1. Introduction

Measuring the light environment parameters when growing plants in a greenhouse is an important task for predicting crop yields [

1], especially when growing plants under artificial irradiation [

2]. Until recently, high-pressure sodium arc lamps (HPS) were the main sources of artificial irradiation in greenhouses around the world [

3]. Since the spectral composition of HPS radiation is known and does not vary significantly depending on the brand and model of the lamp, inexpensive lux meters were used to measure radiation at the plant level. However, with the introduction of LED technologies in greenhouse vegetable growing, the use of a lux meter introduces significant errors when measuring radiation with different spectral compositions of LED lamps. This is due to the fact that the spectral responsivity of the lux meter correlates with the spectral responsivity of the human eye [

4], since the light quantities are constructed on the basis of the experimentally established dependence of the human eye’s visual perception on the radiation wavelength. To measure the parameters of light sources with different spectral compositions, it is necessary to use energy or photon quantities.

Special photometers are produced that measure photon irradiance using sensors with equal-quantum spectral responsivity in the spectral range of 400–700 nm [

5]. For example, the popular LI-190R quantum sensor measures photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in µmol m

−2 s

−1 over a wavelength range of 400 to 700 nm, which closely matches the light used by most plants [

6]. The main disadvantage of these quantum sensors is their inability to measure spectral components, including the photon flux density of red and blue light ranges, which are widely used for plant illumination. A solution to this problem was proposed by Xinyu Zhang et al. [

7]; to evaluate the PAR, they used two silicon photodiodes as quantum sensors, after passing the light through two bandpass filters with transmission peaks at 450 and 660 nm, which made it possible to obtain the photon flux density of the red and blue spectral ranges. However, this solution is not well suited for modern supplementary lighting systems, which typically use wider spectral ranges.

Recent studies have shown that the 700–750 nm range, being outside the traditional 400–700 nm range, is also photosynthetically active [

8]. Apogee Instruments has released the MQ-610 sensor with responsivity in the 400–750 nm range, corresponding to the extended photosynthetically active ePAR range, including the far-red range [

9]. But in addition to assessing the total photon flux density (PFD), it is also important to understand the spectral distribution of the radiation falling on the plant across the main sub-ranges: blue 400–500 nm, green 500–600 nm, red 600–700 nm and far-red 700–800 nm. The use of complex and expensive spectrometers based on CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) matrices with diffraction gratings for these purposes is not always justified, since when growing plants, there is no need to evaluate the spectral composition of optical radiation with high spectral resolution. Another way to reduce the spectrometer cost is to use spectrometer modules developed using microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology [

10]. For example, Diego Real et al. [

11] presented a design of a data acquisition system for field measurements based on the Hamamatsu C12666MA spectrometer module with a measurement range from 340 nm to 780 nm. Jolyon Troscianko used the Hamamatsu C12880MA spectrometer module with a measurement range from 340 nm to 850 nm when creating a spectrometer [

12]. The use of highly sensitive linear image sensors based on complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) together with MEMS in these devices [

11,

12] makes it possible to obtain high accuracy in a wide spectral range. The main disadvantage is the relatively high cost of spectrometric modules, which complicates the widespread implementation of these devices in greenhouse vegetable growing. Therefore, the development of an inexpensive portable device for assessing irradiation parameters in greenhouse vegetable growing is a pressing issue.

There have been previous attempts to develop devices for PAR measurement based on inexpensive multi-channel sensors [

13]. A recent paper describes the development of a low-cost portable device for measuring PAR and spectral intensity distribution [

14]. However, in these works, the sensor was calibrated only to measure total PAR in the range of 400–700 nm without dividing it into sub-ranges. Moreover, the imperfection of the data processing algorithm leads to measurement error increase on light sources of different spectral composition. Thus, the purpose of this research is to design and validate a low-cost spectroradiometer for measuring PAR and to develop a processing algorithm capable of accurately reconstructing the spectral distribution of unknown light sources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Device Design and General Characteristics

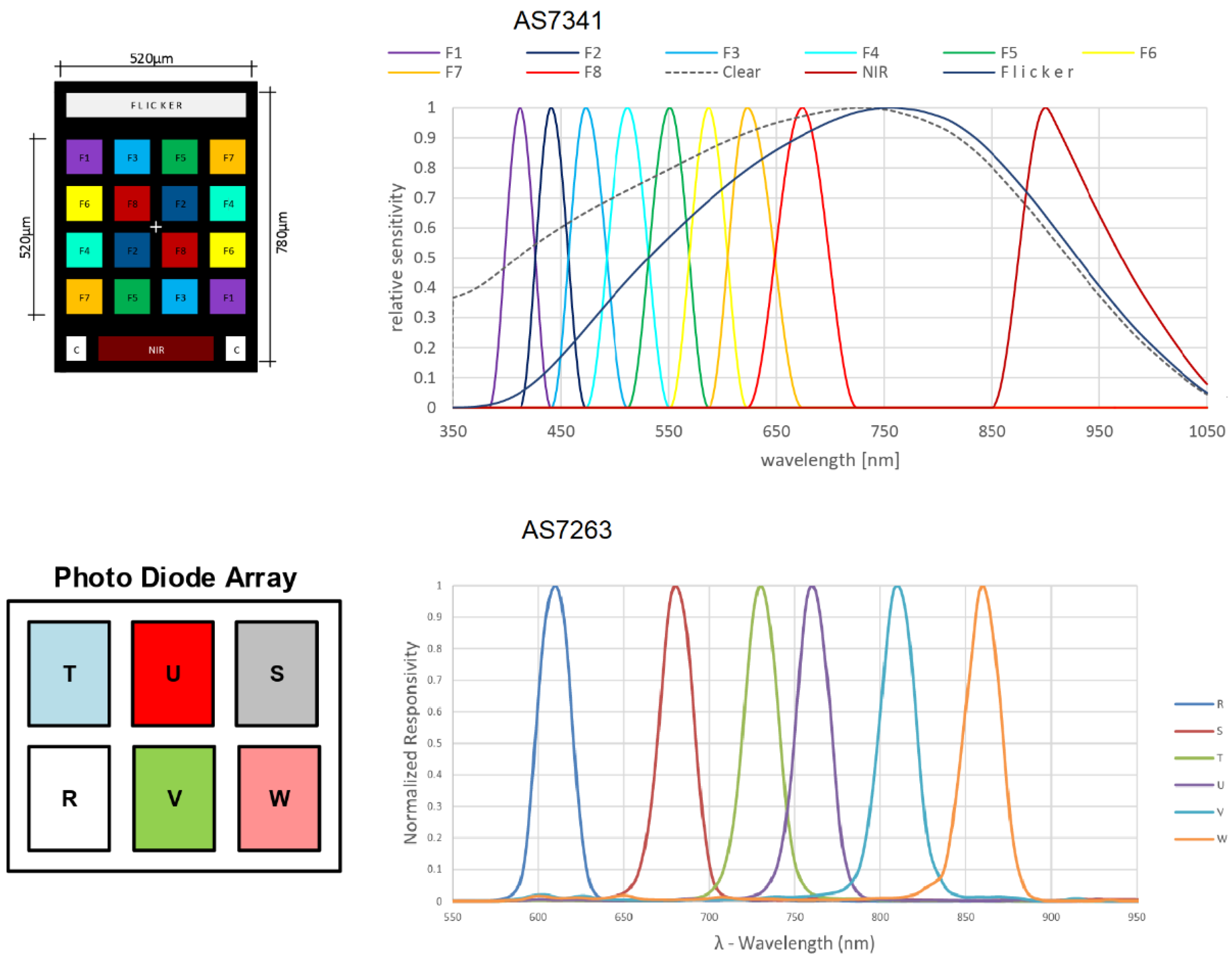

As a basis for a low-cost spectroradiometer, we chose the compact multi-channel spectrometer sensors AS7341 and AS7263 (

Table 1) for spectral identification and color matching, manufactured by AMS, a part of the OSRAM group (Austria, Europe). These sensors consist of photodiode arrays with filters. The AS7341 sensor has a spectral response in the wavelength range from approximately 350 nm to 1000 nm (

Figure 1). 8 visible light spectral channels with declared responsivity peaks at wavelengths of 415, 445, 480, 515, 555, 590, 630, 680 nm and one near-infrared channel with declared responsivity peak of 900 nm, as well as general brightness and flicker sensors, not used in this algorithm for the reasons given below. Access to control and spectral analysis data is provided via the I

2C serial interface. The device is housed in an ultra-slim housing with dimensions 3.1 mm × 2 mm × 1 mm. The AS7263 sensor is a digital 6-channel spectrometer for far-red and near-infrared spectral identification. It consists of six independent optical filters with spectral response determined in the red and near-infrared ranges from approximately 600 nm to 870 nm.

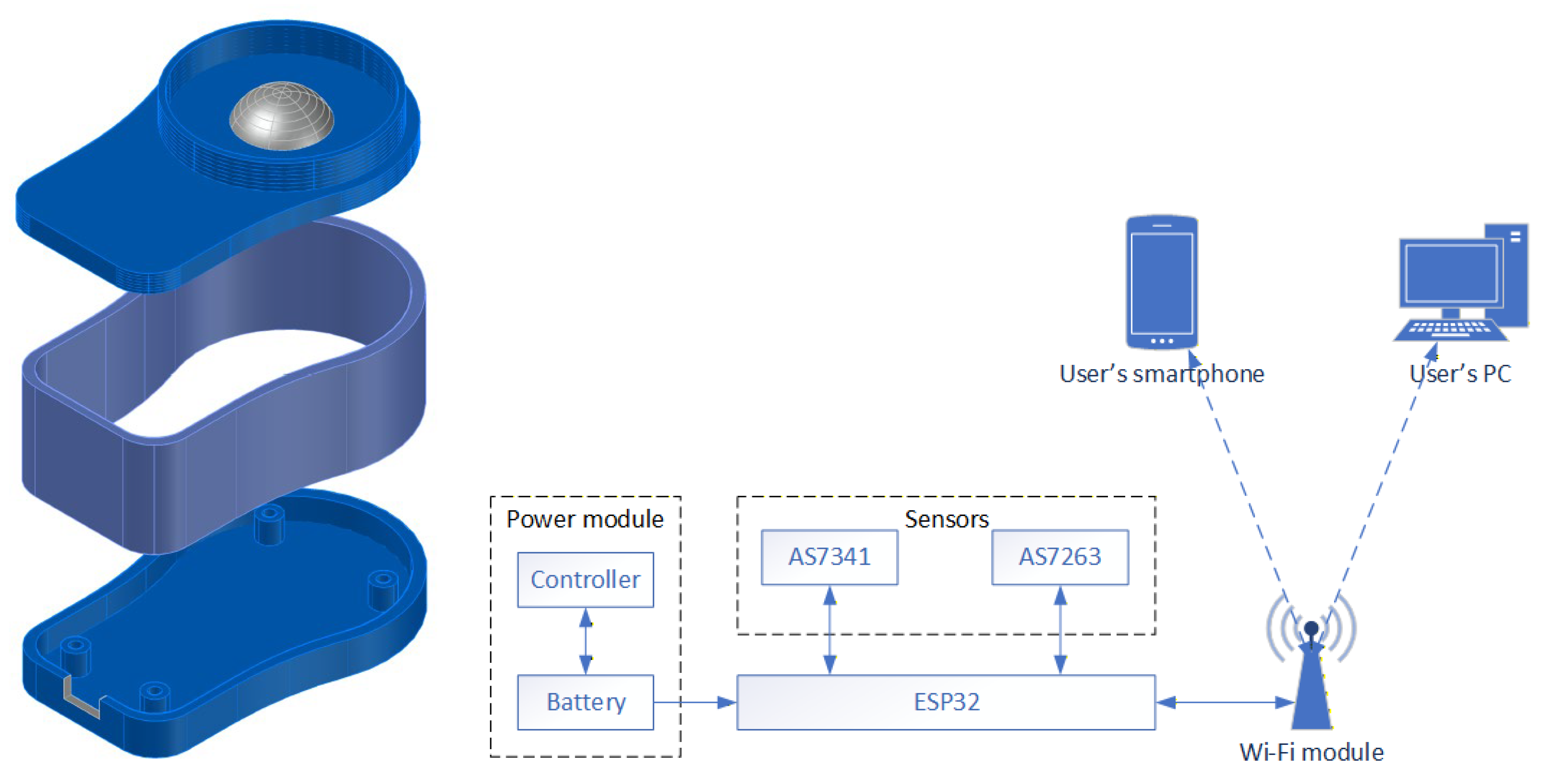

By combining several sensors in a single device, it is possible to cover the entire range of light needed to assess the plant growing environment, from blue to near-infrared radiation. As a controller for processing and transmitting information from photosensors to a mobile device, we used a module based on a low-power microprocessor, the ESP32, from the Chinese company Espressif Systems [

17]. This controller has a Tensilica Xtensa LX6 dual-core (or single-core) 32-bit processor, 520 KB of SRAM, wireless connectivity (Wi-Fi and Bluetooth v4.2), and peripheral interfaces. The controller is powered by a standard 5 V supply, allowing the use of inexpensive batteries and a USB charger. Since the ESP32 board does not support simultaneous operation with two sensors and the Wi-Fi module, the sensors operate in multiplexer mode: they are turned on alternately and each one takes measurements. The integration time for both sensors was set to 100 ms.

We placed the sensors, controller, and battery in a small 3D-printed plastic housing (

Figure 2). A hemisphere of opal plastic was installed in front of the sensors; this, combined with the geometry of the housing, provides the required cosine correction. The cosine corrector is designed so that no flux can reach the sensor at an angle of incidence of 90° or more [

18].

The following light sources were used to test the algorithm performance: LED lamps with various combinations of white, blue, green, red, and far-red SMD 2835 LEDs manufactured by Shenzhen Refond Optoelectronics Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China); sunlight in clear and cloudy weather; 400 W SYLVANIA Grolux HPS lamps (Feilo Sylvania Europe Limited, Newhaven, UK)

To calibrate the photosensors, a series of sequential measurements of light signals with a bandwidth of up to 30 nm and a peak emission wavelength from 400 to 900 nm were carried out. The light signal was generated by a halogen lamp with the spectrum close to the spectrum of a black body at a temperature of 3050 K; the band signal was extracted from the spectrum of the halogen lamp using a MUM-01 monochromator (Azov Optical and Mechanical Plant, Azov, Rostov region, Russian Federation), in which it was fixedly mounted. Measurement data were recorded using the instrument under study and a PG200N spectrometer (UPRTek Corp., Miaoli County, Taiwan) with an operating range of 350 to 800 nm as a reference instrument, both attached to eyepieces of the monochromator. Reference measurements of photon flux density, irradiance, and spectral composition of the irradiance were also performed using the PG200N. The accuracy of the PG200N spectrometer is ±5%, with the repeatability of 0.2% (data provided by the manufacturer). To ensure repeatability of the result, each measurement with the PG200N spectrometer was carried out as the arithmetic mean of three consecutive measurements.

2.2. Analysis of the Problem and Ways to Solve It

To develop the algorithm for spectral signal processing, it is necessary to solve the problem of unknown light source spectrum recovery over the entire responsivity range of the device based on the readings of the photosensors. This is an inverse problem where spectral reconstruction from multi-channel data is underdetermined, so, in general, it does not have a unique solution: as can be seen from the responsivity graphs in

Figure 1, some wavelengths are in the range between the responsivity peaks of the photosensors, so if the peak radiation intensity occurs at such wavelengths, the sensor readings will be significantly underestimated but indistinguishable from the readings for radiation lacking this peak but with the same intensity in other parts of the spectrum. Therefore, in addition to attempts to recover the spectrum, leading to ambiguous results, it is necessary to develop an algorithm that can calculate the photon flux density in the blue, green, red and far-red ranges based on the readings of the corresponding photosensors. A possible solution algorithm and its accuracy are analyzed below.

It should be noted that a number of radiation spectra have features that can lead to significant distortion of the instrument readings and make the spectrum recovery difficult. These spectra are the ones that have a wide intensity band in the invisible (near and short-wave infrared) range: the spectrum of the Sun in clear and cloudy weather, the spectrum of an incandescent lamp, and so on. The broad intensity band in the infrared range, which exceeds the intensity in the visible part of the spectrum, is because these spectra are the radiation spectra of heated bodies, and according to Planck’s law, their radiation includes the blackbody spectrum. The presence of a wide range in the near and short-wave infrared parts of these spectra with an intensity much higher than the intensity in the visible parts of the spectrum (especially in blue) leads to the fact that, although the responsivity of sensors with peaks in the visible (especially blue and green) ranges is very low at each wavelength in the infrared range, this is compensated by the larger range size and much higher radiation intensity (for example, for an incandescent lamp, the intensity at wavelengths of 400 and 1100 nm can differ by two orders of magnitude). Thus, the intensive infrared part of the spectrum can introduce noise into the sensor readings, significantly overestimating them.

Theoretically, this problem can be solved by calibrating sensors not only in the visible but also in the infrared range. In practice, this is extremely difficult not only because of the need to use special measuring equipment and monochromators to work with this spectral range, but also because, due to extremely low responsivity of the sensors in this range, the matrix of the system of linear equations will be ill-conditioned, and the measurements will have an unacceptable signal-to-noise ratio, so this calibration will be very imprecise.

In practice, there are two light sources with such properties in plant growing: sunlight and sodium lamp light. For the Sun, the source of radiation is its photosphere with a temperature of 5800 K, but the sunlight spectrum of the visible on the ground sunlight differs significantly from the spectrum of the photosphere of the Sun due to absorption of sunlight by the Earth’s atmosphere, clouds, and so on. The emission spectrum of a sodium lamp consists of intensity peaks of sodium and other elements used in the gas in the lamp tube (most often mercury), but since the operation of a sodium lamp requires heating the vapor to temperature of 1800 K [

19], then the spectrum of a black body of the corresponding temperature is added to intensity peaks of sodium and mercury. Therefore, before proceeding to calculate PFD values from the readings of photosensors, it is necessary to develop an algorithm that reliably identifies the above-mentioned anomalous light sources with strong infrared radiation based on the readings of the device, and for each type of light source, a separate PFD calculation should be made, taking into account the characteristics of this light source.

To improve measurement accuracy, it is also necessary to know the correct responsivity values for each sensor at different wavelengths. The manufacturer does not provide responsivity tables for the sensors, limiting itself to the graphs shown in

Figure 1. The simplest solution is to create a responsivity table based on these graphs, but the disadvantage of this approach is the low accuracy of the data obtained, and, in addition, the above graphs do not allow the sensor readings to be converted into mW m

−2, which will require additional calibration. Moreover, during numerous preliminary measurements, discrepancies were found between the actual readings of the photosensors and the readings that could be expected given the responsivity declared by the manufacturer. This raises doubts about the accuracy of the responsivity data provided by manufacturer and stated peak responsivity values. The solution is to calibrate the sensors using specialized equipment.

Thus, to solve the problem, it is necessary to perform the following steps.

Calibrate the responsivity of the photosensors.

Conduct a series of measurements of various light sources, namely LED lamps of various types used in plant growing, sodium lamps and sunlight in clear and cloudy weather.

Based on the data obtained during measurements and using machine learning or other methods, develop an effective algorithm that allows the type of light source (LED lamp, sodium lamp, or sunlight) to be determined based on the readings of the device.

For each light source, using machine learning methods, derive formulae that allow the PFD to be calculated based on the instrument readings in the blue, green, red, and far-red ranges.

2.3. Calibration of the Photosensors’ Responsivity

Since the PG200N reference spectrometer has a measurement range from 350 to 800 nm, the near-infrared values were calculated using Planck’s formula for a given blackbody temperature and/or using reference data on the solar spectrum [

20], the emission spectrum of the elements [

21].

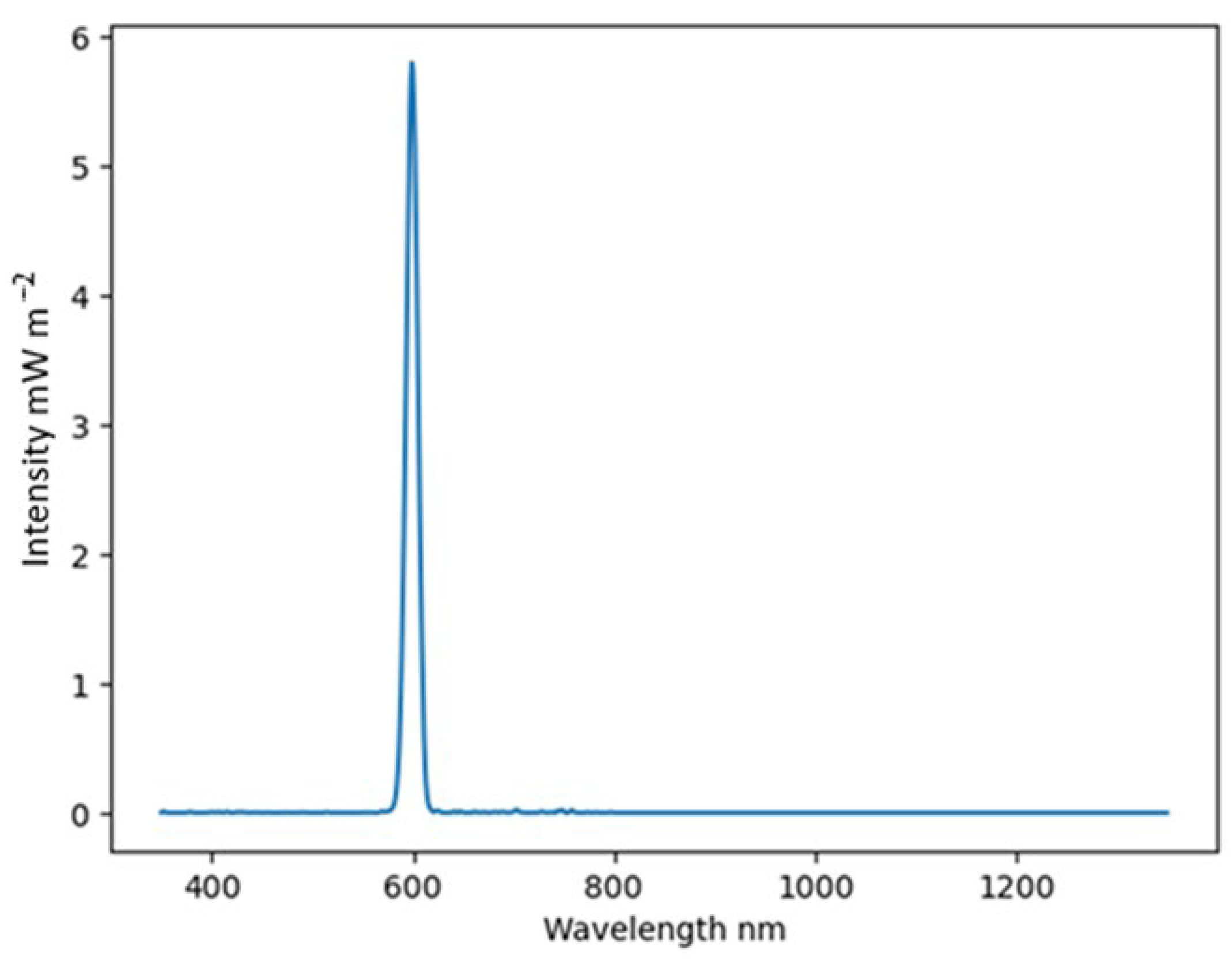

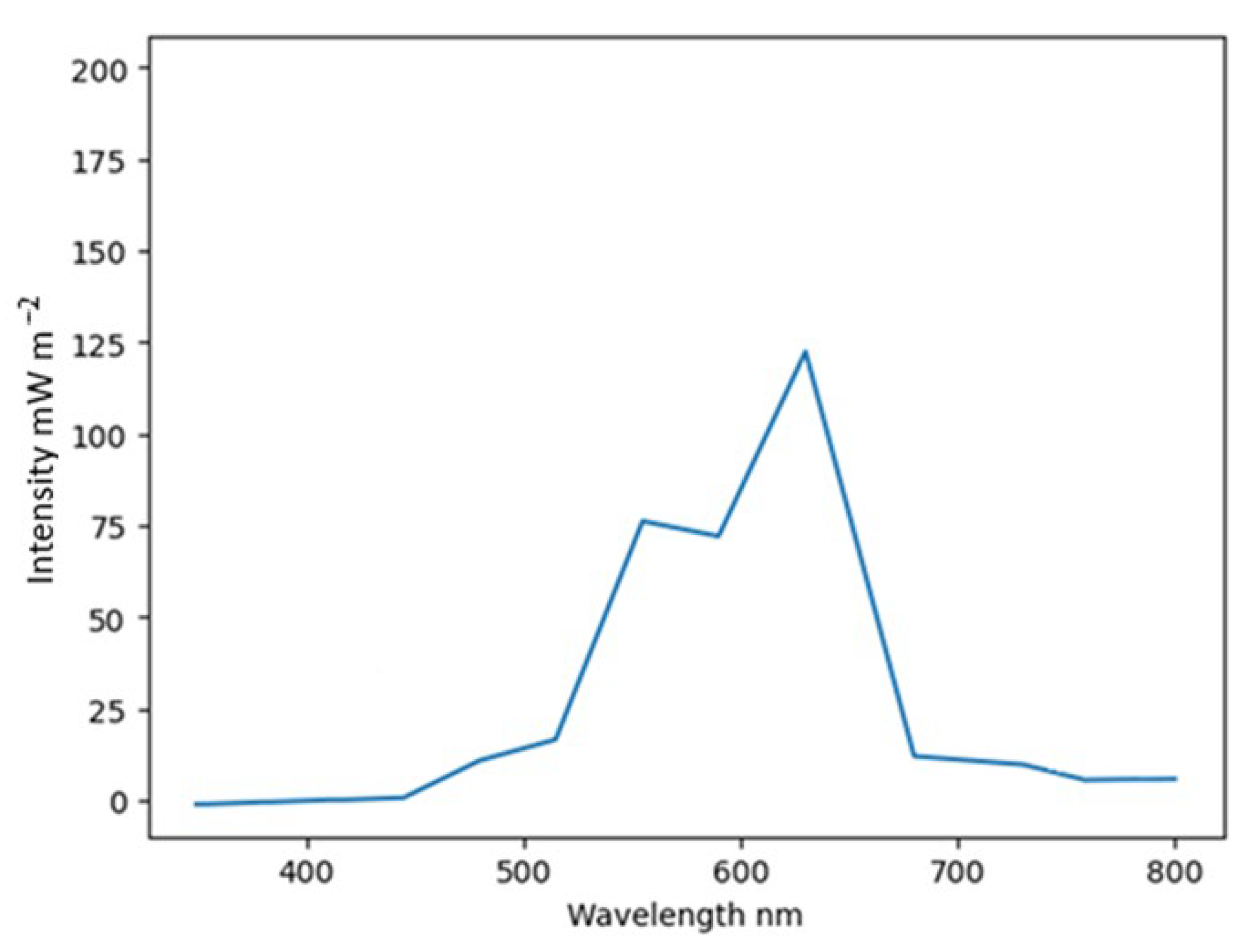

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show an example of the spectrum at the output of the monochromator and a typical graph of the light generated by the monochromator.

The readings of each sensor are directly proportional to the integral of the light intensity multiplied by the responsivity of the sensor:

where

are the sensor readings,

is the intensity at the wavelength

(measured by reference device, in mW m

−2),

is the sensor responsivity at the wavelength

.

For practical calculations, we should choose a step

and replace the integral with a sum:

where

is the

th wavelength,

is the sensor responsivity at the wavelength

.

Since is known to us from the readings of the sensor under study, and is known from the readings of the reference spectrometer, (2) is a system of linear equations with as its variables.

The choice of the measurement step is determined by several considerations. On the one hand, the measurement step should not be too big so that the sensor responsivity is approximately the same over the range corresponding to the step width, i.e., if . On the other hand, the step should not be too small: firstly, when working with the MUM-01 monochromator, the peak value error could be 1–2 nm, and secondly, measuring light signals that are too close to each other will lead to the matrix of the system of Equation (2) being ill-conditioned, and the solutions will be significantly distorted due to minor measurement errors. Based on these considerations, the measurement step nm was chosen.

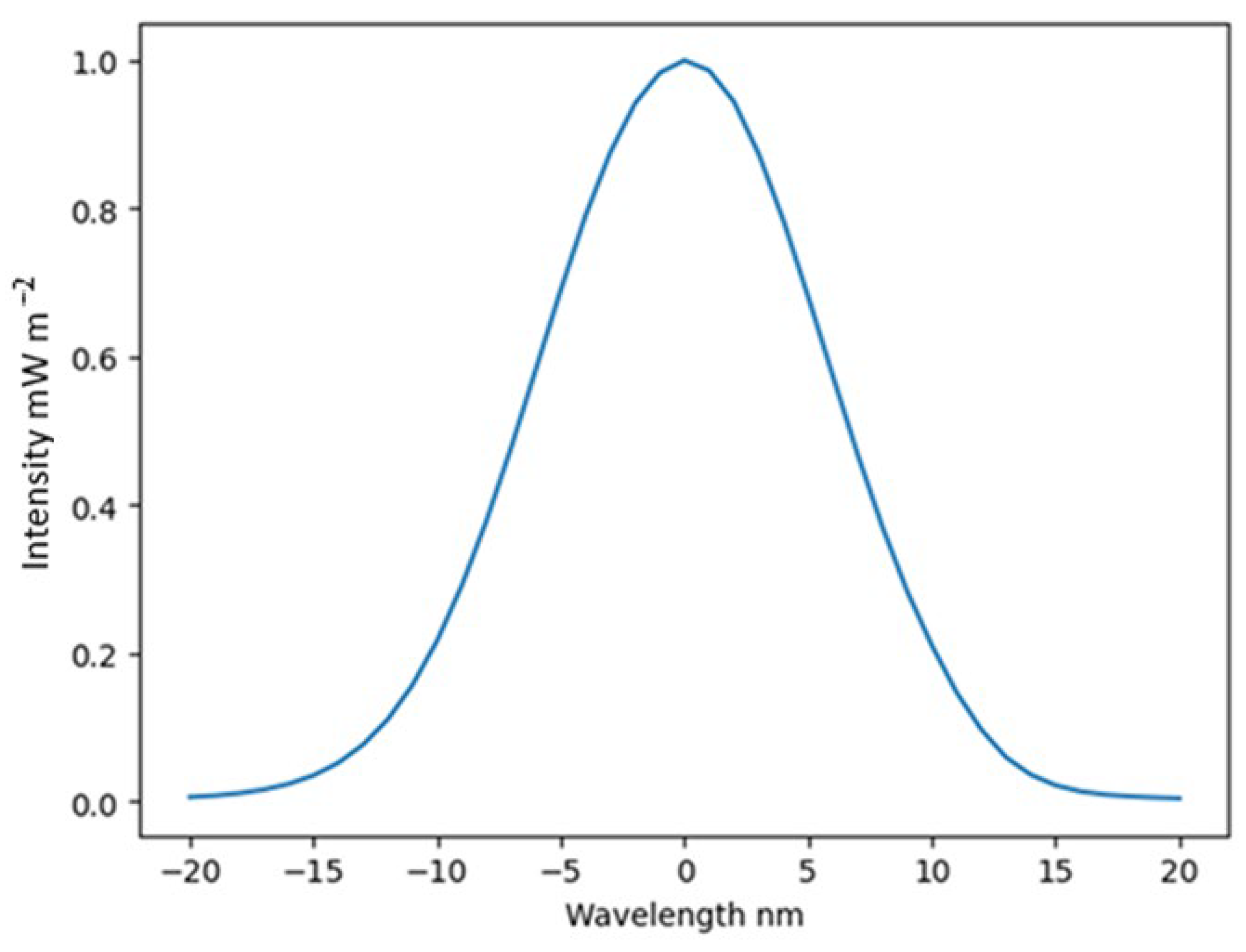

As can be seen from the graph in

Figure 4, the light signal generated by the monochromator has negligible intensity already at a distance of

from the peak. Thus, the system of Equation (2) effectively becomes tridiagonal: for each wavelength

the signals with peaks

,

,

and only these have nonzero intensity at that wavelength.

It should be noted that for

nm, it was not possible to measure

directly since these wavelengths lie outside the working range of the PG200N spectrometer. However, due to the fact that the spectrum of the incandescent tungsten filament is very close to the blackbody spectrum (which was confirmed by measurements with a spectrometer), the peak intensity values at these wavelengths were recovered using the value at the wavelength of 800 nm (3) according to Planck’s Formula (4):

where

is the radiation intensity of a black body of temperature

at wavelength

,

is the speed of light,

is the Planck’s constant,

is the Boltzmann constant. The spectrum around the peak value at all wavelengths has a form corresponding to the graph in

Figure 4.

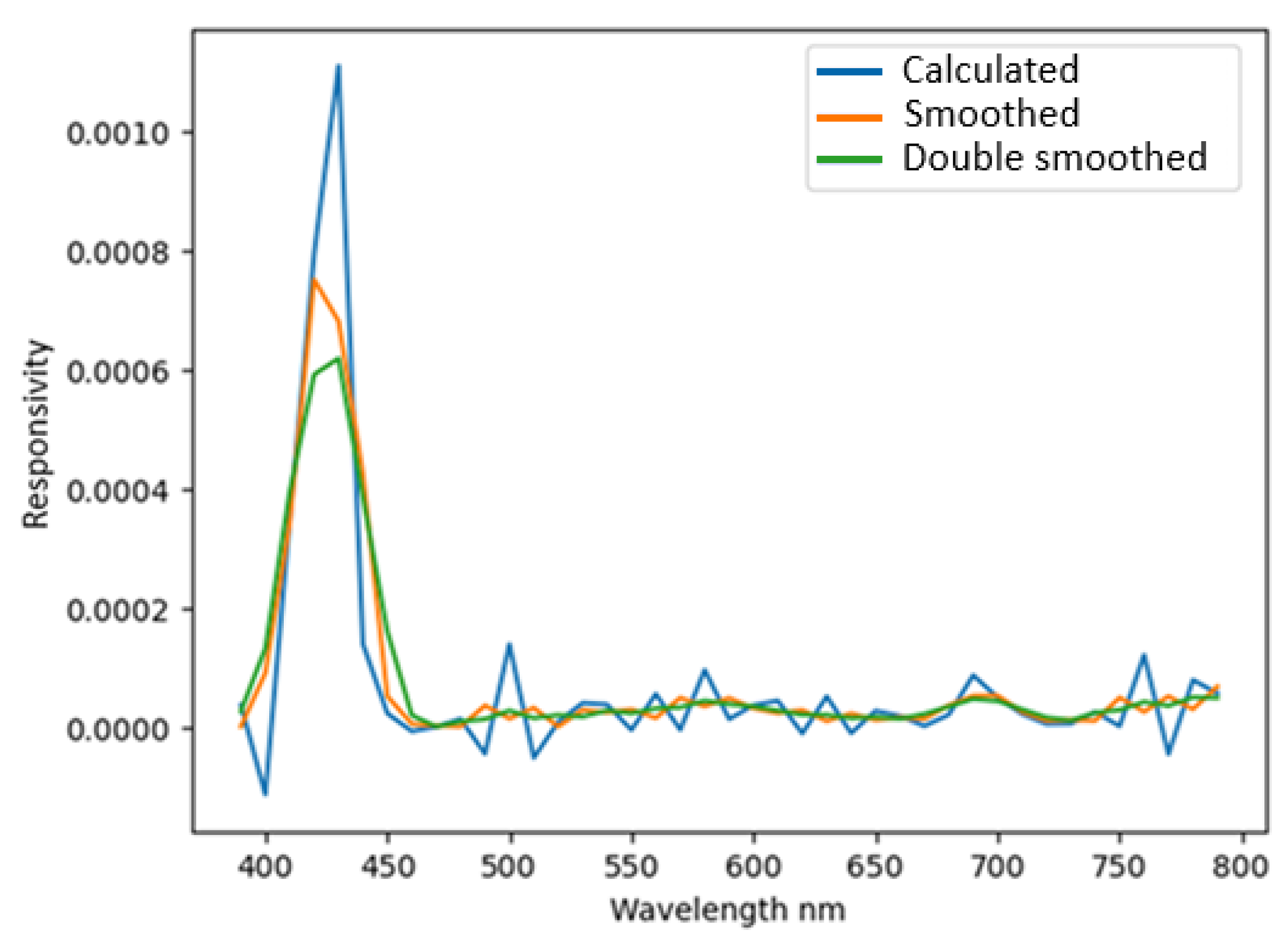

The solution of the system of linear Equation (2) gave values of the responsivity of the sensors in the range from 400 to 890 nm, example in

Figure 5.

Due to the partial overlap of the spectral channels generated by the monochromator and the presence of noise and measurement errors, the calculated responsivity plot (

Figure 5, blue curve) is distorted. Therefore, smoothed plots (orange and green curves for simple and double smoothing) were used, as they are more similar to those specified by the manufacturer; in addition, smoothing reduces the negative impact of individual measurement errors and noise.

Although the actual responsivity of the sensors was close to that declared by the manufacturer, there were also significant differences (

Table 2). For example, for most sensors, the peak of the actual responsivity was shifted to the right relative to the declared value. This explained the underestimation of LED emission readings with intensity peaks corresponding to the responsivity peaks stated by the manufacturer. Furthermore, responsivity values calculated using this algorithm allow immediate measurement of intensity in mW m

−2.

It should be noted that these measurements do not allow us to clarify the responsivity of the spectral channel with the declared peak at 910 nm. Calibration for this channel was considered inappropriate due to its very wide responsivity band, which, as will be shown below, makes the matrix of the system of linear equations ill-conditioned and the results of the work not only non-specific to a particular wavelength but also significantly distorted by measurement errors when recovering the spectrum.

2.4. Spectrum Recovery According to the Instrument Readings

With each measurement, both devices provide numerical readings, and the goal is to recover the spectrum as accurately as possible from these readings. Since the original light spectrum can be anything, certain assumptions should be made when recovering it from a limited number of parameters. Thus, for the sensors used, the spectrum of two LEDs will be fundamentally indistinguishable if one of them has a narrow peak, for example, at the wavelength of 690 nm, and the other has a wider but lower peak at the same wavelength.

Thus, the main task is to recover the function from the set of readings from 14 spectral channels. Due to the above-mentioned ambiguity of the solution, it was replaced by a simpler one: it is only necessary to recover the values of radiation intensity for the wavelengths corresponding to the responsivity peaks of individual spectral channels, and in the ranges between them the spectrum of light radiation is considered linear; moreover, outside the responsivity areas of all channels, the radiation intensity can be considered zero in most cases, since it does not affect the readings of any of the sensors. So, the recovered radiation spectrum will have a similar appearance:

The algorithm is as follows. Formula (2) is a linear relationship between the intensity perceived by each spectral channel and the intensities of the original light flux at different wavelengths. Considering the original spectrum to be piecewise linear, as in

Figure 6, we find that the entire spectrum is determined by its intensities at wavelengths corresponding to the responsivity peaks of the spectral channels, i.e., the number of variables coincides with the number of sensors, which means that we are solving a system of linear equations with the same number of equations and variables. Its solution will be the desired spectrum.

When forming a system of linear equations, it should be taken into account that the responsivity range of each spectral channel significantly overlaps the responsivity ranges of two adjacent channels, i.e., for example, the light intensity at a wavelength of 620 nm makes a significant contribution to the readings of channels with peaks at 600 nm and 640 nm; however, spectral channels with more distant peaks already have almost non-overlapping responsivity ranges, which was also verified in another study using a monochromator [

22]. It follows that for each wavelength, we only need to consider the effect of light intensity at that wavelength on the two sensors closest to it, which greatly simplifies the calculations.

Consider

sensors with responsivity peaks at wavelengths of

. Let the intensity of the luminous flux at these wavelengths be

, i.e.,

. For each

th sensor, the luminous flux

intensity actually measured by it is denoted as

. Let also

be the minimum wavelength at which at least one of the sensors has non-zero responsivity, and

be the maximum wavelength at which at least one of the sensors has non-zero responsivity. Then, as was mentioned above, we assume

. Let us rewrite Formula (2) for our case:

where

can vary from

to

.

Let us express

through

. To do this, let us remember that our spectrum is piecewise linear. If

, then, obviously,

. Then, since, as noted earlier, the readings of the

th sensor are actually affected only by wavelengths between

and

, we can write:

If we add similar terms, we obtain a system of linear equations

This is a system of equations with a tridiagonal matrix, and it can be solved, for example, by the Thomas algorithm. We will write the solution to the system as

where the matrix composed of the coefficients

will be the inverse of the matrix of the system of Equation (8).

Before applying this algorithm in practice, one very important point should be noted. The closer

and

are to each other and the more the responsivity plots overlap (as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), the closer to each other will be the values of

and

and, consequently, the closer to each other will be the coefficients in this system of linear equations. This will result in the matrix of the system of Equation (8) being ill-conditioned and even small errors in measurements or in responsivity values leading to very significant changes in the results. The solution in this case is to exclude from the algorithm those sensors whose responsivity ranges overlap most strongly with the responsivity ranges of neighboring sensors. Thus, the responsivity range of the AS7263 sensor with a peak at 620 nm significantly overlaps the responsivity ranges of the AS7341 sensors with peaks at 600 nm and 640 nm. Therefore, it seems appropriate to ignore the readings of the sensor with a peak at 620 nm and instead interpolate the spectrum at this wavelength using adjacent wavelengths. Next, both devices under study have a sensor with a peak at 690 nm; however, the responsivity range of both sensors overlaps significantly with neighboring sensors, and these sensors were also excluded from the work. There is also significant overlap between the AS7263 sensor with a peak at 870 nm and the AS7341 sensor with a peak at 910 nm; since the 910 nm sensor has a very wide responsivity range that overlaps with the responsivity ranges of the other sensors, the information obtained from it was considered less valuable, so its readings were not used in further calculations. Finally, obviously, the AS7341 total brightness and flicker channels completely overlap with all spectral channels, and their readings should also be ignored. Thus, for further calculations, it is best to select spectral channels with responsivity peaks at wavelengths of 420, 450, 490, 530, 570, 600, 640, 740, 770, 820, 870 nm—a total of 11 sensors.

2.5. Procedure for PFD Calculation Based on Instrument Readings

As stated earlier, the main light sources in plant growing are LED lamps, sodium lamps and sunlight, and each light source type (except LEDs) has its own broadband infrared spectrum that distorts the measurement results, which means that the measurement results will be distorted in different ways and will require adjustments. Therefore, it is necessary to perform a series of measurements of various light sources; after that, a classification algorithm based on the obtained data should be developed. A standard method for solving such problems with small datasets (about 50–100 samples), which are presumably easily separable based on the intensity in certain spectral regions, is to train shallow decision trees. The data were preprocessed prior to training.

Horticultural LED lamps do not have a strong infrared spectrum band; therefore, it can be expected that the readings from the most responsive sensor in this range (with a peak responsivity of 910 nm), when normalized to the total intensity, will be significantly lower for them than for sunlight or sodium lamps.

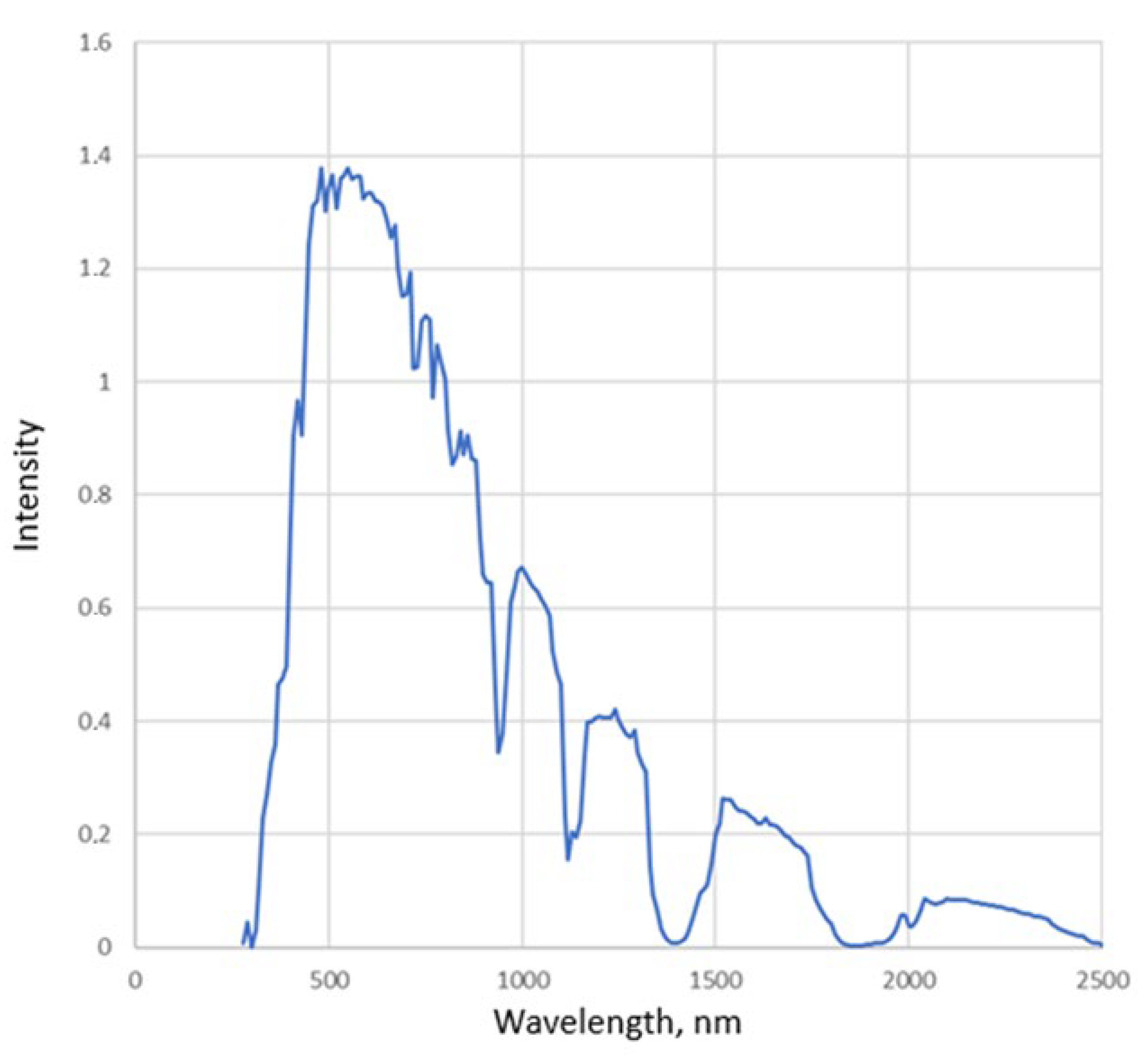

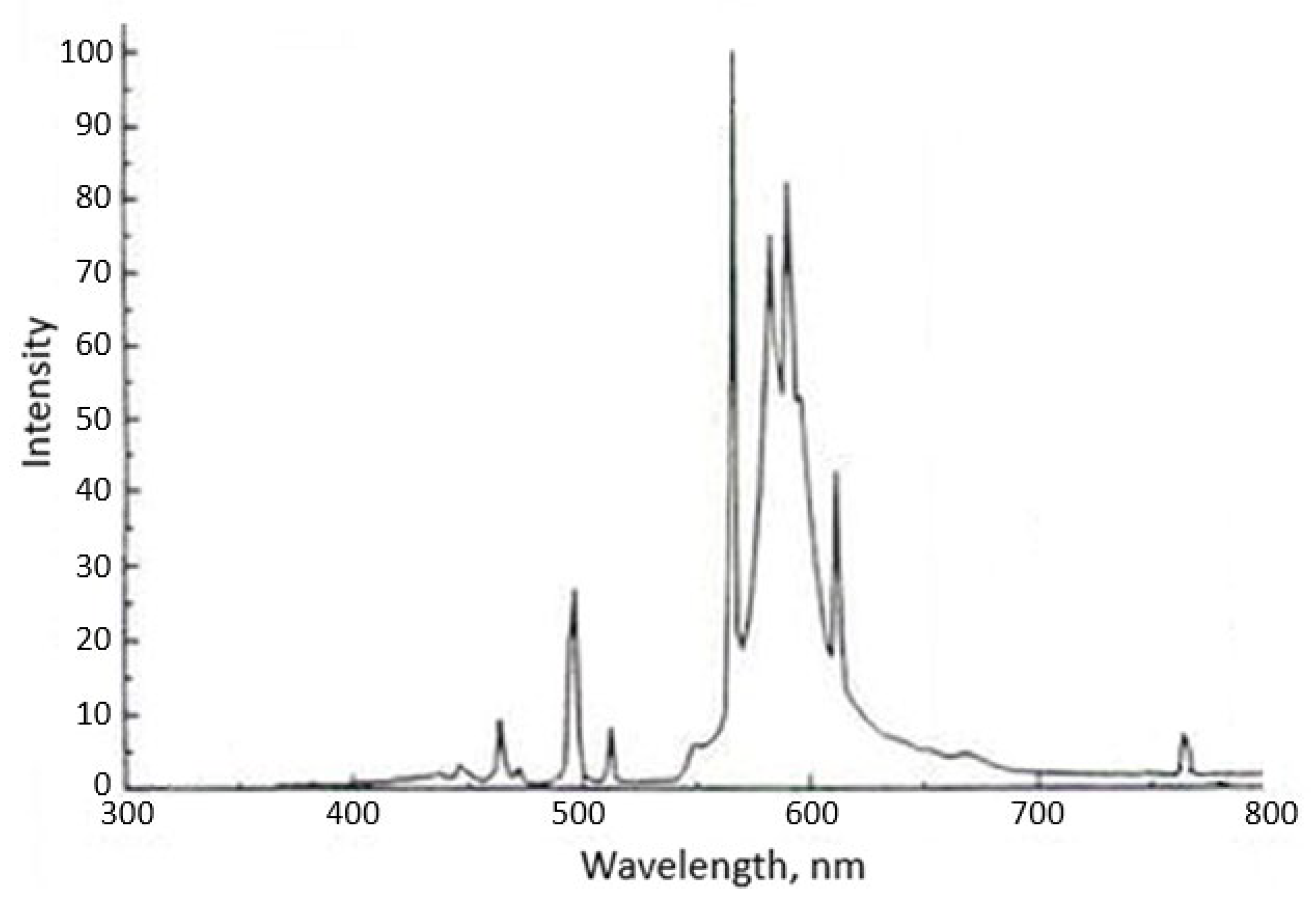

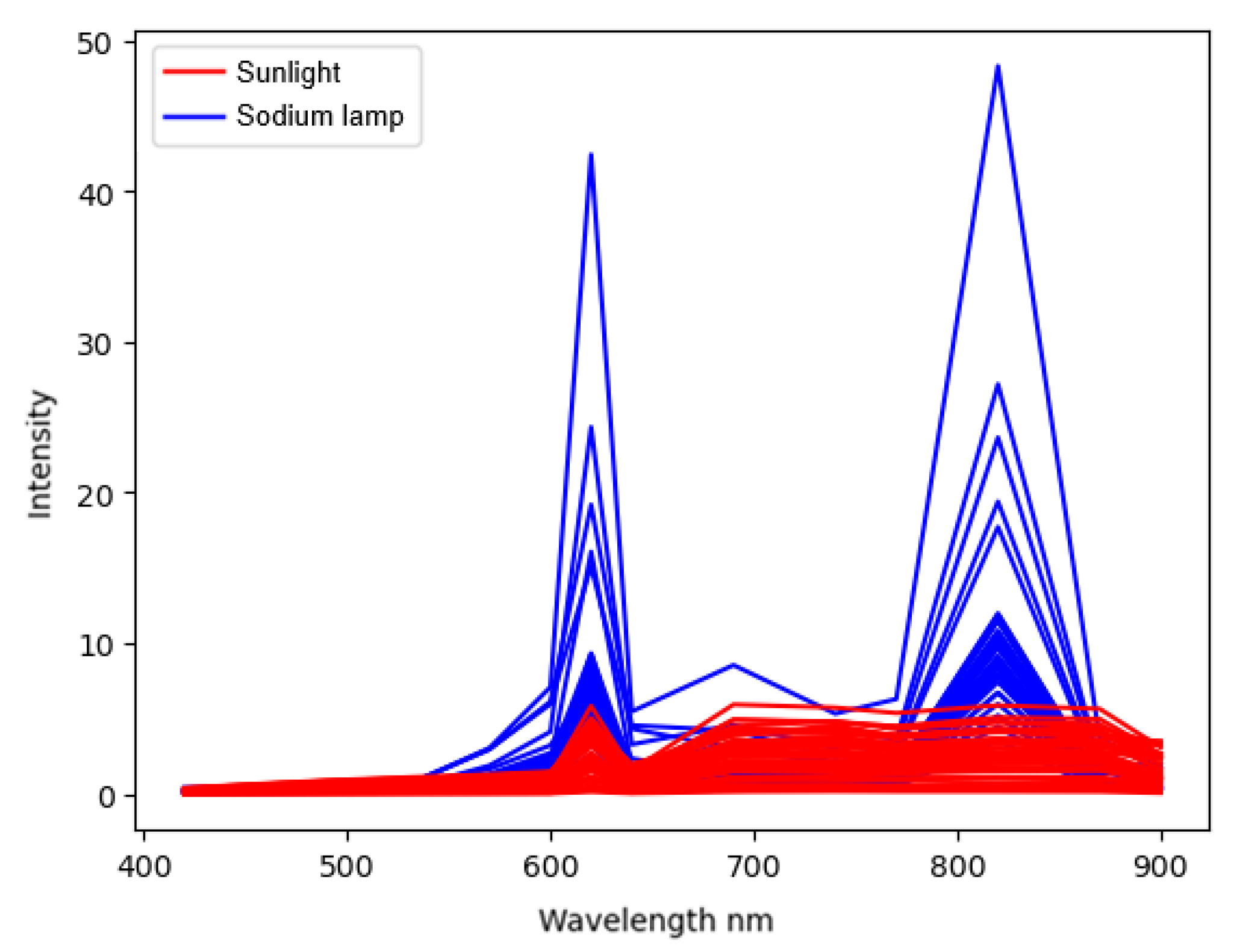

Unlike the relatively uniform solar spectrum (

Figure 7), the sodium lamp has a spectrum (

Figure 8) with very powerful peaks in the yellow-orange range (550–650 nm), a dip in the far-red range of the spectrum (700–800 nm), and a wide band in the infrared range; therefore, it can be expected that the ratio of readings from photosensors with responsivity peaks in the infrared range to readings from photosensors with responsivity peaks in the far-red range will be higher for it than for the solar spectrum.

It also seems appropriate to differentiate sunlight in clear and cloudy weather, since diffuse sunlight, in particular, reduces the proportion of the blue spectrum. It can be expected that brightness sensor readings could be used for this purpose.

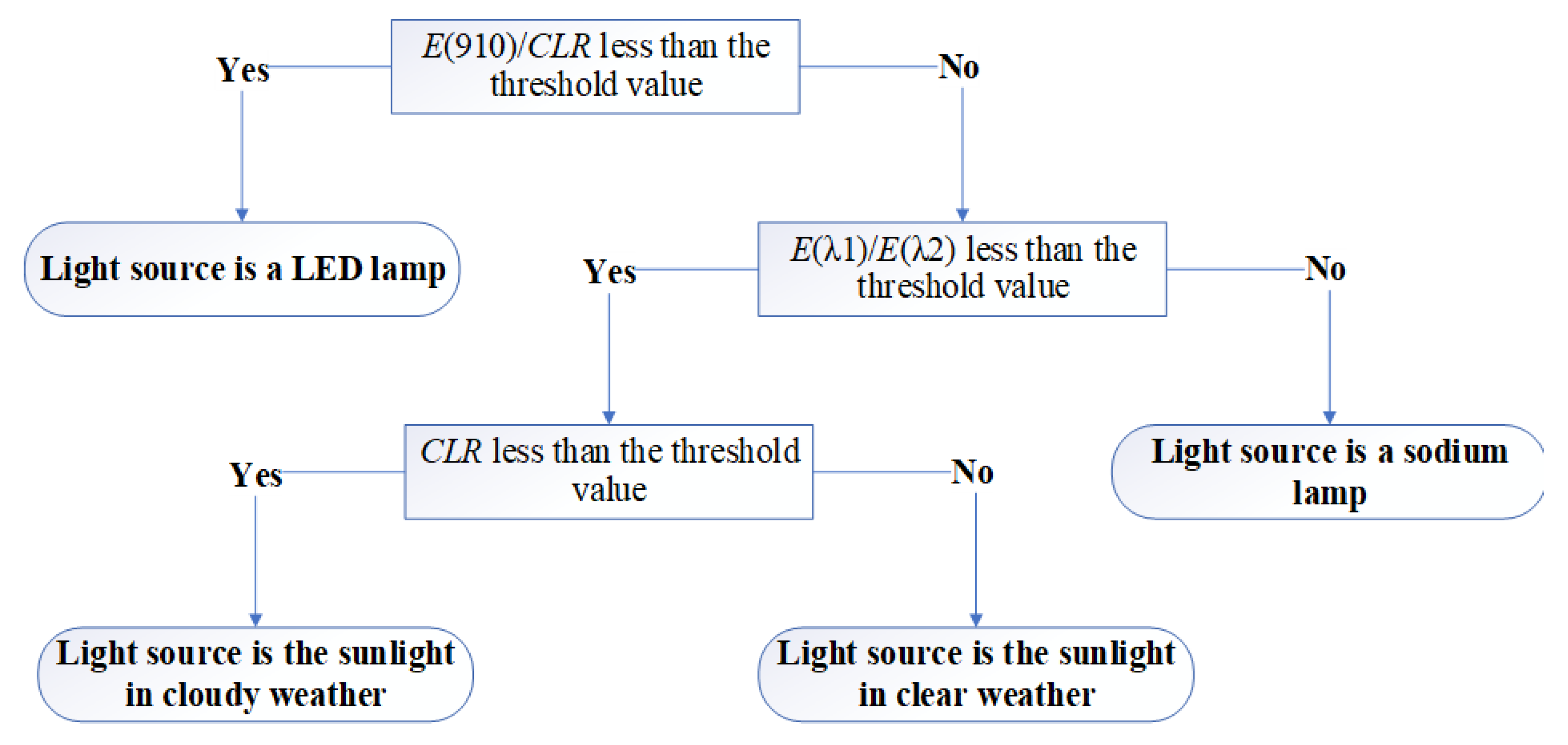

The algorithm for determining the light source type will have the form of a decision tree (

Figure 9).

For each type of light source, a series of measurements are performed using the device under study and a reference spectrometer. All PFD-B (PFD in the blue range) values are selected from the spectrometer readings, and the readings of sensors with peak responsivity in the blue range are selected from the device under study.

For LED lamps lacking a powerful bandpass spectrum, the readings from other sensors make a significantly smaller contribution and can be excluded from the calculation to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space and avoid overfitting. On the contrary, for a sodium lamp and sunlight, due to the distortions introduced by the wide-band (especially infrared) part of the spectrum, the readings of all sensors are valuable.

The resulting data set is used to train a linear regression with zero intercept (the latter is necessary to avoid overfitting by intensity readings, namely, the trained intercept will actually correlate with the average integrated light intensity in the data set, which will lead to significant errors when trying to measure a light source of a different intensity).

Similar regressions are trained for the green (PFD-G), red (PFD-R), and far-red (PFD-FR) ranges, with sensor readings with responsivity peaks in these ranges selected as features. Now, PFD values are calculated using these regressions. If the result is negative, the PFD value is set to zero. The total PPFD value is calculated as the sum of the PFD values for the blue, green, and red bands.

3. Results

The actual responsivity of the photosensors was calculated as described in

Section 2.3. Next, measurements of the spectra of the light sources specified in

Section 2.2 were made using both the device under study and the reference spectrometer. To determine the light source type, a decision tree has been trained as described in

Section 2.5 (

Figure 9). Photosensors were selected to distinguish between the solar and sodium lamp spectra; these sensors have peak responsivity at 740 and 820 nm (

Figure 10). Threshold values were also calculated.

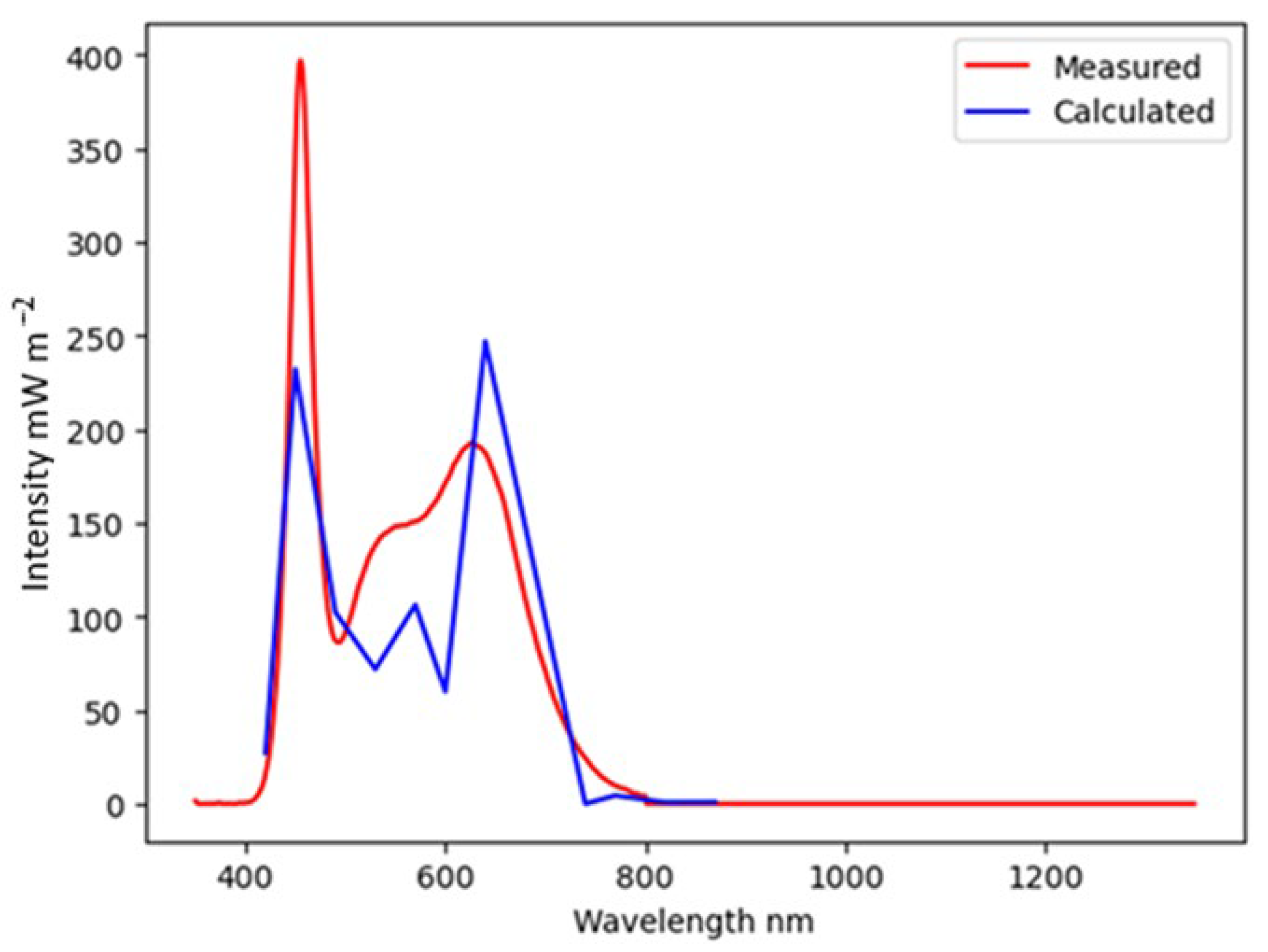

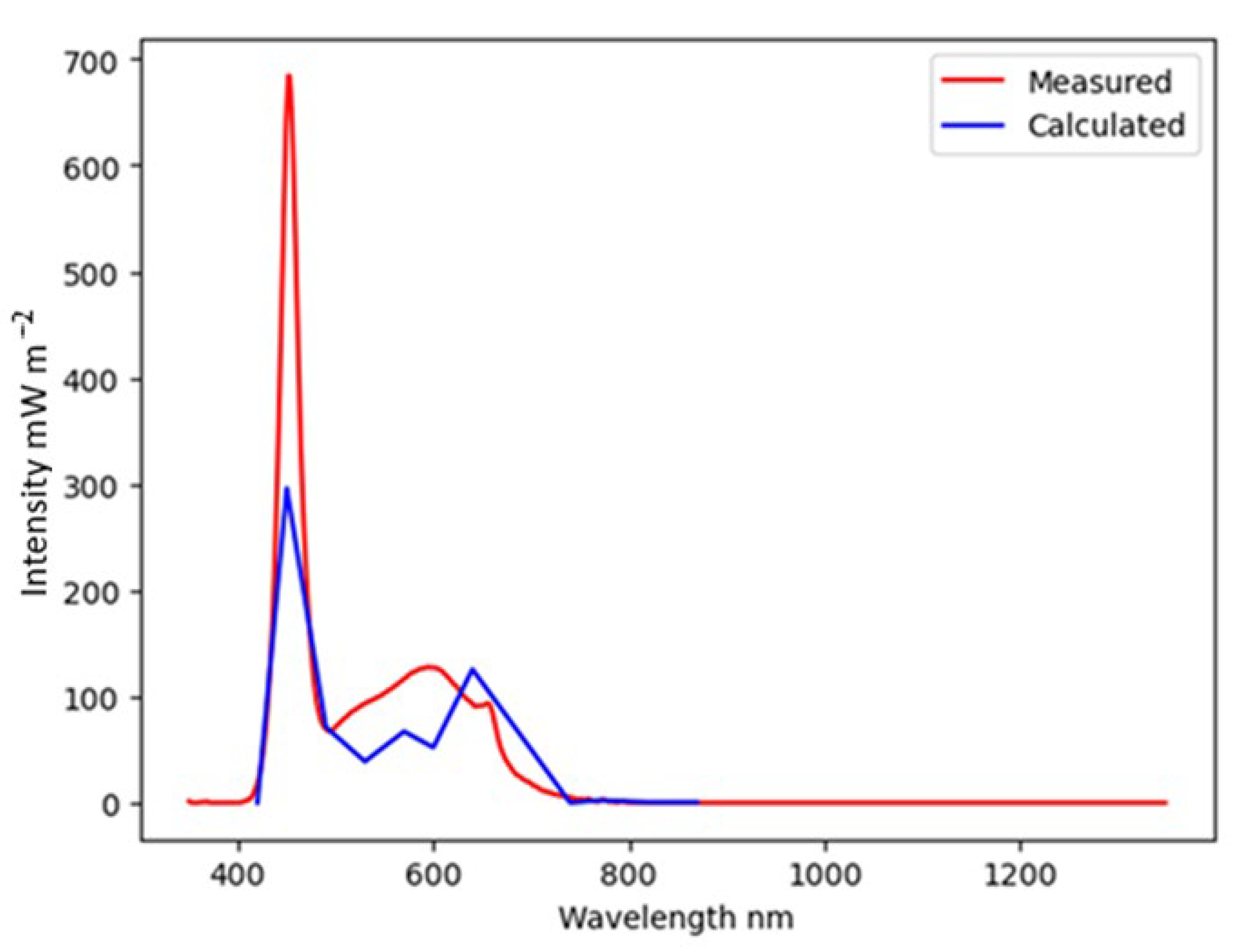

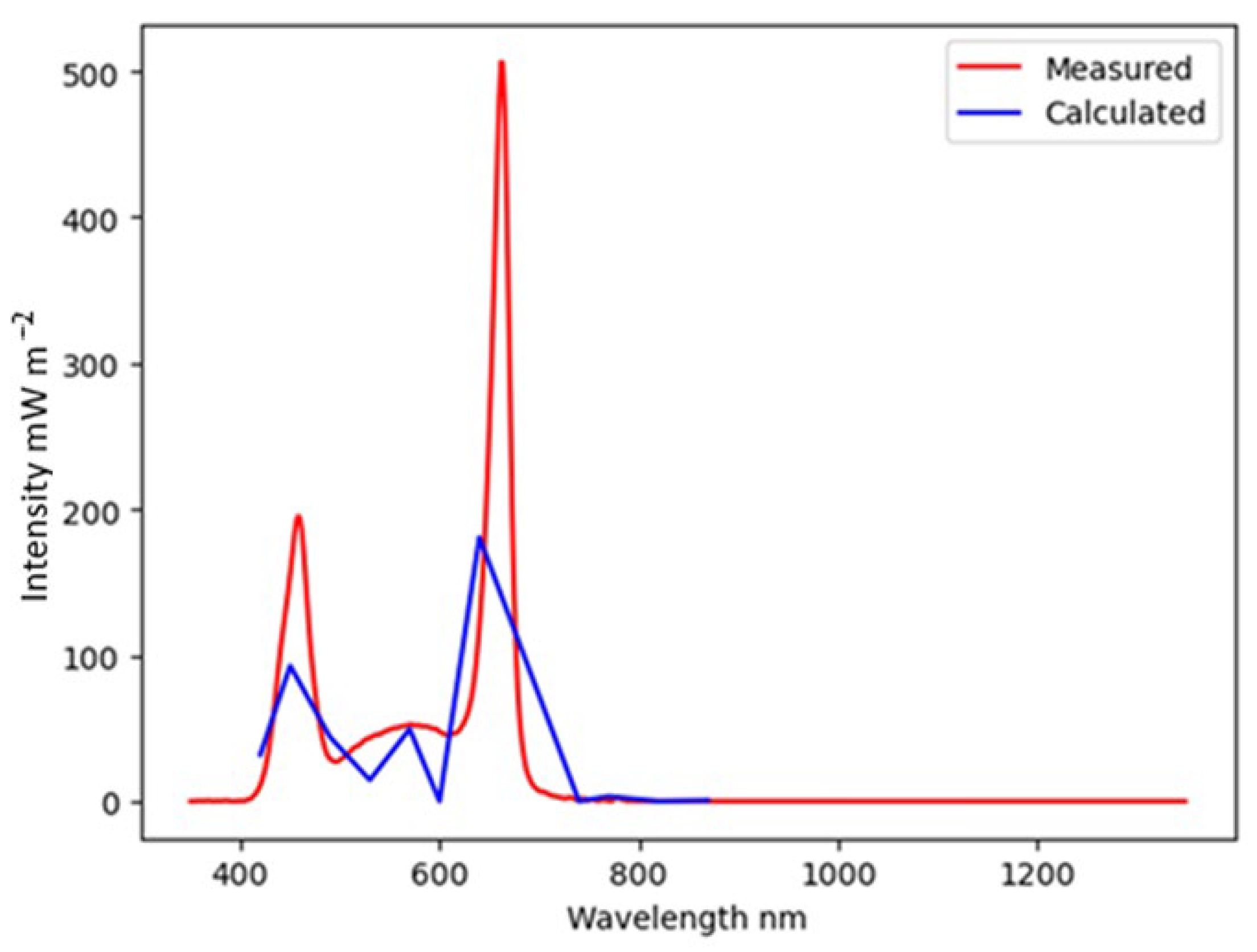

To recover the spectrum, Formula (7) was calculated, and after that, the system of linear Equation (8) was formed and solved. The resulting Formula (9) were used to calculate the recovered spectrum. Examples of the algorithm’s working results for various light sources are provided below (

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

As noted in

Section 2.2, for sunlight, a significant range of infrared radiation, not taken into account by the algorithm, leads to overestimation of instrument readings and, consequently, to distortion of the results of the algorithm. For example, when measuring the spectrum of an incandescent lamp, the readings of sensors with a peak responsivity in the blue region are overestimated several times compared to the readings when measuring the spectrum of LEDs, which have a higher intensity in the blue region. At the same time, for LED lamps, the spectrum is being recovered in an acceptable manner; however, if there are peaks between the responsivity peaks of the photodiodes, their intensity is significantly underestimated.

Next, a series of measurements of light sources of different types were carried out; for each type, a linear regression from

Section 2.5 was trained. After that, control measurements were made using the device under study and the reference spectrometer, including light sources that were not used in training the regressions and decision trees (other LED lamps, sodium lamps, sunlight light at different intensities, under different cloud cover, and at different viewing angles). A total of 77 measurements constituted the test sample.

Since precise spectrum recovery is impossible, the algorithm quality metrics were the PFD calculation error and the decision tree accuracy. For all measurements, the decision tree correctly identified the light source type. The PFD calculation accuracy is presented in

Table 3.

As can be seen, the average error in calculating the PFD for LED lamps is higher than for sodium lamps and sunlight. This is because sodium lamps have similar spectra, as does sunlight, and the regression, once trained on the training set, produces consistently good results. At the same time, LED lamps have a diverse spectrum; some lamps have peaks in the red and far-red ranges that lie outside the high-responsivity region, while others do not; in addition, a significant portion of the data in the red and far-red ranges had low intensity and, as a result, was noisy. However, it should be noted that the accuracy of the algorithm is quite high; the error in calculating the PFD in most cases does not exceed 10 µmol m−2 s−1, and for a sufficiently high radiation intensity does not exceed 10%. The high coefficient of determination shows that the algorithm correlates well with the PFD variance; the lower value for the sodium lamp spectrum in the blue region is due to the fact that the sodium lamp has a very low radiation intensity in this part of the spectrum and at the same time there is significant noise in the signal from the infrared part of the spectrum, due to which the signal-to-noise ratio is low and it is difficult to accurately recover the intensity in the blue part of the spectrum; considering that it is low and of little interest, and the accuracy of its recovery is acceptable, the performance of the algorithm can be considered satisfactory.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed an algorithm that allows for high-precision recovery of continuous spectra from readings from two low-cost matrix photodetectors, the AS7341 and AS7263. This solution can be applied to a variety of applications, such as determining color temperature or illuminance assessment.

Attempts to use the readings of such devices have been made previously. For example, an attempt was made to recover the infrared part of the spectrum from a visible color image [

24]; this problem was solved, but during its solution, image classification was used: with the help of machine learning methods, an image was assigned to one of the categories for which a clear relationship between the visible and infrared parts of the spectrum has been derived. Data from the AS7341 sensor was used to estimate the PAR [

13]; however, the spectrum was not recovered, but only the photosynthetic photon flux density was calculated instead. Using a network of such sensors, the leaf surface area was assessed; for this purpose, the illumination in the areas above and below the leaves was assessed [

25], and the sensor readings were used to obtain an illumination indicator—a task similar to that performed by a lux meter or quantum sensor.

The task of spectrum recovery using sensor readings on multiple channels is challenging, as the spectra of light sources can vary widely, including within the same responsivity ranges. However, estimating the intensity at specific ranges and constructing a piecewise linear approximation of the spectrum is possible. In a number of works, the piecewise linear spectrum obtained from the instrument readings is used for further work; for example, AS7341 readings are used to estimate the chlorophyll content in leaves [

26]. However, in such studies, a spectrum of a pre-known shape is investigated, which guarantees a high correlation of the calculated vegetation index (most often representing the ratio of intensity at different wavelengths) with the measurement results, and also eliminates the need to calculate intensity in mW m

−2.

The developed algorithm, unlike previous studies, allows not only to estimate the PFD across four spectral ranges (blue, green, red and far red) for a therefore uncertain light source with high accuracy instead of calculating the overall PPFD, but also, in many cases, to reconstruct the emission spectrum of the light source with acceptable accuracy.

The algorithm discussed in this article can be improved in further research. For example, it could classify different types of LED luminaires; calculating the photon flux density for each individual luminaire type could be more accurate. In addition, more precise handling of sunlight (for example, training the algorithm on a larger volume of data under different illumination at different times of day and determining the final result as a combination of illumination at different times of day in accordance with the readings of the brightness sensor) or working with a large number of sodium lamps of various characteristics is possible.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the concept of a low-cost portable spectrophotometer based on the AS7341 and AS7263 spectral sensors. For the first time, the problem of recovering the spectrum of a previously unknown light source was addressed. An algorithm identifying the light source type and calculating not only specific ratios and/or overall irradiance levels but also the light intensity at each responsivity range was developed. For the light sources under study (sunlight, LED and HPS lamps), the measurement error did not exceed 10%. A limitation of the research is that the algorithm was developed to assess the light environment in crop production, and when measuring light sources other than those used in crop production, the error may be higher.

The developed device can be used as a low-cost alternative to spectrometers and lux meters for measuring illumination in plant growing. The advantage of this device over previously developed inexpensive quantum sensors is the ability to measure photon flux density across four spectral ranges for more precise control over the distribution of light used by plants for growth. This will help create more balanced lighting that suits the plant’s needs. In further research, the algorithm discussed in this article can be improved for classifying different types of LED luminaires, different sunlight intensities and/or cloudiness, and other lamps, which will increase the accuracy of calculating the photon flux density of light sources other than those used in horticulture.