1. Introduction

Hexavalent chromium coatings are being systematically substituted with less toxic trivalent chromium-based alternatives [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Protsenko [

2] reviewed approximately 140 studies of the mechanism of the electrochemical reactions of electrodeposition from

baths. The electroreduction in

ions proceeds through the following reactions:

Reactions with 3 electrons of one stage are unlikely, and the formation of as an intermediate oxidation state is questionable.

Notably, in 1933, Kasper [

9] identified the structure

as the predominant species of the trivalent chromium ion in an acidic medium, and in 1976, the hexa-aquo ion was identified via X-ray diffraction as the stable species of trivalent chromium [

10]. Mandich [

6] noted the following reactions of this hexa-aquo complex of chromium:

Oxalation

where in Equations (3)–(9), the chrome atoms have a 3+ oxidation state.

The mechanisms of coating formation in these studies consider the

ion as a source of chromium in the coating. The mechanics proposed in several studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] proceed through reactions (10)–(13) as follows:

where

,

, and

are integer numbers.

We call the scheme of reactions (10)–(13) the inner-sphere complex hypothesis. Reactions (10)–(13) have been proposed on the basis of the results of electrochemical methods [

2,

3], quartz crystal microbalance [

2], and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry [

7]. These techniques do not provide direct information about the formation of

. Moreover, via density functional theory (DFT), Zeng et al. [

8] calculated the equilibrium structures of the inner complex formed in reaction (10). However, in our experience, DFT analysis has not captured the oxyphilic character of some metallic atoms. To support this opinion, the following example is provided. A DFT study proposed that electro-oxidation of methanol occurs in consecutive dehydrogenation steps [

11] and predicted that the final product was

[

11]. However, the cyclic voltammetry and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results [

12] are not in line with the predictions of DFT [

11], and this is explained by the high adsorption energy of oxygen on rhenium, which blocks the adsorption of methanol species on the surface. Consequently, the oxyphilic character of rhenium is overlooked in DFT studies, and similar problems should occur in the DFT calculations of

reactivity. We are interested in contributing to evaluating the inner-sphere complex forms as predicted by the DFT study.

The monomers

are kinetically inert; therefore, the overvoltage for reduction is very high. In the literature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], the central idea is to replace water molecules in the hexa-aquo complex of

with

, and then, it is presumably easier to reduce this new compound than the aquo complex. This is the inner-sphere complex hypothesis, which is based on a set of chemical reactions (10)–(13). It is subsequently necessary to input high energy into the system to replace a water molecule in the complex. Thus, the baths were prepared with a temperature near the boiling point of water and a long reaction time. However, the lack of characterization of species in solution does not support the formation of an inner complex (

) in the electroplating bath, or at least, there is no clear indication that these compounds are the key factor in the formation of high-quality deposits. This approach is based only on UV–Vis (Ultraviolet–visible) spectroscopy, which has the following disadvantages:

UV–Vis spectroscopy does not provide direct information on the existence of or bonds;

A high concentration of ions produces a saturated signal, and consequently, the bath is diluted several times. Thus, the measurement corresponds to another bath condition;

The UV–Vis absorption spectra of

oligomers (monomers, dimers and trimers) have been well characterized [

13], and the experimental spectra in the studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] can be related to the effect of

on the relative concentrations of these oligomers in a diluted bath; that is,

inhibits reactions (6)–(9) or

can retard the formation of dimers and trimers in a diluted solution;

The ionic strength of the bath influences the wavelength of maximum absorption; these shifts are usually due to differences in the solvation energies of the molecules, and there are a few cases related to the existence of the chlore complexes [

14].

The slow formation of metal complexes is recognized in the majority of studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]; however, the data are not considered in real dimensions. First,

bonds are more than 40 kJ/mole stronger than other

bond metals [

15], and consequently, this implies that the bonds of

ions are covalent [

10]. Second, the residence time of the oxygen atoms of water molecules in the first hydration shell is on the order of 36–56 h, depending on the ionic strength [

16]. In addition, Bokare and Choi [

17] noted that the

compound is unreactive toward the

species. Finally, the NMR isotope dilution method revealed that

does not react with anions to form complexation products [

16]. These data are not addressed in the studies in

Figure 1; accordingly, they do not describe the actual process. Therefore, the formation of

in bath solutions is rather improbable.

At neutral or basic pH values, it is practically impossible to prepare only hexa-aquo monomers because of the tendency of

to form oligomers (reactions (6)–(9)) [

18]. In this regard, Bobrowski [

19] reviewed 173 articles and noted that complex

ions are unreactive; however,

ions formed instantaneously from the electrochemical reduction of

ions to

somewhat reactively. One possible explanation should be considered: the concentrations of oligomers are very low in the solution where

has just formed, and reactions (6)–(13) have not yet occurred. The

inner complexes are usually formed by vigorous reactions between

and organic substances. Moreover, the complexation products of the

cation with anions (

,

, etc.) can be synthesized only by the reduction of chromic acid with hydrogen peroxide [

18]. The synthesis of these complexes is quite different from the preparation of electroplating baths. In this context, the inner-sphere chromochloro aquo complexes formed from

are stable at high concentrations of

(12 M) or in solutions with a pH < 1 containing 1 mol of chloride ions [

20], which is not usually the condition of an electroplating bath. In addition, in bath solutions, the inner-sphere complexes have slow kinetics (on the order of days) [

21]), and these compounds are stable at pH values greater than 4, which is not the pH of trivalent baths.

Only three studies have used vibrational spectroscopy to determine the species in solutions [

22,

23,

24]. However, the infrared spectra reported in these studies do not include the region between 500 and 1000 cm

−1, which is in the zone where bands of

bonds appear. The formation of

bonds is the core concept underlying the inner-sphere complex hypothesis. Consequently, there is no evidence for this hypothesis. In our study, we synthesized a complex containing

bonds and compared this compound with species in

baths. If

are detected at significant concentrations, then the inner-sphere complex hypothesis can explain the role of additives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Accessory Equipment

The compounds used in the laboratory experiments were chromium (III) sulfate (>99% purity), potassium dichromate (99% purity), ammonium oxalate (99.99% purity), oxalic acid (99% purity), sodium acetate (99.3% purity), boric acid (99.9% purity), potassium sulfate (99% purity), sodium sulfate (99.4% purity), ethanol (99% purity), and sulfuric acid (99% purity). The supplier companies were J.T. Baker Chemical Co. (Avantor, Inc., Radnor, PA, USA), Fermont (Productos Químicos Monterrey, S.A. de C.V.) Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico, and Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Deionized water (1 µS cm−2) was obtained via MilliporeSigma equipment (Merck KGaA, Burlington, MA, USA). A Thermo Scientific Eutech Elite (Thermo Scientific™ Waltham, MA, USA) pH meter was used to measure the pH.

2.2. Synthesis of the Bis(Oxalato) Diaqua Chromate (III) Dihydrate Cis Isomer

Potassium bis(oxalato) diaqua chromate (III) dihydrate was synthesized in our laboratories and is abbreviated as the cis isomer. The synthesis was reported by Kauffman [

25], and the process is described in general terms: potassium dichromate is mixed with oxalic acid, and the reaction occurs when a very small amount of water is added to the mixture. The reaction is exothermic and produces CO

2 gas and violet crystals, which are subsequently washed with ethanol and dried. For synthesis, standard laboratory glassware (borosilicate glass) and a mercury thermometer (Kessler Thermometer Corp., West Babylon, NY, USA) were used.

2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy in Attenuated Total Reflectance Mode

Two solutions were studied: (1) a solution similar to a bath prepared by adding salts of several compounds at the concentrations used in the electrodeposition process and (2) a violet crystal salt cis isomer dissolved in aqueous media. In this solution, other components were added to resemble bath plating. This solution was compared with a solution of chromium (III) sulfate. In all the solutions, the concentration of was equal (0.6 M) and contained equivalent concentrations of additive, buffer and conductive compounds. For all the solutions, aliquots of sulfuric acid (1 M) were used to adjust the pH to 3.1.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode to analyze the solids and aqueous bath solutions. The equipment used was a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two model (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT, USA). The measurements were carried out at room temperature (20–25 °C). The sample base plate was a diamond coating. The signal-to-noise ratio was 15,000:1. The resolution of the measurement was 4 cm−1, with 1000 scans per sample. The measurement window was 400–4000 cm−1, and the equipment had a high-resolution lithium tantalate ()) detector (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT, USA) with an Opt KBr beam splitter (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT, USA). Before the measurements, the background was recorded in the atmosphere. The liquid samples of the solutions were subsequently placed with a previous preparation time of less than 12 h and were placed in the detector, and tightening was performed where the torque of 80% of the force was adjusted according to the sensitivity of the equipment. All the solid samples were pressed into contact with the ATR crystal.

The reference spectrum (

) recorded in deionized water was subtracted from the spectrum of a solution (

), and the difference between the spectrum of pure water and the spectrum with the IR active species was normalized (

) to the reference spectrum. Then,

was calculated as follows

3. Results

The synthesis of trivalent chromium compounds with oxalates has been widely reported [

25]. The violet crystal product of the synthesis reaction (15) corresponds to the compound to cis isomer.

The cis isomer contains bonds and terminal bonds (); that is, this compound possesses the same two oxalic groups occupying adjacent positions, and these groups share a common chromium atom (vertex) and form an angle between them. The cis isomer is the compound according to the inner-sphere complex hypothesis. On the other hand, the monomer has bonds, and consequently, the crystal structures of the majority of compounds have octahedral symmetry with six water molecules at their six apices. Therefore, differences in the spectra can be expected between the inner-sphere complex and the monomer.

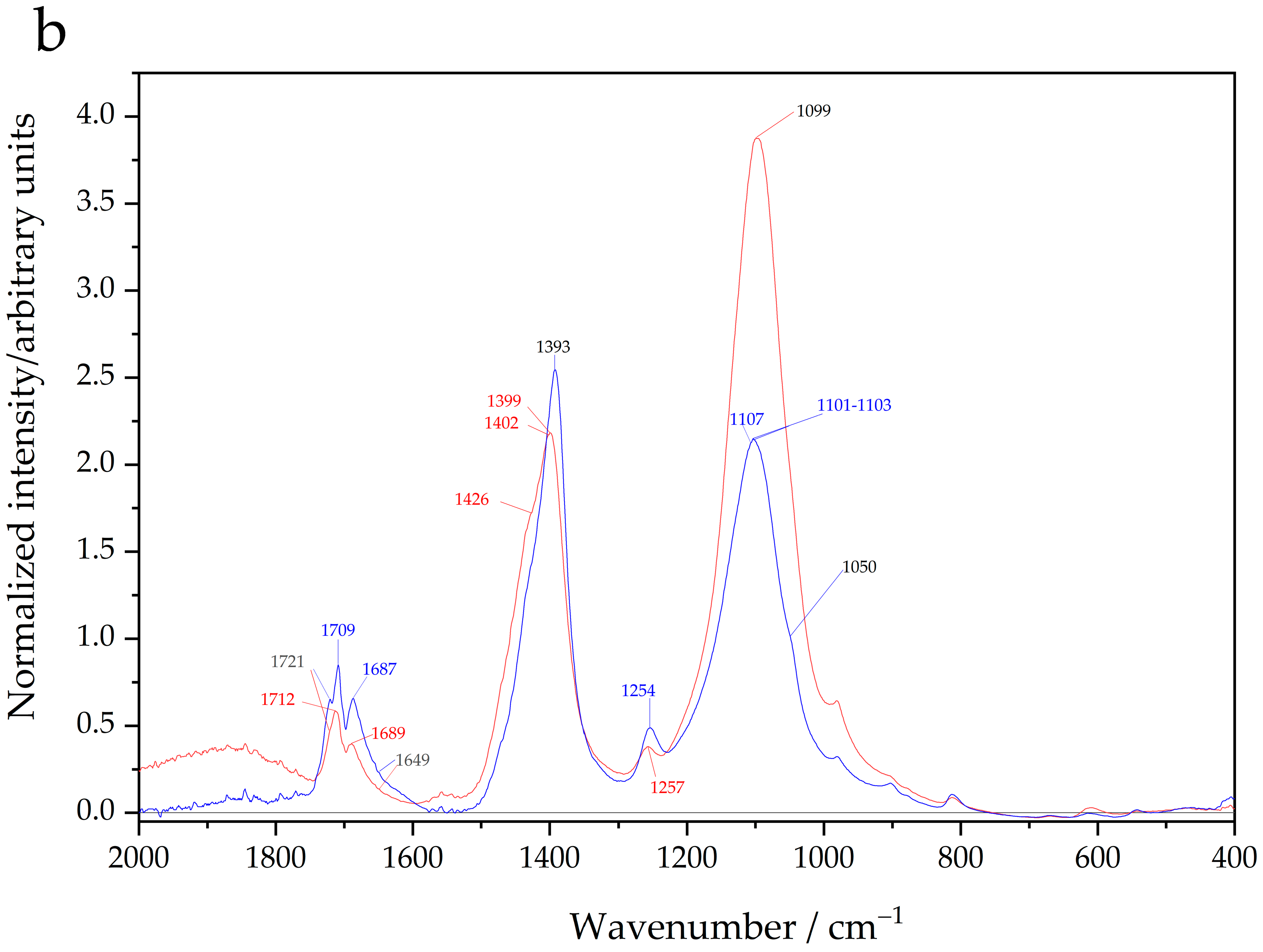

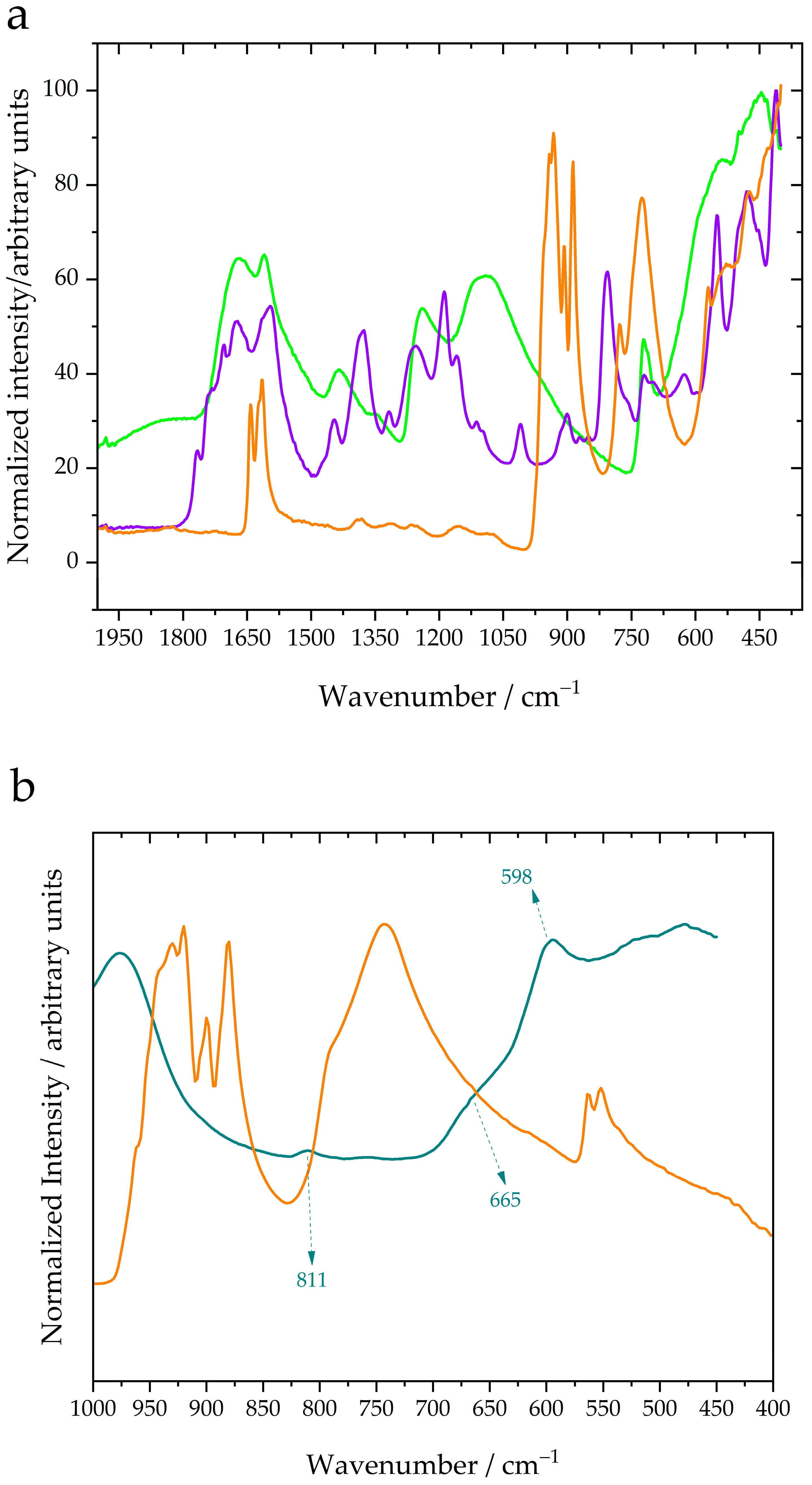

The spectra of oxalic acid and dichromate potassium hydrated in

Figure 1a were used to facilitate the tentative assignment of vibrational modes of the bonds of the cis isomer, and

Figure 1b shows the spectra of dichromate potassium anhydrous and chromium (III) sulfate to assist in the identification of the bands of the

dissolved compounds.

The majority of salts are hydrated; consequently, the features in the spectra observed at wavenumbers less than 600 cm

−1 are related to the water in the crystal structure. This is clearly observed in the difference between the dichromate spectra in

Figure 1a (hydrated crystals) and

Figure 1b (anhydrous crystals). Additionally, features in the spectra centered at approximately 1600–1650 cm

−1 are assigned to the

vibrational modes of interstitial water. Jacewicz et al. [

26] reported the IR transmission spectra of the cis isomer, and there are some differences in the intensities of the bands between the transmission spectra and the FTIR-ATR spectra in

Figure 1a; however, the spectra are similar in general terms. Note that transmission infrared mode light passes directly through the sample, and in FTIR-ATR mode, spectra are obtained from the absorption of the infrared wave, which penetrates a few micrometers of the sample. Consequently, there are differences in spectral sensitivity between techniques.

In a review of the spectra of the

and

of coatings, Avalos et al. [

27] reported an inequality in the stretching vibrational modes:

where

symbolizes the wavenumbers of the positions of the bands related to the bonds indicated in parenthesis. In

Figure 1b, inequality also applies to the

bonds of chromium (III) sulfate compared with the

bonds in dichromate oxide. Note that in

Figure 1b, the band at 980 cm

−1 is related to the sulfate group of chromium (III) sulfate. The vibrational modes of terminal bonds (

) in dichromate oxide between 746 and 968 cm

−1 were reported by Bates et al. [

28], and the rocking mode of

appears in the region of 398–417 cm

−1 [

27,

28]. Inequality (16) was proposed on the basis of reported data [

27]; consequently, in

Figure 1b, the vibrations of the

bonds appear in the range of 598–811 cm

−1. Turning now to

bonds, crystals of chromium (III) sulfate interact with interstitial water, and a

bond is formed; it was previously noted that this spectral region becomes visible in the range of 400–600 cm

−1. This suggests that the position of the band corresponding to the

bond in chromium (III) sulfate (

Figure 1b) is lower than 598 cm

−1. Thus, the broad band in the spectrum of chromium (III) sulfate (

Figure 1b) is produced by the convolution of water bands, and the bands are related to

bonds. To support this claim, the bands observed in the range of 550–580 cm

−1 were assigned to

stretching in vibrational studies [

27], whereas the bands at 526–540 cm

−1 were assigned to

bonds [

27]. In the case of the cis isomer band, assignment must consider the mass of the carbon atoms because the wavenumber (energy or frequency) of the infrared bands depends on the mass of the atoms linked to a chemical bond. A smaller mass of hydrogen atoms implies a higher wavenumber, and conversely, a higher mass of carbon atoms implies a lower wavenumber. Therefore, the strength of the bonds in the compounds can be expected to be in the following order:

where

are the wavenumbers of the bands related to the bonds. The bands related to the vibrations of the

bonds tentatively appear in the range of 598–811 cm

−1, and the bands of the

bonds present at wavenumbers lower than 400–598 cm

−1. Consequently, the bands in the cis isomer associated with

bonds should appear in the spectral region between 598 and 400 cm

−1. This region was also selected on the basis of the data reported by Avalos et al. [

27]; for example, the

antisymmetric or symmetric vibrations can be distinguished from the symmetric stretching vibrational modes associated with the

bonds [

27]. Then, inequality (17) is based on the idea that terminal (

) bonds and bridge

bonds can be distinguished for

in the cis isomers.

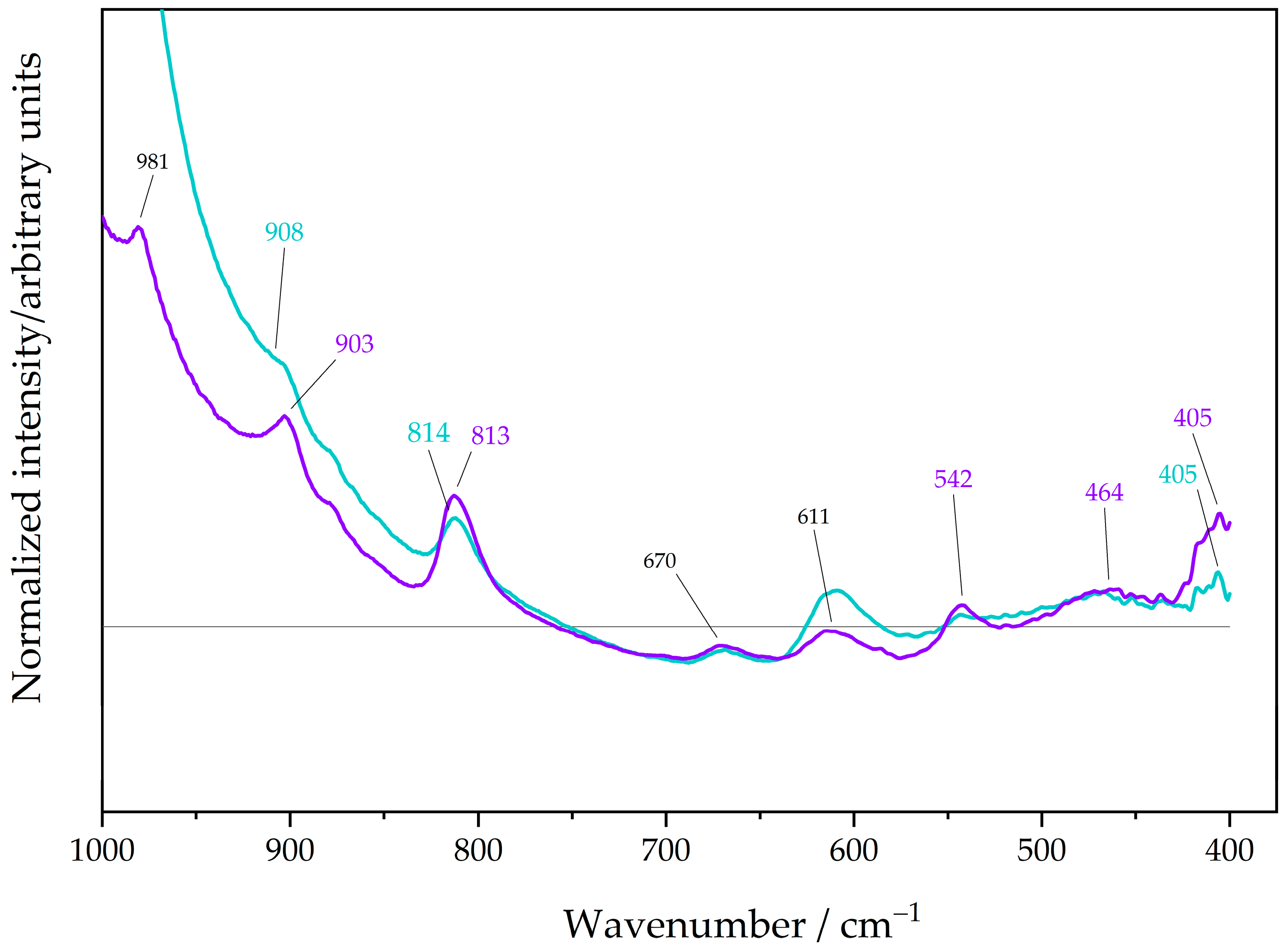

With the above in mind, the observed bands in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 were assigned to the vibrational modes of the bands in

Table 1. The discussion focused on the spectral region of the bands of the

bonds (

Figure 2), and the complete spectra are presented in

Figure A1.

Figure 2 shows that the pH values of solutions containing the cis isomer and chromium (III) sulfate are different. Note that the initial solutions with conductive salts and boric acid have a high ionic strength of 2.055 M, and when chromium (III) sulfate was added to the solution, the ionic strength increased to 7.56 M. Calculating the ionic strength in a solution of the cis isomer was difficult because there are no data in the species of solution. Nevertheless, if the concentration of

is 0.6 M, then the ionic strength could be greater than 4.755 M. Note that the concentrations of species on the speciation diagrams are gross estimates because they were calculated at zero ionic strength. Nonetheless, the speciation diagrams calculated by Conde et al. [

29] suggest which anions and cations are predominant in solutions. In the solution of chromium (III) sulfate, the predominant species are

(100%),

(96%),

(4%),

(1%),

(88%), and

(11%) (cyan line in

Figure 2). Conversely, in the cis isomer solution, the predominant species are

(100%),

(14%),

(86%),

(52%),

(47%), and

(1%) (violet line in

Figure 2). Under these conditions, cations and anions are expected to interact strongly through Coulombic forces, and the formation of ion pairs, hydrogen bonds between solvation spheres of neighboring ions, or inner-sphere complexes would be possible. However, the difference in the concentrations of oxalate and sulfate anions explains the difference in the intensities of the bands in

Figure A1, but the positions of these bands are equal. The bands at 981, 670, and 611 cm

−1 are related to bonds in sulfate and borate compounds, and these positions are labeled with black font in

Figure 2. These bands will be analyzed in future research, and

Table 1 compares the band positions of compounds related to bonds that include chromium, oxygen, and carbon atoms. In

Figure 2, both the cis isomer and chromium (III) sulfate species present bands corresponding to

bonds (

Table 1). The bands related to bridged

bonds are noticeable in the cis isomer species in solution but very narrowly observable in chromium (III) sulfate in solution. In

Figure 1a, the band of the cis isomer crystals at 806 cm

−1 has a slight intensity compared with the bands in the range of 400–600 cm

−1; conversely, in the cis isomer in solution, the band at 806 cm

−1 is more intense than the bands in this range, except for the band at 405 cm

−1. This suggests that the number of

bonds is greater than the number of bridging

bonds in the cis isomer in solution. In the case of chromium (III) sulfate, the bridges

are barely detectable, which suggests that the concentration of the inner-sphere complex is insignificant in these solutions. The relative ratio of the intensities in

Figure 1b between the oxalate band and the bands of

bonds is approximately 1:1; however, in

Figure A1b, oxalate bands are clearly observed, whereas the bands of

bonds are hard to detect. This reaffirms that the concentration of the inner-sphere complex must be very low.

4. Discussion

In the inner-sphere complex hypothesis, the central idea is the formation of

. This postulate suffers from a number of disadvantages listed above, and in our study, this hypothesis is tested via the infrared spectra method. The

compound was synthesized as a probe molecule because this cis isomer contains

bonds, which are the expected bonds formed in the inner complex. This molecule is abbreviated as a cis isomer and has a terminal bond (

), which can be compared to similar bonds of oxides of

or

. Data from our previous study were used for the identification of the spectral region of the bands of the bridge

bonds [

27]. In addition, the experimental spectra of potassium dichromate crystals and chromium (III) sulfate crystals (

Figure 1b) also assisted in band assignment. Posteriorly, the spectra of the solutions containing the cis isomer and chromium (III) sulfate revealed that the number of bridging

bonds was lower in the cis isomer solution, and in the solutions containing chromium (III) sulfate, the number was much lower. Conversely, the intensity of the bands at 813–814, 903, and 908 cm

−1 in

Figure 2 revealed that the terminal bonds (

in

Table 1) are the most numerous bonds in the

species. The bands at 405, 412, 542, and 555 cm

−1 (

Table 1) could be attributed to the bond structure (

); however, this band can also be assigned to the monomer (528 cm

−1), dimer (472 cm

−1) or trimer (481 cm

−1) of the

[

13]. These positions of the infrared bands were reported by Zhang et al. [

13], but the spectra were not included. More vibrational spectroscopy studies are needed to determine the species of

in solutions with high ionic strength. However, our study is the first to address this demand. Given the above, the inner-sphere complex hypothesis does not provide a plausible explanation for the trivalent chromium electrodeposition process.

Conde et al. [

29] obtained a coating with a hardness of 685.7 HV and a thickness of approximately 10 µm using the chromium (III) sulfate bath presented in

Figure 2. The pH of the bath was in the range of 3.2–3.5, which is close to the pH of the solution shown in

Figure 2 (pH 3.36), but the faradaic efficiency was much lower (2–4%).

Figure 2 explains the low current efficiency observed in the study of Conde et al. [

29]; because the band at 542 cm

−1 of

bonds is absent or because this band has a very low intensity. In the literature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], the bath parameters evaluated were the concentration of additives, preparation temperature, and pH. The speciation was investigated by UV–Vis spectroscopy, which is not able to discriminate between oligomers or inner complexes or ion pairs. Consequently, it is not possible to establish a correlation between the species in the bath and their impact on the properties and quality of the coatings. The approach of the trial-and-error method focuses on the quality of the coating obtained after electrodeposition, without the knowledge of why that bath allows that quality. Conversely, our study shows for the first time that vibrational spectroscopy is a definite technique for understanding the electrodeposition process.

In solutions of pure

or aqueous media with other components (inorganic salt or acid), every

ion is surrounded by four regions of solvent: an innermost region of 6 immobilized water molecules [

30], an intermediate structure-broken region with 12 water molecules [

30], a third hydration shell with 20 sites that can be occupied by protons [

30], and an outer region containing water with a normal water bulk structure. The solvation of

in solutions at high ionic strengths is unknown, but a gross estimation is presented below. In one liter of electroplating bath, there is a high concentration of several ions (approximately the sum is 2 M) and an obviously high content of water (56.6 M); thus, there are approximately 25 molecules of water for each ion. This scenario implies that only two hydration shells of

can be formed, and the formation of an ion pair between

and anionic

is probable. Owing to the high stability of

, it is highly probable that the electrostatic attraction between anion

and cation

formed an ion pair. In addition, it is plausible that the water in the solvation shell of

formed hydrogen bonds with

, and this structure prevents the formation of oligomers of

, which are formed via reactions (6)–(9). This new assumption is expected to be evaluated in future research.

Infrared spectroscopy is usually used to characterize the quality of a coating; for example, Kus et al. [

31] reported that the coating was hydrated immediately after electrodeposition or during exposure to open air. However, the bath after electrodeposition was not characterized via infrared spectroscopy. Our study highlighted that infrared spectroscopy provides a profound understanding of the electroplating bath, and we believe that normalized FTIR-ATR spectra could be used as a standard method to characterize the electroplating bath.

Since 1990, approximately one thousand articles have been published on chromium coatings. These coatings can be produced via chemical or electrochemical methods. However, Avalos et al. [

27] found only 76 articles that used vibrational spectroscopy to analyze the coatings. Only three studies have used vibrational spectroscopy to determine the species in trivalent baths [

22,

23,

24]. However, the infrared spectra reported in these studies do not include the region between 500 and 1000 cm

−1, which is in the zone where bands of

bonds appear. Consequently, the relationship between the species in the solutions and their impact on the properties of the trivalent chromium coatings remains unsolved. Our study provides a new approach to determine this correlation, and a relationship between the bath composition and the properties of the coating during the electrodeposition of the cis isomer is expected to be established in the future.

Importantly, the interaction between the additives and Cr(III) can be characterized as follows: (1) Ion pair association: the anions form hydrogen bonds with the water of the coordination sphere of the Cr(III) ion,

. This ion pair is also referred to as the outer-sphere complex. (2) In the inner-sphere complex: the anion becomes more tightly bound and replaces a water molecule from the

coordination sphere.

Figure 2 suggests that inner-sphere complexes are not significantly concentrated; that is, the number of complexes is too low to affect the system being studied. Consequently, this study opens a new hypothesis in which the first step of the electrodeposition process is the formation of ion pairs. Further data and spectra collection are needed to reach a conclusion; however, our study has devised a methodology to obtain reliable evidence. Reactions similar to reaction (17) should occur in the preparation of an electroplating bath, and in this case, the formation of oligomers is avoided by the presence of additives such as oxalate or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (

Appendix B). This reaction is postulated because, in a solution of chromium (III) sulfate, the predominant species are

(88%).

Reaction (18) shows the constants of the protonation/deprotonation reactions of the

species, and additives are a priority parameter of the electrodeposition process. Thus, reaction (17) is predominant at pH values inferior to pKa (4.23) of reaction (4) [

21].

Appendix B summarizes the possible sequence of steps for the formation of chromium coatings. Future research on electrodeposition from

needs to distinguish between inner- and outer-sphere electrode reaction mechanisms.