Ethics and Law in the Internet of Things World

Abstract

:Security must be built into the foundation of the IoT solution.Jason Porter

Trust is the backbone of IoT, and there is no shortcut to success.Giulio Coraggio

As a global community, we face questions about security, equity, and human rights in a digital age.We need greater cooperation to tackle challenges and mitigate risks.Antonio GutteresUN Secretary-General

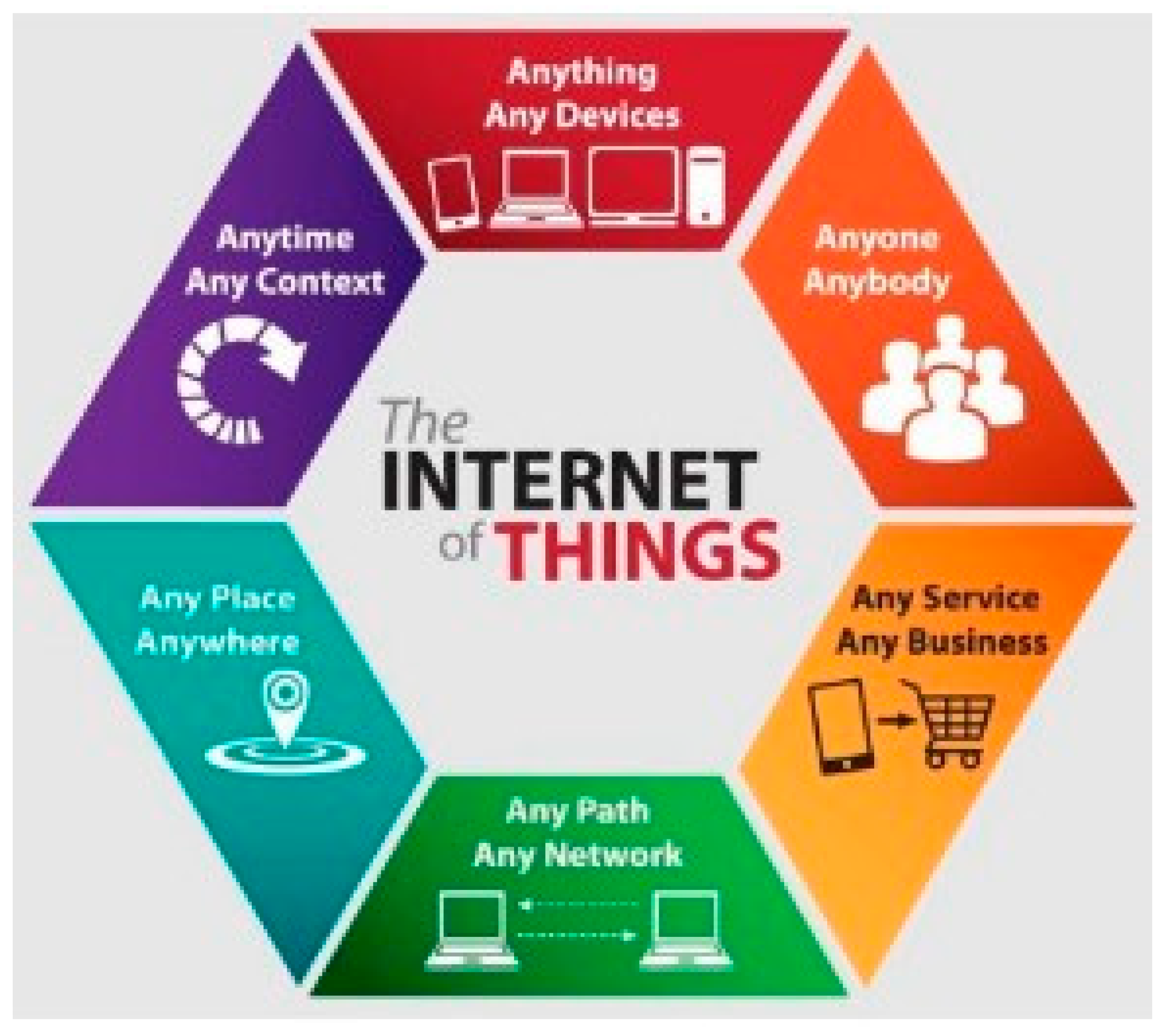

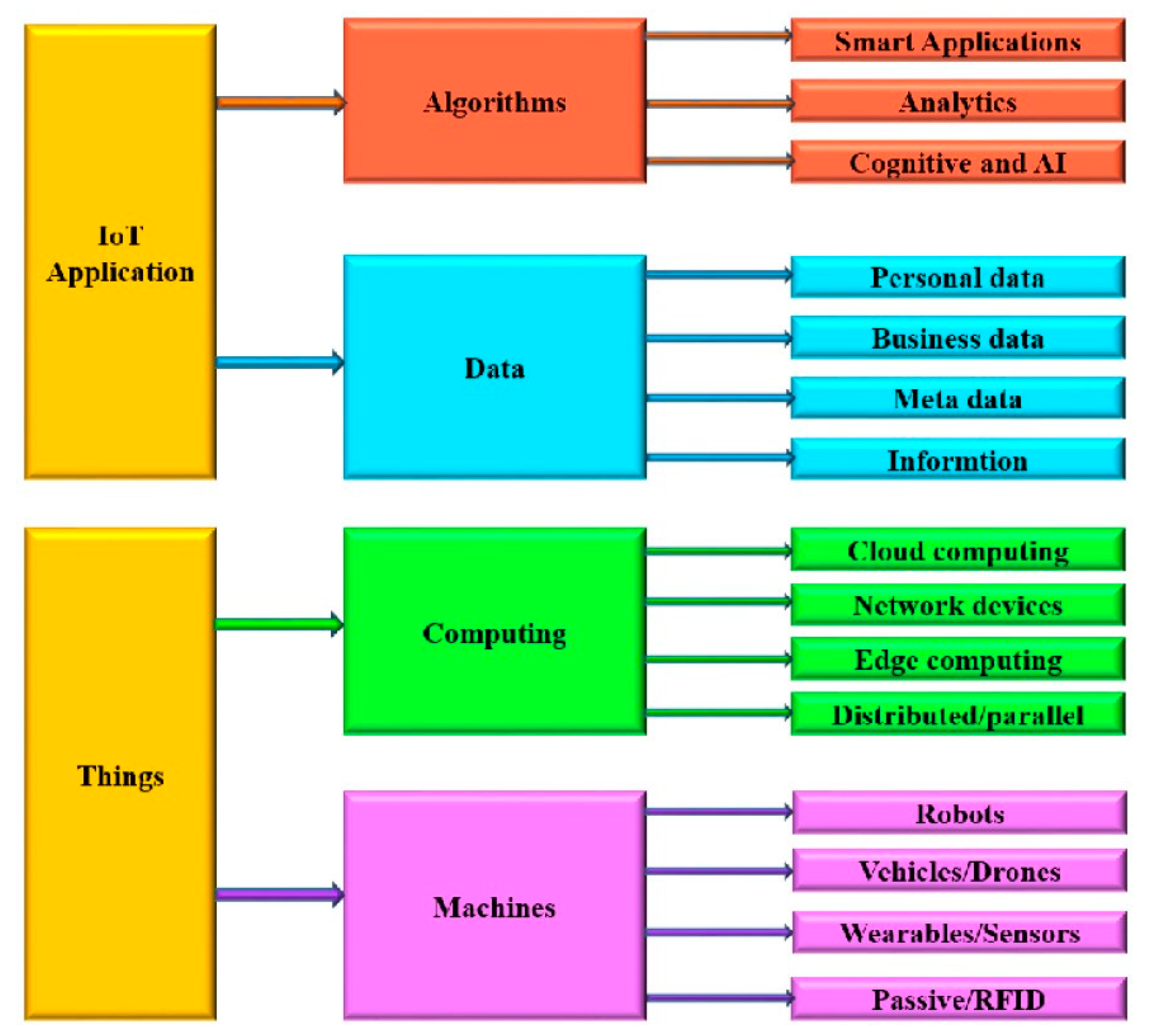

1. Introduction: What Is the Internet of Things (IoT)?

- People to people.

- People to things (objects, machines).

- Things/machines to things/machines.

- Device registration.

- Device authentication/authorization.

- Device configuration.

- Device monitoring.

- Device fault diagnosis.

- Device troubleshooting.

- Privacy and security.

- Lack of sound business structures.

- Governance structures

- Lack of interoperability.

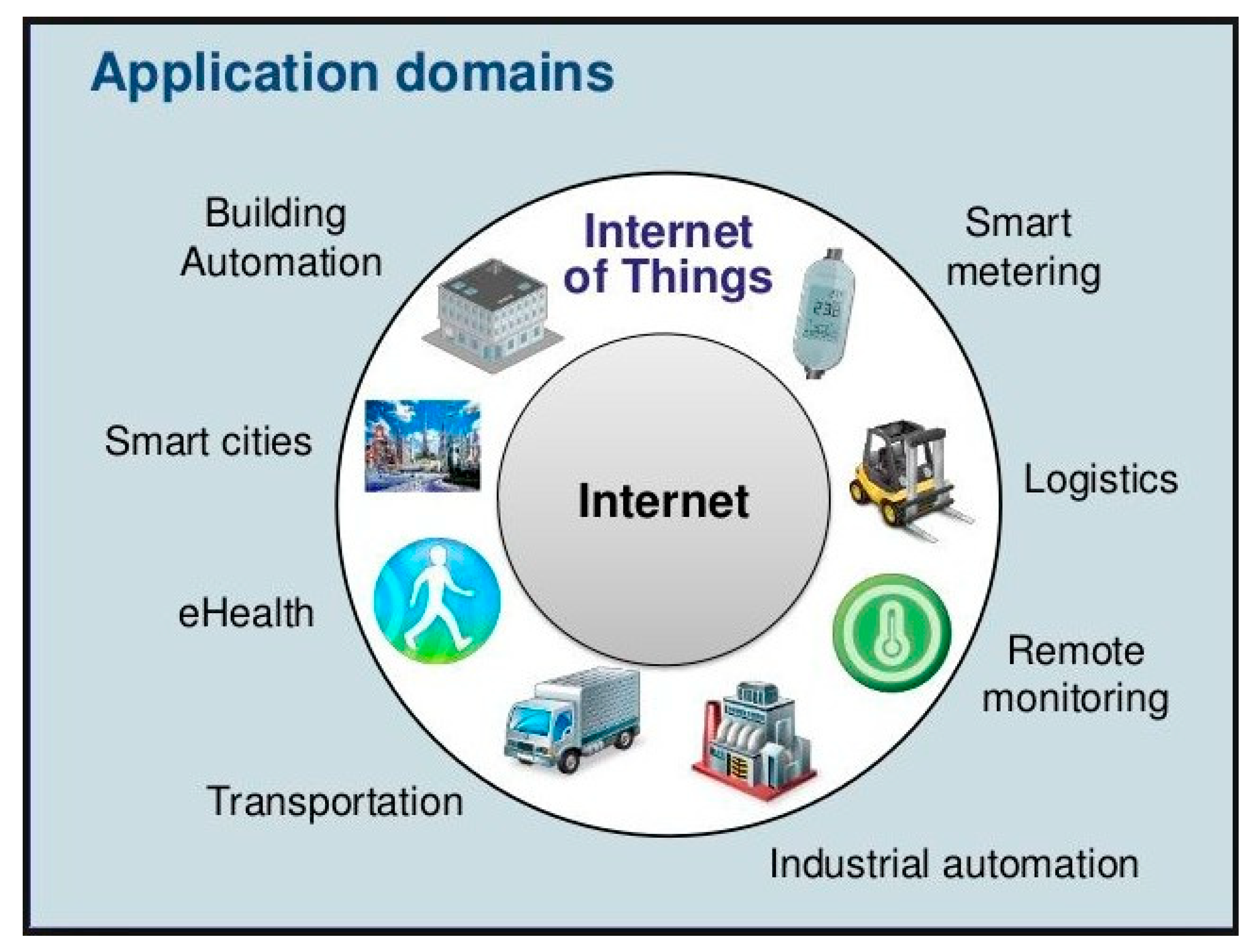

- Wearable health technologies (for example, wearable devices that continuously monitor the health status of a patient or gather real-world information about the patient such as heart rate, blood pressure, fever, etc.).

- Wearable textile technologies (for example, clothes that can change their color on demand or based on the biological condition of the wearer or according to the wearer’s emotions).

- Wearable consumer electronics (for example, wristbands, headbands, rings, smart glasses, smart watches, etc.).

- Gives a list of the key historical landmarks of IoT.

- Provides a short account of ethics (branches and methods).

- Discusses the similarities and differences of law and ethics.

- Presents fundamental general issues of IoT ethics.

- Investigates the role of governments in IoT.

- Makes a tour to the European Union (EU) and United States regulations for IoT.

- Presents the IoT characteristics that may cause ethical problems.

- Provides a list of fundamental IoT ethics questions and IoT ethics principles.

- Discusses the aspects of security, privacy, and trust in the IoT.

- Outlines the need for an ethical culture of IoT related companies, and an ethical leadership of their managers/decision makers.

2. Key Historical Landmarks of IoT

- In the 1990s Internet wave 1 billion users were connected to the Internet.

- In the 2000s mobile Internet wave another 2 billion users were connected, and this number is increasing very quickly.

- Presently, the IoT has the potential to connect to the Internet as many 50 billion “things” by 2020.

3. About Ethics

- Metaethics.

- Normative ethics.

- Applied ethics.

- Moral principles.

- Values.

- Rules and regulations.

- Rules of conduct.

- Ethical practices.

- Would I want my decision published?

3.1. Ethics Theories

- Liberty principle: each human has an equal right to the widest basic liberty compatible with the liberty of others.

- Difference principle: social and economic inequalities must be regulated so as they are reasonably expected to be to everyone’s benefit attached to positions and offices to all.

3.2. Other Theories

- The basics (things that are necessary for the survival of any society, namely protection of life and property, protection of the society against outside threats, etc.).

- Civil rights (freedom of speech, freedom of religion, etc.).

- Ethical values that specify what is right or wrong and moral or immoral (these values define what is allowed or prohibited in the society that holds them).

- Ideological values which refer to the more general or wider areas of religion, political, social, and economic morals.

4. Law versus Ethics

5. IoT Ethics: General Issues

- Protection of privacy.

- Data security.

- Data usability.

- Data user experience.

- Trust,

- Safety, etc.

6. The Role of Governments

- User role: governments plan to get smart cities all over the world and become major users of IoT. As such they set how IoT should be employed, and specify sound requirements for assuring highly secure, reliable, and robust IoT products and solutions.

- Infrastructure provider role: governments should issue regulations for devices not originally intended for connection to the IoT, as well as for devices particularly designed to be connected devices. The former class raises more crucial concerns, and the governments should release license regulations on the basis of proper security standards and compliance criteria. Governments should ensure that IoT products and solutions are used exclusively for their specified goal, otherwise there is greater risk to be compromised or to be vulnerable.

7. European Union and United States IoT Regulations

- Legislation/regulations.

- Ethics principles, rules and codes.

- Standards/guidelines.

- Contractual arrangements.

- Regulations for the devices connected.

- Regulations for the networks and their security.

- Regulations for the data associated with the devices.

7.1. European Union

- EU DPR-2012: European Data Protection Regulation: the purpose of this regulation [23] is to assure the protection of “personal data” of individuals independently of what type of processing is taking place. Personal data include any data than can be referred to individuals, which implies that the concept of individual data can extend to vast areas of IoT.

- EU Directive-2013/40: this Directive deals with “Cybercrime” (i.e., attacks against information systems). It provides definitions of criminal offences, and sets proper sanctions for attacks against information systems [24].

- EU NIS Directive-2016: this Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive concerns “Cybersecurity” issues. Its aim is to provide legal measures to assure a common overall level of cybersecurity (network/information security) in the EU, and an enhanced coordination degree among EU Members [25].

- EU Directive 2014/53: this directive is concerned with the standardization issue which is important for the joint and harmonized development of technology in the EU. Its title is: “On the harmonization of the laws of the member states relating to the marketing of radio equipment” [26].

- EU GDPR: European General Data Protection Regulation-2016: this regulation concerns privacy, ownership, and data protection and replaces EU DPR-2012. It provides a single set of rules directly applicable in the EU member states [27].

- EU Connected Communities Initiative: this initiative concerns the IoT development infrastructure, and aims to collect information from the market about existing public and private connectivity projects that seek to provide high speed broadband (more than 30 Mbps). It also attempts to identify technical assistance needs of local communities and provides targeted support to promoters of more advanced projects. The initiative brings different local communities/municipalities together in order to help them find and obtain financial support for developing business models to deliver broadband to their area [28].

- Europe 2020 “Innovation Europe” Initiative: this ambitious initiative provides a framework program for funding novel projects (IoT and other) such as the “Horizon 2020” [29]. One of the seven parts of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth is the “Innovation Union” (IU). The IU involves several actions towards achieving the following three goals:

- Make Europe one of the world-class science performers.

- Free the innovation from obstacles such as expensive patenting, market fragmentation, and skills shortages.

- Revolutionize the way public and private sectors cooperate (e.g., via innovation), and enhance partnerships between European institutions, authorities (national and regional), and business.

- Establishing a cooperation platform for IoT activities in Europe and becoming a major worldwide contact point for IoT research.

- Defining an international strategy for cooperation in the IoT field of research and innovation.

- Coordinating the cooperation activities with other similar EU clusters and projects on IoT and information and communication technology (ICT).

- Organizing workshops and debates leading to a deeper understanding of IoT, future Internet, 5G, and cloud technology.

7.2. United States

- White House Initiative 2012: the purpose of this initiative [38] is to specify a framework for protecting privacy of the consumer in a networked work. This initiative involves a report on a ‘Consumer Bill of Rights” which is based on the so-called “Fair Information Practice Principles” (FIPP). This includes two principles:

- Respect for Context Principle (consumers have a right to claim that the collection, use, and disclose of personal data by Companies are done in ways that are compatible with the context in which consumers provide the data).

- Individual Control Principle (consumers have a right to exert control over the personal data companies collect from them or how they use it).

- IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act 2017: this is a bill before the US Senate that aims to improve the security of Internet-connected devices [39]. The bill defines IoT devices as any device which is connected to and uses the Internet. The bill does not put requirements on manufacturers of such devices, but it follows another approach. That is, the bill directs government agencies to include certain clauses in their contracts that demand security features for any Internet-connected devices that will be acquired by the US government. The bill describes what these clauses are and how a waiver to these required features can be obtained, and requires that the devices to be sold rely on international standards (ISO, NIST, etc.) [40].

8. IoT Characteristics that May Cause Ethical Problems

- Ubiquity/omnipresence: the IoT is everywhere. The user is attracted to IoT, absorbed by it; there is no clear way out.

- Miniaturization/invisibility: computers and devices will be smaller and smaller, and transparent, thus avoiding any inspections, audit, quality control, and accounting procedures.

- Ambiguity: the distinction between the natural objects, artifacts, and beings will be more and more difficult to be made, because the transformation from one category to another is easy, based on tags.

- Difficult identification: objects/things have an identity in order to be connected to the IoT. The access to these objects and the management of their identities might cause crucial problems of security and control in the IoT ecological world.

- Ultra connectivity: the huge number of connections of objects and people require the transfer of large quantities of data (big data) which could be maliciously used.

- Autonomous and unpredictable behavior: the interconnected objects might interfere autonomously and spontaneously in human activities in unexpected ways for the users or designers. People, artifacts, and devices will belong to the same IoT environment, thus creating hybrid systems with unpredictable behavior. The incremental development of IoT will lead to emerging behaviors that the users could not fully understand.

- Incorporated intelligence: this will make the objects as substitutes of social life. The intelligent objects will be dynamic with an emergent behavior. Being deprived of these devices will lead to problems (e.g., teenagers without the Google, smart phone or social media, might feel themselves cognitively or socially handicapped).

- Decentralized operation: the IoT control and governance cannot be centralized, because of the large number of hubs, switches, and data. The information flows will be eased, and the data transfers will be faster and cheaper, and thus not easily controllable. There will appear emerging properties and phenomena which will require monitoring and governance in an adequate way, and this will further influence the accountancy and control activities.

- A few comments on some of the above characteristics follow [16]:

- Property right on data and information: the difficulty in specifying the identification of things and humans is reflected to the difficulty to identify who is the owner of the data retrieved by IoT sensors and devices.

- Omnipresence: this makes invisible the boundaries between public and private space. People cannot know where their information ends up.

- Accessibilty of data: an attack on a PC might cause information loss. A virus or hacker attack in the IoT might have serious effects on human life (e.g., on the life of the driver of a car connected to IoT).

- Vulnerability: the list of possible vulnerabilities in IoT is scaring. It ranges from home appliances, to hospitals, traffic lights systems, food distribution networks, transportation systems, and so on.

- Digital divide: the digital divide in the IoT is enlarged. IoT operations can be understood only by experts. Communication in IoT devices affects human lives in ways that are difficult to predict or imagine. The digital divide can only be reduced by proper coherent legal and democratic frames to delineate this process.

9. IoT Ethics Questions

- What happens if the Internet connection breaks down?

- Who is responsible or liable for patching IoT devices, routers, and cloud connections?

- Is there an assurance that hacking on the cloud side of IoT services will not have access to a home’s internal network?

- What happens if an IoT service provider experiences downtime for critical life-supporting devices?

- What happens if an IoT device acts without the consent of its owner or acts in unintended ways (e.g., ordering the wrong products, or vacuuming at an unreasonable hour)?

- What happens if an IoT product vendor goes out of business and no longer supports the product?

- Who owns the data collected by IoT devices?

- Are there cases where IoT devices should not be collecting data?

- What happens if the user wants to opt out?

- What about those who do not have smart devices or the knowledge to use them? (Digital divide).

10. IoT Ethics Principles

- In IoT activities, individuals should be treated as ends (not as means), and maintain their rights to property, autonomy, private life, and dignity.

- Individuals should not suffer physical or mental harm from IoT activities.

- Benefits from the application of IoT should be added to the common good.

- The necessity and proportionality of an IoT process should be taken into account and capable of being demonstrated.

- IoT applications should be performed with maximum transparency and accountability via explicit and auditable procedures.

- There should be equal access to the benefits of IoT accruing to individuals (social justice).

- IoT activities should have minimum negative impact to all facets of the natural environment.

- IoT activities should aim to lighten the adverse consequences that data processing may have on personal privacy and other personal and social values.

- Adverse effects beyond the individual (groups, communities, societies) should be avoided or minimized or mitigated.

11. IoT Security, Privacy and Trust Issues

- Privacy regulations.

- Data minimization.

- Data portability.

- Transparency.

- Compliance disclosures.

- IoT engagement by default.

- IoT engagement by design.

- Best practice.

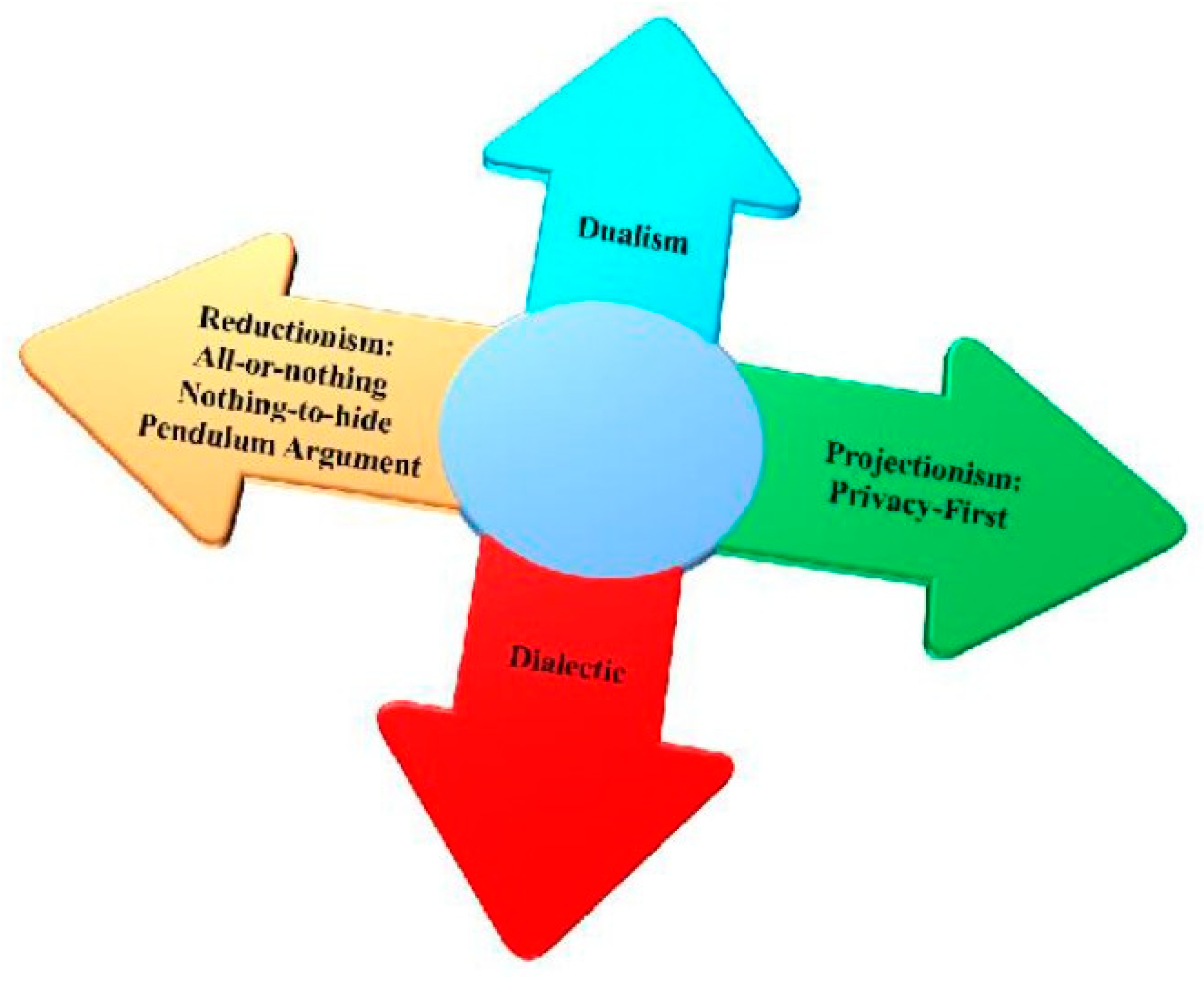

- Reductionism.

- Projectionism.

- Dualism.

- Dialectic.

- The trade-off between the market needs for data and correlation to support innovation, and the business success of the IoT systems and applications (public and private).

- The cost of verifying and implementing privacy enhancing technologies (PET) or other solutions for ensuring appropriate care in collection, storage, and retrieval of data.

- The accountability of IoT applications related to users’ privacy.

- Support for the context where the user operates.

- Trustworthiness

- Dependability

- Sustainability.

- Reliability.

- Availability.

- Resilience.

- Good reputation.

- High transparency.

- Proper education.

- People own the data (or things) they create.

- People own the data someone creates about them.

- People have the right to access data gathered from public space.

- People have the right to their data in full resolution in real time.

- People have the right to access their data in a standard format.

- People have the right to delete or backup their data.

- People have the right to use and share their data however they want.

- We believe that data generated from public space (not governed by other statutes) should be made available for use.

- We believe that customers enter relationships with vendors as independent actors, and data collected for/from/about them is available for their use, with a right action.

- Accessibility: we will publish data in an industry data format.

- Timeliness: we will release data in real-time and at full resolution.

- Privacy: we will not distribute data that contains personal identifiable information (PII) unless explicitly permitted.

- Control: we will allow the deleting and exporting of all data stored by a user.

- Licensing: users may explicitly grant legal permission for use and sharing of their data on a gradient from private to public domain.”

- Bill of Things rights.

- Bill of health data rights.

- Principles of public data.

- Principles for open government data.

- Principles for open scientific data.

12. Ethical Culture and Ethical Leadership

- Code adopted by the Internet Architecture Board (RFC 1087).

- Code of the Society of Internet Professionals (SIP).

- Code of US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (FIP: The Code of Fair Information Practices).

- The Declaration of the Internet Rights Charter of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC).

- Code of Computer Ethics Institute (The 10 commandments of computer ethics).

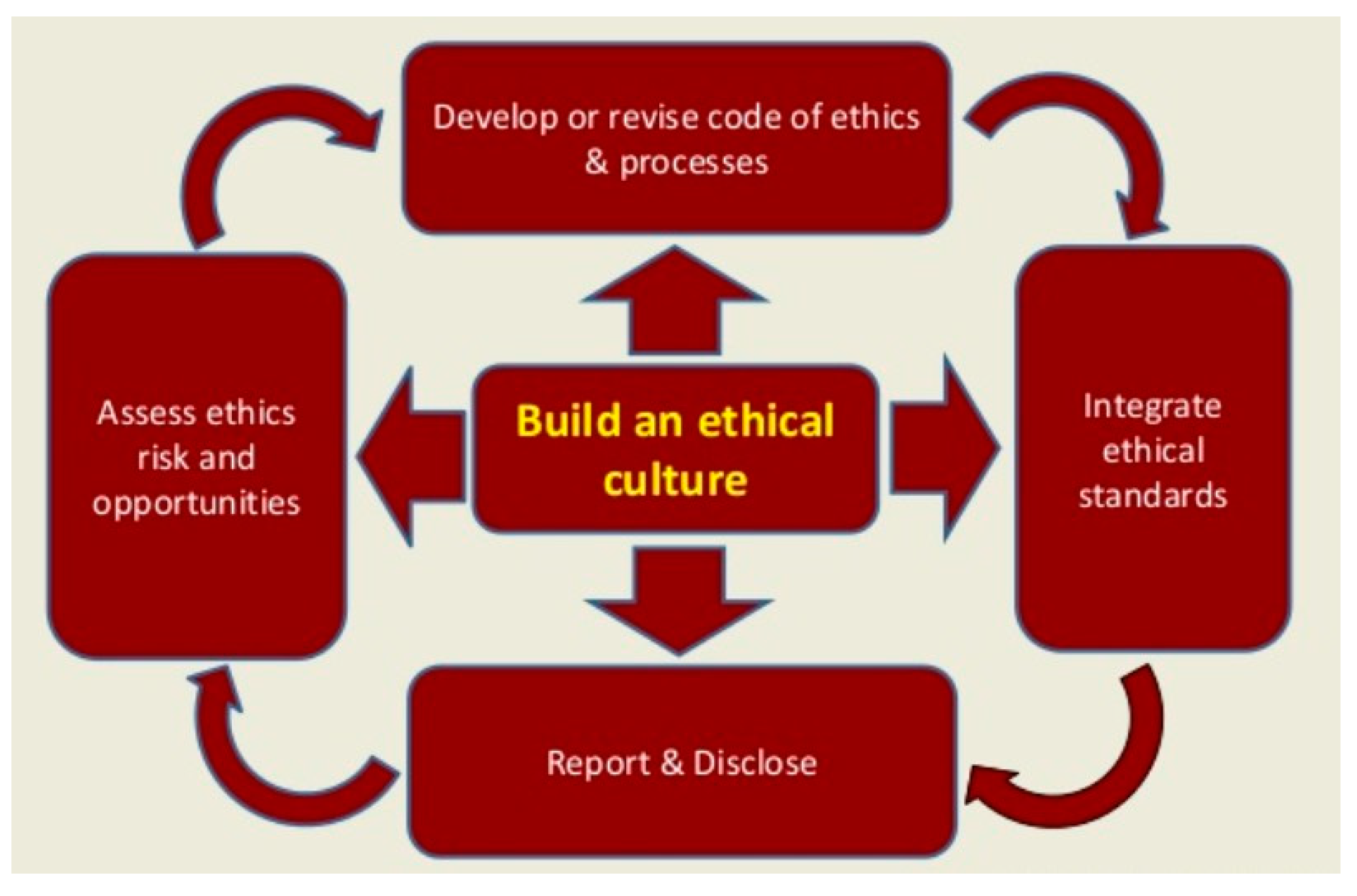

- Access ethics risk and opportunities.

- Develop or revise code of ethics and processes.

- Integrate ethical standards.

- Report and disclose.

- How well do I understand the forces and drivers that shape an ethical culture?

- Do I know how to best interfere?

- Where can I get support to answer the above questions?

- Reduces business liability.

- Helps employees make good decisions.

- Assures high-quality customer service.

- Prevents costly administrative errors and rework.

- Consistently grows the bottom line.

13. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The internet of things: A survey. Comput Netw. 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Research LLC. An Introduction to the Internet of Things (IoT). Part 1 of “The IoT Series”. November 2013. Available online: www.lopezresearch.com (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- European Parliament. The Internet of Things Opportunities and Challenges. Briefing. May 2015. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Patel, K.K.; Patel, S.M. Internet of things (IoT): Definition, characteristics, architecture, enabling technologies, application and future challenges. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Comput. 2016, 6, 6122–6131. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Tiwari, R. A review paper on “IoT” smart applications. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. Res. 2016, 5, 472–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, F. A survey on management framework and open challenges in IoT. Wireless Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, M. Wearable technologies and its future applications. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Data Commun. 2015, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Internet of Things (IoT) History. Available online: https://www.postscapes.com/internet-of-things-history (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Galipeau, D.; United Nations Social Enterprise Facility. A brief history of the IoT. In Proceedings of the APEC Philippines 2015: Workshop on IoT Development for the Promotion of Information Economy, Boracay Island, Philippines, 14 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gert, B. Morality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer-Landau, R. The Fundamentals of Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsen, A.; Tulmin, S. The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning; The University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hazard, G.C., Jr. Law, morals, and ethics. South. Ill. Univ. Law J. 1995, 19, 447–458. Available online: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/2372 (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- D’Amato, A. Obligation to Obey the Law: A Study of the Death of Socrates. S. Cal. L. Rev. 1975, 49, 1079. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, G.; Botterman, M.; Neisse, R.; Tallacchini, M. Ethical design in the internet of things. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2016, 24, 905–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescul, D.; Georgescu, M. Internet of things: Some ethical issues. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2013, 13, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rehiman, R.; Veni, S. Security, privacy, and trust for smart mobile devices in the internet of things: A literature study. Int. J. Adapt. Res. Comput. Eng. Technol. 2015, 4, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar]

- AboBakr, A.; Azer, M. IoT ethics challenges and legal issues. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 19–20 December 2017; pp. 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- What is the role of government in the digital age? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/2017/02/role-of-government-digital-age-data/ (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- BBVA Research Digital Economy Outlook—3. The Internet of Things: European Regulation. Available online: https://www.bbvaresearch.com/the_internet_of_things_european_regulation_DEO_Jul16-Cap3.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Gemalto Com. The State of IoT Security: Government Regulations and Impact. Available online: https://www2.gemalto.com/iot/iot-regulations.html (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Eisenhart, S. European Internet of Things Cybersecurity Recommendations: IMPACT for Medical Devices (ENISA Recommendations). Available online: https://www.emergobyul.com/blog/2017/12/european-internet-of-things-cybersecurity-recommendations-impact-medical-devices (accessed on 18 December 2017.).

- European Commission. Proposal for General Data Protection Regulation; COM 11/4 Draft; European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies, European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EUR-Lex Document 32013L0040. Directive 2013/40/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 12 August 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013L0040 (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- NIS Directive. The Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/network-and-information-security-nis-directive (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- EUR-Lex Document 32014L0053. Directive 2014/53/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 16 April 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014L0053 (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- EUR-Lex Document 32016R0679. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679 (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- EU Connected Communities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/events/cf/connected-communities-experience-sharing/item-display.cfm?id=15644 (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Europe 2020 “Innovation Europe”. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/innovation-union/index_en.cfm?pg=home (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- IERC: Internet of Things Research. Available online: www.internet-of-things-research.eu/about_ierc.htm. (accessed on 11 October 2018).

- UNIFY-IoT. Available online: www.unify-iot.eu (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Fair Housing Act. 1968. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-2 (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Fair Credit Reporting Act. 2012. Available online: http://www.consumer.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/articles/pdf/pdf-0111-fair-credit-reporting-act.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Equal Employment Opportunity Act. 1972. Available online: https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/history/35th/thelaw/eeo_1972.htm (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Electronic Communications Privacy Act. 1986. Available online: https://it.ojp.gov/PrivacyLiberty/authorities/statutes/1285 (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Fair Information Practice Principles. Available online: http://itlaw.wikia.com/wiki/Fair_Information_Practice_Principles (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Breach Notification Rule (2009). Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/breach-notification/index.htm (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- White House. Consumer Data Privacy in a Networked World: A Framework for Protecting Privacy and Promoting Innovation in the Global Digital Economy. 2012. Available online: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/privacy-final.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2017. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/355269230/Internet-of-Things-Cybersecurity-Improvement-Act-of-2017 (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Kallis, P. The US “Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2017” as an Example for EU Regulation? Available online: www.leidenlawblog.nl/activities/the-u.s.-internet-of-things-cybersecurity-improvement-act-of-2017 (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Van den Hoven, J. Internet of Things. Factsheet-Ethics Subgroup IoT-Version 4.01. 2012. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/news/conclusions-internet-things-public-consultation (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Clubb, K.; Kirch, L.; Patwa, N. The Ethics, Privacy, and Legal Issues around the Internet of Things, W231. 2015. Available online: https://www.ischool.berkeley.edu (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Raab, C.; Stewart, J.; Dominguez, A.; Klein, E.; Chapple, S. University of Edinburgh IoT Initiative Principles v1.1c. Available online: www.iot.ed.ac.uk (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- UNIFY-IoT PROJECT: Policy Recommendation of the Uptake of IoT in the European Region, Deliverable 02.03. Available online: www.unify-iot.eu (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Nissenbaum, H. Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2015, 24, 831–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open Internet of Things Assembly. London. 2012. Available online: https://www.postscapes.com (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Chadwick, R. Professional ethics. In Routlege Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Craig, E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, A. Ethical Leadership: Creating and Sustaining an Ethical Business Culture; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Starrat, R.J. Ethical Leadership; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- PlantServicesCom. Available online: https://www.plantservices.com/industrynews/2017/forbes-releases-iot-forecasts-for-2018-notes-84-growth-of-network-connections-in-manufacturing (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Simoens, R.; Dragone, M.; Saffioti, A. The internet of robotic things: A review of concept, added value and applications. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevold, H.P.; Sandstrom, K. Internet of things for industrial automation: Challenges and solutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Data Science Technical Solutions and Data Intensive Systems, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 11–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tzafestas, S.G. Roboethics: Fundamental concepts and future prospects. Information 2018, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafestas, S.G. Ethics in robotics and automation: A general view. Int. Robot. Autom. J. 2018, 4, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiekerman, S. About the ‘idea of man’ in system design: An enlightened version of the internet of things. In Architecting the Internet of Things; Uckelman, D., Harrison, M., Michahelles, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.L.; Reilly, K.M.A. Open Development: Networked Innovations in International Development; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; IDRC: Ottawa, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nadhan, E.G. The Real Dilemma of Ethics and IoT. Available online: https://www.experfy.com/blog/the-real-dilemma-of-ethics-and-iot (accessed on 11 October 2018).

| Law | Ethics |

|---|---|

| Written formal document | Non-written principles and rules |

| Created by judicial systems | Presented by philosophers and professional societies |

| Compulsory for everyone | Personal choice (according to conscience and ethics education) |

| Interpreted by courts | Interpreted by each person |

| Priority decided by court | Priority determined by individual |

| Enforceable by police and courts | Not enforced but applied at will or suggested by professional societies |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tzafestas, S.G. Ethics and Law in the Internet of Things World. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 98-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities1010006

Tzafestas SG. Ethics and Law in the Internet of Things World. Smart Cities. 2018; 1(1):98-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities1010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTzafestas, Spyros G. 2018. "Ethics and Law in the Internet of Things World" Smart Cities 1, no. 1: 98-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities1010006

APA StyleTzafestas, S. G. (2018). Ethics and Law in the Internet of Things World. Smart Cities, 1(1), 98-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities1010006