Humic Substance Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate of a Landfill Leachate Treatment via Nanofiltration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reverse Osmosis Concentrate

2.2. Nanofiltration

2.3. Germination Test with Recovered Humic Substances

2.4. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Leachate Concentrate

- Recalcitrant organic compounds: The Seropédica landfill leachate presents a high concentration of recalcitrant organic compounds, with an average humic substance concentration of 1935 mg/L [25]. The low biodegradability evidenced in the leachates of the landfills studied is the absorbance at 254 nm value. The absorbance at 254 nm value is related to aromatic organic compounds, such as humic substances [32]. A high absorbance value at 254 nm is observed in the leachate of the Seropédica landfill (31.5) [31]. The parameter color can be associated with dissolved substances, confirmed by the high concentration of humic substances.

- Ammonia nitrogen: Concentrations in the range of 2104–2231 mg/L were described by [3] for Seropédica landfill leachate. High concentrations of ammonia nitrogen are found in leachates as a product of the degradation of waste protein and can constitute 0.5% of the dry mass of waste. The ammonia nitrogen remains high, as can chloride and alkalinity concentrations in leachates from mature landfills. Therefore, it is considered one of the main pollutants of leachate [33].

3.2. Nanofiltration Performance

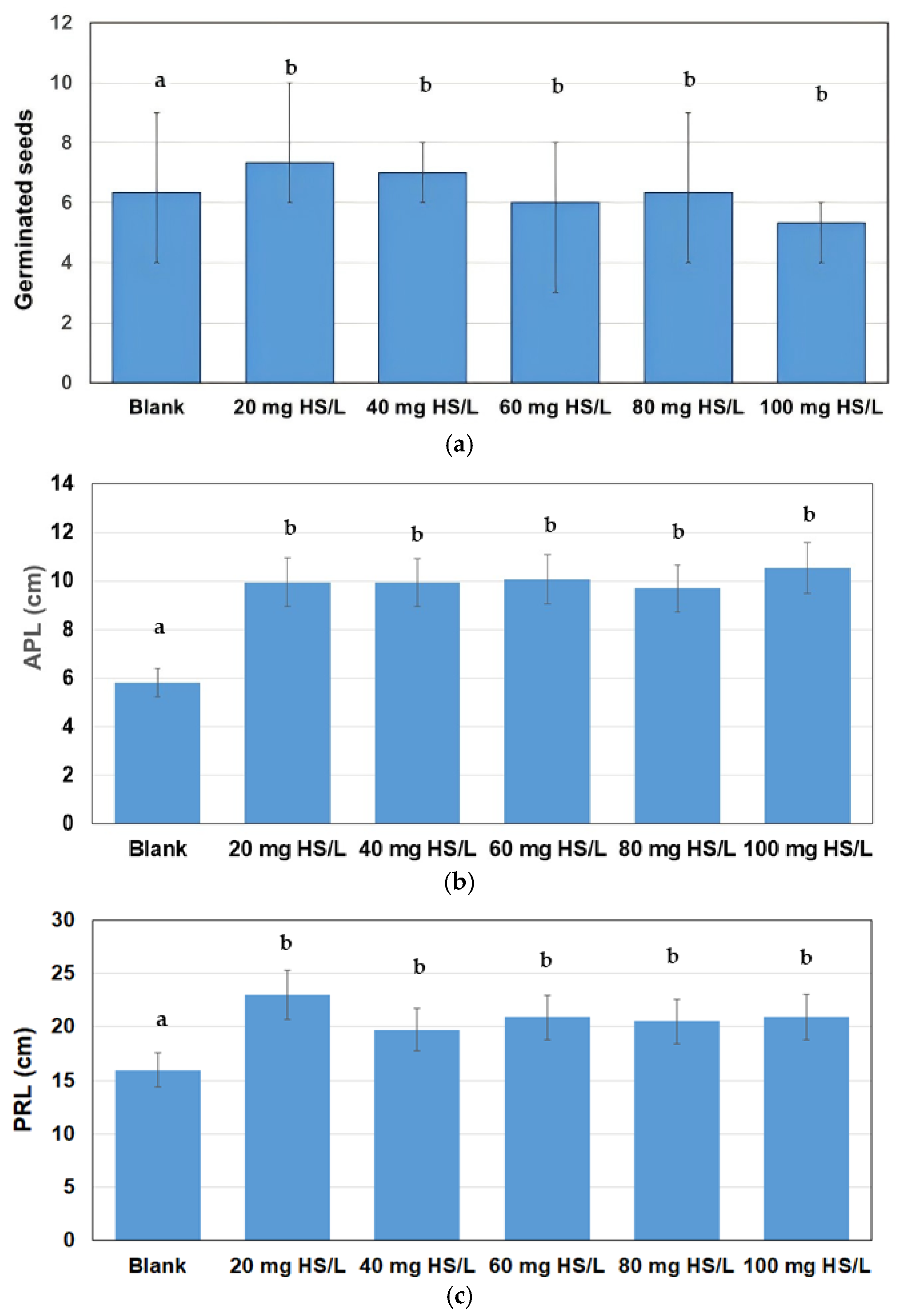

3.3. Germination Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfaia, R.G.S.M.; Costa, A.M.; Campos, J.C. Municipal solid waste in Brazil: A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2017, 35, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renou, S.; Givaudan, J.G.; Poulain, S.; Dirassouyan, F.; Moulin, P. Landfill leachate treatment: Review and opportunity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 150, 468–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.M.; Alfaia, R.G.S.M.; Campos, J.C. Landfill leachate treatment in Brazil—An overview. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, L.; Roddick, F.A. Influence of the characteristics of soluble algal organic matter released from Microcystis aeruginosa on the fouling of a ceramic microfiltration membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 425, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossou, K.; Prasad, S.B.; Agbotsou, K.E.; Souley, H.S.; Mudigandla, R. Characteristics of landfill leachate and leachate treatment by biological and advanced coagulation process: Feasibility and effectiveness—An overview. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Zhong, C.; Liu, M.; Yang, L.; He, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, D. Treatment of landfill leachate by coagulation: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, T.; Nghiem, L.D. Landfill leachate tretment using hybrid coagulation-nanofiltration processes. Desalination 2010, 250, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaia, R.G.S.M.; de Almeida, R.; Nascimento, K.S.; Campos, J.C. Landfill leachate pre-treatment effects on nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membrane performance. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 172, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Porto, R.F.; Quintaes, B.R.; Bila, D.M.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Campos, J.C. A review on membrane concentrate management from landfill leachate treatment plants: The relevance of resource recovery to close the leachate treatment loop. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABREMA—Brazilian Association of Solid Waste and Environment. Available online: https://www.abrema.org.br/2020/12/14/aterro-sanitario-seropedica-regiao-metropolitana-do-rio-de-janeiro/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- AST Ambiente. Available online: https://ast-ambiente.com.br/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Gu, N.; Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Chang, N.; Li, Y. Bioenergy, ammonia and humic substances recovery from municipal solid waste leachate: A review and process integration. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.L.; Shimaoka, T.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y.C. Characterization of humic and fulvic acids extracted from landfill by elemental composition, 13C CP/MAS NMR and TMAH-PY-GC/MS. Waste Manag. 2007, 28, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Campos, J.C. Technoeconomic analysis of landfill leachate treatment. Rev. Ineana. 2022, 8, 6–27. Available online: https://www.inea.rj.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Revista-ineana-8.1.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y. Maize (Zea mays) growth and nutrient uptake following integrated improvement of vermi compost and humic acid fertilizer on coastal saline soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Mostofa, K.M.G.; Mohinuzzaman, M.; Teng, H.H.; Senesi, N.; Senesi, G.S.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.-L.; et al. Solubility characteristics of soil humic substances as a function of pH: Mechanisms and biogeochemical perspectives. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 1745–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Liu, H.; Jiang, M.; Lin, J.; Ye, K.; Fang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhai, S.; Van der Bruggen, B.; He, Z. Sustainable management of landfill leachate concentrate through recovering humic substance as liquid fertilizer by loose nanofiltration. Water Res. 2019, 157, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, X.K.; Chen, C.L.; Zhou, X.; Tan, X.L. Influence of soil humic acid and fulvic acid on sorption of thorium(IV) on MX-80 bentonite. Radiochim. Acta 2006, 94, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Hou, D.; Wu, X.; Li, K.; Wang, J. Fenton pre-treatment to mitigate membrane distillation fouling during treatment of landfill leachate membrane concentrate: Performance and mechanism. Water Res. 2023, 244, 120517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wan, Y.; Chen, X.; Luo, J. Loose nanofiltration membrane custom-tailored for resource recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 409, 127376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciclus Ambiental. Available online: https://ciclusambiental.com.br/#solucoes (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- APHA (American Public Health Association); AWWA (American Water Works Association); WEF (Water Environment Federation). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; 1360p. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Zhang, M.; Yu, H. A rapid quantitative method for humic substances determination in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 592, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sir, M.; Podhola, M.; Patocka, T.; Honzajkova, Z.; Kocurek, P.; Kubal, M.; Kuras, M. The effect of humic acids on the reverse osmosis treatment of hazardous landfill leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 207–208, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.S.M.S.; De Almeida, R.; Quintaes, B.R.; Bila, D.M.; Campos, J.C. Evaluation of humic substances removal from leachates originating from solid waste landfills in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2017, 52, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.; Pasaoglu, M.E.; Guclu, S.; Turken, T.; Yildiz, S.; Balahorli, V.; Koyuncu, I. Foulant and chemical cleaning analysis of ultrafiltration membrane used in landfill leachate treatment. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 77, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Couto, J.M.C.; Gouvea, R.M.; Oroski, F.A.; Bila, D.M.; Quintaes, B.R.; Campos, J.C. Nanofiltration applied to the landfill leachate treatment and preliminary cost estimation. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA—Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply. Legislation. 2009. Available online: www.agricultura.gov.br (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Aylaj, M.; Adani, F. The evolution of compost phytotoxicity during municipal waste and poultry manure composting. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Porto, R.F.; Hinojosa, M.A.G.; Sanches, L.C.M.; Monteiro, B.B.; Conde, A.L.F.M.; Costa, A.M.; Quintaes, B.R.; Bila, D.M.; Campos, J.C. Monitoring of experimental landfill cells with membrane concentrate infiltration: A systematic assessment of leachate quality and treatment performance. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.M.; Daflon, S.D.A.; Campos, J.C. Landfill Leachate and Ecotoxicity. In A Review of Landfill Leachate; Anouzla, A., Souabi, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvenc, S.Y.; Varank, G. Degradation of refractory organics in concentrated leachate by the Fenton process: Central composite design for process optimization. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, B.; Merlin, G. The contribution of ammonia and alkalinity to landfill leachate toxicity to duckweed. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 170, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fadel, M.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Chahine, W.; Alayli, B. Temporal variation of leachate quality from pre-sorted and baled municipal solid waste with high organic and moisture content. Waste Manag. 2002, 22, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Costa, A.M.; Oroski, F.A.; Campos, J.C. Evaluation of coagulation–flocculation and nanofiltration processes inlandfill leachate treatment. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2019, 54, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, S.; Chang, C.C.H.; Wu, T.Y.; Chai, S. The study of reverse osmosis on glycerin solution filtration: Dead-end and crossflow filtrations, transport mechanism, rejection and permeability investigations. Desalination 2014, 352, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Hong, M.; Huang, X.; Chen, T.; Gu, A.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Seo, D.H.; Zhao, S.; et al. Towards effective recovery of humate as green fertilizer from landfill leachate concentrate by electro-neutral nanofiltration membrane. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Z.; Du, Z.; Wu, D. Potential effect of biogas slurry application to mitigate of peak N2O emission without compromising crop yield in North China Plain cropping systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 210, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ding, Z.; Ali, E.F. Biochar and compost enhance soil quality and growth of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) under saline conditions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Zhou, J.; Han, L.; Ma, S.; Sun, X.; Huang, G. Role and multi-scale characterization of bamboo biochar during poultry manure aerobic composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Shutao, W.; Jin, Z.; Tong, X. Biochar influences the microbial community structure during tomato stalk composting with chicken manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 154, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Tian, G.; Liang, X. Phytotoxicity and speciation of copper, zinc and lead during the aerobic composting of sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 163, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiquia, S. Reduction of compost phytotoxicity during the process of decomposition. Chemosphere 2010, 79, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. National Environment Council (CONAMA). Resolution 357: Classification of the Water Bodies and Environmental Guidelines. 2005. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?id=450&option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download (accessed on 25 October 2025).

| Parameter | Mean Value | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abs 254 nm (dimensionless) | 208.51 | 204.93 | 216.53 |

| Alkalinity (mgCaCO3/L) | 31,927 | 31,040 | 32,380 |

| TOC—Total Organic Carbon (mgC/L) | 7564 | 7415 | 7713 |

| HS—Humic Substances (mg/L) | 19,671 | 18,995 | 20,427 |

| NH3-N (mg/L) | 10,539 | 10,212 | 11,041 |

| pH | 7.97 | 7.95 | 7.98 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 65.5 | 65.1 | 65.9 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 72.25 | 69.92 | 74.58 |

| Total Solids (mg/L) | 111,155 | 110,030 | 112,280 |

| Total Fixed Solids (mg/L) | 43,670 | 43,580 | 43,760 |

| Total Volatile Solids (mg/L) | 67,485 | 66,270 | 68,700 |

| Cl− (mgCl/L) (*) | 13,161 | - | - |

| Color (mgPtCo/L) (*) | 18,571 | - | - |

| COD—Chemical Oxygen Demand (mgO2/L) (*) | 32,872 | - | - |

| Parameter | Mean Value (Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|---|

| Concentrate | Permeate | |

| Abs 254 nm | 315.5 (4.7) | 102.8 (7.7) |

| TOC (mgC/L) | 11,433 (172) | 3239 (48) |

| Chloride (mgCl−/L) | 10,811 (151) | 12,691 (190) |

| Color (mgPtCo/L) | 58,095 (671) | 1905 (28) |

| COD (mgO2/L) | 48,820 (726) | 13,832 (207) |

| NH3-N (mg/L) | 8167 (83) | 8367 (85) |

| pH | 8.2 (0.1) | 8.4 (0.1) |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 57.0 (1.1) | 4.6 (0.1) |

| Humic Substances (mg/L) | 29,763 (444) | 9698 (729) |

| HS Concentration (mg/L) | GR (%) | RL (%) | GI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 115.8 | 144.2 | 167.0 |

| 40 | 110.5 | 123.5 | 136.5 |

| 60 | 100.0 | 130.9 | 130.9 |

| 80 | 94.7 | 128.6 | 121.9 |

| 100 | 84.2 | 131.2 | 110.4 |

| Parameter | CONAMA Resolution 357/2005 [44] * | 100 mg HS/L Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dissolved aluminum (mg/L) | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Total arsenic (mg/L) | 0.033 | 0.001 |

| Total barium (mg/L) | 1.0 | 0.004 |

| Total lead (mg/L) | 0.033 | 0.0012 |

| Chloride (mg/L) | 250 | 22.56 |

| Total cobalt (mg/L) | 0.2 | 0.001 |

| Dissolved iron (mg/L) | 5.0 | 0.09 |

| Total manganese (mg/L) | 0.5 | 0.005 |

| Total mercury (mg/L) | 0.002 | <0.00003 |

| Total zinc (mg/L) | 5.0 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbosa Alves, L.; Alves da Silva, C.E.; Ramalho Quintaes, B.; Carbonelli Campos, J. Humic Substance Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate of a Landfill Leachate Treatment via Nanofiltration. AgriEngineering 2026, 8, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010012

Barbosa Alves L, Alves da Silva CE, Ramalho Quintaes B, Carbonelli Campos J. Humic Substance Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate of a Landfill Leachate Treatment via Nanofiltration. AgriEngineering. 2026; 8(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbosa Alves, Letícia, Carlos Eduardo Alves da Silva, Bianca Ramalho Quintaes, and Juacyara Carbonelli Campos. 2026. "Humic Substance Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate of a Landfill Leachate Treatment via Nanofiltration" AgriEngineering 8, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010012

APA StyleBarbosa Alves, L., Alves da Silva, C. E., Ramalho Quintaes, B., & Carbonelli Campos, J. (2026). Humic Substance Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate of a Landfill Leachate Treatment via Nanofiltration. AgriEngineering, 8(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering8010012