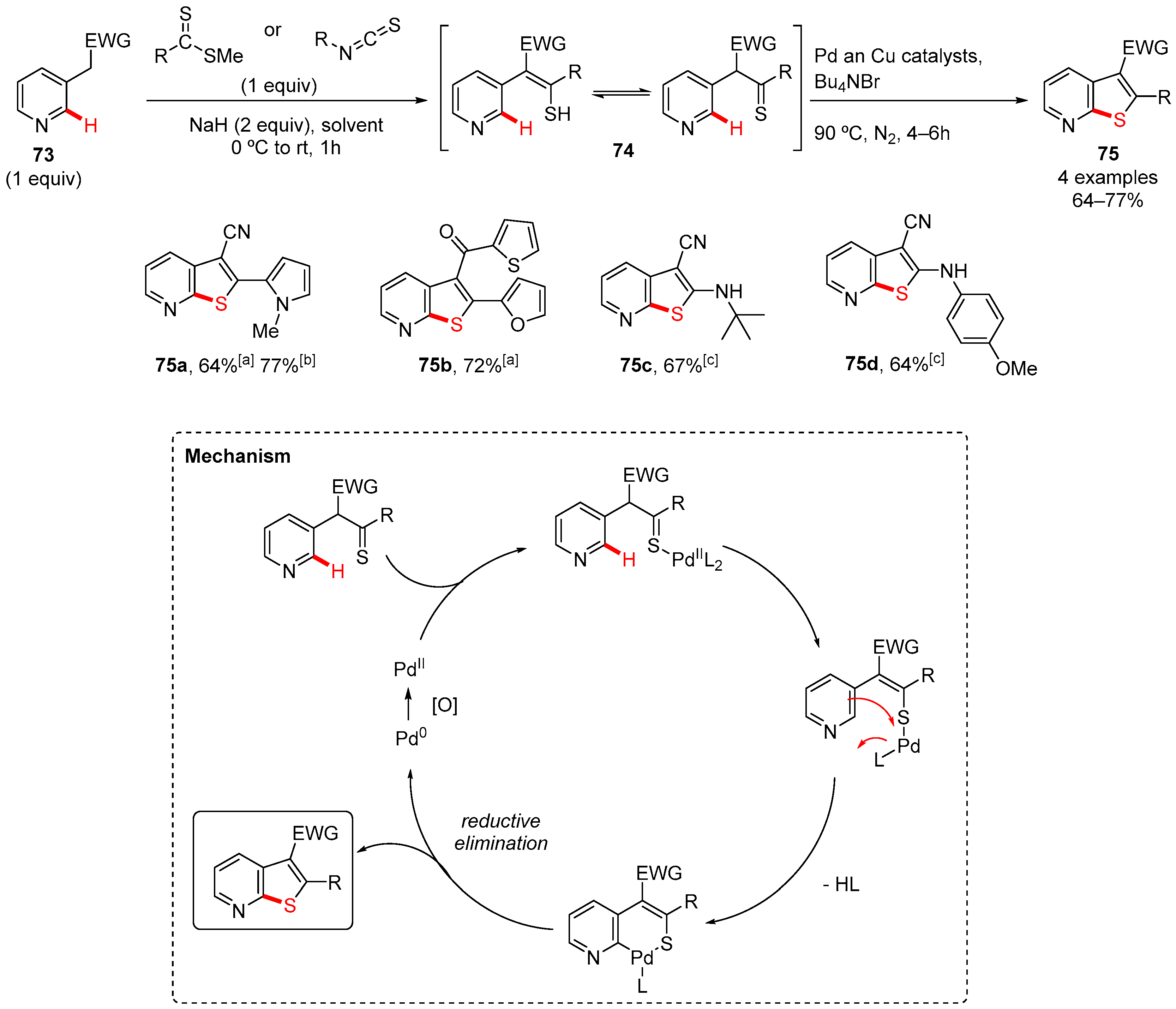

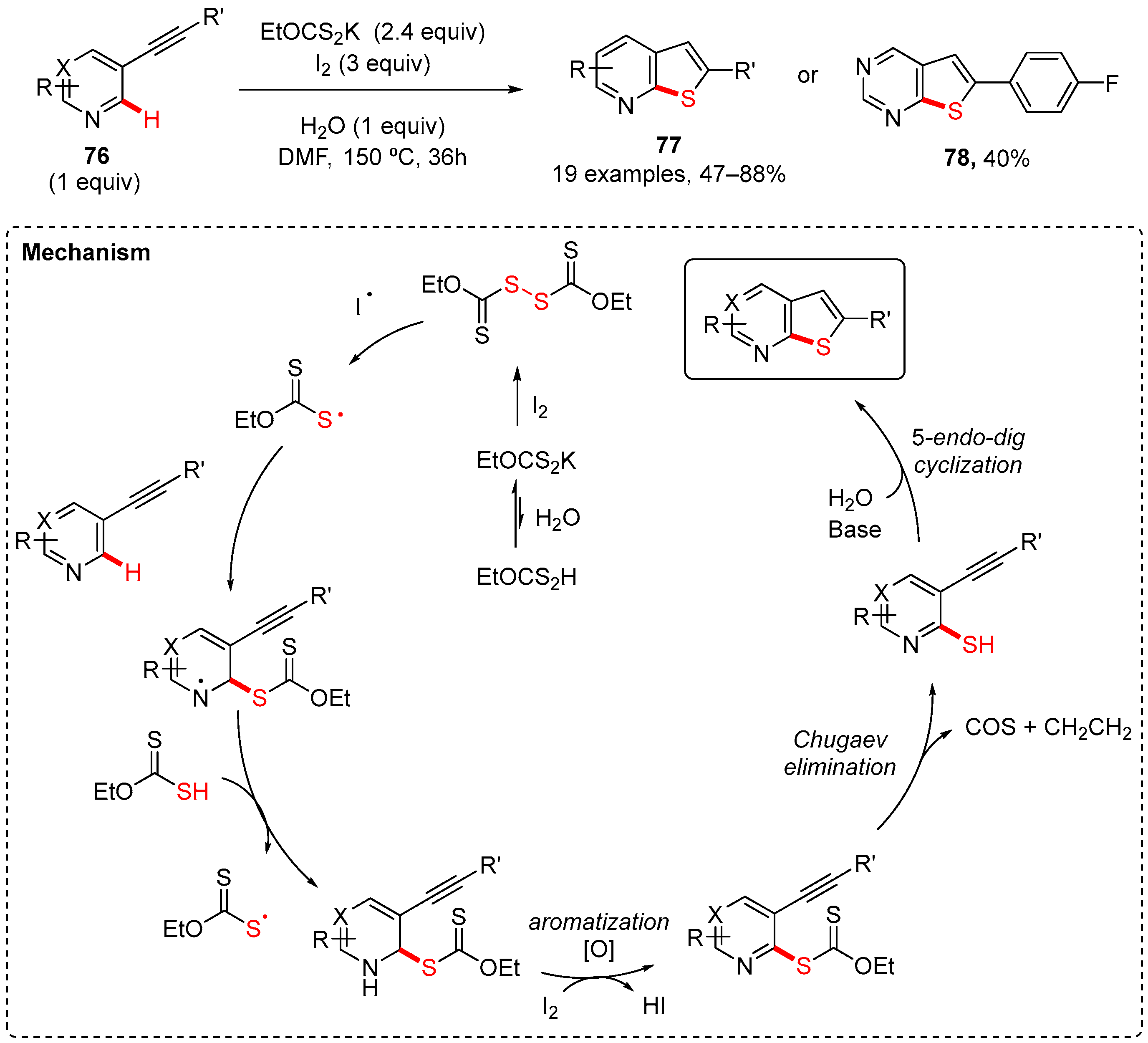

6. Thiophen-Fused to Azines

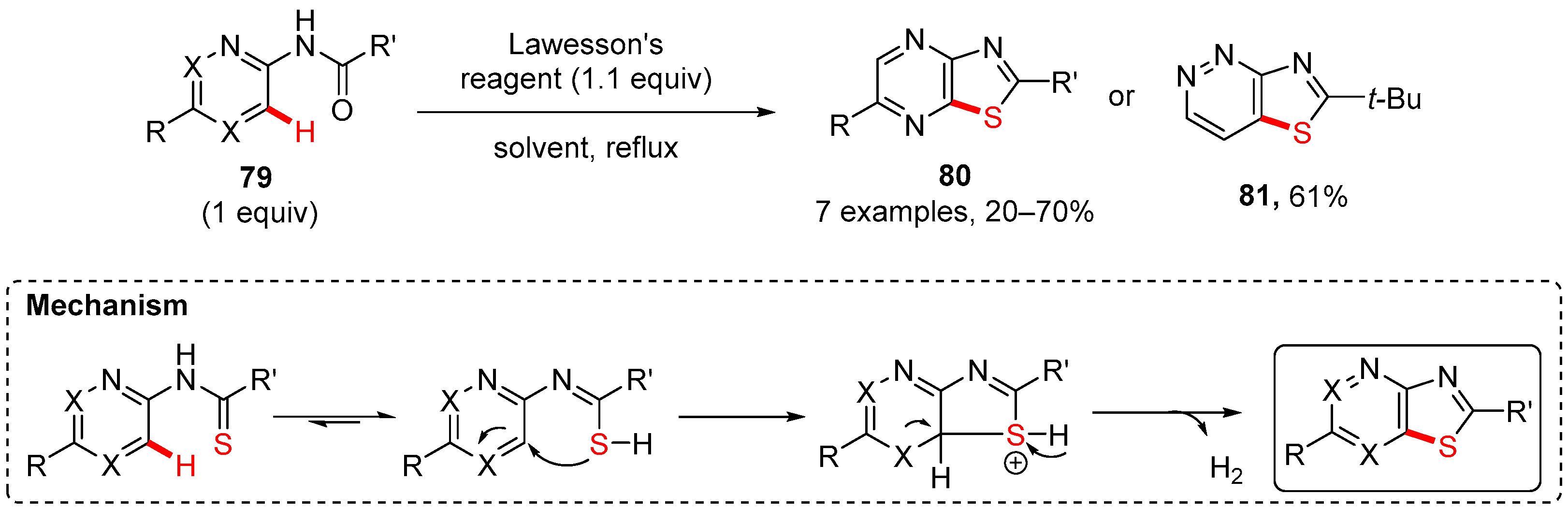

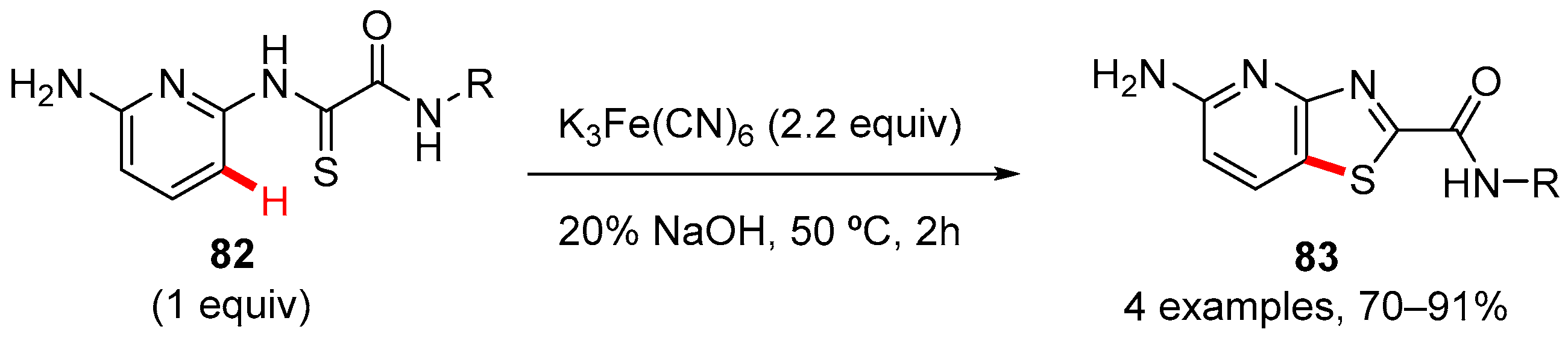

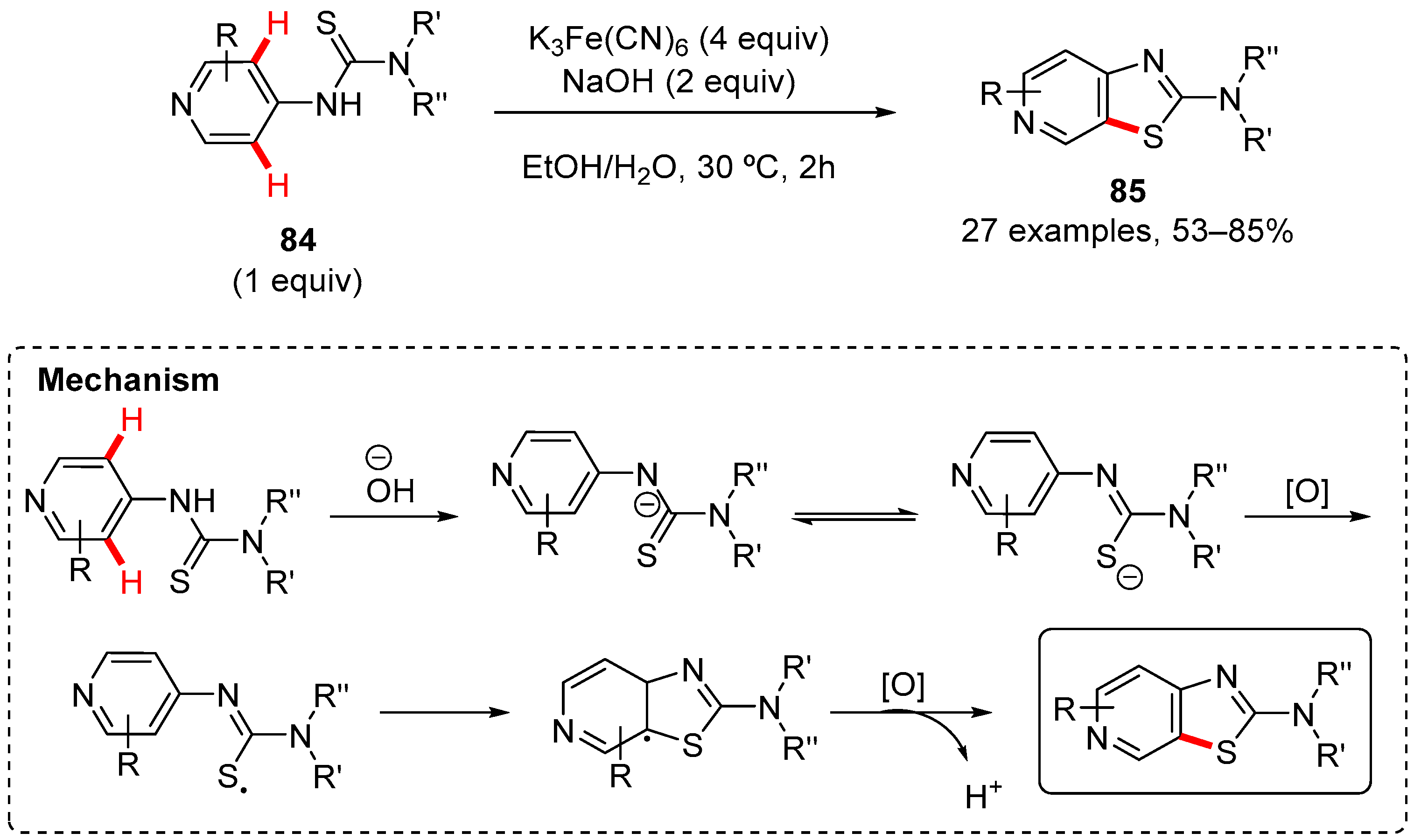

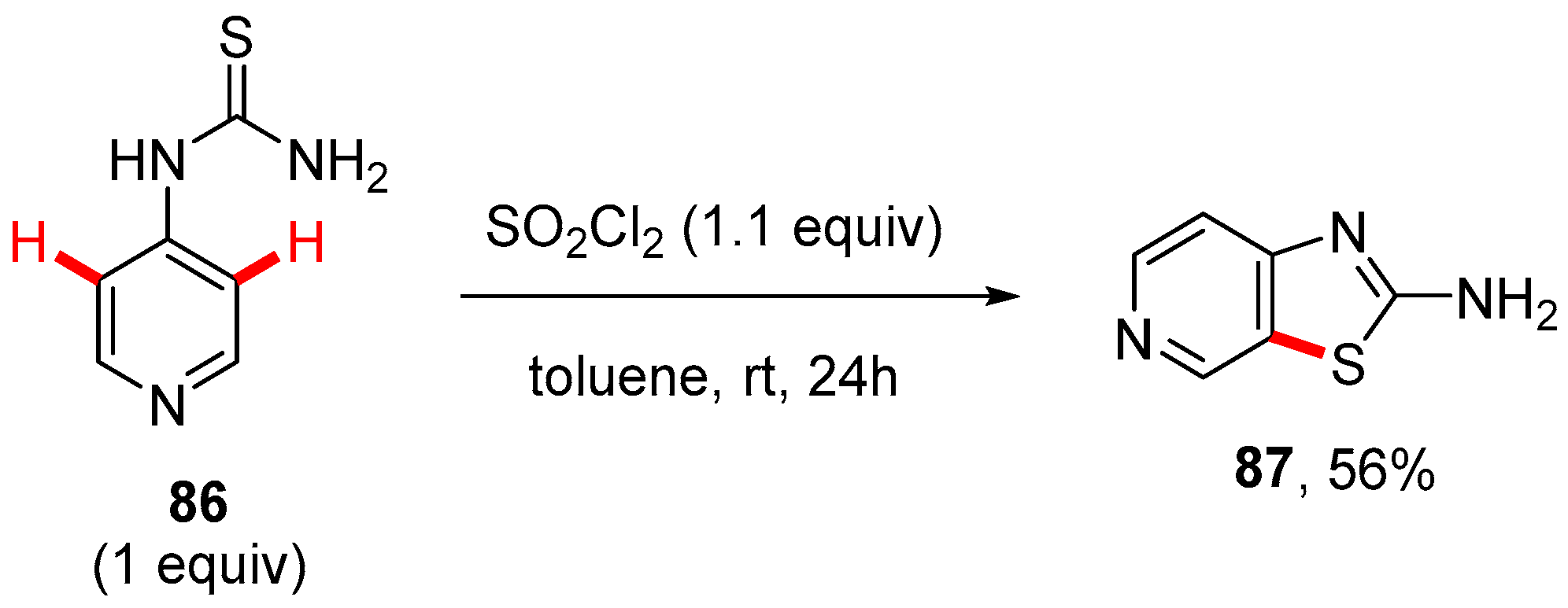

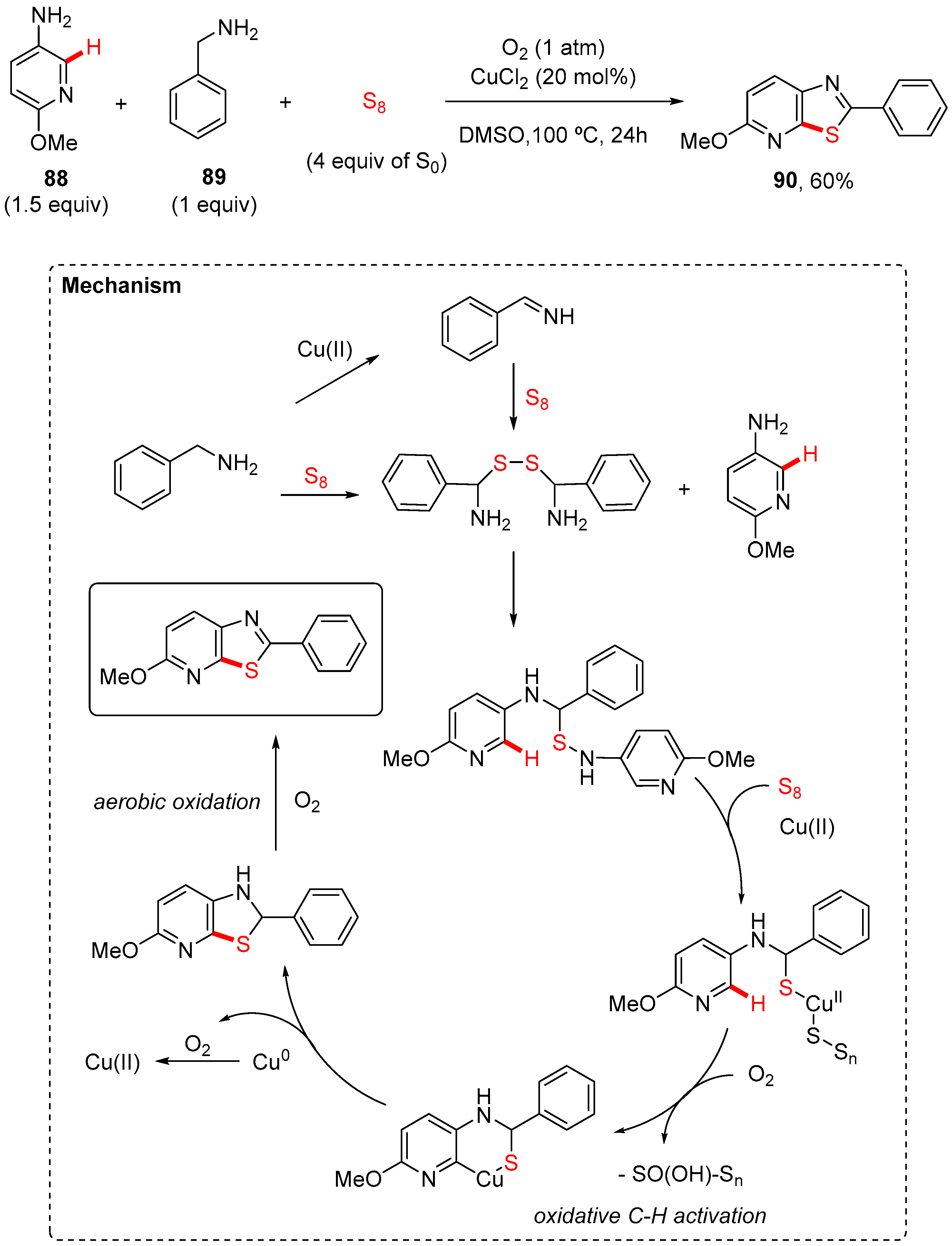

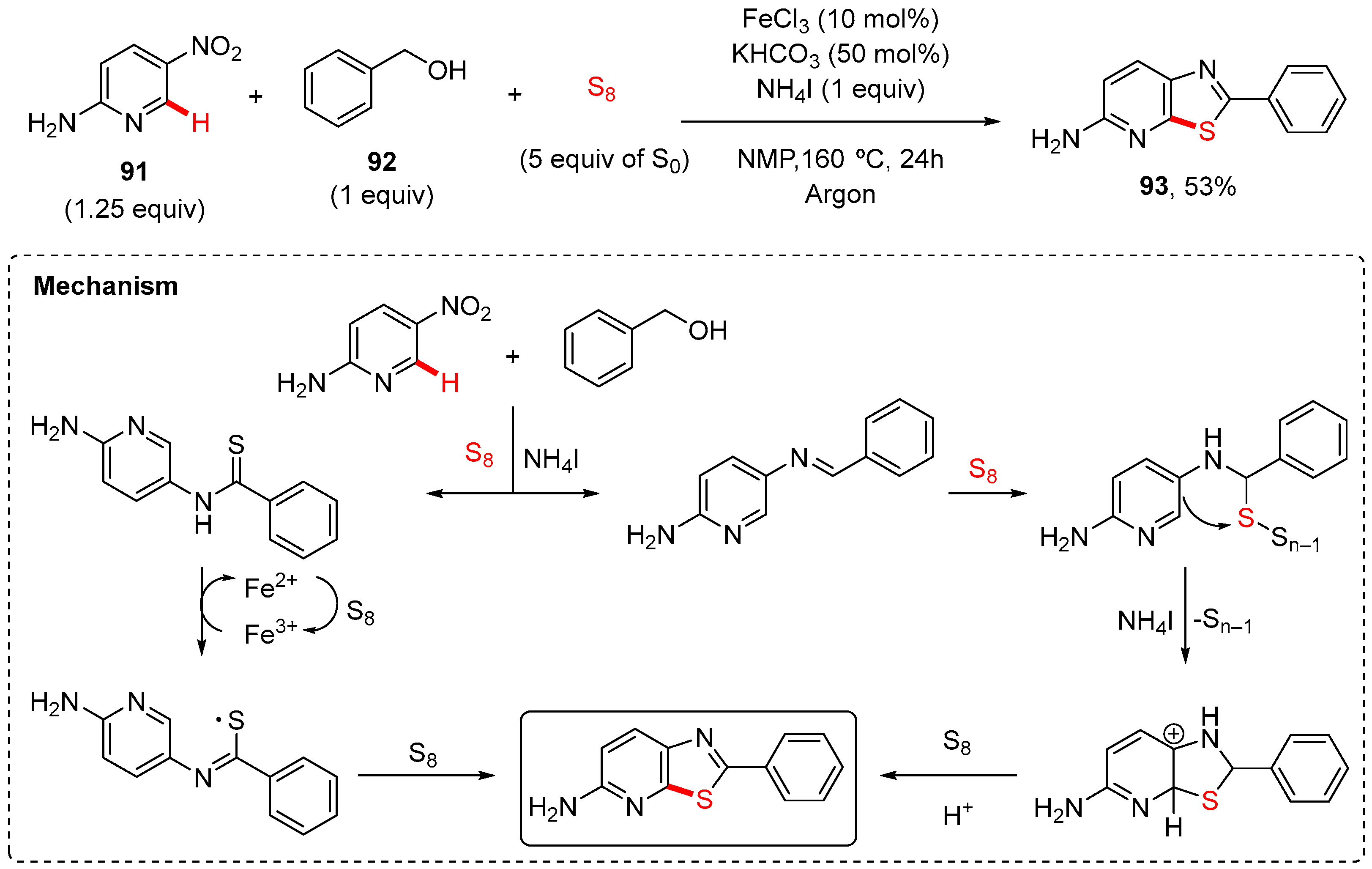

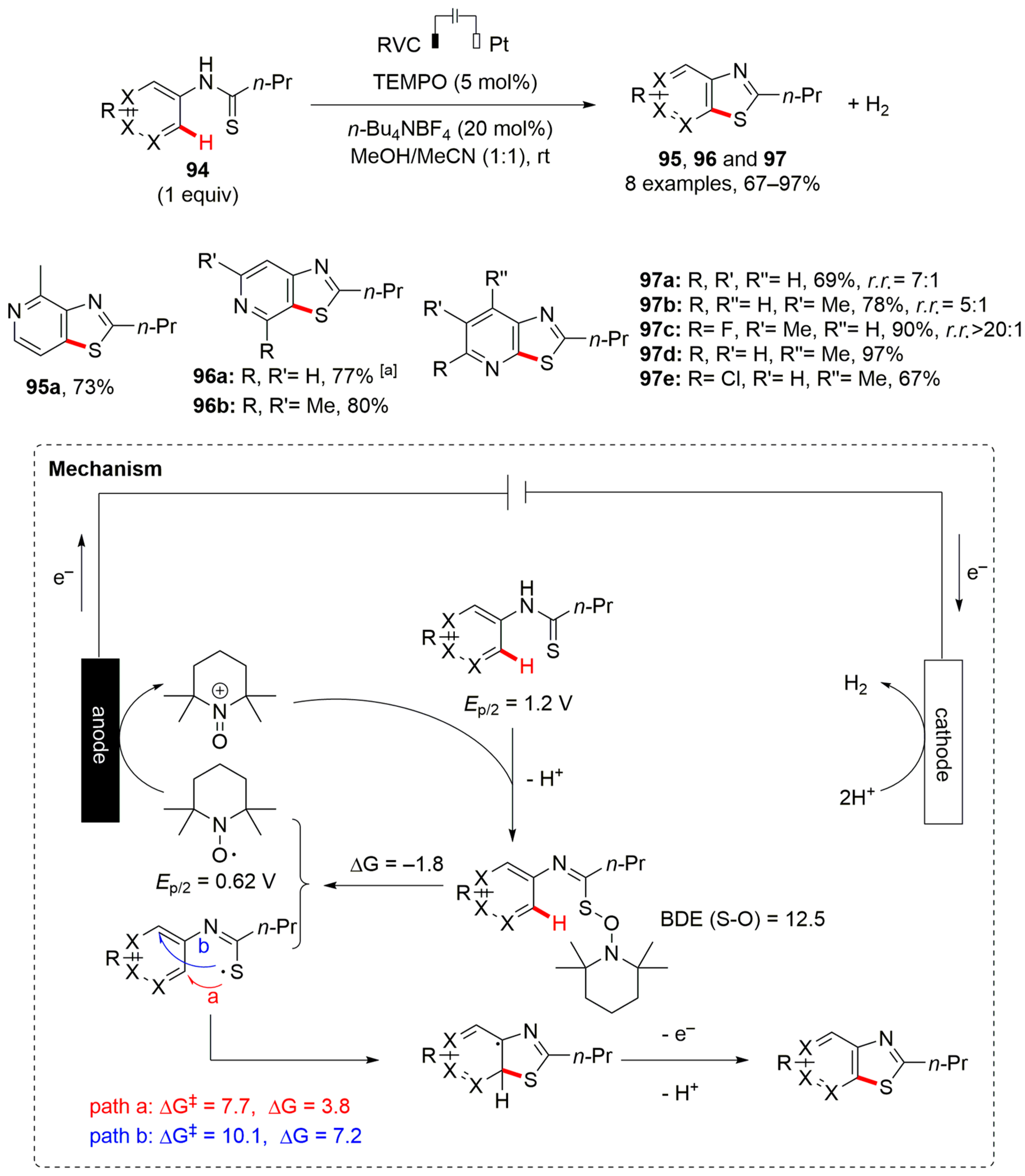

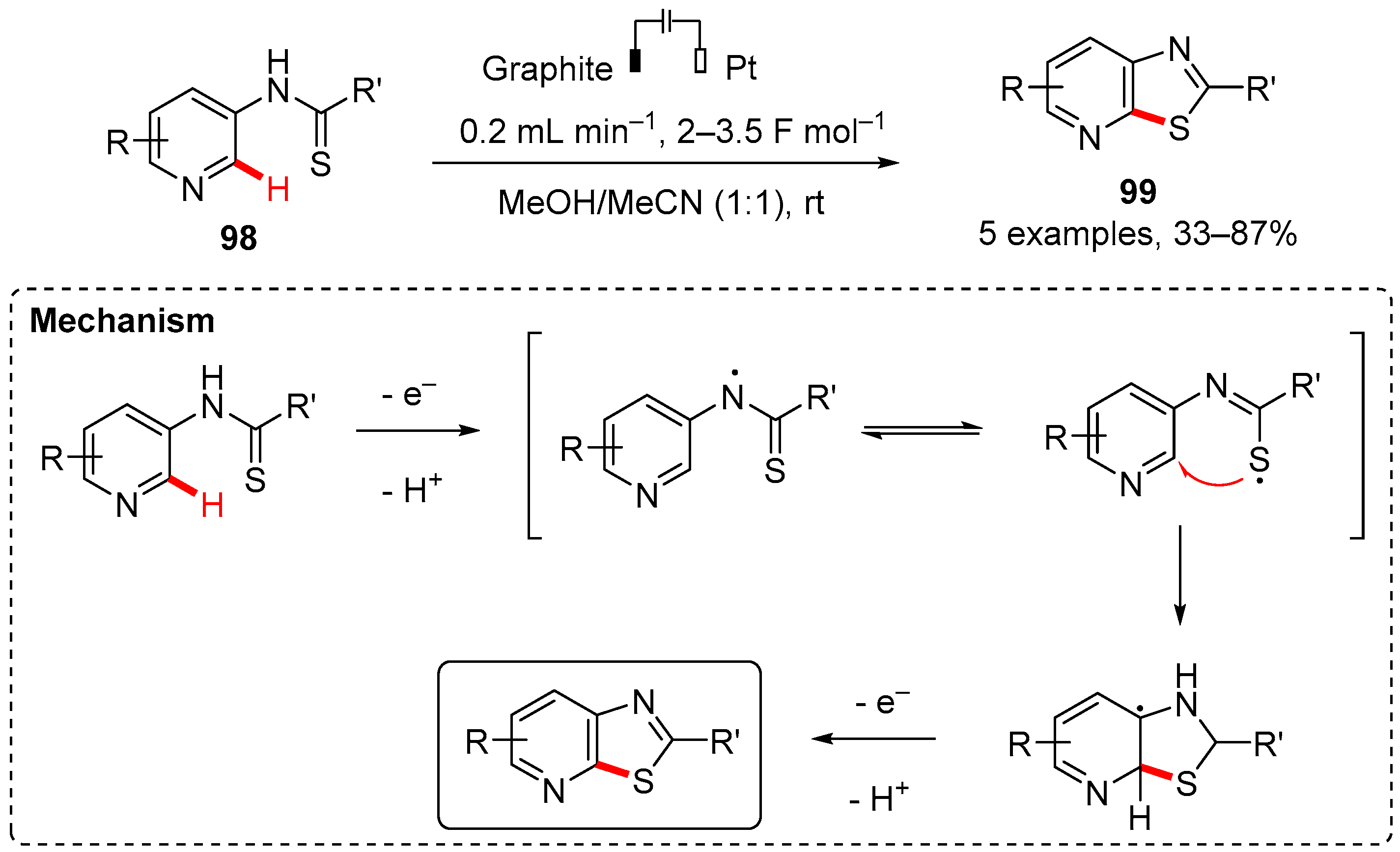

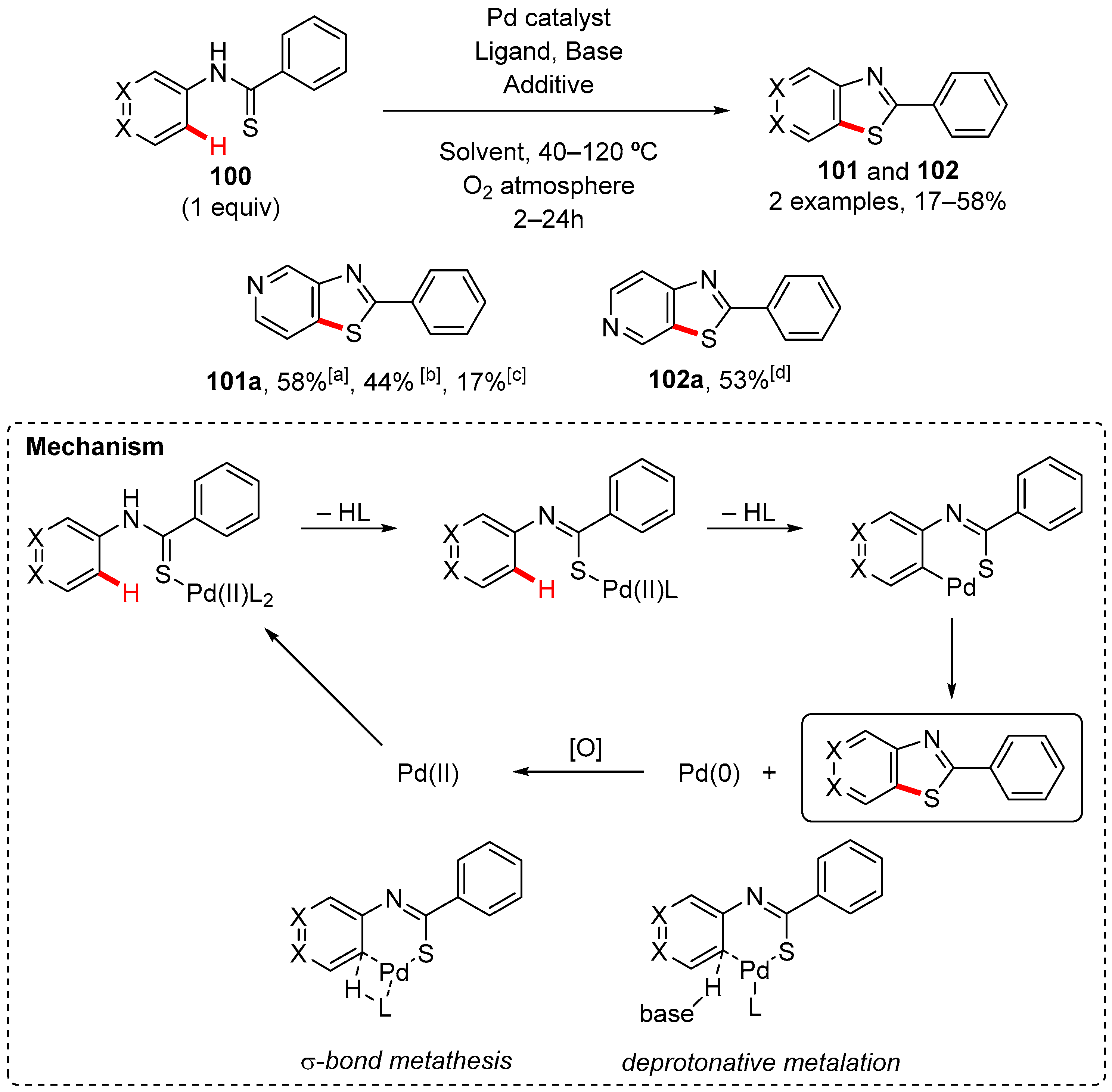

7. Thiazole-Fused to Azines

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,2-DCE | 1,2-dichloroethylene |

| BDE | Bond Dissociation Energy |

| Boc | tert-butoxycarbonyl |

| Bn | benzyl |

| CO | carbon monoxide |

| CYP2C9 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9 enzyme |

| DBU | 1,8-diazabicycloundec-7-ene |

| DCE | dichloroethane |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| DMAP | 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| equiv | equivalent |

| EWG | Electron-Withdrawing Group |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| LDA | lithium diisopropylamide |

| LiHMDS | lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide |

| MS | Molecular Sieve |

| MW | microwave |

| NAMPT | nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NMP | N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| PMB | p-methoxybenzyl |

| PPA | polyphosphoric acid |

| PTSA | p-toluenesulfonic acid |

| PyBrop | bromotripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate |

| r.r. | regioisomeric ratio |

| RVC | Reticulated Vitreous Carbon |

| TBHP | tert-butyl hydroperoxide |

| TEMPO | (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TMEDA | N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine |

References

- Ertl, P. Magic Rings: Navigation in the Ring Chemical Space Guided by the Bioactive Rings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2164–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Dadwal, A.; Kumar, B. Key Heterocyclic Moieties for the next Five Years of Drug Discovery and Development. Future Med. Chem. 2025, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampert, L.M.; Machado, B.R.; Joaquim, A.R.; Fumagalli, F. Rings in “Lead-like Drugs”. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 3851–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; O’Boyle, N.M. Analysis of the Structural Diversity of Heterocycles amongst European Medicines Agency Approved Pharmaceuticals (2014–2023). RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 4540–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.; Castro, J.L.; Lawson, A.D.G.; MacCoss, M.; Taylor, R.D. Rings in Clinical Trials and Drugs: Present and Future. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8699–8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauze, A.; Grinberga, S.; Krasnova, L.; Adlere, I.; Sokolova, E.; Domracheva, I.; Shestakova, I.; Andzans, Z.; Duburs, G. Thieno [2,3-b]Pyridines—A New Class of Multidrug Resistance (MDR) Modulators. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 5860–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojzych, M.; Šubertová, V.; Bielawska, A.; Bielawski, K.; Bazgier, V.; Berka, K.; Gucký, T.; Fornal, E.; Kryštof, V. Synthesis and Kinase Inhibitory Activity of New Sulfonamide Derivatives of Pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]Triazines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 78, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, F.; de Melo, S.M.G.; Ribeiro, C.M.; Solcia, M.C.; Pavan, F.R.; da Silva Emery, F. Exploiting the Furo[2,3-b]Pyridine Core against Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 974–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, A.; Gupta, S.; Ehlers, P.; Sekora, A.; Alammar, M.; Koczan, D.; Wolkenhauer, O.; Junghanss, C.; Langer, P.; Murua Escobar, H. Exploring Thiazolopyridine AV25R: Unraveling of Biological Activities, Selective Anti-Cancer Properties and In Silico Target and Binding Prediction in Hematological Neoplasms. Molecules 2023, 28, 8120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Duvelisib: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makker, V.; Recio, F.O.; Ma, L.; Matulonis, U.A.; Lauchle, J.O.; Parmar, H.; Gilbert, H.N.; Ware, J.A.; Zhu, R.; Lu, S.; et al. A Multicenter, Single-Arm, Open-Label, Phase 2 Study of Apitolisib (GDC-0980) for the Treatment of Recurrent or Persistent Endometrial Carcinoma (MAGGIE Study). Cancer 2016, 122, 3519–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markham, A. Fostemsavir: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conole, D.; Scott, L.J. Riociguat: First Global Approval. Drugs 2013, 73, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, K. FDA Approves Tofacitinib for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2012, 69, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Hong, S. Rh(III)-Catalyzed 7-Azaindole Synthesis via C–H Activation/Annulative Coupling of Aminopyridines with Alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11202–11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, L.; Vicente, R.; Kapdi, A.R. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Direct Arylation of (Hetero)Arenes by C-H Bond Cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009, 48, 9792–9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, C.M.; Federice, J.G.; Bell, C.N.; Cox, P.B.; Njardarson, J.T. An Update on the Nitrogen Heterocycle Compositions and Properties of U.S. FDA-Approved Pharmaceuticals (2013–2023). J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motati, D.R.; Amaradhi, R.; Ganesh, T. Azaindole Therapeutic Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.L.; Wakefield, B.J.; Wardell, J.A. Reactions of β-(Lithiomethyl)Azines with Nitriles as a Route to Pyrrolo-Pyridines, -Quinolines, -Pyrazines, -Quinoxalines and -Pyrimidines. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, G.; Palmieri, G.; Bosco, M.; Dalpozzo, R. The Reaction of Vinyl Grignard Reagents with 2-Substituted Nitroarenes: A New Approach to the Synthesis of 7-Substituted Indoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Meanwell, N.A.; Kadow, J.F.; Wang, T. A General Method for the Preparation of 4- and 6-Azaindoles. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 2345–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro-Ren, A.; Xue, Q.M.; Swidorski, J.J.; Gong, Y.-F.; Mathew, M.; Parker, D.D.; Yang, Z.; Eggers, B.; D’Arienzo, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Attachment. 12. Structure–Activity Relationships Associated with 4-Fluoro-6-Azaindole Derivatives Leading to the Identification of 1-(4-Benzoylpiperazin-1-Yl)-2-(4-Fluoro-7-[1,2,3]Triazol-1-Yl-1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-c]Pyridin-3-Yl)Ethane-1,2-Dione (BMS-585248). J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1656–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Pan, S.-L.; Su, M.-C.; Liu, Y.-M.; Kuo, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Wu, J.-S.; Nien, C.-Y.; Mehndiratta, S.; Chang, C.-Y.; et al. Furanylazaindoles: Potent Anticancer Agents in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8008–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Shin, K.; Chang, S. Iridium-Catalyzed C–H Amination with Anilines at Room Temperature: Compatibility of Iridacycles with External Oxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5904–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radix, S.; Hallé, F.; Mahiout, Z.; Teissonnière, A.; Bouchez, G.; Auberger, L.; Barret, R.; Lomberget, T. A Journey through Hemetsberger–Knittel, Leimgruber–Batcho and Bartoli Reactions: Access to Several Hydroxy 5- and 6-Azaindoles. Helv. Chim. Acta 2022, 105, e202100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.J.; Dufresne, C.; Lachance, N.; Leclerc, J.-P.; Boisvert, M.; Wang, Z.; Leblanc, Y. The Hemetsberger-Knittel Synthesis of Substituted 5-, 6-, and 7-Azaindoles. Synthesis 2005, 2005, 2751–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, M.; Yuen, P.; Liu, X.; Patel, S.; Sampath, D.; Oeh, J.; Liederer, B.M.; Wang, W.; O’Brien, T.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Minimizing CYP2C9 Inhibition of Exposed-Pyridine NAMPT (Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase) Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8345–8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnamour, J.; Bolm, C. Iron(II) Triflate as a Catalyst for the Synthesis of Indoles by Intramolecular C−H Amination. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2012–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugandar, S.; Konda, S.; Ila, H. Amine Directed Pd(II)-Catalyzed C–H Activation-Intramolecular Amination of N-Het(Aryl)/Acyl Enaminonitriles and Enaminones: An Approach towards Multisubstituted Indoles and Heterofused Pyrroles. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2035–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F.; EL-Atawy, M.A.; Muto, S.; Hagar, M.; Gallo, E.; Ragaini, F. Synthesis of Indoles by Palladium-Catalyzed Reductive Cyclization of β-Nitrostyrenes with Carbon Monoxide as the Reductant. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5712–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassman, P.G.; Van Bergen, T.J.; Gilbert, D.P.; Cue, B.W. General Method for the Synthesis of Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 5495–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, A.D.; Turner, C.I.; Deodhar, M.; Foot, J.S.; Jarolimek, W.; Zhou, W.; Robertson, A.D. Indole and Azaindole Haloallylamine Derivative Inhibitors of Lysyl Oxidases and Uses Thereof 2017. WO 2017/136871 A1, 10 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjadifar, S.; Vahedi, H.; Massoudi, A.; Louie, O. New 3H-Indole Synthesis by Fischer’s Method. Part I. Molecules 2010, 15, 2491–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanty, M.; Blu, J.; Suzenet, F.; Guillaumet, G. Synthesis of 4- and 6-Azaindoles via the Fischer Reaction. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5142–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomae, D.; Jeanty, M.; Coste, J.; Guillaumet, G.; Suzenet, F. Extending the Scope of the Aza-Fischer Synthesis of 4- and 6-Azaindoles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 3328–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseyev, R.S.; Amirova, S.R.; Kabanova, E.V.; Terenin, V.I. The Fischer Reaction in the Synthesis of 2,3-Disubstituted 7-Azaindoles*. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2014, 50, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseyev, R.S.; Amirova, S.R.; Terenin, V.I. Synthesis of 5-Chloro-7-Azaindoles by Fischer Reaction. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2017, 53, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, M.; Carbone, A.; Moody, C.J. Two-Step Route to Indoles and Analogues from Haloarenes: A Variation on the Fischer Indole Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, R.E.; Gerstenberger, B.S. A Direct Copper-Catalyzed Route to Pyrrolo-Fused Heterocycles from Boronic Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.; Martins, M.M.; Mortinho, A.C.; Silva, A.M.S.; Marques, M.M.B. Exploring the Reactivity of Halogen-Free Aminopyridines in One-Pot Palladium-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling/C–H Functionalization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 152303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhao, J.; Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, P. Transition-Metal-Free Access to 7-Azaindoles. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 4100–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, Z.; Randolph, C.; Buravov, O.; Mykhailiuk, P.; Kürti, L. Harnessing O-Vinylhydroxylamines for Ring-Annulation: A Scalable Approach to Azaindolines and Azaindoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 27148–27154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-M.; Huang, H.; Pu, Y.; Tian, W.; Deng, Y.; Lu, J. A Close Look into the Biological and Synthetic Aspects of Fused Pyrazole Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, 114739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, H.-A.; Galiè, N.; Grimminger, F.; Grünig, E.; Humbert, M.; Jing, Z.-C.; Keogh, A.M.; Langleben, D.; Kilama, M.O.; Fritsch, A.; et al. Riociguat for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmann, M.; Ackerstaff, J.; Redlich, G.; Wunder, F.; Lang, D.; Kern, A.; Fey, P.; Griebenow, N.; Kroh, W.; Becker-Pelster, E.-M.; et al. Discovery of the Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulator Vericiguat (BAY 1021189) for the Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5146–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Xu, H.; Nie, P.; Xie, X.; Nie, Z.; Rao, Y. Synthesis of Indazoles and Azaindazoles by Intramolecular Aerobic Oxidative C–N Coupling under Transition-Metal-Free Conditions. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 3932–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojzych, M.; Kubacka, M.; Mogilski, S.; Filipek, B.; Fornal, E. Relaxant Effects of Selected Sildenafil Analogues in the Rat Aorta. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojzych, M. Synthesis of Phenylhydrazone of 5-Acetyl-3-(Methylsulfanyl)-1,2,4-Triazine and 3-Methyl-5-(Methylsulfanyl)-1-Phenyl-1H-Pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]Triazine from Pivotal Intermediate. Molbank 2005, 2005, M404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojzych, M.; Rykowski, A. Transformations of Phenylhydrazones of 5-Acyl-1,2,4-Triazines to Pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]Triazines or 4-Cyanopyrazole. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 44, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojzych, M.; Tarasiuk, P.; Kotwica-Mojzych, K.; Rafiq, M.; Seo, S.-Y.; Nicewicz, M.; Fornal, E. Synthesis of Chiral Pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]Triazine Sulfonamides with Tyrosinase and Urease Inhibitory Activity. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filák, L.; Rokob, T.A.; Vaskó, G.Á.; Egyed, O.; Gömöry, Á.; Riedl, Z.; Hajós, G. A New Cyclization to Fused Pyrazoles Tunable for Pericyclic or Pseudopericyclic Route: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 3900–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Block, M.A.; Cowen, S.; Davies, A.M.; Devereaux, E.; Gingipalli, L.; Johannes, J.; Larsen, N.A.; Su, Q.; Tucker, J.A.; et al. Discovery of Azabenzimidazole Derivatives as Potent, Selective Inhibitors of TBK1/IKKε Kinases. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambwe, D.; Coertzen, D.; Leshabane, M.; Mulubwa, M.; Njoroge, M.; Gibhard, L.; Girling, G.; Wicht, K.J.; Lee, M.C.S.; Wittlin, S.; et al. hERG, Plasmodium Life Cycle, and Cross Resistance Profiling of New Azabenzimidazole Analogues of Astemizole. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

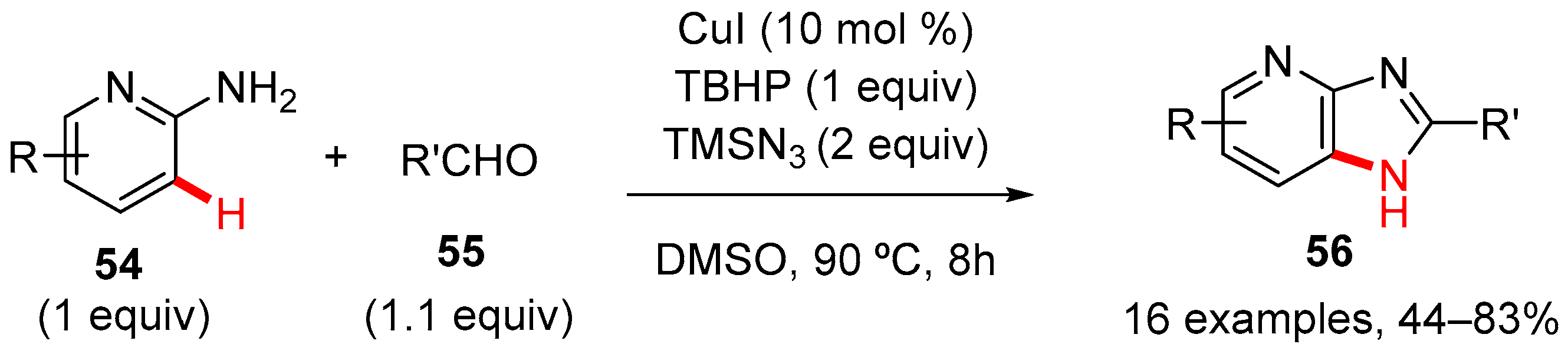

- Nisha; Bhargava, G.; Kumar, Y. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective C-H Amination of N-Pyridyl Imines Using Azidotrimethylsilane and TBHP: A One-Pot, Domino Approach to Substituted Imidazo[4, 5-b]Pyridines. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 7827–7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

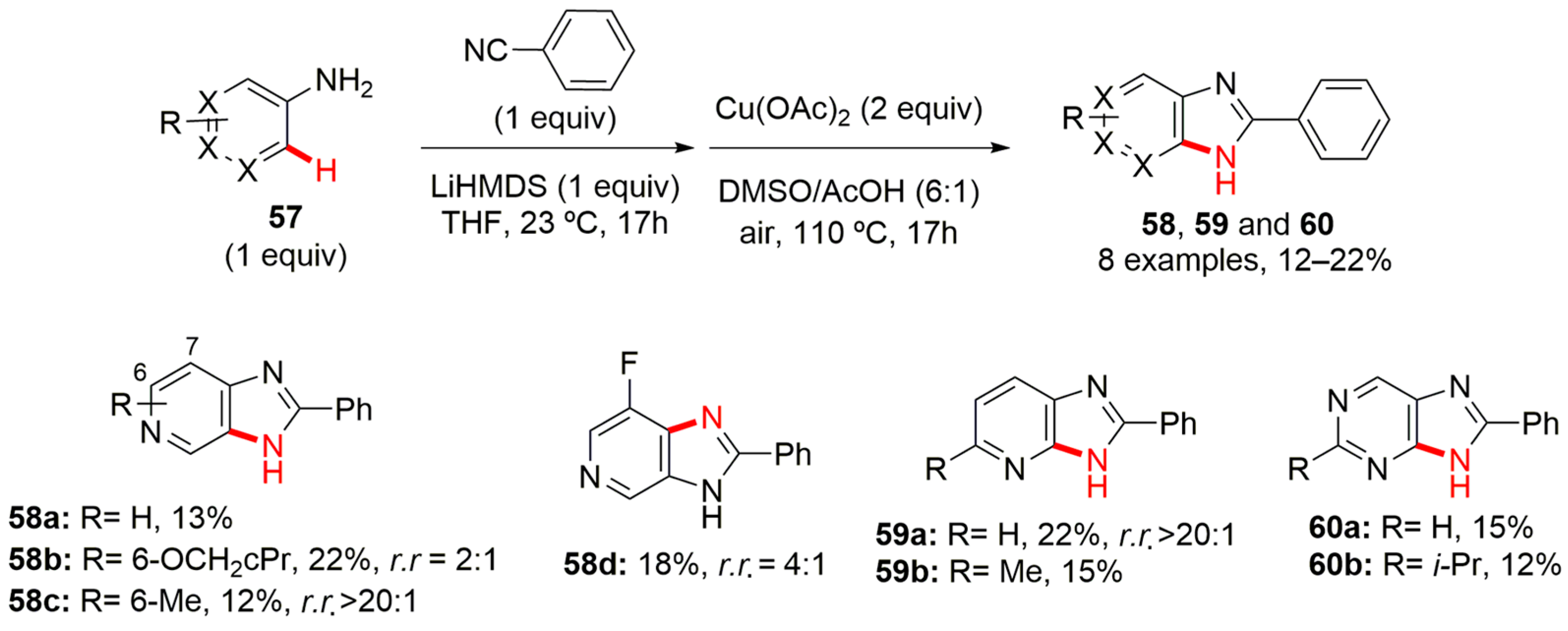

- Arnold, E.P.; Mondal, P.K.; Schmitt, D.C. Oxidative Cyclization Approach to Benzimidazole Libraries. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

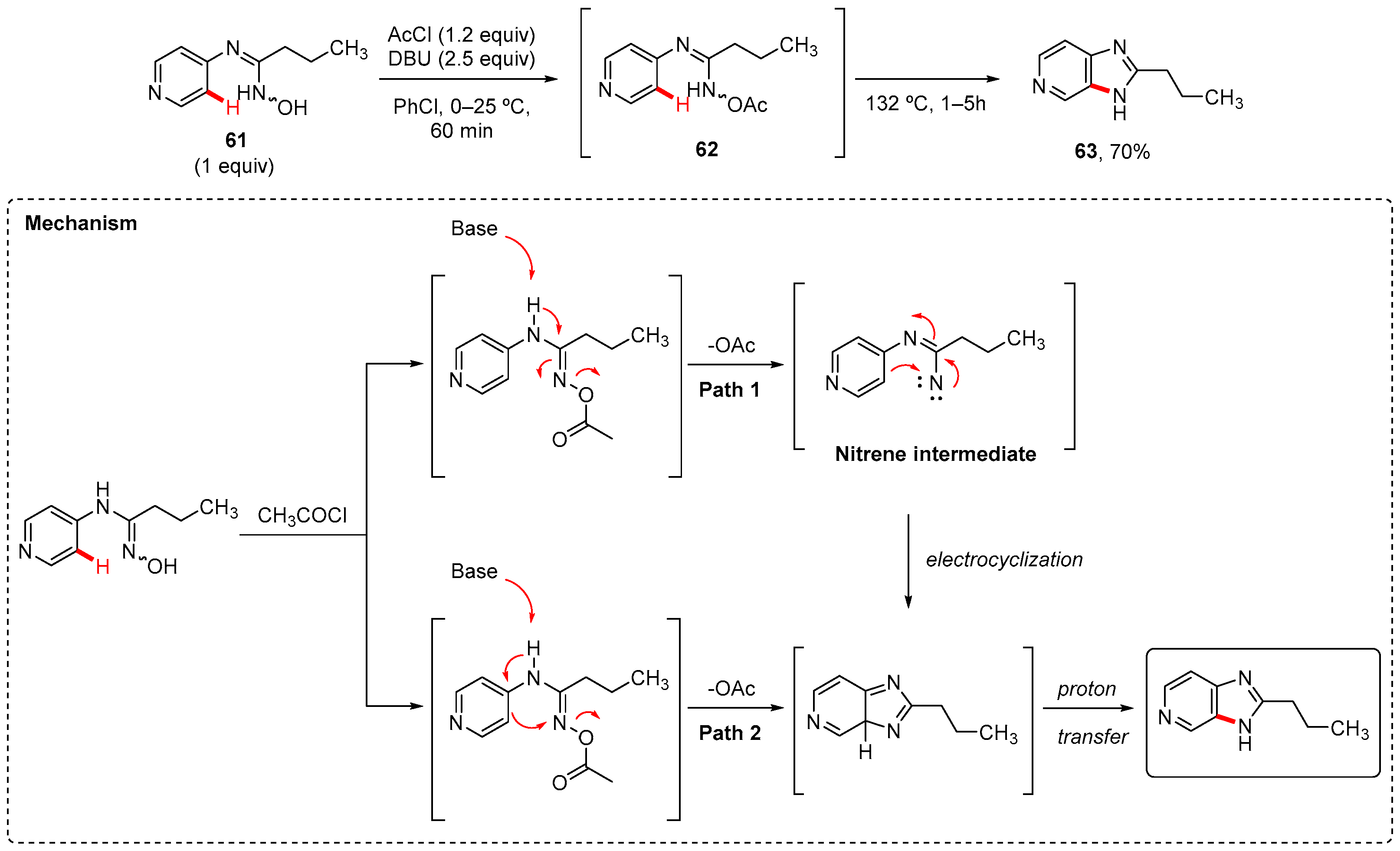

- Qin, H.; Odilov, A.; Bonku, E.M.; Zhu, F.; Hu, T.; Liu, H.; Aisa, H.A.; Shen, J. Facile Synthesis of Benzimidazoles via N-Arylamidoxime Cyclization. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45678–45687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirakanyan, S.N.; Hovakimyan, A.A.; Noravyan, A.S. Synthesis, Transformations and Biological Properties of Furo[2,3-b]Pyridines. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2015, 84, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Robinson, R.G.; Fu, S.; Barnett, S.F.; Defeo-Jones, D.; Jones, R.E.; Kral, A.M.; Huber, H.E.; Kohl, N.E.; Hartman, G.D.; et al. Rapid Assembly of Diverse and Potent Allosteric Akt Inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2211–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huang, M.; Li, G.; Zheng, S.; Yu, P. Scalable Synthesis of a Tetrasubstituted 7-Azabenzofuran as a Key Intermediate for a Class of Potent HCV NS5B Inhibitors. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

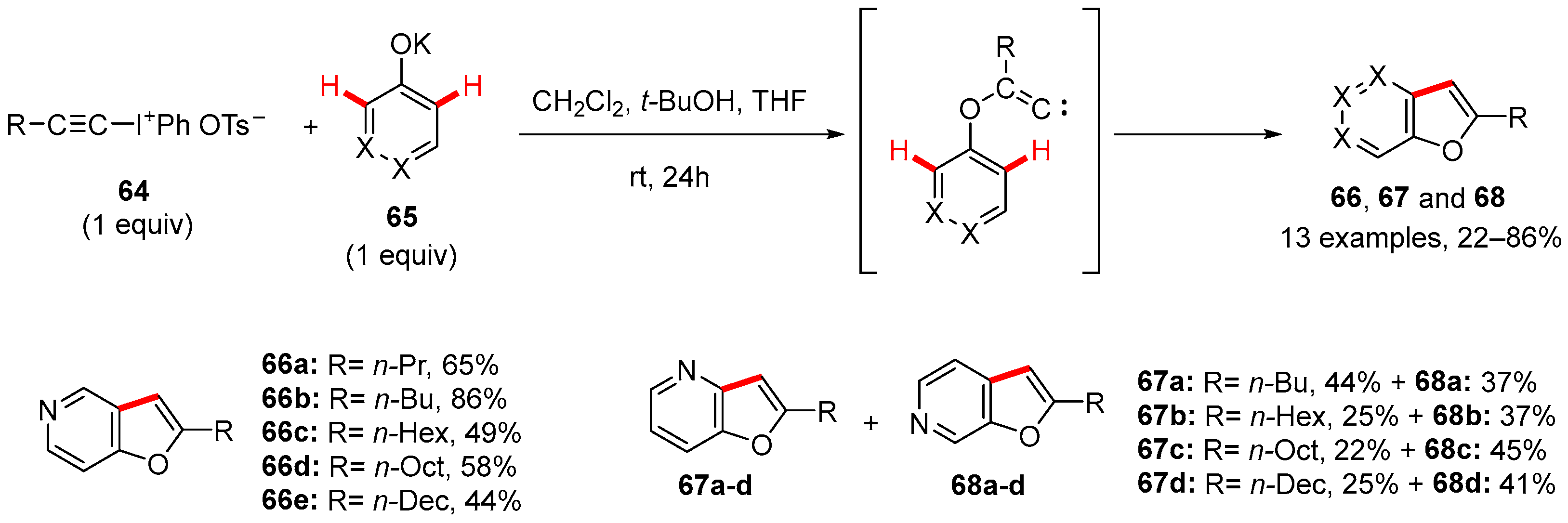

- Kitamura, T.; Tsuda, K.; Fujiwara, Y. Novel Heteroaromatic C–H Insertion of Alkylidenecarbenes. A New Entry to Furopyridine Synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5375–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, F.; da Silva Emery, F. Charting the Chemical Reactivity Space of 2,3-Substituted Furo[2,3-b]Pyridines Synthesized via the Heterocyclization of Pyridine-N-Oxide Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 10339–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhao, J.; Yu, P. Access to Furo[2,3-b]Pyridines by Transition-Metal-Free Intramolecular Cyclization of C3-Substituted Pyridine N-Oxides. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rateb, N.M.; Abdelaziz, S.H.; Zohdi, H.F. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Some New Thienopyridine, Pyrazolopyridine and Pyridothienopyrimidine Derivatives. J. Sulfur Chem. 2011, 32, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi El-Deen, E.M.; Abd El-Meguid, E.A.; Hasabelnaby, S.; Karam, E.A.; Nossier, E.S. Synthesis, Docking Studies, and In Vitro Evaluation of Some Novel Thienopyridines and Fused Thienopyridine–Quinolines as Antibacterial Agents and DNA Gyrase Inhibitors. Molecules 2019, 24, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, E.M.H.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.S.; Oh, C.-H. Thieno[2,3-d]Pyrimidine as a Promising Scaffold in Medicinal Chemistry: Recent Advances. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 1159–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagardère, P.; Fersing, C.; Masurier, N.; Lisowski, V. Thienopyrimidine: A Promising Scaffold to Access Anti-Infective Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, A.; Kumar, S.V.; Ila, H. Diversity-Oriented Synthesis of Substituted Benzo[b]Thiophenes and Their Hetero-Fused Analogues through Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative C–H Functionalization/Intramolecular Arylthiolation. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 21, 17116–17125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiah, B.; Gautam, V.; Acharya, A.; Pasha, M.A.; Hiriyakkanavar, I. One-Pot Synthesis of 2-(Aryl/Alkyl)Amino-3-Cyanobenzo[b]Thiophenes and Their Hetero-Fused Analogues by Pd-Catalyzed Intramolecular Oxidative C–H Functionalization/Arylthiolation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 5679–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, Y. Access to Thienopyridine and Thienoquinoline Derivatives via Site-Selective C–H Bond Functionalization and Annulation. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 3167–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.F.; Alam, A.; Alshammari, A.A.; Alhazza, M.B.; Alzimam, I.M.; Alam, M.A.; Mustafa, G.; Ansari, M.S.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Alotaibi, A.A.; et al. Thiazole: A Versatile Standalone Moiety Contributing to the Development of Various Drugs and Biologically Active Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamshany, Z.M. Design, Synthesis, and Antimicrobial Evaluation of New Antipyrine Derivatives Bearing Thiazolopyridazine and Pyrazolothiazole Scaffolds. Synth. Commun. 2024, 54, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; Behbehani, H. The First Q-Tube Based High-Pressure Synthesis of Anti-Cancer Active Thiazolo[4,5-c]Pyridazines via the [4 + 2] Cyclocondensation of 3-Oxo-2-Arylhydrazonopropanals with 4-Thiazolidinones. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.S.; Nawaz, A.; Aslam, S.; Ahmad, M.; Zahoor, A.F.; Mohsin, N.U.A. Synthetic Strategies for Thiazolopyridine Derivatives. Synth. Commun. 2023, 53, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruit, C.; Turck, A.; Plé, N.; Quéguiner, G. Syntheses of N-Diazinyl Thiocarboxamides and of Thiazolodiazines. Metalation Studies. Diazines XXXIII. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2002, 39, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Yamaji, M.; Maki, S.; Niwa, H.; Hirano, T. Substituent Effects on Fluorescence Properties of Thiazolo[4,5-b]Pyrazine Derivatives. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzin, I.V.; Smirnova, N.G.; Yarovenko, V.N.; Krayushkin, M.M. Synthesis of 5-Aminothiazolo[4,5-b]Pyridine-2-Carboxamides. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2004, 53, 1353–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-Z.; Zhi, Y.-G. An Efficient Method for the Construction of 2-Aminothiazolo[5,4-c]Pyridines via K3[Fe(CN)6] Oxidized SP2 CH Functionalization. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 8610–8616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Singh, A.; Sonar, P.; Mishra, M.; Saraf, S. Schiff Bases of Benzothiazol-2-Ylamine and Thiazolo[5,4-b] Pyridin-2-Ylamine as Anticonvulsants: Synthesis, Characterization and Toxicity Profiling. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kim, J. Copper-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidation of Amines to Benzothiazoles via Cross Coupling of Amines and Arene Thiolation Sequence. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 3576–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Ma, Y.; Xie, H.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, F.; Deng, G.-J. Iron-Promoted Three-Component 2-Substituted Benzothiazole Formation via Nitroarene Ortho-C–H Sulfuration with Elemental Sulfur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.-Y.; Li, S.-Q.; Song, J.; Xu, H.-C. TEMPO-Catalyzed Electrochemical C–H Thiolation: Synthesis of Benzothiazoles and Thiazolopyridines from Thioamides. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2730–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueiras-Amador, A.A.; Qian, X.-Y.; Xu, H.-C.; Wirth, T. Catalyst- and Supporting-Electrolyte-Free Electrosynthesis of Benzothiazoles and Thiazolopyridines in Continuous Flow. Chemistry 2018, 24, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamoto, K.; Hasegawa, C.; Kawasaki, J.; Hiroya, K.; Doi, T. Use of Molecular Oxygen as a Reoxidant in the Synthesis of 2-Substituted Benzothiazoles via Palladium-Catalyzed C-H Functionalization/Intramolecular C-S Bond Formation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2643–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamoto, K.; Nozawa, K.; Kondo, Y. Palladium-Catalyzed C-H Cyclization in Water: A Milder Route to 2-Arylbenzothiazoles. Synlett 2012, 23, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Theisen, M.C.; de Borba, I.A.S.; Joaquim, A.R.; Fumagalli, F. C–H Annulation in Azines to Obtain 6,5-Fused-Bicyclic Heteroaromatic Cores for Drug Discovery. Reactions 2025, 6, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040072

Theisen MC, de Borba IAS, Joaquim AR, Fumagalli F. C–H Annulation in Azines to Obtain 6,5-Fused-Bicyclic Heteroaromatic Cores for Drug Discovery. Reactions. 2025; 6(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheisen, Maria Carolina, Isis Apolo Silveira de Borba, Angélica Rocha Joaquim, and Fernando Fumagalli. 2025. "C–H Annulation in Azines to Obtain 6,5-Fused-Bicyclic Heteroaromatic Cores for Drug Discovery" Reactions 6, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040072

APA StyleTheisen, M. C., de Borba, I. A. S., Joaquim, A. R., & Fumagalli, F. (2025). C–H Annulation in Azines to Obtain 6,5-Fused-Bicyclic Heteroaromatic Cores for Drug Discovery. Reactions, 6(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040072