A Smart AIoT-Based Mobile Application for Plant Disease Detection and Environment Management in Small-Scale Farms Using MobileViT

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- For plant disease detection, the lightweight MobileViT network, combining transformer and convolution blocks, was utilized resulting in enhanced performance compared to several state-of-the-art models from literature.

- (2)

- For plant environment management, the powerful, budget-friendly ESP32 microcontroller was utilized as the core processing unit, collecting sensor data, controlling actuators, and maintaining connectivity with Google Firebase Cloud to allow real-time and remote system monitoring and control.

2. Related Works

| Plant Disease Detection | Chatbot | IoT | Mobile App | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset (Crops) | Model | Accuracy | ||||

| Shrimali [15] | PV (14) | MobileNetV2 | 95.70% |  |  |  |

| Tembhurne et al. [16] | PV & others (22) | MobileNetV2 | 96.00% |  |  |  |

| Garg et al. [17] | PV (14) | MobileNetV2 | 96.72% |  |  |  |

| Tyagi et al. [18] | Rice | CNN | 99.00% |  |  |  |

| Borhani et al. [19] | PV (14) | CNN | 90.00% |  |  |  |

| Transformer | 95.00% | |||||

| Hybrid | 93.00% | |||||

| Tabbakh and Barpanda [20] | Wheat | VGG + ViT | 99.86% |  |  |  |

| PV (2) | 98.81% | |||||

| Baek [21] | Apple Grape Tomato | Multi-ViT | 99.12% 99.49% 96.69% |  |  |  |

| Nishankar et al. [22] | Tomato | Swin ViT | 99.04% |  |  |  |

| Barman et al. [23] | PV (1) | ViT | 90.99% |  |  |  |

| Li et al. [27] | Wheat | MobileViT with CBAM & inverted residual blocks | 93.60% |  |  |  |

| Coffee | 85.40% | |||||

| Rice | 93.10% | |||||

| Zhang et al. [28] | Rice | MobileViT with dual attention | 99.61% |  |  |  |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. MobileNet

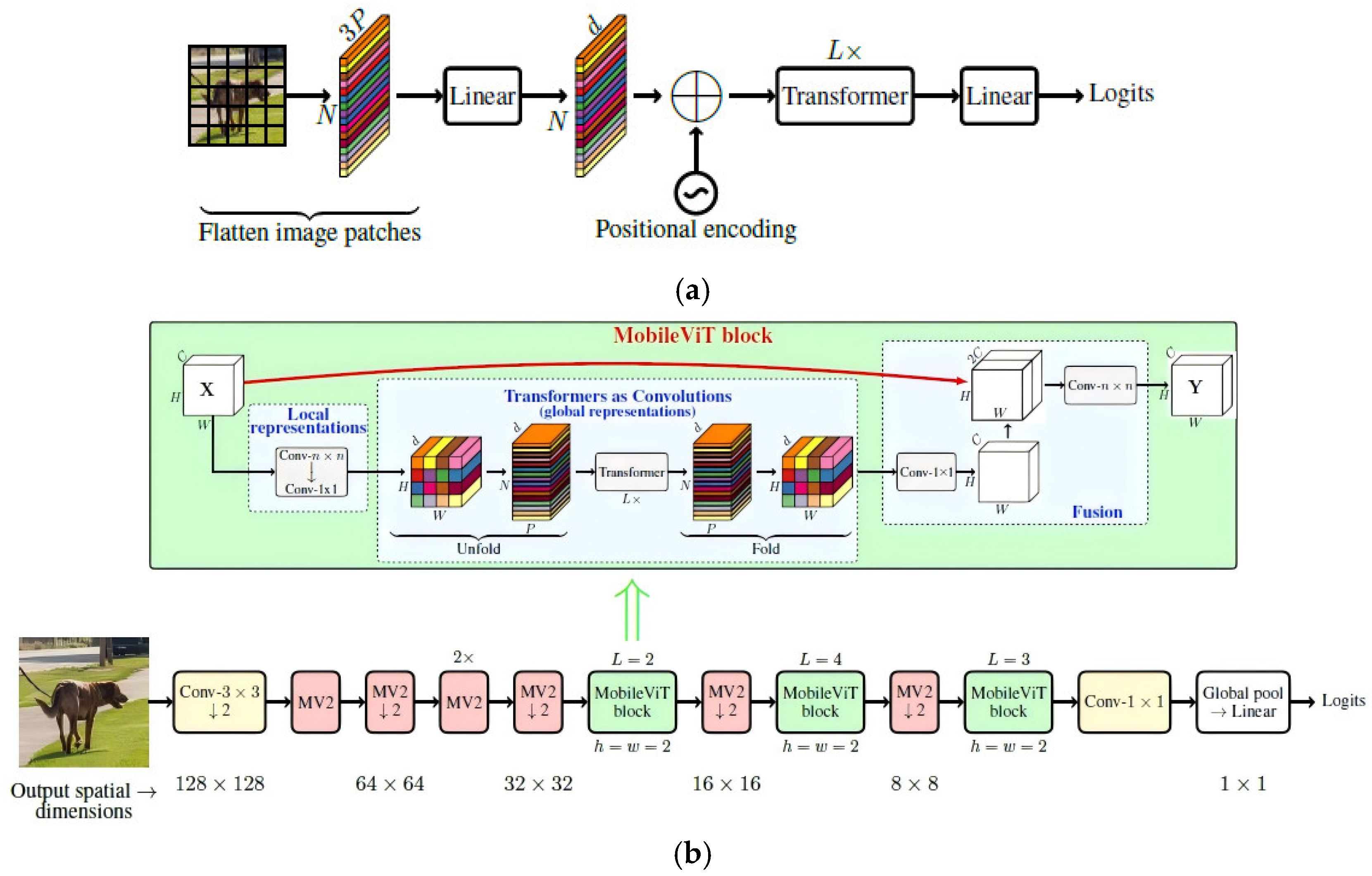

3.4. MobileViT

3.5. Experimental Setup

4. System Design

- (a)

- AI-based plant disease detection and LLM-powered interactive chatbot.

- (b)

- IoT-based plant environment management (monitoring and control).

4.1. LLM-Powered Chatbot

4.2. IoT-Based Plant Management System

| Algorithm 1. Pseudo-code summarizing the operations of the IoT-based plant management system, including sensor data acquisition, Firebase cloud synchronization, and actuator control |

| BEGIN 1: Initialize Firebase, Wi-Fi, sensors, and actuators 2: WHILE TRUE DO 3: Read all sensor data (temperature & humidity, light, soil moisture, flame, smoke) 4: Upload all sensor data to Firebase 5: IF manual command received from Firebase THEN 6: Control actuators accordingly (fan–pump) 7: ELSE IF predefined thresholds are exceeded THEN 8: Control actuators automatically: turn water pump on for low soil moisture, 9: turn fan on for high temperatures, trigger alarm if flame or smoke is detected 10: END IF 11: Wait for predetermined time interval 12: END WHILE END |

4.3. User Interface

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Plant Disease Detection Results

5.1.1. Leaf vs. Non-Leaf Classification

5.1.2. Plant Disease Classification

5.2. Mobile Application

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIoT | Artificial Intelligence of Things |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| HTTPS | Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation file |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| MV2 | MobileNetV2 |

| PV | Plant Village Dataset |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| SE | Squeeze and Excitation |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Global Agriculture Towards 2050; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Sánchez, M.V.; Bertini, R. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Dev. 2021, 142, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Yadav, A.; Panme, F.A.; Devi, K.M.; Kumar, S.M.S. Adaption of smart applications in agriculture to enhance production. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Demilie, W.B. Plant disease detection and classification techniques: A comparative study of the performances. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaisi, K.S.; Ye, Q.; Sampalli, S. A Survey of Industrial AIoT: Opportunities, Challenges, and Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 96946–96996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, D.; Ahvar, E.; Ahvar, S.; Trocan, M.; Montpetit, M.-J.; Ehsani, R. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for smart agriculture: A review of architectures, technologies and solutions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 228, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelaios, D.; Theofilou, P.-A.; Tzouveli, P.; Kollias, S. Hybrid CNN-ViT Models for Medical Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Athens, Greece, 27–30 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurício, J.; Domingues, I.; Bernardino, J. Comparing Vision Transformers and Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Li, F.F. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrimali, S. PlantifyAI: A Novel Convolutional Neural Network Based Mobile Application for Efficient Crop Disease Detection and Treatment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 191, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembhurne, J.V.; Gajbhiye, S.M.; Gannarpwar, V.R.; Khandait, H.R.; Goydani, P.R.; Diwan, T. Plant disease detection using deep learning based Mobile application. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 27365–27390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, G.; Gupta, S.; Mishra, P.; Vidyarthi, A.; Singh, A.; Ali, A. CROPCARE: An Intelligent Real-Time Sustainable IoT System for Crop Disease Detection Using Mobile Vision. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 2840–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Reddy, S.R.N.; Anand, R.; Sabharwal, A. Enhancing rice crop health: A light weighted CNN-based disease detection system with mobile application integration. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 48799–48829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, Y.; Khoramdel, J.; Najafi, E. A deep learning based approach for automated plant disease classification using vision transformer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabbakh, A.; Barpanda, S.S. A Deep Features Extraction Model Based on the Transfer Learning Model and Vision Transformer ‘TLMViT’ for Plant Disease Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45377–45392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, E.-T. Attention Score-Based Multi-Vision Transformer Technique for Plant Disease Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishankar, S.; Pavindran, V.; Mithuran, T.; Nimishan, S.; Thuseethan, S.; Sebastian, Y. ViT-RoT: Vision Transformer-Based Robust Framework for Tomato Leaf Disease Recognition. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, U.; Sarma, P.; Rahman, M.; Deka, V.; Lahkar, S.; Sharma, V.; Saikia, M.J. Vit-SmartAgri: Vision transformer and smartphone-based plant disease detection for smart agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Singh, M.; Mintun, E.; Darrell, T.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Early convolutions help transformers see better. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 30392–30400. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: Light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.02178. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Separable Self-attention for Mobile Vision Transformers (MobileViTv2). arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02680. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, P.; Chang, B. PMVT: A lightweight vision transformer for plant disease identification on mobile devices. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1256773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, Z.; Tang, S.; Lin, C.; Zhang, L.; Dong, W.; Zhong, N. Dual-Attention-Enhanced MobileViT Network: A Lightweight Model for Rice Disease Identification in Field-Captured Images. Agriculture 2025, 15, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Salathé, M. An open access repository of images on plant health to enable the development of mobile disease diagnostics. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.08060. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Plant Village. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/abdallahalidev/plantvillage-dataset (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- TensorFlow. ImageDataGenerator. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/api_docs/python/tf/keras/preprocessing/image/ImageDataGenerator (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Elaziz, M.A.; Al-Qaness, M.A.A.; Dahou, A.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Abualigah, L.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Ewees, A.A. Evolution toward intelligent communications: Impact of deep learning applications on the future of 6G technology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14, e1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. and others Chollet. Keras. Available online: https://keras.io (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- MobileViT_XXS. Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/timm/mobilevit_xxs.cvnets_in1k (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Singh, S.U.; Namin, A.S. A survey on chatbots and large language models: Testing and evaluation techniques. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2025, 10, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Tong, Q. LLM-Powered AI Agent Systems and Their Applications in Industry. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.16120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espressif Systems. ESP32 Microcontroller. Available online: https://www.espressif.com/en/products/socs/esp32 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Google. Firebase. Available online: https://firebase.google.com/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Google. Firebase Realtime Database. Available online: https://firebase.google.com/products/realtime-database (accessed on 21 March 2025).

| Name | Function | Type |

|---|---|---|

| YL-69 | Soil Moisture | Sensor |

| DHT11 | Temperature & Humidity | Sensor |

| MQ-2 | Smoke & Gas Detection | Sensor |

| Flame Sensor | Flame Detection | Sensor |

| BH1750 | Light Intensity | Sensor |

| Water pump | Irrigation | Actuator |

| Fan | Ventilation | Actuator |

| Buzzer | Fire alarm | Actuator |

| Plant Species_Health | Prec. | Rec. | F1-Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apple___Apple_scab | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| 2 | Apple___Black_rot | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3 | Apple___Cedar_apple_rust | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4 | Apple___healthy | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 5 | Blueberry___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6 | Cherry_(including_sour)___Powdery_mildew | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 7 | Cherry_(including_sour)___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8 | Corn_(maize)___Cercospora_leaf_spot Gray_leaf_spot | 0.85 | 0.9 | 0.88 |

| 9 | Corn_(maize)___Common_rust_ | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| 10 | Corn_(maize)___Northern_Leaf_Blight | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| 11 | Corn_(maize)___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 12 | Grape___Black_rot | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 13 | Grape___Esca_(Black_Measles) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 14 | Grape___Leaf_blight_(Isariopsis_Leaf_Spot) | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 15 | Grape___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 16 | Orange___Haunglongbing_(Citrus_greening) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 17 | Peach___Bacterial_spot | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 18 | Peach___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 19 | Pepper,_bell___Bacterial_spot | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20 | Pepper,_bell___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 21 | Potato___Early_blight | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 22 | Potato___Late_blight | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 23 | Potato___healthy | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| 24 | Raspberry___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25 | Soybean___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 26 | Squash___Powdery_mildew | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 27 | Strawberry___Leaf_scorch | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 28 | Strawberry___healthy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 29 | Tomato___Bacterial_spot | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 30 | Tomato___Early_blight | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| 31 | Tomato___Late_blight | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| 32 | Tomato___Leaf_Mold | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 33 | Tomato___Septoria_leaf_spot | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 34 | Tomato___Spider_mites Two-spotted_spider_mite | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 35 | Tomato___Target_Spot | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| 36 | Tomato___Tomato_Yellow_Leaf_Curl_Virus | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 37 | Tomato___Tomato_mosaic_virus | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 38 | Tomato___healthy | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Model | Params. | Acc. % | Prec. % | Rec. % | AUC % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NasNetMobile | 5.3M | 93.18 | 94.54 | 92.30 | 99.79 |

| MobileNetV1 | 4.3M | 97.50 | 97.72 | 97.36 | 99.85 |

| MobileNetV2 | 3.5M | 96.02 | 96.52 | 95.65 | 99.83 |

| MobileNetV3-Small | 2.5M | 97.88 | 98.05 | 97.78 | 99.92 |

| MobileViT-XXSmall | 1.3M | 99.44 | 99.30 | 99.07 | 1.00 |

| Model | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|

| Shrimali 2021 [15] | Customized | 77.3% |

| VGG | 93.6% | |

| ResNet152 | 87.3% | |

| MobileNetV2 | 95.7% | |

| Borhani et al. 2022 [19] | Convolution-based model | 90.0% |

| Transformer-based model | 95.0% | |

| Hybrid model | 93.0% | |

| Garg et al. 2023 [17] | InceptionV3 | 87.2% |

| ResNet34 | 95.4% | |

| MobileNetV2 | 96.7% | |

| Proposed | MobileViT-XXSmall | 99.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bahaa, M.; Hesham, A.; Ashraf, F.; Abdel-Hamid, L. A Smart AIoT-Based Mobile Application for Plant Disease Detection and Environment Management in Small-Scale Farms Using MobileViT. AgriEngineering 2026, 8, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010011

Bahaa M, Hesham A, Ashraf F, Abdel-Hamid L. A Smart AIoT-Based Mobile Application for Plant Disease Detection and Environment Management in Small-Scale Farms Using MobileViT. AgriEngineering. 2026; 8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahaa, Mohamed, Abdelrahman Hesham, Fady Ashraf, and Lamiaa Abdel-Hamid. 2026. "A Smart AIoT-Based Mobile Application for Plant Disease Detection and Environment Management in Small-Scale Farms Using MobileViT" AgriEngineering 8, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010011

APA StyleBahaa, M., Hesham, A., Ashraf, F., & Abdel-Hamid, L. (2026). A Smart AIoT-Based Mobile Application for Plant Disease Detection and Environment Management in Small-Scale Farms Using MobileViT. AgriEngineering, 8(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010011